Key Points

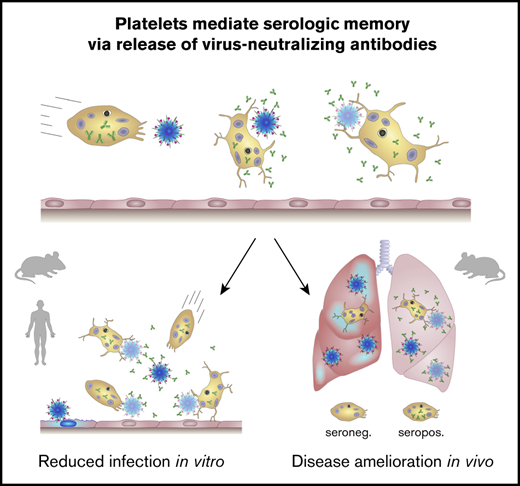

Platelets contain virus-specific IgGs that potently diminish viral infection in vitro and in vivo.

Release of platelet IgG is more efficient at virus neutralization than equal amounts of plasma IgG.

Introduction

Antibody-mediated neutralization of pathogens is a key function of adaptive immunity. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) molecules bind to invading pathogens with high affinity and specificity. Platelets are known to contain IgG in their α-granules1 ; however, the biological significance of this antibody reservoir is unclear. In addition to their primary role in hemostasis, platelets are active and autonomous participants in host immune responses to bacterial and viral infections.2

Platelets express various receptors, such as Toll-like receptors 2 and 7, for direct responses to viruses, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) and influenza A virus (IAV).3-7 Because of their high sensitivity, rapid responsiveness, and sheer number, platelets function as sentinels and as the first line of defense against invading pathogens. Upon virus recognition, platelets contribute to pathogen clearance by engulfing virus particles and modulating leukocyte effector function.5,8,9 Although platelet-derived antimicrobial peptides restrict bacterial infection,10 the impact of platelet-derived IgG is unknown.

Here, we investigated platelet effects on virus neutralization via IgG release and found an unexplored mechanism to potentiate humoral immunity, which might be used for platelet-based drug-delivery therapy.

Methods

In vitro and in vivo neutralization assays with CMV (clinical isolate VR1814) and IAV (strain A/PR/8/34 H1N1) are described in supplemental Methods. RNA extraction, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunofluorescence microscopy, and statistical analysis are described in supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

Platelets have been shown to modulate immune responses to viral infection.11 Therefore, we investigated the effect of platelets on virus neutralization. To address this, we coincubated CMV-infected human endothelial cells with human platelets and quantified viral infection by CMV immediate early expression. We found that a subgroup of platelet donors efficiently reduced CMV infection (Figure 1A), which was associated with donor serostatus for anti-CMV–IgG (Figure 1B-C) and mimicked the effects of plasma (supplemental Figure 1). Similar effects for platelet-derived IgG were obtained under capillary shear stress (supplemental Figure 2), highlighting a possible in vivo relevance of our findings.

Seropositive platelets efficiently neutralize viral infection in vitro via their IgG. (A) Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were infected with CMV (5 hours) and incubated with buffer (control), undiluted plasma, or platelets for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative CMV immediate early (IE) expression (n = 8-14). (B) Blood donors in panel A were stratified according to their anti-CMV IgG serostatus in seronegative (neg.) and seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 7). (C) The relative number of infected HUVECs was quantified by immunofluorescence 72 hours after infection (right panel). Representative images show noninfected HUVECs (Non-inf.) CMV-infected HUVECs incubated with buffer (CMV [control]), or platelets of a seronegative (CMV+PLT neg.) or seropositive (CMV+PLT pos.) donor (left panels). Blue, DAPI; yellow, IE (CMV); red, CD61 (platelets). (D) Surface and intracellular IgG levels of human platelets were determined via flow cytometry (n = 16). (E) Total IgG levels in human citrate-theophyllin-adenosine-dipyridamole (CTAD) plasma and platelet releasate (PLTR) were examined by ELISA (n = 10). (F) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 10). (G) As in panel A, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with ticagrelor (Tica), aspirin (ASA), compstatin (Comp), or P-selectin blocking antibody (P-sel) before incubation with CMV-infected HUVECs (n = 7-13). (H) As in panel A, but CMV-infected HUVECs were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 4-5). (I) As in panel G, but PLTR was optionally treated for 20 minutes with Comp. Alternatively, CMV-infected cells were incubated with IgG-depleted seropositive PLTR (IgG-depl), isolated IgG of seropositive PLTR (IgG only), or seronegative PLTR reconstituted with isolated seropositive IgG (+IgG) (n = 4-5). (J) Total IgG levels in naive murine plasma and PLTR were examined by ELISA (n = 8). (K) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 8). (L) MDCK cells were infected with IAV (2 hours) and incubated with buffer (control) or platelets from anti-IAV IgG seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) mice for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative IAV hemagglutinin (HA) expression (n = 24-26). (M) As in panel L, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with Tica, ASA, Comp, or P-sel before incubation with IAV-infected MDCK cells (n = 12-26). (N) Platelets of Tica- or control-treated mice were stimulated for 15 minutes with IAV or convulxin (CVX), and released IgG was quantified by ELISA (n = 5). (O) As in panel L, but IAV-infected MDCK cells were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donor mice (n = 15-17). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 between indicated groups; #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001, ####P < .0001 vs control. HPRT, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; ns, not significant; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; -, no additional treatment.

