Key Points

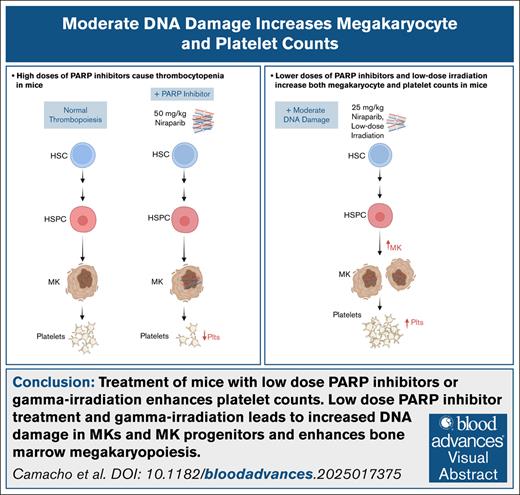

Treatment of mice with low-dose PARP inhibitors or gamma irradiation enhances platelet counts.

Low-dose PARP inhibitor treatment and gamma irradiation increases DNA damage in MKs and MkPs and enhances megakaryopoiesis.

Visual Abstract

Megakaryocytes (MKs) are large, hematopoietic cells with a polyploid, multilobulated nucleus. Although DNA replication in MKs (endomitosis) is well studied, limited investigations have examined the impact of DNA instability on megakaryopoiesis. Poly–adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors are chemotherapeutics that result in accumulation of DNA damage and are commonly associated with thrombocytopenia, presumably mediated through platelet progenitors, MKs. To explore PARP inhibitor–induced thrombocytopenia, we treated mice with the PARP inhibitor niraparib. Although high-dose niraparib treatment led to thrombocytopenia, consistent with clinical observations, lower-dose treatment led to a significant increase in bone marrow MKs, MK progenitors (MkPs), and circulating platelets. This increase was accompanied by elevated DNA damage in both MKs and MkPs, as measured by γH2AX accumulation and comet assays. Notably, platelets from niraparib-treated mice were functionally normal in their response to ADP, thrombin receptor activating peptide, and collagen. Treatment of mice with low-dose gamma irradiation similarly led to DNA damage in MKs and resulted in increased MK and platelet counts, suggesting that moderate DNA damage is a conserved mechanism that enhances megakaryopoiesis and platelet counts. These data reveal a previously unknown relationship between MKs and DNA damage and present a novel target for triggering enhanced platelet production in vivo.

Introduction

DNA is susceptible to damage from normal metabolic processes and external DNA-damaging agents. The cellular DNA damage response (DDR) relies on a complex interplay between pathways that ultimately modulate cell survival or cell death.1 Although generally associated with deleterious responses, accumulation of DNA damage also creates vulnerabilities that are clinically exploited.2,3 Therapeutically targeting the DDR is particularly common in the treatment of tumors.4 Inhibitors of poly–adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP), a sensor of DNA damage central to the DDR, were first released in 2014.2 In physiological conditions, PARP binds to sites of DNA damage and recruits DNA repair effectors that repair DNA lesions. PARP inhibitors (PARPis) such as olaparib and niraparib “trap” PARP at lesions, leading to DNA replication fork stalling and accumulation of DNA damage through the formation of toxic double-stranded breaks.2,5 Notably, PARPis can cause thrombocytopenia in patients,2,5 presumably due to effects of PARP inhibition in platelet-producing cells, megakaryocytes (MKs), because platelets lack DNA.

MKs are large, hematopoietic cells that primarily reside in the bone marrow.6,7 One of the unique and defining features of MKs is their large polyploid nucleus contained within a single nuclear membrane. Currently, the impact of having this sheer volume of DNA (up to 128N) on MK physiology lacks resolution. One of the most critical functions of MKs is to package and release platelets, circulating cells that are essential for maintaining hemostasis and vascular integrity. In several pathologies, the disruption of platelet production (thrombopoiesis) leads to reduced circulating platelet numbers, which significantly increases bleeding risks. Thrombocytopenia occurs when platelet counts drop to dangerously low levels (<150 × 109/L), which can be life threatening due to a heightened risk of bleeding. Thrombocytopenia occurs in multiple conditions, including immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), chemotherapy, surgery, aplastic anemia, HIV infection, and during pregnancy and delivery, among others. Unfortunately, effective, durable treatment for ITP with steroids is not achieved in many patients.8

The lack of efficient therapeutic interventions for thrombocytopenia underscores our poor understanding of the molecular processes that drive MK differentiation and platelet production in both health and stress conditions. In this study, we found that induction of DNA damage with low levels of PARPis and low-dose irradiation led to increased platelet counts. This increase in platelets was accompanied by elevated MK numbers and increased DNA damage in MKs and MK progenitors (MkPs). These results suggest that the DDR is a regulator of megakaryopoiesis and a novel trigger of platelet production, revealing a unique avenue of exploration in MK biology.

Methods

Reagents

Niraparib (MK-4827; Selleckchem) was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide to a stock concentration of 50 mg/mL. For in vivo experimentation, the stock concentration was diluted with 10% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (332607; MilliporeSigma) in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to reach a final concentration of either 50 mg/kg body weight or 25 mg/kg body weight.

Mice

C57BL/6J mice (027C57BL/6) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Worcester, MA).

Flow cytometric analysis of murine platelets in whole blood

After terminal exsanguination into EDTA-coated tubes, whole blood (5 μL) was diluted in 500 μL of Tyrode buffer (catalog no. J67607; Alfa Aesar) and stained with thiazole orange (TO; 200 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Flow cytometric analysis (Accuri C6 plus; BD Biosciences) was performed to identify the frequency of TO+ platelets. To measure platelet activation, 50 μL of murine whole blood was washed in Tyrode buffer, and indicated doses of ADP, U46619, thrombin, and crosslinked collagen-related peptide were incubated with platelets for 15 minutes. P-selectin exposure (WUG 1.9-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]; Emfret Analytics) and activation of αIIbβ3 integrins (JON/A-PE; Emfret Analytics) were determined by flow cytometry. Cell surface glycoprotein (GP) expression on the surface of unactivated platelets was measured in whole blood (CD41 [catalog no. 133904; BioLegend], GPIbα [catalog no. M040-1; Emfret Analytics], and GPVI [catalog no. M011-1; Emfret Analytics]).

