Key Points

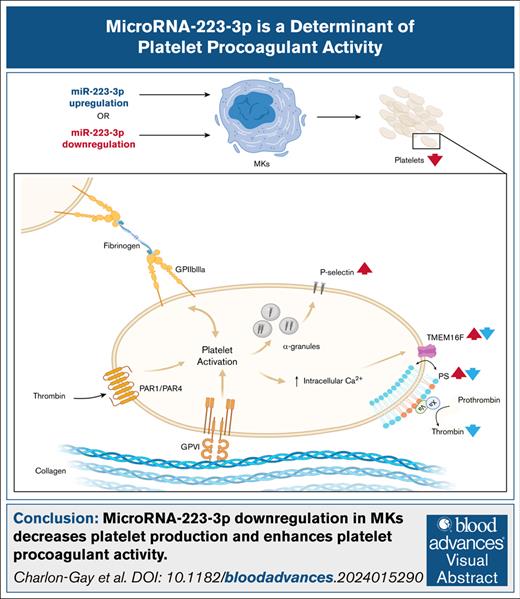

miRNA-223-3p downregulation in MKs decreases platelet production and enhances platelet procoagulant activity.

TMEM16F messenger RNA is a target of miR-223-3p.

Visual Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are regulators of platelet function and may, thus, contribute to interindividual variability in platelet reactivity. MicroRNA-223-3p (miR-223-3p) is the most abundant of the platelet-derived miRNAs. Several studies have reported an association between miR-223-3p levels and platelet reactivity or the recurrence of cardiovascular events; however, the impact of this miRNA on platelet function remains poorly understood. This study aimed to investigate the effects of miR-223-3p on platelet reactivity in platelets derived from human hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+), and to study the underlying mechanisms of its action. miR-223-3p upregulation and downregulation were performed by transfecting megakaryocytes (MKs) derived from CD34+ cells with a miR-223-3p mimic or Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes, respectively. Flow cytometry was used to quantify the expression of surface markers of MKs and platelets, platelet production, and platelet reactivity. Platelet-supported thrombin generation was quantified in human plasma. Downregulation of miR-223-3p resulted in fewer proplatelet swellings and decreased platelet production. miR-223-3p upregulation and downregulation affected the proportion of procoagulant platelets. This phenotype was mirrored by changes in the gene expression of the transmembrane protein 16F (TMEM16F), a phospholipid scramblase that plays a key role in the generation of procoagulant platelets. A luciferase reporter gene assay validated that TMEM16F messenger RNA was a direct target of miR-223-3p. Platelet-supported thrombin generation was reduced when miR-223-3p was upregulated. In conclusion, miR-223-3p modulates the generation of procoagulant platelets.

Introduction

Platelets are anucleate blood cell fragments derived from megakaryocytes (MKs); they play a crucial role in hemostasis. Upon vascular injury, platelets adhere to the subendothelial matrix, initiating their activation and subsequent aggregation, resulting in the formation of a platelet plug. Simultaneously, a subpopulation of platelets, called procoagulant platelets, exposes phosphatidylserine on their surfaces, promoting the generation of bursts of thrombin and fibrin required to form a stable thrombus.1

Platelets contain a diverse transcriptome, including >750 microRNAs (miRNAs).2 They contain the necessary machinery to process these miRNAs (such as the Dicer/Transactivation Response Binding Protein 2 [TRBP2] complex and Argonaute 23,4) and thus regulate protein production. Of note, circulating miRNAs are believed to originate primarily from platelets and may reflect the status of platelet function. This is best illustrated by the different profiles of circulating miRNA in control subjects and patients undergoing antiplatelet therapies.5

MicroRNA-223-3p (miR-223-3p) is the most highly expressed miRNA in platelets and MKs6 and has been found to be preferentially released in microparticles after platelet activation.7 Several studies have reported a negative correlation between levels of circulating miR-223-3p and platelet reactivity,8 response to antiplatelet therapy,5 or recurrence of ischemic events in cardiovascular patients.6,8 However, the mechanisms involved in the miR-223–mediated regulation of platelet function are still poorly understood. This study aimed, therefore, to investigate the role of miR-223-3p in regulating platelet reactivity.

Methods

Generation of platelets derived from cultured human hematopoietic stem cells

Human hematopoietic stem (CD34+) cells were isolated from the buffy coats of healthy adult human donors and cultured for 7 days before inducing their differentiation into MKs. Details can be found in the supplemental Materials.

miR-223-3p upregulation

On day 12, MKs were resuspended at 5 × 105 cells per mL in StemSpan serum-free expansion medium.

MKs were transfected using lipofection on day 13 of culture. A control miRNA (catalog no. 4464059; Thermo Fisher), which targets no specific messenger RNA (mRNA), was used as a negative control. Lipofection complexes were formed by mixing INTERFERin (catalog no. 101000028; Polyplus, Illkirch, France), Opti-MEM (catalog no. 11058-021; Gibco), and 100 nM hsa-miR-223-3p mimic (catalog no. 4464067; Thermo Fisher) or 100 nM control miRNA for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT). The lipofection complexes were then dropped onto the cells, and platelets were recovered on day 15 for platelet reactivity characterization. Details on the lipofection procedure efficiency can be found in the supplemental Materials.

miR-223-3p downregulation

On day 6, cells were resuspended at 7.5 × 104 cells per mL in StemSpan serum-free expansion medium, supplemented with low-density lipoprotein and StemRegenin 1 (SR1).

