Key Points

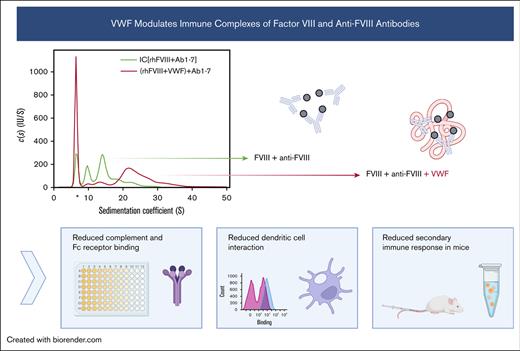

Immune complexes of factor VIII and anti-FVIII antibodies incorporated VWF, changing their structural and functional properties.

Addition of VWF to FVIII suppressed the FVIII-specific recall response in vitro and in vivo.

Abstract

Achieving tolerance toward factor VIII (FVIII) remains an important goal of hemophilia treatment. Up to 40% of patients with severe hemophilia A (HA) develop neutralizing antibodies against FVIII, and the only proven treatment to achieve tolerance is infusion of FVIII over prolonged periods in the context of immune tolerance induction. Here, we addressed the role of von Willebrand factor (VWF) as a modulator of anti-FVIII antibody effector functions and the FVIII-specific recall response in an HA mouse model. Analytical ultracentrifugation was used to demonstrate formation of FVIII-containing immune complexes (FVIII-ICs). VWF did not fully prevent FVIII-IC formation but was rather incorporated into larger macromolecular complexes. VWF prevented binding of FVIII-ICs to complement C1q, most efficiently when it was preincubated with FVIII before the addition of antibodies. It also prevented binding to immobilized Fc-γ receptor and to bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. An in vitro model of the anti-FVIII recall response demonstrated that addition of VWF to FVIII abolished the proliferation of FVIII-specific antibody-secreting cells. After adoptive transfer of sensitized splenocytes into immunocompetent HA mice, the FVIII recall response was diminished by VWF. In summary, these data indicate that VWF modulates the formation and effector functions of FVIII-ICs and attenuates the secondary immune response to FVIII in HA mice.

Introduction

Congenital hemophilia A is an X-linked hereditary bleeding disorder characterized by reduced or absent activity of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). Infusion of therapeutic FVIII protein is used to treat or prevent bleeding but results in the formation of neutralizing antibodies, called inhibitors, in up to 40% of patients.1 Although nonfactor replacement therapy like emicizumab has become available,2,3 the formation of inhibitors is still the major complication of hemophilia treatment, and achieving immune tolerance toward foreign FVIII is an important treatment goal.4

The only proven way to achieve tolerance toward FVIII in patients with established inhibitors is immune tolerance induction (ITI), a treatment that involves repeated infusion of FVIII over prolonged periods of time. Successful ITI leads to disappearance of inhibitors, normalization of FVIII pharmacokinetics, and restoration of its hemostatic capacity. According to the international ITI study, 70% of patients achieve success over a period of 3 years.5 The high cost and treatment burden of ITI create a significant unmet medical need around tolerance induction in hemophilia.

Uncertainty exists around the choice of FVIII products for ITI. Plasma–derived FVIII products contain variable amounts of von Willebrand factor (VWF), whereas recombinant products are devoid or contain only trace amounts of VWF. FVIII is bound to VWF in a tight, noncovalent complex involving mainly FVIII’s C1 domain but also the C2 domain and a short acidic peptide (a3) at its light-chain N-terminus.6,7 This interaction is important for FVIII stability in the circulation but also determines how it is presented to the immune system.8,9 VWF reduces FVIII uptake and modulates peptide presentation by antigen-presenting cells (APC),10,11 suggesting an immunoprotective effect of VWF toward therapeutically administered FVIII.12

Clinical data support the notion that VWF can reduce the immunogenicity of FVIII. The randomized SIPPET study found that previously untreated patients treated with plasma–derived FVIII-containing VWF had a lower incidence of inhibitors than those treated with recombinant FVIII.1

Whether the presence of VWF plays a role in achieving and maintaining success of ITI has long been debated and remains unclear.13 During the secondary immune response, when inhibitors and FVIII-specific memory B cells are already abundant, the uptake and presentation of antigen may occur differently and the relevance of VWF may change. Antibodies are considered as “natural adjuvants,”14 and, in fact, immune complexes of FVIII and anti-FVIII immunoglobulin G (IgG; FVIII-ICs) promoted the endocytosis of FVIII by murine bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs).15 Although this interaction appears to be primarily driven by Fc-γ receptors, immune complexes are also expected to interact with the complement system, which could further enhance antigen uptake and presentation.

VWF is known to mitigate the neutralization capacity of (some) FVIII inhibitors in vitro.16 The relevance of this observation during ITI is unclear. We were therefore interested to study how VWF interacts with FVIII in the presence of inhibitors, and whether this interaction can affect downstream functions of the secondary immune response, including Fc receptor binding, complement fixation, BMDC activation, and the stimulation of FVIII-specific plasmocytes, or antibody-secreting cells (ASCs).

