Key Points

Protein S anticoagulant cofactor sensitivity and PAR1 cleavage activity were assayed for 9 recombinant APC mutants.

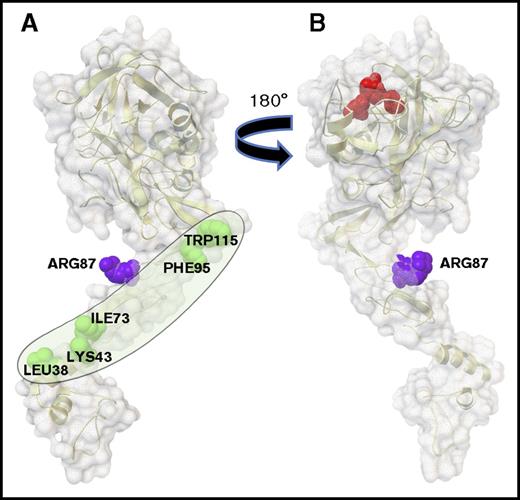

Residues L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115 on one face of the APC light chain define an extended surface containing the protein S binding site.

Introduction

Activated protein C (APC) possesses a spectrum of beneficial biologic activities in preclinical injury models, making it attractive for development of novel biologics.1 APC interacts with multiple substrates, cofactors, and cellular receptors, and understanding the structural basis for these interactions can enable engineering of APC mutants with functional selectivity for potential therapeutic indications (eg, for ischemic stroke).1-3 Mild deficiency of plasma protein S is linked to increased risk for venous thrombosis.4,5 Plasma protein S, a physiologic cofactor for APC’s anticoagulant activity, enhances proteolytic inactivation of factor Va (FVa) by binding to APC and altering its alignment with phospholipid membranes.6-11 APC mutagenesis studies showed that several residues, especially L38, in the γ-carboxyglutamic acid (GLA) domain is required for normal interactions with protein S.12-14 A major mechanism for APC’s cell signaling actions requires cleavage of protease activated receptor 1 (PAR-1).1,2 Here, we report functional interrogation of APC’s surface with the goal of identifying the extended protein S binding surface on APC.

Methods

FXa-1–stage clotting assay

Normal pooled plasma or protein S–depleted plasma was incubated for 180 seconds at 37°C with 80% phosphatidylcholine/20% phosphatidylserine vesicles (10 µM final), FXa (1.4 nM final), APC (0-20 nM final), and protein S (11 nM final) in 90 µL, and then clotting was initiated with addition of 50 µL containing 25 mM CaCl2. Each set of data were fitted with a linear regression curve, and the slope of each line was calculated using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The slopes obtained for each of the APC mutants were compared with the slope obtained with the wild-type (wt) APC. We arbitrary assigned the 100% value to the slope value of the wt-APC. See details in supplemental Methods.

PAR-1 cleavage assay

Analysis of PAR-1 cleavage at Arg46 by APC employed serum alkaline phosphatase (SEAP)–labeled PAR-1 cleavage assays, as described.15

Results and discussion

The anticoagulant activity of each APC variant was compared with that of wt-APC using FXa-1–stage plasma-based clotting assays in normal plasma and protein S–depleted plasma (Figure 1A). APC activity values were derived from variation of APC concentrations in the presence (normal plasma) and absence of protein S (protein S–depleted plasma) (see “Methods”). Compared with wt-APC, S11G/Q32E/N33D-APC (GED-APC) and E149A-APC showed greater sensitivity to protein S and much greater anticoagulant activity, as previously reported.12,16 Six APC variants showed reduced anticoagulant activity (Figure 1B). To clarify whether diminished interactions with protein S significantly contributed to loss of APC’s anticoagulant activity, clotting assays were made using protein S–depleted plasma containing increasing amounts of protein S (Figure 1C). These data for dose response to protein S show that single or multiple mutations at residues L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115 decreased the ability of protein S to enhance APC’s anticoagulant activity. Notably, the APC mutant in which all of these 5 residues were replaced (APC-del/5) lost >95% of protein S’s enhancement of APC activity.

Determination of protein S enhancement of anticoagulant activity of APC variants compared with wt-APC. (A) APC variants dose response prolongation of clotting time using normal human plasma (solid line) and protein S–depleted plasma (dashed line) in FXa-1–stage assays. wt-APC (●) was compared with GED-APC (▲) and APC-del/5 (□). (B) The anticoagulant activity of wt-APC and APC variants was determined in normal plasma (solid bars) and in protein S–depleted plasma (open bars) using FXa-1–stage assays where percent activity was calculated based on wt-APC having 100% activity. (C) The ability of protein S to enhance APC anticoagulant activity was studied using FXa-1–stage assays and using protein S–depleted plasma supplemented with varying concentrations of purified plasma-derived protein S. (D) Mutant APCs or wt-APC were incubated with wt-EPCR/SEAP-wt-PAR-1 cells or wt-EPCR/SEAP-R41Q-PAR-1 cells in Hanks balanced salt solution supplemented with 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.6 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. After 60 minutes, SEAP release was determined using 1-step p-nitrophenyl phosphate. After correction for background activity in the absence of protease, values were expressed as percentage of the total SEAP activity present on the cells.

