Key Points

Differential expression of WNT ligands in patients with septic shock and a mouse model of endotoxemia correlates with inflammatory cytokines.

WNT ligands and WNT/β-catenin signaling positively regulate lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines without impairing IL-10.

Abstract

Improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying dysregulated inflammatory responses in severe infection and septic shock is urgently needed to improve patient management and identify new therapeutic opportunities. The WNT signaling pathway has been implicated as a novel constituent of the immune response to infection, but its contribution to the host response in septic shock is unknown. Although individual WNT proteins have been ascribed pro- or anti-inflammatory functions, their concerted contributions to inflammation in vivo remain to be clearly defined. Here we report differential expression of multiple WNT ligands in whole blood of patients with septic shock and reveal significant correlations with inflammatory cytokines. Systemic challenge of mice with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) similarly elicited differential expression of multiple WNT ligands with correlations between WNT and cytokine expression that partially overlap with the findings in human blood. Molecular regulators of WNT expression during microbial encounter in vivo are largely unexplored. Analyses in gene-deficient mice revealed differential contributions of Toll-like receptor signaling adaptors, a positive role for tumor necrosis factor, but a negative regulatory role for interleukin (IL)-12/23p40 in the LPS-induced expression of Wnt5b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt11. Pharmacologic targeting of bottlenecks of the WNT network, WNT acylation and β-catenin activity, diminished IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, and IL-12/23p40 in serum of LPS-challenged mice and cultured splenocytes, whereas IL-10 production remained largely unaffected. Taken together, our data support the conclusion that the concerted action of WNT proteins during severe infection and septic shock promotes inflammation, and that this is, at least in part, mediated by WNT/β-catenin signaling.

Introduction

Despite antibiotics, source control, and supportive therapies, the morbidity and mortality associated with sepsis remain high, causing an estimated 20 000 deaths per day worldwide.1-3 The pathology associated with severe manifestations of sepsis is precipitated by detrimental effects of the host response to infection. Molecular mechanisms underlying the dysregulated immune response in sepsis are the subject of intense investigation, which indicates an intricate interplay between microbial components, innate immune receptors, inflammatory cytokines, the coagulation system, and immune modulators.4 However, the failure of many clinical trials for adjunctive therapies for sepsis encourages reevaluation of the molecular drivers of sepsis-associated inflammation and pathology.5,6

WNT ligands are secreted glycoproteins with well-characterized functions during embryogenesis and tissue homeostasis, where they orchestrate cell proliferation and polarization.7 The 19 mammalian WNT ligands exhibit substantial conservation with regard to protein sequences and functions between humans and mice.8 Posttranslational modifications are required for activity of most mammalian WNT proteins. Acylation of conserved cysteine residues is mediated by the acyltransferase Porcupine (PORCN) in the endoplasmic reticulum. Acylated WNT ligands are transported and released aided by the chaperone Wntless.9 WNT ligands elicit intracellular signaling through cell surface receptors, including Frizzled 7-transmembrane receptors (FZD), low-density lipoprotein-related proteins, as well as receptor tyrosine kinases ROR and RYK.10 Depending on the receptor context, WNT ligands activate intracellular cascades that are broadly referred to as β-catenin-dependent and β-catenin-independent WNT signaling. The pool of cytoplasmic β-catenin is limited by action of a destruction complex consisting of scaffolding proteins (Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli), serine/threonine kinases (casein kinase [CK] 1α, glycogen synthase kinase 3β [GSK3β]), and protein phosphatase 2Α. β-catenin phosphorylation by CK1α and GSK3β destines it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. WNT interaction with FZD and low-density lipoprotein-related protein receptors inactivates the destruction complex and stabilizes cytoplasmic β-catenin. This enables nuclear translocation of β-catenin, where it acts as a transcriptional coactivator for TCF/LEF transcription factors, supported by coactivators such as CREB binding protein (CBP). WNT signaling events that occur independent of β-catenin include phospholipase C–driven Ca2+ mobilization, RAC1-mediated phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases, and RHOA/ROCK-driven rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton.10

Associations of elevated WNT expression and signaling activity with bacterial infections and chronic inflammatory disorders during the last decade have unveiled immune-related functions of WNT proteins.11-14 Studies in patients and animal models suggest WNT proteins shape inflammation and tissue repair.11,12,15-20 The current paradigm suggests WNT ligands exert pro-inflammatory or immune-modulatory functions, depending on whether they activate β-catenin-independent or β-catenin-dependent signaling. This model largely relies on studies using the prototypical WNT ligands WNT5A and WNT3A as triggers for β-catenin-independent and β-catenin-dependent signaling, respectively. For example, WNT5A expression by human macrophages is strongly elevated in response to mycobacterial infection and LPS stimulation, and is mediated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling.11 Exogenous addition of WNT5A to human macrophages induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, including interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1β, in the absence of further stimulation.12 In a dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis model in vivo, inducible conditional WNT5A knockout mice had lower pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (eg, Tnf, Il6, Il12b, Ifng) in colon tissue compared with wild-type mice.21 In contrast, exogenous WNT3A decreased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 expression by Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin–infected RAW264.7 cells, reduced TNF release from M tuberculosis–infected murine primary macrophages, and induced IL-10 and transforming growth factor β expression by M tuberculosis–infected dendritic cells.18,22,23 It is important to note that although recombinant WNT proteins are invaluable tools in many models, they may contain unrelated agonists for TLRs,24 which clouds the interpretation of studies using these protein preparations in TLR-bearing cells. Although an increasing number of in vitro studies affirm contributions of WNT proteins to cell-specific cytokine responses, there is limited understanding of how the concerted action of WNT proteins shapes inflammatory responses in vivo.

