Key Points

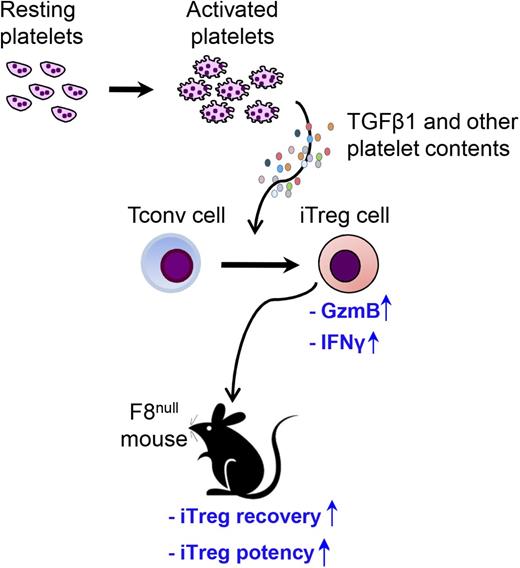

TGF-β1 from unfractionated pltLys can efficiently induce Treg cells.

The properties of Treg cells induced by TGF-β1 are altered by platelet contents.

Abstract

Platelets are a rich source of many cytokines and chemokines including transforming growth factor β 1 (TGF-β1). TGF-β1 is required to convert conventional CD4+ T (Tconv) cells into induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells that express the transcription factor Foxp3. Whether platelet contents will affect Treg cell properties has not been explored. In this study, we show that unfractionated platelet lysates (pltLys) containing TGF-β1 efficiently induced Foxp3 expression in Tconv cells. The common Treg cell surface phenotype and in vitro suppressive activity of unfractionated pltLys-iTreg cells were similar to those of iTreg cells generated using purified TGF-β1 (purTGFβ-iTreg) cells. However, there were substantial differences in gene expression between pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells, especially in granzyme B, interferon γ, and interleukin-2 (a 30.99-, 29.18-, and 17.94-fold difference, respectively) as determined by gene microarray analysis. In line with these gene signatures, we found that pltLys-iTreg cells improved cell recovery after transfer and immune suppressive function compared with purTGFβ-iTreg cells in factor VIII (FVIII)–deficient (F8null, hemophilia A model) mice after recombinant human FVIII (rhF8) infusion. Acute antibody-mediated platelet destruction in F8null mice followed by rhF8 infusion increased the number of Treg cells and suppressed the antibody response to rhF8. Consistent with these data, ex vivo proliferation of F8-specific Treg cells from platelet-depleted animals increased when restimulated with rhF8. Together, our data suggest that pltLys-iTreg cells may have advantages in emerging clinical applications and that platelet contents impact the properties of iTreg cells induced by TGF-β1.

Introduction

Apart from their fundamental role in hemostasis, platelets also modulate innate and adaptive immune responses.1-6 The mechanisms that underlie their immune modulatory activity are not fully understood. Platelet secretory granules contain a diverse array of bioactive proteins that mediate both physiologic and pathologic processes.7,8 Approximately 1011 newly produced platelets enter the blood stream daily replacing those that are aged or destroyed. Aged platelets undergo apoptosis and are phagocytosed by macrophages in the spleen and liver.9-11 Clearance of apoptotic platelets by phagocytes creates an immunoregulatory microenvironment via the production of regulatory cytokines, including transforming growth factor β 1 (TGF-β1) and interleukin-10 (IL-10), which support regulatory T (Treg) cell development and function.12-15

In previous studies, we demonstrated that ectopic expression of factor VIII (FVIII) or FIX in platelets resulted in the storage of FVIII or FIX in platelet α-granules and in the induction of antigen-specific immune tolerance in hemophilic mice.16-20 Although the precise mechanisms that mediate immune tolerance after platelet gene therapy are unclear, the process may be intrinsic to platelet contents, as platelet α-granules also contain abundant TGF-β1. Indeed the most prominent source of TGF-β1 in the body is platelets.21 The physiologic relevance of platelet-derived TGF-β1 (pltTGFβ) acting in support of immune tolerance is not fully understood and is complicated by other abundant cytokines and chemokines stored in platelet granules.5,22

There may be an important link between pltTGFβ, other platelet contents, and the properties of Treg cells. We hypothesize that pltTGFβ can induce conventional T (Tconv) cells to become functional induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells, and that other contents in platelets can impact the properties of Treg cells induced by pltTGFβ. In this study, we examined platelet lysates (pltLys) for their capacity to drive iTreg cell differentiation in vitro. We analyzed the gene signatures, the stability of Foxp3 expression, and the suppressive function of iTreg cells produced with pltLys. We also investigated the in vivo relevance of platelets and Treg cells along with their immune suppressive functions in hemophilia A (FVIII deficient, F8null) mice in response to recombinant FVIII (rhF8) infusion. Our data show important roles for pltTGFβ together with other platelet contents in altering gene expression signatures of Treg cells, promoting Treg cell stability, and enhancing antigen-specific Treg cell suppressive function.

Materials and methods

Mice

All animals were kept in pathogen-free microisolator cages at the animal facilities operated by the Medical College of Wisconsin. Isoflurane or ketamine was used for anesthesia. Animal studies were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. All mice were maintained under Specific Pathogen Free conditions, and both male and female mice were used in all experiments.

Antibodies

The detailed sources of antibodies used in this study are provided in the supplemental Materials.

