Key Points

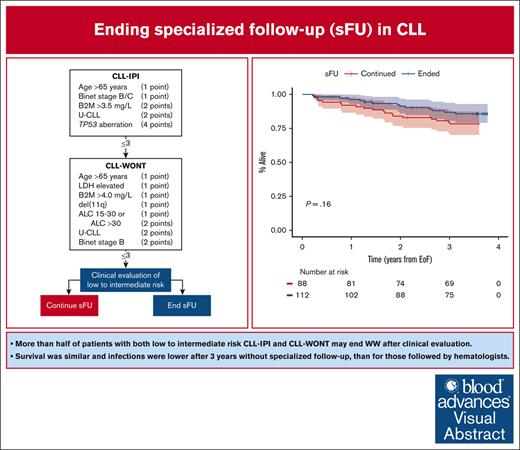

More than half of patients with low-to-intermediate risk CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT may safely end sFU.

Survival was similar and time to infection was longer in patients ending sFU compared with those who continued.

Visual Abstract

Approximately half of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) will never require treatment; nonetheless, they are recommended life-long specialized follow-up (sFU). To prioritize health care resources, local hospital management implemented ending sFU in asymptomatic patients with CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) and CLL without need of treatment (CLL-WONT) low-to-intermediate risk, who were covered by universal health care. To evaluate the feasibility and safety of ending sFU, we investigated 3-year clinical outcomes among 112 patients selected by clinical assessment to end sFU as compared with 88 patients selected to continue sFU. Patients who ended sFU were older, but otherwise lower risk compared with patients continuing sFU. Overall survival (OS) was similar in patients ending and continuing sFU (3-year OS, 87% and 80%, respectively; P = .16). Hospital visits per patient-year were lower (median 0.7 vs 4.3, P < .0001) and time to first infection was longer (P = .035) in patients ending sFU compared with those who continued sFU, including shorter in-hospital antimicrobial treatment (median 4 vs 12 days, respectively; P = .026). Finally, 1 in 6 patients were rereferred, including 4 patients meeting international workshop on CLL criteria for need of treatment. This also resulted in a lower 3-year first treatment rate for patients ending sFU compared with patients continuing sFU (4% vs 23%, respectively; P < .0001). In conclusion, it is feasible and safe to end sFU for patients with CLL who have low-to-intermediate risk CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT scores upon thorough clinical evaluation before ending sFU.

Introduction

The vast majority of patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) present without an indication for treatment and are typically followed by standard-of-care (SOC) watch and wait (WW) until CLL progression or death.1 Specialized follow-up (sFU) of asymptomatic patients in WW usually includes physical examination and blood tests every 3 to 12 months guided by risk of CLL progression, including use of the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI).2,3 However, most patients will never require CLL treatment and may thus be subjects to endless monitoring without clinical consequence. From the patients’ perspective, WW is often perceived as “watch and worry” and is associated with psychological distress related to frequent hospital visits.4,5 CLL treatment is indicated upon iwCLL criteria,1 and according to the international prognostic score for early-stage CLL (IPS-E), 8% and 61% of patients with low and high risk, respectively, are treated within 5 years.3

Although early detection leads to improved prognoses in almost every cancer,6 early detection of indolent cancers such as CLL that may never require treatment will only prolong the years alive with an incurable cancer, without clear data on improved overall survival (OS) or quality of life.7,8 So far, studies of preemptive treatment in early-stage CLL have failed to improve clinically meaningful outcomes, and thus WW continue to be the SOC in asymptomatic early-stage CLL.9,10 Thus, ending specialized surveillance for patients identified with the lowest of risks to progress toward need of treatment may be an attractive option for patients and for prioritization of health care resources, especially in countries with an increasing elderly population, which today challenges universal health care systems and require prioritization of available utilities by policymakers and physicians alike.11