Previous studies have reported elevated WNT5A expression in serum of patients with sepsis12,25 and lung tissue of patients with sepsis-related acute respiratory distress syndrome.26 In the present study, we report differential expression of multiple WNT ligands in blood of patients with septic shock compared with healthy controls. Our data reveal a cluster of WNT ligands whose expression directly correlates with inflammatory cytokine expression. Analyses in the mouse model of systemic endotoxemia similarly revealed correlations between WNT ligand expression and inflammatory cytokines, some of which mirrored the observations in patients with septic shock. We further demonstrate differential contributions of innate immune signaling modules, as well as inflammatory cytokines to WNT ligand expression in vivo, and indicate that the net contributions of both WNT ligands and β-catenin activity are pro-inflammatory during endotoxin-induced inflammation.

Methods

Human study subjects

Two milliliters blood were collected (PaxGene Blood RNA tubes, Applied Biosystems) from 23 patients with septic shock within 72 hours of diagnosis in a prospective, observational study at a tertiary referral intensive care unit,27 approved by the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Ethics Committee (HREC/11/QRBW/201). Patients or their next of kin provided informed consent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously published.27 Clinical patient management was at the discretion of the treating physician. Demographic data, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation Score (APACHE) II, and white blood cell differentials were recorded on study entry. Blood collection from healthy volunteers was approved by the ethics committees of the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (HREC/11/QRBW/201), Greenslopes Private Hospital (14/53), and the University of Queensland (2014001457). All study participants provided informed consent. Details for patients and healthy controls are in Tables 1 and 2.

Healthy controls and patients with septic shock

| . | Healthy controls . | Patients with septic shock . |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 23 |

| Male/female (%) | 9/12 (43/57) | 14/9 (61/39) |

| Age ± standard deviation (range) | 47.7 ± 12.3 (31-69) | 55.7 ± 13.4 (31-75) |

| APACHE II median (range) | N/A | 22 (9-32) |

| 28-d survival | N/A | 19 |

| Mechanical ventilation | N/A | 22 |

| . | Healthy controls . | Patients with septic shock . |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 23 |

| Male/female (%) | 9/12 (43/57) | 14/9 (61/39) |

| Age ± standard deviation (range) | 47.7 ± 12.3 (31-69) | 55.7 ± 13.4 (31-75) |

| APACHE II median (range) | N/A | 22 (9-32) |

| 28-d survival | N/A | 19 |

| Mechanical ventilation | N/A | 22 |

N/A, not applicable.

Means ± standard deviations of white blood cell counts in patients with septic shock (109/L)

| Cell type . | Mean ± standard deviation . |

|---|---|

| Total | 12.76 ± 5.52 |

| Neutrophils | 10.50 ± 5.11 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.23 ± 0.81 |

| Monocytes | 0.66 ± 0.45 |

| Eosinophils | 0.09 ± 0.14 |

| Basophils | 0.03 ± 0.07 |

| Cell type . | Mean ± standard deviation . |

|---|---|

| Total | 12.76 ± 5.52 |

| Neutrophils | 10.50 ± 5.11 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.23 ± 0.81 |

| Monocytes | 0.66 ± 0.45 |

| Eosinophils | 0.09 ± 0.14 |

| Basophils | 0.03 ± 0.07 |

Mice

Seven- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Australian Resource Centre), mice deficient in MYD88,28 TRIF,29 TNF,30 or IL-12p40,31 were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (Translational Research Institute, Queensland Institute for Medical Research Berghofer, Menzies Institute for Medical Research) and age- and sex-matched for experiments. All animal procedures adhered to the guidelines of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and were approved by the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee (567/09, 571/12, 554/15).

LPS in vivo challenge of mice

IWP-2 and ICG-001 (Tocris), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as control, were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline and injected at 20 mg/kg intraperitoneally 16 hours before intravenous LPS challenge (2 mg/kg in phosphate-buffered saline; 0111:B4 Escherichia coli, Sigma). Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation, and blood and organs were collected. Serum cytokine concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BD Biosciences).

Gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from human blood (Qiagen PaxGene Blood RNA isolation kit) and mouse tissue (RNAzol, Invitrogen). RNA was reverse transcribed (iScript, Biorad), followed by real-time quantitative PCR (ABI 7900HT, Perkin Elmer), using SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosciences) and gene-specific primers (supplemental Table 1). mRNA expression is represented as gene expression relative to hypoxanthine phospho-ribosyltransferase 1 (Hprt; 2[CtHprt- Ctgene]).

Mouse splenocyte culture

IWP-2 or ICG-001 (10 μM) or DMSO was added overnight to 1 × 106 splenocytes isolated from C57BL/6 mice. Cells were stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS or left unstimulated. Cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BD Biosciences). Brefeldin A was added before antibody staining for analysis of intracellular cytokine expression for which cells were blocked with anti-mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2) before addition of antibodies against mouse TCRβ (H57-597; BV421), CD11b (M1/70; PE). Intracellular staining (Cytofix/Cytoperm) was performed for F4/80 (BM8; FITC), TNF (MP6-XT22; APC), and IL-10 (JESS-16E3, PE). Samples were acquired on a Beckman Coulter Gallios and analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar, Inc.).