CD34+ cells were transfected using nucleofection (catalog no. AAF-1003X; 4D-Nucleofector X Unit; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes on day 7 of culture using a P3 primary cell 4D-Nucleofector X kit (catalog no. V4XP-3032, Lonza). The sequences of the sgRNAs used were sg4 (CUUGUCAAAUACACGGAGCG) and sg9 (UUUGUCAAAUACCCCAAGUG; supplemental Figure 1). A nontargeting sgRNA (catalog no. 2; Synthego, Redwood City, CA) was used as a negative control. In brief, Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes were formed by mixing P3 primary cell solution, sgRNAs (3.6 μM final for each sgRNA) or a negative control (3.6 μM), and Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 2NLS Nuclease (1 μM; Synthego) for 10 minutes at RT. Cells were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 200g and washed once using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, 25 μL of the Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes were added to the cell pellet. Cells were nucleofected using Lonza nucleofector program EO-100 and seeded at 5 × 104 cells per mL in a 24-well plate with 1 mL of prewarmed media (StemSpan) supplemented with low-density lipoprotein, SR1, and 0.5 μg/mL of Thrombopoietin (TPO). Platelet reactivity assays were performed on day 14. Details on the nucleofection procedure efficiency, the detection of potential CRISPR/Cas9 off-target mutations, followed with DNA extraction and Sanger sequencing analysis can be found in the supplemental Materials.

RNA extraction and quantification

Details on mRNA and miRNA extraction and quantification can be found in the supplemental Materials.

Assessment of MK differentiation

Platelets and MKs were centrifuged in brake-off mode at 200g for 10 minutes at 37°C. The supernatant containing platelets was discarded, and MKs were resuspended at 1.3 × 106 cells per mL in PBS. MKs were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/mL; catalog no. H1399; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) for 10 minutes at 37°C and labeled with anti–CD34-phycoerythrin (PE) (catalog no. 130-113-179; Miltenyi Biotec), anti–CD41-FITC (catalog no. 303704; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), anti–CD42b-allophycocyanin (APC) (catalog no. 303912; BioLegend), and primary anti-CD42d (catalog no. MAB4249; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) followed by secondary PerCp/Cy5.5 rat anti-mouse antibody (catalog no. 405314; BioLegend) for 20 minutes at RT. Flow cytometry was performed on a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.8.0 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Assessment of proplatelet formation

After transfection, MKs were seeded at 5000 cells per well in a 96-well plate (catalog no. 655892; Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria). On assay day, images were captured at ×20 magnification (20× CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda, 0.75 numerical aperture [NA], 1 mm working distance [WD]) using an ImageXpress Micro confocal high-content imaging system (Molecular Devices, San José, CA) and analyzed using QuPath software version 0.5.1. Proplatelet-forming MKs were defined as MKs with at least 1 pseudopodium. The proportion of proplatelet-forming MKs was defined as the number of MKs with proplatelets divided by the total number of MKs. At least 500 MKs were analyzed per condition. The pseudopodia areas and the number of proplatelet swellings were also quantified for at least 50 proplatelet-forming MKs per condition.

Quantification of platelet production

where Vbeads is precision count bead volume, Cbeads is precision count bead concentration, and Vplatelets is platelet suspension volume.

Platelet glycoprotein expression

Platelets were resuspended at 1.3 × 106 cells per mL in filtered PBS and labeled with anti–CD61-APC (catalog no; 130-110-750; Miltenyi Biotec), anti–CD49b-FITC (catalog no. 555498; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), anti–glycoprotein VI - phycoerythrin (GPVI-PE) (catalog no. 565241; BD Biosciences), anti–CD42a-BV421 (catalog no. 565444; BD Biosciences), anti–CD42b-APC, and primary anti-CD42d, followed by secondary PerCp/Cy5.5 rat anti-mouse antibody for 20 minutes at RT. Platelets were identified using anti–CD41-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or anti–CD41-V450 (catalog no. 561425; Becton Dickinson [BD] Biosciences), depending on the combination of antibodies. Appropriate isotype antibodies were used to set up cutoff values. Platelets were washed using PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 4°C, and washed a second time. Flow cytometry and analysis were performed, as described previously.

