Key Points

High-dose alemtuzumab led to effective suppression of cGVHD.

Lymphodepletion delays naive T cell (Tn) recovery resulting in lower T-cell receptor repertoire and higher Treg:Tn ratio.

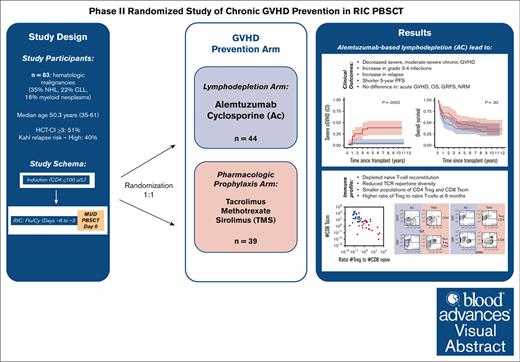

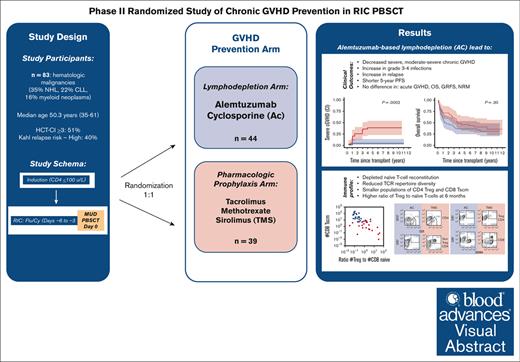

Visual Abstract

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) remains a significant problem for patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Although in vivo lymphodepletion for cGVHD prophylaxis has been explored in the myeloablative setting, its effects after reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) are not well described. Patients (N = 83) with hematologic malignancies underwent targeted lymphodepletion chemotherapy followed by a RIC allo-HSCT using peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors. Patients were randomized to 2 GVHD prophylaxis arms: alemtuzumab and cyclosporine (AC; n = 44) or tacrolimus, methotrexate, and sirolimus (TMS; n = 39), with the primary end point of cumulative incidence of severe cGVHD. The incidence of severe cGVHD was lower with AC vs TMS prophylaxis at 1- and 5-years (0% vs 10.3% and 4.5% vs 28.5%; overall, P = .0002), as well as any grade (P = .003) and moderate-severe (P < .0001) cGVHD. AC was associated with higher rates of grade 3 to 4 infections (P = .02) and relapse (52% vs 21%; P = .003) with no difference in 5-year GVHD-free-, relapse-free-, or overall survival. AC severely depleted naïve T-cell reconstitution, resulting in reduced T-cell receptor repertoire diversity, smaller populations of CD4Treg and CD8Tscm, but a higher ratio of Treg to naïve T-cells at 6 months. In summary, an alemtuzumab-based regimen successfully reduced the rate and severity of cGVHD after RIC allo-HSCT and resulted in a distinct immunomodulatory profile, which may have reduced cGVHD incidence and severity. However, increased infections and relapse resulted in a lack of survival benefit after long-term follow-up. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT00520130.

Introduction

For patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) can be a curative therapy, mediated through immunological graft-versus-tumor effects. Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is an important late complication of transplant and a major cause of nonrelapse morbidity, mortality, and chronic disability, also associated with fewer malignancy relapses.1 Because current systemic treatments for patients with cGVHD are unsatisfactory, developing effective prevention strategies are of major interest.2,3 Patients with severe forms of cGVHD4 are those who bear the highest mortality and functional disability and should be the primary target for prevention. Therefore, a better understanding of the in vivo immunobiology associated with the development of clinical cGVHD is an important clinical research goal.

Methods for pharmacological prevention of GVHD are based on combinations of a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) plus another agent, most commonly low-dose methotrexate, or use of high-dose post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy).5 With the recognized role of donor T cells in GVHD, many studies of GVHD prevention focus on either in vivo depletion of donor T cells by systemic administration of polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies (antithymocyte globulin [ATG] and anti-CD52, alemtuzumab, respectively)6-12 or PT-Cy13-15; or ex vivo graft manipulation via CD34+ selection16-19 or αβ T-cell depletion.20,21 Antibodies such as ATG and alemtuzumab exert variable effects based on dosage, timing of administration, and formulation.22-27 Early studies used high doses of alemtuzumab (a total dose of 100 mg).28,29 However, in today’s treatment landscape, safe de-escalation to total doses ranging between 30 to 60 mg is achievable without compromising clinical outcomes.30,31 Although higher doses have a strong protective effect against GVHD,7,8,32-34 this often comes with increased rates of relapse, graft rejection, infections,35,36 and Epstein-Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative disease.37 Furthermore, timing alemtuzumab dosing during conditioning, proximally or distally, can affect outcomes such as achievement of full donor chimerism, relapse, and GVHD.38

Benefits of in vivo lymphodepletion, including the reduction in incidence of both acute GVHD (aGVHD) and cGVHD for allo-HSCT with myeloablative conditioning using matched unrelated donors (MUD) have been well established through several large, randomized controlled trials using ATG.7,8,10,39 However, older patients cannot tolerate myeloablative conditioning due to frailty or comorbidity and undergo transplants with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens in which efficacy is primarily dependent on graft-versus-tumor effects from the functional lymphocytes infused within the graft. Additionally, the risk of cGVHD is increased with older recipient age, transplantation from unrelated donors, and the use of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) source; the latter 2 of which are the predominant stem cell source of RIC allografts for allo-HSCT,40 emphasizing the need for improved understanding and development of cGVHD prevention strategies in the RIC setting. Although the introduction of PT-Cy is adopted as the standard for haploidentical (haplo) allo-HSCT, it is also moving to the forefront of cGVHD prevention for RIC allo-HSCT using fully matched donors due to recently presented randomized data41 that showed effective decrease in cGVHD and improved GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS). Though this did not translate into a difference in overall survival (OS), and long-term effects on organ toxicity, infections, and relapse are yet to be seen. Therefore, exploring alternative approaches for cGVHD prevention and elucidating the immunological mechanisms driving the development of cGVHD, or lack thereof, remains an important goal for the field.