Statistical analyses

To assess differences between healthy controls and patients, gene expression was initially analyzed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov comparison (GraphPad Prism6), followed by analysis using R statistical software. To address potential convergence resulting from small numbers and enable ease of computation, data were scaled so that all quantities had a mean of zero. After adjusting for age, differences in gene expression between patients and controls were evaluated using linear univariate and multivariable regression. Bootstrap (“bootCase” function “car” package32 ) was used for an approximation of true confidence intervals. Changes of WNT and cytokine responses in mice or cell cultures were analyzed by 1- or 2-way ANOVA with Sidak or Dunnett multiple comparison corrections, as indicated in the figure legends. For comparisons of 2 groups, Mann-Whitney U test and Student t test were used (GraphPad Prism6). Pearson correlations were determined using the “cor” function of the R “stats” package33 and visualized using the “corrplot” package.34 P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Differential expression of WNT ligands in blood of patients with septic shock

We analyzed the expression of WNT ligands in whole blood of patients with septic shock admitted to intensive care and of healthy controls, and compared them with expression of key inflammatory cytokines. Of the 19 human WNT ligands, expression of 12 ligands was reliably detected in human blood. Expression of WNT5B and WNT11, as well as TNF and IL10, was elevated in the majority of patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 1A-B). In contrast, expression of IL6 and IFNG was diminished in the majority of patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 1C), which was also observed to varying degrees for WNT1, 2B, 3, 6, 7A, 9A, 10A, 10B, and 16 (Figure 1D). Expression of WNT5A has been extensively investigated in infectious and inflammatory settings, including 2 reports on elevated serum concentrations in patients with sepsis.12,25 We thus expected a similar pattern for whole-blood WNT5A expression. WNT5A was detectable in only 7 of 23 patients and 8 of 21 healthy controls with no significant differences between the 2 groups (Figure 1E). However, expression of WNT5A was very low, which we interpret as low abundance of this transcript in whole-blood RNA preparations. Expression of WNT2, 3A, 4, 7B, 8A, 8B, and 9B, as well as IL12B, was below the detection limit in most samples (data not shown). Considering the potential effect of age on the observed gene expression patterns, we found that mRNA expression of IL6, WNT9A, and WNT10B was inversely correlated to patient age. In contrast, there was no correlation between age and gene expression in healthy controls (supplemental Table 2).

Differential expression of WNT ligands and cytokines in whole blood of patients with septic shock. Gene expression was determined in whole blood, using quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and is depicted for each individual. Genes are grouped according to expression patterns compared with healthy controls. (A-B) Elevated or equivalent expression in the majority of patients. (C-D) Equivalent or diminished expression in the majority of patients. (E) No discernable difference between groups. Differences in the distribution of gene expression between healthy controls and patients with septic shock were determined by unpaired nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov comparison: *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .001; and regression analysis of means: #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .0001. Expression of the 7 WNT genes not depicted here was below the detection limit of the assay.

Differential expression of WNT ligands and cytokines in whole blood of patients with septic shock. Gene expression was determined in whole blood, using quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and is depicted for each individual. Genes are grouped according to expression patterns compared with healthy controls. (A-B) Elevated or equivalent expression in the majority of patients. (C-D) Equivalent or diminished expression in the majority of patients. (E) No discernable difference between groups. Differences in the distribution of gene expression between healthy controls and patients with septic shock were determined by unpaired nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov comparison: *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .001; and regression analysis of means: #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .0001. Expression of the 7 WNT genes not depicted here was below the detection limit of the assay.

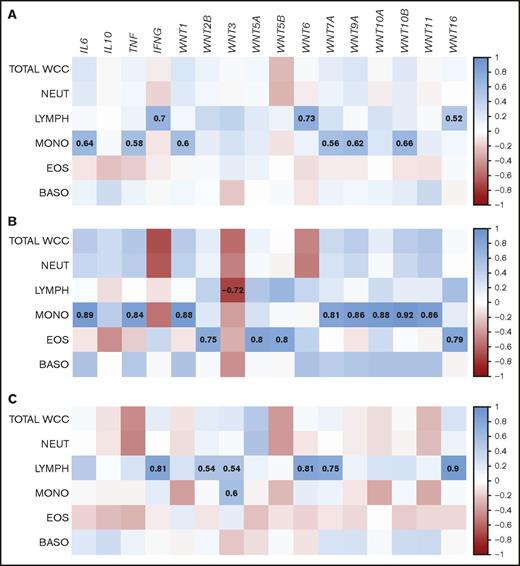

Septic shock can be accompanied by significant alterations in abundance and composition of blood leukocyte populations.35 Serum concentrations of WNT5A in patients with sepsis were correlated with total leukocyte counts.25 We thus assessed whether the whole-blood gene expression patterns in patients with septic shock were influenced by the abundance of leukocyte subsets. Across the patient population, there was a signature of cytokine and WNT ligand expression associated with monocytes (IL6, TNF, WNT1, WNT7A, WNT9A, WNT10B) and lymphocytes (IFNG, WNT6, WNT16; Figure 2A). Separation of the patients into age groups revealed that younger patients (35-50 years; n = 8) contributed the monocyte signature, whereas the lymphocyte signature was mainly attributable to individuals older than 50 years (n = 15) (Figure 2B-C). Taken together, our data show differential expression of a large subset of WNT ligands in whole blood of patients with septic shock, which may be to some extent defined by age-related characteristics of blood leukocyte populations.

Correlations of WNT gene expression with white blood cell composition in patients with septic shock follow age-related patterns. Whole-blood gene expression of (A) all patients with septic shock, or separated by age (B) 35-50 years or (C) >50 years, was correlated with white blood cell counts. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are highlighted. BASO, basophils; EOS, eosinophils; LYMPH, lymphocytes; MONO, monocytes; NEUT, neutrophils; WCC, white cell count.

Correlations of WNT gene expression with white blood cell composition in patients with septic shock follow age-related patterns. Whole-blood gene expression of (A) all patients with septic shock, or separated by age (B) 35-50 years or (C) >50 years, was correlated with white blood cell counts. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are highlighted. BASO, basophils; EOS, eosinophils; LYMPH, lymphocytes; MONO, monocytes; NEUT, neutrophils; WCC, white cell count.

