Key Points

Clinical diagnostic DNA sequencing can be used to identify resistance to immunotherapies, allowing for effective treatment management.

Visual Abstract

Here, we present the case for next-generation sequencing of samples from patients with multiple myeloma (MM), not only identify high-risk markers but also mutations and deletions relating to immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD), and more importantly to guide the sequencing of immunotherapy regimens in response to intrinsic antigen escape as a means of treatment resistance and relapse. This is a single-center study of CD138+ selected (n = 134) bone marrow aspirate samples from patients with smoldering MM (n = 11) and MM (newly diagnosed, n = 38; relapsed, n = 79). Samples were sequenced using a targeted panel in a clinical diagnostics laboratory. Data were analyzed for high-risk markers, treatment-related resistance mechanisms, and precision medicine targets to guide the future treatment of patients in the clinic. High-risk markers, including t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), gain or amplification 1q, deletion of CDKN2C, and deletion or mutation of TP53, were identified in 15% samples from patients with newly diagnosed. At relapse, alterations in the cereblon degradation pathway were found in 24.3% of IMiD-treated patients. Deletions of 4p (CD38) were also enriched in patients who received anti-CD38 treatment (P = .03), which were mostly monoallelic. Deletions and mutations were detected in TNFRSF17-encoding B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in patients treated with anti-BCMA regimens, and the information was used to change the treatment of the patients. Targeted sequencing of diagnostic samples of patients with MM can be used for risk stratification and to monitor and adjust treatments as resistance mechanisms evolve.

Introduction

Despite the mass adoption of next-generation sequencing in the research arena, molecular diagnostics for the risk stratification of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) have languished in the area of cytogenetics and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Many centers do not see the need for improved diagnostics given that most high-risk genomic markers can be identified using traditional techniques, such as FISH, where IGH translocations, gain 1q, and del17p have been the staple for several decades.1 However, here, we present the case for next-generation sequencing of samples from patients with MM, to not only identify high-risk markers but also mutations and deletions relating to immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD) and, more importantly, to guide the sequencing of immunotherapy regimens in response to intrinsic antigen escape as a means of treatment resistance and relapse.

High-risk genomic markers now include the IGH translocations t(4;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20), gain or amplification of 1q21, and deletion of 1p32 or 17p13.2 Crucially, we know the tumor suppressor genes of interest in the deleted cytobands, namely CDKN2C (1p32) and TP53 (17p13),3-5 and that mutations in these genes result in loss of function and are equally as important as deletions.6-8

In addition to high-risk genomic markers, there are a plethora of somatic abnormalities acquired after treatment that are linked to resistance mechanisms. IMiD and proteasome inhibitors have been used to treat patients with MM for many years, and resistance pathways have been identified. IMiDs work by binding to cereblon, resulting in binding to the key MM transcription factors, Ikaros and Aiolos, leading to their ubiquitination and targeting to the proteasome for degradation.9 Mutations and/or deletions of several genes encoding members of this pathway have been associated with resistance to IMiDs, including CRBN, DDB1, CUL4, NEDD3, the COP9 signalosome complex genes located on 2q, and IKZF1 and IKZF3 encoding Ikaros and Aiolos, respectively.10-13 Other genomic markers were also identified in IMiD-treated patients at relapse, including mutations in MAML2, DUOX2, and EZH2 which were at higher frequencies compared to patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM).14

As treatments have changed, resistance mechanisms also change. Now that patients receive immunotherapies targeting cell surface receptors, antigen escape has become a common mechanism of resistance. CD38, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 17 (TNFRSF17; also known as B-cell maturation antigen [BCMA]), and G-protein–coupled receptor class C group 5 member D (GPRC5D) are the most widely used immunotherapy targets, and deletion or mutation of the genes encoding them has been reported in up to 25% of relapsed patients.15-19 Given the variety of immunotherapy options available, it is important to determine whether resistance to treatment is due to tumor intrinsic (eg, antigen escape) or extrinsic mechanisms (eg, T-cell exhaustion) to enable effective treatment decisions.

Therefore, molecular diagnostics in MM must include an assay to detect translocations, copy number abnormalities (CNA), and single-nucleotide variants (mutations) to identify high-risk markers and mechanisms of treatment resistance. This will enable the clinic to more effectively determine the next treatment option available to the patient. We have previously validated a next-generation sequencing–targeted panel assay that was shown to detect each of these abnormalities with high sensitivity and specificity.20 Here, we present the implementation of this panel in a molecular diagnostic setting and highlight its use in the workup of patients with MM, particularly in relation to resistance to immunotherapies.