Platelet reactivity evaluation

Platelets were resuspended at 106 cells per mL in Tyrode’s albumin buffer and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour before reactivity assessment.9

Phosphatidylserine exposure

Phosphatidylserine exposure was induced by the addition of thrombin (5 U/mL, 176 National Institutes of Health U/mg; catalog no. PRO-447; ProSpec, Rehovot, Israel) and convulxin (0.5 μg/mL; catalog no. AG-CN2-0465-C050; Adipogen, Epalinges, Switzerland), as recommended by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis’ Scientific and Standardization Committee,10 for 8 minutes at 37°C in the presence of annexin binding buffer 1× (catalog no. V13246; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). They were then labeled with anti–CD41-FITC, anti–CD62P-PE antibodies (catalog no. 555524; Becton Dickinson Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and annexin V Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (catalog no. A23204; Invitrogen). Calcium ionophore A23187 (2 μM; catalog no. C7522; Sigma-Aldrich) and EGTA-AM (1 mM; catalog no. E1219; Invitrogen) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

P-selectin expression and GPIIb/IIIa activation

P-selectin expression and GPIIb/IIIa activation were induced by adding thrombin (1 U/mL) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Platelets were labeled with anti–CD31-APC (catalog no. 303116; BioLegend) and anti–CD62P-PE or anti–PAC-1-FITC antibodies (catalog no. 340507; BD Biosciences). Anti–PAC-1 specifically recognizes the active conformation of GPIIb/IIIa.

Appropriate isotypic antibodies were used to set up cutoff values. Flow cytometry and analysis were performed as described previously.

Calcium flux

Platelets were resuspended at 2.5 × 106 cells per mL and labeled with anti–CD41-PE, Hoechst, and Fluo-3-AM (2 μM; catalog no. F1241; Invitrogen) for 15 minutes at 37°C. The calcium flux baseline was measured for 2 minutes. Platelets were activated using thrombin (5 U/mL) and convulxin (0.5 μg/mL), and acquisition was resumed for up to 10 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.8.0.

Thrombin generation assay

A calibrated automated thrombogram (CAT) assay (Stago, Asnière-sur-Seine, France) was used to evaluate the thrombin generation potential of MKs and platelets. Cells were resuspended at 3.125 × 106 cells per mL in human plasma (catalog no. CCN-10; Cryocheck pooled normal plasma; Precision BioLogic, Dartmouth, Canada) and incubated for 1 hour before the assay. Thrombin generation was triggered by adding platelet-rich plasma reagent (catalog no. 86196; Stago) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with or without previous stimulation using thrombin receptor activator peptide (TRAP) (15 μM; catalog no. 4017752; Bachem Holding, Bubendorf, Switzerland) and Horm collagen type I (20 μg/mL; catalog no. 1130630; Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Samples were run in triplicates. Thrombin generation potential was evaluated via the velocity index (a parameter that recapitulates the lag time, the thrombin peak, and the time to peak parameters), and the endogenous thrombin potential was calculated using Thrombinoscope software version 5.0 (Stago).

Plasmids and reporter gene assay

Details on plasmid generation and the reporter gene assay can be found in the supplemental Materials.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Paired Student t tests, 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance were performed, followed by Sidak multiple comparison test, when appropriate. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Modulation of miR-223-3p levels in platelets derived from cultured human hematopoietic stem cells