In this randomized, single-center, open-label, phase 2 prospective trial, we directly compared the clinical and immunological consequences of 2 strategies to prevent GVHD: post-HSCT in vivo depletion of donor lymphocytes using high-dose alemtuzumab28,42 vs pharmacological suppression43 of immune activation in the setting of reduced-intensity PBSC transplants. We further describe novel immunobiological changes associated with post-HSCT immune reconstitution in the context of these 2 approaches, as well as that associated with the development of cGVHD in this prospective, randomized setting.

Methods

Study details

Patients were enrolled between September 2007 and May 2014. Details on eligibility criteria and donor selection are reported in the supplemental Method.

Study design

Patients first received disease-specific induction chemotherapy cycles (range, 1-3 cycles)44,45 for host lymphodepletion aiming for an absolute CD4+ T-cell target <0.1 x 103/µL before transplant to accelerate the achievement of full donor chimerism46,47 (supplemental Method; supplemental Figure 1). All patients received an identical conditioning regimen consisting of concurrent fludarabine (30 mg/m2 per day for 4 days) and cyclophosphamide (1200 mg/m2 per day for 4 days),47 followed by infusion of a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized T-cell replete peripheral blood allograft from an HLA-matched or -mismatched unrelated donor procured via the National Marrow Donor Program. Patients with hematologic malignancy were randomly assigned to receive either of the following 2 GVHD prophylaxis regimens: (1) high-dose alemtuzumab and cyclosporine (AC)28,42; or (2) tacrolimus, sirolimus, and methotrexate (TMS).43 The primary objective was to determine the cumulative incidence of severe cGVHD per National Institutes of Health (NIH) global severity score in the 2 arms.48 Secondary objectives were to determine the incidence, organ severity, and overall severity of cGVHD48 and aGVHD (grades 2-4 and 3-4).49 Statistical methods, end points, and immunological correlate analyses are described in the supplemental Method.

Treatment arms

TMS arm

Tacrolimus was initiated on day –3 before stem cell infusion, administered by continuous IV infusion at a dose of 0.02 mg/kg per day with a target serum level of 5 to 10 ng/mL, and converted to an equivalent oral dose given every 12 hours before discharge. Sirolimus was initiated on day –3, administered by mouth with an initial loading dose of 12 mg, and subsequently, 4 mg by mouth each day, with goal trough levels of 3 to 12 ng/mL. Both were continued and reduced by one-third at days +63, +119 (± 2 days), and then completely discontinued by day +182 (6 months) if there were no signs of GVHD. Methotrexate 5 mg/m2 IV was given over 15 minutes on days +1, +3, +6, and +11.

AC arm

Alemtuzumab (CAMPATH-1H, humanized monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody) was administered at 20 mg per day by IV infusion over 8 hours on days −8 to −4 (total dose of 100 mg, defined as high-dose alemtuzumab throughout this manuscript) with premedication per standard of care. Cyclosporine (CsA) was initiated on day –1 before HSCT and administered by IV infusion at 2 mg/kg per dose every 12 hours, with target serum range of 175 to 250 μg/mL. CsA was converted to an equivalent oral dose given every 12 hours and continued until day +100 and then was tapered as long as the severity of GVHD was grade ≤2. CsA was tapered by reducing the dose by ∼10% from the last dose administered each week to a dose of 25 mg per day and completely discontinued by 6 months after HSCT if there were no signs of GVHD.

The study protocol was approved by the National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board, and all patients signed an informed consent to participate (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00520130).

Results

Patient characteristics

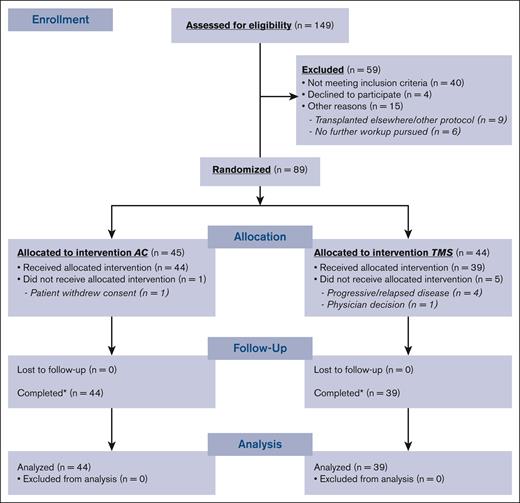

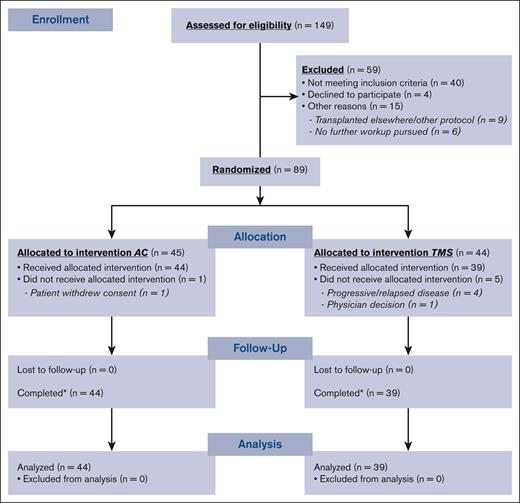

Ninety-two patients were enrolled, 89 patients were randomized, and 83 (AC, n = 44; TMS, n = 39) ultimately underwent transplantation (Figure 1). Patient and disease characteristics among both arms were similar, except for a higher number of prior therapies (P = .016) and higher CD34+ cells per kg infused dose in the AC arm (P = .034; Table 1).