Ex vivo MK culture and niraparib treatment

MKs were differentiated from murine bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), as previously published.9,10 Briefly, HSPCs were enriched using a rat anti-mouse lineage panel (catalog no. 133307; BioLegend), followed by magnetic bead isolation using Dynabeads (catalog no. 11415D; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cultured with thrombopoietin (50 ng/mL) for 5 days. On day 1, dimethyl sulfoxide or niraparib was added at indicated doses to HSPC cultures. Differentiated MKs were quantified and defined by gating on live, CD45+Lin–CD41+CD42d+ cells.

Proplatelet production from MKs was manually quantified after 24 hours of niraparib treatment based on images generated from a Nikon TE-2000-E Microscope (Nikon) equipped with a 20× (0.3 numerical aperture [NA]) Plan-Fluor objective, using a Hamamatsu charged-coupled device camera, as previously described.11,12 Briefly, for each replicate, at least 250 cells per condition were counted and scored as either “round” or “proplatelet producing.”

HSPC and MK quantification by flow cytometry

Bone marrow was isolated from 1 tibia and 1 femur per mouse. Single-cell suspensions were analyzed using a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer 4-laser system (16-V-14B-10YG-8R). HSPCs were identified by gating on a live, CD45+Lin– cell suspension, as previously described.9,10 Populations were defined as follows: multipotent progenitors (multipotent progenitor populations 2 [MPP2; CD45+Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+Flt3–CD48+CD150+], MPP3 [CD45+Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+Flt3–CD48+CD150–], and MPP4 [CD45+Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+Flt3+]), MkPs (CD45+Lin–Sca-1-cKit+CD150+CD41+), MKs (CD45+Lin–CD41+CD42d+), short-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs; CD45+ Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+Flt3– CD150–CD48–), HSCs (CD45+Lin–Sca-1+cKit+Flt3– CD150+CD48–), and CD41+ HSCs (CD45+Lin–Sca-1+cKit+Flt3– CD150+CD48–CD41+).

MK ploidy analysis

Bone marrow was isolated from 1 tibia of either niraparib- or vehicle-treated mice by centrifugation at 2500g for 40 seconds. Lysis of red blood cells was performed using ACK buffer (A104921; Gibco) after filtration using a 100-μm cell strainer. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS, fixed, and permeabilized with 70% ethanol. Cells were then stained with a FITC-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody (catalog no. 133904; BioLegend) and propidium iodide (catalog no. P1304-MP; MilliporeSigma) in the presence of ribonuclease A (catalog no. EN0531; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ploidy of CD41+ cells was quantified using flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 Plus).

Intracellular γH2AX staining

Cells were fixed and processed using the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stained with anti- γH2AX (catalog no. 600205; BioLegend). Populations were defined as in the HSPC panel; MPP3 and MPP4 subsets were combined (MPP3-4; CD45+Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD48+CD150–).

Murine models

In vivo administration of PARPis

For the 11-day treatment, C57BL/6J mice were injected intraperitoneally with either niraparib (25 or 50 mg/kg) or vehicle control for 5 consecutive days, followed by 2 days off, and then 4 consecutive days of injections. For the 3-day treatment, mice were injected intraperitoneally for 3 consecutive days. Similarly, olaparib 50 mg/kg or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally in C57BL/6J mice for 5 consecutive days, followed by 3 days off, followed by 5 consecutive days of injections. For nonterminal platelet counts, tail vein venipunctures were performed on specified days. For the long-term monitoring experiment, tail vein punctures continued at indicated days after 11-day treatment cessation. Platelet count, immature platelet fraction, and mean platelet volume (MPV) were quantified using a Sysmex hematology analyzer.

Murine model of gamma irradiation

C57BL/6J mice were irradiated with 0, 50, 100, 150, or 200 cGy (Gammacell 40 extractor). Platelet counts were measured in whole blood before and after irradiation by tail vein venipuncture using a Sysmex hematology analyzer. Bone marrow was isolated as described under “HSPC and MK quantification by flow cytometry.”

Induction of thrombocytopenia

C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected for 5 days with either niraparib (25 mg/kg) or vehicle control (day –5 through day –1). On day 0, an anti-GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g; catalog no. R300; Emfret Analytics) was administered to induce thrombocytopenia. Blood was drawn by tail vein venipuncture or venipuncture from the retro-orbital plexus and platelets counts were measured using a Sysmex hematology analyzer before and after induction of thrombocytopenia until recovery.

Femur processing and immunofluorescence

Femurs were isolated from mice treated with niraparib 25 mg/kg or vehicle and fixed using 4% (weight-to-volume ratio) paraformaldehyde (MilliporeSigma) in PBS for 24 hours, followed by a daily increasing sucrose gradient (10%-30%). Femurs were then frozen using a layer of chilled ethanol and stored at –80°C after embedding in super cryembedding medium (catalog no. R031006; SECTION-LAB Co, Yokohama, Japan) or optimal cutting temperature compound (catalog no. 23-730-571; Fisher Scientific). Sectioning at ∼12-μm thickness was performed on each femur using a tape transfer system13 at a cryostat (CM3050 S; Leica Biosystems), followed by mounting onto microscopy slides (Fisher Scientific). Cryosections were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS, followed by primary antibody labeling overnight at 4°C for CD41 (catalog no. 133902; BioLegend) and/or γH2AX (phospho-histone H2A.X, Ser139, 20E3; Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary staining was done with AlexaFluor 488 and 647–conjugated antibodies raised against the primary rat or rabbit antibody (Invitrogen), and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used for nuclear staining. Labeled cryosections were imaged using a Lionheart FX microscope with a 4× Olympus Plan Fluorite phase objective (NA, 0.13; excitation, 469/35 nm; emission, 525/39 nm) or a Nikon AXR confocal microscope using a 20× objective. MK quantification was performed using an automated imaging platform (Lionheart, Biotek) by selecting CD41+ objects >15 μm with a nucleus. For γH2AX quantification, γH2AX foci were counted manually, with each discrete focus on a confocal plane regarded as a distinct focus.

