TO THE EDITOR:

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare B lineage malignancy with a high frequency of infection-related mortality. It represents 2% of leukemias1 and 2% of lymphoid neoplasms.2 Patients often present with bacterial, viral, or fungal opportunistic infections favored by the monocytopenia, neutropenia, and lymphopenia featuring the diagnosis.3,4 Immune deficiency is worsened by HCL treatments5 such as cladribine, a purine analog that depletes CD4+ T cells,6 or anti-CD20, which depletes B cells,7 both for a long period. Despite recent guidelines on HCL management in the context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic,8 data regarding outcomes of HCL patients with COVID-19 are scarce. In a cohort study including 111 patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in France, 2 patients (2%) had HCL.9 Furthermore, recent single case reports described either a concomitant diagnosis of COVID-19 and HCL10 or critical COVID-19 in a context of HCL.11 In this study, we aim to report the characteristics and outcomes of patients with HCL and COVID-19 from the EPICOVIDEHA survey,12 with a focus on patients with concomitant diagnosis of HCL and COVID-19.

The EPICOVIDEHA registry is an online survey collecting cases of COVID-19 in the context of a hematological malignancy since April 2020, and the registration of new cases is still active. The survey is promoted by the European Hematology Association - Infectious Diseases Working Party (EHA-IDWP) and has been approved centrally by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli – IRCCS – Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy (Study ID: 3226). The survey is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT04733729). The data are collected online using an electronic case report form available at www.clinicalsurveys.net (EFS Summer 2021, TIVIAN, Cologne, Germany). The following clinical and epidemiological data from patients with a laboratory-based diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection are collected: underlying conditions before SARS-CoV-2, hematological malignancy status, and management before SARS-CoV-2 infection. The severity of COVID-19 is graded according to the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the cause of mortality.13

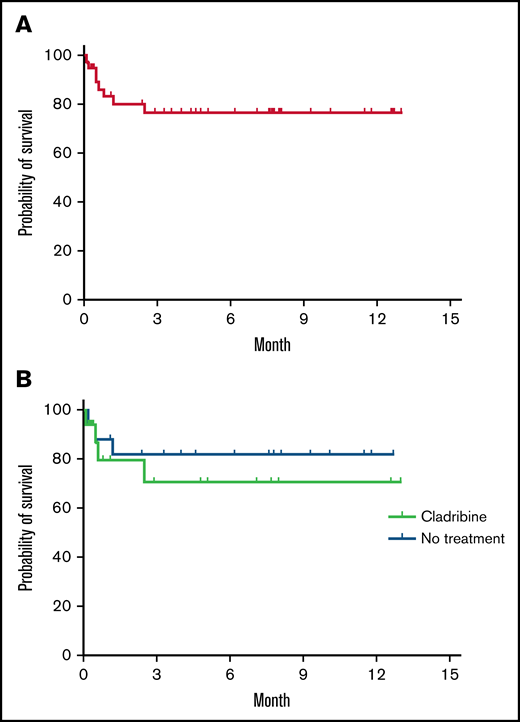

Until January 26, 2022, 40 patients with HCL and COVID-19 were reported out of the 2 422 lymphoproliferative neoplasms in the database (1.7%). Their median age was 60 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 53-67; range, 43-89), 7 patients were >70 years (18%), and 34 were male (85%; Table 1). Thirteen patients had any comorbidity (33%), mostly a cardiovascular condition. Median time between HCL and COVID-19 diagnosis was 14 months (range 0-660 months). The 7 cases diagnosed <1 month before COVID-19 were considered concomitant. HCL was diagnosed >1 month before COVID-19 for 33 patients (83%), including 5 under frontline therapy (13%), 11 in remission (28%), 15 with untreated stable disease (35%), 1 with a refractory disease (3%), and 1 with an unknown situation (3%). Regarding HCL treatments received before COVID-19, 17 patients had received cladribine (43%) at any time, including 16 as last treatment, and 3 were exposed to rituximab (8%). Time between cladribine treatment and COVID-19 was documented for 13 patients and ranged from 7 days to 18 years (median, 3 months); 8 of the patients had received cladribine <6 months before COVID-19. Due to the period covered by this study, only 5 patients were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 (13%), and variants were not documented. COVID-19 was severe for 19 cases (48%) and critical for 14 (35%). The median length of in-hospital stay was 15 days (IQR: 8-26, range 1-84), and 8 patients were still hospitalized after 30 days (20%). Fourteen patients (35%) were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), of whom 10 (24%) were intubated, and the median stay at the ICU was 15 days (IQR: 6-30, range 1-57). A total of 10 patients died, amounting to a 25% overall mortality, and of these, 9 (90%) died due to the COVID-19, 1 case for an undetermined reason. Among the 22 patients who were treatment-free for HCL, 5 had died (23%), which is similar to the proportion of 5 deaths out of 17 patients (29%) who received cladribine (Figure 1), and no death was reported among the 5 patients who were vaccinated. We found a decrease in mortality along time: in 2020, 8 deaths were observed out of 27 patients (30%) vs 2 out of 13 in 2021 (15%).