Engraftment and hematologic recovery

Median time to neutrophil recovery was shorter in the AC than in the TMS arm (9 days [range, 7-36] vs 11 days [range, 3-19]; P = .02); time to platelet recovery52 was similar (14 days [range, 1-431] vs 19 days [range, 1-99]; P = .96). In the AC arm, primary graft failure52 occurred in 2 patients (1 with myeloma and 1 with myelofibrosis), with the former patient successfully undergoing engraftment after a second transplant. High donor chimerism (>95%) was achieved early on days +14 and +28 after transplant and were similar in both arms (supplemental Figure 2).

aGVHD and cGVHD

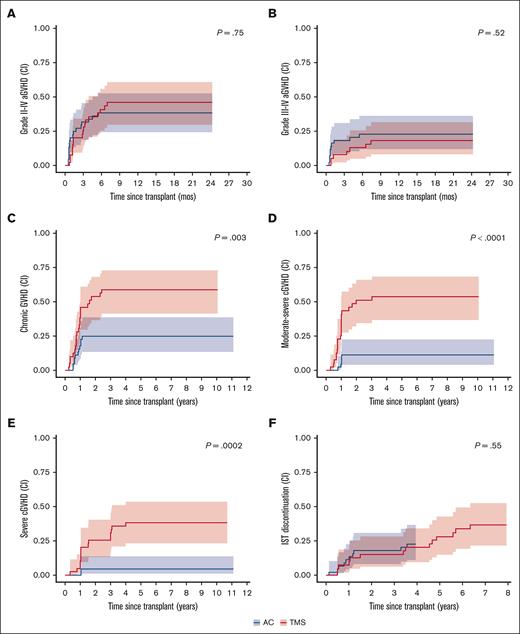

The cumulative incidence of aGVHD was similar between both arms for both grade 2 to 4 (32% in AC vs 31% in TMS; P = .75; Figure 2A) and grade 3 to 4 aGVHD (18% in AC vs 10% in TMS; P = .52; Figure 2B) at 100 and 180 days after transplant (Table 2). Organ-specific staging of aGVHD (supplemental Table 1) revealed that stage 3 to 4 aGVHD most commonly involved the gastrointestinal tract (AC, n = 7; TMS, n = 5), followed by liver (AC, n = 4; TMS, n = 2). Stage 3 skin involvement was seen in 2 patients on each arm, with no cases of stage 4 skin aGVHD.

GVHD Outcomes. (A) Cumulative incidence (CI) of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD. (B) CI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD. (C) CI of any cGVHD. (D) CI of moderate-severe GVHD. (E) CI of severe cGVHD. (F) CI of being taken off immunosuppressive therapy (IST); ∗all CIs reported are competing with death, relapse, or graft failure. For aGVHD, competing risks also include cGVHD (without prior acute). ∗P value for differences in cumulative incidence obtained using Gray method.

GVHD Outcomes. (A) Cumulative incidence (CI) of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD. (B) CI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD. (C) CI of any cGVHD. (D) CI of moderate-severe GVHD. (E) CI of severe cGVHD. (F) CI of being taken off immunosuppressive therapy (IST); ∗all CIs reported are competing with death, relapse, or graft failure. For aGVHD, competing risks also include cGVHD (without prior acute). ∗P value for differences in cumulative incidence obtained using Gray method.

The cumulative incidence of severe cGVHD was significantly lower with AC than with TMS at 1, 2, and 5 years (overall P = .0002): 0% vs 10% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.2-22.3), 4.5% (95% CI, 0.8-13.9) vs 25.6% (95% CI, 13.1-40.3) and 4.5% (95% CI, 0.8-13.9) vs 28.5% (95% CI, 23.0-53.7), respectively (Figure 2E; Table 2). Additionally, significantly lower cumulative incidences of any grade cGVHD (P = .003; Figure 2C) and moderate-severe cGVHD (P < .0001; Figure 2D) was seen with AC than with TMS prophylaxis.

Among those who developed cGVHD, the median time to initial onset of cGVHD was similar; 316 days (182-1031) in AC vs 301 days (72-870) in TMS arms. The maximum National Institutes of Health cGVHD global severity was mild, moderate, and severe in 5 (11%), 4 (9%), and 3 patients (7%) in the AC arm and in 1 (3%), 9 (23%), and 14 patients (36%) in TMS arm, respectively. Most patients had cGVHD of the skin (AC, n = 9 [22%] vs TMS, n = 21 [54%]), followed by oral (AC, n = 3 [7%] vs TMS, n = 17 [44%]) and ocular involvement (AC, n = 3 [7%] vs n = 14 [36%]; supplemental Table 2). By multivariable Cox regression, the only prognostic factor for development of severe cGVHD was treatment with TMS (hazard ratio [HR], 7.4; 95% CI, 1.7-32.5; P = .008; supplementary Tables 4-5). Late onset of cGVHD beyond 2 years after HSCT occurred in 3 patients at a median of 2.4 years (range, 2.3-2.9), with only 1 having a clear trigger with receipt of donor lymphocyte infusions for relapse.

For patients who developed any GVHD, the cumulative incidence of immunosuppression discontinuation at 3 years, competing with death or progression, was similar between both arms (AC, 22.7% vs TMS, 17.9%; overall P = .55; Figure 2F). At the time of analysis, 7 patients in each arm were permanently off systemic immunosuppression.

Toxicity and transplant-related mortality

The most common grade 3 to 4 adverse events within 100 days after transplant were infections, seen in 80% vs 54% of patients in AC vs TMS arms (P = .019; supplemental Table 3). More grade 3 to 4 bacterial infections were seen with AC (P = .004), with bacteremia and catheter-related infections being the most common. In terms of viral infections, a higher incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation was seen in the AC arm by day +100: 55% (95% CI, 39-68) vs 21% (95% CI, 10-34) (overall P = .030; supplemental Figure 3). One grade 3 infusion reaction related to alemtuzumab occurred.