Materials and methods

FVIII, VWF, anti-FVIII antibodies, and FVIII-ICs

Recombinant human FVIII (rhFVIII) was octocog-α (Advate, Takeda, Vienna, Austria, if not otherwise noted). FVIII-free, plasma–derived human VWF was obtained from Biotest AG (Dreieich, Germany). Dimeric D’D3 fragment of VWF (D’D3) was kindly provided by Octapharma AG (Lachen, Switzerland). Seven different monoclonal anti-FVIII antibodies raised against different epitopes of FVIII (Ab1-7; Table 1) were purchased from Green Mountain Antibodies (Burlington, VT) and SEKISUI Diagnostics (Burlington, MA). An antibody pool (Ab1-7) was generated by combining these monoclonal anti-FVIII Abs in equal amounts. Polyclonal anti-FVIII antibodies (Ab-poly) were raised in F8−/− mice (n = 10, anti-FVIII titer by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] 1:40 480) and used diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). FVIII-ICs were generated by mixing rhFVIII with anti-FVIII antibodies in the indicated concentrations at 37°C for 30 minutes.

FVIII-IC characterization by analytical ultracentrifugation

Monoclonal anti-FVIII antibodies, alone or in combination, were conjugated with a Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) labeling kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibody concentration and conjugation were assessed using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop One, Thermo Fisher Scientific). FVIII-ICs were generated using a 1.1:1 molar ratio of rhFVIII and AF488-labeled Ab1-7 or single antibodies, as indicated. To assess the impact of VWF on FVIII-IC formation, rhFVIII was incubated with VWF at molecular ratio of 1:50 or equal to VWF amount of human serum albumin (HSA; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) before the addition of antibodies. In some experiments, the incubation was reversed, as indicated.

Runs were carried out in a ProteomeLab XL-I (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with a fluorescence detection system (Aviv Biomedical Inc, Lakewood, NJ), using an An-50 Ti rotor at 30 000 rpm and 20°C. For excitation, a 488-nm 10-mW solid-state laser was used, and emission was detected through a dichroic and a 505-to-565-nm bandpass filter. Programming of the centrifuge and data recording were performed using AOS2 software (Aviv Biomedical Inc). Special cell housings (Nanolytics, Potsdam, Germany) were used that allowed the placement of 3-mm charcoal-filled Epon double-sector centerpieces directly beneath the upper window of the cell.17 All experiments were performed in PBS (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4; 2.68 mM KCl; and 0.14 M NaCl) supplemented with 1 μM bovine serum albumin (BSA) using a sample volume of 100 μL. For data analysis, a model for diffusion-deconvoluted differential sedimentation coefficient distributions implemented in the program SEDFIT was used.18 Sedimentation coefficients were not corrected to s20,w and are given as experimental s-values. Figures were prepared using the program GUSSI.19 Addition of VWF decreased the sedimentation coefficient of antibody regardless of rhFVIII. Enhanced green fluorescent protein–cofilin was used as a control protein and found to decrease sedimentation coefficients by the same rate (data not shown). Therefore, diffusion-deconvoluted differential sedimentation coefficient distributions were corrected by a factor determined by comparing the s-values of antibody in the absence and presence of the corresponding VWF concentration.

Binding of FVIII-ICs to complement and Fc-γ receptor

FVIII-ICs were generated with rhFVIII (3 IU/mL or 2.1·10−9 mol/L) incubated with or without VWF (0-20 IU/mL or 0-200 μg/mL) and afterward with anti-FVIII antibodies (0.5 μg/mL or 3.3 × 10−9 mol/L). In some experiments, the incubation was reversed, as indicated. HSA (0-200 μg/mL) was used as a control plasma-derived protein to confirm the specificity of VWF effect. Moreover, to assess the influence of the whole VWF molecule on FVIII-IC binding, D’D3 was applied instead of VWF at a concentration ranging from 0 × 10−9 mol/L to 55 × 10−9 mol/L. Solid phase binding of FVIII-IC to complement component C1q and Fc-γ receptor CD32 was assessed using ELISA, as previously described.20,21 Human C1q (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) or human soluble CD32 (5 μg/mL; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was immobilized to 96-well flat-bottom plates (Nunc MaxiSorb, Copenhagen, Denmark). After blocking with 5% BSA in PBS, plates were incubated with samples at room temperature (RT) for 2 hours. Subsequently, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody was added (donkey anti-mouse IgG HRP; Chemicon, Hampshire, United Kingdom; dilution, 1:1500) at RT for 1 hour. The color reaction was initiated using tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) and was stopped with 1 M hydrochloric acid (Sigma Aldrich).