In vitro iTreg cell induction

Foxp3EGFP mice23 in C57BL/6 (B6) background were used for in vitro iTreg conversion. The details are provided in the supplemental Materials. Platelets were isolated from wild-type C57BL/6 mice, and pltLys prepared by freeze/thaw were used as a source of pltTGFβ. The pltTGFβ was activated by transient acidification. To confirm that the induction of Treg cells by pltLys in vitro was dependent on TGF-β1, 10 μg/mL anti-TGF-β1 antibody was used to neutralize TGF-β1. iTreg cells were sorted for further studies as described subsequently.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single cell suspensions of leukocytes were stained for cell surface markers as described in our previous report.24 Natural Treg (nTreg) cells from Foxp3EGFP mice were used as a control. Intracellular Foxp3 staining was performed using the Mouse Regulatory T Cell Staining Kit following the protocol provided by the manufacturer (eBioscience). Cells were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with FlowJo software.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression profiles of iTreg cells were examined by microarray analysis as described previously.25,26 RNA was purified, and samples were labeled and hybridized to Mouse Genome 430 2.0 GeneChip. The details are provided in the supplemental Materials. Probe sets that exhibited a 1.4-fold difference (|log2 ratio| > 0.5) relative to Tconv cells were identified, and those that possessed a false discovery rate of <10% were used in subsequent analyses. The data files associated with this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus27 database (accession number GSE84225).

In vitro Treg cell suppression assay

The TGF-β1-containing unfractionated pltLys-iTreg or purified TGF-β1–iTreg (purTGFβ-iTreg) cells from in vitro cell culture were isolated by cell sorting and used to suppress CD4+ T-cell proliferation. The details are provided in the supplemental Materials. Suppression assays were analyzed using the Proliferation Platform in FlowJo software as reported.28 Division index was determined for each condition, and this number was used to calculate the percent of suppression.

In vivo Treg cell suppression

One million pltLys-iTreg or purTGFβ-iTreg cells were adoptively transferred by IV injection into F8null/B6 mice followed by rhF8 (Xyntha; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY) immunization weekly at 50 U/kg per week IV for a total of 4 weeks. One week after the last immunization, blood samples were collected. The titers of anti-FVIII inhibitory antibodies (inhibitors) and total anti-FVIII antibodies were determined by Bethesda assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), respectively, as described in our previous report.16,19 Six days after the iTreg cell transfer, CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood were analyzed by flow cytometry for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression to assess the recovery of the infused iTregs. CD45.1 and CD45.2 were used as congenic markers.

Platelet depletion

F8null animals were infused with anti-GPIb Ab (R300) at a dose of 2 mg/kg to deplete platelets followed by rhF8 immunization at a dose of 50 U/kg per week IV ×4. Normal immunoglobulin G (IgG) of the same isotype was used as a control in parallel experiments. Details are provided in the supplemental Materials. Splenocytes from animals 1 week after a single dose of platelet depletion followed by 1 dose of rhF8 immunization were restimulated in vitro using the T-cell proliferation assay as described subsequently.

T-cell proliferation

Spleens were isolated and dissociated to generate single cell suspensions. Splenocytes were labeled with CellTrace Violet and cultured with rhF8. Recombinant factor IX (rhF9) was used as an unrelated antigen control for T-cell proliferation. Details are provided in the supplemental Materials.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons of most data sets were evaluated by the unpaired Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the 3 groups. The incidence of anti-FVIII antibody development was compared using Fisher’s exact test. For all comparisons, a value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

pltLys induces naïve CD4+ T cells to express Foxp3

Platelet α-granules contain a number of cytokines and chemokines that are known to impact the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells, including TGF-β1, insulin-like growth factor 1,29 and platelet-derived growth factor.30 In order to evaluate the impact of platelet-derived TGF-β1 on iTreg differentiation in the context of the complex mixture of platelet content, we prepared pltLys by the freeze/thaw method. The level of total TGF-β1 in the lysate pool was 22.5 ± 3.7 ng/108 platelets (supplemental Figure 1) as determined by ELISA. We then added unfractionated pltLys to CD4+EGFP– T cells isolated by cell sorting from Foxp3EGFP mice in an iTreg cell induction assay. We compared the capacity of purTGFβ1 with the pltLys containing TGF-β1 to induce Foxp3 expression (Figure 1A). After culture for 72 hours with equivalent amounts of activated plt- and purTGFβ1, ∼90% of naïve CD4+ T cells expressed Foxp3, and there was no significant difference between the 2 TGF-β1 sources. When using pltLys, Foxp3 expression was completely abrogated by the addition of the anti-TGF-β1 antibody 1D11 (Figure 1A) and exhibited a dose-dependent relationship with the TGF-β1 (Figure 1B). Foxp3 induction using resting platelets or pltLys without activation of TGF-β1 resulted in low efficacy compared with activated TGF-β1 from lysates (supplemental Figure 2A-B). The Foxp3 induction from using the acidified pltLys that contained only 0.31 ng/mL of TGF-β1 showed similar efficacy to that obtained from unacidified pltLys containing 20 ng/mL of total TGF-β. These data indicate that other than TGF-β1, the cytokines contained in the pltLys have little impact on the induction of Foxp3 expression in vitro and that the majority of TGF-β1 in platelets is in an inactive form.

pltTGFβ induces Foxp3 expression and Treg cell differentiation in vitro. Both purTGFβ and pltTGFβ were activated by acidification before adding into tissue culture media. (A) Induction of Foxp3 expression in pltLys-induced cells. pltLys prepared from freeze/thaw were used as the source of pltTGFβ. Conventional CD4+Foxp3EGFP− cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and IL2 in the presence of 5 ng/mL pltTGFβ for 72 hours and analyzed for CD4+Foxp3EGFP+ expression by flow cytometry. PurTGFβ was used as a control in parallel. 1D11 (10 µg/mL) is an anti-TGF-β1 antibody that can inhibit TGF-β1 activity. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. Number in quadrant represents the average of 3 experiments. (B) The pltTGFβ dose response in Treg cell induction. Various doses of pltTGFβ (ng/mL) from pltLys were used to convert CD4+EGFP− T cells to CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. Number in quadrant represents the average of 5 experiments. (C) The cell phenotypes of CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced by pltTGFβ from pltLys. Flow cytometry analysis of CD25, CD62L, CD44, KLRG1, H57, GITR, PD1, and Helios. CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced by purTGFβ and nTreg cells from Foxp3EGFP mice were used as controls. Representative histograms from flow cytometry are shown. Histogram of pltLys-iTreg cells is shown in red, purTGFβ-iTreg cells in blue, and nTreg cells in gray. Experiments were repeated 3 times.