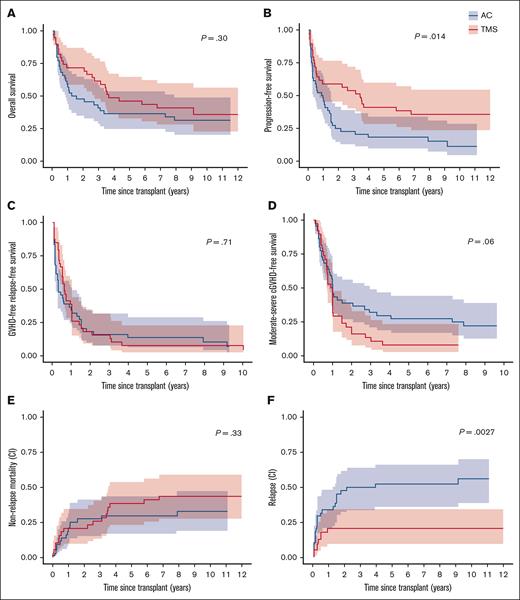

Treatment-related mortality at day 100 was 6.8% (95% CI, 1.7-16.9) with AC vs 10.3% (95% CI, 3.2-22.2) with TMS prophylaxis (P = .33). Treatment-related mortality in patients aged ≥60 years was 0% with AC vs 33.3% (95% CI, 9.3%-60.1%) with TMS (P = .26). Factors associated with increased treatment-related mortality included higher age at transplant (≥60 years vs <60 years; HR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.30-6.11; P = .009), positive recipient CMV status (HR, 3.16; 95% CI, 1.44-6.93; P = .004), and hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index (HCT-CI) score of ≥2 (HR, 7.73; 95% CI, 2.29-26.08; P = .001; supplementary Tables 6-7). Nonrelapse mortality (NRM) at 2 and 5 years was similar in both arms (P = .33; Figure 3E; Table 2). Causes of late NRM included pneumonia/respiratory failure (n = 4), metastatic secondary cancer (n = 2), TMA/respiratory failure due to cGVHD (n = 1), gastrointestinal obstruction complication (n = 1), and coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction (n = 1). Patients who experienced late NRM had lower absolute CD3 T cells at 1 year (567 vs 1057 cells per μL; P = .004) than nonlate NRM patients; as well as lower total CD4– (194 vs 372 cells per μL; P = .02) and CD8– (269 vs 624 cells per μL; P = .01) T-cell subsets.

Relapse and survival outcomes. (A) OS. (B) Progression-free survival. (C) GRFS. (D) Moderate-severe CFS. (E) Cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality competing with relapse. (F) Cumulative incidence of relapse competing with death. ∗P value for differences in survival estimates obtained from log-rank test; P value for differences in cumulative incidence obtained using Gray method.

Relapse and survival outcomes. (A) OS. (B) Progression-free survival. (C) GRFS. (D) Moderate-severe CFS. (E) Cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality competing with relapse. (F) Cumulative incidence of relapse competing with death. ∗P value for differences in survival estimates obtained from log-rank test; P value for differences in cumulative incidence obtained using Gray method.

Subsequent cancers after transplant developed in 13 patients (AC, n = 7; TMS, n = 6; P = .50) at a median of 4.5 months (range, 1-69) after HSCT. These included cases of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, nonmelanoma skin cancers, melanoma, thyroid cancer, lung cancer, and a donor-derived myeloid neoplasm.

Survival and relapse outcomes

With a median follow-up of 9.8 years (range, 5.2-12.6), no statistically significant differences were found in 5-year OS (36% vs 46%; P = .30) or GRFS (14 vs 8%; P = .71) between both treatment arms (Figure 3A,C; Table 2). There was a trend toward higher moderate-severe cGVHD-free survival (CFS) in the AC arm (27% [15-49] vs 8% [1-19]; P = .06; Figure 3D). By Cox model, adjusting for treatment arm (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.45-1.33; P = .35), age ≥60 years (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.26-4.07; P = .0062), HCT-CI score 2 to 4 vs 0 to 1 (HR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.38-5.34; P = .0038), and positive recipient CMV status (HR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.17-3.63; P = .013) were all jointly associated with poorer OS (supplemental Tables 8-9). A higher HCT-CI score (2-4) was also associated with poorer GRFS (HR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.25-3.47; P = .005) and moderate-severe CFS (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.11-3.26; P = .02) after adjusting for treatment arm and CD34 cells per kg (supplemental Tables 10-13). Recipient female sex was found to be associated with improved moderate-severe CFS (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.81; P = .006; supplemental Table 13).

Cumulative incidence of relapse competing with death at both 2 and 5 years was twofold higher in the AC arm vs TMS arm (48% [32-62] vs 21% [10-35] and 52% [36-66] vs 21% [10-35], respectively; P = .0027; Figure 3F). Sixteen patients (19.3%) received donor lymphocyte infusions (median, 1 infusion [range, 1-5]) for relapsed disease, of which 13 (81%) were on AC arm and 3 (19%) were on TMS arm. By multivariable analysis, factors associated with higher incidence of relapse included AC treatment arm (HR, 2.60 [1.22-6.10]; P = .022), ≥3 prior treatment regimens (HR, 2.70 [1.19-6.13]; P = .018), CD34 >8.1 (HR, 2.90 [1.39-6.07]; P = .0046), and intermediate-high Kahl Relapse risk score (HR, 2.32 [1.13-4.79]; P = .023; supplemental Tables 14-15). Late relapse (>2 years after HCT) occurred in 4% (n = 3) in AC arm at a median of 3.9 years (range, 2.1-9.2) after HCT; no relapses were seen beyond 1 year on the TMS arm. Higher relapse-related mortality was associated with older donor age (≥35 years vs 18-34 years [HR, 2.54 (1.04-6.20); P = .041]), after adjusting for treatment arm and number of prior treatments (supplemental Tables 16-17). Median progression-free survival was longer in TMS arm vs AC (41.1 months [6 to NE (not evaluable)] vs 10.9 months [3.3-17.9]; P = .014; Figure 3B).

