TO THE EDITOR:

Event-free survival in children, adolescents, and young adults (CAYAs) with newly diagnosed B-cell lymphoma (BCL) exceeds 80% with multimodal therapy.1-3 However, overall survival (OS) plummets to 30% in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) disease despite chemoimmunotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).4 Novel salvage approaches are critically needed.

Tisagenlecleucel (KYMRIAH, Novartis), a CD19–directed chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CART), is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients aged ≤25 years with R/R B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and in adults with R/R diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma.5 Tisagenlecleucel affords outcomes superior to historical regimens in adults with R/R DLBCL,6-9 although alternative CART constructs may offer superior efficacy in this population.10,11 Three additional CART products are FDA approved for R/R BCL in adults (axicabtagene ciloleucel, brexucabtagene autoleucel, and lisocabtagene maraleucel); however, none are approved for pediatric BCL.12 In addition to DLBCL, BCL in CAYAs also include B-lymphoblastic lymphoma (B-LLy), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), for which tisagenlecleucel is not FDA approved in adults, and data to support its use in these diseases are scarce. Experience is very limited with tisagenlecleucel in CAYAs with R/R BCL, although this is the subject of the phase 2 BIANCA trial (NCT03610724).13 Here, we describe real-world use of tisagenlecleucel in CAYAs with R/R BCL.

We surveyed 48 sites in the Pediatric Real-World CAR Consortium to retrospectively analyze outcomes using commercial tisagenlecleucel in CAYAs with R/R BCL. Eligible patients had R/R BCL, were aged ≤25 years at the time of tisagenlecleucel infusion, did not receive tisagenlecleucel on a clinical trial, and were ≥28 days after CART by 24 July 2023. Response was determined by treating physician based on a combination of positron emission tomography/computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, bone marrow evaluation, and/or cerebrospinal fluid studies.14 Overall response rate (ORR) was the sum of patients with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) divided by the total number of patients infused with tisagenlecleucel. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity were retrospectively graded per American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy guidelines based on available clinical data.15 Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from tisagenlecleucel until relapse, progression, or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from tisagenlecleucel until death from any cause. Survival analyses used Kaplan-Meier with log-rank test for comparison between groups using R version 4.3.1 (Vienna, Austria). Each center obtained necessary review and approvals from their local institutional review boards before data entry.

Patient characteristics and tisagenlecleucel responses are reported in Table 1. Thirteen patients with R/R BCL received tisagenlecleucel between 2019 and 2023 at 9 centers. The median age at infusion was 20 years (range, 7-24). Six patients (46%) had B-LLy, 2 (15%) had BL, 2 (15%) had PTLD DLBCL (Epstein-Barr virus positive, n = 1; Epstein-Barr virus negative, n = 1), 2 had primary mediastinal BCL, and 1 had non-PTLD DLBCL. Seven patients (54%) had primary refractory disease, and 6 (46%) were in second or greater relapse. Three (23%) had received prior allogeneic HSCT. Three patients (23%) had central nervous system involvement at the time of CART. All patients received lymphodepletion with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide (n = 11 [85%]) or bendamustine (n = 2 [15%]). Median CART dose was 3.4 × 106 cells per kg (range, 1.2 × 106 to 9.5 × 106). One patient with B-LLy received an out-of-specification product due to product viability of 78%.

Of patients with PTLD, 1 had undergone renal transplant (13 years prior), and 1 had undergone heart transplant (17 years prior). One patient had tacrolimus held for 2 weeks before leukapheresis and 2 weeks before CART, with tacrolimus resumption on day 1 after CART (trough, 5-8 ng/mL); prednisone was permanently discontinued 2 weeks before leukapheresis. The other patient with PTLD continued tacrolimus throughout leukapheresis and CART (trough, 3-8 ng/mL).

Ten patients (77%) had CRS, 2 (15%) of whom had grade 3 CRS; none experienced grade ≥4 CRS. Median time to CRS from CART infusion was 3 days (range, 1-7). Median CRS duration was 5.5 days (range, 2-13). Three patients (23%) received tocilizumab, 2 of whom also received steroids. One patient (8%) experienced neurotoxicity (grade 3, n = 1); notably, this patient had central nervous system disease at CART. Ten (77%) developed absolute neutrophil count <0.5 x 103/μL (median time to recovery, 10 days [range, 2-19]). Median time to absolute lymphocyte recovery >0.2 x 103/μL was 6 days (range, 3-26). Evaluable data on B-cell recovery were limited. Further study on the clinical relevance of post-CART B-cell aplasia in CAYAs with BCL is warranted.

Median inpatient length of stay was 14 days (range, 5-19). Four patients required intensive care unit admission, with median length of stay of 2.5 days (range, 1-10). One patient with a history of chronic graft-versus-host disease involving eyes, liver, lungs, mouth, and skin, which had clinically resolved before CART, developed extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease after CART by Seattle criteria of prior involved organ systems in addition to genital tract and joints/fascia. Neither patient with PTLD experienced allograft rejection after CART. There were no treatment-related deaths or tumor lysis syndrome.

