Historically, sickle cell disease (SCD) has been overshadowed by progress in other hematologic disorders, but recent advances are reshaping its clinical and research landscape. Despite SCD reducing life expectancy by >20 years even with optimal care, transformative initiatives are fostering hope for improved outcomes. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) established the ASH Research Collaborative Sickle Cell Disease Research Network as a comprehensive program to revolutionize SCD research in the United States. This Network comprises a collection of innovative, research-focused cooperative sites and a robust Data Hub that aggregates extensive real-world data sets to enhance clinical insights and streamline research designs. Community advisory boards at both local and national levels ensure that the perspectives of individuals living with SCD guide research priorities. This report includes an overview of the initial demographics, such as the number of records, encounters, laboratory data, prescriptions, years of follow-up, and comorbidities per patient, within the context of the ASH Research Collaborative Sickle Cell Disease Research Network. These coordinated efforts are poised to significantly transform the landscape of SCD care, and this report details the initiative’s mission, history, achievements to date, and its promising trajectory toward improving the lives of individuals affected by this chronic condition.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is among the most common of the clinically severe inherited human diseases, estimated to affect almost 8 million people worldwide, including ∼100 000 individuals in the United States.1 Life expectancy of individuals with SCD is shortened by at least 20 years, even with optimal clinical care.2 Despite significant advances in understanding the science of globin gene regulation and the pathophysiology of SCD, translating these findings into therapeutics has been frustratingly slow.3

Challenges in SCD research

For nearly 2 decades, hydroxyurea was the sole US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapeutic for SCD. In recent years, the FDA has approved l-glutamine,4 crizanlizumab,5 and voxelotor6 for the chronic treatment of this disease; however, crizanlizumab is no longer available in Europe and the manufacturer of voxelotor recently removed it from the worldwide market. Currently, there are at least 28 new therapeutics for SCD in various stages of development. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is effective and highly curative, but its use is limited to a small subset of patients in high-resource settings.7,8 Two gene therapy treatments were FDA approved in 2023, yet both of these “transformative” therapies require patients to undergo cost-prohibitive ex vivo hematopoietic stem cell modifications and myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant which limit the speed of uptake both in the United States and worldwide.9,10

The progress made on industry investment and the number of ongoing therapeutic trials in SCD may be affected by the withdrawal of new treatments from the market.11 In addition to traditional clinical trials aimed at developing new therapeutic options, there remains a critical need for research that generates evidence to guide screening and prevention, implementation of clinical care guidelines, and implementation of current and newly approved therapies. Such research is essential to addressing persistent disparities in health outcomes, life expectancy, and quality of life for individuals living with SCD.

There is strong evidence supporting the urgent need for more robust research in SCD. The 2016 American Society of Hematology (ASH) SCD guideline recommendations12 were, for the most part, conditional, citing a “paucity of data and high-quality evidence.” In 2020, the National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (NASEM)13 published its strategic plan and blueprint to address SCD. In the report, 2 of the 8 recommendations call on private and public funders to establish and fund a robust research agenda and to strengthen the evidence base to close gaps in care delivery. The published ASH Sickle Cell Research Priorities4 identified research topics and unanswered questions to be addressed to move the field forward, most of which require the capacity and vision afforded by the ASH Research Collaborative (ASH RC).

A review of non–industry-sponsored clinical trials conducted through ClinicalTrials.gov in September 2024 identified 239 active clinical research studies, underscoring substantial academic interest in SCD research. Although the sheer volume and interest in SCD research is significant, most of these projects (72%) are single-institution studies, with only 20% being conducted at ≥3 clinical sites. Industry is unlikely to undertake this type of research; therefore, the onus is on those who care for and treat people living with SCD to advance this science.

ASH recognized that SCD was an area of substantial need and organized a summit that consisted of representatives from academia, patient groups, governmental partners, and industry. The participants felt that progress was being hampered by a lack of research collaboration, a registry, and research funding that together could be addressed by a national Sickle Cell Disease Clinical Trials Network.

Turning necessity into action

In 2017, the ASH launched the ASH RC to promote partnerships and enable large-scale collaborative research aimed at improving outcomes for people with blood disorders, with an initial focus on SCD and multiple myeloma. To address the unique challenges of SCD research, the ASH RC established the SCD Research Network, which was created to overcome barriers in conducting clinical trials for SCD. These efforts included the following: (1) addressing shortages of coordinated teams of primary investigators at clinical trial sites; (2) establishing and enhancing access to a centralized data repository; and (3) ensuring that studies are less redundant, more efficient, easier to scale, and more cost effective. It was also recognized that the perspectives of individuals living with SCD had historically been underrepresented in the development and prioritization of clinical trials, which contributed to difficulties with participant enrollment.14,15 In response, the Network made a commitment to educating patients about clinical trials and actively involving them in the research process, from the earliest stages of trial design to study completion and the dissemination of results.