Baseline characteristics of patients with HCL and COVID-19

| Characteristics . | Sample (n = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, y | |

| Median (IQR | range) | 60 (52-67 | 43-89) |

| ≥70, n (%) | 7 (18) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 34 (85) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Obesity | 2 (5) |

| Smoking history | 3 (8) |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 9 (23) |

| Diabetes | 2 (5) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 5 (13) |

| HCL characteristics | |

| Status at COVID-19 diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Onset: concurrent diagnosis | 7 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 5 (13) |

| Remission | 11 (28) |

| Untreated stable disease | 15 (41) |

| Refractory disease | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

| Last treatment before COVID-19, n (%) | |

| No treatment | 19 (48) |

| Cladribine | 17 (43) |

| Rituximab | 2 (5) |

| Chlorambucil | 1 (3) |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (3) |

| COVID-19 characteristics | |

| Time between HCL diagnosis and COVID-19 (mo), median (IQR | range) | 14 (1-42 | 0-660) |

| Time between cladribine and COVID-19 (months), median (IQR | range) | 3 (2-32 | 0-223) |

| Vaccination | 5 (13) |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant | |

| Unknown | 32 (80) |

| Alpha | 2 (5) |

| Delta | 1 (3) |

| COVID-19 symptoms | |

| Pulmonary | 22 (55) |

| Extrapulmonary | 4 (10) |

| Pulmonary and extrapulmonary | 8 (20) |

| Severity* | |

| Asymptomatic | 3 (8) |

| Mild | 3 (8) |

| Severe | 19 (48) |

| Critical | 14 (35) |

| Neutrophiles at onset | |

| ≤500 | 6 (15) |

| 501-999 | 6 (15) |

| ≥1000 | 26 (65) |

| Lymphocytes at onset | |

| ≤200 | 8 (20) |

| 201-499 | 8 (20) |

| ≥500 | 21 (52) |

| Mortality | |

| Overall | 10 (26) |

| COVID-19 related | 9 (23) |

| Unknown reason | 1 (3) |

| Characteristics . | Sample (n = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, y | |

| Median (IQR | range) | 60 (52-67 | 43-89) |

| ≥70, n (%) | 7 (18) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 34 (85) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Obesity | 2 (5) |

| Smoking history | 3 (8) |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 9 (23) |

| Diabetes | 2 (5) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 5 (13) |

| HCL characteristics | |

| Status at COVID-19 diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Onset: concurrent diagnosis | 7 (15) |

| Frontline therapy | 5 (13) |

| Remission | 11 (28) |

| Untreated stable disease | 15 (41) |

| Refractory disease | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

| Last treatment before COVID-19, n (%) | |

| No treatment | 19 (48) |

| Cladribine | 17 (43) |

| Rituximab | 2 (5) |

| Chlorambucil | 1 (3) |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (3) |

| COVID-19 characteristics | |

| Time between HCL diagnosis and COVID-19 (mo), median (IQR | range) | 14 (1-42 | 0-660) |

| Time between cladribine and COVID-19 (months), median (IQR | range) | 3 (2-32 | 0-223) |

| Vaccination | 5 (13) |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant | |

| Unknown | 32 (80) |

| Alpha | 2 (5) |

| Delta | 1 (3) |

| COVID-19 symptoms | |

| Pulmonary | 22 (55) |

| Extrapulmonary | 4 (10) |

| Pulmonary and extrapulmonary | 8 (20) |

| Severity* | |

| Asymptomatic | 3 (8) |

| Mild | 3 (8) |

| Severe | 19 (48) |

| Critical | 14 (35) |

| Neutrophiles at onset | |

| ≤500 | 6 (15) |

| 501-999 | 6 (15) |

| ≥1000 | 26 (65) |

| Lymphocytes at onset | |

| ≤200 | 8 (20) |

| 201-499 | 8 (20) |

| ≥500 | 21 (52) |

| Mortality | |

| Overall | 10 (26) |

| COVID-19 related | 9 (23) |

| Unknown reason | 1 (3) |

Asymptomatic is for patients without clinical signs or symptoms, mild for those with non-pneumonia and mild pneumonia, severe for those with dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥30 breaths/min, SpO2 ≤ 93%, PaO2/FiO2 < 300, or lung infiltrates >50% on tomography, and critical for patients admitted in intensive care for respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction or failure.

Overall survival of patients with COVID-19 and HCL. Probability of overall survival of 39 patients with hairy cell leukemia after COVID-19 diagnosis (A) and comparison of the survival of 17 patients who had a previous treatment with cladribine with 19 patients who received no treatment (B). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis made with Prism 9 version 9.3.1 (GraphPad 2021).

Overall survival of patients with COVID-19 and HCL. Probability of overall survival of 39 patients with hairy cell leukemia after COVID-19 diagnosis (A) and comparison of the survival of 17 patients who had a previous treatment with cladribine with 19 patients who received no treatment (B). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis made with Prism 9 version 9.3.1 (GraphPad 2021).

Six out of 7 patients for whom HCL was diagnosed at the time of COVID-19 infection are described in the supplemental Table. Most of them did not suffer from any preexisting condition that could favor severe COVID-19 infection. Most of the patients required a hospitalization, and 2 of them were admitted in the ICU to receive noninvasive ventilation. All cases of HCL were diagnosed because of blood counts showing cytopenia, of which neutropenia and monocytopenia were constant. Physical examination and/or computed tomography scan showed enlarged spleen in most of patients. HCL diagnosis was confirmed by proving the coexpression of CD25, CD11c, and CD123 by the abnormal cells and/or by demonstration of BRAF V600E mutation. These findings highlight the importance of simple exams such as blood count and thorough physical examination when a patient presents with severe symptoms of COVID-19 because HCL diagnosis can be suspected when cytopenias and/or splenomegaly is present.

Here we report the first cohort of patients with HCL and COVID-19. The incidence in the survey is close to the previously reported 2% proportion of HCL among lymphoproliferative neoplasm.2 In the EPICOVIDEHA study, 64% of cases were severe/critical, and the overall mortality was 31%. The 83% of severe/critical patients reported here suggests a more severe presentation of COVID-19, but the percentage of patients who died was comparable to the entire EPICOVIDEHA cohort.14 Former studies revealed a negative impact of antitumoral treatment on infection outcomes9 ; however, in this study that included a limited number of cases with variable treatment-free period, we did not observe any effect of HCL treatment on mortality, with the limitation of the heterogeneity of our study population concerning the treatments received. The 20% of patients who stayed longer than 30 days in hospital suggests the frequent persistence of COVID-19 as reported previously.9 Besides, we observed a significant proportion of new diagnoses of HCL, revealed by splenomegaly and/or cytopenia in the situation of severe COVID-19, highlighting the importance of investigating cytopenia when present at COVID-19 diagnosis. Actually, it is common for patients with HCL to be affected by atypical and severe life-threatening infections because they present with complex immune defects affecting both cellular- and humoral-mediated immunity.15 Furthermore, the high risk of infections occurring during the initial phase of treatment is a frequent clinical challenge, and the incidence of infectious complications prior to the advent of COVID-19 ranged from 30% to 50%.4

Even if not reaching statistical significance, we observed a lower mortality over time because most of the deaths related to COVID-19 occurred in 2020. This could be explained by improvements in therapeutic management of COVID-19, including early corticosteroid therapy16 as well as the protective effects of vaccination,17 because the 5 vaccinated patients survived.

This cohort suggests that HCL may be a risk factor for severe or critical COVID-19, and future work will evaluate the protective effect of vaccination and improvement of outcomes with monoclonal antibodies and antiviral therapies recently developed.