Material and methods

Patient samples

Patients with MM and related plasma cell dyscrasias between December 2022 and July 2024 at the Indiana University Health hospitals were assessed for genomic abnormalities by a clinical next-generation sequencing panel.20 Patients were enrolled on the Indiana Myeloma Registry, an institutional review board–approved prospective, noninterventional study collecting comprehensive clinical, genomic, demographic, social, environmental, and quality of life data from patients with plasma cell dyscrasias (Table 1). All patients enrolled in the Indiana Myeloma Registry gave informed consent for sample use and data collection.

Patient samples and purity

| Disease . | Stage . | n . | Abnormal PC purity, mean (range), % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMM | ND | 7 | 58 (29-82) |

| SMM | Treated | 4 | 50 (20-82) |

| MM | ND | 38 | 66 (14-95) |

| MM | Follow-up | 5 | 24 (19-32) |

| MM | Relapse | 79 | 60 (12-94) |

| AL amyloid | ND | 1 | 19 |

| Disease . | Stage . | n . | Abnormal PC purity, mean (range), % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMM | ND | 7 | 58 (29-82) |

| SMM | Treated | 4 | 50 (20-82) |

| MM | ND | 38 | 66 (14-95) |

| MM | Follow-up | 5 | 24 (19-32) |

| MM | Relapse | 79 | 60 (12-94) |

| AL amyloid | ND | 1 | 19 |

AL, amyloid light chain; ND, newly diagnosed; PC, plasma cell.

Sample processing

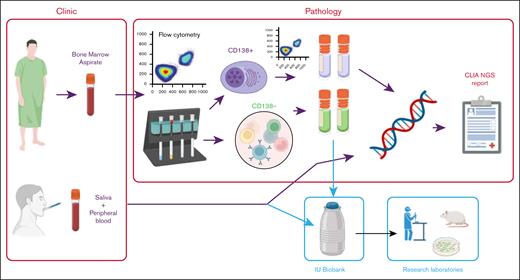

We implemented a workflow to introduce targeted sequencing of CD138+ cells from patients with plasma cell disorders to improve molecular diagnostics (Figure 1; supplemental Methods). Bone marrow aspirates and saliva samples were acquired from patients. The saliva samples were sent directly to the Diagnostic Genomics laboratory for extraction of germ line DNA. In total, 168 bone marrow aspirates were sent to the Hematopathology laboratory where they were assessed for plasma cell involvement by flow cytometry and sorted using anti-CD138 magnetic beads. The CD138+ fraction was reassessed for purity by flow cytometry and number of cells. At this point, 34 samples (20.2%) failed quality control due to insufficient cells. The remaining 134 samples underwent library preparation and hybridization to the Myeloma Genome Project targeted sequencing panel (version 22), followed by paired-end sequencing (Illumina). Data were analyzed, as previously described, somatic variants were visually checked in VarSeq (Golden Helix) and the Integrated Genome Viewer, and a clinical report was generated. The report was periodically discussed in the Multiple Myeloma Tumor Board meeting consisting of clinicians, scientists, pathologists, and imaging specialists.

Overview of process. Bone marrow aspirates taken in the clinic are sent to Hematopathology laboratory to determine abnormal plasma cell count by flow cytometry. Samples underwent CD138+ magnetic cell sorting, followed by purity assessment by flow cytometry. DNA was extracted from up to 0.5 million CD138+ cells. DNA from both CD138+ cells and DNA from saliva or peripheral blood from the same patient underwent library preparation, hybridization, and sequencing. Excess CD138+ and CD138− cells were viably frozen for research purposes. Targeted sequencing data were analyzed for somatic abnormalities and discussed in a molecular tumor board. CLIA NGS, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Next Generation Sequencing; IU, Indiana University.

Overview of process. Bone marrow aspirates taken in the clinic are sent to Hematopathology laboratory to determine abnormal plasma cell count by flow cytometry. Samples underwent CD138+ magnetic cell sorting, followed by purity assessment by flow cytometry. DNA was extracted from up to 0.5 million CD138+ cells. DNA from both CD138+ cells and DNA from saliva or peripheral blood from the same patient underwent library preparation, hybridization, and sequencing. Excess CD138+ and CD138− cells were viably frozen for research purposes. Targeted sequencing data were analyzed for somatic abnormalities and discussed in a molecular tumor board. CLIA NGS, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Next Generation Sequencing; IU, Indiana University.

Results

Impact of sample purity on detection of abnormalities

As part of the diagnostic workflow, post-CD138 selected samples were assessed for abnormal plasma cell purity by flow cytometry. This allowed us to determine the impact of low CD138 purity on the detection of somatic abnormalities, including IGH locus translocations, mutations, and CNA. Samples were assigned to 20 percentile bins based on their post-CD138 selection purity. Samples were annotated for disease and stage, and there was no significant effect of these variables on sample purity (Figure 2A).