To meet its mission, the objectives for the Network were to accelerate and optimize the conduct of SCD clinical trials through the following:

Forging new relationships with patients to increase their understanding of clinical trials and trust in SCD researchers;

Focusing on the research opportunities that hold the most promise for patients;

Matching trial sponsors with research sites;

Facilitating the recruitment of eligible patients;

Ensuring optimally designed trials and an efficient, coordinated approach to enrollment;

Eliminating inefficiencies by using a centralized data repository and institutional review board (IRB);

Integrating real-world hematology data into a unified database (a “Data Hub”); and

Establishing both local and national community advisory boards (CABs; NCAB) to ensure research is designed to meet the needs of people affected by SCD.

A network in evolution

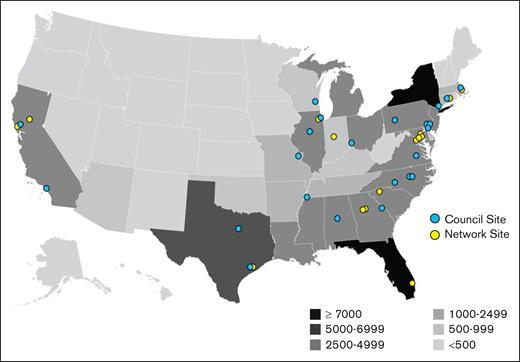

The ASH RC defined a specific structure and set of requirements for applicants to be considered for recognition and funding to be part of the Network. The Network was originally organized using a consortia model with 20 primary sites that each had several satellite sites. This consortia model was modeled based on an HIV research community and the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health.15,16 However, it proved too difficult to maintain a connection with the satellite sites as initially conceived due to challenges involved with intersite contracting. Consequently, the Network was redesigned so that each site has direct participation and contract with the ASH RC. The minimum requirement to be a Network site is that each site must agree to enter data into the ASH RC’s real-world data program called the Data Hub. A subset of Network sites makes up the Network Council which acts as the Network’s steering committee. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of 50 Network sites throughout the United States in a way that overlaps with the geographic distribution of people living with SCD. A full list of SCD Research Network sites can be found at https://www.ashresearchcollaborative.org/sickle-cell-disease-research-network/.

Alignment of patients and sites. Geographic distribution of people with SCD. Overlaid on the map are the locations of current sites with affiliation with the ASH RC SCD. Adapted from Hassell.17

Alignment of patients and sites. Geographic distribution of people with SCD. Overlaid on the map are the locations of current sites with affiliation with the ASH RC SCD. Adapted from Hassell.17

Network sites collectively self-reported caring for ∼37 800 people with SCD, representing more than one-third of the total US population affected by the disease.

Network structure and governance

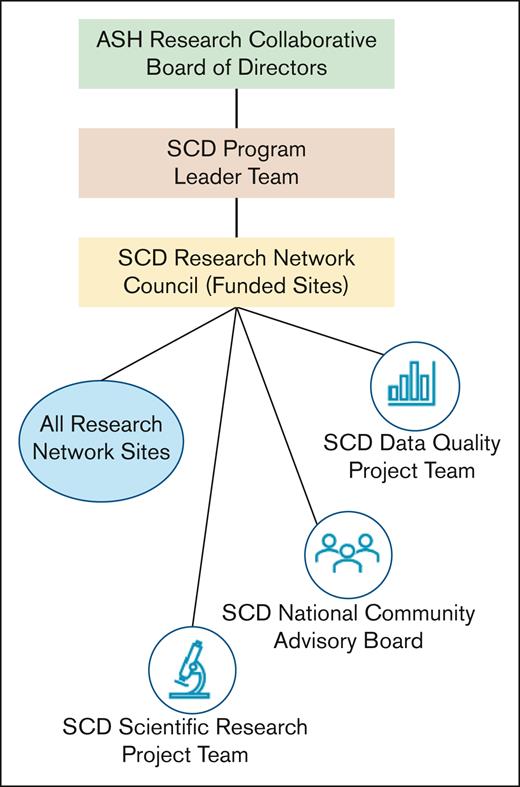

The SCD Research Network's organizational structure was designed to enhance coordination, increase efficiency, and bolster engagement among leaders and community members Figure 2. Individuals across these groups were selected based on their specialized expertise, with a particular focus on fostering a new generation of ASH RC leaders. Individuals with historical knowledge are also included to help circumvent previously encountered challenges.

The ASH RC Board provides strategic oversight for all ASH RC activities, and the SCD Program Leader Team is composed of the appointed Chairs for the Project Teams and the National CAB. The role of this Leadership Team is to provide timely review of strategic and scientific business development opportunities in between Council meetings and ensure all program committee activities support the goals and objectives of the overall Network. The SCD Program Leader Team reports directly to the ASH RC Board of Directors.