pltTGFβ induces Foxp3 expression and Treg cell differentiation in vitro. Both purTGFβ and pltTGFβ were activated by acidification before adding into tissue culture media. (A) Induction of Foxp3 expression in pltLys-induced cells. pltLys prepared from freeze/thaw were used as the source of pltTGFβ. Conventional CD4+Foxp3EGFP− cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and IL2 in the presence of 5 ng/mL pltTGFβ for 72 hours and analyzed for CD4+Foxp3EGFP+ expression by flow cytometry. PurTGFβ was used as a control in parallel. 1D11 (10 µg/mL) is an anti-TGF-β1 antibody that can inhibit TGF-β1 activity. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. Number in quadrant represents the average of 3 experiments. (B) The pltTGFβ dose response in Treg cell induction. Various doses of pltTGFβ (ng/mL) from pltLys were used to convert CD4+EGFP− T cells to CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. Number in quadrant represents the average of 5 experiments. (C) The cell phenotypes of CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced by pltTGFβ from pltLys. Flow cytometry analysis of CD25, CD62L, CD44, KLRG1, H57, GITR, PD1, and Helios. CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced by purTGFβ and nTreg cells from Foxp3EGFP mice were used as controls. Representative histograms from flow cytometry are shown. Histogram of pltLys-iTreg cells is shown in red, purTGFβ-iTreg cells in blue, and nTreg cells in gray. Experiments were repeated 3 times.

The cell phenotype and gene expression profiles of pltLys-iTreg cells

We used flow cytometry analysis to determine the phenotype of iTreg cells generated after a 72-hour culture with pltLys or purTGFβ. We examined the levels of several common proteins associated with Treg cell function and compared them with those seen in nTreg cells sorted from Foxp3EGFPmice. As shown in Figure 1C, the mean fluorescence intensity of CD25, CD44, GITR, and PD1 from iTreg cells induced by either pltLys or purTGFβ was greater than that observed for nTreg cells. The expression of H57 among the 3 groups was similar, whereas expression of Helios was seen only in the nTreg cell population.

In contrast, genome-wide RNA profiling revealed marked differences in gene expression signatures between pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells. As shown in Figure 2, in aggregate, there were 1646 probe sets that were differentially expressed relative to Tconv cells. Of these, 58% were common to both pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells, and 243 probe sets were unique to pltLys-iTreg and 444 to purTGFβ-iTreg cells. Relative to purTGFβ-iTreg cells, 37 gene transcripts showed a greater than threefold increased and 53 transcripts with a more than threefold reduced abundance in pltLys-iTreg cells. Of these 90 differentially expressed transcripts, granzyme B (Gzmb), interferon γ (Ifng), and Il2 were the most significantly different, showing 30-, 29-, and 18-fold more abundance, respectively, in pltLys-iTreg compared with purTGFβ-iTreg cells. The dominant up- or downregulated genes, which are known to regulate immune cell functions, are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2C-D. GzmB and IFN-γ protein expression were further analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 2E).

The microarray analysis of gene expression profile. RNA was purified from pltLys-iTreg, purTGFβ-iTreg, and Tconv cells. Samples were labeled and hybridized to Affymetric 430 2.0 GeneChips. Data are averaged from 3 arrays for each subset. Image data were analyzed with Affymetrix Expression Console software and normalized with Robust Multichip Analysis to determine signal log ratios. (A) Venn diagram showing commonly and uniquely regulated probe sets found in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells. Probe sets that revealed a 1.4-fold or greater difference (|log2 ratio| > 0.5) and ranked a product false discovery rate of <10% relative to Tconv cells are shown. (B) Heat map showing the fold change in expression of the 1646 differentially regulated probe sets identified in panel A. (C) Annotated heat map showing the expression levels of selected differentially regulated probe sets. For panels B and C, the scale (−4-fold to +4-fold). (D) Bar graphs compare the fold change in expression of select prototypical genes associated with immune functions in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of GzmB (left) and IFN-γ (right) expression in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells.

The microarray analysis of gene expression profile. RNA was purified from pltLys-iTreg, purTGFβ-iTreg, and Tconv cells. Samples were labeled and hybridized to Affymetric 430 2.0 GeneChips. Data are averaged from 3 arrays for each subset. Image data were analyzed with Affymetrix Expression Console software and normalized with Robust Multichip Analysis to determine signal log ratios. (A) Venn diagram showing commonly and uniquely regulated probe sets found in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells. Probe sets that revealed a 1.4-fold or greater difference (|log2 ratio| > 0.5) and ranked a product false discovery rate of <10% relative to Tconv cells are shown. (B) Heat map showing the fold change in expression of the 1646 differentially regulated probe sets identified in panel A. (C) Annotated heat map showing the expression levels of selected differentially regulated probe sets. For panels B and C, the scale (−4-fold to +4-fold). (D) Bar graphs compare the fold change in expression of select prototypical genes associated with immune functions in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of GzmB (left) and IFN-γ (right) expression in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells.