Correlation of WNT and inflammatory cytokine expression in patients with septic shock

Inflammatory cytokines have been implicated as both drivers of WNT expression and targets of WNT-mediated regulation of cellular functions. In blood of healthy controls, expression of 5 WNT ligands was directly correlated with the expression of inflammatory cytokines: WNT9A and WNT16 correlated with IL6, WNT7A with TNF, WNT5B with IL10, and WNT10B with IFNG. Moreover, direct correlations between some members of the WNT family were observed (Figure 3A). Although most of the above-mentioned correlations were also present in patients with septic shock, there were many additional positive correlations between WNT ligands and cytokines, as well as among WNT ligands in patients with septic shock, than among healthy controls (Figure 3B). WNT1, WNT5B, WNT7A, WNT9A, WNT10A, WNT10B, and WNT11 showed significant direct correlation with the expression of IL6, TNF, and/or IL10, and there was significant correlation between the members of this cluster (Figure 3B). In contrast, WNT3 and WNT6 directly correlated with IFNG and each other, but with none of the WNT ligands associated with the IL6/TNF/IL10 cluster (Figure 3B). Expression of WNT2B, WNT5A, and WNT16 directly correlated with each other, but was independent of the analyzed inflammatory markers (Figure 3B). These data identify subsets of WNT ligands in patients with septic shock whose expression may be governed by distinct molecular mechanisms. Correlations of WNT expression with inflammatory cytokines suggest mechanisms of co-regulation and emphasize that WNT ligands are an integral part of the inflammatory response in septic shock.

Direct correlation of WNT ligand and inflammatory cytokine expression in patients with septic shock. Correlation of whole-blood gene expression of (A) healthy controls and (B) patients with septic shock. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are indicated.

Direct correlation of WNT ligand and inflammatory cytokine expression in patients with septic shock. Correlation of whole-blood gene expression of (A) healthy controls and (B) patients with septic shock. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are indicated.

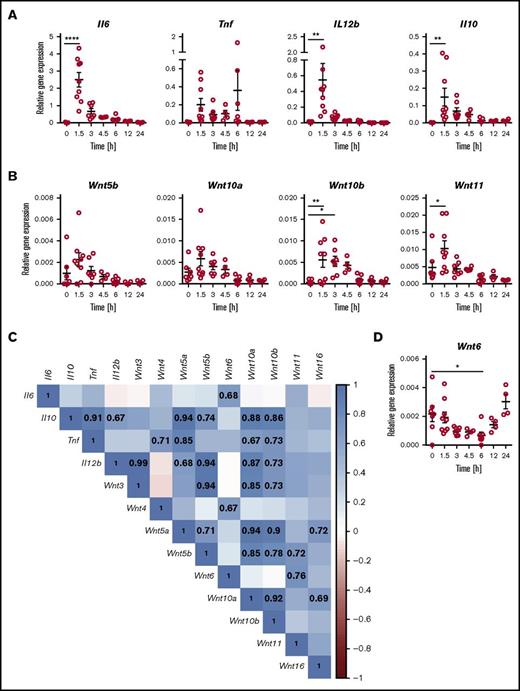

Dynamic regulation of WNT expression in the mouse model of endotoxemia-associated inflammation

In vivo model systems are invaluable to elucidate the contributions of WNT signaling to inflammatory responses in complex immune settings. With a focus on inflammatory cytokine responses, we chose the model of LPS-induced endotoxemia to investigate the cross-talk between WNT and cytokine signaling independent of the proposed impact of WNT signaling on the host’s antimicrobial defense.36

Systemic challenge of mice with LPS induced rapid elevation of Wnt5b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt11 mRNA expression in spleen tissue at 1.5 h postchallenge. This was followed by a gradual decline, with kinetics similar to the decline in inflammatory cytokines (Figure 4A-B). In contrast, Wnt6 expression was transiently downregulated (Figure 4D). No discernable patterns of differential expression were observed for Wnt3, Wnt4, Wnt5a, and Wnt16 (supplemental Figure 1). The WNT receptors Fzd1 and Fzd5 showed trends toward transient induction of mRNA expression at 1.5 h after LPS challenge, and Fzd7 and Fzd8 expression decreased, whereas Fzd3, Fzd6, Fzd9, and Fzd10 mRNA expression was not altered (supplemental Figure 1). Expression of WNT ligands and Fzd receptors not depicted in Figure 4 and supplemental Figure 1 was below the limit of detection in mouse spleen tissue. At 1.5 h after the LPS challenge, mRNA expression of β-catenin and the WNT/β-catenin target gene Wisp1 was significantly elevated. A similar pattern was observed for the WNT/β-catenin target gene Axin2 in some but not all mice (supplemental Figure 1). These data demonstrate dynamic regulation of the expression of multiple WNT ligands and receptors known to trigger β-catenin-dependent and β-catenin-independent WNT signaling, accompanied by indications of active WNT/β-catenin signaling.

Differential expression of WNT ligands and inflammatory cytokines in the mouse model of acute systemic endotoxemia. Mice were injected intravenously with LPS (2 mg/kg) and gene expression determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in spleen tissue at the indicated time points. Transient elevation of mRNA expression for (A) inflammatory cytokines and (B) WNT ligands; (D) transient downregulation of Wnt6 mRNA expression. Relative gene expression is depicted for individual mice analyzed cumulatively in 3 independent experiments; mean ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Groups were compared by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. *P < .05, **P < .01, n.s. not significant. (C) Positive correlation of WNT ligand and inflammatory cytokine expression in tissue of mice 1.5 h after LPS challenge. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are indicated. Expression of the 10 WNT genes not depicted in (C) was below the detection limit of the assay.