Effect of sample CD138 cell purity on detection of somatic abnormalities. (A) Postselection sample purity annotated for disease stage. (B) Detection of IGH translocations in samples of varying purities. (C) Detection of mutations in samples of varying purities. (D) Detection of CNA in samples of varying purities. AL, amyloid light chain; IgH, immunoglobulin H.

Effect of sample CD138 cell purity on detection of somatic abnormalities. (A) Postselection sample purity annotated for disease stage. (B) Detection of IGH translocations in samples of varying purities. (C) Detection of mutations in samples of varying purities. (D) Detection of CNA in samples of varying purities. AL, amyloid light chain; IgH, immunoglobulin H.

We examined samples in each 20-percentile bin for the presence of IGH translocations, mutations, and CNA. IGH translocations should be present in 40% to 50% of samples from patients with MM.21 In the higher purity bins (41%-100% CD138+ cells), the detection rate of IGH translocations in the samples was 43% to 56% (Figure 2B), which is within the expected range. However, for lower purity samples (0%-40% CD138+ cells), the detection of IGH translocations dropped to 18% to 28% of the samples, potentially indicating that some samples were false negatives.

Samples with lower CD138+ cell purity also detected fewer mutations per sample (Figure 2C). In these low-purity samples, it is likely that only clonal mutations were detected, whereas in the high-purity samples, both clonal and subclonal mutations were detected. In 9 samples, no genomic abnormality was detected, all of which had a CD138+ purity <40% (median, 27%), which highlights the need for good-quality samples.

We used an unbiased approach to determine whether copy number detection was also affected by sample purity. iChorCNA was used to generate genome-wide copy number from the targeted panel data, and the presence of any copy number change was noted. Once again, any CNA was identified in 80% to 95% of samples with >40% CD138+ cells compared with 28% to 33% of samples with <40% CD138+ cells. Interestingly, for those with high CD138+ cell purity without CNA, there were still IGH translocations or mutations detected, indicating that the tumor cells had simple genomes without CNA. However, additional drivers may have been missed due to the panel design, including complex structural variants, such as chromothripsis or chromoplexy. The lack of CNA was reflected by iChorCNA-inferred tumor fraction estimates, which were 0 for many samples, when in fact by flow cytometry there were >40% CD138+ cells. This difference reflects the absence of CNA in these samples rather than the actual tumor purity (supplemental Figure 1).

Together, these data indicate that even at low sample purity, some genomic information could be determined from clinical samples, but having a CD138+ population >40% of total cells greatly improved the detection of translocations, mutations, and CNA. Performing CD138 cell selection is essential, and knowing the CD138 purity of the sample after cell selection enables better interpretation of results.

Identification of clinically relevant somatic abnormalities

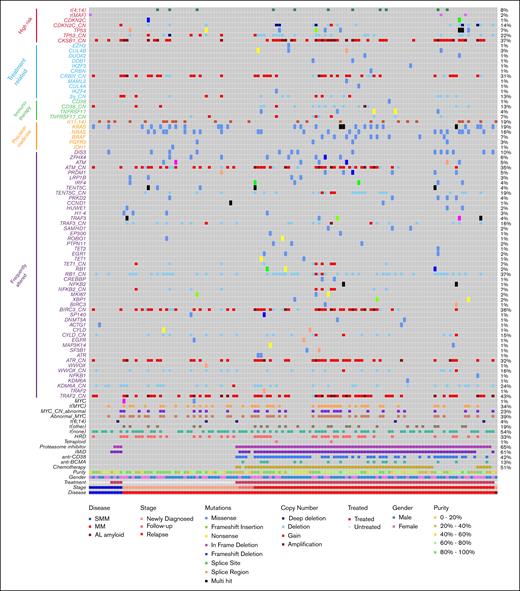

Using data from the 134 processed samples, we identified key genomic abnormalities of clinical interest, including high-risk markers, treatment- or immunotherapy-related markers, markers relevant to precision medicine, and other frequently altered genes (Figure 3; supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

Genomic annotation of samples with clinical targeted sequencing (n = 134). Genes and the copy number states of tumor suppressor genes and prognostic regions shown (_CN). Purity data taken from flow cytometry of sorted CD138+ samples. AL, amyloid light chain; t(none), no immunoglobulin translocation detected.

Genomic annotation of samples with clinical targeted sequencing (n = 134). Genes and the copy number states of tumor suppressor genes and prognostic regions shown (_CN). Purity data taken from flow cytometry of sorted CD138+ samples. AL, amyloid light chain; t(none), no immunoglobulin translocation detected.

High-risk markers

According to the International Myeloma Society-International Myeloma Working Group 2024 consensus definition of high-risk myeloma,22 genomic markers to be assessed include t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), monoallelic or biallelic deletion of CDKN2C (1p32), gain or amplification of 1q (CKS1B), and deletion or mutation of TP53. All these markers can be identified in the Myeloma Genome Project (MGP)-targeted sequencing panel (Figure 3).