Dominant gene transcripts related to immune functions in pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells

| Molecule . | pltLys-iTreg/purTGFβ-iTreg (fold change) . | Functions . |

|---|---|---|

| Gzmb | 30.99 | Is important for CD8, natural killer T, and subsets of Treg cell function52 |

| Ifng | 29.18 | Plays a major role in immunosuppression mediated by IFN-γ–producing Tregs65 |

| Il2 | 17.94 | Essential for Treg cell function66 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (Ccl3) | 8.97 | Essential for regulation of Foxp3 stability67 |

| Fas ligand (Fasl) | 4.78 | Plays a critical role in cell-killing activity and enhances Treg cell suppressive activity68 |

| Neuritin 1 (Nrn1) | 4.51 | Is responsible for the persistence of Treg cells69 |

| Tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 14 (Tnfsf14) | 4.49 | Is important for Treg suppressive function70 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 (Nr4A2) | 4.06 | Plays important role in Treg cell development and suppressive functions71 |

| Thyroglobulin (Tg) | 4.03 | Regulates Treg cell function in preventing autoimmune thyroiditis72 |

| Cytotoxic and Treg cell molecule (Crtam) | 3.51 | Regulates CD8, natural killer, and Treg cell-killing functions73 |

| CD36 antigen (Cd36) | 3.47 | Plays a role in Treg induction74 |

| CD83 antigen (Cd83) | 3.24 | Involved in Treg suppressive function75 |

| CD40 antigen (Cd40) | −6.47 | Plays roles in Treg differentiation76 |

| Cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 2 β (Ctla2b) | −5.21 | Is one of the serine protease inhibitors77 |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 1 (Acsbg1) | −3.33 | Plays roles in T-cell demethylation (T helper 1 [Th1], Th17, Treg, etc)78 |

| Molecule . | pltLys-iTreg/purTGFβ-iTreg (fold change) . | Functions . |

|---|---|---|

| Gzmb | 30.99 | Is important for CD8, natural killer T, and subsets of Treg cell function52 |

| Ifng | 29.18 | Plays a major role in immunosuppression mediated by IFN-γ–producing Tregs65 |

| Il2 | 17.94 | Essential for Treg cell function66 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (Ccl3) | 8.97 | Essential for regulation of Foxp3 stability67 |

| Fas ligand (Fasl) | 4.78 | Plays a critical role in cell-killing activity and enhances Treg cell suppressive activity68 |

| Neuritin 1 (Nrn1) | 4.51 | Is responsible for the persistence of Treg cells69 |

| Tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 14 (Tnfsf14) | 4.49 | Is important for Treg suppressive function70 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 (Nr4A2) | 4.06 | Plays important role in Treg cell development and suppressive functions71 |

| Thyroglobulin (Tg) | 4.03 | Regulates Treg cell function in preventing autoimmune thyroiditis72 |

| Cytotoxic and Treg cell molecule (Crtam) | 3.51 | Regulates CD8, natural killer, and Treg cell-killing functions73 |

| CD36 antigen (Cd36) | 3.47 | Plays a role in Treg induction74 |

| CD83 antigen (Cd83) | 3.24 | Involved in Treg suppressive function75 |

| CD40 antigen (Cd40) | −6.47 | Plays roles in Treg differentiation76 |

| Cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 2 β (Ctla2b) | −5.21 | Is one of the serine protease inhibitors77 |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 1 (Acsbg1) | −3.33 | Plays roles in T-cell demethylation (T helper 1 [Th1], Th17, Treg, etc)78 |

The suppressive functions of pltLys-iTreg cells

Next, we compared the suppressive functions of iTreg cells induced by either pltLys or by purTGFβ. Sorted EGFP+ iTreg cells were cultured with effector T cells and their activity measured using an in vitro CD4+ T-cell suppression assay. Both purTGFβ-iTreg and pltLys-iTreg cells could suppress CD4+ T-cell proliferation in vitro, and there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. In both groups, the suppressive potency increased as the ratio of Treg cells to effector CD4+ T cells increased. At the lowest iTreg cell dose tested (1:8), CD4+ T-cell proliferation was suppressed by 15% (Figure 3A-B).

The suppressive function of pltLys-iTreg cells on T-cell proliferation in vitro. CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced in vitro by pltLys or purTGFβ were sorted and cocultured with violet-labeled CD4+ T cells (T effectors) at various ratios in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 72 hours. Cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 antibody. The daughter effector cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Suppression assays were analyzed using the Proliferation Platform in FlowJo software. Representative histograms from flow cytometry (A) and summarized data (B). Experiments were repeated 6 times. “DI” represents division index, which is the average number of cell divisions that a cell in the original population has undergone.

The suppressive function of pltLys-iTreg cells on T-cell proliferation in vitro. CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells induced in vitro by pltLys or purTGFβ were sorted and cocultured with violet-labeled CD4+ T cells (T effectors) at various ratios in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 72 hours. Cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 antibody. The daughter effector cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Suppression assays were analyzed using the Proliferation Platform in FlowJo software. Representative histograms from flow cytometry (A) and summarized data (B). Experiments were repeated 6 times. “DI” represents division index, which is the average number of cell divisions that a cell in the original population has undergone.

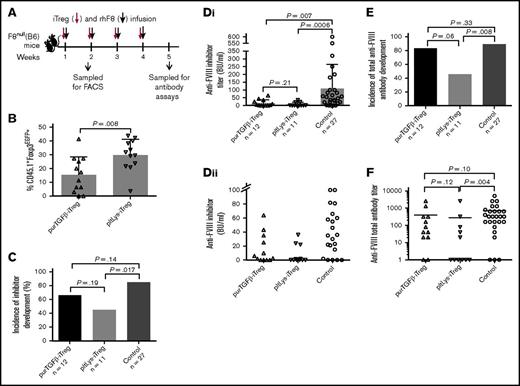

To compare the in vivo suppressive function and stability of Foxp3 expression of the 2 iTreg cell populations, we transferred 1 × 106 sorted CD45.1+EGFP+ iTreg cells generated with either purTGFβ or pltLys into CD45.2+ F8null mice followed by rhF8 immunization. Six days after the first iTreg cell transfer and rhF8 immunization, we determined the frequency of iTreg cells in the peripheral blood of the transfer recipients. In the group that received pltLys-iTreg cells, 29.8 ± 11.4% of CD45.1+ cells remained EGFP+, which was significantly higher than the group that received purTGFβ-iTreg cells (15.4 ± 13.1%; P = .008; Figure 4B).