For extended methodology, see the supplemental Materials.

All procedures were approved by the international animal care and use committee at Boston Children’s Hospital (protocol 00001248).

Results

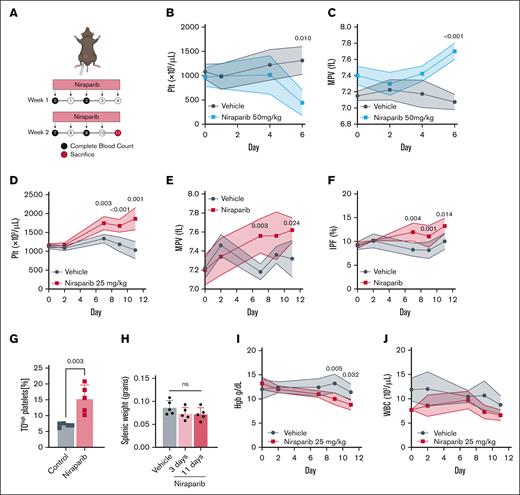

Low-dose PARPi treatment significantly elevates platelet counts in mice

A common side effect of PARPi treatment in patients is thrombocytopenia.2,5 Little is known about the molecular mechanisms of this adverse effect and the influence of genetic instability in MK biology. We first aimed to phenocopy PARPi-induced thrombocytopenia by treating mice with niraparib (Figure 1A). Mice treated with 50 mg/kg niraparib exhibited severe weight loss, markedly reduced platelet counts (Figure 1B), and increased MPV (Figure 1C) after 6 days, hallmarks of severe thrombocytopenia, which led to premature humane experimental termination. Unexpectedly, however, treating mice with lower-dose niraparib (25 mg/kg) led to a significant increase in platelet counts beginning 7 days after treatment and persisting through experimental end point (day 11; Figure 1D). These results suggest that there is a threshold at which niraparib displays opposing effects on platelet production, consistent with rat studies.14,15 To substantiate this thrombocytosis at 25 mg/kg niraparib, we measured MPV (Figure 1E) and immature platelet fraction (Figure 1F); both were elevated, suggestive of new platelet production. Additionally, TO staining of platelets on day 11 revealed that mice treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib had a higher proportion of reticulated platelets (Figure 1G), indicative of platelets of younger age in circulation.16 Upon euthanasia, spleen weights were similar, suggesting no difference in platelet mobilization to or from the spleen (Figure 1H). Quantification of peripheral blood cell counts revealed that mice treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib for 11 days had a concurrent decrease in hemoglobin but no significant change in white blood cell count (Figure 1I-J). Notably, a similar increase in platelet count was observed when mice were treated with the structurally unrelated PARPi compound olaparib, indicating that this effect was not niraparib specific (supplemental Figure 1A-B).

Low-dose niraparib treatment increases platelet production in mice. (A) Schematic outlining niraparib administration: mice were injected intraperitoneally with niraparib or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) at the indicated times. Blood was drawn via tail vein venipuncture and complete blood counts were measured using a Sysmex hematology analyzer. (B) Platelet counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (50 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (C) MPV in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (50 mg/kg; n = 4-5 mice per group). (D) Platelet counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (E) MPV in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (F) IPF in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data in panels B-E are shown as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey correction was used for multiple comparisons. (G) Frequency of reticulated, TOhigh (thiazole orange) platelets in whole blood of vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (H) Spleen weights from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg) after 3 or 11 days of treatment, as indicated (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. (I) Hgb in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg). (J) WBC counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data in I-J are mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. fL, femtoliter; Hgb, hemoglobin; IPF, immature platelet fraction; Plt, platelet; WBC, white blood cell.

Low-dose niraparib treatment increases platelet production in mice. (A) Schematic outlining niraparib administration: mice were injected intraperitoneally with niraparib or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) at the indicated times. Blood was drawn via tail vein venipuncture and complete blood counts were measured using a Sysmex hematology analyzer. (B) Platelet counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (50 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (C) MPV in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (50 mg/kg; n = 4-5 mice per group). (D) Platelet counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (E) MPV in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). (F) IPF in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data in panels B-E are shown as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey correction was used for multiple comparisons. (G) Frequency of reticulated, TOhigh (thiazole orange) platelets in whole blood of vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (H) Spleen weights from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg) after 3 or 11 days of treatment, as indicated (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. (I) Hgb in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg). (J) WBC counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg; n = 5 mice per group). Data in I-J are mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. fL, femtoliter; Hgb, hemoglobin; IPF, immature platelet fraction; Plt, platelet; WBC, white blood cell.

