Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited monogenic red blood cell disorder affecting millions worldwide. SCD causes vascular occlusions, chronic hemolytic anemia, and cumulative organ damage such as nephropathy, pulmonary hypertension, pathologic heart remodeling, and liver necrosis. Coagulation system activation, a conspicuous feature of SCD that causes chronic inflammation, is an important component of SCD pathophysiology. The key coagulation factor, thrombin (factor IIa [FIIa]), is both a central protease in hemostasis and thrombosis and a key modifier of inflammation. Pharmacologic or genetic reduction of circulating prothrombin in Berkeley sickle mice significantly improves survival, ameliorates vascular inflammation, and results in markedly reduced end-organ damage. Accordingly, factors both upstream and downstream of thrombin, such as the tissue factor–FX complex, fibrinogen, platelets, von Willebrand factor, FXII, high-molecular-weight kininogen, etc, also play important roles in SCD pathogenesis. In this review, we discuss the various aspects of coagulation system activation and their roles in the pathophysiology of SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited monogenic red blood cell (RBC) disorder affecting over 100 000 Americans and 15 to 20 million people worldwide.1,2 The often devastating disease is characterized by RBC sickling; chronic hemolytic anemia; priapism; infections; episodic vaso-occlusion associated with severe pain and inflammation; acute and cumulative organ damage that manifests as stroke, acute chest syndrome, sickle lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, nephropathy, and end-stage renal disease; and other morbidities.3 Patients with SCD have high health care utilization costs of over 1 billion dollars per year in the United States alone4 and several billion dollars worldwide. The average life expectancy of affected patients is foreshortened to 45 years in the United States,3 but most children born in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia die before 5 years of age. The prevention of early death from infections, stroke, and acute chest syndrome has changed the natural history of the disease in resource-rich countries. Now cardiac,5 pulmonary,6 and renal7 sequelae are emerging as the most common cause of death in SCD.8 Beyond providing symptom relief and preventing infections, therapeutic options are limited to chronic transfusions, hydroxyurea (a drug that induces the antisickling fetal hemoglobin), l-glutamine, or crizanlizumab (an antibody against P-selectin).9,-11 The only curative option is an allogenic bone marrow transplant (BMT), and this option is available only to 15% of patients with a matched donor.12 Although the molecular basis of SCD has been known for decades, the basis underlying its pathogenicity and organ damage have not been completely elucidated.

SCD is caused by a single-nucleotide mutation: A to T in the sixth codon that changes glutamic acid to valine of the β-globin gene. Homozygosity of this mutation causes polymerization of sickle hemoglobin (HbS) tetramers within RBC under hypoxia. Abnormally large hemoglobin polymers convert doughnut-shaped RBCs to a nondeformable, abnormal sickle shape. Repeated cycles of RBC sickling can cause recurrent vaso-occlusion and frequent infarctions.2,13 Sickle RBC-mediated coagulation hyperactivation and endothelium dysfunction lead to inflammation, vascular leakage, and thrombosis,14,,-17 which may cause end-organ damage in SCD. However, a definitive understanding of coagulation-mediated pathologies of SCD at the mechanistic level remains a major basic science and clinical gap and an active area of research.17

The role of coagulation factors in the pathogenesis of SCD

Although vascular occlusions promote thrombosis, coagulation is activated in patients with SCD in the absence of vascular occlusions, as evidenced by increased tissue factor (TF), elevated levels of thrombin generation, and platelet and endothelial activation18,,-21 ; increased monocyte- and endothelial cell (EC)-derived procoagulant microparticles; as well as RBC-platelet and neutrophil-platelet aggregates in the circulation.16,17 Additionally, anionic phospholipids, primarily phosphatidylserine, are exposed on the surface of RBCs, which support coagulation activity. Patients who have developed SCD-associated pulmonary hypertension have marked endothelial dysfunction, as measured by soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), which correlates with the degree of hemolysis, suggesting that hemolysis directly or indirectly activates ECs.22,23 We have summarized the coagulation factor–mediated pathogenesis of SCD in Table 1.

