Key Points

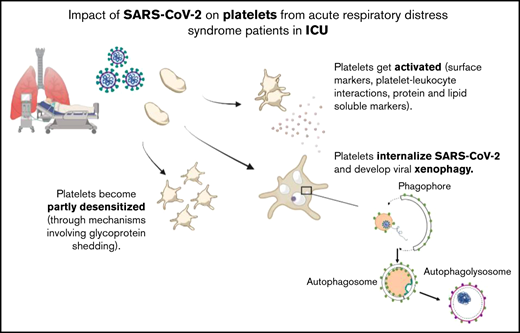

During severe COVID-19, platelets get activated and become partly desensitized through mechanisms involving glycoprotein shedding.

Platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 internalize SARS-CoV-2 and develop viral xenophagy.

Abstract

Mild thrombocytopenia, changes in platelet gene expression, enhanced platelet functionality, and presence of platelet-rich thrombi in the lung have been associated with thromboinflammatory complications of patients with COVID-19. However, whether severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) gets internalized by platelets and directly alters their behavior and function in infected patients remains elusive. Here, we investigated platelet parameters and the presence of viral material in platelets from a prospective cohort of 29 patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to an intensive care unit. A combination of specific assays, tandem mass spectrometry, and flow cytometry indicated high levels of protein and lipid platelet activation markers in the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 associated with an increase of proinflammatory cytokines and leukocyte-platelets interactions. Platelets were partly desensitized, as shown by a significant reduction of αIIbβ3 activation and granule secretion in response to stimulation and a decrease of surface GPVI, whereas plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 potentiated washed healthy platelet aggregation response. Transmission electron microscopy indicated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 particles in a significant fraction of platelets as confirmed by immunogold labeling and immunofluorescence imaging of Spike and nucleocapsid proteins. Compared with platelets from healthy donors or patients with bacterial sepsis, platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited enlarged intracellular vesicles and autophagolysosomes. They had large LC3-positive structures and increased levels of LC3II with a co-localization of LC3 and Spike, suggesting that platelets can digest SARS-CoV-2 material by xenophagy in critically ill patients. Altogether, these data show that during severe COVID-19, platelets get activated, become partly desensitized, and develop a selective autophagy response.

Introduction

Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes COVID-19, displaying variable clinical severity. To date, the pandemic has caused more than 6 million deaths worldwide (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). In patients with COVID-19, blood platelets have been shown to be activated and recruited at the site of infection and participate in the activation of the body's inflammatory response as well as in the appearance of coagulopathy-related complications.1-3 The lung is an important target of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and patients with severe COVID-19 have respiratory failure with major systemic inflammatory syndrome. A high proportion of pulmonary embolism is found in patients with severe COVID-19, up to 1 patient in 5 in some intensive care units (ICUs).4,5 Electron microscopy and histochemistry analyses have shown platelet-rich thrombi in the lung of patients who have succumbed to COVID-19.6-8 Together with other mechanisms of pulmonary circulatory failure, such as thrombotic microangiopathy, these complications might explain the relatively poor efficacy of standard prophylaxis with anticoagulants and, in the most severe cases, the failure of standard assisted ventilation techniques.9-12

Patients with severe COVID-19 are characterized by an exacerbated host immune/inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).9 In general, the pathophysiology of ARDS in its early phase combines local inflammation, accumulation, and activation of leukocytes and platelets, uncontrolled activation of coagulation, and alteration of endothelial and epithelial permeability.13 In COVID-19, the thromboembolic events are multifactorial, but endotheliopathy and thrombocytopathy are thought to take a central stage.3