The Research Network Council acts as the Network steering committee. They set priorities and advocate for research and quality improvement, establishing the strategic direction with overall supervision of research, community activities, and data implementation. Each Council site cares for both pediatric and adult individuals, so a “single site” might represent a partnership between pediatric and adult hospitals. Principal Investigators (PIs) at Council sites serve 3-year terms and may reapply for an additional 3-year term, provided their site is also reapplying for Council membership. However, reappointment is competitive, as they must compete alongside other prospective programs. After our recent competitive renewal, the Council expanded from 20 to 23 individual sites. Each site is required to participate in industry-sponsored research, engage in collaborative studies, contribute data to the Data Hub, and establish a local CAB.

Each Council site is required to maintain adequate clinical and research infrastructure, including dedicated staff and an institutional commitment to ensure organizational stability and capacity to meet the Council’s objectives. There are 2 principal investigators (PIs) at each site who are responsible for the activities and performance and serve as the primary scientific and administrative representative of their site. A qualified coordinator is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations and is required to have relevant management and clinical research experience.

The ASH RC provides annual infrastructure funding to ensure each Council site’s PI is fulfilling their core responsibilities. These include the following:

Submitting electronic health record (EHR) data to the Data Hub, quarterly;

Engaging with the SCD patient community through the participation in the CABs;

Developing and conducting investigator-initiated studies; and

Enrolling patients in industry-sponsored clinical research studies.

There are 3 project teams that report to the SCD Research Network Council with specific charges for advancing the Network’s mission and research agenda.

The SCD Program Leader Team consisted of the appointed Chairs for the Project Teams and the NCAB. The role of this Leadership Team is to provide timely review of strategic and scientific business development opportunities in between Council meetings and ensure all program committee activities support the goals and objectives of the overall Network.

The Data Quality Project Team develops and executes the program data quality: strategy monitoring data quality, identifying and executing priorities, and advising on both sources of real-world data and data acquisition methods. The Data Quality Project Team is also responsible for developing and testing computable phenotypes to generate high-value analytic data sets. The group advises on alignment with national data and medical informatics standards, obtains input and feedback on data quality needs and priorities from the Research Network, and consults for the Scientific Research Project Team regarding feasibility of Data Hub research proposals. This Team also creates resources that describe Data Hub data quality for researchers and statisticians.

The Scientific Research Project Team develops and evaluates prospective, real-world data–based research proposals for external industry, foundation, and federal funding that are investigator-initiated. Their input solidifies study design for industry-sponsored study protocols and will be used to allow and approve research proposal applications that request use of Data Hub data and select secondary reviewers for abstract and manuscript development. As the field evolves, the Committee’s role includes prioritizing research topics.

The SCD National Community Advisory Board (NCAB) represents the values, research priorities, and concerns of the local CAB. The NCAB is made up of representatives elected at local SCD Research Network sites, including those living with SCD, their caretakers, and advocates. It has joint leadership consisting of a patient or caregiver from the NCAB and a PI lead. The National CAB is charged with fostering collaborative discussions on research priorities and study design to address enrollment and retention challenges (protocol reviews), curating a centralized library of vetted educational materials on clinical research ensuring medical and cultural relevancy, and serves as a collaborative research partner, providing community-driven insights throughout the research process.

Community engagement and patient-centered research

From its inception, the ASH RC prioritized patient and caregiver engagement as a foundational strategy for achieving research success. The Network was intentionally designed to embed community partnership at its core, fostering trust and sustained collaboration with those directly affected by SCD. Meaningful progress in SCD research is not possible without the active participation of individuals living with the disease and their families. Accordingly, the Network has consistently operated in partnership with the community, rather than for the community, to ensure research is informed by lived experiences and aligned with patient priorities. The SCD Community includes individuals living with the disease and their families and caregivers. Members of the Community participate in the Network through CABs. Each Council site maintains a local CAB that meets regularly to advise PIs, support bidirectional communication, and inform patient-centered research strategies. In addition, each local CAB elects 2 representatives to serve in the NCAB, which plays a central role in shaping national research priorities and guiding Network activities. The NCAB fulfills this role through the following:

Participating in training activities to enhance knowledge related to clinical trial design and protocol review;

Facilitating collaborative dialogue on research priorities and study designs to identify and mitigate barriers to participant enrollment and retention;

Curating and disseminating a centralized library of culturally relevant, evidence-based educational materials to enhance understanding of the clinical research process;

Developing tools to support shared decision-making between patients and clinicians, including resources to optimize the informed consent process;

Promoting transparency and accountability through clear communication of research findings and study outcomes to the broader community; and

Increasing community access to timeline and accurate information regarding opportunities for clinical research participation.