TF and FXa

TF is a transmembrane receptor for factor VII/VIIa (FVII/FVIIa), which is normally expressed by vascular smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and adventitial fibroblasts in the vessel wall.24,25 The endothelium physically separates TF from its circulating ligand FVII/FVIIa and prevents inappropriate activation of the coagulation cascades. The exposure of extravascular TF occurs due to breakage of the endothelial barrier. The TF-FVII/FVIIa complex initiates the coagulation cascade through activation of FX to FXa, which converts prothrombin (FII) to thrombin (FIIa). Thrombin subsequently promotes the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and platelet activation resulting in clot formation.26,-28

TF is constitutively expressed by ECs of SCD patients.29,30 Circulating ECs in SCD abnormally express TF, and its expression significantly increases with acute vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC).29,31 Microparticles (MPs) derived from RBCs and monocytes are significantly elevated in SCD patients both during VOC and at steady state, as compared with healthy subjects, whereas platelet- and EC-derived MPs are elevated in SCD patients only during VOC32,33 and shorten the plasma-clotting time in patients compared with control subjects.34 This increased hypercoagulation by RBCs and platelet MPs is mediated via externalized phosphatidylserine, and monocyte and EC MPs via TF expression.32,-34 Inhibition of TF in sickle mice reduces inflammation and endothelial injury, as evidenced by reduced plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6), serum amyloid P, and sVCAM-119 ; reduced systemic inflammation; and cardiac hypertrophy.35 These data suggest that targeting TF may reduce vascular inflammation and organ damage in SCD.35 TF mediates activation of FX (FXa) which is also a viable downstream target of TF activation in SCD.36 In fact, oral FXa inhibitors rivaroxaban (NCT02072668) and apixaban (NCT02179177) are in clinical trials in SCD (Table 2 and https://clinicaltrials.gov/). The goal of these studies is to inhibit FXa to reduce inflammation, coagulation, and EC activation, and improve microvascular blood flow in patients with SCD, thus reducing VOC. Of note, none of these studies have assessed organ damage as the end point, which may be important to consider given that anticoagulants have historically not reduced or prevented acute VOC. Because FXa inhibitors can predispose patients to risk of bleeding, proper monitoring and dose adjustment is likely necessary. In fact, a small dose of FXa inhibitors, which mildly prolong the generation of thrombin (minimize the bleeding risk) may suffice, as we have shown that sickle mice with a 1.25× prolongation in prothrombin time had significant amelioration of organ damage without bleeding complication.15

Thrombin

The TF-FVIIa cascade and the intrinsic coagulation cascade (involving FXIa, FIXa, and FVIIIa) activate FXa, which converts prothrombin (FII) to thrombin (FIIa), which cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin. Fibrin polymer in combination with activated platelets forms the clot.28 Thrombin not only plays a seminal role in the context of vascular injury to limit blood loss, but is also closely connected with inflammation, and bridges the gap between the coagulation and inflammatory systems.37,38

Thrombin controls inflammatory processes via multiple proteolytic targets and pathways. Through proteolytic activation of 7-transmembrane G protein–coupled receptors protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), PAR-3, and PAR-4, thrombin can directly activate ECs, platelets, fibroblasts, and other cell types. This leads to the secretion of cytokines and chemokines (IL-1, IL-6, macrophage inflammatory protein 1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 3, and platelet factor-4) and changes the leukocyte-adhesive properties (increased expression of P-selectin, CD40 ligand), which are important in leukocyte trafficking and activation.39,,,,,-45 In addition, the proteolytic activity of thrombin can activate a wide spectrum of inflammatory effectors, including C5, thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, protein C, and osteopontin.46,-48 It has been increasingly appreciated that thrombin is central to both physiological inflammatory events (eg, antimicrobial host defense) and inflammation-driven pathological processes, including neuroinflammatory disease, vessel wall disease, and inflammatory joint, kidney, and lung diseases.49,,,-53 SCD patients show elevated markers of thrombin generation as indicated by the presence of thrombin fragment 1.2, thrombin-antithrombin complexes, fibrinopeptide A, and D-dimers.54