Platelets act as first responders of vascular injury in concert with plasma coagulation and have an important role in inflammation and host defense.14-17 They also protect the epithelium of the pulmonary alveoli.18 Several reports indicate platelet dysfunction in patients with COVID-19, including a moderate thrombocytopenia that has been proposed as a marker of severity of the pathology as well as platelet hyperactivation and interaction with monocytes, leading to monocyte-derived tissue factor expression.19-24 A current hypothesis is that platelets are activated and recruited at the site of infection, particularly damaged endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature, and participate in the activation of the body's inflammatory response as well as in the appearance of complications related to coagulopathy. Changes in platelet activation have been associated with disease severity and mortality.21,23-25 An important question involves whether platelets are activated through endothelial cell stimulation and dysfunction, via the exacerbated inflammatory conditions, directly by SARS-CoV-2, or by a combination of these different triggers. Several viruses, including dengue and influenza, can infect megakaryocyte and have been found in platelets.26,27 SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in platelets from patients with COVID-19, suggesting the presence of viral particles.22 However, the presence of the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 binding, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), on the platelet surface is a subject of controversy.22,23,28 Recently, Koupenova et al detected viral RNA from SARS-CoV-2 in the platelets of patients with COVID-19 and demonstrated that following incubation with SARS-CoV-2 virions, platelets can actively internalize the virus by different pathways, including through endosomes, in phagocytic vacuoles, and by attachment to microparticles.29

Here we have investigated a series of platelet parameters to assess their activation and responsiveness in a cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 hospitalized in ICU. We sought to analyze the ultrastructure of the patients’ platelets and the presence of SARS-CoV-2 particles within platelets and their consequences. Our data shed new light on the behavior of platelets during severe COVID-19, including their activation, partial desensitization, and the presence of viral particles and/or proteins leading to selective autophagy/xenophagy.

Methods

Study design

Patients were enrolled in a prospective, observational study conducted at the University Hospital of Toulouse from 7 April 2020 to 18 February 2022. Patients were included in the COVID group after admission in the ICU for severe acute respiratory failure due to SARS-CoV-2 infection as confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Patients from the sepsis group were included if they were admitted for a non–COVID-19 sepsis in the ICU according to the international definition of sepsis.30 All patients from the COVID group and the sepsis group were enrolled under a study protocol approved by the Comité de protections des personnes du sud-ouest et outre-mer (CPP2020-04-042a/2020-A00972-37/20.04.08.64705). Healthy donors (38 years [interquartile range, 26-69], 50% female) were recruited under a protocol approved by the Toulouse Hospital Bio-Resources biobank, declared to the Ministry of Higher Education and Research (DC2016-2804). They were asymptomatic and had negative serology at the time of inclusion (supplemental Figure 1). Patients and healthy donors were excluded from the study if they had malignant blood disease or hemostatic disorder, were pregnant, or were majors under tutorship or guardianship or minors. All were recruited after informed consent, and study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Upon admission to ICU, baseline characteristics, biological variables, and outcome were recorded (Table 1). Patients and controls were not vaccinated for COVID-19, and there was no selection/exclusion of patients with respect to the different analysis, except that platelet functional tests were not performed if aspirin or steroids were taken within the previous 10 days before blood sampling and autophagy was not analyzed in the 3 patients who received hydroxychloroquine.

Characteristics of patients with COVID-19

| . | Severe COVID-19 (n = 29) . |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, median (range) | 63 (19-85) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 24 (82.7) |

| BMI, median (range) | 28.4 (19.7-55.6) |

| SAPS II, median (range) | 49.0 (18.0-84.0) |

| Baseline SOFA, median (range) | 5 (3-13) |

| Coexisting conditions, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 17 (58.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (34.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (17.2) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 3 (10.3) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2 (7.1) |

| Obesity | 11 (37.9) |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 5 (17.2) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (3.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (10.3) |

| Thromboembolic disease | 4 (13.8) |

| Prior antiplatelet agent | 4 (13.8) |

| Anticoagulation | 2 (7.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 3 (10.3) |