Differential expression of WNT ligands and inflammatory cytokines in the mouse model of acute systemic endotoxemia. Mice were injected intravenously with LPS (2 mg/kg) and gene expression determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in spleen tissue at the indicated time points. Transient elevation of mRNA expression for (A) inflammatory cytokines and (B) WNT ligands; (D) transient downregulation of Wnt6 mRNA expression. Relative gene expression is depicted for individual mice analyzed cumulatively in 3 independent experiments; mean ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Groups were compared by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. *P < .05, **P < .01, n.s. not significant. (C) Positive correlation of WNT ligand and inflammatory cytokine expression in tissue of mice 1.5 h after LPS challenge. Proximity of the correlation coefficients to 1 (direct correlation) and −1 (inverse correlation) is highlighted according to the depicted heat map scale. Correlation coefficients for correlations that meet statistical significance (P < .05) are indicated. Expression of the 10 WNT genes not depicted in (C) was below the detection limit of the assay.

Analogous to the comparison of healthy controls and patients with septic shock, there was a marked increase in direct correlations between WNT and cytokine expression in the spleen tissue of LPS-challenged mice (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 2). Similar to patients with septic shock, mRNA expression of Wnt10a and Wnt10b were positively correlated and were also directly correlated to Tnf and Il10 expression. Wnt5b expression was positively correlated to Il10 and Wnt11. Such similarities between mouse spleen tissue and blood of patients with septic shock suggests a degree of cross-species conservation in the responsiveness of WNT ligands to microbial challenge. However, there are many examples of differences in the correlations between WNT and cytokine gene expression between patients with septic shock and the mouse model of systemic endotoxemia (Figures 3B and 4C). This may reflect species- and tissue-specific host responses that are likely flavored by complex factors such as the nature of the microbial insult and timing of sampling.

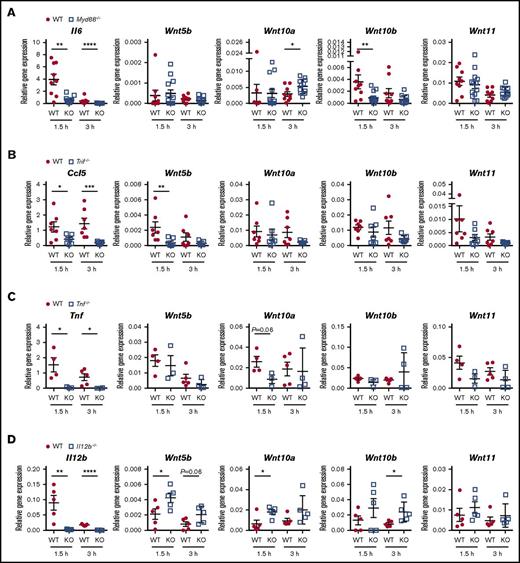

Differential roles of TLR signaling and inflammatory cytokines in LPS-induced WNT responses in vivo

TLR and cytokine signaling are implicated as regulators of WNT ligand expression in response to microbial encounter. Yet many of these conclusions are drawn from observations in in vitro systems. We next investigated the contributions of the TLR signaling adaptors, MYD88 and TRIF, as well as the inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-12/23p40, to LPS-induced WNT expression. Only expression of Wnt10b was diminished in Myd88−/− mice, similar to Il6 (Figure 5A), suggesting Wnt10b expression is positively regulated by TLR4-MYD88 signaling. In contrast, Wnt10a expression was elevated in Myd88−/− mice, suggesting a negative regulatory role for this signaling pathway. No significant differences between LPS-challenged WT and Myd88−/− mice were observed for Wnt5b, Wnt11 (Figure 5A), Wnt5a, or Wnt6 mRNA (supplemental Figure 3).

Multimodal regulation of LPS-induced WNT ligand expression by innate immune signaling pathways and inflammatory cytokines. Gene expression was determined in spleen tissue of mice injected with LPS (2 mg/kg) for 1.5 and 3 h. Mice deficient in TLR signaling adaptor proteins (A) MYD88 or (B) TRIF were compared with wild-type (WT) controls at each time point by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. Values for individual mice analyzed in 3 independent experiments are depicted, and mean ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Mice deficient in the inflammatory cytokines (C) TNF and (D) IL-12/IL-23p40 were compared with WT controls in 2 independent experiments. Gene expression for individual mice is depicted, and means ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Groups were compared by 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001, n.s. not significant. KO, knockout.

Multimodal regulation of LPS-induced WNT ligand expression by innate immune signaling pathways and inflammatory cytokines. Gene expression was determined in spleen tissue of mice injected with LPS (2 mg/kg) for 1.5 and 3 h. Mice deficient in TLR signaling adaptor proteins (A) MYD88 or (B) TRIF were compared with wild-type (WT) controls at each time point by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. Values for individual mice analyzed in 3 independent experiments are depicted, and mean ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Mice deficient in the inflammatory cytokines (C) TNF and (D) IL-12/IL-23p40 were compared with WT controls in 2 independent experiments. Gene expression for individual mice is depicted, and means ± standard error of the mean are indicated. Groups were compared by 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001, n.s. not significant. KO, knockout.