The common IGH translocation partners were detected (supplemental Figure 4), including those that are high risk and several infrequent and novel partners. High-risk translocations were detected in 7.9% of patients with NDMM and 8.1% of relapsed patients. In this data set, 7% of samples had a mutation in TP53, which increased in frequency with disease progression (0% smoldering MM [SMM] vs 5.2% NDMM vs 11.4% relapsed/refractory MM [RRMM]) as did deletion of TP53 (0% SMM vs 10.5% NDMM vs 26.6% RRMM), although in this small data set, neither was significantly increased. In the NDMM samples, 3 of the 4 samples with TP53 abnormalities were biallelic, 1 of which was biallelic deletion and the other 2 were mutation plus deletion. In relapsed samples, deletion of TP53 was more prevalent than mutation (26.6% vs 8.9%) and 1 sample had only mutation. Overall, the incidence of biallelic or double-hit TP53 was 0%, 7.9%, and 7.6% at SMM, NDMM, and RRMM, respectively. For CDKN2C, the frequency also increased with disease stage (0% SMM vs 7.9% NDMM vs 17.7% RRMM), but it was not statistically significant. There was a significant increase in the gain or amplification of 1q (CKS1B locus) which increased from NDMM to RRMM (27% SMM vs 21% NDMM vs 49.4% RRMM; P < .001 for NDMM vs RRMM). According to International Myeloma Society-International Myeloma Working Group 2024 high-risk criteria, 6 of 38 samples from patients with NDMM (15.8%) were classified as high risk by genomic abnormalities.

Markers associated with therapy resistance

In addition to high-risk genomic markers, we detected mutation or deletion of previously reported IMiD resistance genes, including members of the cereblon degradation pathway (CRBN, CUL4A, CUL4B, COP9 loci on 2q, and DDB1) which normally degrade Ikaros family members (Figure 3).9,12,23 Mutations or copy number loss was only found in patients previously treated with IMiD, with the exception of deletion of 2q (COP9 loci) and CRBN on 3p which were present in 2 samples at diagnosis. Although we did not identify any mutations in IKZF1 or IKZF3, we did see 1 sample with mutated IKZF4 (encoding Eos). In total, 22.8% of IMiD-treated patients demonstrated abnormalities in the cereblon degradation pathway. Furthermore, mutations in EZH2, DUOX2, and MAML2 at low frequencies in relapsed patient samples were identified, which have previously been found to be enriched in relapsed patient samples.14

Markers associated with precision medicine

We also identified alterations relating to precision medicine. The most obvious candidate is the t(11;14), which is associated with a better overall response rate to venetoclax than other myeloma subgroups24 and was detected in 19% of the samples. Other potential alterations relating to precision genomics could include activating mutations in KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF, which can be targeted directly by inhibitors25,26 or indirectly through the MAPK pathway (34% of patients).27 Furthermore, inhibitors targeting specific Ras variants are now being trialed in solid tumors,28,29 and being able to annotate patients for these variants now may help to identify them for future clinical trials. Although much less frequent than Ras mutations, IDH1 mutations were identified in 1 sample (0.7%) and are targetable in other diseases.30 Moreover, an IGH translocation to LYN (encoding a Src family kinase) would result in overexpression, which could be inhibited by US Food and Drug Administration–approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Identification of deletion or mutation of immunotherapy targets to inform treatment decisions

The MGP panel (version 22) includes genes encoding immunotherapy targets, including TNFRSF17 (BCMA), CD38, GPRC5D, SLAMF7, and FCRL5 (Fc receptor homolog 5). Therefore, the incidence of deletion or loss of these target genes in patients who had been treated with the relevant therapies was evaluated.