Seropositive platelets efficiently neutralize viral infection in vitro via their IgG. (A) Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were infected with CMV (5 hours) and incubated with buffer (control), undiluted plasma, or platelets for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative CMV immediate early (IE) expression (n = 8-14). (B) Blood donors in panel A were stratified according to their anti-CMV IgG serostatus in seronegative (neg.) and seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 7). (C) The relative number of infected HUVECs was quantified by immunofluorescence 72 hours after infection (right panel). Representative images show noninfected HUVECs (Non-inf.) CMV-infected HUVECs incubated with buffer (CMV [control]), or platelets of a seronegative (CMV+PLT neg.) or seropositive (CMV+PLT pos.) donor (left panels). Blue, DAPI; yellow, IE (CMV); red, CD61 (platelets). (D) Surface and intracellular IgG levels of human platelets were determined via flow cytometry (n = 16). (E) Total IgG levels in human citrate-theophyllin-adenosine-dipyridamole (CTAD) plasma and platelet releasate (PLTR) were examined by ELISA (n = 10). (F) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 10). (G) As in panel A, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with ticagrelor (Tica), aspirin (ASA), compstatin (Comp), or P-selectin blocking antibody (P-sel) before incubation with CMV-infected HUVECs (n = 7-13). (H) As in panel A, but CMV-infected HUVECs were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 4-5). (I) As in panel G, but PLTR was optionally treated for 20 minutes with Comp. Alternatively, CMV-infected cells were incubated with IgG-depleted seropositive PLTR (IgG-depl), isolated IgG of seropositive PLTR (IgG only), or seronegative PLTR reconstituted with isolated seropositive IgG (+IgG) (n = 4-5). (J) Total IgG levels in naive murine plasma and PLTR were examined by ELISA (n = 8). (K) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 8). (L) MDCK cells were infected with IAV (2 hours) and incubated with buffer (control) or platelets from anti-IAV IgG seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) mice for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative IAV hemagglutinin (HA) expression (n = 24-26). (M) As in panel L, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with Tica, ASA, Comp, or P-sel before incubation with IAV-infected MDCK cells (n = 12-26). (N) Platelets of Tica- or control-treated mice were stimulated for 15 minutes with IAV or convulxin (CVX), and released IgG was quantified by ELISA (n = 5). (O) As in panel L, but IAV-infected MDCK cells were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donor mice (n = 15-17). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 between indicated groups; #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001, ####P < .0001 vs control. HPRT, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; ns, not significant; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; -, no additional treatment.

In line with previous reports demonstrating that platelet IgG is located within α-granules,1 we found that IgG was mainly stored intracellularly (Figure 1D). IgG levels released by platelets were ∼100-fold to 200-fold lower than those in plasma (Figure 1E-F). This is comparable to previous reports on individual platelets containing ∼20 000 IgG molecules, translating to 1 to 2 µg/mL in whole blood.1,12

Because antiplatelet therapy might be linked to prevalence or severity of infections,13 we determined the effect of platelet inhibition on their antiviral capacity. Inhibition of seropositive platelets with a P2Y12 blocker (ticagrelor) or cyclooxygenase inhibitor (aspirin) did not significantly affect virus neutralization. Similarly, inhibition of the complement system by compstatin and blocking of direct platelet-endothelial cell interactions via P-selectin did not interfere with the antiviral capacity of seropositive platelets (Figure 1G).

To further determine the specificity of IgG and the necessity of cofactors, we investigated the effect of platelet releasate (PLTR) on CMV infection. PLTR from seropositive donors, but not from seronegative donors, reduced CMV viral load in an IgG-dependent manner, because IgG depletion abrogated the effect (Figure 1H-I). Accordingly, seronegative releasate supplemented with IgG from seropositive releasate gained antiviral capacity (Figure 1I).