Contribution: S.L., J.S.-G., E.R.-M., C.B., and L. Pagano contributed to study design, study supervision, and data interpretation and wrote the paper; J.S.-G. is project manager of EPICOVIDEHA; L. Pagano is principal investigator of EPICOVIDEHA; all authors recruited participants; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.L. declared miscellaneous support from Janssen, Gilead, Roche, AbbVie, Sanofi, Novartis, Actelion, and Pfizer, declared some honorarium from Gilead, and received a research grant from Janssen. J.S.-G. received speaking honoraria from Gilead Nordica outside the submitted work. R.D. reported personal fees from Takeda, Novartis, and Biotest and nonfinancial support from Gilead outside the submitted work. C.B. reported research funding from Roche and nonfinancial support from Takeda and Roche. M. Marchetti is a consultant for Gilead. M.H. received research funding from MSD, Astellas, Pfizer, Scynexis, F2G, Euroimmun, Gilead, and NIH. R.C. reported advisory activities for Janssen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Kite, Genmab, Incyte, and Kyowa-Kirin; reported speaker activities for Roche, Janssen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Takeda, and Kite; and received a research Grant from Pfizer. N.K. was board member for Gilead Science, MSD, and Pfizer, and has been speaker for Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, and Astellas Pharma. P.K. reported grants or contracts from German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF) B-FAST (Bundesweites Forschungsnetz Angewandte Surveillance und Testung) and NAPKON (Nationales Pandemie Kohorten Netz, German National Pandemic Cohort Network) of the Network University Medicine (NUM) and the State of North Rhine-Westphalia; Consulting fees from Ambu GmbH, Gilead Sciences, Mundipharma Resarch Limited, Noxxon N.V., and Pfizer Pharma; received honoraria for lectures from Akademie für Infektionsmedizin e.V., Ambu GmbH, Astellas Pharma, BioRad Laboratories, European Confederation of Medical Mycology, Gilead Sciences, GPR Academy Ruesselsheim, medupdate GmbH, MedMedia, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Scilink Comunicación Científica SC, and University Hospital and LMU Munich; participated on an advisory board for Ambu GmbH, Gilead Sciences, Mundipharma Resarch Limited, and Pfizer Pharma; has a pending patent currently reviewed at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office; and received other nonfinancial interests from Elsevier, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis online outside the submitted work. T.V. declared honorarium from Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Viatris, Teva, Sanofi Genzyme, and Zentiva and served as advisory board member for Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Sanofi Genzyme. J.B. reported honorarium and serving on advisory boards for Amgen, Janssen, and Takeda. M.-P.L. received honoraria from Gilead, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, and Novartis as member of advisory boards and for participation in symposia. O.A.C. reported grants or contracts from Amplyx, Basilea, BMBF, Cidara, DZIF, EU-DG RTD (101037867), F2G, Gilead, Matinas, MedPace, MSD, Mundipharma, Octapharma, Pfizer, and Scynexis; received consulting fees from Amplyx, Biocon, Biosys, Cidara, Da Volterra, Gilead, Matinas, MedPace, Menarini, Molecular Partners, MSG-ERC, Noxxon, Octapharma, PSI, Scynexis, and Seres; received honoraria for lectures from Abbott, Al-Jazeera Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Grupo Biotoscana/United Medical/Knight, Hikma, MedScape, MedUpdate, Merck/MSD, Mylan, and Pfizer; received payment for expert testimony from Cidara; participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Actelion, Allecra, Cidara, Entasis, IQVIA, Jannsen, MedPace, Paratek, PSI, and Shionogi; has a patent at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DE 10 2021 113 007.7); and reported other interests from DGHO, DGI, ECMM, ISHAM, MSG-ERC, and Wiley. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jon Salmanton-García, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Cologne, Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; Department I of Internal Medicine, Excellence Center for Medical Mycology (ECMM), Herderstraße 52-54, 50931 Cologne, Germany; e-mail: jon.salmanton-garcia@uk-koeln.de; and Sylvain Lamure, Department of Clinical Hematology, Montpellier University Hospital, IGMM UMR1535 CNRS, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France; e-mail: sylvain.lamure@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

S.L., J.S.-G., and E.R.-M. are joint junior authors.

C.B. and L. Pagano are joint senior authors.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (e-mail: jon.salmanton-garcia@uk-koeln.de) and senior author (e-mail: livio.pagano@unicatt.it) upon reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.