The suppressive function of pltLys-iTregs in the immune response in vivo. One million CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells (iTregs/CD45.1+) induced in vitro by pltLys or purTGFβ were sorted and transfused into F8null/CD45.2+ mice followed by rhF8 immunizations. (A) Schematic diagram of iTreg cells and rhF8 transfusion in F8null(B6) mice. (B) Stability of Foxp3 expression on Treg cells induced by pltLys. Foxp3EGFP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry on peripheral CD45.1+CD4+ T cells 6 days after iTreg cell transfusion. (C) The incidence of anti-FVIII inhibitor development. Bars represent percentages. (Di) The titers of inhibitory antibodies in immunized F8null mice as determined by Bethesda assay. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparison. (Dii) The inhibitor titers in immunized F8null mice that are ≤100 BU/mL. This is a zoom-in look at the lower part of panel Di. (E) The incidence of total anti-FVIII antibody development. Bars represent percentages. (F) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in immunized F8null mice as determined by ELISA. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparison.

The suppressive function of pltLys-iTregs in the immune response in vivo. One million CD4+EGFP+ Treg cells (iTregs/CD45.1+) induced in vitro by pltLys or purTGFβ were sorted and transfused into F8null/CD45.2+ mice followed by rhF8 immunizations. (A) Schematic diagram of iTreg cells and rhF8 transfusion in F8null(B6) mice. (B) Stability of Foxp3 expression on Treg cells induced by pltLys. Foxp3EGFP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry on peripheral CD45.1+CD4+ T cells 6 days after iTreg cell transfusion. (C) The incidence of anti-FVIII inhibitor development. Bars represent percentages. (Di) The titers of inhibitory antibodies in immunized F8null mice as determined by Bethesda assay. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparison. (Dii) The inhibitor titers in immunized F8null mice that are ≤100 BU/mL. This is a zoom-in look at the lower part of panel Di. (E) The incidence of total anti-FVIII antibody development. Bars represent percentages. (F) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in immunized F8null mice as determined by ELISA. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparison.

One week after the fourth infusion of pltLys-iTreg cells and rhF8, 45.5% of animals developed anti-FVIII inhibitors and anti-FVIII antibodies. In contrast, in the group that received purTGFβ-iTreg cells and rhF8 infusions, 66.7% of mice developed inhibitors and 83.3% developed anti-FVIII antibodies. Without iTreg infusions, 85.2% of F8null control mice developed inhibitors and 88.9% developed anti-FVIII antibodies. These data show that the incidence of both inhibitor and anti-FVIII total antibody development in the pltLys-iTreg group, but not in the purTGFβ-iTreg group, was significantly lower (P = .017 and .008) than in the control group (Figure 4C-E). The inhibitor titers in groups that received either pltLys-iTreg or purTGFβ-iTreg cell transfusion were significantly lower than the titer in the control group that did not receive iTreg cell transfusion (P = .0006 and .007, respectively; Figure 4Di-ii). The inhibitor titer in the pltLys-iTreg group (7.8 ± 13.0 BU/mL) appeared lower than that in the purTGFβ-iTreg group (15.6 ± 21.4 BU/mL). In terms of total anti-FVIII antibodies, only the titer in the pltLys-iTreg group, but not in the purTGFβ-iTreg group, was significantly lower than in the control group (P = .004; Figure 4F). Together, these results demonstrate that the potency of iTreg cells derived from pltLys is greater in suppression of anti-FVIII immune responses in F8null mice, possibly because of improved stability of Foxp3 expression, other mechanisms that impact cell division or cell death, or both.

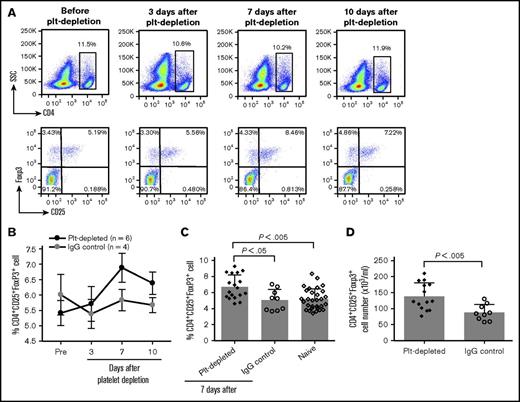

In vivo platelet destruction induces antigen-specific Treg cells

It has been shown that using anti-GPIb antibody R300 results in acute platelet depletion in circulation and clearance in spleen and liver.2 To investigate if there is a relationship between platelet contents and Treg cell properties in vivo, we used the anti-GPIb antibody to destruct platelets, releasing platelet contents locally in spleen in F8null mice, and subsequently analyzed Treg cells and anti-FVIII immune responses. As shown in supplemental Figure 3, 97% of TGF-β1 is stored in platelets, and only 3% distributed in plasma at steady state. When platelets were depleted using R300, the platelet number dropped 92% and the plasma TGF-β1 (pTGF-β1) level decreased 84%. As expected, both platelet number and pTGF-β1 levels were not affected in the group that received the IgG isotype control antibody. pTGF-β1 levels were restored as platelet number recovered, confirming that the level of pTGF-β1 is associated with the number of platelets.

As TGF-β1 signaling mediates both Treg cell homeostasis and the production of iTreg cells, we examined Treg cell numbers in peripheral blood after antibody-mediated platelet depletion followed by rhF8 immunization. We found that the frequency of Treg cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) increased with a peak at day 7 (Figure 5A-B). On day 7, the frequency of Treg cells was 6.7 ± 0.4%, which is significantly higher than in the IgG control group (5.1 ± 0.4%) and in the naïve F8null mice (5.2 ± 0.2%; Figure 5C). The total number of Treg cells in the peripheral blood of the platelet-depleted group was also significantly higher than in the IgG control group (Figure 5D).

