Introduction

More than 200 000 children are diagnosed with cancer each year worldwide.

A total of 80% are diagnosed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1

There is a substantial survival gap between patients with cancer in high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs, such as Mexico, where 5-year overall survival(OS) rates are 5% to 35% compared with 80% to 85% in HICs.

Cancer, particularly leukemia, is the leading cause of death in children 5 to 14 years of age in Mexico2,3 and the 3-year OS rate for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is low at 50%.4

The Mexican State of Baja California shares a 145-mile border with the state of California and has a population of 3.3 million.5

A total of 40% are <18 years old.

Survival rates for pediatric leukemia in Mexico are very poor. Reasons for poor outcomes in Baja California include:

high poverty rates,

high malnutrition rates,

long distances to hospitals and limited transportation,

high rates of family violence, and

a large floating immigrant population.

In Mexico, before 2008, a pediatric oncology unit did not exist in Baja California and most children went untreated.6

In 2008, leaders at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital established a “twinning” partnership with the Hospital General de Tijuana (GHT), the largest public hospital in northwestern Mexico to improve access to care and improve survival in pediatric cancer patients.

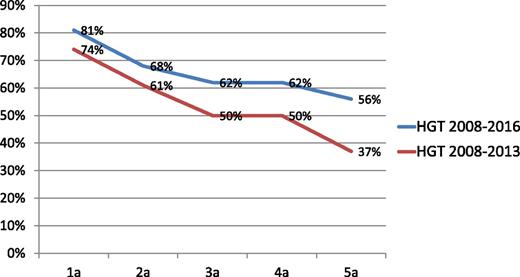

Five-year event-free survival for pediatric ALL increased from 37% to 56%.

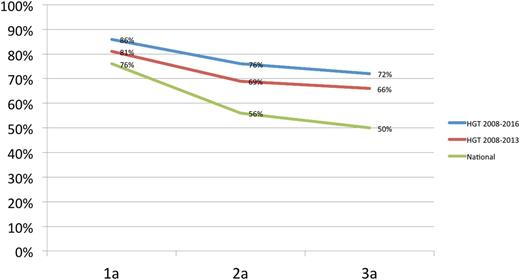

Three-year overall survival for pediatric ALL is 70% at the GHT compared with 50% reported in Mexico.

Three-year overall survival for pediatric ALL is 70% at the GHT compared with 50% reported in Mexico.

Objectives

To establish a multilevel capacity-building initiative based on the health systems strengthening principles7 aimed at providing adequate access to care for pediatric patients with ALL at the GHT.

To assess the effectiveness of the multilevel capacity-building initiative in improving the outcomes for pediatric patients with ALL at the GHT, particularly, 3-year and 5-year overall and event-free survival rates.

Methods

We followed implementation principles to establish the multilevel initiative.

In 2008, we conducted an initial needs assessment and developed an action plan following Swanson’s health systems strengthening principles. The needs assessment findings included:

Holism: One takes a holistic approach when one considers all systems components, processes, and relationships simultaneously.

Access to adequate care was fragmented and suboptimal.

Health care system components, local processes, and relationships were not established.

Context and collaboration: One considers the context when one considers global, national, regional, and local culture and politics. Collaboration takes place when long-term and equal relationships are fostered in all sectors and organizations involved.

There was no collaboration either within the hospital or with a center in a HIC.

Social mobilization: Social mobilization refers to efforts that advocate for social and political change to improve health systems and social determinants of health.

There was no awareness regarding pediatric cancer in the community and grassroots efforts were very limited.

Capacity enhancement: This occurs when individuals, communities, ministries of health, and other stakeholders in the health system become better able to provide for the various levels of health care and accept ownership for doing so.

Infrastructure was very basic, there was no isolated unit for pediatric cancer patients.

There was no multidisciplinary team.

Staff lacked training in pediatric leukemia care.

There were no pediatric protocols for the treatment of patients with ALL or supportive care guidelines.

Patients and families lacked psychological support, financial assistance, education in patient care, and a shelter.

Equity: One strengthens health systems in an equitable way when one focuses on and empowers those who are marginalized.

We found profound disparities for children with cancer in the border region in access to care and clinical outcomes.

Evidence-informed action: This is when systems and processes are put in place to gather, analyze, and apply local data, make decisions based on evidence, monitor programs, and strive for transparency.

The hospital lacked a database, a hospital-based cancer registry, and programmatic projects to improve care.

Financial protection: Predictable funding streams dramatically affect the way an organization is able to operate and plan.

There was no grass-roots foundation to support the program and government support was limited.

The Multilevel Capacity-Building Plan was implemented to:

Ensure long-term programmatic and financial sustainability,

Form and train a multidisciplinary team, and

Implement projects to improve patient care and optimize clinical outcomes for pediatric ALL.

Results

Holism:

We took a holistic approach at the GHT by involving all stakeholders and implementing a multilevel initiative to improve patient care.

Context and collaboration:

We established a long-term partnership among teams at the GHT, Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, St. Jude Children’s Hospital, the state government in Baja California, and a local foundation in Tijuana, Patronato. This has been crucial to the success of the multilevel initiative.

Social mobilization:

The local foundation, Patronato, has played a major role as the main advocate of the children, impacting the local community and society. This led to a successful implementation of the new multilevel capacity-building initiative.

Capacity enhancement:

Capacity-building enhancement has taken place at all levels with the establishment of:

an independently-operated pediatric cancer unit,

a targeted training program for the staff and the patients and their families,

a multidisciplinary cohesive team with 62 members (pediatric oncologists, infection disease specialists, intensive care specialists, pediatricians, oncology nurses, psychologists, social workers, surgeons, dietitians, dentists, pharmacists, and data managers),

an early detection program to refer patients promptly to the GHT.

Equity:

Clinical outcomes have improved dramatically for ALL in the US-Mexico border area. There was a total of 331 new cancer cases at the GHT from 2008 to 2016, and 32% (n = 105) were diagnosed with ALL.

Evidence-informed action:

The team at the GHT has implemented several evidence-informed quality improvement projects, including:

a new data management system that allows for analyses of data and helps with decision-making activities, and

treatment protocols and supportive therapy guidelines.

Specific for ALL:

infection prevention and risk-specific therapy to decrease mortality, and

adherence to therapy.

Conclusions

The multilevel capacity-building initiative based on Swanson’s health systems strengthening principles has been successful in improving clinical outcomes for patients with pediatric ALL at the GHT, particularly survival.

This approach has led to superior outcomes, particularly a 3-year survival rate of 72% at the GHT compared with 50% for the rest of Mexico.4

This capacity-building initiative has mitigated disparities across the US-Mexico border, and a similar approach could be implemented in other LMICs. Future directions include regional initiatives to improve care at a larger scale.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the patients and families at Hospital General de Tijuana and the teams at the Hospital General de Tijuana, Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Parental permission for use of photographs of children was obtained.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure:

P.A.: American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Clinician-Educator Award (research funding), NIH/CTSA (research funding, other), American Society of Hematology Scholar Award (research funding, other), Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation Psychosocial Grant (research funding). Other authors: no competing financial interests declared.

Correspondence: Laura Nuño-Vázquez, Hospital General de Tijuana, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; e-mail: hematologanuno@gmail.com; and Paula Aristizabal, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA; e-mail: paristizabal@rchsd.org.