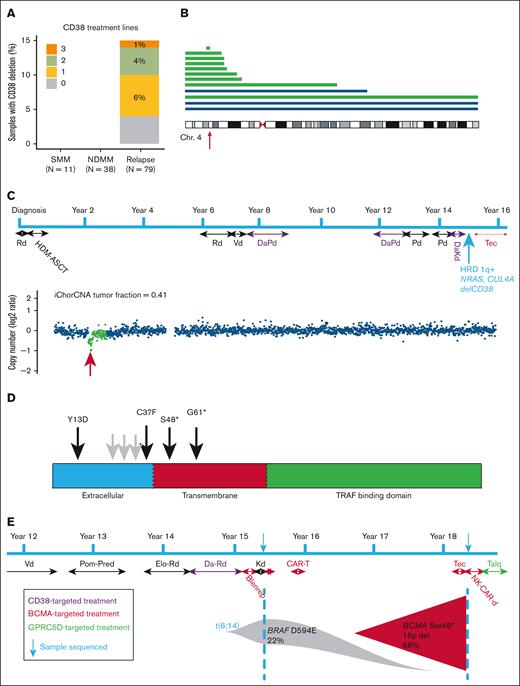

Deletion of chromosome 4p in anti-CD38–relapsed samples

Apart from gain/amp1q, deletion of CD38 was the only genomic event that significantly increased from NDMM to RRMM (Figure 4A; supplemental Tables 1 and 2). At SMM and NDMM stages, no deletions of CD38 were detected, which increased to 15.2% at relapse (0/38 vs 12/79; P = .02). Three patients with deletion of CD38 did not receive anti-CD38 treatment, 2 of them had deletion of entire chromosome 4, likely unrelated to CD38. After removing these 3 samples from the analysis, there was still a significant increase in deletion of CD38 at relapse (P = .03). An increased incidence of 4p deletion had not been identified in a previous data set of patients relapsing after IMiD treatment (without anti-CD38), indicating that deletion is probably due to anti-CD38 treatment.14

Clinical targeted sequencing identifies mutation or deletion of immunotherapy targets. (A) Percent of samples at each disease stage with deletion CD38 and number of prior lines of anti-CD38 received. (B) Deletions of chromosome 4 in relapsed patients with prior lines of anti-CD38 treatment. Each line represents a patient and the extent of the deletion. The blue lines depict deletions in patients who were anti-CD38 naive, whereas the green lines were patients who received anti-CD38. The red arrow indicates the position of CD38. (C) Patient treatment timeline for a patient identified with deletion of CD38 after anti-CD38 treatment. The blue arrow indicates sample time point with key genomic features. iChor copy number profile of chromosome 4 (lower). Location of CD38 indicated by the red arrow. (D) Mutations in TNFRSF17 (BCMA) detected after anti-BCMA treatment. The black arrows indicate mutations detected in this study, whereas the gray arrows indicate previously identified mutations. (E) Patient treatment timeline revealing sequencing date from 2-sample time points before and after anti-BCMA treatments. Blenrep, belantamab mafodotin-blmf; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; Chr. 4, chromosome 4; DaKd, daratumumab carfilzomib dexamethasone; DaPd, daratumumab pomalidomide dexamethasone; DaRd, daratumumab lenalidomide dexamethasone; Elo-Rd, elotuzumab lenalidomide dexamethasone; HDM-ASCT, high-dose melphalan autologous stem cell transplant; HRD, hyperdiploidy; Kd, carfilzomib dexamethasone; NK-CAR-d, natural killer cell chimeric antigen receptor dexamethasone; Pd, pomalidomide dexamethasone; Pom-Pred, pomalidomide prednisone; Rd, lenalidomide dexamethasone; Talq, talquetamab; Tec, teclistimab; Vd, bortezomib dexamethasone.

Clinical targeted sequencing identifies mutation or deletion of immunotherapy targets. (A) Percent of samples at each disease stage with deletion CD38 and number of prior lines of anti-CD38 received. (B) Deletions of chromosome 4 in relapsed patients with prior lines of anti-CD38 treatment. Each line represents a patient and the extent of the deletion. The blue lines depict deletions in patients who were anti-CD38 naive, whereas the green lines were patients who received anti-CD38. The red arrow indicates the position of CD38. (C) Patient treatment timeline for a patient identified with deletion of CD38 after anti-CD38 treatment. The blue arrow indicates sample time point with key genomic features. iChor copy number profile of chromosome 4 (lower). Location of CD38 indicated by the red arrow. (D) Mutations in TNFRSF17 (BCMA) detected after anti-BCMA treatment. The black arrows indicate mutations detected in this study, whereas the gray arrows indicate previously identified mutations. (E) Patient treatment timeline revealing sequencing date from 2-sample time points before and after anti-BCMA treatments. Blenrep, belantamab mafodotin-blmf; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; Chr. 4, chromosome 4; DaKd, daratumumab carfilzomib dexamethasone; DaPd, daratumumab pomalidomide dexamethasone; DaRd, daratumumab lenalidomide dexamethasone; Elo-Rd, elotuzumab lenalidomide dexamethasone; HDM-ASCT, high-dose melphalan autologous stem cell transplant; HRD, hyperdiploidy; Kd, carfilzomib dexamethasone; NK-CAR-d, natural killer cell chimeric antigen receptor dexamethasone; Pd, pomalidomide dexamethasone; Pom-Pred, pomalidomide prednisone; Rd, lenalidomide dexamethasone; Talq, talquetamab; Tec, teclistimab; Vd, bortezomib dexamethasone.