Release of virus-specific IgG and subsequent formation of immune complexes may trigger virus clearance by platelets themselves (eg, via Fcγ receptor IIA [FcγRIIA] present on human platelets).14 Indeed, human platelets ensnare and kill IgG-opsonized bacteria,15 and platelets of IAV patients have been demonstrated to phagocytose IAV particles.5 Notably, engulfment of viral particles is not solely dependent on FcγRIIA; murine platelets, which are devoid of FcγRIIA,16 also contain virus particles upon IAV infection.9

Analogous to human platelets, IgGs in murine platelets are mostly located intracellularly (supplemental Figure 3), and mice showed similarly low platelet/plasma IgG ratios as humans (Figure 1J-K). Furthermore, anti-IAV–IgG seropositive, but not seronegative, platelets significantly reduced IAV infection of Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells in vitro, whereas comparable plasma levels using a 1:100 or 1:1000 dilution did not (Figure 1L; supplemental Figure 4). Of note, although donor mice differed strongly with regard to IgG levels specific for IAV hemagglutinin (HA), total plasma IgG was equal (supplemental Figure 5A-B), and anti-HA–IgG levels in platelets were ∼200-fold lower than in plasma (supplemental Figure 5C). Again, targeting platelet activation, the complement system, or cell-cell interactions via P-selectin did not affect the antiviral capacity of seropositive platelets (Figure 1M). In line with this, platelets from mice treated with ticagrelor, which almost completely abolished CXCL4 release, were not impaired in terms of their IgG release, and their plasma IgG levels were not affected (Figure 1N; supplemental Figure 6). Further, antiviral capacity was retained in seropositive PLTR (Figure 1O).

Given the fact that IAV and CMV induce platelet degranulation and that platelet α-granules have been shown to store IgG, the lack of effect of ticagrelor or aspirin in the human and murine setting was intriguing. We previously showed that CMV activates only a minority of platelets and depends on adenosine diphosphate feedback for amplification.8 However, our results suggest that platelet IgG release is independent of feedback mechanisms, indicating that the beneficial antiviral capacity of platelets for recurrent infections is independent of antiplatelet therapy. No study has yet investigated the effect of platelets on the susceptibility to recurring infections. However, among critically ill pediatric influenza patients, the risk of an association between 90-day mortality and cyclooxygenase inhibitor use was increased slightly after adjusting for influenza vaccination.17

To demonstrate the in vivo relevance of our findings, we transfused equal amounts of anti-HA–IgG seropositive or seronegative platelets into thrombocytopenic mice18 before challenging them with IAV (Figure 2A-B). Although weight loss was comparable between transfusion groups (supplemental Figure 7A), platelet seropositivity significantly decreased pulmonary viral load (Figure 2C). This was accompanied by overall reduced pulmonary damage, as indicated by lower severity scores for edema formation, alveolar hemorrhage (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 7B), and alveolar exudation (supplemental Figure 7C-D). In accordance with reduced infectious burden of the lung, transfusion of seropositive platelets also curtailed pulmonary platelet infiltration (Figure 2F-G) and dampened antiviral immune responses, as evaluated by expression of interferon response factor 5 or interferon-γ (Figure 2H; supplemental Figure 7E). To understand the importance of platelets as a source of IgG, we further transfused seropositive platelets in diluted seronegative plasma or vice versa and ensured that equivalent levels of anti-HA–IgG were transfused (supplemental Figure 7F). Consistent with our previous findings, weight loss was similar (supplemental Figure 7G), but platelet seropositivity ameliorated viral load and antiviral host responses, whereas transfusion of equivalent plasma anti-HA–IgG was not beneficial (Figure 2I-J; supplemental Figure 7H). This indicates that platelets as a cellular source for IgG are crucial for antiviral effects and could potentially focus IgG at sites of infection, because the enhanced efficacy of platelet-derived IgG over equivalent plasma IgG could be due to site-directed delivery by platelets and, thus, locally increased titers.