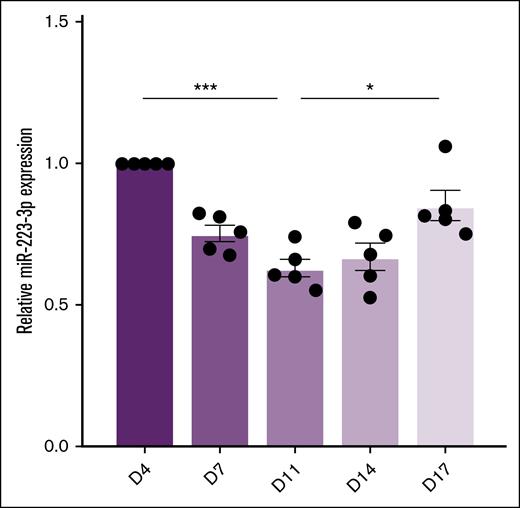

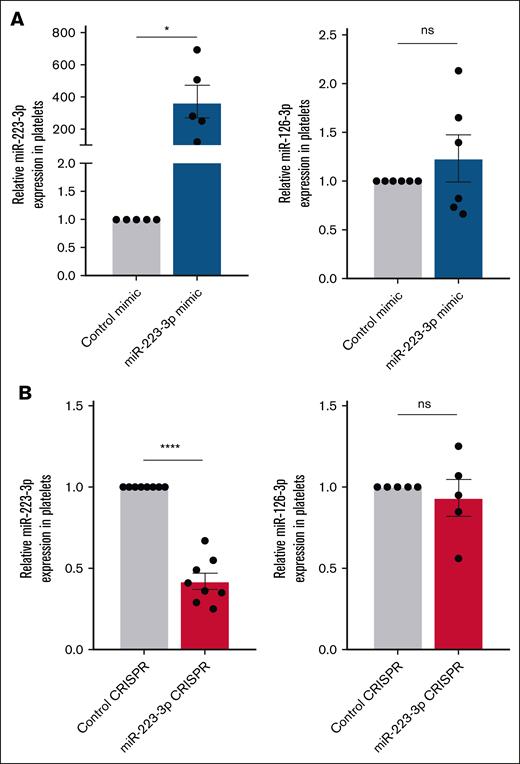

The quantification of miR-223-3p levels during standard human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation (days 4-17) revealed a U-shaped profile (Figure 1), with significantly reduced levels between days 4 and 11, followed by an increase between days 11 and 17. Lipofection of MKs with the miR-223-3p mimic on day 13 led to a 371-fold increase in miR-223-3p expression in platelets (Figure 2A left) compared with the control. Lipofection efficiency was 43% ± 9%, similar to our previous study.11 Conversely, nucleofection of MK progenitors with Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes on day 7, targeting the miR-223-3p sequence, led to a 58% ± 5% lower miR-223-3p expression in platelets (Figure 2B left) compared with the control. Nucleofection efficiency, defined as the proportion of green fluorescent protein–positive cells after transfection with the pmaxGFP vector, was 43% ± 5%. Sanger sequencing analysis of potential off-target mutations revealed no CRISPR-mediated indels compared with the control samples. To further validate the specificity of our 2 approaches, we quantified the expression of miR-126-3p, an abundant platelet miRNA. Modulating levels of miR-223-3p had no detectable effect on miR-126-3p concentrations in platelets (Figure 2A-B right).

miR-223-3p expression levels during human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Results are expressed relative to the values on day 4. n = 5 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001.

miR-223-3p expression levels during human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Results are expressed relative to the values on day 4. n = 5 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Modulation of miR-223-3p levels in platelets. (A) Levels of miR-223-3p (left) and miR-126-3p (right) expression in platelets 48 hours after MK transfection with a miR-223-3p mimic or a negative control. (B) Levels of miR-223-3p (left) and miR-126-3p (right) expression in platelets 7 days after MK progenitor nucleofection with CRISPR-Cas9 complexes or a negative control. Data are from 5 to 8 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, non-significant.

Modulation of miR-223-3p levels in platelets. (A) Levels of miR-223-3p (left) and miR-126-3p (right) expression in platelets 48 hours after MK transfection with a miR-223-3p mimic or a negative control. (B) Levels of miR-223-3p (left) and miR-126-3p (right) expression in platelets 7 days after MK progenitor nucleofection with CRISPR-Cas9 complexes or a negative control. Data are from 5 to 8 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, non-significant.

Impact of miR-223-3p on megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis

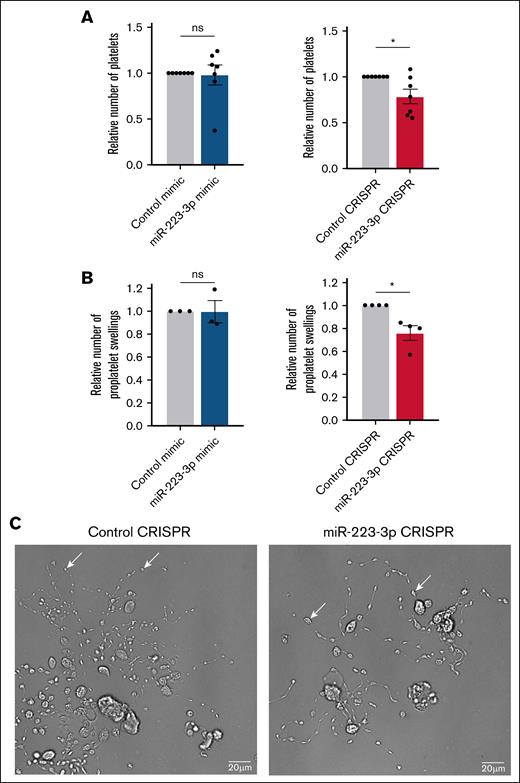

The impact of miR-223-3p on megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis was studied by evaluating MK ploidy, the expression of differentiation markers CD41 (GPIIb), CD42b (GPIbα), and CD42d (GPV); the quantification of platelet production; and the expression of the main platelet glycoproteins, including CD41, CD61 (GPIIIa), CD42a (GPIX), CD42b, CD42d, CD49b (GPIa), and GPVI. MKs were identified as Hoechst-positive/CD41+ cells, and platelets were identified as Hoechst-negative/CD41+ cells in all flow cytometry analyses. The evaluation of MK ploidy (supplemental Figure 2A-B), the expression of MK differentiation markers (supplemental Figure 2C), and the expression of the main platelet glycoproteins (supplemental Figure 3) revealed no differences when miR-223-3p was upregulated or downregulated. The average number of platelets produced in the control condition was 6.8 × 105 ± 2.5 × 105 platelets per mL (starting with 5 × 104 MK progenitors per mL on day 7). Although no differences in platelet production were observed when miR-223-3p was upregulated (Figure 3A left), miR-223-3p downregulation induced a 21% ± 8% decrease (Figure 3A right). Microscopic analysis of proplatelet formation revealed that the total area of cytoplasmic extensions, representing the proplatelet network area (1.5 × 103 ± 0.5 × 103 μm2 in the control condition), remained unchanged after miR-223-3p modulation (supplemental Figure 4). However, a 24% ± 6% decrease in the number of proplatelet swellings along these extensions was observed when miR-223-3p was downregulated (Figure 3B). As illustrated in Figure 3C, when the cellular concentration of miR-223-3p decreased, the cytoplasmic extensions contained fewer proplatelet swellings, with noticeable gaps between them, compared with the negative control. An average of 33 ± 3 proplatelet swellings per proplatelet network was measured in the control condition. These results were associated with a 54% ± 22% increase in MK Stathmin1 (STMN1) mRNA expression (supplemental Figure 5), a validated target of miR-223-3p.12 The STMN1 gene codes for a protein with an important role in the regulation of MK cytoskeleton13,14 and platelet production.15

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on thrombopoiesis. Relative number of platelets in the cell culture (A) and proplatelet swellings per MK (B), after miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right), compared with the negative control. (C) Representative bright-field microscopy images (ImageXpress micro confocal high-content imaging system microscope, ×20 original magnification; scale bar, 20 μm) of human MKs forming proplatelet network derived from CD34+ cells in negative control (left) and miR-223-3p downregulation (right) conditions. White arrows show proplatelet swellings. Data are from 3 to 7 independent experiments. ∗P < .05. ns, non-significant.