Deletions ranged from loss of the entire chromosome 4 and deletions extending to the pter, to a single focal deletion. Most deletions of CD38 were monoallelic, suggesting that haploinsufficiency may be enough to generate resistance to treatment; this has been found to reduce CD38 cell surface expression.17 The patient with the focal deletion of CD38 had received 3 prior lines of anti-CD38 treatment (Figure 4B). At the time of sampling, the patient was 14 years from diagnosis of myeloma and had received 7 lines of treatment after autologous stem cell transplant. The CD138+ tumor fraction in the samples was 41%, indicating that the focal deletion is likely biallelic in the myeloma clone after taking into account the purity of the sample. In addition to the focal deletion of CD38, this sample was also hyperdiploid with del(TENT5C), gain1q, and mutations in NRAS and CUL4A (IMiD resistance). Although we were not able to confirm loss of CD38 expression at the protein level in this sample, we were able to analyze existing clinical flow cytometry data from another sample which had a larger subclonal deletion of 4p spanning ∼27 Mb. Flow cytometry data from this sample indicated 2 kappa-restricted populations of CD138+ cells which differed in their expression of CD38, indicating that the deletion likely affects expression of the gene (supplemental Figure 5). The diagnostic sample from this patient had not been analyzed by either flow cytometry or sequencing, so we cannot definitively reveal that deletion is a resistance mechanism related to anti-CD38 treatment.

In total, 56 patients received anti-CD38 treatment, indicating that 16% (9/56) of those had deletions of the target. There was no significant increase in the frequency of deletion with prior lines of anti-CD38 treatment (deletion with 1 prior line of anti-CD38, 4/34 [11.8%]; 2 prior lines, 4/16 [25%]; 3 prior lines, 1/6 [16.6%]). Interestingly, 1 patient who had not received anti-CD38 treatment had a somatic mutation of CD38 (S29I, predicted to be on the cytoplasmic tail and therefore not part of the antibody recognition sequence); consequently, not all alterations of target genes are due to therapy resistance.

These data indicate that deletion of CD38 can occur after 1 line of anti-CD38 treatment and is a likely mechanism of treatment resistance which should be monitored; this has also recently been revealed by others.31 In addition, sequential diagnostic sampling of patients will help determine which abnormalities are selected due to resistance mechanisms vs being unrelated passenger mutations.

Deletion and mutation of TNFRSF17 in post–BCMA-treated samples

For TNFRSF17 (BCMA), 16 patients had been previously treated with an anti-BCMA therapy. Of these 16 patients, 4 samples (25%) had mutations in TNFRSF17 (Figure 4C). The mutations were either missense mutations in the extracellular domain (recognized by the therapy) or nonsense mutations in the transmembrane domain (resulting in truncated proteins that would not remain on the cell surface). In addition, there was 1 sample with a somatic mutation (L60S) in TNFRSF17 in an anti-BCMA–naive patient. This mutation was present in the transmembrane domain and may be a passenger, again necessitating the need for sequential sampling from diagnosis to identify true drivers of resistance.

Deletions of TNFRSF17 were present in 2 post–BCMA-treated samples and an additional 3 treatment-naive samples. Both deletions in the post-treatment samples coincided with the nonsense mutations, resulting in biallelic loss of TNFRSF17. One of the missense mutations had a variant allele frequency of 0.74 without copy number change. Given the purity of the sample (estimated at 71%) and the same allelic imbalance in single nucleotide polymorphisms elsewhere on 16p, we assume copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity for the mutated copy of TNFRSF17.

For another patient with biallelic, loss there was an additional biobanked pretreatment sample that was subsequently analyzed (Figure 4D). The first sample was 15 years postdiagnosis, and at that time, the patient had received proteasome inhibitor/IMiD combinations and anti-SLAMF7 and anti-BCMA antibody-drug conjugate but did not respond. No TNFRSF17 mutations or deletions were observed at this time point, but a t(6;14) and BRAF (D594E) mutation were detected. Three years later, after anti-BCMA chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy and anti-BCMA bispecific T-cell engager, the patient relapsed, and a clone with deletion and mutation of TNFRSF17 was found in 66% of tumor cells. The patient was subsequently moved to an anti-GPRC5D treatment and went into remission.

These examples of identifying alterations in immunotherapy targets demonstrate the need for DNA sequencing of patient samples to identify mechanisms of resistance in real time that will inform the next treatment to be used.

Detection of PGV

It was previously noted that ∼8% of patients with MM may harbor pathogenic germ line variants (PGV), particularly in DNA repair pathway genes.32 We used the germ line DNA as a patient-matched control to determine whether any PGV were present in our data set. The MGP panel contains 14 of the 48 genes previously tested in whole-genome sequencing data sets, including those genes with the most frequently detected clinically actionable genes: ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, and CHEK2 (supplemental Table 3).