We recently developed and validated a prognostic index for CLL without need of treatment (CLL-WONT) to identify patients with low (0-1 points), intermediate (2-3 points), high (4-5 points), and very high risk (6-10 points) of treatment using 7 risk factors:

age >65 years (1 point)

elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH: 1 point)

elevated beta-2-microglobulin (1 point)

unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene (IGHV:1 point)

del(11q) and/or del(17p) (1 point)

absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 15 × 109/L to 30 × 109/L (1 point) or >30 × 109/L (2 points)

Binet stage B/C (2 points)11

Furthermore, we proposed to end endless monitoring of asymptomatic patients with both CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT lower risk. To prioritize health care resources, this approach was approved and implemented by local hospital management from November 2019, allowing specialists to stop monitoring patients with low-to-intermediate CLL-WONT risk, who also had low-to-intermediate risk CLL-IPI. Instead of sFU, we simply recommended vaccination against Pneumococci and seasonal influenza and contacting their primary health care provider upon B symptoms or infectious symptoms. Of note, all Danish residents have access to free-of-charge (ie, tax paid) universal health care, also including rereferral to specialized care by general practitioners. The implementation antedated the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic by 5 months, and all patients had priority access to recommended vaccines against COVID-19 as they were approved.

To investigate the feasibility of stopping sFU in asymptomatic patients with lower-risk CLL, we here present safety data with a 3-years follow-up for patients who ended sFU as compared with those who continued SOC monitoring with a specialist.

Methods

All data were retrieved from the Danish Lymphoid Cancer Research (DALY-CARE) data resource as previously described.11 We retrieved information on all patients registered with CLL (DC91.1) at our institution from electronic health record (EHR) data. To calculate CLL-WONT scores,11 baseline data on age, Binet stage, IGHV status, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and information on treatment and survival were retrieved from the Danish CLL Register,12 and information on ALC and LDH was retrieved from the Clinical Laboratory Information System.13

We included all patients who were treatment-naïve and alive by 1 November 2019 and excluded patients with high and very high risk CLL-WONT and/or CLL-IPI. We initially reviewed all EHRs to look for indication of continuing sFU including B-symptoms, short lymphocyte doubling time, autoimmune cytopenias, severe immune dysfunction, and need for supportive care, such as prophylactic antibiotics or immunoglobulin replacement therapy. In case of suspected severe immune dysfunction or considered at high risk of infection, SOC sFU was continued. Patients without any indication of the above precautions were selected to end sFU.

The primary outcome of this study was 3-year OS. Secondary outcomes included health care utilization measured as hospital contacts, time to first infection, duration of infections, 3-year rereferral rate, and time to first treatment (TTFT). Because the decision to stop sFU was based on a clinical evaluation on top of CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT risk assessment, we present real-world outcomes rather than clinical trial data, and a power calculation may thus only provide guidance. Nevertheless, to detect a 15% survival difference, a 2-way power calculation indicated a sample size of 200 patients equally assigned to ending or continuing sFU (α = 0.05 and 1-β = 80%).

We used automatically retrieved EHR data through the DALY-CARE data resource to retrieve information on date of ending sFU, death, rereferral, and CLL treatment. We calculated time from ending sFU to event using the Kaplan-Meier method, censoring upon death for time of first infection, time to rereferral, and TTFT. The last date of follow-up was 15 August 2023. To allow for a comparison of clinical outcomes in patients ending and continuing sFU, we used the median date of ending sFU as a date of pseudo-ending WW in patients, who actually continued sFU at our department. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare baseline characteristics in the 2 cohorts, and log-rank tests were used to compare differences in Kaplan-Meier analyses. We used administered antimicrobials as a proxy for in-hospital treated infections. Data were retrieved from EHR admissions and medication data using anatomical therapeutic chemical codes (J01A, J02A, J01C, J01D, J01E, J01F, J01M, J01X, J05A, and P01A) excluding antimicrobials commonly used as prophylaxis (ie, sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim [J01EE01], acyclovir [J05AB01], and valacyclovir [J05AB11]). Antimicrobials discontinued for <14 days were considered as a single infection. Information on COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests from both test centers and hospitals was retrieved from EHR microbiology charts, and positive PCR tests >3 months apart were considered as separate infections.14