Several clinical trials were conducted in SCD patients with thrombin inhibitors mainly to reduce acute VOC. Heparin administration in 4 SCD patients with minidoses (5000-7500 units every 12 hours) was followed for VOCs for 12 months, which were compared in the same patients without heparin for 12 months. The days of hospitalization per year and hours spent in emergency rooms per year were used as a measure of VOC outcome. VOCs were reduced to 73% and 74%, respectively, when patients were followed for 8.7 years on heparin and 12 years without heparin. However, the pain recurred in the patients when heparin was not administered.55 Tinzaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, was used in a randomized phase 3 trial in 127 SCD patients for 7 days. Compared with the similar number of placebo-treated patients, the tinzaparin-treated patients showed a significant reduction in number of days with severe pain score, overall duration of painful crisis, and days of hospitalization, suggesting that thrombin inhibitors are useful in VOC.56 However, the requirement of chronic administration of a parenteral thrombin inhibitor has hindered its applicability. Warfarin, an oral anticoagulant, was tested in SCD patients. In fact, warfarin was the first anticoagulant tested in clinical trials in SCD and has provided modestly reduced frequency of VOC (1.3-0.9 per year).57 Its long-term administration was shown to heal leg ulcers, but did not affect VOC (Table 2).58 It is to be noted that warfarin inhibits both vitamin K–dependent procoagulant proteins (FII, FVII, FIX, and FX) and anticoagulant proteins (protein S and protein C), and, hence, can be a double-edged sword. Moreover, there were large fluctuations in prothrombin times with warfarin in these studies (which were done >7 decades ago, when the international normalization ratio was not routinely monitored), resulting in bleeding complications.

The more recently discovered oral thrombin inhibitors, like dabigatran, may not have the aforementioned limitations of warfarin or heparin. In preclinical studies, dabigatran has been found to limit local lung inflammation, demonstrating the previously established link of thrombin with inflammation, although deletion of PAR-1 (a substrate of thrombin) does not affect the systemic inflammation in this short-term study.59 We have assessed the role of thrombin in the pathogenesis of SCD in a mouse model.15 A prothrombin antisense oligonucleotide gapmer administered to Berkeley sickle mice, which reduced the thrombin level to 10% of the normal, resulted in a significant improvement of their survival in the initial 15 weeks. However, this short-term study did not find any difference in organ damage in the SCD mice. To assess the effect of thrombin in inducing long-term organ damage, sickle chimera of Berkeley mice were generated by BMT into the thrombin mutant mice, which express 10% of the level of thrombin compared with the healthy mice. One year after BMT, significant improvement in SCD-associated end-organ damage (such as nephropathy, pulmonary hypertension, inflammation, liver function, inflammatory infiltration, and microinfarctions) was demonstrated in sickle chimeric mice due to genetic reduction of thrombin generation.15 Although these human and murine studies suggest that lowering thrombin chronically may be beneficial, none of the studies have defined the molecular mechanism of thrombin-induced pathogenesis in SCD. It is likely that thrombin exerts detrimental effects through activating platelets or ECs through proteolytic cleavage of PARs, or due to enhanced fibrin/clot formation. Activated platelets and EC-secreted inflammatory cytokines likely contribute to the organ damage in SCD. Alternatively, thrombin, by increasing fibrin formation, promotes microvascular thrombosis or mediates inflammation via fibrin(ogen)-mediated leukocyte recruitment. Overall, thrombin signaling is a powerful modifier of SCD-induced end-organ damage, and a detailed mechanistic study could decipher novel therapeutic targets to ameliorate SCD pathologies.