The panel detected PGV in 6 patient samples (4.5%; Table 2), including nonsense mutations in ATM and FANCM, a missense mutation in FANCA, a splice-site mutation in ATM, and a frameshift in BRCA2. All mutations had a variant allele frequency consistent with a heterozygous mutation, and the patient harboring the frameshift mutation in BRCA2 had also been diagnosed with male breast cancer. The patient with a germ line nonsense mutation in ATM (E1798∗) also had a somatically acquired mutation in ATM (V2731G), which has previously been reported as pathogenic.33 In this patient, the combination of germ line plus somatic mutations could indicate biallelic loss of function in ATM in the tumor, illustrating the need for paired germ line and tumor DNA analysis.

PGV

| Patient . | Gene . | Chr . | Position . | Amino acid change . | VAF . | ClinVar Sig . | Somatic mutation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0661-518 | ATM | 11 | 108267344 | Splice site | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | gain11 |

| 0661-1581 | ATM | 11 | 108312424 | E1978Ter | 0.47 | Pathogenic | V2731G |

| 0661-1580 | BRCA2 | 13 | 32336283 | R645fs | 0.49 | Pathogenic | None |

| 0661-1408 | FANCA | 16 | 89746848 | T1131A | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

| 0661-1082 | FANCM | 14 | 45198718 | R1931Ter | 0.46 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

| 0661-344 | FANCM | 14 | 45198718 | R1931Ter | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

| Patient . | Gene . | Chr . | Position . | Amino acid change . | VAF . | ClinVar Sig . | Somatic mutation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0661-518 | ATM | 11 | 108267344 | Splice site | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | gain11 |

| 0661-1581 | ATM | 11 | 108312424 | E1978Ter | 0.47 | Pathogenic | V2731G |

| 0661-1580 | BRCA2 | 13 | 32336283 | R645fs | 0.49 | Pathogenic | None |

| 0661-1408 | FANCA | 16 | 89746848 | T1131A | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

| 0661-1082 | FANCM | 14 | 45198718 | R1931Ter | 0.46 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

| 0661-344 | FANCM | 14 | 45198718 | R1931Ter | 0.49 | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | None |

Chr, chromosome; VAF, variant allele frequency.

Discussion

Here we have shown that there is a clear advantage of performing genomic DNA sequencing of samples from patients with MM than existing FISH techniques. Although we currently think of molecular diagnostics to risk stratify patients, there is also a need for diagnostic testing to inform the clinic of evolution of tumors in response to treatments.

It is probable that comprehensive clinical molecular diagnostics for MM and other cancers will eventually comprise of whole-genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, and even single-cell sequencing.34 However, at the moment, these technologies are still complicated and time consuming to analyze, resulting in tests that are overly expensive and cannot be reported to the clinic in a timely manner. These assays will become automated over time to make the process more efficient, but even with improvements in data processing, we still need to learn and prioritize what is important to know and report to the clinic vs results that are interesting from a research point of view but make no difference to the treatment of the patient. We have detailed some pros and cons of targeted panels vs exome or genome sequencing in Table 3.

Pros and cons of sequencing modalities

| Variable . | FISH . | Targeted panel sequencing . | Whole-exome sequencing . | Whole-genome sequencing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | +++ | + | ++ | ++++ |

| Depth of coverage | N/A | +++ | ++ | + |

| Analysis time | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Laboratory processing | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Immunoglobulin translocations | Detected | Detected | Not detected | Detected |

| Complex SVs | Not detected | Detected (depends on location) | Detected (depends on location) | Detected |

| Sensitivity | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Mutations | Not detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Copy number | Detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| APOBEC signature | Not detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Bias | ++++ | +++ | ++ | − |

| Variable . | FISH . | Targeted panel sequencing . | Whole-exome sequencing . | Whole-genome sequencing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | +++ | + | ++ | ++++ |

| Depth of coverage | N/A | +++ | ++ | + |

| Analysis time | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Laboratory processing | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Immunoglobulin translocations | Detected | Detected | Not detected | Detected |

| Complex SVs | Not detected | Detected (depends on location) | Detected (depends on location) | Detected |

| Sensitivity | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Mutations | Not detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Copy number | Detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| APOBEC signature | Not detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Bias | ++++ | +++ | ++ | − |

−, none; +, low; ++, medium; +++, high; ++++, very high; N/A, not applicable; SV, structural variant.

A stop gap to solve this problem is the introduction of smaller DNA sequencing panels that are targeted to identify genomic abnormalities that are clinically relevant.20,35,36 Here, we have revealed that such a panel can identify the primary immunoglobulin translocations and hyperdiploidy, including loss of key tumor suppressor genes, CDKN2C and TP53 which can be mutated or deleted, and gain/amplification of 1q, thereby identifying all the current genomic high-risk abnormalities.22 However, if new high-risk abnormalities are determined in multiple data sets, these will have to be added.37-40 Some abnormalities will be difficult to assess with targeted panels such as genome complexity or complex structural variants which are not recurrently found in the same parts of the genome.