Binding of FVIII-IC to BMDCs

Ab1-7 or Ab-poly, purified using Nab Protein G Spin Kit and Zeba Spin Desalting Columns, were conjugated using Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) antibody labeling kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Concentration and conjugation were assessed using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop One). FVIII-ICs were generated by incubating rhFVIII (4 IU/mL or 3 × 10−9 mol/L) with or without VWF (4 IU/mL) and labeled Ab1-7 (10 μg/mL or 7 × 10−8 mol/L). Alternatively, FVIII-ICs were generated by incubating rhFVIII (10 IU/mL or 7 × 10−9 mol/L) with or without VWF (10 IU/mL) and subsequently with labeled Ab-poly (14 μg/mL or 9 × 10−8 mol/L). In some experiments, the incubation was reversed, as indicated. HSA (40 μg/mL) was utilized as an unrelated plasma-derived protein in place of VWF, as specified. BMDCs were generated as previously described.20 After harvesting, 1 × 105 BMDCs were stained with fixable viability dye eFluor780 (eBioscience, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) and murine Alexa Fluor 488–labeled anti-CD11c antibodies (BioLegend, London, United Kingdom). To confirm the Fc-γ receptor–dependent mechanism of FVIII-IC binding, indicated samples with BMDCs were preincubated with purified rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2, BD Pharmingen) for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed and incubated with AF647-labeled FVIII-ICs generated with or without VWF. After a final washing step, BMDCs were analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) followed by data analysis with FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

In vitro model of the FVIII-specific recall response

The spleens from FVIII-immunized F8−/− mice were removed, and cells were prepared as described.22 The spleen cells contain FVIII-specific T and B cells.23 Cells were cultured at a density of 4 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) in prewarmed medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with GlutaMAX [Gibco, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany], 10% fetal bovine serum [Biochrom, Merck Millipore, Berlin, Germany], and 1% penicillin-streptomycin [Life Technologies]) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 6 days. RhFVIII (1 or 3 IU/mL Kogenate, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany,) with or without VWF (1 or 3 IU/mL) was added on day 1, as indicated. Cell culture supernatant was analyzed for cytokine containment by flow cytometry, and formation of FVIII-specific ASCs was detected by enzyme-linked immunospot assay, as described.22,23

In vivo model of the FVIII-specific recall response

Mice were housed in the animal housing facility at Hannover Medical School. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the German Welfare Act and approved by the regulatory authority. A colony of mice carrying a target disruption of exon 17 of the F8 gene (B6;129S4-F8tm2Kaz) was used in this study.24,25 Genotype was verified using DNA analysis from stool pellets.26 All mice were aged 10 ± 2 weeks at the start of experiments. For immunization, mice received 4 weekly intravenous doses of rhFVIII 80 IU/kg (Kogenate).

Splenocytes (1 × 107) from immunized F8−/− mice were filtered, washed, and injected intravenously into naïve F8−/− mice. On the next day, mice received intravenous rhFVIII (80 IU/kg Kogenate) and VWF (190 IU/kg), as indicated. The experiment was performed twice, with 3 or 4 mice per group as follows:

Group A: cells and rhFVIII (no VWF);

Group B: cells and rhFVIII together with VWF;

Group C: rhFVIII alone (no cells, no VWF);

Group D: cells only (no rhFVIII, no VWF); and

Group E: cells and VWF (no rhFVIII).

Anti-FVIII ELISA

Anti-FVIII IgG was determined by ELISA, as described.21 Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with rhFVIII (2 IU per well) and blocked with 5% BSA. Serially diluted serum samples (1:160 to 1:327 680) or control samples were incubated at RT for 2 hours, followed by washing, and detection with donkey anti-mouse IgG HRP. Titers were determined as the highest dilution of serum sample with an optical density of ≥0.3.

Bethesda assay

The Nijmegen-modified Bethesda assay was performed, as previously described.21 Briefly, serum obtained from group A and B from the in vivo model of the FVIII-specific recall response experiment was serially diluted (1:1 to 1:8192) using buffered human FVIII–deficient plasma (Siemens, Eschborn, Germany) and mixed with equal volume of standard human plasma (Siemens, Eschborn, Germany). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Residual FVIII activity was determined using a clotting assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Neutralizing potency of murine serum was determined on a lin/log regression curve, with a point of 50% inhibition being defined as 1 Bethesda unit (BU)/mL.

Inhibitory ratio was calculated as neutralizing antibodies (Bethesda titer)/binding antibodies (anti-FVIII total IgG titer) within each group.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc), Plotly Technologies Inc, and ggplot2 version 3.4.0. Groups were compared by one-way or two-way analysis of variance with Tukey or Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison, as appropriate (a detailed description can be found in corresponding figures legend). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (if not otherwise noted), and P values where statistical comparison was appropriate. The course of anti-FVIII titers in mouse experiments was evaluated using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing using ggplot2 version 3.4.0.

Results

FVIII-IC formation

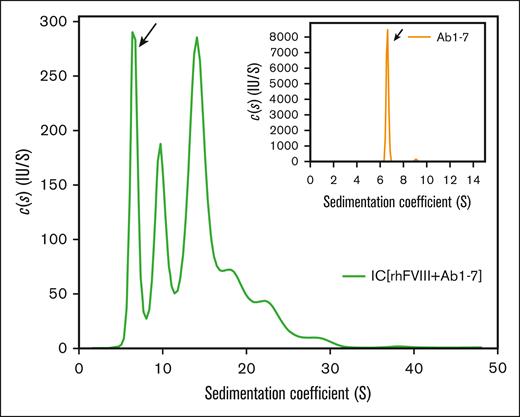

The formation of FVIII-ICs was studied using a set of well-defined, labeled anti-FVIII antibodies (Ab1-7). These antibodies target different epitopes in FVIII (Table 1) and have an inhibitory capacity of 5.5 BU per mL when used together at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. For analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) analysis, antibodies were used at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL (6.7 × 10−8 mol/L). Sedimentation velocity analysis with fluorescence detection confirmed that the main fraction of antibodies alone (>98%) was monomeric, and sedimented with 6.6 S corresponding to a molecular mass of 151 kDa (Figure 1, inset). After incubation with rhFVIII at an approximately equimolar ratio (20 μg/mL, 100 IU/mL, or 7.1 × 10−8 mol/L), complex formation was observed over a broad range of sizes, with sedimentation coefficients up to 30 S (Figure 1, main panel).