Because thrombin plays a vital role in hemostasis, targeting thrombin will weaken the blood-clotting ability in patients and can increase the risk of bleeding, requiring careful monitoring. Conceivably, specific targeting and manipulation of the downstream signaling pathways of thrombin (such as PAR-1 with small molecule inhibitors such as vorapaxar60 or atopaxar,61 or PAR-4 with BMS-98612062 ) may limit inflammation and organ pathologies without significant compromise of the hemostatic functions of thrombin and its associated coagulation factors, and are worth exploring, which may be beneficial in SCD.

Fibrinogen

Fibrin(ogen) is 1 of the main thrombin substrates that plays a crucial role in hemostasis and thrombosis. During normal blood clotting, thrombin converts soluble fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin. The fibrin strands are then cross-linked by FXIII to form a blood clot in cooperation with platelets.28 However, fibrin(ogen) also plays important roles in physiologic and pathologic inflammatory processes. Fibrin(ogen) controls a myriad of cellular activities including mitogenic, chemotactic, and immunoregulatory activities through both integrin and nonintegrin receptors.63,,-66 At least 1 feature of fibrin(ogen) driving inflammatory events is the leukocyte integrin receptor, αMβ2, which binds to the γ-chain of immobilized fibrin and regulates leukocyte activities.67 In addition, fibrin(ogen) acts as a bridge between platelets and platelet-neutrophil/monocyte aggregates, in part through integrin receptor α2bβ3. The aggregates have been implicated as a powerful driver of inflammation and pathologies of SCD.68,,-71 Plasma fibrinogen levels in SCD patients are an indicator of hypercoagulability.72 Plasma fibrinogen concentration was estimated in SCD patients in steady state and during episodes of pain crisis. Fibrinogen concentrations were higher in sickle patients in the steady state than healthy control subjects.72 However, pain crisis was associated with a significant increase in both plasma fibrinogen and whole-blood viscosity. Increased fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation may play a role by raising blood viscosity during pain crisis in SCD patients.73 However, fibrinogen-deficient SAD mice (transgenic mice expressing SAD [HbS, HbAntilles, and HbD]) showed worse mortality than SAD mice with an intact fibrinogen gene,74 suggesting that fibrinogen may have a protective role in SCD. In contrast, Berkeley sickle mice bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells transplanted into fibrinogen-deficient mice resulted in a decreased number and size of liver infarcts. However, the fibrinogen-deficient chimeric sickle mice still developed other SCD-associated organ pathologies, including focal sites of prominent vascular congestion that are likely due to persistent endothelial injury and inflammation.75 These conflicting findings may be due to differences in mouse models of SCD or, perhaps, fibrinogen may be necessary for tissue repair in SCD. Targeting receptors of fibrin(ogen) α2bβ3 with antagonists such as abciximab provided benefit in patients with refractory unstable angina in relation to serum troponin T levels,76 or eptifibatide-reduced mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes.77 Eptifibatide, however, did not provide any benefit for acute pain crisis in SCD patients,78 although its long-term effects on organ damage have not been studied in SCD.

Fibrinolysis is the degradation of fibrin clots by plasmin, which cleaves the fibrin mesh, forming fibrin degradation products (such as D-dimer) that are cleared by other proteases or by the kidney and liver.79 It has been reported that fibrinolysis is increased in SCD patients at steady state, as compared with healthy subjects, and is further increased during VOC.80,-82 Hydroxyurea treatment decreases the thrombin-antithrombin complexes and D-dimer concentration in SCD patients, but it is unknown whether this is a secondary effect from improvement of overall disease phenotype.83 It is to be noted that plasminogen-deficient SAD mice had similar mortality compared with SAD mice with an intact plasminogen gene.74

Platelets

Platelets are not only essential components of the coagulation system but can also promote inflammation and thrombosis. Although platelets are inactive in the circulation, their activation is triggered when a break in the endothelium exposes collagen. In addition, thromboxane A2 via COX-1, adenosine diphosphate via P2Y12, and thrombin via PAR-1, PAR-3, and PAR-4 can trigger platelet activation, causing the release of bioactive cargo stored in the platelet granules.41,42,84

