TO THE EDITOR:

Asparaginase is an essential component of the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and has demonstrated improved outcomes with sustained therapy and an increased risk for relapse and death with early asparaginase discontinuation.1-4 Pegylated asparaginases are derived from Escherichia coli with polyethylene glycol attached to prolong drug activity and reduce immunogenicity. Despite existing literature on the pharmacokinetics (PK), therapeutic drug monitoring (serum asparaginase activity [SAA] levels), and toxicity of pegaspargase in children with ALL, limited published data exist for infants younger than 1 year of age with ALL. Infants with ALL comprise a high-risk population with a unique vulnerability to treatment-related toxicity,5-12 partially attributed to the distinct and rapidly developing physiology of organs involved in drug metabolism and excretion and a maturing immune system. Because of the excessive toxicity noted with an induction approach that used the conventional 2500 IU/m2 dosing of pegaspargase for infants with ALL in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) trial AALL0631,13 the AALL15P1 trial implemented age-based pegaspargase dosing and included an embedded optional study to collect data on the SAA levels obtained as part of routine clinical care.14

AALL15P1 was a single-arm study conducted between 2017-2019 that evaluated the safety and tolerability of azacitidine as epigenetic priming before postinduction chemotherapy cycles for infants with newly diagnosed KMT2A-rearranged ALL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02828358).14 Three scheduled doses of pegaspargase were administered, namely 1 each during induction, interim maintenance (IM), and delayed intensification (DI). Pegaspargase was dosed according to age as follows: for induction age <7 days, dosed 1250 IU/m2; age ≥7 days to <6 months, dosed at 1750 IU/m2; age ≥6 to <12 months, dosed at 2000 IU/m2; postinduction therapy age <6 months, dosed at 1650 IU/m2; age ≥6 to <12 months, dosed at 1875 IU/m2; age ≥12 months, dosed at 2500 IU/m2. The collection of blood for SAA measurement was optional but recommended on day 7 following pegaspargase as part of routine clinical care, and results of this testing was collected for patients who provided consent. Data on asparaginase-associated adverse events (Asp-AEs; Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 grade ≥3 unless indicated) were collected for all patients during every cycle and included allergic reactions, anaphylaxis, hyperbilirubinemia, hepatic failure, hypertriglyceridemia, typhlitis, pancreatitis, febrile neutropenia, sepsis, catheter-related infection, site-specific infection (including skin, soft tissue, hepatic, meningitis and lung), multiorgan failure, thrombosis, stroke (all grades), transient ischemic attack (all grades), seizure (all grades), and encephalopathy (including cognitive disturbance, ataxia, memory impairment, and somnolence).

