TO THE EDITOR:

With over a decade of clinical experience using CD19–chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CD19–CAR-T) for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), toxicity syndromes have been well characterized. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and immune effector cell-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome have been established, each with respective grading systems that guide clinical management.1-14 The CD19–CAR-T registration trial (ELIANA) reported a 77% rate of overall CRS, 47% ≥grade 3 CRS, 40% overall neurotoxicity, and 13% ≥grade 3 neurotoxicity.15,16 Subsequent real-world CD19–CAR-T reporting describes lower toxicity rates with an overall CRS rate of 63%, ≥grade 3 CRS of 21%, overall neurotoxicity of 21%, and ≥grade 3 neurotoxicity of 7%,17 with the proposed rationale that patients in the real-world setting have lower disease burden. Whereas ELIANA had a 74% baseline median blast count and excluded patients with <5% blasts at enrollment, 87 (47%) pediatric patients treated with commercial CD19–CAR-T in the real-world setting had <5% blasts, of which 46 (25%) had no detectable disease at treatment.17 Higher baseline disease burden is associated with increased toxicity.2,8,13,18 As treatment paradigms shift toward treating patients with lower disease burden, reassessment of toxicity mitigation and monitoring practices is warranted, considering that strategies designed for patients with high burden (HB) disease may not apply to patients treated with low burden or no burden (LB) B-ALL.

Peak tisagenlecleucel expansion and inflammatory toxicities occur within the first 28 days post–CAR-T infusion.16 The tisagenlecleucel (CD19–CAR-T; Kymriah) package insert therefore guides that patients stay within 2 hours of the infusion center through 28 days19; many patients traveling to tertiary centers for CAR-T uproot to meet these proximity guidelines. This relocation associates with high socioeconomic burden. Parental occupation is often disrupted, and siblings are affected by separation from family or joining family and foregoing school attendance and routine.20 By redefining the toxicity window and relaxing hospital proximity guidelines for certain CAR-T recipients with LB B-ALL, the socioeconomic burden on patients and caregivers could be diminished.

Given that patients with LB B-ALL have improved CAR tolerability, we hypothesized that the risk window for CAR-T–mediated toxicities is <28 days in this patient subset. We evaluated the toxicity profile and risk window of tisagenlecleucel recipients with LB B-ALL in the real-world setting. Furthermore, we highlight that the time to peak toxicity following initial CRS or ICANS onset affords sufficient time for patients in this low-risk cohort to present for care.

We conducted a retrospective multisite (n = 15) study from the Pediatric Real-World CAR Consortium database to establish the timing of toxicity onset and resolution in pediatric tisagenlecleucel recipients with LB B-ALL (defined as <5% marrow blasts, ≤CNS2, and no extramedullary ALL). Institutions obtained independent institutional review board approval. Deidentified data were collected in a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant REDCap database. We report toxicity measures and duration descriptively. CRS was graded using American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus guidelines, whereas ICANS was graded per institutional standard.1

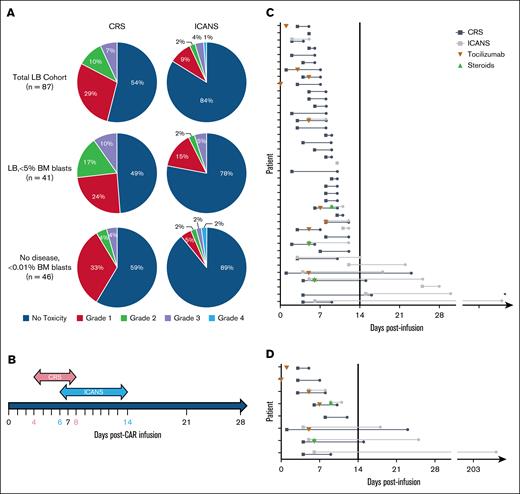

From August 2017 to March 2020, 87 tisagenlecleucel recipients (median age, 12 years, age range, 0-25 years) were reported to have LB B-ALL. Of these, 40 (46%) and 14 (16%) recipients had any degree of CRS and ICANS, respectively. However, only 6 (7%) and 4 (5%) recipients had ≥grade 3 CRS and ICANS, respectively. The median time of toxicity onset postinfusion was 4 days (range, 1-10 days) for CRS and 6 days for ICANS (range, 2-25 days), with a median duration of toxicity of 4 days (range, 1-22 days) and 7 days (range, 1-203 days) for CRS and ICANS, respectively, as shown in Figure 1.