Trif−/− mice showed a significant reduction in the LPS-induced Wnt5b expression, similar to the effect on Ccl5 (Figure 5B). In contrast, expression of Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt11 was comparable between WT and Trif−/− mice (Figure 5B). Although LPS did not enhance expression of Wnt5a and Wnt6 in spleen tissue, expression of these genes was diminished in Trif−/− mice compared with WT controls (supplemental Figure 3). This was observed in LPS- as well as mock-treated mice, suggesting a homeostatic role for TRIF signaling in the mRNA expression of Wnt5a and Wnt6. In contrast, expression of Wnt5b,Wnt10a,Wnt10b, and Wnt11 was comparable between mock-treated WT and Trif−/− mice (not depicted). Together, these data suggest that in vivo, there is no uniform dependency of WNT expression on TLR4 signaling modes, and that individual WNT ligands are regulated, directly or indirectly, by TLR4-MYD88 and TLR4-TRIF signaling.

Tnf−/− mice displayed somewhat reduced Wnt10a and Wnt11 expression, suggesting TNF enhances their expression during LPS challenge (Figure 5C). As Tnf−/− mice did not phenocopy Myd88−/− and Trif−/− mice, it appears that, at the time points investigated here, TNF contributes to LPS-induced elevation of Wnt10a and Wnt11 mRNA expression in spleen tissue, independent of MYD88 and TRIF. Spleen tissue of LPS-challenged Il12b−/− mice exhibited elevated expression of Wnt5b, Wnt10a, and Wnt10b (Figure 5D), suggesting that in mice, IL-12/23p40 impairs LPS-induced expression of these WNT ligands. Taken together, these data demonstrate varying contributions of TLR4 signaling pathways and inflammatory cytokines to LPS-induced WNT expression and reveal complex molecular cross-talk between innate immune receptors, WNT ligands, and inflammatory cytokines in vivo.

Inhibitors of WNT acylation and β-catenin activity dampen LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine responses

The majority of studies underpinning the current model of dichotomous WNT functions during inflammation used in vitro systems, exogenously added WNT proteins, and association studies in patient samples and animal models. Insights into the roles of WNT proteins to inflammatory responses in in vivo settings are emerging19,21 and are invaluable to determine how WNT signaling shapes immune responses. We next employed well-established small molecule inhibitors of WNT secretion and β-catenin activity to assess the net contributions of endogenous WNT proteins and β-catenin activity to LPS-induced inflammatory responses in vivo.

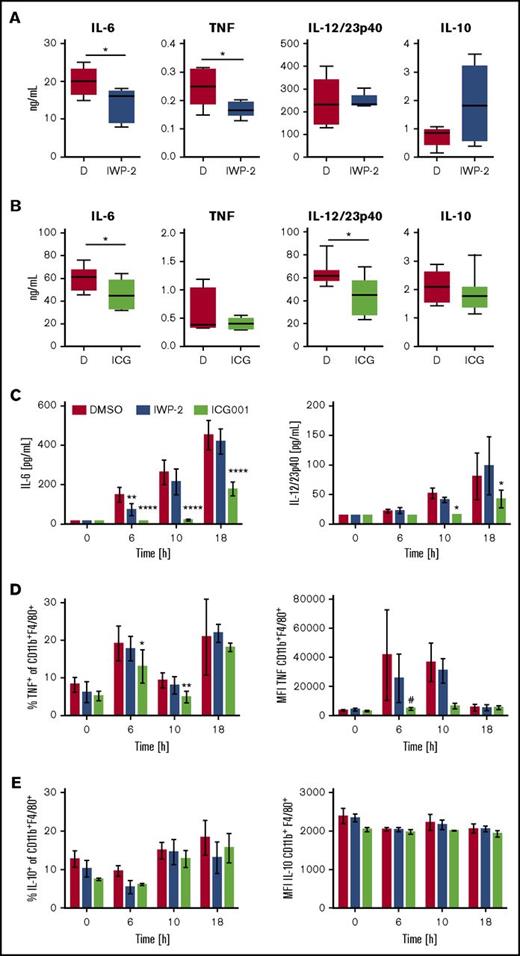

The small molecule IWP-2 inhibits WNT acylation by PORCN, thus impairing release from secreting cells.37 In LPS-challenged mice, IWP-2 significantly reduced serum concentrations of IL-6 and TNF, but not IL-12p40 (Figure 6A). IWP-2 also transiently reduced IL-6, but not IL-12p40, concentrations in LPS-stimulated splenocyte cultures in vitro (Figure 6C). Mice treated with ICG-001, an inhibitor of β-catenin interactions with CBP,38 displayed reduced serum concentrations of IL-6 and IL-12p40, and a trend toward reduced TNF concentrations (Figure 6B). ICG-001 had no significant effects on the expression of WNT ligands in response to LPS challenge (supplemental Figure 4), suggesting the inhibitory effect of ICG-001 on cytokine responses was not mediated by a shift in the WNT profile. ICG-001 also diminished IL-6 and IL-12p40 production by LPS-stimulated splenocytes in vitro (Figure 6C). Furthermore, ICG-001 impaired LPS-induced TNF protein expression by CD11b+ F4/80+ splenic macrophages, whereas no significant effects were observed in IWP-2-treated cells (Figure 6D). It was noteworthy that whereas pro-inflammatory cytokine responses were significantly reduced by IWP-2 and ICG-001, LPS-induced protein expression of IL-10 remained largely unaffected (Figure 6A-B,E).

