Key Points

Dimeric PKM2 is a novel regulator of SNAP23-mediated exocytosis in platelets.

PKM2 deletion or limiting PKM2 dimerzation in platelets reduces platelet releasate–induced NETosis and susceptibility to venous thrombosis.

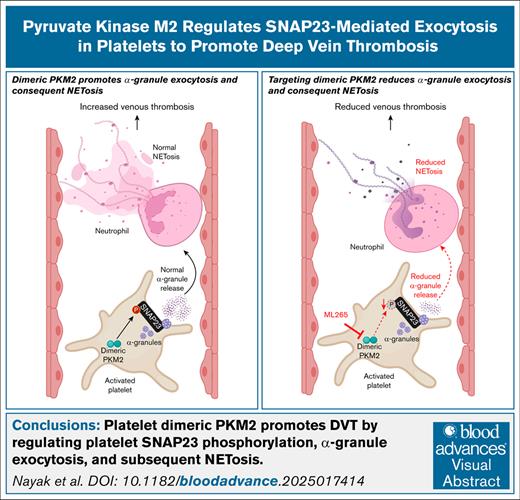

Visual Abstract

Little is known about the role of metabolic regulatory mechanisms in the pathobiology of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Recent studies have demonstrated the involvement of the metabolic enzyme pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in platelet function; however, whether platelet PKM2 contributes to DVT has not yet been investigated. Using platelet-specific PKM2−/− (PKM2Plt-KO) or wild-type (WT) mice orally administered ML265 (a small molecule that limits PKM2 dimers by stabilizing PKM2 tetramers), we found reduced thrombus burden at 48 hours after surgery in the inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis model compared with littermate controls. This reduction was associated with lower levels of citrullinated histone H3, a marker of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET), in the harvested thrombi and improved IVC wall contraction and relaxation responses (assessed by myography). Mechanistically, thrombin-stimulated platelets from PKM2Plt-KO mice or ML265-pretreated platelets from WT mice showed reduced SNAP23 phosphorylation and diminished PF4 release (a marker of α-granule exocytosis). The releasate collected from thrombin-stimulated platelets was less effective at inducing NETosis compared to respective controls. Using ML265-pretreated human whole blood perfused over a tissue factor–coated surface at a venous shear rate, we found that the area covered by platelet-leukocyte aggregates was profoundly reduced compared to vehicle control. Consistent with murine data, human platelets pretreated with ML265 and stimulated with thrombin exhibited decreased PF4 release and generated releasates that were less potent in inducing NETosis. These findings, to our knowledge, reveal for the first time that targeting PKM2 genetically or pharmacologically reduces SNAP23-mediated α-granule exocytosis in platelets, platelet releasate–induced NETosis, and susceptibility to DVT.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is the most prevalent vascular pathology after myocardial infarction and stroke.1 DVT is characterized by high morbidity and mortality: one-third of patients die within 1 month of diagnosis, and another third experience VTE recurrence within 10 years.2 Anticoagulants, the mainstay of treatment for VTE today, have shown efficacy in reducing the risk of recurrence in multiple clinical trials; however, their use is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding. This problem is especially important for individuals with a persistent thrombotic risk factor or unprovoked DVT, who often require an extended duration of treatment with anticoagulants.3,4 Thus, there is an unmet need for new therapies to treat acute DVT and prevent recurrence with less risk of bleeding.

Recent advances in venous thrombosis research have shown that the mechanisms of DVT initiation resemble a local inflammatory response.5 After blood flow restriction, platelets and neutrophils adhere to the activated endothelium to initiate venous thrombus formation. Upon recruitment, platelets undergo activation and release several prothrombotic and proinflammatory mediators from their α-granules, which can promote neutrophil activation and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET), a process known as NETosis. NET are composed of DNA strands decorated with histones and other proteins that serve as a scaffold, facilitating the coagulation cascade and the accrual of additional platelets onto the vein wall, thereby forming a positive feedback loop that propagates DVT. The current understanding of DVT as an inflammation-driven process, rather than merely coagulation-dependent thrombosis, paves the way for identifying new therapeutic targets.

The inflammatory process involves profound reprogramming of cellular metabolism.6 This aligns with metabolic profiling studies of plasma from individuals with DVT and mice subjected to experimental DVT, which have revealed significant alterations in carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid, and energy metabolism compared to healthy controls, reflecting the metabolic shifts that drive disease progression.7-10 These studies suggest that targeting cellular metabolic pathways could offer a novel approach to DVT prevention. One promising target is the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase (PK) isoenzyme M2 (PKM2), which is highly expressed in platelets, neutrophils, and other cells involved in DVT pathogenesis. Unlike other PK isoenzymes (PKR, PKL, and PKM1) that function exclusively as tetramers, PKM2 can function as either a tetramer or a dimer, exhibiting different biological activities. Although the tetramer primarily catalyzes the final step of glycolysis (converting phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate), the dimer can mediate nonglycolytic functions, eliciting multiple cellular effects due to its protein kinase activity.11-14 Previously, we have reported that limiting PKM2 dimerization in platelets reduces susceptibility to arterial thrombosis without altering hemostasis.15 The mechanistic role of platelet PKM2 in regulating DVT has not been investigated.

In this study, using platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice and the small molecule ML265, we tested the hypothesis that dimeric PKM2 regulates venous thrombosis by modulating platelet α-granule release and consequent NETosis. To assess the translational relevance of our findings, we investigated ex vivo thrombus formation under conditions mimicking venous blood flow using human blood pretreated with ML265.