Platelets neutralize viral infection in vivo depending on their serostatus. (A) Transfusion setup: iDTRPLT mice expressing an inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (iDTR) in the megakaryocytic lineage were rendered thrombocytopenic by repeated injections of diphtheria toxin (DT). Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with donor platelets (PLT), infected with IAV, and euthanized 7 days after infection. (B) Platelet count in iDTRPLT mice with and without transfusion of seronegative (PLT neg.) or seropositive (PLT pos.) donor platelets (n = 4-12). (C-H) Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with seronegative or seropositive donor platelets in buffer, infected with IAV, and evaluated for disease severity 7 days later (n = 5). (C) Pulmonary viral load was quantified by measuring relative messenger RNA expression of IAV HA. Representative images (D) and quantification (E) of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin and scored for edema formation (arrows) and alveolar hemorrhage (*). The boxes in panel D (left panels) are shown at higher magnification in (the right panels. (F-G) Lung sections were stained for CD41 (yellow), CD144 (red), and nuclei (blue), and platelet infiltration was determined by calculating the CD41-positive area per nucleus. Representative images (F) and quantification (G). The boxes in panel F are shown at higher magnification in the corresponding panel to the immediate right. (H) Interferon response in lung tissue was quantified by measuring relative mRNA expression of interferon response factor 5 (IRF5). (I-J) Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with seronegative platelets in diluted seronegative plasma (Platelets: neg.; light blue), seronegative platelets in diluted seropositive plasma (Plasma: pos.; red), or seropositive platelets in diluted seronegative plasma (Platelets: pos.; dark blue) and infected with IAV (n = 5-6). Pulmonary viral load (I) and interferon response (J) were assessed as in panels C and H, respectively. *P < .05.

Platelets neutralize viral infection in vivo depending on their serostatus. (A) Transfusion setup: iDTRPLT mice expressing an inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (iDTR) in the megakaryocytic lineage were rendered thrombocytopenic by repeated injections of diphtheria toxin (DT). Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with donor platelets (PLT), infected with IAV, and euthanized 7 days after infection. (B) Platelet count in iDTRPLT mice with and without transfusion of seronegative (PLT neg.) or seropositive (PLT pos.) donor platelets (n = 4-12). (C-H) Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with seronegative or seropositive donor platelets in buffer, infected with IAV, and evaluated for disease severity 7 days later (n = 5). (C) Pulmonary viral load was quantified by measuring relative messenger RNA expression of IAV HA. Representative images (D) and quantification (E) of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin and scored for edema formation (arrows) and alveolar hemorrhage (*). The boxes in panel D (left panels) are shown at higher magnification in (the right panels. (F-G) Lung sections were stained for CD41 (yellow), CD144 (red), and nuclei (blue), and platelet infiltration was determined by calculating the CD41-positive area per nucleus. Representative images (F) and quantification (G). The boxes in panel F are shown at higher magnification in the corresponding panel to the immediate right. (H) Interferon response in lung tissue was quantified by measuring relative mRNA expression of interferon response factor 5 (IRF5). (I-J) Thrombocytopenic iDTRPLT mice were transfused with seronegative platelets in diluted seronegative plasma (Platelets: neg.; light blue), seronegative platelets in diluted seropositive plasma (Plasma: pos.; red), or seropositive platelets in diluted seronegative plasma (Platelets: pos.; dark blue) and infected with IAV (n = 5-6). Pulmonary viral load (I) and interferon response (J) were assessed as in panels C and H, respectively. *P < .05.

Although we did not find evidence of platelets directly binding or engulfing virus via IgG in our current study, previous reports have shown that human and murine platelets can take up virus particles.5,9 It is also possible that platelets may help infected cells to restrict viral replication via cell-cell interactions involving factors other than P-selectin. Furthermore, in vivo platelets and their IgG release may also help leukocytes or other components of the immune system to reduce viral burden via unknown mechanisms.

Our findings might be exploited to improve antibody-based therapies by loading IgG into platelets before transfusion to increase the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapies. Indeed, platelets represent optimal tools for targeted and controlled release of therapeutics superior to nanoparticle systems, such as liposomes, and platelet-based drug delivery improves drug tissue enrichment while reducing adverse effects in murine models.

In conclusion, we report that platelets potently neutralize viruses via virus-specific IgG, suggesting a novel strategy for how platelets can acquire humoral defense mechanisms and learn to fight infections.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Alice Assinger (e-mail: alice.assinger@meduniwien.ac.at) or Mattias N. E. Forsell (e-mail: mattias.forsell@umu.se).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susanne Humpeler and Bhuma Wysoudil for excellent technical expertise and Sonja Bleichert for invaluable help with experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (P24978 and P32064) and the Austrian National Bank (OENB17183) (A.A.) and The Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS-787091) and intramural funds from the Medical Faculty, Umeå University (AN 2.2.1.2-76-14) (M.N.E.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: W.C.S., M.S., S.B., M.M., J.B.K.-P., S.M., A.P., L.B., K.C.Y., U.M.H., D.P., A.A., and M.N.E.F. performed experiments; W.C.S., M.S., S.B., J.B.K.-P., A.A., and M.N.E.F. analyzed results; J.T.A., A.B., C.S.-N., and M.C.I.K. provided resources and interpreted data; and W.C.S., A.A., and M.N.E.F. prepared the figures, designed the research, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alice Assinger, Institute of Vascular Biology and Thrombosis Research, Schwarzspanierstr 17, 1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: alice.assinger@meduniwien.ac.at; and Mattias N. E. Forsell, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Umeå University, Universitetssjukhuset by 6, 6C106, 90185 Umeå, Sweden; e-mail: mattias.forsell@umu.se.