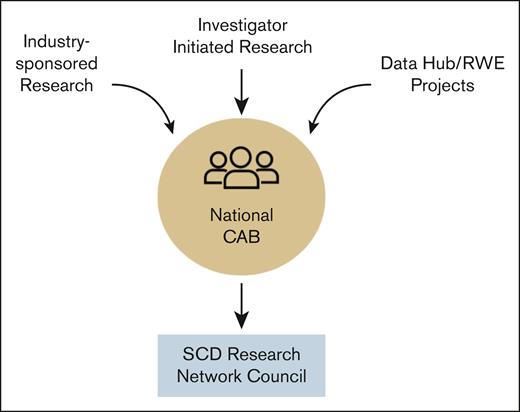

No research study is performed through the Network without first discussing with the NCAB members as illustrated in Figure 3. In general, NCAB members are not compensated for their participation. However, funded opportunities, such as those from industry-sponsored research, do come with some compensation depending on the time and effort involved. Compensation averages ∼$250 per member per session.

Flow of research through the NCAB to aid Network Council prioritization of industry- and investigator-initiated research and RWE project leveraging the Data Hub. RWE, real-world evidence.

Flow of research through the NCAB to aid Network Council prioritization of industry- and investigator-initiated research and RWE project leveraging the Data Hub. RWE, real-world evidence.

The ASH RC Data Hub

One advantage of the Network is its integration with the ASH RC Data Hub.18 The Data Hub is a comprehensive national SCD registry that imports clinical information from EHRs on individuals cared for at Network sites. The Data Hub receives limited data set information from participating sites under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule19 (45 CFR Section 164.514(e)). A HIPAA Privacy Board (Western Copernicus Group [WCG] IRB) reviewed and approved a waiver of authorization in accordance with 45 CFR Section 164.512(i),20 determining that the use and disclosure of limited data set for research involves no more than minimal risk to privacy and that obtaining individual patient authorization would not be practicable. As a result, sites are not required to obtain individual consent for data submission, provided that data use agreements are in place and appropriate privacy safeguards are maintained. This regulatory framework enables the aggregation of high-quality real-world data from EHRs to support research, quality improvement, and real-world evidence generation in hematology.

The protection of data collected in the Data Hub is a central priority of the Network. All data are stored on secure servers and managed in accordance with the highest standards of research ethics and data privacy regulations, including HIPAA Privacy Rule and relevant IRB oversight.21 Oversight is provided by the WCG, which serves as the designated IRB and HIPAA Privacy Board. Participating sites are required to obtain IRB approval before submitting patient data to the Data Hub. When required by participating site’s policy, sites may receive local IRB approval to rely on WCG’s oversight for participation in this program. The WCG reviewed and approved the Data Hub protocol in compliance with the Revised Common Rule.

To support scalability in both size and scope, the program leverages modern informatics approaches to create analytic data sets using EHR-standardized coding systems, such as International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms (SNOMED), Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), RxNorm, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT). Network sites are required to submit updated, cumulative data at least quarterly, with recorded events extending back to 2015.

The Data Hub can support research in several critical ways:

Observational, retrospective analyses (including studies of the natural history of SCD);

Identifying and studying specific cohorts of interest (eg, chronic kidney disease);

Support clinical trial design by providing data for sample size and effect size calculations;

Assisting sites in identifying individuals who would be eligible subjects for potential trials;

Developing contemporaneous control groups to support single-arm trials.

Assessing the long-term safety of newly approved therapeutics;

Performing comparative effectiveness studies;

Conducting prospective evidence-generation projects;

Promoting collaborative research projects across the Network; and

Assessing the safety, efficacy, and outcomes of disease-modifying therapies.

Participating sites access their confidential data through a secure dashboard. Furthermore, they can submit research proposals to use deidentified, aggregated data compiled from all contributing sites. Given the limited availability of large-scale real-world data in SCD and considering the difficulty in accessing large-scale real-world clinical data in SCD, the Data Hub represents a valuable resource for generating insights to inform therapeutic development, refine research hypotheses, and support improvements in clinical care delivery and patient outcomes.

To showcase the potential of the information collected by the Data Hub to the clinical and research community, an analysis of the data was performed. The goals of the analysis were the following: (1) to provide an appreciation for the scope and breadth of data available in the Data Hub; (2) to evaluate the demographics of the individuals in the Data Hub to inform comparisons with other US-based registries and research; and (3) to explore the extent and potential for longitudinal analyses using the Data Hub.

At each Data Hub site, individuals were selected based on having a documented diagnosis code of SCD in their EHR, as identified using EHR data and a validated list of diagnostic codes. To be included in the analysis, it was necessary for a physician at the site to attest to the individual’s SCD diagnosis. In addition, the individual had to be considered “active” during at least 1 calendar year. For the Data Hub, active is defined as having ≥1 records of an inpatient, emergency department, or outpatient encounter during the calendar year. For eligible individuals, records from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2024, were included.