Treg cell induction after depletion of platelets in vivo. F8null(B6/129S) mice were infused with anti-GPIb antibody (R300) or isotype IgG control (C301) followed by rhF8 immunization. Blood samples were collected from retro-orbital bleed, and blood cell counts were analyzed using the scil Vet ABC Hematology Analyzer. Treg cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots. CD4+ cells were gated for CD25+ and Foxp3+ analysis. (B) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells at various time points after platelet depletion and rhF8 immunization. (C) The frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood. (D) The number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood 1 week after platelet depletion.

Treg cell induction after depletion of platelets in vivo. F8null(B6/129S) mice were infused with anti-GPIb antibody (R300) or isotype IgG control (C301) followed by rhF8 immunization. Blood samples were collected from retro-orbital bleed, and blood cell counts were analyzed using the scil Vet ABC Hematology Analyzer. Treg cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots. CD4+ cells were gated for CD25+ and Foxp3+ analysis. (B) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells at various time points after platelet depletion and rhF8 immunization. (C) The frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood. (D) The number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood 1 week after platelet depletion.

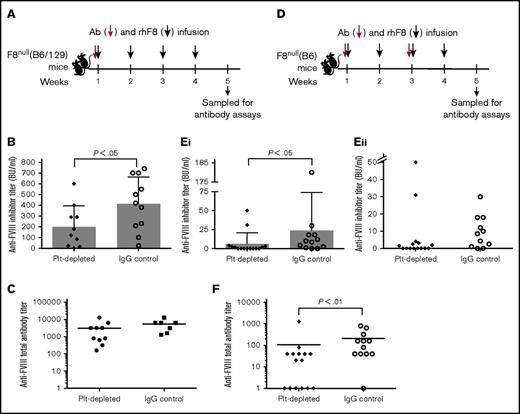

Because iTreg cell transfers reduce the incidence of inhibitor development and antibody-mediated platelet depletion increases the frequency and number of Treg cells, we measured the effect of platelet destruction on the anti-FVIII immune response. For these studies, we also used F8null mice from a mixed C57BL/6:129S (B6/129) genetic background, which is known to have a more robust anti-FVIII antibody response than is seen in F8nullmice on the B6 background.31,32 Our preliminary data showed that F8null(B6/129) mice died after a second platelet depletion plus rhF8 immunization even though the dose of the R300 anti-GPIb antibody was reduced to one-eighth with a 2-week interval. Thus, in F8null(B6/129) animals, platelets were depleted only once followed by 4 doses of rhF8 immunization. The titer of inhibitors, but not total anti-FVIII antibodies, in the platelet-depleted group was significantly lower than in the IgG control group (Figure 6B-C). When we assessed the impact of platelet depletion on the anti-F8 immune response in F8null(B6) mice, all animals that received rhF8 immunizations survived the full dose of the R300 antibody at the first week and the subsequent one-fourth dose at week 3. The titers of both inhibitors and total anti-FVIII antibodies in the platelet-depleted group were significantly lower than in the IgG control group (Figure 6E-F).

The titers of anti-FVIII antibodies in hemophilia A mice after platelet depletion followed by rhF8 immunizations. (A) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6/129S) mice. Ab, anti-GPIb antibody. Animals were infused IV with a single dose (2 mg/kg) of anti-GPIb antibody followed by 4 doses of rhF8 immunization (50 U/kg per week by IV injection). Isotype IgG was used in parallel as a control. (B) The inhibitor titers in F8null(B6/129S) mice. One week after the last immunization, anti-FVIII inhibitors were determined by Bethesda assay. (C) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in F8null(B6/129S) mice. One week after the last immunization, total anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA. (D) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6) mice. Anti-GPIb antibody was infused at the first week at a dose of 2 mg/kg and the third week at a quarter dose (0.5 mg/kg) followed by rhF8 immunizations (50 U/kg per week IV ×4). Isotype IgG was used in parallel as a control. (Ei) The inhibitor titers in F8null(B6) mice. One week after the last immunization, inhibitor titers were determined by Bethesda assay. (Eii) The titers of inhibitory antibodies in immunized F8null(B6) mice with inhibitors ≤50 BU/mL. This is a zoom-in look at the lower part of panel Ei. (F) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in F8null(B6) mice. One week after the last immunization, total anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA.

The titers of anti-FVIII antibodies in hemophilia A mice after platelet depletion followed by rhF8 immunizations. (A) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6/129S) mice. Ab, anti-GPIb antibody. Animals were infused IV with a single dose (2 mg/kg) of anti-GPIb antibody followed by 4 doses of rhF8 immunization (50 U/kg per week by IV injection). Isotype IgG was used in parallel as a control. (B) The inhibitor titers in F8null(B6/129S) mice. One week after the last immunization, anti-FVIII inhibitors were determined by Bethesda assay. (C) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in F8null(B6/129S) mice. One week after the last immunization, total anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA. (D) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6) mice. Anti-GPIb antibody was infused at the first week at a dose of 2 mg/kg and the third week at a quarter dose (0.5 mg/kg) followed by rhF8 immunizations (50 U/kg per week IV ×4). Isotype IgG was used in parallel as a control. (Ei) The inhibitor titers in F8null(B6) mice. One week after the last immunization, inhibitor titers were determined by Bethesda assay. (Eii) The titers of inhibitory antibodies in immunized F8null(B6) mice with inhibitors ≤50 BU/mL. This is a zoom-in look at the lower part of panel Ei. (F) The total anti-FVIII antibody titers in F8null(B6) mice. One week after the last immunization, total anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA.