Materials and Methods

Detailed information on materials and methods is provided in the online supplement. supplemental Data.

Mice

Male mice aged 12 to 13 weeks on the C57BL/6J background were used throughout the study. Wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice (PKM2fl/flPF4Cre+) were generated by crossing PKM2fl/fl with PF4Cre+ mice at the University of Iowa animal facility15; littermate PKM2fl/flPF4Cre˗ mice were used as control. For simplicity, from now on PKM2fl/flPF4Cre+ mice will be referred to as PKM2Plt-KO mice and PKM2fl/fl controls as PKM2WT. Mice were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction as previously described.15 Mice were kept in standard animal housing conditions with controlled temperature and humidity, and they had ad libitum access to a standard chow diet and water. The University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments.

DVT model

DVT was induced using inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis.16 Briefly, mice were anesthetized and underwent a midline laparotomy. A spacer (30-gauge, 3-mm–long needle) was positioned on the exposed IVC, and a permanent narrowing ligature (with 5-0 nonabsorbable silk sutures) was tied around the IVC and spacer immediately caudal to the junction of the left renal vein. Next, the spacer was removed to restrict the IVC blood flow by 80% to 90%. All visible side branches were ligated. Mice were then allowed to recover and were euthanized 48 hours after surgery (the time required for complete thrombus formation in this model). Control and experimental mice were operated on in batches on the same day to minimize day-to-day variation. Thrombi were isolated from the vessels, and their length and weight were measured. In some mice, thrombi were further processed for western blotting.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard error or as median with interquartile range and range, as specified. Categorical variables were presented as counts, proportions, and/or percentages. For continuous variables, differences between 2 groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test or Student t test, and differences between ≥3 groups were evaluated using 1- or 2-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc multiple comparisons test. For categorical variables, differences between 2 groups were evaluated using the Fisher exact test. Two-tailed P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.6.0.).

The University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments. Human venous blood was drawn from healthy donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval from the Institutional Review Board, the University of Iowa. All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Platelet-specific PKM2 deficiency decreases susceptibility to acute venous thrombosis, attenuates NETosis, and improves vein wall response in mice

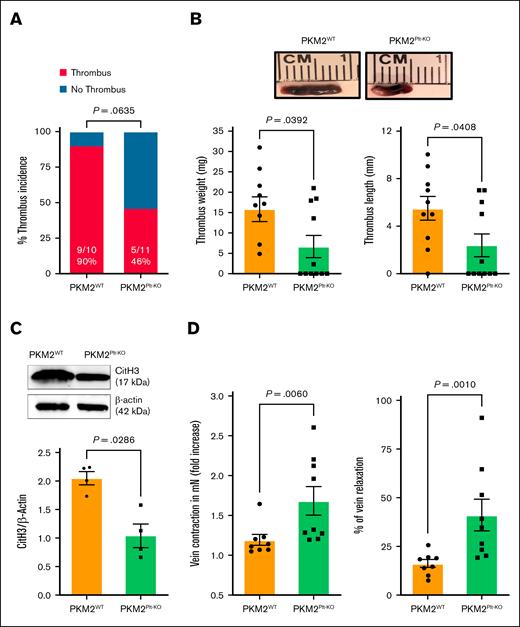

To determine the role of platelet PKM2 in acute DVT, PKM2Plt-KO and littermate control PKM2WT mice were subjected to IVC stenosis. Western blotting confirmed the deletion of PKM2 in platelets but not in neutrophils of PKM2Plt-KO mice (supplemental Figure 1A). On day 2 after surgery, PKM2Plt-KO mice exhibited reduced thrombus burden compared with control, with a clear tendency toward a lower thrombus incidence (P = .064) and a significant reduction in thrombus length and weight (P < .05 vs PKM2WT for both; Figure 1A-B). Recalcification times were comparable between PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice, excluding baseline coagulation differences (supplemental Figure 1B). Because NET contribute to DVT development, we conducted a western blot analysis of thrombus lysates for the NET marker citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3). There was a significant reduction in CitH3 levels in samples from PKM2Plt-KO mice (P < .05 vs PKM2WT; Figure 1C). To evaluate whether the reduced thrombus burden was accompanied by preserved vasomotor function, we quantified contraction and relaxation of the excised IVC in response to phenylephrine and acetylcholine using wire myography. PKM2Plt-KO mice exhibited significantly greater vein wall contraction and relaxation responses (P < .05 vs PKM2WT; Figure 1D), suggesting that the deletion of PKM2 in platelets not only reduces thrombus formation in acute DVT but also supports vessel reactivity.

Platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice were less susceptible to the development of venous thrombosis. (A) Thrombus incidence in PKM2WT (PKM2fl/fl) and PKM2Plt-KO (PKM2fl/flPF4Cre+) mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. (B) Representative IVC thrombi harvested from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis (top); and quantified thrombus weight and thrombus length (n = 10-11 per group; bottom). Values are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); Mann-Whitney U test. (C) CitH3 levels were measured in the thrombus isolated from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice. Representative western blot for CitH3 is shown (upper), and quantitative data are given (lower). β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (D) Fold increase in contraction (left) and percent of relaxation (right) measured by wire myography in IVCs isolated from PKM2WTand PKM2Plt-KO mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. Phenylephrine (0.5 mM) and acetylcholine (1.62 mM) were used for contraction and relaxation, respectively (n = 8-9 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test.

Platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice were less susceptible to the development of venous thrombosis. (A) Thrombus incidence in PKM2WT (PKM2fl/fl) and PKM2Plt-KO (PKM2fl/flPF4Cre+) mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. (B) Representative IVC thrombi harvested from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis (top); and quantified thrombus weight and thrombus length (n = 10-11 per group; bottom). Values are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); Mann-Whitney U test. (C) CitH3 levels were measured in the thrombus isolated from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice. Representative western blot for CitH3 is shown (upper), and quantitative data are given (lower). β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (D) Fold increase in contraction (left) and percent of relaxation (right) measured by wire myography in IVCs isolated from PKM2WTand PKM2Plt-KO mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. Phenylephrine (0.5 mM) and acetylcholine (1.62 mM) were used for contraction and relaxation, respectively (n = 8-9 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test.

Platelet-specific PKM2−/− mice exhibit reduced procoagulant platelets after DVT and NETosis

Recent studies have shown that procoagulant platelets (defined by triple positivity for CD41, phosphatidylserine, and P-selectin) contribute to venous thrombosis.17 Our results revealed a significantly lower level of procoagulant platelets in PKM2Plt-KO mice than in PKM2WT controls 48 hours after DVT surgery (supplemental Figure 2). Next, we used an in vitro NETosis assay to evaluate whether platelet PKM2 affects the ability of platelets to promote NETosis. Platelets from either PKM2Plt-KO or PKM2WT mice were stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin and coincubated with neutrophils isolated from WT mice. At this concentration, thrombin does not activate neutrophils (supplemental Figure 3). The experiments revealed that the percentage of WT neutrophils forming NET was decreased when coincubated with thrombin-stimulated platelets from PKM2Plt-KO mice (P < .05 vs thrombin-stimulated platelets from PKM2WT mice; supplemental Figure 4). To determine whether this effect was the consequence of reduced release of mediators from platelets, in a separate set of experiments, neutrophils isolated from WT mice were treated with releasates from thrombin-stimulated platelets. The experiments revealed that the percentage of WT neutrophils releasing NET was reduced when treated with releasates from thrombin-stimulated platelets of PKM2Plt-KO mice (P < .05 vs releasates of thrombin-stimulated platelets from PKM2WTmice; Figure 2A). These in vitro findings are consistent with the reduced amount of CitH3 in thrombi obtained from PKM2Plt-KO mice (Figure 1C), suggesting that platelet PKM2 may contribute to acute DVT by promoting NETosis.

PKM2 regulates SNAP-23–mediated platelet exocytosis and consequent NETosis. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating bone marrow–derived WT neutrophils with releasates collected from thrombin (0.1 U/mL)-activated platelets isolated from PKM2WT or PKM2Plt-KO mice. Representative microphotographs (left) of NET in lower magnification (20×) and higher magnification (100×) stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA, green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei, blue). Higher magnification images show NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm). Quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET (right) calculated in lower magnification (20×; n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test. (B) Platelets isolated from WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes), and the level of SNAP-23 phosphorylation was measured by western blot; shown are a representative western blot (upper) and a densitometry analysis (lower) of western blots (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (C) Platelets isolated from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test.

PKM2 regulates SNAP-23–mediated platelet exocytosis and consequent NETosis. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating bone marrow–derived WT neutrophils with releasates collected from thrombin (0.1 U/mL)-activated platelets isolated from PKM2WT or PKM2Plt-KO mice. Representative microphotographs (left) of NET in lower magnification (20×) and higher magnification (100×) stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA, green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei, blue). Higher magnification images show NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm). Quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET (right) calculated in lower magnification (20×; n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test. (B) Platelets isolated from WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes), and the level of SNAP-23 phosphorylation was measured by western blot; shown are a representative western blot (upper) and a densitometry analysis (lower) of western blots (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (C) Platelets isolated from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test.

Among the mediators released by activated platelets, PF4, stored in their α-granules, is a known stimulator of NETosis.18 Therefore, we next investigated whether platelet PKM2 regulates α-granule release, focusing on SNAP23, a core component of the SNARE protein complex required for this process.19 Western blot analysis revealed a decrease in SNAP23 phosphorylation in lysates of thrombin-stimulated PKM2Plt-KO platelets, along with an associated decrease in the amount of PF4 released by platelets into the medium (P < .05 vs PKM2Plt-KO platelets; Figure 2B-C). Because no direct loading control can be used for platelet releasates, we normalized the PF4 level in supernatants with Ponceau staining (Figure 2C, bottom panel). Similar results were observed when convulxin was used as an agonist (supplemental Figure 5A-B). To exclude the possibility of reduced PF4 packaging in the α-granules of PKM2Plt-KO mice, we measured PF4 levels in whole platelet lysates. No significant differences in PF4 levels were observed between platelet samples from PKM2WT and PKM2Plt-KO mice (supplemental Figure 5C). Mechanistically, these findings suggest that platelet PKM2 might regulate NETosis by modulating α-granule exocytosis via SNAP23 phosphorylation.