Effect of baseline ALC on outcomes in AC arm

Among patients randomized to AC (n = 44), median absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) (day 8 before HSCT, first day of alemtuzumab infusion) and pretransplant CD4+ count was 2.85 × 109/L (0 × 109/L to 37.1× 109/L) and 0.09 × 109/L (0.01× 109/L to 0.9× 109/L), respectively. The high ALC (HiALC; n = 30; ALC ≥2 × 109/L) and low ALC (LoALC; n = 14; ALC <2 × 109/L) groups were similar in all examined baseline variables. After a median follow-up of 1.4 years (range, 0.1-11.5), estimated median OS was 1.4 years (95% CI, 0.7-7.3). Patients in the HiALC group had improved OS compared with LoALC group (3.2 years [1.6 to NE] vs 0.7 years [0.5 to NE]; P = .001) with 1-, 2-, and 5-year OS of 70% vs 29%, 63% vs 14%, and 47% vs 14%, respectively (supplemental Figure 7A). Median GRFS was 0.5 years (range, 0.2-1.5) and 0.3 (range, 0.1-3.9) for HiALC and LoALC group (P = .08), respectively (supplemental Figure 7B).

Immune reconstitution

Absolute lymphocyte count recovery to 500 per μL was significantly delayed in the AC arm (median, 76 vs 16 days; P < .0001). natural killer cell numbers were significantly reduced in AC vs TMS during the first month (P < .0001) but comparable by 100 days (Figure 4A). B-cell reconstitution was delayed in both arms but comparable after day +180. Delays in T-cell repopulation in the AC arm were profound at 6 months, with 24 months required for repopulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to levels comparable with TMS (Figure 4A). Global T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoires after transplant had significantly less diversity than those of their donors, consistent with early peripheral expansion of a limited TCR repertoire. Furthermore, the early repertoire diversity of most AC patients was more skewed and oligoclonal than in most TMS patients.

Immune Reconstitution. (A) Lymphocyte repopulation. Time course of lymphocyte subsets in AC (blue) and TMS (red) treatment arm patients at 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Medians are indicated as circles, 25th and 75th quartiles are shown as error bars. Circles placed below the x-axis indicate a median of 0 cells. For patient numbers and statistical disparity between arms at each T-cell time point, refer to supplemental Figure 5A. (B) Time course of changes in posttransplant TCR repertoire skewing. Repertoire skewing (oligoclonality) indices (RSI) determined for individual AC (blue circles) and TMS (red circles) patients at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months were compared between arms (top statistics) and with the RSI of their own allogeneic transplant donors (green triangles) (bottom statistics). Both CD4 (left graph) and CD8 cells (right graph) in the AC arm had more repertoire skewing (more oligoclonality) than those in most patients in the TMS arm or in their donor’s original T cells at 1, 3, and 6 months in CD4 and at 3 and 6 months in CD8 T cells. (C) Flow cytometry gating profiles of T lymphocytes at 6 months in the AC and TMS arms. CD4 cells were gated to distinguish Treg (thick outline) from non-Treg (conventional) CD4 T cells, based on Treg characterization as CD127–CD25++ CD4 cells. The non-Treg and Treg CD4 and the CD8 cells were then gated to assess naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+; thick outline), central memory (CD45RA–CCR7+), effector memory (CD45RA–CCR7–) and TEMRA (CD45RA+CCR7–) subsets. (D) Box and whisker plots of the percentage of Treg cells within the CD4 population (left graph) and the total number of Treg per μL (right graph) in AC (blue box) and TMS (orange box) patients at 6, 12, and 24 months after transplant. (E) Box and whisker plots of the numbers of naïve CD4 T cells per μL (left graph) and of naïve CD8 T cells per μL (right graph) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (F) Box and whisker plots of the ratios of the numbers of Treg to the number of naïve CD4 (left graph) or to the number of naïve CD8 T cells (right graph) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (G) Flow cytometry gating profiles of CD8 Tscm populations. TMS patient flow cytometry panels identifying naïve (CD45RA+ CCR7+) CD8 cells (thick line box) at 6, 9, and 12 months (left column), showing gating on the CD8naïve (arrows) to identify CCR7dimCD95+ Tscm at 3 sequential time points (right column). The patient shown developed moderate cGVHD at 9 months. (H) Box and whiskers plot comparing the number of CD8 Tscm per μL in AC (blue box) and TMS (orange box) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (I) Scatterplot of individual AC (blue circle) and TMS (red circle) patients as assessed for the ratio of Treg per μL to CD8naïve per μL vs the number of Tscm per μL. In all box and whisker plots, the number of patients assayed at each time point in each arm is shown in supplemental Figure 5C. In all graphs, AC arm patients are shown in blue box and TMS in orange box; boxes define the median, 25th and 75th quartiles; and whiskers show minimum and maximum values. Mann-Whitney unpaired nonparametric statistics were performed to compare AC and TMS lymphocyte numbers, RSI, and lymphocyte subpopulations and ratios; shown as stars: ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗ P < .05. NK cell, natural killer cell.