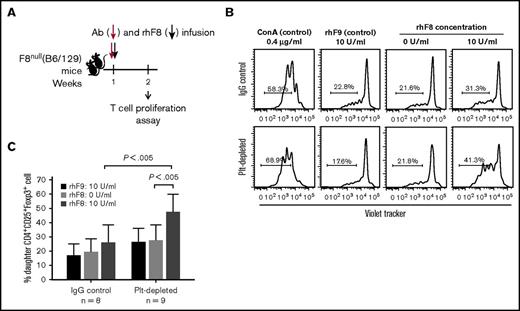

To explore the development of rhF8-Treg cell responses in platelet depleted animals, splenocytes were isolated from F8null(B6/129S) mice 1 week after a single dose of platelet depletion followed by 1 dose of rhF8 immunization and cultured for 96 hours with or without rhF8 restimulation. When splenocytes were restimulated with rhF8 in vitro, Treg cells proliferated significantly in contrast to those without rhF8 restimulation, or to those with the unrelated antigen rhF9 stimulation, or to those from IgG control mice (Figure 7B-C), but not CD4+Foxp3− T cells (data not shown). These data suggest that antigen-specific Treg cells developed after platelet depletion together with a single dose of rhF8 immunization.

Ex vivo T-cell proliferation assay assesses CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Treg cells in response to rhF8 restimulation. Splenocytes from F8null(B6/129S) mice after single dose of R300 and rhF8 infusion were labeled with CellTrace Violet and cultured with or without rhF8 for 96 hours. Recombinant factor IX (rhF9) was used as a nonrelevant antigen control. ConA was used as a positive control for T-cell proliferation assay. Isotype IgG-treated F8null mice were used as a control in parallel. Cells were stained for CD4, CD25, and Foxp3 and analyzed by flow cytometry for daughter cells. (A) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6/129S). (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms of Treg cell proliferation. (C) Treg cell proliferation graph.

Ex vivo T-cell proliferation assay assesses CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Treg cells in response to rhF8 restimulation. Splenocytes from F8null(B6/129S) mice after single dose of R300 and rhF8 infusion were labeled with CellTrace Violet and cultured with or without rhF8 for 96 hours. Recombinant factor IX (rhF9) was used as a nonrelevant antigen control. ConA was used as a positive control for T-cell proliferation assay. Isotype IgG-treated F8null mice were used as a control in parallel. Cells were stained for CD4, CD25, and Foxp3 and analyzed by flow cytometry for daughter cells. (A) Schematic diagram of platelet depletion and rhF8 infusion in F8null(B6/129S). (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms of Treg cell proliferation. (C) Treg cell proliferation graph.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that antigen-specific Treg cells increased after platelet depletion followed by rhF8 immunization in F8null mice and that the anti-FVIII immune response was suppressed.

Discussion

The central finding of this report is that TGF-β1 from platelets along with other platelet contents alters the gene expression profile of iTreg cells and augments the capacity of Treg cells to suppress anti-FVIII immune responses in hemophilia A mice. Unfractionated pltLys containing TGF-β1 can efficiently drive Tconv cells to express Foxp3 and become functional iTreg cells. In these pltLys-iTreg cells, the unique gene signatures are associated with greater stability and immunosuppressive function in vivo when compared with purTGFβ-iTreg cells. Immune responses that occur during and shortly after acute antibody-mediated platelet depletion are suppressed, which correlates with an increased frequency of Treg cells and the development of an antigen-specific Treg cell response. Together, these data suggest that platelet contents are critical in modulating Treg cell properties.

Our data support the emerging view that platelets and their granular contents play a fundamental role in innate and adaptive immune responses2-6 and complement other reports demonstrating that TGF-β1 maintains the suppressive function of Treg cells and is a critical mediator of iTreg cell induction.33 A study by Zhu et al34 demonstrated that platelets promote Treg cell responses. These investigators also showed that platelets augment and then suppress (biphasic regulation) Th1 and Th17 cell development via the TGF-β1 pathway when T cells were cocultured with platelets in vitro. Similar to the TGF-β1 from other cell sources,35 the majority of platelet-derived TGF-β1 is in a latent complex. We found that, without acidification, the bioactivity of pltTGFβ in Treg cell induction in vitro is only 1.6% of acidified pltTGFβ. However, after transient acidification, TGF-β1 in unfractionated pltLys has bioactivity comparable to that of acidified purTGFβ in terms of upregulating Foxp3 expression in Tconv cells activated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies in vitro. Although proteases, integrins, pH, and shear are factors that can activate TGF-β1 in vitro, the underlying mechanisms that activate TGF-β1 in vivo, however, are less well characterized.36-38 Platelets also contain other growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor 129 and platelet-derived growth factor,30 which may promote Treg cell proliferation. Our studies demonstrate that the in vitro bioactivity of pltLys in Treg cell induction was largely abrogated when neutralizing TGF-β1 antibody was present, confirming that TGF-β1 is the crucial cytokine in platelet content that induces Treg cells in our studies. However, our studies also showed that components of platelet granules other than TGF-β1 can alter gene expression and the immunosuppressive function of iTreg cells. Together, our data suggest that TGF-β1 from platelet granules acts in concert with other factors to promote the expression of many genes including Foxp3, Gzmb, Ifng, and Il2, resulting in the stable conversion of Tconv to iTreg cells.

Because Treg cells maintain dominant immune tolerance,39-45 it has long been appreciated that adoptive transfer of Treg cells may have clinical applications in preventing graft rejection in organ transplantation or in suppressing undesired immune responses.46,47 The pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells drive very similar profiles compared with Tconv cells. Both pltLys-iTreg and purTGFβ-iTreg cells had similar cell phenotypes and in vitro suppression in T-cell proliferation assay as shown in Figures 1C and 3. Although exhibiting concordance, they are distinct in potentially biologically relevant ways. Our studies demonstrated that pltLys-iTreg cells improved cell recovery after transfer and enhanced immune suppressive function compared with purTGFβ-iTreg cells in F8null mice after rhF8 immunization. Indeed, we observed that the percentage of Foxp3+ iTreg cells remained higher for pltLys-iTreg cells. In agreement with the improved recovery of pltLys-iTreg cells in vivo, only the animals that received pltLys-iTreg cell transfers had a significantly lower incidence of inhibitor and total antibody development and in anti-FVIII total antibody titers compared with the control group that did not receive iTreg cells. There was no statistical difference between animals treated with purTGFβ-iTreg cells and the control animals. These data suggest that pltLys-iTreg cells may provide a mechanism to enhance immunotherapy compared with purTGFβ-iTreg cells.