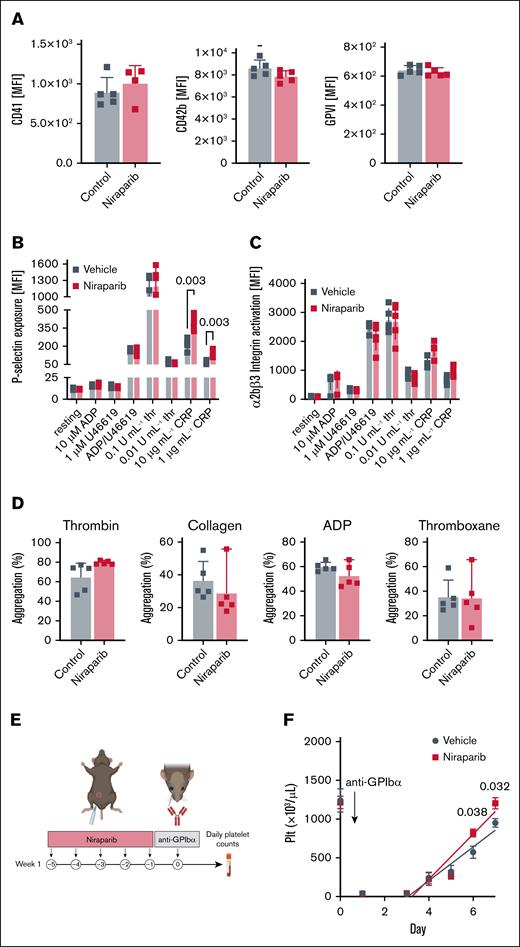

We next tested platelet functionality in 25 mg/kg niraparib– and vehicle-treated mice. Baseline expression of αIIb integrins (CD41), GPIbα, and GPVI were unaltered (Figure 2A), as was platelet activation when whole blood was stimulated with ADP and thrombin (Figure 2B-C). We did, however, observe heightened sensitivity to GPVI stimulation in platelets from niraparib-treated mice treated with collagen-related peptide. This may be due to the increase in reticulated platelets (Figure 1G), which have been reported17,18 to display increased GPVI reactivity (Figure 2B-C). However, platelets from niraparib-treated mice had unaltered aggregation, suggesting that 25 mg/kg niraparib treatment does not elevate thrombotic risk (Figure 2D).

Niraparib-treated mice with increased platelet production retain normal platelet function. Blood was drawn from vehicle- and niraparib-treated (25 mg/kg) mice and (A) Flow cytometry was used to measure mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of αIIb integrins (CD41), GPIbα, and GPVI in resting platelets (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (B-C) Platelets were activated with indicated agonists and surface P-selectin (B) and activated αIIbβ3 integrins (C) were measured by flow cytometry. n = 5 mice per group. Data are mean ± SD; multiple t tests were used. (D) Platelet aggregation was measured using washed platelets isolated from vehicle- and niraparib-treated mice that were treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL), collagen (CRP, 1 μg/mL), ADP (10 μM), or thromboxane (1 μM). Absorbance at 450 nm was used to calculate total aggregation for each sample normalized to the positive and negative controls (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. (E) Schematic of niraparib treatment and in vivo platelet depletion using an anti-GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g per mouse). (F) Platelet counts were measured after anti-GPIbα administration were measured over 6 consecutive days (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. CRP, collagen related peptide; Plt, platelet.

Niraparib-treated mice with increased platelet production retain normal platelet function. Blood was drawn from vehicle- and niraparib-treated (25 mg/kg) mice and (A) Flow cytometry was used to measure mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of αIIb integrins (CD41), GPIbα, and GPVI in resting platelets (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (B-C) Platelets were activated with indicated agonists and surface P-selectin (B) and activated αIIbβ3 integrins (C) were measured by flow cytometry. n = 5 mice per group. Data are mean ± SD; multiple t tests were used. (D) Platelet aggregation was measured using washed platelets isolated from vehicle- and niraparib-treated mice that were treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL), collagen (CRP, 1 μg/mL), ADP (10 μM), or thromboxane (1 μM). Absorbance at 450 nm was used to calculate total aggregation for each sample normalized to the positive and negative controls (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. (E) Schematic of niraparib treatment and in vivo platelet depletion using an anti-GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g per mouse). (F) Platelet counts were measured after anti-GPIbα administration were measured over 6 consecutive days (n = 5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. CRP, collagen related peptide; Plt, platelet.

Finally, to evaluate the impact of 25 mg/kg niraparib on platelet recovery after induction of thrombocytopenia, we preconditioned mice with niraparib, followed by platelet depletion using an anti-GPIbα antibody (Figure 2E). Mice preconditioned with niraparib showed faster recovery and higher platelet counts (Figure 2F) after thrombocytopenia induction. Together, these findings demonstrate that treatment with 25 mg/kg niraparib enhanced the production of functional platelets in mice.

Niraparib treatment increases megakaryopoiesis in mice

To probe the etiology of niraparib-induced platelet production, we assessed the effect of niraparib on HSPC populations (flow cytometry gating strategy outlined in supplemental Figure 2). We observed a significant increase in both MPP2 and MPP3 after 3 days of treatment (Figure 3A). After 11 days of treatment, there was a significant increase in HSCs, MkPs, and MKs, in addition to all MPPs, whereas the number of CD41+ HSCs was unaltered (Figure 3A). These data suggest that niraparib treatment primes HSC differentiation toward the MK lineage. This increase in MK number was validated by immunofluorescent visualization of MKs in femoral cryosections (Figure 3B), revealing an increase in both the number (Figure 3C) and size (Figure 3D) of MKs in niraparib-treated mice. To further substantiate these findings, we examined MKs via 2-photon intravital microscopy in the calvaria of MK/platelet reporter mice (von Willebrand factor–green fluorescent protein).19 In vivo MK quantification and phenotyping also revealed a significant increase in MK number upon niraparib treatment, corroborating our findings from the in situ analysis and confirming that MKs in both groups were alive, not apoptotic, and making proplatelets (Figure 3E-F; supplemental Movies 1-2). To further investigate MK morphology, we performed electron microscopy on femoral whole bone marrow sections from both vehicle- and niraparib-treated mice (supplemental Figure 3). Electron microscopy images revealed no gross changes or abnormalities in MK structure, bone marrow cellularity, or the endothelial cells lining vascular lumens (representative images shown in supplemental Figure 3).