Toxicity analysis of patients with LB B-ALL who received tisagenlecleucel. (A) Overall proportions of CRS and ICANS severity (no toxicity, grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4) among patients with LB B-ALL who received tisagenlecleucel in the entire cohort (row 1), then stratified by LB disease <5% marrow blasts (row 2) and no detectable disease (row 3). (B) Median toxicity duration of CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced any grade CRS (pink) and/or ICANS (blue) with median day of onset and offset indicated in pink and blue, respectively. (C) CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced any grade CRS (black line) and/or ICANS (gray line), with duration of toxicity in days. Patients who received tocilizumab (orange inverted triangle) with or without steroids (green triangle) are indicated on the day of first administration of each drug. (D) CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced ≥grade 3 CRS (black line) and/or ICANS (gray line), with duration of toxicity in days. Patients who received tocilizumab (orange inverted triangle) with or without steroids (green triangle) are indicated on the day of first administration of each drug. ∗Single outlier with prolonged neurotoxicity (209 days) due to persistent facial nerve palsy, despite resolution of acute toxicity and hospital discharge at day 17 post–CAR-T. BM, bone marrow.

Toxicity analysis of patients with LB B-ALL who received tisagenlecleucel. (A) Overall proportions of CRS and ICANS severity (no toxicity, grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4) among patients with LB B-ALL who received tisagenlecleucel in the entire cohort (row 1), then stratified by LB disease <5% marrow blasts (row 2) and no detectable disease (row 3). (B) Median toxicity duration of CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced any grade CRS (pink) and/or ICANS (blue) with median day of onset and offset indicated in pink and blue, respectively. (C) CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced any grade CRS (black line) and/or ICANS (gray line), with duration of toxicity in days. Patients who received tocilizumab (orange inverted triangle) with or without steroids (green triangle) are indicated on the day of first administration of each drug. (D) CD19–CAR-T cell recipients with LB B-ALL who experienced ≥grade 3 CRS (black line) and/or ICANS (gray line), with duration of toxicity in days. Patients who received tocilizumab (orange inverted triangle) with or without steroids (green triangle) are indicated on the day of first administration of each drug. ∗Single outlier with prolonged neurotoxicity (209 days) due to persistent facial nerve palsy, despite resolution of acute toxicity and hospital discharge at day 17 post–CAR-T. BM, bone marrow.

Of the patients with CRS and/or ICANS, 39 had complete data on toxicity onset/duration (evaluable). Of these, 38 (97%) patients had toxicity onset before day 14, as shown in Table 1. The single patient with late-onset isolated grade 1 ICANS at day 25 showed resolution without treatment in 3 days. The median time to peak C-reactive protein and ferritin was 7 and 9 days, respectively. Only 11 (28%) patients with CRS and/or ICANS required tocilizumab, and only 3 (8%) required steroids. There were no CRS grade 4 events, and only 1 grade 4 ICANS. The median time of toxicity resolution was 10 days post–CAR-T (range, 5-209 days) for overall toxicity (CRS, 8 days [range 4-23 days]; ICANS, 14 days [range, 5-209 days]). The outlier with prolonged ICANS had neurotoxicity beginning 6 days postinfusion followed by discharge at day 17, but right-side facial palsy persisted until day 209. Of the 5 (13%) patients with central nervous system (CNS)2 disease at preinfusion evaluation, only 2 (5%) experienced ICANS, both grade 1. By definition, no patients within the LB cohort had CNS3 disease at pre–CAR-T evaluation. Among the patients with LB, 52 (60%) received levetiracetam prophylaxis.

Patients with LB B-ALL analysis

| Acute toxicity analysis: CD19–CAR-T recipients with LB B-ALL . | |

|---|---|

| CRS (evaluable), n | LB 36∗ |

| Onset median, range | 4 d, 1-10 d |

| Duration of toxicity, median, range | 4 d, 1-22 d |

| Time to toxicity resolution from infusion, median, range | 8 d, 4-23 d |

| ICANS (evaluable), n | LB 13† |

| Onset, median, range | 6 d, 2-25 d |

| Duration of toxicity, median, range | 7 d, 1-203 d‡ |

| Time to toxicity resolution from infusion, median, range | 14 d, 5-209 d‡ |

| Location of infusion, n | LB 87 |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 47 (54) |

| Outpatient, n (%) | 40 (46) |

| Admissions, n | LB 87 |

| Duration of admission, median, range | 13 d, 1-46 d |

| PICU, n (%) | 15 (17) |

| Duration of PICU stay, median, range | 3 d, 1-16 d |

| Infused outpatient, required admission, n (%) | 18 (21) |

| Infused outpatient, no admission, n (%) | 22 (25) |

| Infused outpatient, required admission & PICU care, n (%) | 2 (2) |

| Acute toxicity analysis: CD19–CAR-T recipients with LB B-ALL . | |

|---|---|

| CRS (evaluable), n | LB 36∗ |

| Onset median, range | 4 d, 1-10 d |

| Duration of toxicity, median, range | 4 d, 1-22 d |

| Time to toxicity resolution from infusion, median, range | 8 d, 4-23 d |

| ICANS (evaluable), n | LB 13† |

| Onset, median, range | 6 d, 2-25 d |

| Duration of toxicity, median, range | 7 d, 1-203 d‡ |

| Time to toxicity resolution from infusion, median, range | 14 d, 5-209 d‡ |

| Location of infusion, n | LB 87 |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 47 (54) |

| Outpatient, n (%) | 40 (46) |

| Admissions, n | LB 87 |

| Duration of admission, median, range | 13 d, 1-46 d |

| PICU, n (%) | 15 (17) |

| Duration of PICU stay, median, range | 3 d, 1-16 d |

| Infused outpatient, required admission, n (%) | 18 (21) |

| Infused outpatient, no admission, n (%) | 22 (25) |

| Infused outpatient, required admission & PICU care, n (%) | 2 (2) |

PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Three patients had incomplete data on CRS toxicity duration.