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on thrombopoiesis. Relative number of platelets in the cell culture (A) and proplatelet swellings per MK (B), after miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right), compared with the negative control. (C) Representative bright-field microscopy images (ImageXpress micro confocal high-content imaging system microscope, ×20 original magnification; scale bar, 20 μm) of human MKs forming proplatelet network derived from CD34+ cells in negative control (left) and miR-223-3p downregulation (right) conditions. White arrows show proplatelet swellings. Data are from 3 to 7 independent experiments. ∗P < .05. ns, non-significant.

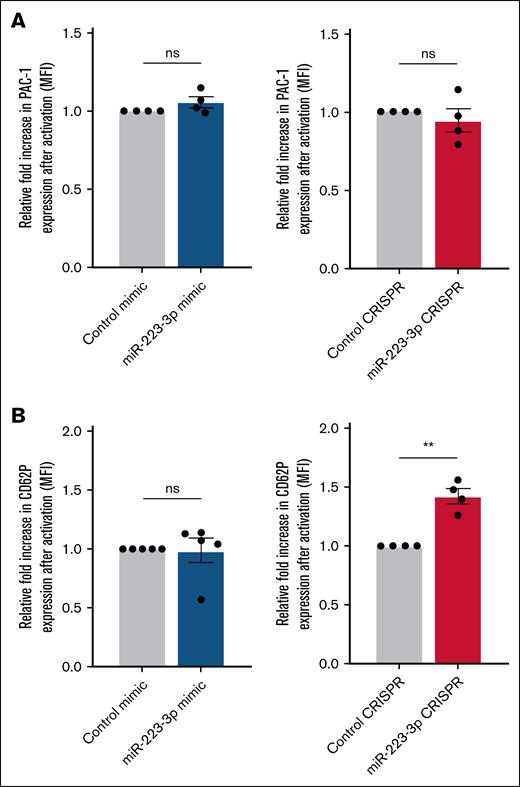

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on GPIIb/IIIa activation and P-selectin expression

GPIIb/IIIa activation and P-selectin expression were evaluated by quantifying PAC-1 and CD62P mean fluorescence intensity at the cell surface, respectively. Upregulation of miR-223-3p did not influence GPIIb/IIIa activation or P-selectin expression, either before or after stimulation with thrombin (Figure 4A-B left). Interestingly, the downregulation of miR-223-3p had no impact on GPIIb/IIIa activation (Figure 4A right), but it did induce a 31% ± 5% increase in P-selectin expression after stimulation (Figure 4B right).

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on GPIIb/IIIa activation and P-selectin expression. Relative fold increase in mean fluorescence of PAC-1 (A) and CD62P (B) after thrombin activation, under conditions of miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right). Data are from 4 to 5 independent experiments. ∗∗P < .01. MFI, mean florescence intensity; ns, non-significant.

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on GPIIb/IIIa activation and P-selectin expression. Relative fold increase in mean fluorescence of PAC-1 (A) and CD62P (B) after thrombin activation, under conditions of miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right). Data are from 4 to 5 independent experiments. ∗∗P < .01. MFI, mean florescence intensity; ns, non-significant.

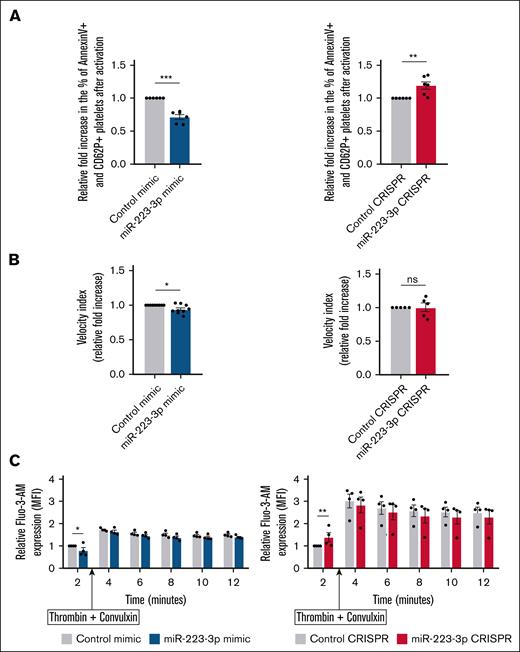

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on platelet procoagulant activity