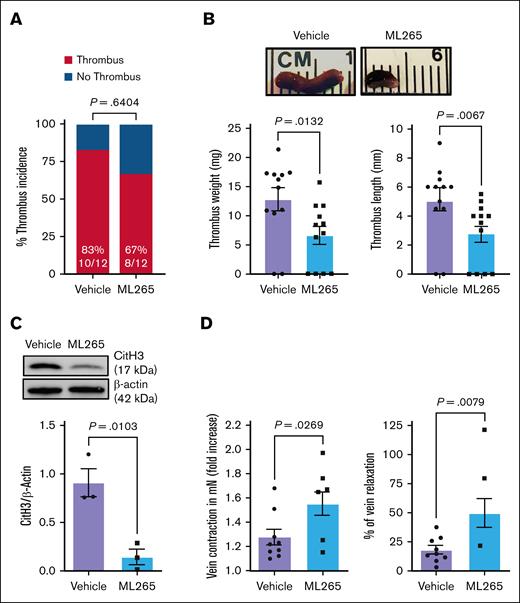

WT mice treated with ML265 exhibit reduced susceptibility to acute venous thrombosis and NETosis and improved vein wall response

To assess the translational potential of targeting PKM2 for DVT protection, we investigated whether ML265 treatment could reduce thrombus burden in WT mice subjected to IVC stenosis. Previously, we have reported that the level of dimeric PKM2 increases after platelet activation and that ML265 counteracts this by stabilizing tetrameric PKM2 both in mouse and human platelets.15 To investigate whether dimeric PKM2 levels also increase in circulating platelets after experimental DVT, we examined mouse platelets 48 hours after surgery and observed a significant increase in dimeric PKM2 compared with sham-operated controls (supplemental Figure 6A). The ML265 dose of 50 mg/kg was chosen based on published studies showing its antithrombotic effect in the FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombosis model.15 On day 2 after surgery, we found that mice orally gavaged with ML265 had similar thrombus incidence (Figure 3A) but a significant decrease in thrombus length and weight (P < .05 vs vehicle-treated WT; Figure 3B). Western blotting of thrombus lysates revealed a significant reduction of CitH3 (marker of NET) in ML265-treated WT mice (P < .05 vs vehicle-treated WT; Figure 3C). Furthermore, ML265-treated mice demonstrated increased vein wall contraction and relaxation responses (P < .05 vs vehicle-treated WT; Figure 3D). These findings suggest that pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization mitigates thrombus formation, attenuates NETosis, and preserves vascular response in acute DVT, mirroring the effects observed in PKM2Plt-KO mice.

Pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization reduces susceptibility to acute venous thrombosis and improves vein wall response in the WT mice. (A) Thrombus incidence in vehicle- or ML265-treated mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. (B) Representative IVC thrombus (top) harvested 48 hours after stenosis from vehicle- or ML265-treated mice (50 mg/kg) is shown, along with quantified thrombus weight and thrombus length (n = 12 per group; bottom). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test. (C) The level of CitH3 was measured in the thrombus isolated from vehicle- and ML265-treated mice. A representative western blot for CitH3 is shown. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (D) Fold increase in contraction (left) and percent of relaxation (right) measured by wire myograph (DMT 610M) in IVCs isolated from vehicle- and ML265 (50 mg/kg)-treated mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. Phenylephrine (0.5 mM) and acetylcholine (1.62 mM) were used for contraction and relaxation, respectively (n = 8-9 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test and Mann-Whitney U test are used for the fold increase in contraction and percent of relaxation, respectively.

Pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization reduces susceptibility to acute venous thrombosis and improves vein wall response in the WT mice. (A) Thrombus incidence in vehicle- or ML265-treated mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. (B) Representative IVC thrombus (top) harvested 48 hours after stenosis from vehicle- or ML265-treated mice (50 mg/kg) is shown, along with quantified thrombus weight and thrombus length (n = 12 per group; bottom). Values are mean ± SEM; Mann-Whitney U test. (C) The level of CitH3 was measured in the thrombus isolated from vehicle- and ML265-treated mice. A representative western blot for CitH3 is shown. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (D) Fold increase in contraction (left) and percent of relaxation (right) measured by wire myograph (DMT 610M) in IVCs isolated from vehicle- and ML265 (50 mg/kg)-treated mice 48 hours after IVC stenosis. Phenylephrine (0.5 mM) and acetylcholine (1.62 mM) were used for contraction and relaxation, respectively (n = 8-9 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test and Mann-Whitney U test are used for the fold increase in contraction and percent of relaxation, respectively.