The management of our department approved ending specialized follow-up as an intervention to prioritize health care resources. Collection of data was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and National Ethics Committee (approvals P-2020-561 and 1804410, respectively). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

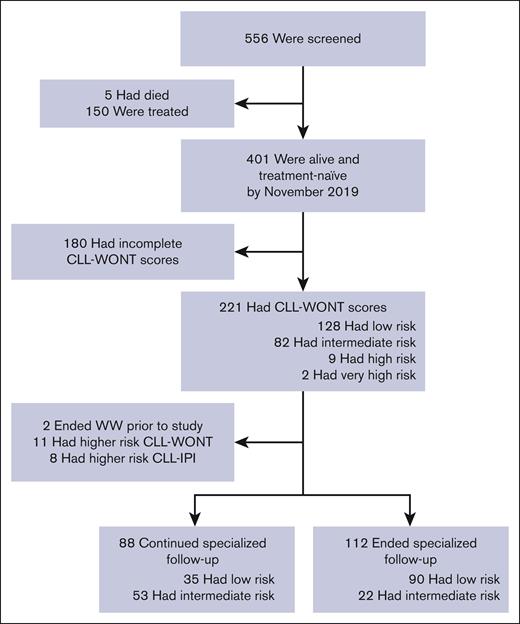

We screened a total of 556 patients, of whom 401 were alive and treatment-naïve by November 2019. CLL-WONT risk scores could be calculated in 221 patients, including 202 with low-to-intermediate risk CLL-WONT and CLL-IPI: 2 patients who were at low risk had ended sFU before November 2019 and were excluded. In total, 200 patients were eligible: 125 were low risk (62.5%) and 75 (37.5%) were intermediate risk (Figure 1). After a median of 4.2 years (interquartile range [IQR], 2.8-6.7) and 3.7 years (IQR, 2.6-4.9; P = .074) from time of CLL diagnosis, 112 (56%) and 88 (44%) patients ended and continued sFU, respectively. The median date of ending sFU was 5 January 2020 (IQR, 1 November 2019 to 25 February 2020), which was used as date of pseudo-ending specialized care in patients who in fact continued sFU (see “Methods”). As detailed in Table 1, patients ending sFU were older with lower ALC and more frequent mutated IGHV status than those continuing follow-up (P ≤ .0058). As a result, patients ending sFU were lower-risk CLL-WONT and CLL-IPI than patients who continued sFU (P < .0001).

CONSORT diagram of ending and continuing WW. Among 556 screened patients, 200 patients with both CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT low-to-intermediate risk were included in the study; 112 patients ended and 88 continued sFU.

CONSORT diagram of ending and continuing WW. Among 556 screened patients, 200 patients with both CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT low-to-intermediate risk were included in the study; 112 patients ended and 88 continued sFU.

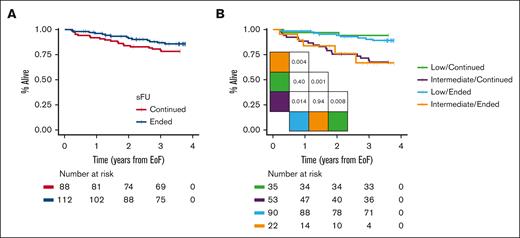

We observed patients for a median duration of 3.7 years (IQR, 3.6-3.7) from time of ending sFU or until 5 January 2020. After 3 years, OS rates were 87% (95% confidence interval, 71-88) for patients no longer followed by a specialist and 80% (95% confidence interval, 81-94) for those continuing sFU (Figure 2A; P = .16). Regardless of whether patients ended or continued sFU, we demonstrated similar 3-year OS when stratified for CLL-WONT low risk (90% vs 94%, respectively; P = .40) and intermediate risk (Figure 2B; 67% vs 70%, respectively; P = .94). Overall, 14 of the 112 patients without sFU had died: 4 patients (4%) died of infections (2 with evidence of bacterial pneumonia, 1 of sepsis and concurrent COVID-19, and 1 patient as a result of recurrent bacterial infections), 3 patients (3%) died of solid cancer, 3 patients (3%) died due to recent surgery or trauma without evidence of thrombocytopenia, 2 patients (2%) of myocardial infarction, 1 patient (1%) due to progressive Alzheimer disease, and 1 patient with unknown cause of death. Among the 88 patients who continued sFU, 19 patients had died: 7 (8%) died of infections (3 with COVID-19 and 4 with sepsis), 4 (5%) of solid cancer, 4 (5%) of cardiac disease, and 1 each of progressive Alzheimer disease (1%), cerebrovascular disease (1%), recent trauma (1%), and of unknown cause of death (1%).