Sedimentation coefficient distribution of FVIII-containing immune complexes. FVIII-ICs were formed by incubation of a nearly equimolar ratio of rhFVIII (20 μg/mL or 7.1 × 10−8 mol/L) and AF488-labeled Ab1-7 (10 μg/mL or 6.7 × 10−8 mol/L, compare Table 1). Continuous c(s) distribution analysis of FVIII-IC was obtained from sedimentation velocity area under the curve with fluorescence detection. The free IgG fraction is marked by an arrow. The inset shows a sedimentation profile of labeled antibodies alone. Representative sedimentation coefficient distributions from 2 independent experiments are shown.

Sedimentation coefficient distribution of FVIII-containing immune complexes. FVIII-ICs were formed by incubation of a nearly equimolar ratio of rhFVIII (20 μg/mL or 7.1 × 10−8 mol/L) and AF488-labeled Ab1-7 (10 μg/mL or 6.7 × 10−8 mol/L, compare Table 1). Continuous c(s) distribution analysis of FVIII-IC was obtained from sedimentation velocity area under the curve with fluorescence detection. The free IgG fraction is marked by an arrow. The inset shows a sedimentation profile of labeled antibodies alone. Representative sedimentation coefficient distributions from 2 independent experiments are shown.

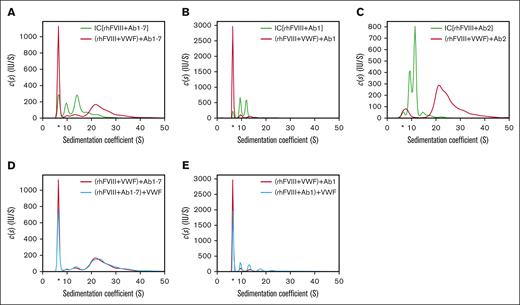

When rhFVIII was preincubated with VWF (100 international ristocetin cofactor units per mL [IU/mL]), FVIII-IC formation was reduced as indicated by the increased detection of free antibody (Figure 2A). However, the remaining FVIII-ICs that formed in the presence of VWF were significantly larger in size, indicating that VWF was incorporated into these FVIII-ICs.

Impact of VWF on FVIII-IC formation. Sedimentation coefficient distributions were obtained as described in Figure 1, with the exception that antibodies and VWF were used as follows: (A) rhFVIII and Ab1-7 (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1-7 (red trace); (B) rhFVIII with Ab1 only (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1 (red trace); (C) rhFVIII and Ab2 only (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab2 (red trace); (D) rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1-7 (red trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with Ab1-7 and then with VWF (blue trace); (E) rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1 (red trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with Ab1 and then with VWF (blue trace). The free IgG fraction is marked by an asterisk.

Impact of VWF on FVIII-IC formation. Sedimentation coefficient distributions were obtained as described in Figure 1, with the exception that antibodies and VWF were used as follows: (A) rhFVIII and Ab1-7 (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1-7 (red trace); (B) rhFVIII with Ab1 only (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1 (red trace); (C) rhFVIII and Ab2 only (green trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab2 (red trace); (D) rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1-7 (red trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with Ab1-7 and then with VWF (blue trace); (E) rhFVIII incubated first with VWF and then with Ab1 (red trace) compared with rhFVIII incubated first with Ab1 and then with VWF (blue trace). The free IgG fraction is marked by an asterisk.

Adding an unrelated plasma-derived protein, HSA, instead of VWF and applying a lower concentration of rhFVIII did not change the results (supplemental Figures 1 and 2, respectively).

Using Ab1 (anti-C1) alone, resulted primarily in FVIII-ICs of 2 different sizes, presumably corresponding to stoichiometric Ab to FVIII ratios of 1:1 and 1:2, and VWF prevented complex formation almost completely (Figure 2B).

Ab2 (anti-A2) alone also generated primarily 2 different FVIII-IC sizes. In the presence of VWF, however, complex formation was not prevented, but FVIII-IC shifted to larger sedimentation coefficients, indicating the incorporation of VWF (Figure 2C).

The incubation order of antibody and VWF did not affect FVIII-IC formation overall, only a small increase in the free IgG fraction was detected (Figure 2D). However, when using Ab1 alone, the previous incubation of rhFVIII with VWF prevented complex formation to a larger degree compared with the later addition of VWF (Figure 2E).