References

Author notes

A.A. and M.N.E.F. contributed equally to this work.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Seropositive platelets efficiently neutralize viral infection in vitro via their IgG. (A) Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were infected with CMV (5 hours) and incubated with buffer (control), undiluted plasma, or platelets for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative CMV immediate early (IE) expression (n = 8-14). (B) Blood donors in panel A were stratified according to their anti-CMV IgG serostatus in seronegative (neg.) and seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 7). (C) The relative number of infected HUVECs was quantified by immunofluorescence 72 hours after infection (right panel). Representative images show noninfected HUVECs (Non-inf.) CMV-infected HUVECs incubated with buffer (CMV [control]), or platelets of a seronegative (CMV+PLT neg.) or seropositive (CMV+PLT pos.) donor (left panels). Blue, DAPI; yellow, IE (CMV); red, CD61 (platelets). (D) Surface and intracellular IgG levels of human platelets were determined via flow cytometry (n = 16). (E) Total IgG levels in human citrate-theophyllin-adenosine-dipyridamole (CTAD) plasma and platelet releasate (PLTR) were examined by ELISA (n = 10). (F) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 10). (G) As in panel A, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with ticagrelor (Tica), aspirin (ASA), compstatin (Comp), or P-selectin blocking antibody (P-sel) before incubation with CMV-infected HUVECs (n = 7-13). (H) As in panel A, but CMV-infected HUVECs were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donors (n = 4-5). (I) As in panel G, but PLTR was optionally treated for 20 minutes with Comp. Alternatively, CMV-infected cells were incubated with IgG-depleted seropositive PLTR (IgG-depl), isolated IgG of seropositive PLTR (IgG only), or seronegative PLTR reconstituted with isolated seropositive IgG (+IgG) (n = 4-5). (J) Total IgG levels in naive murine plasma and PLTR were examined by ELISA (n = 8). (K) Plasma/PLTR ratio of total IgG (n = 8). (L) MDCK cells were infected with IAV (2 hours) and incubated with buffer (control) or platelets from anti-IAV IgG seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) mice for 30 minutes. Viral load was quantified 72 hours after infection via qPCR by determining relative IAV hemagglutinin (HA) expression (n = 24-26). (M) As in panel L, but seropositive platelets were optionally treated for 20 minutes with Tica, ASA, Comp, or P-sel before incubation with IAV-infected MDCK cells (n = 12-26). (N) Platelets of Tica- or control-treated mice were stimulated for 15 minutes with IAV or convulxin (CVX), and released IgG was quantified by ELISA (n = 5). (O) As in panel L, but IAV-infected MDCK cells were incubated with buffer (control) or PLTR of seronegative (neg.) or seropositive (pos.) donor mice (n = 15-17). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 between indicated groups; #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001, ####P < .0001 vs control. HPRT, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; ns, not significant; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; -, no additional treatment.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/4/16/10.1182_bloodadvances.2020001786/1/m_advancesadv2020001786f1.png?Expires=1767191341&Signature=bakYOD0F2Ug47s6DiGMe7hvJi2IBaFJDlul0j2GkYvhNL8qW7g6X0PdQLkAJuo2n5fm4UhlDLz0AfH3bPvjVfbv3YlrNPlBVmlO0OTtbRGoPYAFSeUZ-6eqfgypEFbkhZX5T68JG1U6qdvVXeiaIrIAyEFH1ydm4oc7ZTevOukqGF0ODbxvodJCevfwARfDCnEEJGhxNmdj-hySapqcSM7DAk-VjUwygyrSZSusWFhOL-F9CQDkH6Xw-7LeNAXggL-cYfmgHoeOFU3mM9LWghhLqJpumnkM6dPpQXNZe6aP4EOabgylsYCVcZ5vVb2xHFYv-0nsR-BAm0GN-vNpGiA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)