Platelet counts are higher in SCD patients under the steady-state condition and are further increased during VOC.70,85 Activated platelets promote adhesion of sickle RBCs to vascular endothelium and contribute to thrombosis and pulmonary hypertension in SCD patients.85 Platelets can also bind to RBCs, monocytes, and neutrophils to form aggregates.69,70 Chronic platelet activation and aggregation are observed in SCD patients, which are evident by the expression of platelet activation markers.70,85 Platelet agonists such as thrombin, adenosine 5′-diphosphate, and epinephrine are also increased in plasma. A significant increase in platelet-monocyte and platelet-neutrophil aggregates is observed in patients and mice with SCD.68 Pretreatment of SCD mice with antiplatelet agents, clopidogrel, or P-selectin antibody reduce formation of aggregates and decreases lung vascular pathology.68 Treating with both hydroxyurea and the AKT2 inhibitor efficiently reduces neutrophil adhesion and platelet-neutrophil aggregates in venules of Berkeley sickle mice challenged with tumor necrosis factor α or hypoxia and reoxygenation. This treatment also benefits acute vaso-occlusion and contributes to the survival of SCD mice.86

SCD patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) associated with increased hemolysis exhibit significant platelet activation and suggest that hemolysis is a potential pathologic mechanism that contributes to its development.85 Cell-free hemoglobin can trigger platelet activation. Another key inhibitor of platelet activation is nitric oxide (NO). However, SCD patients generate a high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which reacts with the NO in the vasculature, which produces peroxynitrite and depletes the bioactive NO. Impaired NO bioavailability represents the central feature of endothelial dysfunction and is a common denominator in the pathogenesis of SCD, especially SCD-associated PAH.87 Both ROS and peroxynitrite are highly reactive, which can damage components of the cell including lipids, thiols, amino acid residues, DNA bases, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants.88,89 The role of NO in this pathophysiologic mechanism is further highlighted by the observation that sildenafil can decrease PAH-associated platelet activation in patients with SCD. Hence, the interaction between hemolysis, decreased NO bioavailability, and pathologic platelet activation likely contributes to thrombosis and pulmonary hypertension in SCD.85,90 Tablin and his colleagues reported that platelet activation markers, such as P-selectin expression on circulating platelets, increased plasma concentrations of platelet factor 4 and thromboglobulin; additionally, increased numbers of circulating platelet MPs are present in patients with SCD.70,91 We have summarized the platelet-mediated pathogenesis of SCD in Table 1.

Although platelets are a reasonable target for treating SCD patients, none of the antiplatelet drugs provide beneficial effect in short-term studies. The platelet inhibitor aspirin did not show any consistent benefit in preventing VOC or upregulating hemoglobin in SCD patients in 4 of the clinical trials (Table 2).92,-94 Although platelet inhibitor prasugrel inhibited platelet activity, it did not significantly reduce the VOC in children and adolescents with SCD (Table 2) (NCT01476696, NCT01167023, NCT01794000, NCT01178099, and NCT01430091).95,-97 Piroxicam, ticagrelor, and ticlopidine showed modest to disappointing results in reducing the pain of VOC in SCD patients (Table 2).98,-100 Although these drugs were largely unsuccessful in reducing acute VOC events, they may possibly provide benefit to chronic organ damage, which has not been studied as an end point.

VWF

von Willebrand factor (VWF) is the largest coagulation factor produced by ECs, megakaryocytes, and subendothelial connective tissues. VWF plays an important role in blood coagulation by binding to FVIII (which increases its stability) as well as the platelet glycoprotein Ib (GPIb)/FIX/V receptor via collagen and the α2β3 receptor on activated platelets. Mutations in the VWF gene that result in reduced VWF or altered VWF properties cause a bleeding disorder.101,-103 The role of VWF in the pathogenesis of SCD is still unclear. Multimeric VWF increases the adhesion of sickle RBCs to endothelium twofold to 27-fold more than the healthy RBCs.104 VWF activity was reported to be augmented in SCD patients during VOC and was associated with the increased markers of inflammation without a pronounced ADAMTS-13 deficiency.105 VWF also increases in SCD patients with sleep hypoxemia.106 HbS present in the blood binds to VWF, which prevents its degradation by ADAMTS-13 resulting in accumulation of VWF in the circulation and endothelium.107 Therefore, HbS-VWF interaction can be explored as a potential therapeutic target for VOC in patients with SCD.