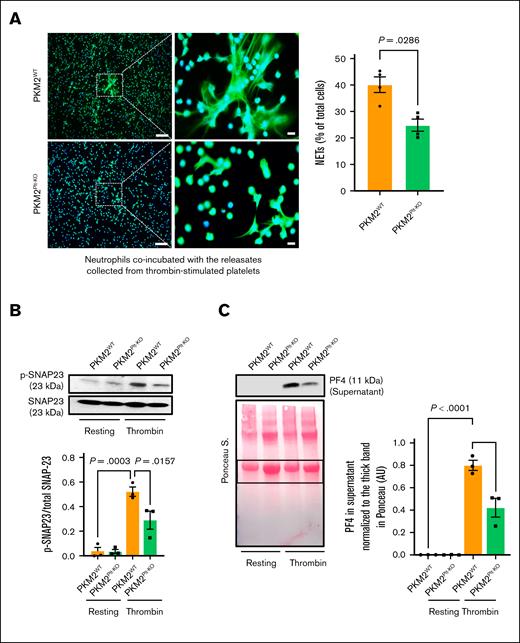

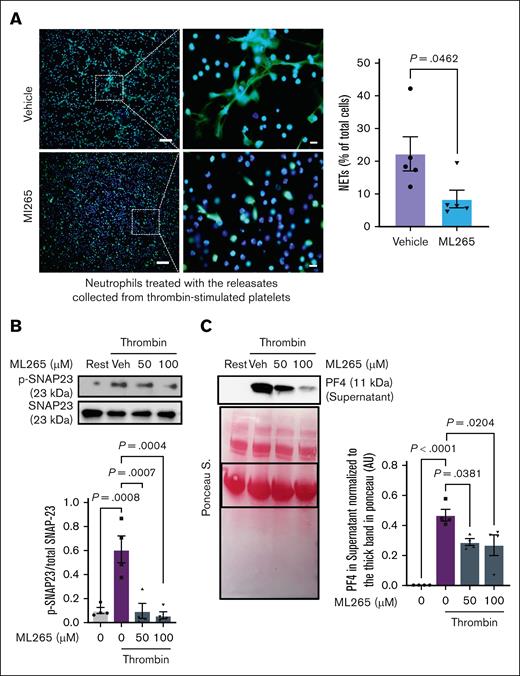

The reduction in NETosis detected in thrombi from ML265-treated mice could result from limited PKM2 dimerization in multiple cell types involved in venous thrombus formation. To elucidate whether limiting PKM2 dimerization in platelets could contribute to this effect, we performed an in vitro NETosis assay. Neutrophils isolated from WT mice were coincubated with thrombin-stimulated WT platelets pretreated with either ML265 or vehicle. In a separate experimental setup, WT neutrophils were treated with platelet releasates from either ML265- or vehicle-treated activated platelets. We observed significantly less NETosis in neutrophils coincubated with ML265-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets (P < .05 vs vehicle-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets; supplemental Figure 6B). Similarly, the percentage of NET-positive cells was decreased when treated with releasates from ML265-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets (P < .05 vs releasates from vehicle-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets; Figure 4A). No significant changes were observed when the neutrophils were coincubated with resting platelets pretreated with either vehicle or ML265 (supplemental Figure 7). Furthermore, as detected by western blotting, pretreatment of WT platelets with ML265 significantly reduced SNAP23 phosphorylation and PF4 release into the medium after stimulation with thrombin (P < .05 vs vehicle-pretreated thrombin-stimulated WT platelets; Figure 4B-C). Ponceau staining of the PF4 western blot showed that loading was comparable among samples (Figure 4C bottom panel). Together, these findings suggest that ML265 may attenuate venous thrombus formation, at least in part, by reducing SNAP23 phosphorylation and α-granule exocytosis in platelets, thereby inhibiting NETosis.

Limiting PKM2 dimerization inhibits NETosis in vitro and reduces SNAP23 phosphorylation and α-granule exocytosis in platelets. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating bone marrow–derived WT neutrophils with the releasates collected from ML265 (100 μM)- or vehicle-pretreated, thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL) platelets. Representative microphotographs of NET in lower magnification (20×) and higher magnification (100×) stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA, green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei, blue) are shown on the left; higher magnification images showing NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm). Quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET in lower magnification is shown on the right (n =5 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (B) WT platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes), and the level of SNAP-23 phosphorylation was measured by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows a densitometry analysis of western blots (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (C) Platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Rest, resting platelets; Veh, vehicle.

Limiting PKM2 dimerization inhibits NETosis in vitro and reduces SNAP23 phosphorylation and α-granule exocytosis in platelets. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating bone marrow–derived WT neutrophils with the releasates collected from ML265 (100 μM)- or vehicle-pretreated, thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL) platelets. Representative microphotographs of NET in lower magnification (20×) and higher magnification (100×) stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA, green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei, blue) are shown on the left; higher magnification images showing NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm). Quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET in lower magnification is shown on the right (n =5 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (B) WT platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes), and the level of SNAP-23 phosphorylation was measured by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows a densitometry analysis of western blots (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (C) Platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 4 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Rest, resting platelets; Veh, vehicle.

Pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization reduces ex vivo thrombus formation at a venous shear rate in human whole blood

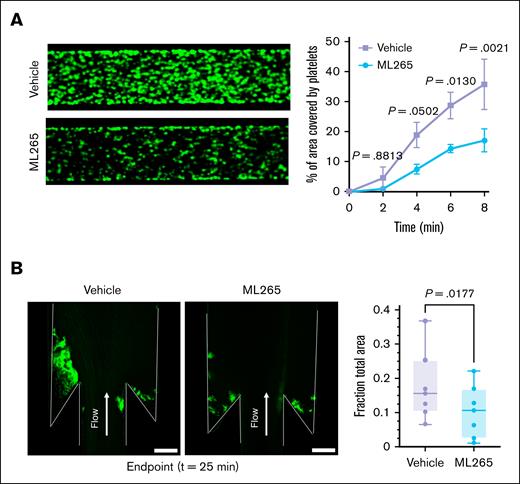

To assess the translational relevance of our findings, we investigated ex vivo thrombus formation in human blood pretreated with ML265 or vehicle under conditions mimicking venous blood flow. In a BioFlux flow system, DiOC6-labeled human whole blood was perfused through tissue factor (TF)–covered microfluidic channels at a shear rate of 500 s˗1. Quantitative analysis revealed that the percentage of area covered by the thrombus (quantified as platelet-leukocyte aggregates) was significantly reduced in ML265-pretreated samples (P < .05 vs vehicle-treated samples; Figure 5A). To bring our experiments closer to the physiology of human veins, we used a custom DVT microfluidic model that mimics the hemodynamic conditions of venous valve pockets, where thrombi frequently form. In this model, thrombus formation is initiated by immobilized TF and supported by the low-shear vortical flows within the valve pocket (supplemental Figure 8). After 25 minutes of perfusing DiOC6-labeled human whole blood through this device, time-lapse video microscopy revealed a significantly reduced accumulation of blood cells in thrombus forming within the valve pocket region in ML265-pretreated samples (P < .05 vs vehicle-pretreated samples; Figure 5B).