Immune Reconstitution. (A) Lymphocyte repopulation. Time course of lymphocyte subsets in AC (blue) and TMS (red) treatment arm patients at 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Medians are indicated as circles, 25th and 75th quartiles are shown as error bars. Circles placed below the x-axis indicate a median of 0 cells. For patient numbers and statistical disparity between arms at each T-cell time point, refer to supplemental Figure 5A. (B) Time course of changes in posttransplant TCR repertoire skewing. Repertoire skewing (oligoclonality) indices (RSI) determined for individual AC (blue circles) and TMS (red circles) patients at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months were compared between arms (top statistics) and with the RSI of their own allogeneic transplant donors (green triangles) (bottom statistics). Both CD4 (left graph) and CD8 cells (right graph) in the AC arm had more repertoire skewing (more oligoclonality) than those in most patients in the TMS arm or in their donor’s original T cells at 1, 3, and 6 months in CD4 and at 3 and 6 months in CD8 T cells. (C) Flow cytometry gating profiles of T lymphocytes at 6 months in the AC and TMS arms. CD4 cells were gated to distinguish Treg (thick outline) from non-Treg (conventional) CD4 T cells, based on Treg characterization as CD127–CD25++ CD4 cells. The non-Treg and Treg CD4 and the CD8 cells were then gated to assess naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+; thick outline), central memory (CD45RA–CCR7+), effector memory (CD45RA–CCR7–) and TEMRA (CD45RA+CCR7–) subsets. (D) Box and whisker plots of the percentage of Treg cells within the CD4 population (left graph) and the total number of Treg per μL (right graph) in AC (blue box) and TMS (orange box) patients at 6, 12, and 24 months after transplant. (E) Box and whisker plots of the numbers of naïve CD4 T cells per μL (left graph) and of naïve CD8 T cells per μL (right graph) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (F) Box and whisker plots of the ratios of the numbers of Treg to the number of naïve CD4 (left graph) or to the number of naïve CD8 T cells (right graph) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (G) Flow cytometry gating profiles of CD8 Tscm populations. TMS patient flow cytometry panels identifying naïve (CD45RA+ CCR7+) CD8 cells (thick line box) at 6, 9, and 12 months (left column), showing gating on the CD8naïve (arrows) to identify CCR7dimCD95+ Tscm at 3 sequential time points (right column). The patient shown developed moderate cGVHD at 9 months. (H) Box and whiskers plot comparing the number of CD8 Tscm per μL in AC (blue box) and TMS (orange box) at 6, 12, and 24 months. (I) Scatterplot of individual AC (blue circle) and TMS (red circle) patients as assessed for the ratio of Treg per μL to CD8naïve per μL vs the number of Tscm per μL. In all box and whisker plots, the number of patients assayed at each time point in each arm is shown in supplemental Figure 5C. In all graphs, AC arm patients are shown in blue box and TMS in orange box; boxes define the median, 25th and 75th quartiles; and whiskers show minimum and maximum values. Mann-Whitney unpaired nonparametric statistics were performed to compare AC and TMS lymphocyte numbers, RSI, and lymphocyte subpopulations and ratios; shown as stars: ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗ P < .05. NK cell, natural killer cell.

Analyses of T subset reconstitution revealed that the percentages of Treg cells within the CD4 population did not differ between the arms at any time point (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 6). Because of the marked early disparity in CD4+ T-cell numbers per μL, however, the number of Treg per microliter in AC was significantly lower than that of TMS patients at 6 (P < .0001) and 12 months (P = .003) and became equivalent by 24 months (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 5B).

Both the percentages and the total number per microliter of recent thymic emigrant and naïve Treg and non-Treg CD4+ and naïve CD8+ T cells were significantly lower in AC than in TMS (all P < .0001) at 6 months. (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 5C,6). By 24 months, however, AC naïve populations became comparable with TMS through renewed thymopoiesis, as indicated by 10- to 100-fold increases in median recent thymic emigrant and naïve T cells per microliter. In the TMS population, in contrast, no significant increase in naïve T cells occurred from 6 to 24 months.

Although the AC arm protocol resulted in severe quantitative reductions in both Treg and Tnaïve populations, the ratio of Treg cells per microliter to non-Treg CD4naïve cells per microliter or of Treg per microliter to CD8naïve per microliter was significantly higher in AC than in TMS (P = .0001; each for CD4 and CD8 naïve cells; Figure 4F). Median ratios of Treg to naïve T cells were almost 10-fold higher in AC than in the TMS arms. Onset of most cGVHD in both arms occurred between 6 and 12 months, that is, in the months after the greatest disparity in the ratios of Treg and Tnaïve cells.

At 6 months, the naïve CD8 population in AC patients were mainly memory stem T cells (Tscms; CD45RA+CCR7dimCD95+; Figure 4C), but the overall numbers of CD8 naïve and hence CD8 Tscms per microliter were very low (Figure 4H). In the TMS arm, in contrast, the Tscm cells were not only present as a visible component within the total naïve CD8 cell populations (Figure 4G) but also persisted at increasing frequency and higher numbers during the main period of cGVHD onset (Figure 4G-H). Finally, when the individual AC and TMS patients at 6 months were plotted comparing the ratio of Treg to CD8+ naïve cells vs the number of CD8+ Tscm, the 2 T-cell population parameters were strongly correlated (ρ = –0.72; P < .0001), but the 2 patient protocol arms were sharply distinct (Figure 4I).

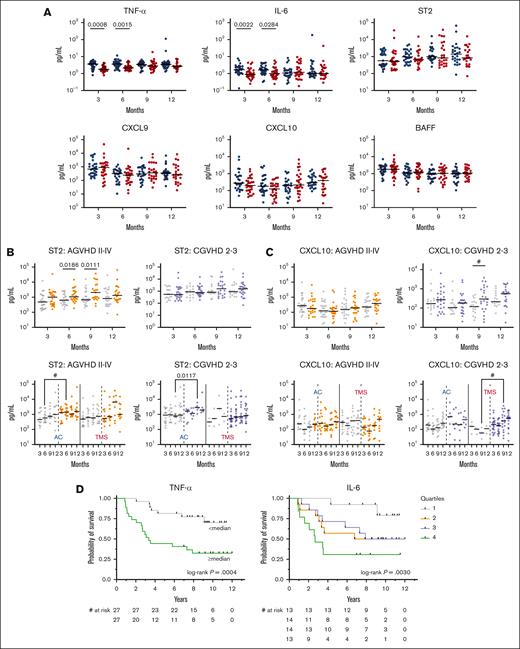

Cytokines

Upon evaluation of post-HSCT cytokine levels, patients in the AC arm had higher levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) at 3 and 6 months after transplant, with no differences between arms at any time point in levels of ST2, CXCL9, CXCL10, or BAFF (Figure 5A). Patients who developed aGVHD within 180 days after transplant, excluding patients with prior relapse/progression, had significantly higher levels of ST2 at 6 and 9 months (with a trend at 3 months P = .07; Figure 5B). A trend toward higher CXCL10 at 9 months was associated with moderate-to-severe cGVHD (Figure 5C). No other difference was found in levels of cytokines, including BAFF and CXCL9, for patients who developed moderate-to-severe CGVHD (supplemental Figure 8). Higher levels of IL-6 and TNF-α at 6 months were strongly associated with worse OS (Figure 5D) after adjusting for other important factors including treatment arm, age ≥60 years, recipient CMV status, and HCT-CI ≥2 (supplemental Table 18).