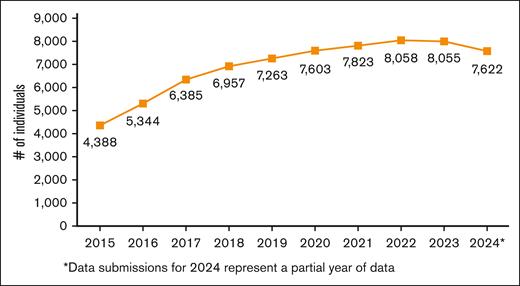

There were 23 580 total active individuals in the Data Hub, and this analysis included the 10 412 with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis. The number of active individuals in the Data Hub has steadily increased from 4388 in 2015 to 8055 in 2023 (Figure 4). The analysis included 2024 data, but because of a data-processing lag that affects availability for data transmissions, it is anticipated that the number will increase.

Number of active individuals with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis in the Data Hub for the years shown.

Number of active individuals with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis in the Data Hub for the years shown.

During the time period from 2015 to 2024, the 10 412 individuals with physician-attested SCD diagnosis had a total of 120 792 inpatient records, 75 710 emergency department records, 2 075 928 outpatient records, 45 317 754 laboratory and clinical measurement records, and 5 992 470 prescription records. Extensive work is ongoing to understand site variations in how codes and records are developed and validating code sets to enable future reports that can include events numbers instead of records, for example, the number of inpatient visits vs encounter records with an inpatient code. The specific number of records by SCD diagnosis type is included in Table 1.

Number of encounter, laboratory, and prescription record counts by calendar year

| Year . | Inpatient encounter records . | Emergency room encounter records . | Outpatient encounter records . | Laboratory values/clinical measurement records . | Prescription records . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 9 604 | 5 356 | 145 324 | 1 818 174 | 314 616 |

| 2016 | 10 768 | 6 259 | 163 141 | 2 164 445 | 407 310 |

| 2017 | 11 888 | 7 609 | 186 179 | 4 294 161 | 526 376 |

| 2018 | 12 409 | 7 872 | 181 190 | 4 627 432 | 575 087 |

| 2019 | 13 043 | 7 695 | 189 180 | 5 028 447 | 709 482 |

| 2020 | 10 801 | 6 513 | 207 066 | 4 937 045 | 602 368 |

| 2021 | 13 270 | 8 037 | 248 626 | 5 602 974 | 693 927 |

| 2022 | 14 206 | 8 724 | 261 366 | 5 778 055 | 782 581 |

| 2023 | 13 665 | 9 800 | 273 847 | 6 076 895 | 803 791 |

| 2024∗ | 11 138 | 7 845 | 220 009 | 4 990 126 | 576 932 |

| Total | 120 792 | 75 710 | 2 075 928 | 45 317 754 | 5 992 470 |

| Year . | Inpatient encounter records . | Emergency room encounter records . | Outpatient encounter records . | Laboratory values/clinical measurement records . | Prescription records . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 9 604 | 5 356 | 145 324 | 1 818 174 | 314 616 |

| 2016 | 10 768 | 6 259 | 163 141 | 2 164 445 | 407 310 |

| 2017 | 11 888 | 7 609 | 186 179 | 4 294 161 | 526 376 |

| 2018 | 12 409 | 7 872 | 181 190 | 4 627 432 | 575 087 |

| 2019 | 13 043 | 7 695 | 189 180 | 5 028 447 | 709 482 |

| 2020 | 10 801 | 6 513 | 207 066 | 4 937 045 | 602 368 |

| 2021 | 13 270 | 8 037 | 248 626 | 5 602 974 | 693 927 |

| 2022 | 14 206 | 8 724 | 261 366 | 5 778 055 | 782 581 |

| 2023 | 13 665 | 9 800 | 273 847 | 6 076 895 | 803 791 |

| 2024∗ | 11 138 | 7 845 | 220 009 | 4 990 126 | 576 932 |

| Total | 120 792 | 75 710 | 2 075 928 | 45 317 754 | 5 992 470 |

Data submissions for 2024 represent a partial year of data.