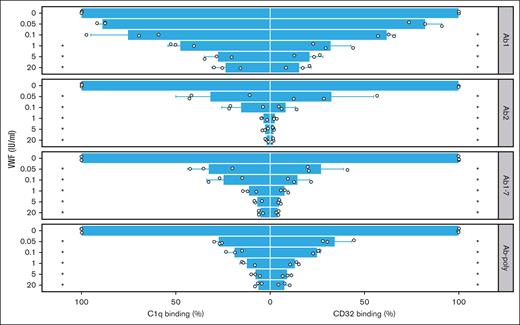

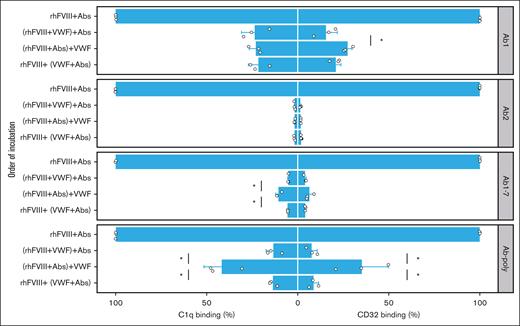

VWF inhibits functional properties of FVIII-IC

Next, we analyzed the impact of VWF on complement fixation of FVIII-ICs. When rhFVIII was preincubated with VWF before the addition of antibodies, binding of complement component C1q was suppressed in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3, left panels). Similar results were observed for Ab1 and Ab2 alone, indicating that VWF prevented C1q binding of antibodies irrespective of competition with its binding site. Likewise, VWF prevented C1q binding of Ab-poly from immunized mice (Figure 3, left part). These effects were observed over a broad range of VWF concentrations.

FVIII-IC binding to C1q and immobilized Fc-γ receptor is impaired by VWF. FVIII-IC were generated with rhFVIII (3 IU/mL or 2.1 × 10−9 mol/L) incubated first with VWF (0-20 IU/mL) and then with anti-FVIII antibodies (0.5 μg/mL or 3.3 × 10−9 mol/L). Binding to complement component C1q (left panels) and to CD32 (right panels) was assessed by ELISA. As a source of anti-FVIII Abs, either single anti-FVIII IgG Abs (Ab1 and Ab2), a combination (Ab1-7), or pooled serum from immunized F8−/− mice (Ab-poly) were used. Bar charts show the binding relative to FVIII-IC alone. The mean value ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent experiments done in duplicates is shown (individual data points are depicted). Statistical test was 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test with the Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance is displayed respectively for C1q and CD32 binding, showing the comparison with FVIII-IC alone; ∗P < .05.

FVIII-IC binding to C1q and immobilized Fc-γ receptor is impaired by VWF. FVIII-IC were generated with rhFVIII (3 IU/mL or 2.1 × 10−9 mol/L) incubated first with VWF (0-20 IU/mL) and then with anti-FVIII antibodies (0.5 μg/mL or 3.3 × 10−9 mol/L). Binding to complement component C1q (left panels) and to CD32 (right panels) was assessed by ELISA. As a source of anti-FVIII Abs, either single anti-FVIII IgG Abs (Ab1 and Ab2), a combination (Ab1-7), or pooled serum from immunized F8−/− mice (Ab-poly) were used. Bar charts show the binding relative to FVIII-IC alone. The mean value ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent experiments done in duplicates is shown (individual data points are depicted). Statistical test was 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test with the Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance is displayed respectively for C1q and CD32 binding, showing the comparison with FVIII-IC alone; ∗P < .05.

Identical results were obtained with the immobilized CD32, the model for Fc receptor binding of FVIII-IC (Figure 3, right panels). When rhFVIII was preincubated with increasing amounts of VWF, CD32 binding of FVIII-IC was increasingly prevented irrespectively of antibody used.

The order of incubation was important for the prevention of C1q binding when using Ab1-7 together, or Ab-poly, with incomplete suppression observed when antibodies were allowed to bind to rhFVIII before VWF was added (Figure 4, left panels).

Effect of incubation order of rhFVIII, antibodies, and VWF on the prevention of C1q and CD32 binding. Binding to complement component C1q (left panels) and to CD32 (right panels) of rhFVIII (3 IU/mL), antibodies (0.5 μg/mL), and VWF (20 IU/mL) incubated in the indicated order was assessed by ELISA. As a source of anti-FVIII antibodies, either single anti-FVIII IgG Abs (Ab1 and Ab2), a combination (Ab1-7), or pooled serum from immunized F8−/− mice (Ab-poly) were used. Bar charts show the binding relative to FVIII-IC alone. The mean value ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in duplicates is shown (individual data point are depicted). Comparison between groups with VWF addition was performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by HSD test with the Bonferroni correction (only significant differences are shown; ∗P < .05).

Effect of incubation order of rhFVIII, antibodies, and VWF on the prevention of C1q and CD32 binding. Binding to complement component C1q (left panels) and to CD32 (right panels) of rhFVIII (3 IU/mL), antibodies (0.5 μg/mL), and VWF (20 IU/mL) incubated in the indicated order was assessed by ELISA. As a source of anti-FVIII antibodies, either single anti-FVIII IgG Abs (Ab1 and Ab2), a combination (Ab1-7), or pooled serum from immunized F8−/− mice (Ab-poly) were used. Bar charts show the binding relative to FVIII-IC alone. The mean value ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in duplicates is shown (individual data point are depicted). Comparison between groups with VWF addition was performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by HSD test with the Bonferroni correction (only significant differences are shown; ∗P < .05).