Limiting PKM2 dimerization reduces ex vivo thrombus formation in human whole blood at a venous shear rate. (A) Human whole blood pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (150 μM) was perfused over a TF-coated surface for 8 minutes at a shear rate of 500 s–1 in a BioFlux microfluidic flow chamber system; the representative image at 8 minutes (left) and the quantification of thrombus growth (right) on the TF-coated surface over time are shown. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group); 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (B) Human whole blood pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (150 μM) was perfused over a TF-coated surface for 25 minutes in a custom-made DVT device. Accumulation of blood cells after 25 minutes of blood flow. Blood cells were stained with DiOC6 in green. The left panel shows the representative image, and the right panel shows the quantification of thrombus growth (fraction of total area) at 25 minutes (the end point of the assay). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group); paired t test.

Limiting PKM2 dimerization reduces ex vivo thrombus formation in human whole blood at a venous shear rate. (A) Human whole blood pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (150 μM) was perfused over a TF-coated surface for 8 minutes at a shear rate of 500 s–1 in a BioFlux microfluidic flow chamber system; the representative image at 8 minutes (left) and the quantification of thrombus growth (right) on the TF-coated surface over time are shown. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group); 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (B) Human whole blood pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (150 μM) was perfused over a TF-coated surface for 25 minutes in a custom-made DVT device. Accumulation of blood cells after 25 minutes of blood flow. Blood cells were stained with DiOC6 in green. The left panel shows the representative image, and the right panel shows the quantification of thrombus growth (fraction of total area) at 25 minutes (the end point of the assay). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group); paired t test.

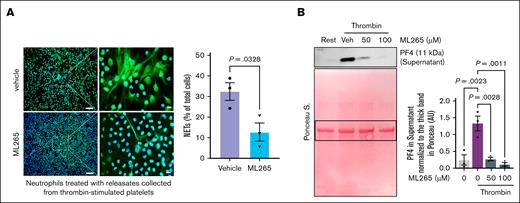

To confirm that the reduced thrombus formation in human blood observed in the microfluidic systems was at least partially caused by inhibition of NETosis secondary to limiting PKM2 dimerization in platelets, we again used the in vitro NETosis assay. In this assay, human neutrophils were coincubated with thrombin-stimulated human platelets that had been pretreated with ML265 or vehicle. In parallel experiments, human neutrophils were coincubated with releasates from thrombin-stimulated human platelets that had been pretreated with ML265 or vehicle. The experiments revealed a significant decrease in the percentage of neutrophils releasing extracellular traps when coincubated with thrombin-stimulated ML265-pretreated platelets (P < .05 vs thrombin-stimulated vehicle-pretreated platelets; supplemental Figure 9). Similarly, we observed significantly less NETosis in neutrophils treated with human platelet releasates from ML265-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets compared to vehicle-pretreated thrombin-stimulated platelets (Figure 6A). Additionally, by using western blotting, we found that pretreatment of platelets with ML265 substantially decreased the level of PF4 released by platelets into the medium after stimulation with thrombin (P < .05 vs thrombin-stimulated vehicle-pretreated platelets; Figure 6B). Ponceau staining of PF4 westen blot showed that loading was comparable among samples (Figure 6B). These findings corroborate our observations in murine models and further support the translational potential of limiting PKM2 dimerization for thromboprophylaxis in humans.

Limiting PKM2 dimerization inhibits NETosis in vitro and reduces α-granule exocytosis in platelets from human blood. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating human neutrophils with releasates collected from thrombin (0.1 U/mL)-activated human platelets in the presence or absence of ML265 (100 μM); representative microphotographs (left) of NET stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA; green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei; blue) are shown in lower (20×) and higher magnification (100×); higher magnification images showing NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm); quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET (n = 3 per group; right). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (B) Human platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated by thrombin (0.1U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Rest, resting platelets; Veh, vehicle.

Limiting PKM2 dimerization inhibits NETosis in vitro and reduces α-granule exocytosis in platelets from human blood. (A) NETosis assay was performed by stimulating human neutrophils with releasates collected from thrombin (0.1 U/mL)-activated human platelets in the presence or absence of ML265 (100 μM); representative microphotographs (left) of NET stained with Sytox green (stains extracellular DNA; green) and counterstained with Hoechst (stains nuclei; blue) are shown in lower (20×) and higher magnification (100×); higher magnification images showing NET from the boxed regions (scale bar for 20× image, 50 μm; scale bar for 100× image, 10 μm); quantification of the percentage of cells releasing NET (n = 3 per group; right). Values are mean ± SEM; unpaired Student t test. (B) Human platelets pretreated with vehicle or ML265 (50 and 100 μM; 10 minutes) were stimulated by thrombin (0.1U/mL; 2 minutes) and centrifuged for 3 minutes; the level of PF4 was measured in the supernatant by western blot. The upper panel shows a representative western blot, and the lower panel shows Ponceau S staining (n = 3 per group). Values are mean ± SEM; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. Rest, resting platelets; Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