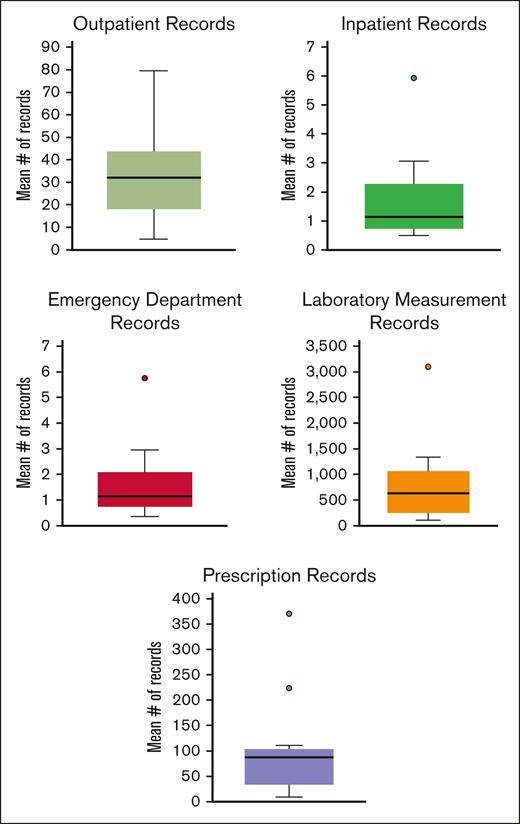

The inclusion of multiple institutions in the Data Hub provides opportunities to explore differences in care and the impact of those differences on outcomes. Looking at records from 2023, there is evidence of variability across the sites’ average number of records per person. For inpatient records, the average number of site records per person at the 25th percentile was 0.7 records in 2023 vs the 75th percentile which had an average of 2.2 records per person. For laboratory measurements, the site at the 25th percentile had an average of 270.8 records per person, and the site at the 75th percentile had an average of 1022.9 records per person. These variations likely included multiple factors, including case mix, the services provided by the institution in terms of outpatient, pharmacy, laboratory services, and how those are entered into their medical record. Box and whisker plots looking at the distribution in the mean number of records per institution are displayed in Figure 5.

Mean number of records per individual in 2023 across Data Hub sites by record type. Note that the y-axis scales vary substantially for the different record types.

Mean number of records per individual in 2023 across Data Hub sites by record type. Note that the y-axis scales vary substantially for the different record types.

Overall, the Data Hub contains extensive clinical data on a large population of individuals with SCD. Ongoing work to expand, refine, and validate code sets and clinical phenotypes will provide substantial opportunities to explore the care received by individuals with SCD and health outcomes.

This analysis included data from the 14 institutions with individuals with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis. These institutions are large, academic medical centers primarily located in major population centers. Therefore, there is the potential that the distribution of demographic and disease characteristics in this population may differ from other population-based resources and/or other studies. Over time, as additional sites are added, the intent is that those included will be generalizable to all individuals living with SCD in the United States. Sites in the Data Hub are asked to self-identify whether they are a pediatric site (primarily care for patients aged <18 years), an adult site (primarily care for patients aged >18 years), or a life span site (care for patients of all ages). Among the sites contributing individuals, 6 are pediatric, 4 are adult, and 4 are life span sites. Currently, the population is 42% pediatric, 52% female, 97% Black or African American, and 9% Hispanic. The most common type of SCD is hemoglobin SS (HbSS), which was reported for 65% of individuals, and the next most common is HbSC reported for 25% of individuals (Table 2). Comparison with the smaller cohort reported by the Center for Disease Control Sickle Cell Data Collection newborn screening program found that they had 57% of people with HbSS or HbS/β0 compared with 67% of individuals in the Data Hub cohort (Table 2; a study by Kayle et al22). Therefore, the demographics of this group of patients should be taken into consideration when comparing distributions from the Data Hub with other population-based data sources.

Number and percentage of individuals by demographic variables, stratified by physician-attestation status

| . | Individuals with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis, n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total population | 10 412 |

| Age on 31 December 2024, y | |

| <18 | 4 393 (42) |

| 18 to <26 | 2 027 (19) |

| ≥26 | 3 992 (38) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 5 418 (52) |

| Male | 4 994 (48) |

| Race | |

| Data provided | |

| Black/African American | 9 419 (97) |

| White | 211 (2) |

| Asian | 42 (<1) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 9 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (<1) |

| Missing | 729 (7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Data provided | |

| Hispanic | 953 (9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 9 181 (91) |

| Missing | 278 (7) |

| Sickle cell type | |

| HbSS | 6 782 (65) |

| HbS/β0 | 251 (2) |

| HbSC | 2 602 (25) |

| HbS β+ | 669 (6) |

| Other type | 108 (1) |

| Type of sites | |

| Pediatric only | 5 285 (51) |

| Adult only | 2 703 (26) |

| Life span | 2 424 (23) |

| . | Individuals with a physician-attested SCD diagnosis, n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total population | 10 412 |

| Age on 31 December 2024, y | |

| <18 | 4 393 (42) |

| 18 to <26 | 2 027 (19) |

| ≥26 | 3 992 (38) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 5 418 (52) |

| Male | 4 994 (48) |

| Race | |

| Data provided | |

| Black/African American | 9 419 (97) |

| White | 211 (2) |

| Asian | 42 (<1) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 9 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (<1) |

| Missing | 729 (7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Data provided | |

| Hispanic | 953 (9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 9 181 (91) |