Analogous to C1q binding, the addition of VWF to preformed FVIII-ICs using Ab-poly only suppressed CD32 binding to a limited extent (Figure 4, right panels). Of note, substituting VWF for HSA in both C1q and CD32 ELISA did not influence FVIII-IC binding, confirming that the impact is VWF-specific (supplemental Figure 3).

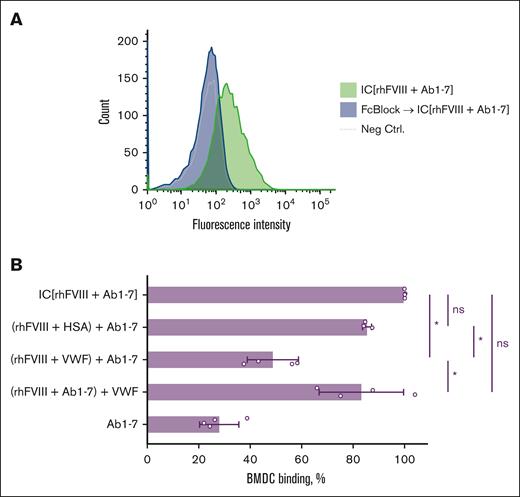

We were also interested in determining whether the D'D3 fragment of VWF alone is sufficient to impair C1q and CD32 binding. It was demonstrated that although the D'D3 dimer could inhibit the binding of FVIII-ICs to the effector molecules, the entire VWF was more efficient (supplemental Figure 4). Furthermore, the binding of FVIII-IC to BMDC, that express both high- and low-affinity Fc receptors on their surface,15 was analyzed. We could confirm the Fc-γ receptor–dependent mechanism of the FVIII-IC binding to BMDCs (Figure 5A). FVIII-IC binding was demonstrated to partially be prevented by VWF when it was preincubated with FVIII (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 5). This effect was VWF-specific as demonstrated by using HSA instead of VWF (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 5). VWF also partially inhibited the BMDC binding of FVIII-IC formed with Ab-poly (supplemental Figure 6).

VWF impairs FVIII-IC binding to Fc-γ receptor on APCs. (A) Representative flow cytometry histograms of FVIII-IC binding to murine BMDC, confirming the Fc-γ receptor–dependent binding mechanism. FVIII-ICs were generated by mixing of 7 AF647-labeled monoclonal anti-FVIII antibodies (Ab1-7; refer to Table 1) and rhFVIII. BMDCs without staining served as negative control (Neg Ctrl.). (B) Normalized binding of FVIII-ICs to BMDCs. Preincubated molecules are indicated by round parentheses. The data represent the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the respective sample divided by the MFI of IC (rhFVIII + Ab1-7), multiplied by 100. The mean values ± SD obtained from 4 independent experiments done in duplicates are shown. For the (rhFVIII + HSA) + Ab1-7 sample, 3 independent experiments were performed in duplicates. The statistical comparison was made using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance: ∗P < .05. ns, not significant.

VWF impairs FVIII-IC binding to Fc-γ receptor on APCs. (A) Representative flow cytometry histograms of FVIII-IC binding to murine BMDC, confirming the Fc-γ receptor–dependent binding mechanism. FVIII-ICs were generated by mixing of 7 AF647-labeled monoclonal anti-FVIII antibodies (Ab1-7; refer to Table 1) and rhFVIII. BMDCs without staining served as negative control (Neg Ctrl.). (B) Normalized binding of FVIII-ICs to BMDCs. Preincubated molecules are indicated by round parentheses. The data represent the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the respective sample divided by the MFI of IC (rhFVIII + Ab1-7), multiplied by 100. The mean values ± SD obtained from 4 independent experiments done in duplicates are shown. For the (rhFVIII + HSA) + Ab1-7 sample, 3 independent experiments were performed in duplicates. The statistical comparison was made using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance: ∗P < .05. ns, not significant.

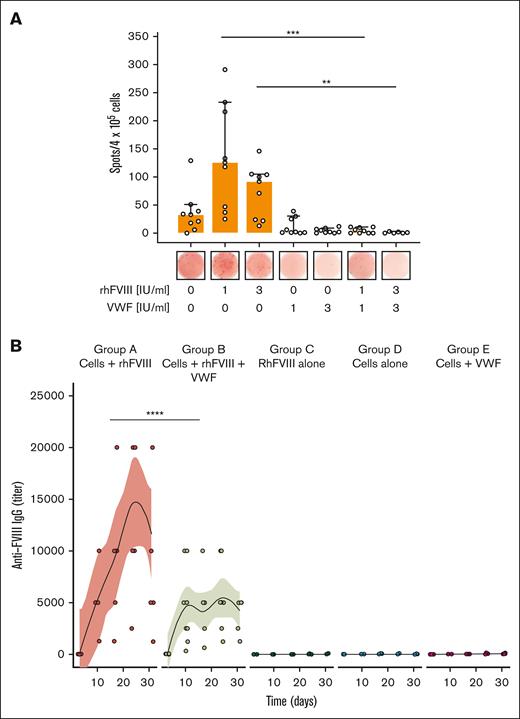

Impact of VWF in mouse models of the FVIII-specific recall response

The de novo formation of FVIII-specific ASCs is an established in vitro model of the FVIII-specific recall response. Splenocytes from previously FVIII-sensitized F8−/− mice formed FVIII-specific ASCs when rechallenged with rhFVIII in vitro (Figure 6A). ASC formation was partially suppressed with high doses of rhFVIII, as previously described.21,23 Adding VWF to rhFVIII abolished ASC formation. It also suppressed the formation of the major T-cell cytokines interferon gamma and interleukin-10 (Table 2).