Determination of protein S enhancement of anticoagulant activity of APC variants compared with wt-APC. (A) APC variants dose response prolongation of clotting time using normal human plasma (solid line) and protein S–depleted plasma (dashed line) in FXa-1–stage assays. wt-APC (●) was compared with GED-APC (▲) and APC-del/5 (□). (B) The anticoagulant activity of wt-APC and APC variants was determined in normal plasma (solid bars) and in protein S–depleted plasma (open bars) using FXa-1–stage assays where percent activity was calculated based on wt-APC having 100% activity. (C) The ability of protein S to enhance APC anticoagulant activity was studied using FXa-1–stage assays and using protein S–depleted plasma supplemented with varying concentrations of purified plasma-derived protein S. (D) Mutant APCs or wt-APC were incubated with wt-EPCR/SEAP-wt-PAR-1 cells or wt-EPCR/SEAP-R41Q-PAR-1 cells in Hanks balanced salt solution supplemented with 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.6 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. After 60 minutes, SEAP release was determined using 1-step p-nitrophenyl phosphate. After correction for background activity in the absence of protease, values were expressed as percentage of the total SEAP activity present on the cells.

Here mutagenesis studies of APC identified 5 of APC’s light chain residues that are required for normal enhancement of APC’s anticoagulant activity by protein S. When mapped on the surface of APC’s light chain, the 5 residues, L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115, delineate a hypothetic extended binding site for the protein S cofactor on 1 face (Figure 2A), which is on the opposite side of APC’s active site (Figure 2B), making this surface all the more reasonable as the protein S cofactor extended binding surface. The hypothetical protein S binding surface (Figure 2A) contains the β-hydroxy-Asp71 residue (not shown in the figure) whose mutation reduced APC anticoagulant activity.19 Moreover, this hypothetical protein S binding surface forms an obtuse angle in APC’s overall structure that could be altered by the binding of protein S to cause shortening the distance from APC’s active site to the phospholipid surface that binds the GLA domain.10,11 As mutations were accumulated in going from single to double to triple to quintuple mutations for the 5 residues (L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115), the loss of protein S cofactor activity increased progressively such that the quintuple APC mutant, APC-del/5, essentially lost all cofactor activity. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that each residue partially contributes to protein-protein interactions (ie, to protein S–APC interactions), thermodynamically independent of each another.20 No satisfactory method for measuring affinity of APC for protein S in the absence of other molecular components has been published, probably reflecting their low affinity in the absence of membranes or substrate. Our laboratory presented some data for a protein S domain binding to APC using fluorescence energy resonance transfer analysis for the binding of a synthetic EGF1 domain of protein S to APC in presence of phospholipid membranes, which is consistent with the concept that the EGF1 of protein S binds to the light chain of APC.11

The protein S binding site on APC. APC is depicted with its membrane-binding GLA domain on the bottom followed upward by EGF1, EGF2, and protease domains. (A) The gray oval outlines the protein S binding surface containing 5 labeled amino acid residues (green) whose mutations reduce protein S enhancement of APC’s anticoagulant activity. This surface is on the side opposite from the catalytic triad. (B) When the model in panel A is rotated 180 degrees, the active site triad is visualized on top in red; this surface in panel B lacks residues L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115. Surfaces show Arg87 (purple) whose mutation does not affect protein S cofactor activity. (Images were created using the Python Molecular Viewer v.1.5.6, and the molecular surface was computed using the Maximal Speed Molecular Surface program.17,18 )

The protein S binding site on APC. APC is depicted with its membrane-binding GLA domain on the bottom followed upward by EGF1, EGF2, and protease domains. (A) The gray oval outlines the protein S binding surface containing 5 labeled amino acid residues (green) whose mutations reduce protein S enhancement of APC’s anticoagulant activity. This surface is on the side opposite from the catalytic triad. (B) When the model in panel A is rotated 180 degrees, the active site triad is visualized on top in red; this surface in panel B lacks residues L38, K43, I73, F95, and W115. Surfaces show Arg87 (purple) whose mutation does not affect protein S cofactor activity. (Images were created using the Python Molecular Viewer v.1.5.6, and the molecular surface was computed using the Maximal Speed Molecular Surface program.17,18 )

APC has 2 distinct categories of bioactivities: anticoagulant, which reduces thrombotic risk, and cell signaling, which underlies multiple effects on cells.1,2 The beneficial effects from cell signaling often involve biased signaling consequent from APC’s cleavage of PAR-1 at Arg46.1,2,15,21 All the APC mutants had normal PAR-1 cleavage activity at R46 (Figure 1D). Translation from preclinical efficacy to clinical trials can be based on modulation of the activity profiles of different APC mutants,1-3,14,17,18,22,23 and in one example, this resulted in clinical trial of an APC mutant in for ischemic stroke.3,24 Delineation of the extended surface on APC that binds protein S sets the stage for extensive future development of APC mutants engineered to have greatly reduced anticoagulant activity while retaining normal PAR-1–dependent cell signaling activities.

In summary, we have delineated a hypothetical surface for binding of the anticoagulant cofactor, protein S, on an extended single face of APC’s light chain (Figure 2A), which will enable design and interpretation of a new generation of more selective APC variants with potential translational value because they are less capable of producing bleeding episodes while maintaining cellular protection.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL052246 [J.H.G.] and HL104165 [L.O.M.]) and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM096888-05) (M.F.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.F. and J.H.G. designed the study; J.A.F., X.X., and R.K.S. performed experiments; L.O.M. provided critical reagents and discussions; M.F.S. performed the analysis of molecular structure and preparation of graphics figure; and J.A.F. and J.H.G. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John H. Griffin, Scripps Research Institute, MEM-180, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Rd, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: jgriffin@scripps.edu.