Low-dose niraparib treatment enhances megakaryopoiesis. (A) HSPC counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. Gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2. (B) Representative images of femoral cryosections from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (CD41, green). Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (blue; scale bars, 1000 μm; inset scale bars, 200 μm). (C-D) MK counts (C) and area (D) in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice were quantified in femoral cryosections (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (E) MK/platelet reporter mice (VWF–green fluorescent protein [GFP]) were treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib or vehicle for 7 days, and 2-photon intravital microscopy of the calvaria was performed. Representative images show MKs (cyan) and vasculature (magenta; labeled using Evans Blue; scale bars, 20 μm). (F) Live MKs were quantified by size and GFP signal (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Low-dose niraparib treatment enhances megakaryopoiesis. (A) HSPC counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. Gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2. (B) Representative images of femoral cryosections from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (CD41, green). Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (blue; scale bars, 1000 μm; inset scale bars, 200 μm). (C-D) MK counts (C) and area (D) in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice were quantified in femoral cryosections (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (E) MK/platelet reporter mice (VWF–green fluorescent protein [GFP]) were treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib or vehicle for 7 days, and 2-photon intravital microscopy of the calvaria was performed. Representative images show MKs (cyan) and vasculature (magenta; labeled using Evans Blue; scale bars, 20 μm). (F) Live MKs were quantified by size and GFP signal (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

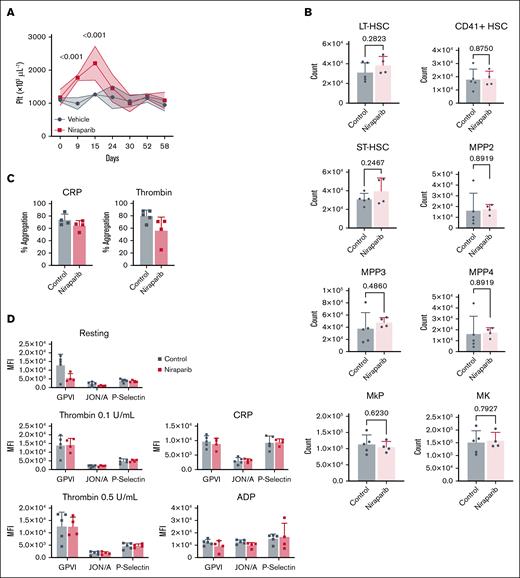

We next wanted to test how long 1 course of niraparib treatment sustained elevated platelet counts and whether HSPC numbers in the bone marrow returned to normal. Therefore, we treated mice with 25 mg/kg niraparib as in Figure 1A. Notably, 1 course of niraparib treatment significantly increased platelet counts for over 2 weeks (Figure 4A). In addition, after ∼6 weeks, there were no significant differences in HSPC counts (Figure 4B), platelet aggregation (Figure 4C), or platelet activation (Figure 4D), suggesting that both bone marrow cells (HSPCs) and platelets recovered from short-term niraparib treatment.

Bone marrow HSPC counts and platelets recover after short-term niraparib treatment. (A) Time course of platelet counts in vehicle- and niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg). Mice were followed and platelet counts measured for 47 days after treatment cessation (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. (B) Absolute counts of HSPC populations 47 days after cessation of niraparib or vehicle treatment were quantified by flow cytometry using the panel outlined in supplemental Figure 2 (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (C) Platelet aggregation after stimulation with CRP (1 μg/mL) or thrombin (0.5 U/mL) was measured 47 days after cessation of niraparib or vehicle treatment (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Platelets were left resting or activated with indicated agonists and MFI of P-selectin and αIIbβ3 integrins was measured on platelets in whole blood isolated from niraparib- or vehicle-treated mice (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; multiple t tests were used. CRP, collagen-related peptide; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC.

Bone marrow HSPC counts and platelets recover after short-term niraparib treatment. (A) Time course of platelet counts in vehicle- and niraparib-treated mice (25 mg/kg). Mice were followed and platelet counts measured for 47 days after treatment cessation (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. (B) Absolute counts of HSPC populations 47 days after cessation of niraparib or vehicle treatment were quantified by flow cytometry using the panel outlined in supplemental Figure 2 (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (C) Platelet aggregation after stimulation with CRP (1 μg/mL) or thrombin (0.5 U/mL) was measured 47 days after cessation of niraparib or vehicle treatment (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Platelets were left resting or activated with indicated agonists and MFI of P-selectin and αIIbβ3 integrins was measured on platelets in whole blood isolated from niraparib- or vehicle-treated mice (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data are mean ± SD; multiple t tests were used. CRP, collagen-related peptide; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC.

Niraparib treatment increases MK DNA damage and MK maturation in mice

As PARP inhibition affects DNA repair,20 we next aimed to examine DNA damage accumulation in HSPCs after niraparib treatment. To probe the extent and specificity of niraparib-induced DNA damage, we analyzed phosphorylation of the histone protein H2AX, a common marker of DNA damage, in both HSCs and MkPs. Notably, after 3 days of niraparib treatment and preceding the increase in platelet counts, there was increased phosphorylated γH2AX in HSCs, CD41+ HSCs, and MkPs (Figure 5A). Few studies have directly addressed the role of DNA damage in MKs. However, MK development has been associated with DNA damage and repair,21,22 suggesting a connection between these processes. Furthermore, DNA damage of committed HSCs can promote MK differentiation via arrest in the G2 phase of the cell cycle.23 Probing γH2AX immunofluorescence in situ, we observed a higher proportion of γH2AX+ MKs and more foci per MK (Figure 5B) after niraparib treatment. To directly analyze DNA breaks in native MKs, we isolated bone marrow MKs from niraparib- and vehicle-treated mice and performed comet assays (Figure 5C). These assays showed significantly longer tail lengths, indicating increased DNA damage in MKs from niraparib-treated mice (Figure 5C). Together, our data demonstrate that 25 mg/kg niraparib treatment induced DNA damage in MKs.

Low-dose niraparib treatment leads to DNA damage in MKs and MkPs and enhances MK maturation. Mice were treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib or vehicle control. (A) γH2AX positivity in indicated HSPC populations in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. Gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2. (B) Representative widefield images of femoral cryosections derived from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (CD41, green; γH2AX, purple; scale bar, 20 μm). Quantification shows the percentage of femoral MKs that have either 0, 1 to 10, or >10 γH2AX foci in the nucleus; 100 MKs counted per femur (n = 3 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; multiple t tests. (C) Representative images of native MKs from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (left; green, SYBR gold; scale bars, 100 μm). MKs were isolated from femurs and the tail DNA (%) of at least 120 MKs per femur were analyzed across 3 replicates (3 femurs) per condition (n = 3 mice per group). Violin plots show distribution of all data points along with median and interquartile range; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Ploidy distribution in native MKs from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice after 3 and 11 days (n = 5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; ST-HSC, short-term HSC.