VWF suppresses FVIII-specific recall response in vitro and in vivo. (A) Model of FVIII-specific recall response in vitro. Splenocytes obtained from immunized F8−/− mice were stimulated with rhFVIII in the presence or absence of VWF for 6 days. FVIII-specific ASCs were detected by enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Three independent experiments done in duplicates are shown. Median and 95% confidence intervals as well as individual biological points are shown. One-way ANOVA on ranks (Kruskal-Wallis test) with Dunn multiple comparisons test was performed. (B) FVIII-specific recall response in vivo. Adoptive transfer of primed splenocytes into naïve F8−/− mice, followed by exposure to rhFVIII with or without VWF. The anti-FVIII IgG titer was quantified at indicated time points by ELISA. Individual data points for each mouse are shown (jittered by a factor 0.8 to prevent over plotting). The curves and shaded areas are mean and 95% confidence intervals of polynomial regression. Groups were compared by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance: ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

VWF suppresses FVIII-specific recall response in vitro and in vivo. (A) Model of FVIII-specific recall response in vitro. Splenocytes obtained from immunized F8−/− mice were stimulated with rhFVIII in the presence or absence of VWF for 6 days. FVIII-specific ASCs were detected by enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Three independent experiments done in duplicates are shown. Median and 95% confidence intervals as well as individual biological points are shown. One-way ANOVA on ranks (Kruskal-Wallis test) with Dunn multiple comparisons test was performed. (B) FVIII-specific recall response in vivo. Adoptive transfer of primed splenocytes into naïve F8−/− mice, followed by exposure to rhFVIII with or without VWF. The anti-FVIII IgG titer was quantified at indicated time points by ELISA. Individual data points for each mouse are shown (jittered by a factor 0.8 to prevent over plotting). The curves and shaded areas are mean and 95% confidence intervals of polynomial regression. Groups were compared by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance: ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Adoptive transfer of splenocytes from immunized F8−/− mice to naïve F8−/− mice was used as an in vivo model of the FVIII-specific recall response. The injection of a single intravenous dose of rhFVIII resulted in rapid formation of anti-FVIII antibodies (Figure 6B, group A) that was not observed when either cells or rhFVIII were not administered (Figure 6B, groups C and D). When rhFVIII was incubated with VWF before injection, anti-FVIII antibody formation was significantly suppressed and no increase after day 10 was observed (Figure 6B, group B).

In addition, preincubation of rhFVIII with VWF before infusion reduced the formation of neutralizing anti-FVIII antibodies (supplemental Figure 7A). Of note, the inhibitory fraction of the formed anti-FVIII antibodies remained unchanged in mice that received either only rhFVIII or rhFVIII + VWF (supplemental Figure 7B).

Discussion

The immune response against FVIII in persons with hemophilia A is believed to occur along the classical steps of an adaptive immune response to external, foreign antigen.8 Much has been learned about the impact of VWF on the initial uptake of FVIII antigen into APCs, and its immunoprotective impact on the primary immune response.27-33

Our experiments suggest that VWF also modulates important aspects of the secondary immune response, when anti-FVIII antibodies are already abundant and FVIII treatment is continued, for example, in the setting of ITI.

An effect of VWF on the binding of inhibitors to FVIII was negligible for most antibodies in our experiments. Only for Ab1 alone, whose epitope directly competes with the main VWF binding site,6,34 we were able to show that VWF prevented FVIII-IC formation. VWF did not prevent FVIII-IC formation with an antibody directed to an epitope distant from its binding site, nor with the combination of antibodies Ab1-7. However, VWF was still efficient in preventing C1q and Fc receptor binding of those antibodies. This was confirmed with polyclonal anti-FVIII from immunized F8−/− mice. VWF also reduced FVIII-IC binding to BMDCs. One possible explanation for the lower binding detection could be the following: in the presence of VWF, fewer IgG molecules are incorporated into the FVIII-IC, resulting in a decrease in fluorescence intensity. Moreover, the production of T-cell cytokines interferon gamma and interleukin-10 was decreased, de novo generation of FVIII-specific ASCs was abolished, and the in vivo recall response in mice receiving primed splenocytes was significantly dampened.

These results suggest that VWF modulates effector functions of anti-FVIII antibodies, even if it does not prevent their binding, immune complex formation, and FVIII functional neutralization. VWF is a large multidomain glycoprotein of 500 to 20 000 kDa, several-fold larger than FVIII (280 kDa) and IgG (150 kDa). It is reasonable to assume that incorporation of VWF into FVIII-IC could shield, at least in part, the Fc portions of antibodies and thereby prevent some of their effector functions. This hypothesis is consistent with the experimental data because it was observed that when only the D’D3 fragment of the VWF was tested, it exhibited partial prevention of FVIII-IC binding to the effector molecules. However, further investigation is required to confirm our hypothesis, necessitating the use of more sophisticated techniques such as imaging flow cytometry.