| Missing | 278 (7) |

| Sickle cell type | |

| HbSS | 6 782 (65) |

| HbS/β0 | 251 (2) |

| HbSC | 2 602 (25) |

| HbS β+ | 669 (6) |

| Other type | 108 (1) |

| Type of sites | |

| Pediatric only | 5 285 (51) |

| Adult only | 2 703 (26) |

| Life span | 2 424 (23) |

The Data Hub currently includes 10 years of data with the opportunity for continued follow-up. There are 2 cohorts of individuals that will be of unique interest to researchers. Among the 10 412 individuals, there are 2626 individuals with 10 years of follow-up and an additional 2186 individuals with 8 or 9 years of follow-up. This is a robust cohort for long-term analysis of outcomes. A challenge of data collection efforts that are started based on calendar time is that the care and outcomes that happened before inclusion into the study are unknown or the data are incomplete. The Data Hub includes 1484 individuals whose data in the Data Hub begin when they were younger than 1 year. For this cohort, researchers will have the ability to follow them from infancy to get a full picture of the care received and health outcomes experienced. Table 3 provides the characteristics of 3 distinct cohorts within the Data Hub. The first is those with 10 years of follow-up, the second is those with continuous follow-up (ie, they are active in all years from their first to last year included in the Data Hub), and the third reveals individuals currently in the Data Hub who have data for 2023 or 2024.

Number and percentage of individuals by demographic characteristics by follow-up attributes

| . | Total population, n (%) . | Individuals with 10 years of follow-up, n (%) . | Individuals with consecutive follow-up, n (%) . | Individuals who were active in 2023 or 2024, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 10 412 | 2626 | 8228 | 8481 |

| Age, y | ||||

| <12 | 2 662 (26) | 323 (12) | 2 296 (28) | 2 400 (28) |

| 12 to <18 | 1 731 (17) | 711 (27) | 1 391 (17) | 1 520 (18) |

| 18 to <30 | 2 767 (27) | 748 (28) | 2 100 (25) | 2 150 (25) |

| ≥30 | 3 252 (31) | 844 (32) | 2 441 (30) | 2 411 (28) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 5 418 (52) | 1 416 (54) | 4 289 (52) | 4 416 (52) |

| Male | 4 994 (48) | 1 210 (46) | 3 939 (48) | 4 065 (48) |

| Type of site | ||||

| Pediatric | 4 446 (42) | 1 325 (50) | 3 611 (44) | 3 827 (45) |

| Adult | 2 703 (26) | 282 (11) | 2 033 (25) | 2 105 (25) |

| Life span | 3 263 (31) | 1 019 (39) | 2 551 (31) | 2 549 (30) |

| Sickle cell type | ||||

| HbSS | 6 782 (65) | 1 764 (67) | 5 473 (67) | 5 530 (65) |

| HbS/β0 | 251 (2) | 68 (3) | 203 (2) | 212 (2) |

| HbSC | 2 602 (25) | 625 (24) | 1 954 (24) | 2 105 (25) |

| HbS β+ | 669 (6) | 146 (5) | 506 (6) | 550 (6) |

| Other type | 108 (1) | 23 (1) | 92 (1) | 84 (1) |

| . | Total population, n (%) . | Individuals with 10 years of follow-up, n (%) . | Individuals with consecutive follow-up, n (%) . | Individuals who were active in 2023 or 2024, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 10 412 | 2626 | 8228 | 8481 |

| Age, y | ||||

| <12 | 2 662 (26) | 323 (12) | 2 296 (28) | 2 400 (28) |

| 12 to <18 | 1 731 (17) | 711 (27) | 1 391 (17) | 1 520 (18) |

| 18 to <30 | 2 767 (27) | 748 (28) | 2 100 (25) | 2 150 (25) |

| ≥30 | 3 252 (31) | 844 (32) | 2 441 (30) | 2 411 (28) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 5 418 (52) | 1 416 (54) | 4 289 (52) | 4 416 (52) |

| Male | 4 994 (48) | 1 210 (46) | 3 939 (48) | 4 065 (48) |

| Type of site | ||||

| Pediatric | 4 446 (42) | 1 325 (50) | 3 611 (44) | 3 827 (45) |

| Adult | 2 703 (26) | 282 (11) | 2 033 (25) | 2 105 (25) |

| Life span | 3 263 (31) | 1 019 (39) | 2 551 (31) | 2 549 (30) |

| Sickle cell type | ||||

| HbSS | 6 782 (65) | 1 764 (67) | 5 473 (67) | 5 530 (65) |

| HbS/β0 | 251 (2) | 68 (3) | 203 (2) | 212 (2) |

| HbSC | 2 602 (25) | 625 (24) | 1 954 (24) | 2 105 (25) |

| HbS β+ | 669 (6) | 146 (5) | 506 (6) | 550 (6) |

| Other type | 108 (1) | 23 (1) | 92 (1) | 84 (1) |

This analysis provides a strong foundation for understanding the potential of this data resource for the community. It includes extensive clinical data on individuals that can be followed over time. Using the knowledge about the characteristics of this population, this information can be compared with other research efforts. To our knowledge, this is the largest SCD registry in the United States, as defined by the number of patients and the longitudinal history captured by the program. But additional work is necessary. Ongoing efforts within the Data Hub aim to characterize and standardize data submission practices, improve documentation fidelity, and develop strategies to account for these differences in future research.