Inhibitors of WNT production and β-catenin activity impair LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. WT mice received IWP-2 (targets the acyltransferase Porcupine) or ICG-001 (disrupts interaction of β-catenin with CBP) at 20 mg/kg, or DMSO as solvent control, 16 hours before challenge with LPS (2 mg/kg). Serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (A) in IWP-2 and (B) ICG-001–treated mice at 3 and 1.5 h after LPS challenge, respectively. Data in (A) are from 5 mice per condition analyzed in 2 independent experiments; data in (B) are from 7 mice per group analyzed in 3 independent experiments. Bars with medians represent the 25th and 75th percentile; whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare DMSO and inhibitor-treated groups. *P < .05. (C) Mouse splenocyte cultures were stimulated with LPS (1 µg/mL) for the times indicated in the presence or absence of IWP-2 or ICG-001 (10 µM), or DMSO. IL-6 and IL-12/23p40 concentrations in supernatants were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Because TNF and IL-10 concentrations in splenocyte culture supernatants were close to or below the detection limit of the assay (not shown), intracellular (D) TNF and (E) IL-10 expression by CD11b+F4/80hi cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. Data are means ± standard error of the mean of cultures from 4 (C) and 3 (D-E) individual mice analyzed in 2 independent experiments. Groups were compared by 2-way ANOVA and Dunnett multiple comparison correction; #P = .053, *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

Inhibitors of WNT production and β-catenin activity impair LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. WT mice received IWP-2 (targets the acyltransferase Porcupine) or ICG-001 (disrupts interaction of β-catenin with CBP) at 20 mg/kg, or DMSO as solvent control, 16 hours before challenge with LPS (2 mg/kg). Serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (A) in IWP-2 and (B) ICG-001–treated mice at 3 and 1.5 h after LPS challenge, respectively. Data in (A) are from 5 mice per condition analyzed in 2 independent experiments; data in (B) are from 7 mice per group analyzed in 3 independent experiments. Bars with medians represent the 25th and 75th percentile; whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare DMSO and inhibitor-treated groups. *P < .05. (C) Mouse splenocyte cultures were stimulated with LPS (1 µg/mL) for the times indicated in the presence or absence of IWP-2 or ICG-001 (10 µM), or DMSO. IL-6 and IL-12/23p40 concentrations in supernatants were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Because TNF and IL-10 concentrations in splenocyte culture supernatants were close to or below the detection limit of the assay (not shown), intracellular (D) TNF and (E) IL-10 expression by CD11b+F4/80hi cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. Data are means ± standard error of the mean of cultures from 4 (C) and 3 (D-E) individual mice analyzed in 2 independent experiments. Groups were compared by 2-way ANOVA and Dunnett multiple comparison correction; #P = .053, *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

These observations strongly suggest that the concerted action of WNT ligands during acute systemic LPS challenge in the mouse model is pro-inflammatory and may be uncoupled from the IL-10 response. Importantly, these data indicate that, in contrast to the current paradigm, β-catenin activity exerts a net pro-inflammatory function in the mouse model of endotoxemia-associated inflammation.

Discussion

Many studies that have shaped our current understanding of WNT ligand contributions to inflammatory responses have focused on individual WNT ligands or receptors. The present study demonstrates that multiple WNT ligands are differentially expressed in response to a microbial insult or LPS in both humans and mice. This emphasizes the importance of determining the net contributions of WNT ligands to the host response in vivo. Our results strongly suggest that in the mouse model of LPS-induced endotoxemia, the net contribution of WNT proteins to systemic cytokine responses is pro-inflammatory. In contrast to the current paradigm of anti-inflammatory functions of WNT/β-catenin signaling in the context of microbial stimulation,39 our data indicate that β-catenin/CBP-interactions enhance LPS-driven pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in vivo. This supports the notion that WNT-mediated β-catenin activity may also exert pro-inflammatory effects.40

In addition to potential direct functions of WNT ligands in the augmentation of inflammatory cytokine responses, a recent report indicates that WISP1 (WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein), whose expression can be driven by WNT/β-catenin signaling,41 synergizes with LPS in the induction of TNF production by macrophages and may contribute to lung injury in a model of polymicrobial sepsis.42 WISP1 also enhances inflammatory cytokine responses and tissue damage in a model of liver ischemia-reperfusion injury.43 It remains to be determined whether WNT proteins drive WISP1 expression in these models and whether this requires β-catenin. However, β-catenin knock-down in a model of liver reperfusion injury enhanced tissue damage and TLR4-driven inflammation. This was associated with immune-modulatory effects on dendritic cells,44 which is more in line with the proposed anti-inflammatory functions of β-catenin. Thus, the contributions of β-catenin to inflammation and tissue pathology/repair require further detailed investigation. In this context, it is important to note that β-catenin stabilization is not exclusively triggered by WNT ligands and can be driven by hepatic growth factor and microbial ligands.39,45,46 Thus, combined approaches targeting both endogenous WNT ligands as well as β-catenin activity, as employed here, should deliver refined insights into the contributions of WNT ligands and β-catenin signaling to inflammation and tissue pathology in complex in vivo settings.

Molecular pathways that govern WNT expression in response to microbial and cytokine stimulation are incompletely understood. The kinetics of WNT expression in the mouse model described here, correlations of WNT expression with multiple inflammatory cytokines in both humans and mice, as well as the distinct WNT expression patterns in mice deficient for TLR signaling adaptors and pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggest that mechanisms of co- and/or cross-regulation exist. For example, NF-κB and MAP kinase driven pro-inflammatory cytokine expression is a central outcome of TLR-mediated cell activation. We were the first to implicate TLR and NF-κB signaling in the expression of WNT5A by human macrophages in response to LPS and mycobacterial infection.11 Subsequent studies have identified putative NF-κB binding sites in the WNT5A promoter and confirmed functional contributions of NF-κB, ERK1/2, and p38 MAP kinase activity to WNT5A promoter activity.47-49 Our data indicate that canonical TLR4 signaling events via MYD88 mediate Wnt10b mRNA expression in spleen tissue of LPS-challenged mice. This is concordant with a report that identified Wnt10b as a direct target gene of NF-κB in mice.50 High conservation between the human WNT10B and mouse Wnt10b genes, as well as prediction of NF-κB and AP-1 binding sites in both species,51 suggests cross-species conservation of molecular mechanisms that govern their expression.