According to this interpretation of our data, VWF would neutralize, in part, the effects that antibodies have as “natural adjuvants” during a secondary immune response.14 Hartholt et al showed that BMDCs were threefold to fourfold more efficient in the binding of FVIII-IC as compared with similar concentrations of FVIII alone.15 Our experiments demonstrate that this can be prevented by the addition of VWF.

Not much is known about the role of complement in the immune response against FVIII. Rayes et al showed that complement C3b enhanced the binding of rhFVIII to monocyte-derived dendritic cells.35 In their experiments, complement depletion of F8−/− mice reduced the primary immune response against rhFVIII but did not decrease antibody titers when mice were already sensitized. Whether complement activation by FVIII-IC plays a role in uptake of FVIII into APCs and whether VWF can possibly prevent it, is unclear.

Chen et al were the first to demonstrate that VWF diminished the proliferation of FVIII-sensitized CD4+ T cells and ASCs in vitro, as well as anti-FVIII titers in an adoptive cell transfer model using immunocompromised mice.36 We extended this work by transfusing sensitized splenocytes into immunocompetent F8−/− mice, and still observed a largely reduced recall response when VWF was added to rhFVIII. We had previously used a similar model to show that inhibition or deletion of Fc-γ receptors abolished formation of FVIII-specific ASCs.20,21 Taken together, these data indicate that Fc receptor interaction plays an important role in the secondary immune response to FVIII and that this can be prevented by Fc receptor inhibition or “protection” of FVIII by VWF. It is worth mentioning that the results obtained from in vivo experiments should not be directly extrapolated to humans, because the presence of the antigenic competition phenomenon cannot be ruled out.37 Although the injected splenocytes were exclusively primed against human FVIII and are unlikely to be subject to competition with naïve B-cells reacting with human VWF, it would still be ideal to use pure and functional murine VWF. However, the current availability of such resources is limited. Although our data suggest that VWF modulates the effector functions of FVIII-IC, the fate of these immune complexes in the body remains unclear. Further work is required to show how VWF can alter the deposition, clearance, and antigen presentation of FVIII-IC in vivo.

Further work is also required to demonstrate why intrinsic VWF would not be sufficient to exert the protective effects suggested by our data. The affinity to FVIII is similar for VWF and typical anti-FVIII antibodies with KD values of ∼2 × 10−10 M.38,39 This suggests that not all FVIII molecules can bind VWF in the presence of antibodies that compete for its binding site. Furthermore, VWF binding may be affected by posttranslational modification, and not all rhFVIII may bind equally well to VWF.9 Using rhFVIII of the third generation (octocog-α) and a noncommercial, FVIII-free plasma–derived VWF preparation, we found that preincubation was significantly more effective than later addition of VWF in preventing C1q and Fc receptor binding. Of note, the difference seen in the secondary immune response in vivo was against a background of murine VWF present in these mice.

Preclinical studies do not always translate into findings in humans. A systematic review and meta-analysis did not observe higher rates of ITI success in patients treated with VWF-containing products compared with those treated with FVIII concentrates devoid of VWF.13 However, the authors identified a high risk of bias caused by inclusion of more patients who were at high risk in the VWF-containing concentrate group. Noncontrolled studies suggested high rates of ITI success with VWF-containing concentrates in patients with poor risk factors.40-44 Patient characteristics, most clearly the peak inhibitor titer, are major determinants of ITI success in the clinic.5 A randomized study would be needed to demonstrate the effect of product characteristics, including the content of VWF.

In summary, our in vitro and in vivo data demonstrate that addition of VWF to rhFVIII does not prevent FVIII-IC formation but attenuates effector functions of immune complexes and the secondary anti-FVIII recall response in immunocompetent mice. VWF-containing factor concentrates could be beneficial for ITI and should be further explored in clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lidia Litz and Annika Klingberg for excellent technical assistance, and Jan Faix for providing enhanced green fluorescent protein–Cofilin as a control protein.

This project was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany.

The renewal of the fluorescence detection system of the analytical ultracentrifuge was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation), INST 192/534-1 FUGG.

Authorship

Contribution: O.O. and A.T. wrote the manuscript; S.W. supervised the project; and all authors designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, revised the manuscript, and approved the manuscript's final content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: O.O. reports grants for research from Biotest and Octapharma. A.T. reports grants for studies and research from Bayer, Biotest, Chugai/Roche, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, and Takeda, and personal fees for lectures or consultancy from Bayer, Biotest, Chugai/Roche, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB, and Takeda. S.W. reports grants for research from Biotest and Octapharma, and honoraria for lectures or consultancy from Biotest and Stago. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sonja Werwitzke, Department of Hematology, Hemostasis, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation, Hannover Medical School, Carl Neuberg Str 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany; e-mail: werwitzke.sonja@mh-hannover.de.

References

Author notes

Data contained in this article are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Sonja Werwitzke (werwitzke.sonja@mh-hannover.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.