Low-dose niraparib treatment leads to DNA damage in MKs and MkPs and enhances MK maturation. Mice were treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib or vehicle control. (A) γH2AX positivity in indicated HSPC populations in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. Gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2. (B) Representative widefield images of femoral cryosections derived from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (CD41, green; γH2AX, purple; scale bar, 20 μm). Quantification shows the percentage of femoral MKs that have either 0, 1 to 10, or >10 γH2AX foci in the nucleus; 100 MKs counted per femur (n = 3 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; multiple t tests. (C) Representative images of native MKs from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (left; green, SYBR gold; scale bars, 100 μm). MKs were isolated from femurs and the tail DNA (%) of at least 120 MKs per femur were analyzed across 3 replicates (3 femurs) per condition (n = 3 mice per group). Violin plots show distribution of all data points along with median and interquartile range; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Ploidy distribution in native MKs from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice after 3 and 11 days (n = 5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 2-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; ST-HSC, short-term HSC.

In addition to changes in MK numbers, niraparib treatment also resulted in striking differences in MK ploidy from day 3 to day 11 (Figure 5D), with a shift toward high-ploidy MKs. These data further substantiate that despite increased DNA damage accumulation, MKs continued to mature and replicate DNA. Although MK ploidy is not directly causative of platelet production, higher-ploidy MKs with more cytoplasm are thought to largely contribute to platelet production.24 Collectively, these data indicate that inducing low levels of DNA damage in MKs promoted megakaryopoiesis, resulting in increased platelet production.

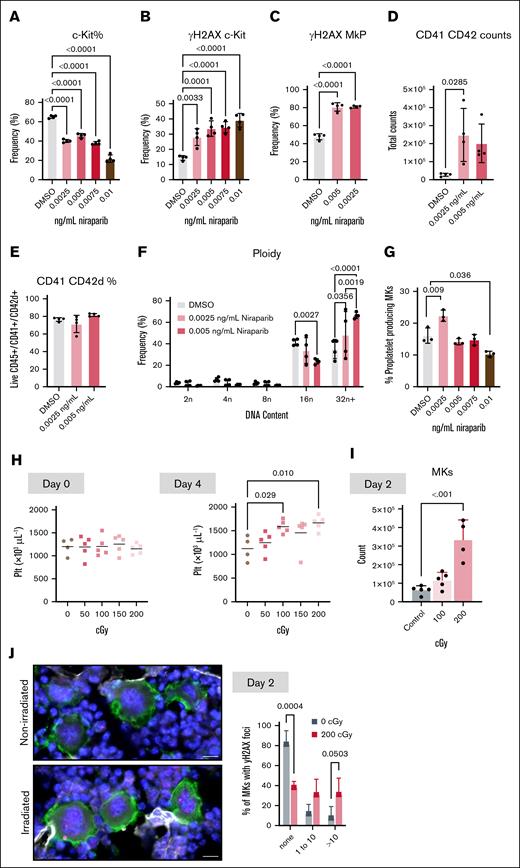

Niraparib treatment enhances MK differentiation and proplatelet production from bone marrow HSPCs in vitro

To rule out effects from secondary mediators, we performed in vitro experiments in which murine bone marrow HSPCs9,10 were treated with niraparib, and MK differentiation was assessed after 4 days in culture. A dose curve of low- to high-dose niraparib resulted in a progressive decrease in c-Kit+ cells (Figure 6A), similar to the in vivo trend observed with decreased short-term HSCs (Figure 3A). In addition, there was a concomitant increase in DNA damage, as assessed by γH2AX positivity (Figure 6B), in which higher doses of niraparib could be affecting cell viability. This is consistent with our in vivo data showing that higher doses of niraparib resulted in thrombocytopenia. Therefore, we chose to examine the effect of the lower niraparib doses on MK differentiation and maturation. As with the HSPCs, niraparib treatment significantly increased γH2AX levels in MkPs (Figure 6C). In addition, niraparib treatment resulted in significantly more HSPCs differentiating into (CD41/CD42d+) MKs (Figure 6D) without a change in viability (Figure 6E). Furthermore, consistent with in vivo data, there was a shift toward higher-ploidy MKs (Figure 6F). Last, we examined whether niraparib affected the capacity of MKs to make proplatelets in vitro. We treated mature MKs with a dose curve of niraparib, which revealed that low-dose niraparib significantly enhanced proplatelet production but decreased proplatelet production at high doses (Figure 6G; supplemental Figure 4). This finding is consistent with niraparib’s in vivo effect on platelet counts (Figure 1B,D) and suggests that in addition to increasing MK counts, niraparib may be directly enhancing platelet production from mature MKs. Together, these in vitro data substantiate that niraparib directly affects MK and platelet counts in vivo.

DNA damage can dose dependently enhance megakaryopoiesis in vitro and in vivo. HSPCs were isolated from bone marrow, niraparib was added at indicated doses, and cells were differentiated into MKs. (A-C) Frequency of (A) live progenitor cells (Live; CD45+ Lineage-negative ckit+ cells) (B), γH2AX+ progenitor cells and (C), γH2AX+ MkPs (CD41+) after niraparib treatment (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. Number of MKs (CD41/CD42d+) (D), MK viability (E), and MK ploidy distribution (F) after treatment of HSPCs with indicated doses of niraparib in vitro (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. (G) HSPCs isolated from murine bone marrow were differentiated into MKs. Indicated doses of niraparib were added to mature MKs on day 4 of culture and proplatelet formation (percent MKs making proplatelets) was quantified using images of live, nonadherent cells 24 hours after treatment (n = 3 mice per group). At least 250 MKs were counted per replicate. Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. (H-J) Mice were subject to gamma irradiation at indicated dosages and (H) platelet counts were measured at day 0 (left) and day 4 (right) (n = 4-5 mice per dose). (I) Murine bone marrow MKs (CD41/CD42d+) were quantified by flow cytometry 2 days after treatment with 0, 100, or 200 cGY (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. (J) Representative widefield images of femoral cryosections from control or irradiated mice (CD41, green; γH2AX, pink; scale bars, 20 μm). Quantification shows the percentage of femoral MKs that have either 0, 1 to 10, or >10 γH2AX foci in the nucleus of control or irradiated mice; 100 MKs counted per femur (n = 3 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; multiple t tests. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Plt, platelet.