OS. (A) OS in patients ending continuing sFU and (B) OS stratified based on CLL-WONT risk. Pairwise log-rank tests indicated.

OS. (A) OS in patients ending continuing sFU and (B) OS stratified based on CLL-WONT risk. Pairwise log-rank tests indicated.

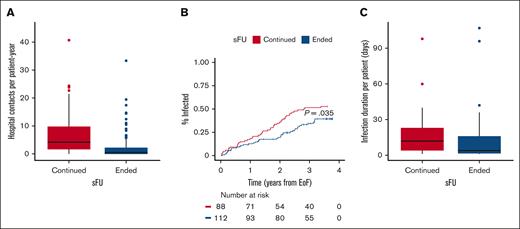

Next, we analyzed health care utilization and in-hospital infections in the 2 patient groups who both had access to universal health care. Among 2811 hospital contacts in total, patients who ended and continued sFU had 873 (31%) and 1938 (69%) contacts, respectively (P < .0001); regardless of whether patients were later rereferred. The median number of hospital visits per patient-year was also significantly lower for patients ending than for patients continuing sFU (0.7 [IQR, 0.0-2.5] vs 4.3 [IQR, 1.7-10.3]; P < .0001), respectively (Figure 3A). Based on in-hospital antimicrobial use, we recorded 161 infections: 72 (45%) infections in 39 of 112 (35%) patients ending sFU and 89 (55%) infections in 45 of 88 (51%) patients continuing sFU (P = .030). As a result, the time to first infection was also significantly longer in patients ending sFU than in those continuing (Figure 3B; P = .035), and patients ending sFU also demonstrated significantly shorter duration of in-hospital infections than those who continued sFU (4 [IQR, 1.5-16.0] vs 12 [IQR, 4-23] days, respectively; P = .026; Figure 3C). In patients ending and continuing sFU, the number of performed COVID-19 PCR tests was similar (811 [51%] and 785 [49%], respectively): the median number of PCR tests per patient was 4 (IQR, 2-10) and 5.5 (IQR, 2.0-12.2; P = .22), respectively. With 86 COVID-19 infections in 78 patients, the mean number of COVID-19 infections per patient was lower but not statistically different for patients ending vs continuing sFU (0.3 [standard deviation 0.5] vs 0.5 [standard deviation 0.6], respectively; P = .071); 1 of 39 (3%) and 9 of 47 (19%) COVID-19 infections occurred after CLL treatment in patients who had ended and continued sFU, respectively (P = .040).

Health care utilizations. (A) The median number of hospital visits per patient-year was 0.7 (IQR, 0.0-2.5) among patients ending sFU (blue) as compared with 4.3 (IQR, 1.7-10.3) for patients continuing sFU (red); P < .0001. (B) Time to first infection according to whether patients continued (red) or ended sFU (blue); P = .035. (C) The median number of days requiring in-hospital antimicrobial treatment was 12 (IQR, 4-23) and 4 days (IQR, 1.5-16.0) for patients continuing (red) and ending (blue) sFU, respectively; P = .026.

Health care utilizations. (A) The median number of hospital visits per patient-year was 0.7 (IQR, 0.0-2.5) among patients ending sFU (blue) as compared with 4.3 (IQR, 1.7-10.3) for patients continuing sFU (red); P < .0001. (B) Time to first infection according to whether patients continued (red) or ended sFU (blue); P = .035. (C) The median number of days requiring in-hospital antimicrobial treatment was 12 (IQR, 4-23) and 4 days (IQR, 1.5-16.0) for patients continuing (red) and ending (blue) sFU, respectively; P = .026.