We also know from prior research studies that there are genomic abnormalities associated with resistance to treatments, including proteasome inhibitors, IMiD, and immunotherapies.9,12,14,23 Identifying these abnormalities is arguably more important than identifying high-risk markers, as they are markers notifying the clinic which treatment needs to be changed. The most obvious example of this is antigen escape,15,18,19 when the tumor loses the cell surface protein that is targeted by an immunotherapy; if BCMA has been deleted from the tumor genome there is no point in continuing with any anti-BCMA treatment but another protein could be targeted instead (eg, GPRC5D). However, serial samples from patients should be analyzed to determine if clones present at subsequent relapses contain deletions of both BCMA and GPRC5D, or only GPRC5D. If the latter, this gives the clinic an opportunity to restart anti-BCMA therapy, although we currently do not have enough data to know how long subsequent remissions may last, given that a BCMA-deleted cell already exists at undetectable levels.

Our overall success rate of 80% is perhaps a little low, but it can be easily increased. The initial sample requirements were 0.5 million CD138+ cells, which was subsequently reduced to allow the assay to be run on more samples. It should be possible to reduce this further, given the possibility of low-input DNA sample preparation kits. The 80% success rate is a little lower than that recently reported by a multicenter study, in which the success rate for FISH was 85%,41 even after decades of clinical implementation. In that study, a second bone marrow sample was taken from those patients where the first test failed, but only half of those gave a result. We also hope to improve the turnaround time, which is dependent on sample numbers being processed. As the test is more widely adopted, it will reduce processing and sequencing time and costs. Overall, the success rates exemplify the problems with obtaining good-quality clinical samples to identify genomic markers in a heterogeneous disease, such as myeloma. A more recent discovery has been the identification of PGV in patients with MM.32 Because we use patient-matched nontumor DNA (from buccal swab or peripheral blood) to identify true somatic mutations, we can use the data to identify germ line variants. In this data set, we identified 6 patients with PGV, including 1 with a germ line splice-site mutation in ATM where there was also a somatic mutation of ATM in the tumor, suggesting biallelic loss of this key tumor suppressor gene. It is not yet clear what the clinical implications of these PGV are for patients with MM, although a previous study indicated that these patients benefit from high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell therapy.32

In summary, we urge centers to move toward clinical DNA sequencing of tumor samples from patients with MM. We recommend that CD138+ cell selection is performed and that the cell selection efficiency is assessed as it can affect the detection of abnormalities. We recommend that high-risk markers and tumor resistance markers are reported to the clinic and that these are discussed in a tumor board meeting involving the diagnostic team, clinicians, and disease genomic experts where available. The joint information from each individual who understands the assay, the treatment history, and the relevance of the markers can be invaluable for the future treatment of the patient. The resources needed to upgrade a FISH diagnostic laboratory to a modern molecular diagnostic laboratory may include access to standard molecular biology reagents, as well as sequencers, data storage and processing, and bioinformatics officers to process data in a uniform fashion. The skillset may be different between FISH and next-generation sequencing analysis, but both are complex processes and require appropriate training to do them in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cameron Morgan for her contributions to the plasma cell myeloma next-generation sequencing panel as a clinical test at Indiana University Diagnostics Genomic Laboratory.

The Indiana Myeloma Registry is funded, in part, by the Indiana University Precision Health Initiative, Miles for Myeloma, the Harry and Edith Gladstein Chair, and the Omar Barham Fighting Cancer Fund. Computational infrastructure at Indiana University (Indianapolis, Indiana) was funded, in part, by Lilly Endowment Inc through the Indiana University Pervasive Technology Institute. B.A.W. is funded by Blood Cancer United (8049-25), US Department of War (CA230482), the International Myeloma Society, and the Daniel and Lori Efroymson Chair. Additional support was provided by the Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center support grant P30 CA082709.

Authorship

Contribution: P.S., E.L., W.N., and S.M.B. analyzed data; L.W., G.T., C.L., and R.A. performed sample processing and data generation through the diagnostic workflow; F.V., M.C., and M.K.T. supervised the clinical workflow and analyzed data; P.P. and M.S. collated and analyzed clinical data; K.L., R.A., and A.S. provided clinical input and enrolled patients in the study; R.A. provided funds for research biobanking; B.A.W. conceptualized the project, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and agreed to the contents of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.M.B. declares employment and equity in Fountain Life. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brian A. Walker, University of Miami, 1550 NW 10th Ave, PAP-511, Miami, FL 33136; email: brianwalker@miami.edu.

References

Author notes

Raw sequencing data have been submitted to database of Genotypes and Phenotypes under accession number phs003908.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.