The mainstay of current DVT treatment is oral anticoagulant therapy. However, due to the substantial overlap in the mechanisms of pathological thrombosis and normal hemostasis, the use of anticoagulants as prophylactic and therapeutic treatment is associated with an elevated risk of bleeding. This challenge necessitates the search for novel treatment approaches that effectively manage DVT while minimizing this risk. Herein, we demonstrated, to our knowledge, for the first time that genetic deletion of the metabolic enzyme PKM2 in platelets or pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization significantly reduces venous thrombus formation and preserves vein wall response in mice. The novelty of our study lies not only in identifying the role of PKM2 in acute DVT but also in uncovering its mechanistic involvement in platelet exocytosis and subsequent NETosis processes critical to disease pathophysiology. From a translational perspective, we demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization significantly reduces human platelets to induce NETosis and platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation in whole blood within a microfluidic model that mimics the hemodynamic conditions of venous valve pockets, where thrombi frequently form. Our findings reveal a previously unidentified role of platelet PKM2 in regulating exocytosis, NETosis, and DVT pathogenesis.

We demonstrated that genetic deletion of PKM2 in platelets not only reduces susceptibility to venous thrombosis but also preserves the IVC wall contraction and relaxation responses. A previous study reported that impairment in venous relaxation in the IVC stenosis model was attributed to prolonged stretching of the venous wall by the thrombus and the associated endothelial damage.20 This suggests that the preserved vein wall contraction and relaxation observed in PKM2Plt-KO mice could result from reduced mechanical stress exerted by smaller thrombi onto the venous wall. Although no significant difference in IVC contraction between WT and interleukin-6–deficient mice was observed by Metz et al,20 it is plausible that reduced exposure of the venous wall to other proinflammatory mediators capable of inducing vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cell dysfunction could contribute to enhanced contractile and relaxation responses in PKM2Plt-KO mice.21-23 Based on these results, we speculate that targeting PKM2 may improve long-term DVT outcomes and reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome.

Previously, we have demonstrated that PKM2 contributes to platelet function and experimental arterial thrombosis.15 Notably, no significant impact of platelet-specific PKM2 deletion on hemostasis was observed,15 making this enzyme an attractive antithrombotic target beyond the coagulation cascade. Given the physiological and molecular differences between arterial and venous thrombosis, we investigated the role of platelet PKM2 in DVT pathobiology. Evidence from animal studies suggests that platelets promote DVT by releasing several proinflammatory mediators that induce NETosis, a process critical to venous thrombus formation. Herein, to our knowledge, we identified for the first time platelet PKM2 as a novel regulator of NETosis, evidenced by the reduced CitH3 levels in western blots of thrombus lysates from platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice. We further corroborated this regulatory role of platelet PKM2 using the in vitro NETosis assay, which demonstrated a reduced percentage of extracellular traps–releasing WT neutrophils in the presence of releasates from thrombin-stimulated PKM2-deficient platelets. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that reduced NETosis in mice was associated with reduced susceptibility to venous thrombosis in the IVC stenosis model.24 To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of platelet-specific PKM2 deletion, we focused on the release of proinflammatory mediators stored in platelet α-granules, because this is one of the key processes by which platelets promote neutrophil activation and NETosis.18 Our in vitro experiments revealed that PKM2-deficient platelets exhibited reduced PF4 secretion when stimulated by thrombin, indicating reduced α-granule release. Notably, this effect was accompanied by reduced SNAP23 phosphorylation, a prerequisite for assembling the SNARE complex that governs membrane fusion between secretory granules and the plasma membrane.25 These observations are consistent with prior studies in A549 and promyelocytic HL-60 cancer cells demonstrating that dimeric PKM2 directly phosphorylates SNAP-23 and that PKM2 knockdown by small interfering RNA reduces SNAP23 phosphorylation.26,27 Together, these studies highlight the importance of this nonglycolytic PKM2 function in platelet exocytosis and venous thrombosis.

Recent studies have highlighted the role of procoagulant platelets in the pathogenesis of venous thrombosis.17 Consistent with this, we found a significant reduction in circulating procoagulant platelet levels 48 hours after DVT surgery in platelet-specific PKM2-deficient mice, suggesting platelet PKM2 supports the formation of this prothrombotic platelet phenotype. Additionally, we found that circulating platelets exhibited a significant increase in dimeric PKM2 at 48 hours after DVT induction compared with sham-operated controls. These observations suggest that dimeric PKM2 may also contribute to the pathophysiology of venous thrombosis by promoting the procoagulant platelet phenotype in addition to NETosis.

It needs to be acknowledged that PKM2 functions in platelets extend beyond SNAP23 phosphorylation. In resting platelets, PKM2 predominantly exists as a tetramer with high PK activity, efficiently converting phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate and thereby maintaining ATP levels. Upon platelet activation, PKM2 transitions to a dimeric form with reduced PK activity, resulting in the accumulation of upstream glycolytic intermediates and regulatory molecules that enhance glucose uptake and oxidation through “upper” glycolysis. This metabolic shift enables a rapid increase in ATP production to meet the heightened energy demands of activated platelets. Moreover, the dimeric form of PKM2, but not the tetrameric form of PKM2, possesses protein kinase activity, leading to phosphorylation of key signaling molecules, including SNAP23. As demonstrated in nucleated cells, another potential target of dimeric PKM2 is signal transducer and activator of transcription 3,11 which mediates platelet responses to collagen and thrombin.28 Consequently, limiting PKM2 dimerization may interfere with multiple signaling pathways essential for platelet activation. Because both genetic ablation of PKM2 (removing all forms) and pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 dimerization (specifically reducing the dimeric form) similarly reduce SNAP23 phosphorylation and α-granule exocytosis, it is tempting to speculate that the principal mechanism underlying the observed inhibition of platelet function is the loss of dimeric PKM2 protein kinase activity rather than an alteration in its glycolytic role fulfilled primarily by tetrameric PKM2.