To determine the impact of miR-223-3p on platelet procoagulant activity, we quantified the proportion of procoagulant platelets, defined as annexin V–positive/CD62P+ cells.10 Before stimulation, the proportion of procoagulant platelets was very similar in both groups (7% ± 1% vs 6% ± 1% in upregulation condition vs control; and 5% ± 0.5% vs 6% ± 1% in downregulation condition vs control; P = non-significant [ns]). miR-223-3p upregulation induced a 32% ± 7% decrease (Figure 5A left) in the fold change of the proportion of procoagulant platelets upon stimulation, whereas its downregulation led to a 19% ± 6% increase (Figure 5A right). When platelets and MKs were resuspended in human plasma, thrombin generation, as measured with the velocity index, averaged 7.5 ± 0.9 nM/min before stimulation and 9.4 ± 1.1 nM/min after stimulation in the control condition. Increased levels of miR-223-3p induced a 10% ± 3% decrease in the velocity index (Figure 5B left), without affecting the endogenous thrombin potential (data not shown). There was no significant difference when miR-223-3p was downregulated (Figure 5B right). Because calcium flux is a critical event in the generation of procoagulant platelets,16,17 we investigated the impact of miR-223-3p modulation on calcium levels at baseline and after stimulation. Before platelet stimulation, we observed a 20% ± 5% reduction of Fluo-3-AM mean fluorescence intensity when miR-223-3p was upregulated (Figure 5C left; T = 2 minutes) and a 40% ± 8% increase was observed when miR-223-3p was downregulated (Figure 5C right; T = 2 minutes). No significant difference in calcium flux was observed after stimulation with thrombin and convulxin at any other time points studied (Figure 5C). Thus, it was hypothesized that, after platelet activation, the difference in the proportion of procoagulant platelets related to miR-223-3p levels might be due to a mechanism downstream from the regulation of calcium flux. Because the transmembrane protein 16F (TMEM16F) scramblase plays a major role in phosphatidylserine exposure,18 we examined whether this transcript could be regulated by miR-223-3p.

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on platelet procoagulant activity. (A) Relative fold increase in the proportion of procoagulant platelets after activation with thrombin and convulxin. (B) Quantification of platelet-supported thrombin generation (velocity index parameter) after activation with TRAP and collagen. miR-223-3p upregulation relative to the negative control (left); miR-223-3p downregulation relative to the negative control (right). (C) Calcium flux (Fluo-3-AM MFI) quantification over time, before and after activation with thrombin and convulxin. Data are from 4 to 9 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Fluo-3-AM, fluo-3-pentaacetoxymethyl ester; MFI, mean florescence intensity; ns, non-significant.

Impact of miR-223-3p modulation on platelet procoagulant activity. (A) Relative fold increase in the proportion of procoagulant platelets after activation with thrombin and convulxin. (B) Quantification of platelet-supported thrombin generation (velocity index parameter) after activation with TRAP and collagen. miR-223-3p upregulation relative to the negative control (left); miR-223-3p downregulation relative to the negative control (right). (C) Calcium flux (Fluo-3-AM MFI) quantification over time, before and after activation with thrombin and convulxin. Data are from 4 to 9 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Fluo-3-AM, fluo-3-pentaacetoxymethyl ester; MFI, mean florescence intensity; ns, non-significant.

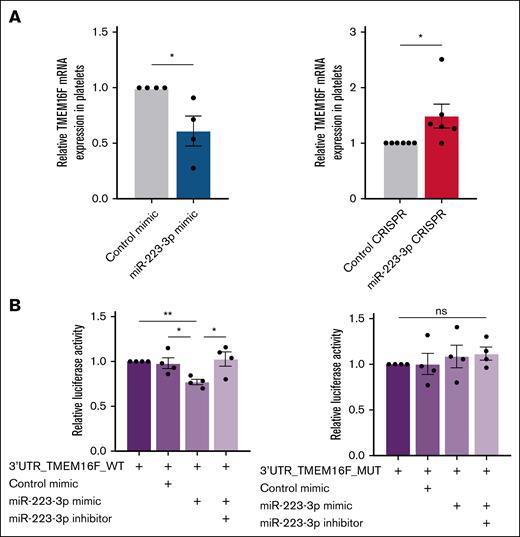

miR-223-3p regulates TMEM16F, but not SMS1 or PMCA1 mRNAs

To evaluate whether miR-223-3p regulated TMEM16F, the expression of TMEM16F mRNA using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was quantified. MiR-223-3p upregulation and downregulation in platelets induced a 47% ± 10% decrease (Figure 6A left) and a 49% ± 21% increase (Figure 6A right) in TMEM16F mRNA expression, respectively. A recent study reported increased Phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in platelets and MKs from SMS1-KO mice.19 Because SMS1 mRNA is barely detectable in human platelets,20,21 its expression in MKs was assessed, but no changes were found after miR-223-3p modulation (supplemental Figure 6). PMCA1, a calcium pump and predicted miR-223-3p target (Pictar, TargetScan, miRDB), was also evaluated, given the calcium dependence of TMEM16F activation, but it was found that its mRNA levels were unchanged (supplemental Figure 7).