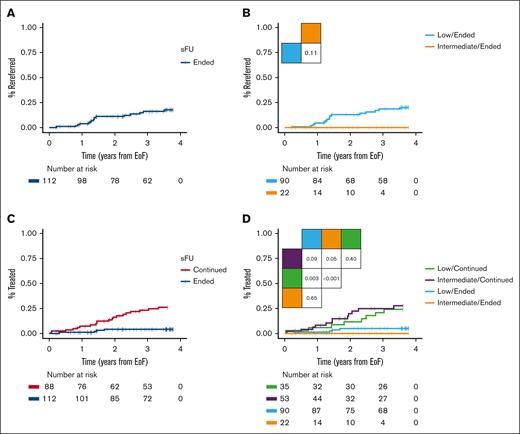

Among the 112 patients who ended sFU, the 3-year rereferral rate was 16% (18% for low risk and 0% for intermediate risk; Figure 4A-B). Of the total of 19 rereferred patients, 3 immediately ended sFU, 12 continued sFU in WW, and 4 patients were rereferred with iwCLL criteria for treatment being met, thus started treatment within 8 to 112 days. One patient received palliating chlorambucil because of a concomitant terminal bladder cancer, another received bendamustine plus rituximab, the third patient was included in a clinical trial of ibrutinib plus venetoclax (I+V),15 and the fourth patient was rereferred with Richter transformation and obtained a complete metabolic remission after 6 cycles of standard rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Another patient with atypical CLL was reclassified upon rereferral as having CD5+ Waldenström macroglobulinemia with a low immunoglobulin M monoclonal protein and thus censored from further follow-up. By contrast, 20 of the 88 patients continuing sFU received CLL treatment: 4 patients received chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab (G-Clb), 6 received bendamustine plus rituximab, 1 received fludarabine and cyclophosphamide plus rituximab, 1 received ibrutinib, 3 received acalabrutinib, 2 received venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, and 3 received I+V. Yet another patient received rituximab with dexamethasone owing to autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Of note, only 1 patient who was rereferred died of a terminal bladder cancer, whereas 3 patients who had initially continued specialized monitoring had also died after each receiving G-Clb, acalabrutinib, and I+V. Consequently, patients ending sFU had longer TTFT as compared with patients continuing sFU (3-year TTFT rates 4% and 23%, respectively; Figure 4C; P < .0001). For patients ending vs continuing sFU, the 3-year TTFT rates in patients who were at low risk were 5% and 21%, respectively (P = .0031), and 0% and 25% for those with intermediate risk, respectively (Figure 4D; P = .054). Similar TTFT was seen for patients with low and intermediate risk, who either ended or continued sFU (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 1; P ≥ .40). In subgroup analyses of low and intermediate risk CLL-WONT who ended sFU, all patients were Binet stage A without del(11q), but patients who were at low risk had lower ALC, LDH, and beta-2-microglobulin levels, and were enriched for mutated IGHV status, as compared with patients who were at intermediate risk ending sFU (supplemental Table 1; P < .05).

Clinical outcomes. (A) Time to rereferral in patients ending sFU and (B) according to CLL-WONT risk. (C) TTFT in patients ending vs continuing sFU and (D) according to CLL-WONT risk. Pairwise log-rank tests indicated.

Clinical outcomes. (A) Time to rereferral in patients ending sFU and (B) according to CLL-WONT risk. (C) TTFT in patients ending vs continuing sFU and (D) according to CLL-WONT risk. Pairwise log-rank tests indicated.

Finally, we investigated the last known white blood count (WBC) at end of study follow-up. In patients ending sFU, the last WBC was similar between patients with CLL-WONT low and intermediate risk (17.3 × 109/L [IQR, 11.8-29.8] vs 17.6 × 109/L [IQR, 11.4-23.4], respectively; P = .61) indicating absence of peripheral blood CLL progression in this patient subpopulation. Among patients remaining alive and treatment-naïve, the median last WBC was 17.6 × 109/L (IQR, 11.6-29.7) and 40.1 × 109/L (IQR, 26.6-78.5) in patients ending and continuing sFU, respectively (P < .0001). Likewise, untreated patients who died (n = 29) had a median last known WBC of 15.9 × 109/L (IQR, 11.6-27.1) among patients ending sFU and 42.2 × 109/L (IQR, 24.5-61.8) among patients continuing sFU (P = .0057).