It is important to note, however, that in contrast to human macrophages, LPS does not significantly induce Wnt5a expression in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages.52 This is consistent with the lack of increased Wnt5a expression in spleen tissue of LPS-challenged mice and lack of MyD88 contributions (supplemental Figures 1 and 3). Moreover, although Wnt6 expression was elevated in in vitro LPS-challenged mouse macrophages,52 our data indicate transient downregulation of splenic Wnt6 expression 6 hours after LPS challenge and equivalent Wnt6 mRNA expression in WT and Myd88−/− mice. These observations highlight that differences in WNT responses occur in complex tissue contexts and in isolated cells cultured in vitro.

A role for TRIF signaling in the expression of WNT ligands has not been described previously. Our data suggest that TRIF signaling contributes to LPS-driven Wnt5b expression, as well as homeostatic expression of Wnt5a and Wnt6 in mouse spleen tissue. It will be of great interest to determine the nature of endogenous signals driving TRIF-dependent basal WNT expression. One previous report showed TLR4- and TRIF-dependent induction of Wisp1 expression and WISP1-driven inflammation in a liver ischemia-reperfusion injury model.43 As we and others have implicated WNT proteins in the liver injury response,15,53,54 it will be informative to assess whether the effect of TRIF-deficiency on WISP1-driven liver inflammation is a consequence of impaired TRIF-mediated WNT ligand expression.

TNF and TNF family members regulate WNT expression in diverse cellular contexts.11,50,55 Our data suggest some contributions of TNF to the LPS-induced expression of Wnt10a and Wnt11 in mice. In contrast, a negative regulatory role of IL-12/23p40 on the expression of Wnt5b, Wnt10a, and Wnt10b (Figure 5D) was unexpected in light of the proposed positive feedback loop of β-catenin-independent WNT signaling on the IL-12/IFNγ axis.11,21 As p40-deficiency affects both IL-12 and IL-23 signaling, future studies will be needed to dissect individual contributions of these cytokines to WNT expression and elucidate whether there are species-specific differences between humans and mice. Taken together, these newly gained insights into the regulators of WNT expression suggest that the cellular and tissue context of WNT expression and species-specific molecular modes of WNT regulation shape the WNT response in complex immune settings.

Modulation of detrimental inflammation and stabilization of microvasculature integrity are a major focus in the search for new supportive therapies in sepsis. However, more than 70 clinical trials in the last 20 years have failed to deliver novel adjunct therapies. These included blockade of individual cytokines, administration of anti-inflammatory mediators, and inhibition of coagulation.5 Patient heterogeneity, for example, resulting from comorbidities or the microbial origin, is one of the most likely causes for the failure of many of these trials. A fundamental reassessment of the host response in sepsis will be required to overcome the fatal shortcomings in our ability to define and manage sepsis.5 PORCN activity and β-catenin/CBP interactions are attractive therapeutic targets for new cancer therapeutics.56,57 Rapidly accumulating evidence on the cross-talk between WNT and inflammatory signaling may invite speculations as to whether WNT signaling is a valid therapeutic target for intervention in infection and chronic inflammation. Our data suggest that inhibition of PORCN and β-catenin activity impair pro-inflammatory cytokine responses, but have limited effects on IL-10 in a mouse model. If confirmed in humans, this might offer attractive opportunities for tailored anti-inflammatory interventions. However, in contrast to mice, the human IL10 promoter contains TCF binding elements, and binding of β-catenin/TCF complexes has been demonstrated.58 Thus, direct regulation of IL-10 responses by WNT ligands in humans may occur, and the consequences for infection-associated inflammation will need to be carefully assessed.

In summary, our study demonstrates that multiple WNT ligands are part of the immune response during septic shock. Some conservation in the human and mouse response to acute microbial challenge exists. The data presented here allude to the complex interplay among the WNT signaling network, inflammatory cytokines, and innate immune signaling pathways in vivo. Elucidation of molecular mechanisms that govern WNT-mediated immune responses may reveal opportunities for selective manipulation of inflammation for therapeutic benefit. However, the complex functions of WNT proteins in tissue homeostasis, repair, and carcinogenesis require careful consideration before targeting this pathway in any disease. In vivo studies in animal models, as well as insights gained from ongoing clinical trials, will be invaluable in the assessment of the potential risks and benefits of WNT-targeted therapeutic intervention.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Li Zhang and Alicia Kang for technical assistance, and the animal facility at the Queensland Institute for Medical Research Berghofer for provision of Trif−/− mice. The authors are grateful to the patients and their families, as well as the healthy volunteers, for their contributions to this study.

This work was supported in part by grants by the Australian Infectious Diseases Research Centre (A.B., J.C., and B.V.) and the University of Queensland (A.B.). M.G.-A. was supported by the Chilean government postgraduate scholarship Becas Chile and a University of Queensland top-up Scholarship. H.B. is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Translating Research Into Practice Fellowship. A.B. was supported by Research Fellowships by the International Balzan Foundation and the University of Queensland.

Authorship

Contribution: M.G.-A., D.V., J.K., T.T.K.N., and A.B. conducted experiments and analyzed data; M.G.-A., D.V., J.K., T.T.K.N., H.K., B.V., J.C., and A.B. interpreted data; H.B., R.T., B.V., and J.C. collected blood samples and related clinical information; and A.B. conceived and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript with editorial contributions by all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Antje Blumenthal, The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, Translational Research Institute, 37 Kent St, Brisbane, QLD 4102, Australia; e-mail: a.blumenthal@uq.edu.au.