| Dexamethasone | 21 (72.4) |

| β-lactams antibiotics | 25 (86.2) |

| Neuromuscular-blocking drugs | 20 (68.9) |

| Enoxaparin | 21 (72.4) |

| Biology (at inclusion), median (range) | |

| CRP (mg/mL) | 107.0 (6.4-237.7) |

| Leukocytes (g/L) | 8.3 (4.5-29.8) |

| Lymphocytes (g/L) | 0.8 (0.2-8.3) |

| Neutrophiles (g/L) | 7.2 (3.2-23.8) |

| Platelet count (g/L) | 194 (65-521) |

| MPV (fL) | 10.3 (9.1-13.4) |

| D-dimers (ng/mL) | 910 (500-4000) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 7.0 (4.2-7.9) |

| Outcomes, median (range) or n (%) | |

| Ratio PaO2/FiO2 | 148.5 (67.0-320.0) |

| High flow oxygen, n (%) | 7 (24.2) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 22 (75.8) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (d) | 18.5 (3.0-83.0) |

| ICU LOS (d) | 17.0 (1.0-85.0) |

| Hospital LOS (d), median (range) | 26.0 (3.0-155.0) |

| Death, n (%) | 10 (34.5) |

| . | Severe COVID-19 (n = 29) . |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, median (range) | 63 (19-85) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 24 (82.7) |

| BMI, median (range) | 28.4 (19.7-55.6) |

| SAPS II, median (range) | 49.0 (18.0-84.0) |

| Baseline SOFA, median (range) | 5 (3-13) |

| Coexisting conditions, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 17 (58.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (34.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (17.2) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 3 (10.3) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2 (7.1) |

| Obesity | 11 (37.9) |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 5 (17.2) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (3.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (10.3) |

| Thromboembolic disease | 4 (13.8) |

| Prior antiplatelet agent | 4 (13.8) |

| Anticoagulation | 2 (7.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 3 (10.3) |

| Dexamethasone | 21 (72.4) |

| β-lactams antibiotics | 25 (86.2) |

| Neuromuscular-blocking drugs | 20 (68.9) |

| Enoxaparin | 21 (72.4) |

| Biology (at inclusion), median (range) | |

| CRP (mg/mL) | 107.0 (6.4-237.7) |

| Leukocytes (g/L) | 8.3 (4.5-29.8) |

| Lymphocytes (g/L) | 0.8 (0.2-8.3) |

| Neutrophiles (g/L) | 7.2 (3.2-23.8) |

| Platelet count (g/L) | 194 (65-521) |

| MPV (fL) | 10.3 (9.1-13.4) |

| D-dimers (ng/mL) | 910 (500-4000) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 7.0 (4.2-7.9) |

| Outcomes, median (range) or n (%) | |

| Ratio PaO2/FiO2 | 148.5 (67.0-320.0) |

| High flow oxygen, n (%) | 7 (24.2) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 22 (75.8) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (d) | 18.5 (3.0-83.0) |

| ICU LOS (d) | 17.0 (1.0-85.0) |

| Hospital LOS (d), median (range) | 26.0 (3.0-155.0) |

| Death, n (%) | 10 (34.5) |

None of the patients were under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The median for blood sampling was 4 days after ICU admission. No patient with the ο variant was included in the study.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; LOS, length of stay; MPV, mean platelet volume; SAPS II, simplified acute physiology score; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the patients were compared using nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney). P < .05 was statistically significant. Fischer’s test was used for morphological analysis by electronic microscopy. GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA) was used to realize the figures.

Details regarding the sources of materials and additional methods are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Characteristics of the patients with COVID-19 at admission and outcome

A total of 29 patients admitted to the ICU for severe COVID-19 who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction were included in the study. Their clinical and biological characteristics at admission are detailed in Table 1. Patients admitted for a non–COVID-19 sepsis in the ICU (sepsis group, n = 9) were also included in the study (supplemental Table 1). Eighty percent of these patients were admitted for bacterial pneumonia and 20% for urinary sepsis.