TMEM16F is a direct target of miR-223-3p. (A) TMEM16F mRNA expression levels in platelets after miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right). (B) Relative luciferase activity after the co-transfection of pmirGLO-3’UTR_TMEM16F WT or MUT with a miR-223-3p mimic and/or an inhibitor in HT1080 cells. Data are from 4 to 6 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. MUT, mutant; ns, non-significant; WT, wild type.

TMEM16F is a direct target of miR-223-3p. (A) TMEM16F mRNA expression levels in platelets after miR-223-3p upregulation (left) or downregulation (right). (B) Relative luciferase activity after the co-transfection of pmirGLO-3’UTR_TMEM16F WT or MUT with a miR-223-3p mimic and/or an inhibitor in HT1080 cells. Data are from 4 to 6 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. MUT, mutant; ns, non-significant; WT, wild type.

TMEM16F mRNA is a target of miR-223-3p

Co-transfection of the plasmid pmirGLO-TMEM16F-WT and miR-223-3p mimic in HT1080 cells resulted in a 23% ± 3% reduction in luciferase activity (Figure 6B left), whereas no difference was observed when the cells were transfected with the mutated pmirGLO-TMEM16F-MUT version (Figure 6B right), suggesting that TMEM16F mRNA is indeed a direct target of miR-223-3p.

Discussion

MiR-223-3p has been associated with platelet reactivity or recurrence of ischemic events in cardiovascular patients,6,8 and the results of this study suggest that this association might be due to the regulation of procoagulant platelets. Previous reports studying the role of miRNAs in platelet function focused on miRNA upregulation only.11,22,23 In this work, we developed a CRISPR/Cas9-based approach to downregulate miR-223-3p, further reinforcing the reliability of its impact on platelet function.

CRISPR/Cas9 has been widely used to manipulate gene expression in vitro24,25 or in vivo,26,27 but targeting miRNAs presents challenges due to their small size and complex processing. To our knowledge, this work presents the first report of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated downregulation of miRNA in human MKs derived from primary cells. Our approach resulted in 43% MK transfection efficiency, comparable to that observed in the MEG-01 megakaryocytic cell line,28 and a 58% decrease in miR-223-3p expression. Moreover, the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing protocol revealed precise on-target modifications with no detectable off-target mutations, supporting the high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in the experimental model.

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of miR-223-3p modulation in megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and platelet function. miR-223-3p levels during human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation increased during its final stages, which is in line with the findings of another study.29 Therefore, when considering an increase in miR-223-3p content in MKs in the final stages of differentiation, before platelet release, we hypothesized that downregulation of miR-223-3p might have a more pronounced biological impact on platelet production than upregulation of an already relatively high level of miRNA. Indeed, only the decrease of miR-223-3p in MKs resulted in a reduction in the number of proplatelet swellings per MK, associated with reduced platelet production. The final stages of MK maturation, including proplatelet formation, are highly dependent on dynamic changes in the microtubule cytoskeleton. STMN1 is a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein that regulates microtubules by promoting their depolymerization. Indeed, STMN1 upregulation induced lower platelet production without affecting MK maturation in primary human MK.15 The qPCR analysis revealed that STMN1 mRNA, a validated target of miR-223-3p,12 was significantly increased when miR-223-3p was downregulated. Therefore, it was speculated that this may cause microtubule depolymerization in late-stage MKs, disrupting membrane budding,30 which is necessary for proplatelet swellings,31 and ultimately reducing overall platelet production.

miR-223-3p had no impact on the activation of GPIIb/IIIa after stimulation, suggesting that miR-223-3p is not involved in platelet aggregation through this receptor. P-selectin expression, however, increased after stimulation with thrombin when miR-223-3p was downregulated, a feature that has also been described in another setting.32 Importantly, P-selectin, but not activated GPIIb/IIIa, is expressed on procoagulant platelets.10 Therefore, it was hypothesized that miR-223-3p might play a role in regulating platelet procoagulant activity.

The results revealed that miR-223-3p upregulation decreased the proportion of procoagulant platelets (annexin V–positive/CD62P+ cells), with a slight but significant impact on thrombin generation. An increase in the velocity parameter, with no difference in endogenous thrombin potential, is typical of accelerated thrombin formation via platelet content release and platelet-derived extracellular vesicle formation.33 Conversely, miR-223-3p downregulation increased the proportion of procoagulant platelets but had no impact on thrombin generation. Because the magnitude of the difference in procoagulant platelets was less pronounced when miRNA levels were lower, we speculate that the standard experimental conditions of the CAT assay were not sensitive enough to reveal a difference in thrombin generation in this situation. This is consistent with findings from another study, where transfection of miR-223-3p into platelets inhibited agonist-induced microvesicle release.34 As PS exposure is accompanied by the release of microvesicles,35 it is possible that miR-223-3p regulates platelet procoagulant activity through mechanisms influencing both processes. Moreover, our findings also align with studies suggesting that miR-223-3p negatively regulates coagulation and thrombus formation.36,37 For example, miR-223-3p directly targets the 3′UTR of tissue factor mRNA, the initiator of the extrinsic coagulation pathway,36 as well as the 3′UTR of coagulation factor XIII mRNA, catalyzing the formation of crosslinks between fibrin chains, thus stabilizing the fibrin clot.37

To further investigate the mechanisms associated with the lower proportion of procoagulant platelets, we evaluated any potential changes in the calcium flux of platelet cytosol, which is essential for their generation. Our results demonstrated that miR-223-3p upregulation led to a lower intracellular calcium concentration in resting platelets. The reverse effect was observed when miR-223-3p was downregulated. However, these differences were not associated with a significant change in the proportion of procoagulant platelets before activation. The difference in intracellular calcium was no longer evident after stimulation with thrombin and convulxin. Although the impact of miR-223-3p on calcium homeostasis cannot be ruled out, calcium does not seem to be a key explanatory factor for the difference in procoagulant platelet generation. We hypothesized that miR-223-3p regulates the generation of procoagulant platelets through another mechanism.