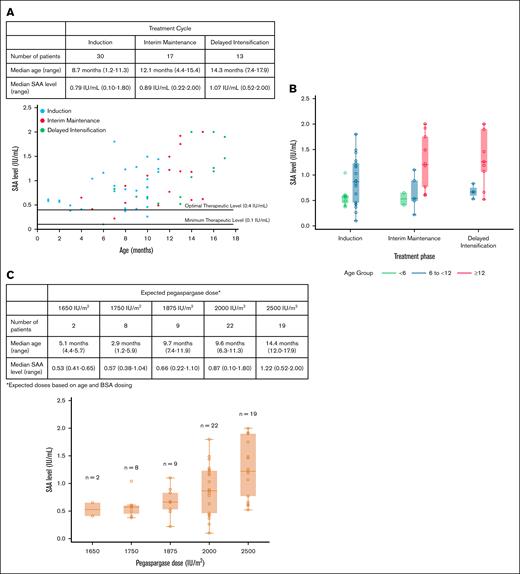

Overall, 78 patients were enrolled and 34 patients provided 60 samples for the measurement of SAA levels; 30 were measured during induction, 17 during IM, and 13 during DI (supplemental Figure 1). The median age at the time of pegaspargase administration was 10 months (range, 1-17) with 10, 31, and 19 measurements obtained from patients aged <6 months, ≥6 to <12 months, and ≥12 months, respectively. There were no significant demographic differences between patients with at least 1 available SAA level measurement and those without (supplemental Table 1). In all patients, SAA was above the minimum therapeutic level (≥0.1 IU/mL) for each measurement, and most patients (n = 55; 92%) achieved a level of ≥0.4 IU/mL, which is predicted to maintain a therapeutic level for at least 14 days after dosing15-17 (Figure 1A). The SAA levels increased with age with median levels of 0.57 IU/mL for those aged <6 months (n = 10), 0.82 IU/mL for those aged ≥6 to <12 months (n = 31), and 1.22 IU/mL for those aged ≥12 months (n = 19; P<.001 using random intercept modeling to account for within-person correlation; supplemental Figure 2). This association persisted after controlling for cycle (P = .004; Figure 1B). The increase in SAA levels with age was a dose-related effect with higher expected pegaspargase dosing (Figure 1C).

SAA levels by treatment phase, age, and pegaspargase dose. Dot plot (A) and box plot (B) of SAA levels by age and treatment phase. (C) SAA levels by expected pegaspargase dose.

SAA levels by treatment phase, age, and pegaspargase dose. Dot plot (A) and box plot (B) of SAA levels by age and treatment phase. (C) SAA levels by expected pegaspargase dose.

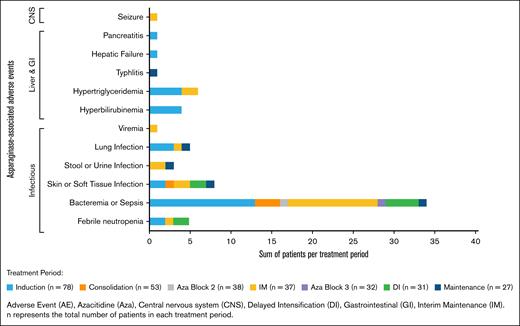

The AALL15P1 regimen was well tolerated with no treatment-related mortality. The Asp-AEs for enrolled patients are summarized by cycle and organ class (Figure 2). There were 83 Asp-AEs reported within 39 unique patients with the highest proportion occurring during IM (n = 18/37 with ≥1 Asp-AE; 49%), followed by induction (n = 24/78; 31%) and then DI (n = 8/31; 26%). Infectious toxicities were the most frequently reported Asp-AEs (n = 69/83; 83%). Given that patients were receiving other myelosuppressive agents simultaneously, isolating the contribution of pegaspargase is challenging. Only 1 patient experienced grade ≥3 pancreatitis, and there were no reports of hypersensitivity reactions, thrombosis, stroke, or encephalopathy. Detailed Asp-AEs by patient and phase of treatment are listed in supplemental Table 2.

Asp-AEs by treatment period. Incidence (patients with >1 event) of Asp-AE by organ system and treatment period.

Asp-AEs by treatment period. Incidence (patients with >1 event) of Asp-AE by organ system and treatment period.

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies that evaluated infant-specific asparaginase dosing, PK, and the only study to our knowledge that has captured asparaginase-associated toxicity data in this unique population. The 7-day SAA levels were all above the minimum therapeutic level and most were above the optimal therapeutic level, suggesting that, despite age-based dose reductions, infants achieve adequate asparagine depletion. The median SAA level increased with age and corresponding dose, indicating that our current dosing strategy can be further refined with formal PK modeling to ensure more comparable exposure in infants up to 1 year of age. Our results align with a recent retrospective analysis of 388 SAA levels from 68 infants performed by Brigitha et al.18 Simulations based on a final population PK model recommended a fixed dose of 1500 IU/m2 for infants under 1 year of age to ensure that 97.5% of patients have SAA levels ≥0.1 IU/mL at day 14. Formal PK analyses that combine both data sets to re-estimate the model parameters and validate the findings should be considered in the future to improve the predictability of the PK model and to further define the optimal dosing strategy of pegaspargase in infants <1 year of age.