DNA damage can dose dependently enhance megakaryopoiesis in vitro and in vivo. HSPCs were isolated from bone marrow, niraparib was added at indicated doses, and cells were differentiated into MKs. (A-C) Frequency of (A) live progenitor cells (Live; CD45+ Lineage-negative ckit+ cells) (B), γH2AX+ progenitor cells and (C), γH2AX+ MkPs (CD41+) after niraparib treatment (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. Number of MKs (CD41/CD42d+) (D), MK viability (E), and MK ploidy distribution (F) after treatment of HSPCs with indicated doses of niraparib in vitro (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. (G) HSPCs isolated from murine bone marrow were differentiated into MKs. Indicated doses of niraparib were added to mature MKs on day 4 of culture and proplatelet formation (percent MKs making proplatelets) was quantified using images of live, nonadherent cells 24 hours after treatment (n = 3 mice per group). At least 250 MKs were counted per replicate. Data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction used for multiple comparisons. (H-J) Mice were subject to gamma irradiation at indicated dosages and (H) platelet counts were measured at day 0 (left) and day 4 (right) (n = 4-5 mice per dose). (I) Murine bone marrow MKs (CD41/CD42d+) were quantified by flow cytometry 2 days after treatment with 0, 100, or 200 cGY (n = 4-5 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 1-way ANOVA with Šidák correction used for multiple comparisons. (J) Representative widefield images of femoral cryosections from control or irradiated mice (CD41, green; γH2AX, pink; scale bars, 20 μm). Quantification shows the percentage of femoral MKs that have either 0, 1 to 10, or >10 γH2AX foci in the nucleus of control or irradiated mice; 100 MKs counted per femur (n = 3 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; multiple t tests. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Plt, platelet.

Low-dose irradiation–induced DNA damage increases both MK and platelet counts in mice

Finally, to confirm that the increase in MK and platelet counts was not specific to PARPi but rather a general response to increased DNA damage, we subjected mice to a dose curve of ionizing radiation. Radiation dose dependently increased platelet counts after 4 days (Figure 6H). Similar to niraparib, 2 days after irradiation and preceding the increase in platelet counts, bone marrow MKs were significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6I), accompanied by an accumulation of DNA damage in the MKs of mice irradiated with 200 cGy (Figure 6J). These data reveal that in addition to niraparib, which prevents DNA repair, direct DNA damage by ionizing radiation also increases both MK and platelet counts in mice.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we showed that induction of DNA damage in vivo and in vitro, through treatment of mice and primary HSPCs with low levels of PARPis and irradiation, led to an increase in platelet counts. This increase in platelet counts was accompanied by elevated MK counts and increased DNA damage in MKs and MkPs. These results suggest that increased DNA damage accumulation promotes de novo megakaryopoiesis and further suggest that this pathway could be manipulated to promote MK differentiation and maturation.

These data demonstrate that moderate DNA damage stimulates megakaryopoiesis and platelet production. This challenges a conventional view that DNA damage predominantly impairs hematopoietic function, revealing instead that distinct biological mechanisms can operate at different DNA damage thresholds in specific cell types. We propose that moderate DNA damage may activate adaptive cellular responses that enhance MK maturation and platelet production. Indeed, hormesis refers to a biological phenomenon in which a low dose of a stressor stimulates a beneficial adaptive response, whereas a higher dose can be harmful, creating a biphasic dose response.25 It is thought that this adaptive reaction helps to moderate processes such as oxidative stress and inflammation levels and mitigate cellular senescence by allowing for tissue repair, restoring cellular homeostasis, and improving the body’s defense and adaptability.25 Notably, radiation hormesis is a well-known phenomenon.26,27 Human studies have shown that individuals exposed to occupational low-dose irradiation present with elevated platelet counts.28,29 More recently, it has been shown that low-dose irradiation induces a hormetic response that specifically upregulates lipid metabolism and increases lipid yield.30 A previous publication from our group showed that lipid biogenesis, specifically of polyunsaturated fatty acids, is essential for MK differentiation and maturation,9 creating an intriguing link between the hormetic response induced by DNA damage and the possibility of increased lipid metabolism.

Clinically, niraparib dosing is approved up to 300 mg once daily; our experiments in mice revealed that higher doses of niraparib induced both thrombocytopenia and anemia (Figure 1B), consistent with patient data. The narrow window of PARPi dosage that increased platelet production, defined by the balance between insufficient DNA damage to elicit response and excessive damage inducing thrombocytopenia, may account for the relative scarcity of platelet count alterations reported in clinical settings. Furthermore, patients with cancer treated clinically with PARPis have significant comorbidities that may confound results and independently affect platelet counts. As such, there is currently insufficient data to examine whether low-dose PARPis increased platelet counts in patients. This highlights the critical need for using carefully titrated, lower doses of PARPis and analogous agents in both in vitro and in vivo experimental settings to examine their stimulatory potential on megakaryopoiesis while minimizing deleterious hematopoietic outcomes.