One patient had incomplete data on ICANS toxicity duration.

Single outlier with prolonged neurotoxicity (209 days) due to persistent facial nerve palsy, despite resolution of acute toxicity and hospital discharge at day 17 post–CAR-T.

Among 83 evaluable patients with LB with complete data on toxicity onset and duration, 77 (93%) had no toxicity or complete resolution of toxicity before day 14 post–CAR-T. All 8 patients with ≥grade 3 CRS or ICANS had toxicity onset before day 14 (Figure 1).

The analysis of CD19–CAR-T recipients with HB B-ALL (≥5% marrow lymphoblasts, CNS3, and/or extramedullary disease) demonstrated overall higher toxicity, as previously established.17 Of the 93 patients with HB B-ALL, 74 (80%) had any grade CRS and/or ICANS, and 32 (34%) had ≥grade 3. Across all patients with HB with any grade toxicity, median onset for both CRS and ICANS was before day 14 (CRS: median, 5 days; range, 0-14 days; ICANS: median, 6 days; range, 1-14 days). Of 74 patients with HB with any grade toxicity, 35 (47%) had ongoing toxicity after day 14 (n = 22), disease progression within 28 days (n = 8), or death before day 28 (n = 5). Therefore, we restrict our recommendations to patients with LB B-ALL.

This real-world CAR-T analysis of patients with LB B-ALL shows that patients with low-burden or no burden disease at the time of CAR-T–infusion are at low risk of developing late-onset or severe CAR-mediated toxicity and should not be held to the conservative toxicity monitoring strategies for patients with HB B-ALL. We report that 97% of patients with toxicity declared themselves before day 14, and all but 6 patients had complete resolution before day 14. One patient with isolated late-onset ICANS at day 25 remained grade 1 and self-resolved. Therefore, we propose redefining the post–CAR-T toxicity risk window for patients with LB B-ALL and liberalizing existing guidelines to ensure patients with LB are not required to stay within a 2-hour distance of the treatment center for the full 28 days post–CAR-T.

We additionally note that patients do not generally present with post–CAR-T toxicities in peak form.21,22 Most commonly, patients initially present with fever, which subsequently increases in frequency and severity over time.21,22 In this LB cohort, median toxicity onset was at day 4 for CRS and at day 6 for ICANS, whereas median inflammatory markers did not peak until day 7 for C-reactive protein and day 9 for ferritin. This finding suggests an ample window between initial fever and toxicity escalation, allowing patients time to present to the hospital for management. We propose that patients with LB with no CRS and/or ICANS as well as those with resolved ≤grade 2 toxicity by day 14 may return home with a well-defined action plan including ready access to tocilizumab, reliable transportation, structured outpatient monitoring protocols, and clear escalation pathways for hospital admission in case of fever or other signs of toxicities. By relaxing this requirement, the socioeconomic burden that patients and families experience during this high-stress time may be offset with an earlier return home. Although we report on CRS and ICANS, the emergence of newer toxicity syndromes emerge (eg, hematologic toxicities, infection, and immune effector cell-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome) necessitates the inclusion of appropriate support and surveillance. As practice changes are implemented, patient-reported outcomes should be evaluated to capture impact on socioeconomic burden and quality-of-life post–CAR-T.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Anika Lagto, Casey Carr, Sharon Mavroukakis, Emily Egeler, and Joshua Murphy for their contributions to this work.

This work was supported by the Association of Auxiliaries for Children (L.S.). The Stanford REDCap platform (http://redcap.stanford.edu) is developed and operated by Stanford Medicine Research Technology team. The REDCap platform services at Stanford are subsidized by Stanford School of Medicine Research Office and the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant UL1 TR001085.

Contribution: L.E.A. and L.M.S. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; C.B. analyzed the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript; and K.N., S.P., H.P., S.J., V.A.F., C.L.P., J.R., J.-A.T., A.M., R.P., S.H.C.B., M.R.V., E.M.H., G.D.M., N.A.K., S.L.C., M.Q., S.S.R., L.W., M.H., P.S., C.K., A.K.K., D.N.F., K.J.C., A.H., M.L.M., C.L.E., A.R., A.L.R., C.L.M., T.W.L., and K.M. contributed to the data and edited/reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lauren E. Appell, Division of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 1 Children’s Way, Slot 512-10A, Little Rock, AR 72202; email: LEAppell@uams.edu.

References

Author notes

The data that support the findings of this report are available on request from the corresponding author, Lauren E. Appell (LEAppell@uams.edu).