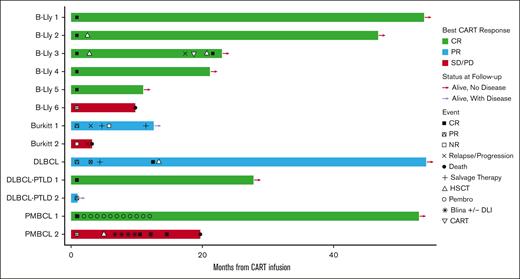

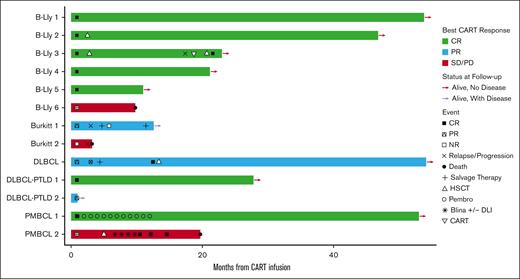

Response and follow-up data are in Table 1 and Figure 1. ORR was 10 of 13 (77%), including 7 (54%) CR and 3 (23%) PR. Among patients with B-LLy (n = 6), 5 (83%) had CR, and 1 (17%) had stable disease. Two of these patients underwent preemptive allogeneic HSCT while in CART-mediated CR with B-cell aplasia. Among patients with mature BCL (n = 7), ORR was 71%, with 2 achieving CR (29%). Divided by mature BCL subtype, ORR was 50% for BL (PR, 1/2), 100% for DLBCL (CR, 1/3; PR, 2/3), and 50% for primary mediastinal BCL (CR, 1/2).

Swimmer plot of clinical courses after tisagenlecleucel in pediatric and young adult patients with R/R BCL. Blina, blinatumomab; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; PD, progressive disease; Pembro, pembrolizumab; PMBCL, primary mediastinal BCL; SD, stable disease.

Swimmer plot of clinical courses after tisagenlecleucel in pediatric and young adult patients with R/R BCL. Blina, blinatumomab; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; PD, progressive disease; Pembro, pembrolizumab; PMBCL, primary mediastinal BCL; SD, stable disease.

Of 7 patients with CR, 1 (17%) with B-LLy relapsed with CD19+ disease 17 months after CART infusion and 15 months after preemptive HSCT. This patient was salvaged with investigational CART therapy and HSCT. Two of 3 patients with PR (BL, n = 1; non-PTLD DLBCL, n = 1) subsequently relapsed with CD19– disease, 1 of whom achieved CR with immunochemotherapy and HSCT. The third patient with PR (PTLD DLBCL) was 1 month from CART at data cutoff, and his/her subsequent course is unknown. Four patients (57%) with CR (B-LLy, n = 3; PTLD DLBCL, n = 1) remain in CR without additional therapies after CART.

At median follow-up of 21 months (range, 0.9-54), 8 patients (62%) are alive without disease, 2 (15%) are alive with disease, and 3 (23%) are deceased. The estimated post-CART 12-month PFS and OS were 59% and 83%, respectively (supplemental Figures 1 and 2). CART-mediated CR was associated with significantly improved PFS (P < .001) and OS (P = .015).

In this small, heterogenous cohort, tisagenlecleucel was tolerable, safe, and active in subsets of CAYAs with R/R BCL. B-LLy is considered biologically similar to B-ALL and is treated using the same protocols.16 Concordantly, among patients with B-LLy, a CR rate of 83% is consistent with CART clinical trial and real-world reporting for R/R B-ALL.8,17,18 Among patients with mature BCL, the CR rate was lower at 29%, and ORR was 71%, which resembles the adult tisagenlecleucel R/R BCL experience.7,8 Preliminary BIANCA results demonstrated a 32% ORR, with inferior responses in patients with BL vs LBCL (20% vs 46%, respectively).13 Of note, BIANCA included only patients with BL or LBCL and excluded PTLD. The rates of CRS and neurotoxicity in this cohort were similar to those in BIANCA and were modest in severity (all grade ≤3).13 Notably, no nonresponders (n = 3) are alive at follow-up, which is consistent with adult data showing that CART refractoriness portends a poor prognosis in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.19 Whether this is due to underlying lymphoma biology or the heavily pretreated nature of these nonresponding patients cannot be answered in this small cohort.

This cohort includes, to our knowledge, the first report of tisagenlecleucel in a pediatric patient with PTLD. The use of CART for PTLD and the management of immunosuppression around CART remain challenging, given the need to prevent allograft rejection while optimizing T-cell function at leukapheresis and CART persistence. In a large retrospective cohort, adults with PTLD treated with CD19-directed CART showed a 64% ORR, similar to pivotal trials for non-PTLD BCL, although 14% of patients experienced allograft rejection after CART.20 Given the limited experience with CART in PTLD, it is unknown how age, disease, and type of CD19 CART used (CD28 vs 41BB costimulation) may influence outcomes. In our cohort, both patients with PTLD responded to CART (CR, n = 1; PR, n = 1), with similar toxicities to patients without PTLD. Although post-CART tacrolimus seemingly did not affect outcomes, the type and degree of immunosuppression used after CART remain understudied.

Despite the limitations of a small and heterogeneous cohort, short follow-up, and noncentral response assessments, this report suggests that tisagenlecleucel may be safe and efficacious in CAYAs with R/R BCL, a population with limited salvage options. Mature data from the recently completed BIANCA trial will further inform the use of tisagenlecleucel in these patients; however, further study of CART in CAYAs with R/R PTLD is needed, given this population’s special clinical considerations.

Contribution: J.D.B., S.D., C.M.C., A.M., K.T., A.V., J.-A.T., C.B., L.M.S., and L.P. designed the study; J.D.B. and L.P. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and all authors assisted in data collection and interpretation of the data, along with reviewing and revising the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.M.C. reports honoraria for advisory board membership from Bayer, Elephas, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, and WiCell Research Institute. T.C.Q. reports speaker’s bureau for Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. L.M.S. served on advisory boards for Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Cargo Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonathan D. Bender, Cancer and Blood Diseases Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, MLC 7018, Cincinnati, OH, 45229-3026; email: jonathan.bender@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

L.M.S. and L.P. are joint senior authors.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to the corresponding author, Jonathan D. Bender (jonathan.bender@cchmc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.