The mechanisms operative in pltLys that might improve the stability of Foxp3 expression and improve anti-FVIII immunosuppressive function over purTGFβ-iTreg cells in vivo could be because of the upregulation of Gzmb, Ifng, and other genes as listed in Table 1. GzmB has been shown to be involved in the suppressive function of Treg cells. Treg cells that kill activated T cells through a GzmB dependent mechanism have been described in both humans and mice.48-51 Treg cells also use GzmB to suppress antitumor responses.52 Treg subsets with specialized suppressive function mediated by coexpression of the canonical transcription factors associated with Th1 and Th2 polarization are essential for tolerance.53 For example, IFN-γ signaling in Treg cells induces T-bet, the canonical Th1 transcriptional regulator.54 Thus, our descriptive data are consistent with literature reports by others linking Treg-produced GzmB and IFN-γ and IFN-γR signaling to suppression by Treg subsets in vivo. Further characterization of plyLys-iTreg properties and identification of a specific component(s) from platelet contents that impacts the gene signature and the functions of iTreg cells is warranted.

Previous studies have demonstrated that platelet-derived TGF-β1 contributes to pTGF-β1 levels.21,35 Our studies using the acute platelet depletion confirm that the plasma level of TGF-β1 is regulated by platelets and suggest that the acute release of platelet contents can be applied to impact Treg differentiation. In our model, we observed an increase in the frequency and number of Treg cells 7 days after platelet depletion and rhF8 immunization. Different mechanisms may contribute to this increase. TGF-β1 from destructed platelets may induce Tconv cells to express Foxp3 in the spleen as Elzey et al have shown that platelets were cleared in spleen and liver when platelets were acutely depleted using anti-GPIb antibody.2 Thus, when the FVIII antigen is also present, the result would be an oligoclonal population of Treg cells that responds specifically to FVIII. Indeed, coupling protein to apoptotic cells can induce antigen-specific immune tolerance.55 Alternatively, platelet contents (including TGF-β1) may stimulate nTreg proliferation, leading to a broad Treg expansion that is polyclonal and not antigen specific. Our T-cell proliferation assays showed that Treg cells isolated from animals 1 week after a single platelet depletion followed by a single dose of rhF8 immunization proliferated when restimulated with rhF8 but did not respond to rhF9 compared with the unstimulated control. Thus, the data demonstrate that antigen-specific Treg cells were generated and possibly expanded by acute antibody-mediated platelet depletion.

Importantly, the acute platelet depletion model is different from immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in which platelets are chronically destructed rather than an acute event.56 As noted, numerical and functional deficiency of Treg cells has been described in patients with ITP and in mouse models of the disease.57-63 A firm role for TGF-β1 in maintaining peripheral Treg numbers and function has been established.64 The mechanisms that link the changes in pTGF-β1 levels seen in ITP and Treg deficiency remain unclear.56 For example, Treg deficiency might reflect the more chronic process of platelet depletion that results in low pTGF-β1 levels and reduced Treg homeostasis. Alternatively, acquired or genetic Treg deficiency may underlie the break in tolerance that culminates in ITP. Nevertheless, acute and chronic ITP in humans and chronic ITP in mice are associated with Treg deficiency.

In summary, our data demonstrate that pltLys can efficiently induce functional iTreg cells in vitro and that iTreg cells induced by pltLys have unique gene signatures and improved recovery, leading to greater immune suppressive function in F8null mice compared with those induced by purTGFβ. This implies that pltLys-iTreg cells may have advantages in emerging clinical applications utilizing iTreg cells. Acute destruction of platelets by antibody-mediated platelet depletion followed by rhF8 immunization can result in FVIII-specific Treg cell augmentation. Our data suggest that pltTGFβ together with other platelet contents may play important roles in Treg cell development in vivo. Our data also provide a potential mechanism for our observations19,20 that reconstitution of hemophilic mice with platelets that express and store FVIII or FIX together with other platelet contents in α-granules provokes FVIII- or FIX-specific immune tolerance.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Yan (Section of Quantitative Health Sciences, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin) for her assistant in statistical data analysis.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant HL-102035) (Q.S.) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants AI073731 and AI085090) (C.B.W.); Children’s Research Institute Pilot Grant (Q.S.); Bayer Hemophilia Award (Q.S.); and generous gifts from the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Foundation (Q.S.) and Midwest Athletes Against Childhood Cancer Fund (Q.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: D.H., X.L., and J.C. designed the study, performed experiments, and analyzed data; S.J. and L.S. analyzed data; J.A.S. performed experiments, analyzed data, and provided comments to the manuscript; H.W. contributed to conception of this study and made comments to the manuscript; M.J.H. contributed to the study design and made comments to the manuscript; R.H.A. contributed to study design; J.H. was X.L.’s PhD mentor; C.B.W. designed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and Q.S. designed and conducted research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Qizhen Shi, Section of Hematology/BMT/Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: qizhen.shi@bcw.edu; Calvin B. Williams, Section of Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, MFRC Room 5052, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: cwilliam@mcw.edu; and Jianda Hu, Department of Hematology, Union Hospital, No. 11 Xinquan Rd, Fuzhou, Fujian 350001, China; e-mail: jdhu@medmail.com.cn.

References

Author notes

D.H., X.L., and J.C. contributed equally to this study.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE84225).