Contact activation system

In the contact activation system (CAS), coagulation FXII, prekallikrein (PK), and high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK) bind to the EC surface resulting in FXII activation (FXIIa), which in turn initiates blood coagulation through cleavage and activation of FXI.108 The CAS has been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammation, hypertension, endotoxemia, and coagulopathy of sepsis, arthritis, and enterocolitis, which suggest the role of CAS in host defense and innate immunity.109 The CAS can also activate the kinin-kallikrein system when activated plasma kallikrein cleaves HK releasing a peptide known as bradykinin (BK). BK and its derivatives bind to its receptors, B1 and B2 to cause inflammation.108,110 CAS deficiency, however, is not associated with any bleeding disorder.110 FXIIa and HK contribute to thrombin generation at steady state, and FXIIa contributes to the enhanced thrombin generation observed in VOC.111 HK deficiency reduces chronic inflammation and cardiac hypertrophy, protects from kidney damage, and improves the lifespan of mice with SCD.112 Therefore, targeting CAS may provide beneficial effects in SCD, without affecting hemostasis.

NETs

Neutrophils are the most abundant type of white blood cells (WBCs), comprising 60% to 70% of circulating WBCs, and are the first line of defense against infection and kill invading pathogens through phagocytosis and secretion of antimicrobials.113 Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are networks of extracellular fibers, primarily composed of DNA from neutrophils, which bind, trap, and kill extracellular pathogens without phagocytosis while minimizing damage to the host cells.114 Recent studies have found that small vessel vasculitis,115 deep vein thrombosis,116 and transfusion-related acute lung injury cause NET formation in the absence of pathogens.117 NET formation was induced in SCD mice treatment with tumor necrosis factor α. NETs were detected in the lungs, which caused injury to the lung vasculature. Circulating free heme can also stimulate NET formation by activating neutrophils.118 NET formation in SCD mice was shown to be reduced by treating mice with DNase I (which lyses them) or with hemopexin (which scavenges heme). Targeting NET formation, therefore, holds the potential of improving the injury induced by inflammation in SCD.118

Complement system activation

The complement system is a part of the innate immune system. The complement proteins are synthesized in the liver and secreted in the bloodstream as inactive precursors.119 Activation of all 3 complement pathways (classical, alternative, and lectin) generates the protease C3-convertase, which initiates an amplification cascade to further cleave other complement proteins to form C5b-9, the membrane attack complex (MAC). C3b augments phagocytosis through opsonizing microbes, C3a and C5a promote inflammation by chemotaxis of neutrophils and macrophages, and the MAC ruptures the cell wall of pathogens.120 The complement system likely contributes to the pathogenesis of SCD through the alternative pathway, which does not need antibody-antigen interaction for activation, but can be activated by sickle RBCs with exposed phosphatidylethanolamine or phosphatidylserine.121 The complement protein Bb, C3a, and C5a were found in the plasma of SCD patients during VOC, where they can contribute to inflammation and vasculopathy.121,-123 It was recently reported that hemolysis of RBCs and its degradation products, specifically cell-free heme, can trigger complement activation.124 The MAC is significantly increased in SCD patients compared with healthy human subjects, and particularly in older patients.125 Therefore, complement activation can contribute to inflammation, endothelial damage, and vascular injury in SCD.

Possible mechanism of coagulation-mediated inflammation and chronic organ damage in SCD

Conspicuous features of SCD include chronic inflammation and coagulation system activation. Substantial deficits remain in understanding the pathophysiology of SCD. Platelet activation and endothelial dysfunction, coupled with inflammatory processes, have been proposed to be significant drivers of SCD pathogenesis. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which the coagulation system contributes to the pathogenesis of SCD remains poorly defined.