Discussion

Here, we report 3-year clinical outcomes in patients who were treatment-naïve and asymptomatic with low-to-intermediate risk CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT who ended or continued sFU. We report similar 3-year OS for patients ending and continuing sFU when stratifying patients based on CLL-WONT risk. Patients ending sFU had fewer hospital contacts, longer time to first infection, and shorter duration of in-hospital antimicrobial treatments. Finally, only 1 in 6 patients were rereferred to a hematological department within 3 years, and the 3-year TTFT rates were significantly lower for patients ending sFU than for those continuing sFU.

To our knowledge, this is the first study systematically ending sFU for CLL. Ending sFU was a nonrandomized intervention implemented by our department, allowing specialists to select patients with low-to-intermediate risk CLL-WONT to end sFU only in patients with early-stage CLL without meeting iwCLL criteria for treatment or needing supportive care. Because of this pragmatic clinical implementation, patients selected to end sFU also had lower CLL-WONT and lower CLL-IPI risk than patients selected to continue sFU, which have likely resulted in the significantly shorter TTFT in patients selected to continue sFU. Although the median time from CLL diagnosis to either ending or continuing sFU was several years and similar in both groups, we underscore that this observation time was not used for selecting patients to end or continue sFU. However, lymphocyte growth rates or slopes could in some instances have further informed physicians on the expected disease trajectory.16,17 Patients no longer followed by a specialist were also significantly older, whereas the fraction of patients ending and continuing sFU was fairly balanced. Patients followed by a specialist had regular out-patient visits and 24/7 access to hematological telephone counseling upon acute illness, whereas patients ending sFU would need to visit their general practitioner or contact their local emergency room for medical care afterhours. Because of this selection bias but fairly equal health care accessibility, clinical outcomes could be expected to favor patients ending sFU.

Demonstrating similar survival in CLL-WONT low and intermediate patients with CLL ending or continuing sFU, we provide evidence that patients with CLL-WONT and CLL-IPI low-to-intermediate risk could safely end sFU in a public health system with general access to general practitioner care. Patients with CLL followed by a specialist have a high risk of severe infections with high morbidity and mortality.18 Here, we confirm that infections were still the most common cause of death both among patients ending and continuing sFU. We similarly report a noteworthy need for in-hospital antimicrobials in ∼40% of all included patients, but patients continuing sFU contracted more infections with need of significantly longer hospitalization. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because of the nonrandomized clinical selection of patients ending or continuing sFU, resulting in a higher rate of CLL treatment among patients continuing sFU. In the CLL12 study, however, similar rates of infection were reported for patients treated with ibrutinib as compared with the placebo/WW group.9 In this study, we demonstrated fewer in-hospital infections among patients ending sFU than those who continued follow-up with a specialist. Importantly, only 1 patient who ended sFU died (of sepsis) with COVID-19, likely as a result of less CLL treatment in this group of patients. We also observed longer time to first infection and shorter duration of in-hospital infections in patients ending specialized care than in patients continuing sFU. As expected, the number of hospital contacts was also significantly lower among patients ending sFU than among patients who continuing sFU, which may be influenced by the intervention in itself and fewer patients receiving CLL treatment. Data on visits to general practitioners were unavailable for this study. Indeed, only 3 patients were rereferred with progressive CLL and need of treatment, whereas another patient, who was rereferred, progressed to need of treatment within months. As a likely consequence of high lymphocyte counts, frequent symptoms, and increased health care utilizations, we observed a 3-year rereferral rate of 16%. Without comparable studies, it was not possible to assess the magnitude of the rereferral rate compared with other ways of managing low risk CLL. On the other hand, 5 in 6 patients no longer followed by a specialist remained without CLL progression after 3 years of follow-up, and of note, patients who remained alive and treatment-naïve had significantly lower WBC levels than patients who were treatment-naïve indicating that no patients had undetected CLL progression, whereas patients with symptomatic disease returned to specialized care for further monitoring and treatment.