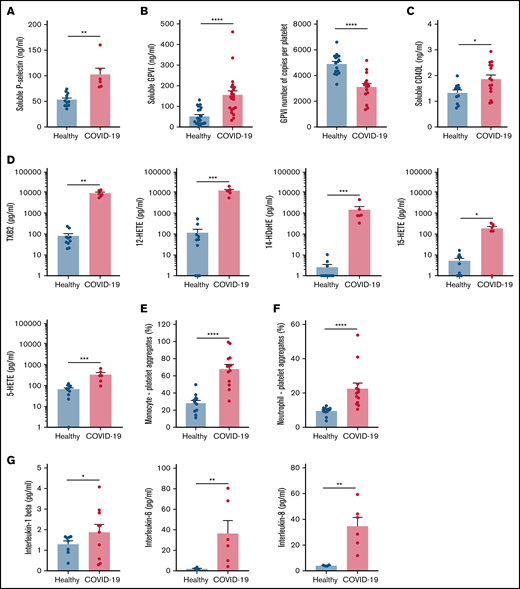

Increased soluble platelet activation markers and decreased platelet reactivity in patients with severe COVID-19

Specific soluble platelet activation markers, including soluble GPVI (sGPVI), soluble P-selectin (sCD62P), and soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L), were significantly increased in plasma of patients with COVID-19 compared with healthy controls (Figure 1A-C). Consistent with increased plasma concentration of sGPVI, the number of copies of this collagen receptor was significantly decreased at the surface of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 (Figure 1B). This result complies with a shedding of GPVI known to occur during platelet activation. The plasma concentration of eicosanoids derived from the metabolism of arachidonic acid during platelet activation through the cyclooxygenases and the lipoxygenases pathways was then analyzed. The plasma level of thromboxane B2 (TxB2), the stable metabolite of thromboxane A2 (TXA2), and the lipoxygenase product 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) was very high in patients with severe COVID-19 and low in controls (Figure 1D). Other lipoxygenase products such as 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE), 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE), and 14-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid (14-HDoHE) were also significantly elevated in patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 1D).

Platelet activation markers in patients with severe COVID-19 compared with controls. Soluble markers of platelet activation including soluble P-selectin (A), soluble GPVI (B, left panel), and soluble CD40L (C) were quantified in the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 and healthy donors (A: n = 12 healthy donors and n = 6 patients; B: n = 20 healthy donors and n = 22 patients; C: n = 11 healthy donors and n = 15 patients). The number of copies of platelet surface GPVI was also quantified (B, right panel, n = 16 healthy donors and n = 15 patients). Eicosanoids (D) known to be produced by activated platelets, including TXB2, 12-HETE, 14-HDoHE, 15-HETE, and 5-HETE, were quantified in plasma from 7 patients with severe COVID-19 and 6 healthy donors using a mass spectrometry-based targeted lipidomic approach. The presence of heterotypic monocyte-platelet (E) and neutrophil-platelet (F) aggregates were quantified by flow cytometry in 13 patients with severe COVID-19 and 11 healthy donors. The concentrations of IL-1beta, IL-6, and IL-8 were also quantified using appropriate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (G) in the plasma of 6 to 10 patients with severe COVID-19 and 4 to 8 healthy donors. Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Platelet activation markers in patients with severe COVID-19 compared with controls. Soluble markers of platelet activation including soluble P-selectin (A), soluble GPVI (B, left panel), and soluble CD40L (C) were quantified in the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 and healthy donors (A: n = 12 healthy donors and n = 6 patients; B: n = 20 healthy donors and n = 22 patients; C: n = 11 healthy donors and n = 15 patients). The number of copies of platelet surface GPVI was also quantified (B, right panel, n = 16 healthy donors and n = 15 patients). Eicosanoids (D) known to be produced by activated platelets, including TXB2, 12-HETE, 14-HDoHE, 15-HETE, and 5-HETE, were quantified in plasma from 7 patients with severe COVID-19 and 6 healthy donors using a mass spectrometry-based targeted lipidomic approach. The presence of heterotypic monocyte-platelet (E) and neutrophil-platelet (F) aggregates were quantified by flow cytometry in 13 patients with severe COVID-19 and 11 healthy donors. The concentrations of IL-1beta, IL-6, and IL-8 were also quantified using appropriate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (G) in the plasma of 6 to 10 patients with severe COVID-19 and 4 to 8 healthy donors. Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Platelet activation was also highlighted by a significant increase in circulating heterotypic monocyte-platelet (Figure 1E) and neutrophil-platelet (Figure 1F) aggregates in the COVID-19 patient group. As expected, this was associated with an increase in the blood concentration of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 (Figure 1G).