SCD comorbidities

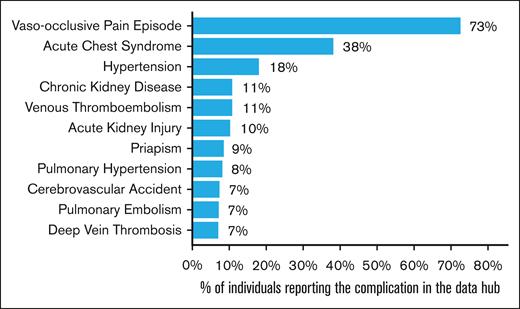

The ASH RC SCD Data Hub Program is working with clinical informaticists and hematologists to inform and prioritize the creation of clinical core data elements and metrics of interest specific to SCD clinical care and research. Extensive work within the Data Hub is underway to develop a database of computable clinical phenotypes, which consists of curated EHR code sets that have high specificity and validity for specific health metrics. Code sets for clinical concepts, such as SCD-associated comorbidities, are constructed using ICD-10, SNOMED-CT, LOINC, RxNorm, and other EHR-based code standards. Although many comorbidities and sequelae of SCD are of interest both clinically and in research, in this report we focus on key comorbidities for which there are ASH RC clinician leader-defined code sets. Specifically, this analysis included acute chest syndrome, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular accidents, deep vein thrombosis, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, priapism (among males), vaso-occlusive pain episodes, and venous thromboembolism.

Figure 6 outlines each of the comorbidities and the proportion of patients with at least 1 record of that comorbidity at any time during their period of active Data Hub follow-up (up to 10 years) between 2015 and 2024. The most reported comorbidity was vaso-occlusive pain episode, with 73% of individuals having at least 1 episode recorded, followed by acute chest syndrome, with 38% of individuals having at least 1 episode recorded during the follow-up period. Some of the comorbidities included are chronic, whereas others are acute, and individuals may experience multiple episodes within the follow-up period. In this report, comorbidities are counted only once per individual. Some counts may reflect comorbidities that occurred or started before the participant’s entry into the Data Hub but were entered in the EHR at some point during the period of their Data Hub follow-up. Future work will look to differentiate comorbidities prevalent at the time of entry into the Data Hub and define discrete episodes for acute comorbidities, which would allow for further investigations into the cross-sectional prevalence, frequency, and recurrence rates of these comorbidities.

Percentage of individuals with at least 1 record of a reported comorbidity.

Leveraging the infrastructure to broaden our impact

The Network is evolving into a holistic and comprehensive platform to accelerate research in SCD. Its scope now extends well beyond traditional pharmaceutical trials, embracing a wide array of research activities, including observational studies, investigator-initiated projects, and prospective evidence collection. By leveraging the SCD Data Hub, the Network harnesses real-world data to generate actionable real-world evidence.

This evolution underscores the critical importance of collaborative research in addressing the changing landscape of SCD. Since its establishment in 2017, the Network has convened a multistakeholder network to systematically address critical gaps in the SCD research agenda.

The Network’s collaborative framework also provides access to a large and diverse patient population, enabling robust trial enrollment, the generation of real-world evidence, and a deeper understanding of the needs of people living with SCD.

The Sickle Cell Disease Research Network stands at the forefront of transformative change. By uniting patients, researchers, and sponsors across a spectrum of innovative initiatives and leveraging a nationally representative data registry, it is uniquely positioned to break through persistent barriers to care, foster trust within the community, and dramatically enhance both the efficiency of clinical trials and the quality of life for individuals living with SCD.

The ASH RC SCD Research Network and its integrated Data Hub mark a significant step forward in enabling collaborative research in SCD. By streamlining data aggregation, supporting multisite studies, and integrating patient voices, the Network enhances study efficiency and relevance. It is well positioned to accelerate therapeutic development, support evidence-based care, and reduce disparities in outcomes. Ongoing collaboration and investment will be essential to sustain this progress.

Authorship

Contribution: F.E.R., B.A., A.K., B.S.P., C.D., and C.S.A. wrote the manuscript; and A.F. and K.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.A. is a consultant for Accordant, Afimmune, Agios, Bayer, Beam Therapeutics, bluebird bio, Chiesi, Editas, Fulcrum, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Guidepoint, Hema Biologics, Hemanext, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Protagonist, Roche, Sanofi, and Vertex; and receives research funding from Afimmune, Agios, American Society of Hematology, Centers for Disease Control, Connecticut Department of Public Health, Hemanext, Health Resources and Services Administration, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Charles S. Abrams, University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104; email: abrams@upenn.edu.