Cytokine analysis. (A) Trends in cytokine levels compared between arms AC (blue circles) vs TMS (red circles) at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after HSCT. (B) Trend and differences between ST2 levels after HSCT among patients who did (orange circles) or did not (gray circles) develop grade 2 to 4 aGVHD; and did (purple circles) or did not (gray circles) develop moderate-to-severe cGVHD. (C) Trend and differences between CXCL10 levels after HSCT among patients who did (orange circles) or did not (gray circles) develop grade 2 to 4 aGVHD; and did (purple circles) or did not (gray circles) develop moderate-to-severe cGVHD. (D) Higher levels of TNF-α and IL-6 at 6 months were associated with worse OS. TNF-α median, 2.7 pg/mL; IL-6 quartiles: Q1 <0.84 pg/mL; Q2 0.84 to 1.3 pg/mL; Q3 >1.3 to 2.2 pg/mL; Q4 >2.2 pg/mL. # indicates P value <.05; q value > 0.05.

Cytokine analysis. (A) Trends in cytokine levels compared between arms AC (blue circles) vs TMS (red circles) at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after HSCT. (B) Trend and differences between ST2 levels after HSCT among patients who did (orange circles) or did not (gray circles) develop grade 2 to 4 aGVHD; and did (purple circles) or did not (gray circles) develop moderate-to-severe cGVHD. (C) Trend and differences between CXCL10 levels after HSCT among patients who did (orange circles) or did not (gray circles) develop grade 2 to 4 aGVHD; and did (purple circles) or did not (gray circles) develop moderate-to-severe cGVHD. (D) Higher levels of TNF-α and IL-6 at 6 months were associated with worse OS. TNF-α median, 2.7 pg/mL; IL-6 quartiles: Q1 <0.84 pg/mL; Q2 0.84 to 1.3 pg/mL; Q3 >1.3 to 2.2 pg/mL; Q4 >2.2 pg/mL. # indicates P value <.05; q value > 0.05.

Discussion

cGVHD remains a major barrier to successful allo-HSCT despite progress in preventive and treatment strategies over the last 2 decades.1,3 This randomized study using a RIC transplant platform demonstrates high and clinically significant potency of a lymphodepleting high-dose alemtuzumab-based regimen in prevention of severe cGVHD. The described post-HCT immune reconstitution with alemtuzumab-based lymphodepletion could potentially inform design of improved future GVHD prophylaxis platforms. Differences in T-cell repopulation after transplant may have been key factors in the greater incidence, severity, and persistence of cGVHD observed in the TMS than the AC arm. The profound depletion of T cells, particularly naïve cells, in the AC arm limited the numbers of immunocompetent T cells and early TCR repertoire diversity. Depletion of naïve T cells also resulted in fivefold to 10-fold higher median ratios of both Treg to naïve non-Treg CD4 cells per microliter and of Treg to naïve CD8 cells per microliter in AC than in TMS at 6 months. The high Treg:Tn ratio in AC may preclude escape of allo-reactive T cells from Treg control,53 while permitting it in TMS. Finally, a large CD8+ Tscm population emerged in TMS by 6 months, at the end of immunosuppression, but before most cGVHD onset. These Tscms expanded and persisted in many patients with cGVHD, consistent with growing evidence that Tscms play a role in cGVHD.54,55 Thus, disparities in repopulation of naïve, regulatory, and Tscm T cells may have mediated the differential cGVHD outcome in this trial.

Although no differences were seen in aGVHD between arms, the incidence of any grade, moderate-severe, and severe cGVHD were significantly lower with lymphodepletion by alemtuzumab. Despite the significant prevention of cGVHD seen with AC, the benefit was offset by increased relapse, as demonstrated by the longer progression-free survival in the TMS cohort, as well as increased infection. However, these did not translate into any difference in OS, GRFS, or NRM between both arms. In terms of infections, this study was conducted in the era before the regular use of letermovir prophylactic therapy against CMV,56 and whether the same pattern of CMV reactivation would be replicated in the current era would be of interest. In terms of relapse rate, it is noteworthy that the study population was defined by high-risk characteristics (with 51% having HCT-CI ≥3, 19% karnofsky performance status (KPS) 60%-80%, and 40% Kahl high risk) and diverse underlying hematologic malignancies. If viral reactivation and relapsed disease risk can be mitigated, then AC would offer a clear advantage in terms of cGVHD protection. In transplant settings in which relapse is not of concern, such as nonmalignant conditions, alemtuzumab is increasingly being used for this reason.57 The rate of permanent immunosuppressive therapy (IST) discontinuation at 3 years (with relapse and death as competing risks) was 22.7% and 17.9% for AC and TMS arms, respectively, which is comparable with that reported from similar lymphodepletion (LD)-focused trials of 3-year IST-free survival of 17%.8 Transplant success should be weighed heavily upon maximizing this IST-free survival end point.

Patients with aGVHD grade 3 to 4 had higher median levels of ST2, whereas those with moderate-to-severe cGVHD had higher median levels of CXCL10. Although elevated ST2 has been previously associated with aGVHD and NRM,58 cytokine analyses revealed that only patients from the AC arm who developed aGVHD grade 3 to 4 and moderate-to-severe cGVHD showed a statistical association with higher ST2 levels at 6 and 9 months, respectively.

Despite prior described associations of cGVHD diagnosis or severity with cytokines such as BAFF and CXCL9,59 we did not find any predictive value or difference among these cytokine levels in this prospective longitudinal study in patients who did or did not develop cGVHD, which speaks to the continued challenge of identifying reliable predictive biomarkers for cGVHD. Finally, when adjusted for other variables associated with OS (recipient CMV status, HCT-CI≥2, and age ≥60 years), higher levels of IL-6 and TNF-α at 6 months for the whole cohort were associated with worse OS; a finding that warrants further larger scale validation. Although these correlative cytokine results may not be extrapolatable to other lymphodepletive strategies such as PT-Cy, they may serve as a source of hypothesis generation for future studies of biomarker development.