To assess the translational potential of targeting PKM2 for protection against acute DVT, we investigated the effects of ML265, a small molecule that limits PKM2 dimerization by stabilizing tetramers.29 Previously, we have demonstated that ML265 limits the formation of dimeric PKM2 both in mouse and human platelets, thereby reducing its glycolytic and nonglycolytic functions.15 Our findings in WT mice systemically administered ML265 mirrors the results observed in PKM2Plt-KO mice subjected to IVC stenosis. ML265-treated mice significantly reduced thrombus length and weight, reduced NETosis in the harvested thrombi, and preserved IVC contraction and relaxation responses. Although systemic administration of ML265 implies that PKM2 dimerization was inhibited in multiple cell types involved in venous thrombosis, the similarities between the results obtained in the in vitro NETosis assay with ML265-pretreated and PKM2-deficient platelets or their releasates suggest that the systemic effect of ML265 was, at least in part, mediated by the mediators released from activated platelets. These results validate our observations from the genetic knockout model and support the pharmacological targeting of PKM2 as a promising therapeutic approach for DVT prevention.

To enhance the translational relevance of our findings, we investigated the effect of ML265 on ex vivo thrombus formation in human blood using 2 complementary microfluidic models mimicking venous flow conditions. The BioFlux system allowed us to quantify thrombus formation under well-controlled, constant blood flow, whereas the custom DVT microfluidic device, which uniquely recapitulates the hemodynamics of venous valve pockets, provided an even more physiologically relevant setting. In both models, thrombus formation was stimulated by immobilized TF, the primary trigger of the coagulation cascade in vivo, whose expression in endothelial cells is upregulated under conditions of reduced venous blood flow.30,31 Our experiments showed that pretreatment with ML265 significantly reduced thrombus formation in human whole blood in both models. Furthermore, similar to studies with mouse platelets, thrombin-stimulated ML265-pretreated human platelets demonstrated a reduced capacity to induce NETosis in human neutrophils and decreased α-granule exocytosis, as evidenced by reduced PF4 release. The consistency of these findings across biological species suggests the robustness of inhibiting venous thrombosis upon limiting PKM2 dimerization and underscores its translational potential.

A key strength of our study lies in demonstrating the translational potential of targeting PKM2 by ML265 for thromboprophylaxis. The pharmacokinetic profile of ML265 is characterized by good oral bioavailability, low clearance, and a long half-life (5.8 hours) in mice.29 At a dose of 50 mg/kg administered twice daily for 5 days, ML265 was well tolerated, as evidenced by no changes in mouse body weight and the absence of side effects (based on complete blood count, serum biochemistry tests, and histological analysis of several tissues) in toxicity studies.29 Another strength of this study is that it addresses a gap in the literature by focusing on metabolic pathways involved in the pathobiology of DVT. By modulating the metabolic enzyme PKM2 that contributes to thrombosis and inflammation, it may be possible to limit DVT progression while reducing reliance on anticoagulants that are associated with bleeding complications. Despite these strengths, a limitation of the study is that although DVT affects both sexes in humans, female mice were not included in this study. This decision was based on existing evidence that female mice are less susceptible to acute DVT due to sex-specific differences in growth hormone levels and the preservation of uterine venous flow to the IVC, which may limit thrombus progression and confound results.32

In conclusion, we demonstrated that platelet PKM2 plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of acute DVT by regulating platelet SNAP23 phosphorylation, α-granule exocytosis, and subsequent NETosis. Given that the current drugs used for treating venous thrombosis carry a high risk of bleeding, these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting PKM2 dimerization for DVT prevention while preserving hemostasis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Makoto Itakura for sharing the SNAP23 antibodies.

The study is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R35HL139926 and R01HL174460). M.K.N. is supported by the American Heart Association career development award (942168). The laboratory of K.B.N. is supported by grants from National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, United States (R01HL151984 and R33HL141794) and the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, United States (H30MC24049, Hemophilia Treatment Centers).

Authorship

Contribution: M.K.N. and A.K.C. contributed to conceptualization, designing experiments, and analyzing results; S.R.L. provided intellectual input; M.K.N., I.B., and A.K.C. contributed to writing and editing the manuscript; M.K.N., G.D.F., T.B., M.G., R.B.P., M.K., A.J., N.C., M.J., J.K., S.K., and K.B.N. performed the experiments; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Manasa K. Nayak, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, 3120 Medical Labs, Iowa City, IA, 52242; email: manasa-nayak@uiowa.edu; and Anil K. Chauhan, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, 3120 Medical Labs, Iowa City, IA, 52242; email: anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu.

References

Author notes

Data supporting the findings of the study are available from the corresponding authors, Manasa K. Nayak (manasa-nayak@uiowa.edu) and Anil K. Chauhan (anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu), on request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.