The AALL15P1 treatment regimen was well tolerated, which is particularly important given the historic challenges with excessive toxicity in infants. Infectious toxicity was common although not excessive, and there were no treatment-related deaths. Notably, there were no SAA levels indicative of silent inactivation, and no patients experienced hypersensitivity, highlighting that the asparaginase/immune response relationship may differ in infants. Overall, the incidence of asparaginase-associated toxicities in this infant population is lower than that reported in older children and adolescents19,20 with no reported thrombosis, stroke, or encephalopathy and only 1 episode of grade 3 pancreatitis.

A strength of this study is the use of standardized treatment, including pegaspargase, thereby enabling comprehensive evaluation of the SAA levels and toxicity. Limitations include small patient numbers because of the rarity of infant ALL, reporting of standard-of-care SAA testing by COG sites rather than centralized testing, and the evaluation of a single SAA sample following each pegaspargase dose. In addition, our study was not designed to examine whether there is a relationship between asparaginase exposure and outcome and so this warrants assessment in future studies. Since completion of this trial, calaspargase pegol-mknl received US Food and Drug Administration approval and has replaced pegaspargase as the first-line pegylated asparaginase product in the United States for patients aged 1 month to 21 years old, with a recommended dose of 2500 IU/m2 regardless of age.21 However, there are no data on the safety of calaspargase pegol-mknl in infants given that patients under 12 months old were not included in the trials that led to its approval.22,23 The next generation of COG infant ALL trials (NCT06317662 and NCT05761171) incorporate centralized PK testing (SAA levels) at more frequent timepoints and collect asparaginase-associated toxicities to evaluate a calaspargase pegol-mknl dosing strategy in this vulnerable population. Because the only difference between calaspargase pegol-mknl and pegaspargase is the chemical linker that leads to a longer half-life in the former, the rationale for similar age-based dosing is strongly supported by this study, which demonstrates that age-based pegaspargase dosing is safe and achieves adequate asparagine depletion in infants with ALL.

The AALL15P1 trial received institutional review board approval through the Children's Oncology Group National Cancer Institute Pediatric Central Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U10 CA180886 (National Clinical Trials Network Operations Center grant) and U10 CA180899 (Children's Oncology Group Statistics and Data Center grant), the St. Baldrick's Foundation, and Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb. L.G. is the Ergen Endowed Chair in Pediatric Oncology at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. E.R. is a KiDS of New York University (NYU) Foundation Professor at NYU Langone Health. M.L.L. is the Aldarra Foundation Endowed Chair, Bill and June Boeing, Founders, Pediatric Cancer Research at Seattle Children’s Hospital. S.P.H. is the Jeffrey E. Perelman Distinguished Chair in Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. R.S.K. is supported by a Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC APP2033152).

Contribution: K.E.F., R.S.K., and E.G. contributed to the conception and design of the study; K.E.F., J.A.K., E.H., J.L.-B., R.S.K., and E.G. assembled and analyzed the data; and K.E.F. wrote the manuscript with support, editing, and final approval from J.A.K., E.H., J.L.-B., R.S.K., E.G., M.D., A.A., L.G., E.R., S.P.H., M.L.L., D.T.T., P.B., and E.H.B.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.T.T. reports research funding from Beam Therapeutics; and serving on advisory boards (unpaid) for Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Jazz, Servier, Sobi, and J&J Innovation. S.P.H. reports owning common stock in Amgen; and honoraria from Amgen, Jazz, and Servier. L.G. reports owning common stock in Amgen and Sanofi Paris. M.L.L. reports serving on advisory boards for Jazz. P.B. reports being employed by and owning common stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kelly E. Faulk, Department of Pediatrics, Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders, Children's Hospital Colorado, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, 13123 E 16th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045; email: kelly.faulk@childrenscolorado.org.

References

Author notes

A portion of this research was presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 6 May 2022, Pittsburgh, PA, and the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, 1 October 2022, Barcelona, Spain.

Deidentified data from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) trial AALL15P1 are available on request to the trial committee. Request for access to the COG protocol research data should be sent to: datarequest@childrensoncologygroup.org.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.