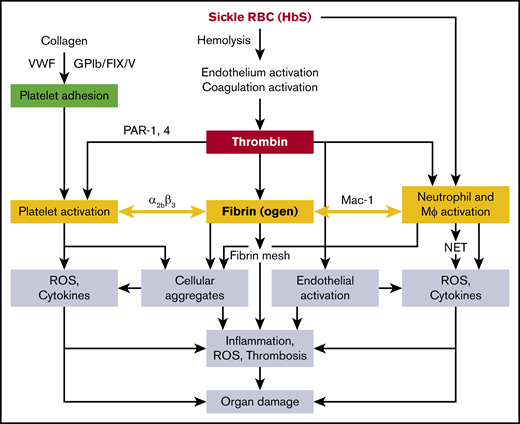

Subendothelial collagen, VWF, and GPIb/FIX/V cause adhesion of platelets, which are activated by thrombin through PARs; platelets also express P-selectin, which interacts with leukocytes126 via the platelet integrin αIIbβ3127 and likely contributes to cellular aggregate formation. Pharmacologic inhibition of αIIbβ3 abolishes the interaction of platelets with neutrophils.128 The integrin αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18 or Mac-1) receptor of monocytes and neutrophils interacts with platelets through fibrinogen.129 A mouse line expressing a mutant form of fibrinogen in which the amino acids in the binding motif (N390RLSIGE396) of the γ-chain were replaced with alanine residues had normal plasma fibrinogen and clotting function,130 but did not support αMβ2-mediated adhesion of leukocytes (neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages), and therefore had defects in the host inflammatory response.130 Chimeric sickle mice lacking the αMβ2-binding motif of fibrinogen showed reduced WBC ROS and inflammatory cytokines, and were significantly protected from glomerular pathology and albuminuria.131 It is therefore conceivable that fibrin(ogen) acts as a bridging molecule between the αMβ2 receptor of WBCs and the αIIbβ3 receptor on platelets, thereby promoting platelet-leukocyte aggregates, commonly seen in SCD.130 Platelet activation and platelet-neutrophil aggregates have been shown to exert detrimental effects in SCD mice,68 likely mediated via secretion of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and increased oxidative stress. Overall, multifactorial and interlinked pathophysiology contributes to organ injury (including the release of free heme from hemolysis of sickle RBCs), which accentuates endothelial dysfunction, vascular leakage, and NET formation caused by the inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, ROS, and activated platelet-neutrophil aggregates (Figure 1). Deciphering these mechanisms may lead to the development of novel therapeutics targeting the coagulation system that spare their hemostatic function.

Proposed mechanisms of sickle RBC (HbS)–mediated coagulation system activation in the organ pathologies of SCD. Mϕ, macrophage.

Proposed mechanisms of sickle RBC (HbS)–mediated coagulation system activation in the organ pathologies of SCD. Mϕ, macrophage.

Conclusion

A connection between sickle RBCs, the coagulation system, and SCD pathobiology has long been speculated. Activation of the coagulation system and inflammation are the prominent features of SCD. Targeting coagulation factors, particularly thrombin and TF, is beneficial for organ pathology in mouse models of SCD. Although several clinical trials have been conducted targeting the coagulation system, specifically TF and platelets for a short period of time to observe the effect in SCD patients, no one has examined the long-term effects on organ damage. We speculate that targeting coagulation factors with small molecule inhibitors with careful long-term dosing may reduce the cumulative organ damage in SCD patients. However, further studies are needed that carefully dissect the mechanistic pathways, so that safe therapeutic targets can undergo clinical testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew J. Flick, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, for critically reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL112603 (P.M.), and start-up funding from Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation and a University of Cincinnati pilot translational grant (M.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.N. and P.M. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Md Nasimuzzaman, Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center, 240 Albert Sabin Way, Mail Code #7013, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: md.nasimuzzaman@cchmc.org.