TMEM16F, a phospholipid scramblase involved in procoagulant platelet generation,38,39 demonstrated impaired phospholipid scrambling when defective in both humans40-42 and mice.18 Furthermore, the TMEM16F mRNA was quantified using qPCR and modulations of miR-223-3p were observed to induce changes in TMEM16F mRNA levels. It was confirmed that miR-223-3p binds to the 3′UTR of TMEM16F mRNA and, as a result, TMEM16F was identified as a novel target of miR-223-3p. These findings strongly suggest that TMEM16F regulation by miR-223-3p is the main factor underlying the difference in procoagulant platelet formation. Although TMEM16F is a key player in the generation of procoagulant platelets, it cannot be ruled out that other miR-223-3p-regulated genes are involved in the generation of procoagulant platelets or other aspects of platelet reactivity. Indeed, miR-223-3p binds to the 3′UTR of the mRNA encoding the P2Y12 receptor,3,43 the target of anti-P2Y12 drugs, which may explain the poor response to P2Y12 inhibitors.8,44

This study, however, had some limitations. First, we were unable to reliably assess whether the impact of miR-223-3p on TMEM16F mRNA modulation translated into changes in protein expression. Western blotting with several antibodies (HPA038958, Merck; PA5-35240, Invitrogen; and 75-418, Antibodies Inc) produced a barely detectable TMEM16F band, likely due to its low abundance in platelets and MKs45 and to N-glycosylation, which can produce multiple bands or migration shifts.46 Second, we observed a 371-fold increase in miR-223-3p levels after transfection with a miR-223-3p mimic. Although a drastic elevation in miRNA levels can occur under certain conditions, such as a 1600-fold increase in miR-208b levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction,47 miRNA modulation in cardiovascular patients is often observed within a twofold to 150-fold range.47-50 However, miR-223-3p is already highly expressed in MKs and platelets, suggesting that small changes in miRNA levels might not result in noticeable outcomes. We strongly upregulated miR-223-3p to amplify its potential effects and detect relationships between miR-223-3p and specific cellular functions. Importantly, a CRISPR-induced 50% reduction in miR-223-3p levels led to comparable reverse effects, further reinforcing the relevance of our findings. Third, platelets are derived from healthy donors' hematopoietic stem cells, indicating that our findings may not reflect the exact biological processes, miRNA dynamics, or platelet behavior in individuals with cardiovascular diseases. Finally, clinical association studies measured the levels of circulating, cell-free, miRNAs and the directionality of effects may be different when miRNAs are assessed within platelets.

Platelet aggregation properties have been the target of antiplatelet drugs for some years, but low-dose anticoagulation (rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily) is now considered for selected patients.51,52 However, this strategy is associated with an increase in major bleeding,53,54 and we speculate that the proportion of procoagulant platelets modulates the risk of bleeding events in low-dose anticoagulation. Knowing a patient’s miRNA profile could help to personalize antithrombotic treatment according to their individual platelet reactivity profile, which warrants further research on such hypotheses and personalized approaches. Finally, procoagulant platelets are also implicated in deep vein thrombosis55 and bleeding phenotypes.56,57 Identifying biomarkers associated with the generation of procoagulant platelets may therefore have implications beyond a prognostic value or the tailoring of antithrombotic drugs in ischemic cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cécile Gameiro (Flow Cytometry Core Facility, University of Geneva) for her assistance with flow cytometry and helpful discussions, and Nicolas Liaudet (Bioimaging Core Facility, University of Geneva) for developing scripts for identification of megakaryocytes and proplatelets from bright-field microscopy images. The authors also thank Yves Cambet (READS Unit of the R3 Core Facility, University of Geneva) for assistance with the plate reader, as well as the production and quality-control staff at Geneva’s blood transfusion center.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation for Scientific Research (grant 310030_196864) and the Edmond J. Safra Fund (unrestricted research grant).

Authorship

Contribution: J.C.-G., S.D.-G., J.-L.R., and P.F. designed the study; J.C.-G., S.N., and S.D.-G. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; J.C.-G., S.D.-G., and P.F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors revised the intellectual content and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pierre Fontana, Division of Angiology and Hemostasis, Geneva University Hospitals, Rue Gabrielle-Perret-Gentil 4, CH-1205 Geneva, Switzerland; email: Pierre.Fontana@hug.ch.

References

Author notes

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Pierre Fontana (Pierre.Fontana@hug.ch).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.