This study’s strength as a single-center trial was that it allowed for a cohesive methodology in a well-controlled setting. Furthermore, although cGVHD incidence was our primary end point, we report an extended duration of follow-up, which allows for a definitive assessment of the impact of cGVHD on other late effects on critical clinical outcomes This provides valuable insight on the long-term sequelae related to cGVHD that are crucial to the definitive success of transplant for survivors, including surveillance and prevention of late NRM, late relapse, and subsequent malignancies. Thirteen patients developed subsequent malignancies, including 4 cases of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (3 in AC arm and 1 in TMS), which has a well-known association with lymphodepletion.37 Notably, 2 of these second cancer cases developed into metastatic disease and were an important cause of late NRM, which emphasizes the need for close monitoring of our HSCT survivors for subsequent malignancies. Most cases of late NRM, defined as NRM beyond 2 years after HSCT, occurred in patients in the TMS arm (n = 9 vs n = 2 in AC arm), and most were due to pneumonia or respiratory failure.

Limitations of this study include that ∼20% of patients received grafts from 7/8 mismatched unrelated donor (mMUD), which can increase risk of GVHD; however, this factor was balanced among arms. Additionally, the distribution of hematologic malignancy indication for transplant in this study included more patients with lymphoma than would be expected to in our contemporary transplant landscape, which is predominantly myeloid malignancies and thus may influence treatment outcomes, because lymphoid diseases are more salvageable to donor lymphocyte infusion and adoptive cell therapies. However, this study was conducted in the pre-CAR-T era. Notably, we did not systematically collect data on pre-HSCT measurable residual disease yet acknowledge that this should be included in future studies because it can significantly affect relapse risk in the RIC setting.60,61

Another limitation is that alemtuzumab pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies were not incorporated into this study. Compared with proximal dosing, administering alemtuzumab more distally during transplant conditioning has also been shown to lead to less mixed chimerism and higher event-free survival in transplant studies for nonmalignant indications.38 However, because our primary study goal was cGVHD prevention, we elected a more proximal approach to maximize the effect on T cells in the graft rather than in the recipient. Our report provides novel and important immunological takeaways of the effect lymphodepletion as a method of cGVHD prevention, with the consideration that some of the toxicity seen (higher infections and relapse) may be attributed to the high exposure of alemtuzumab, which could be further optimized with dosing adjustments either based on weight or other variables such as ALC. This conclusion is also strengthened by our ALC subgroup analysis regarding lower ALC (<2.0 × 109/L) at the time of alemtuzumab infusion associated with inferior survival in the AC arm than those with higher baseline ALC (≥2.0 × 109/L). This finding is consistent with other reports10,62,63 of ALC at the time of conditioning administration influencing transplant outcomes and warrants further study of ALC-based dosing for alemtuzumab.

In terms of optimal in vivo lymphodepletion strategy, much enthusiasm has accompanied the tremendous success of PT-Cy, which has allowed for safe haplo HSCTs with improved rates of GVHD and survival and has become standard of care in this haplo setting.13,38,64 Studies have expanded its use to HLA-matched related donor (MRD) or matched/mismatched unrelated donors. PT-Cy compared with ATG in a study using MUDs led to similar rates of aGVHD, extensive cGVHD, 2-year OS, and relapse among both cohorts65; whereas a study using MRD66 showed lower rates of cGVHD among the ATG group and no difference in other outcomes. No studies have been reported comparing PT-Cy with alemtuzumab to date. Three recently reported randomized studies41,67-69 evaluated PT-Cy compared with other standard prophylaxis after RIC allo-HSCT using a MUD/MRD, in which PT-Cy led to decreased rates of cGVHD, improved GRFS, but no difference in OS. PT-Cy has therefore moved to the forefront of current practice in cGVHD prevention for RIC allo-HCT, although more data will be needed to better understand the long-term effects on organ toxicity, relapse, secondary malignancies, and, ultimately, OS.

In summary, an alemtuzumab-based platform after RIC transplant using MUD PBSCs robustly reduced the rate and severity of cGVHD compared with standard pharmacologic prophylaxis. A distinct immunomodulatory profile after AC may have caused reduced cGVHD incidence and severity, however, increased infections and relapsed malignancy resulted in a lack of survival benefit. Improved strategies to mitigate the associated risks of relapse and infectious toxicities in RIC allo-HSCT setting are needed. Future studies should focus on developing better cGVHD risk-stratification systems to identify those patients who may most benefit from antibody lymphodepletion vs other prevention approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Robert Soiffer for his expert review and comments on this manuscript and Liang Cao, Brian Yagi, Daniel Peaceman, and David Moorshead for their contributions to the cytokine and immunology data collection, processing, and analysis for this manuscript.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this work do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government.

Authorship

Contribution: S.Z.P., M.R.B., D.H.F., F.T.H., and R.E.G. planned the clinical trial and experiments; F.T.H., J.R., and S.M. conducted correlative experiments; S.Z.P., M.R.B., S.M.S., L.M.C., A.O., N.G.H., E.S., F.T.H., J.R., and R.K. analyzed and interpreted data; S.Z.P., M.R.B., L.M.C., R.B.S., B.C.S., J.S.W., T.E.H., J.C.G.-B., and D.H.F. provided patient care and implemented protocol-directed procedures; L.M.C., N.G.H., and F.P. wrote the first versions of manuscript; and all authors read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest discosure: S.Z.P. received research support from the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute through the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program, which includes Clinical Research Development Agreements with Celgene, Actelion, Eli Lilly, Pharmacyclics, and Kadmon Corporation. B.C.S. reports consultancy with Hansa Biopharma and Gamida Cell; and research support from Miltenyi Biotec. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven Z. Pavletic, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Building 10-Hatfield CRC, Room 4-3130, Bethesda, MD 20892-1203; email: pavletis@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

M.R.B. and S.Z.P. are joint senior authors and contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Steven Z. Pavletic (pavletis@mail.nih.gov).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.