The 3-year TTFT rate was 4% for patients ending sFU, which is similar to findings in other studies identifying patients at low risk of CLL treatment.3,11,19,20 Information on IPS-E was not available, and further studies will evaluate whether this score may be used or combined for similar purposes. Importantly, there was no indication (regarding WBCs) that patients ending sFU died of CLL without being rereferred. On the other hand, 23% of patients, who were at lower risk and continued sFU, had been treated after 3-years of follow-up, likely as a result of patient selection. This emphasizes the importance and necessity of clinical selection of patients for continued sFU on top of CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT risk assessment, which partly explains the difference in TTFT between patients ending and continuing sFU. We thus stress that algorithms, such as previously proposed with CLL-WONT should never stand alone, but may only guide clinical decisions.11 Accordingly, we observed similar TTFT among patients with low and intermediate risk CLL-WONT. Thus, we here prospectively validate CLL-WONT for all risk groups, although CLL-WONT did not prospectively differ in TTFT between low and intermediate risk (supplemental Figure 1), likely as a result of patient selection.

This study clearly has limitations that primarily include and relate to selection bias owing to the nonrandomized study design and the physicians’ decision to continue or end sFU. Although the 2 groups were fairly balanced, the cohort was intermediate sized causing some statically inconclusive results in subgroup analyses. Even so, we wonder whether a randomized clinical trial both ending sFU and at the same time gathering follow-up data could in fact be performed. Furthermore, longer follow-up is warranted to compare our results to others, although to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing evidence for patients ending sFU. Patients followed by a specialist also had higher treatment rates which may likely result in increased use of antibiotics and risk of surveillance bias. The risk of infections may also likely relate to the higher proportion of patients with intermediate risk CLL among patients continuing sFU.21 Finally, we suspect that implementation of CLL-WONT will be difficult in countries with health care utilizations covered primarily by private health insurance. However, for the prioritization of scarce health care resources, ending sFU in asymptomatic lower-risk CLL is feasible. In this situation, however, this study and CLL-WONT in-specific may still offer clinical guidance and evidence for shared decisions.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that more than half of patients who were treatment-naïve with both CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT low-to-intermediate risk may safely be selected to end sFU. Among patients selected to end sFU, we observed fewer hospital visits, fewer infections, and shorter duration of in-hospital infections without compromising OS as compared with patients who continued sFU. Furthermore, 5 out of 6 patients were not rereferred to a hematological department within 3 years. Importantly, these patients showed no signs of leukemic progression, whereas patients who were rereferred with a need of treatment also started timely treatment. For practical reasons, patients who may end sFU can be identified as having TP53 wild-type CLL with a CLL-IPI and CLL-WONT score of up to 3 points.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the research fund at the Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet.

Authorship

Contribution: C.B., L.K., and C.U.N. conceived the study; C.U.N., C.d.C.-B., and J.M. evaluated patients; C.B. and C.U.N. gathered the data and wrote the draft of the manuscript; C.B. performed the statistical analyses; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.B. has received travel grants from Octapharma outside this study. C.d.C.-B. has received honoraria from Octapharma. C.U.N. has received research funding and/or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Janssen, AbbVie, BeiGene, Genmab, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Takeda, and Novo Nordisk Foundation, and research funding from the Danish Cancer Society, Alfred Benzon Foundation, and the ERA PerMed EU program.

Correspondence: Carsten Utoft Niemann, Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet, Blegdamsvej 9, Building 7054, Copenhagen Ø 2100, Denmark; email: carsten.utoft.niemann@regionh.dk.

References

Author notes

Data may be shared on a collaborative basis via access to the Danish Lymphoid Cancer Research (DALY-CARE) data resource according to Danish and European Union health data privacy regulations upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, Carsten U. Niemann (carsten.utoft.niemann@regionh.dk).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.