Although we found that PARPi administration can be a potent inducer of platelet production, it is important to consider that the clinical application of strategies involving deliberate induction of DNA damage to increase platelet counts necessitates rigorous evaluation of associated risks. Notably, prolonged exposure to PARPis has been associated with secondary myelodysplastic syndromes and leukemic transformation.31 However, this risk may not be prevalent in patients who are given only a low-dose and short-term exposure to PARPis. The evaluation of PARPi-mediated platelet augmentation at this stage remains premature due to the heightened potential for adverse hematologic outcomes. However, low-dose PARPis could offer therapeutic options for treating thrombocytopenia in specific contexts in which platelet transfusions are not viable, such as in patients with ITP, in the future.

Although safety concerns currently limit immediate therapeutic application, our in vitro data suggest potential utility in emerging in vitro platelet production systems.32 Low-dose niraparib treatment of HSPCs could enhance these manufacturing platforms by increasing the number of MKs available for bioreactor processing into platelets, which have no DNA. Recent clinical-scale achievements, including the successful iPLAT1 trial using turbulent flow bioreactors to produce 100 billion induced pluripotent stem cell-derived platelets,33 support the feasibility of such integrated approaches. Crucially, our data also demonstrate that the platelets generated in the presence of PARPis and low-dose radiation remain functional, supporting their potential for clinical use.

Although niraparib and olaparib both increased platelet counts in our murine models, the magnitude of the response differed. We were interested in this difference and found that these compounds are structurally distinct with divergent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. Specifically, clinical pharmacological data indicate that olaparib exhibits lower oral bioavailability and reduced bone marrow penetration relative to niraparib.34 These differences, specifically the reduced bone marrow penetration seen with olaparib, may explain the variances observed between niraparib and olaparib on platelet counts.

In summary, our results reveal that moderate DNA damage acts as a potent driver of megakaryopoiesis, polyploidization, and subsequent platelet production in vivo. Low-dose PARPis may, if safety concerns surrounding secondary effects are appropriately addressed, offer therapeutic options for treating thrombocytopenia in specific contexts; for example, as a bridge therapy in patients for whom the use of platelet transfusions is not an option, such as in patients with ITP. Collectively, these data uncover a previously underappreciated link between MKs and DNA damage and present a novel mechanism governing platelet production in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R03DK124746 and R01DK139341 (K.R.M.) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL151494 (K.R.M.), K99HL175037 (M.N.B.), and R35HL161175 (J.E.I.) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). R.H.B. is the recipient of a 2023 Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society (HTRS) Mentored Research award from the HTRS, supported by an educational grant from CSL Behring. M.N.B. is the recipient of fellowships from the American Society of Hematology (ASH; ASH Restart Award) and the American Heart Association (23POST1011433). K.R.M. is the recipient of an Innovative Project Award from the American Heart Association (24IPA1274573). V.C. is the recipient of an ASH Scholar Award. S.P. is supported by NIH, National Cancer Institute (NCI) U54 grant 1U54CA274516 and NCI specialized programs of research excellence grant 2P50CA165962. L.F.Z.B. was supported by NIH grants CA258386, HL174789, HL172961, the Department of Defense (BM230053), the American Cancer Society (133856-RSG), and the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University in St. Louis.

Authorship

Contribution: R.H.B., A.P.S., C.P., V.C., E.C., S.B., M.N.B., I.C.B., J.K., D.H.L., E.W., and J.T. performed experiments, and interpreted and analyzed data; R.H.B., V.C., A.P.S., C.P., M.N.B., J.K., L.F.Z.B., S.P., J.E.I., and K.R.M. conceptualized experiments and research ideas; V.C., R.H.B., C.P., L.F.Z.B., I.C.B., J.E.I., and K.R.M. wrote and edited the manuscript; V.C., L.F.Z.B., J.E.I., and K.R.M. responded to reviewer comments; and S.P., J.E.I., and K.R.M. funded research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.E.I. has a financial interest in and is a founder of Stellular Bio, a biotechnology company focused on making donor-independent platelet-like cells at scale, and SpryBio, a biotechnology company focused on using shelf-stable platelets to treat osteoarthritis; and Boston Children's Hospital manages the interests of J.E.I. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for I.C.B. is Centre for Immunobiology, Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom.

Correspondence: Kellie R. Machlus, Vascular Biology Program, Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, Karp Research Building, 1 Blackfan Cir, Room 11.214, Boston, MA 02115; email: kellie.machlus@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

V.C. and R.H.B. contributed equally to this study.

Publication-related are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Kellie R. Machlus (kellie.machlus@childrens.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Low-dose niraparib treatment enhances megakaryopoiesis. (A) HSPC counts in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. Gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2. (B) Representative images of femoral cryosections from vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice (CD41, green). Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (blue; scale bars, 1000 μm; inset scale bars, 200 μm). (C-D) MK counts (C) and area (D) in vehicle- or niraparib-treated mice were quantified in femoral cryosections (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. (E) MK/platelet reporter mice (VWF–green fluorescent protein [GFP]) were treated with 25 mg/kg niraparib or vehicle for 7 days, and 2-photon intravital microscopy of the calvaria was performed. Representative images show MKs (cyan) and vasculature (magenta; labeled using Evans Blue; scale bars, 20 μm). (F) Live MKs were quantified by size and GFP signal (n = 4 mice per group). Data shown as mean ± SD; unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; ST-HSC, short-term HSC; VWF, von Willebrand factor.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025017375/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-017375-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1770824016&Signature=gOICJpAiiLA2YmDyKREGoF2oMANuMDI0fv3EwAzdkTSE8m48B6d9Fm0lKdRKlqzQyUEFCmY7aKWxwxIeiFFAPjIwq3pXXrZyQ62g8ch~5TPZgD8gfdC3o9ZAHP1DQpgevqVv6q9XDU26QVEK4aUI2-yfVe~7eDeznwZoxCDs6e7l949WK8Z6fFD-WnMiMIe1eGrNqirDNZnpmF3Cna7sZ2ssL--VIzS16WioAwAswBB3fD0IVHgFaOgc~MZXunGnWcOw-OctXzLz0WfigmGdX6bh0QPVLi7rKBlsliiBsBo-UNDXXpfxJNnNCuwsEsG0H~peqUXlJsjudrIqE6gzdQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)