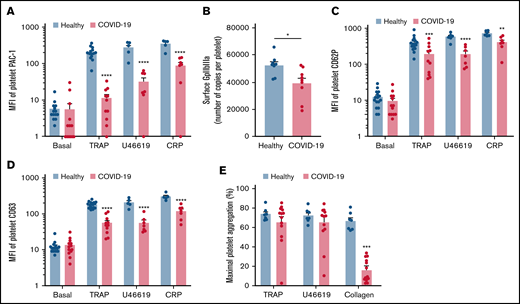

We then investigated the level of activation of the platelet-specific αIIbβ3 integrin (GpIIbIIIa) by binding of the PAC1 antibody on the platelet surface as well as the membrane expression of the α-granule secretion marker P-selectin (CD62P) and the dense granule secretion marker CD63 at rest or following stimulation. Nonstimulated platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 and controls showed comparable levels of activated αIIbβ3 as well as CD62P and CD63 membrane expression (Figure 2A-D). While the basal surface expression of GpIaIIa and GpIb was unchanged (supplemental Figure 2), the expression of αIIbβ3 per platelet was significantly decreased in patients with COVID-19, suggesting the occurrence of a shedding process (Figure 2B). We next assessed platelet reactivity following stimulation by collagen-related peptide (CRP), thrombin receptor agonist peptide (TRAP), or the stable analog of TXA2 (U46619). The intensity of activation of the fibrinogen receptor αIIbβ3 was significantly reduced in patients with severe COVID-19 in response to all agonists tested (Figure 2A). Similarly, although the number of α-granule was comparable in the 2 groups (supplemental Figure 2A), their secretion as well as that of dense granules was significantly reduced in the group with severe COVID-19 (Figure 2C-D). These results suggest that platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 have a significant reduction of reactivity to physiological agonists. The maximal platelet aggregation response measured by light transmittance aggregometry after 6 minutes of stimulation tended to decrease in response to U46619 and TRAP and was significantly reduced following collagen stimulation in patients with severe COVID-19 (Figure 2E). Overall, these data suggest that platelets get activated and partly desensitized during severe COVID-19. Although the number of patients was limited, correlative studies (supplemental Table 2) suggest that the sGPVI level is associated with thromboembolic events and that high TRAP-induced platelet aggregation response correlated to patient death.

Platelet reactivity following stimulation in patients with severe COVID-19 compared with healthy donors. Platelet-rich plasma from 15 healthy donors and 16 patients with severe COVID-19 was stimulated or not with TRAP (50 µM), U46619 (5 µM), and CRP (0.9 µg/mL) for 10 minutes in nonstirring conditions at 37°C, and activation of αIIbβ3 (GpIIb-IIIa) was assessed by flow cytometry using PAC-1 antibody (A). The number of copies of surface GpIIb-IIIa in resting platelets was also quantified (B, n = 8 healthy donors and n = 9 patients). The surface expression of P-selectin (CD62P), a marker of α-granules secretion (C), and CD63, a marker of dense granules secretion (D), was quantified in resting and stimulated platelets. The platelet aggregation response (% of maximal platelet aggregation) from healthy donors and patients with severe COVID-19 was also assessed by light transmission aggregometry in response to TRAP (50 µM), U46619 (1 µM), and collagen (0.75 µg/mL) for 10 minutes in stirring conditions (E). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Platelet reactivity following stimulation in patients with severe COVID-19 compared with healthy donors. Platelet-rich plasma from 15 healthy donors and 16 patients with severe COVID-19 was stimulated or not with TRAP (50 µM), U46619 (5 µM), and CRP (0.9 µg/mL) for 10 minutes in nonstirring conditions at 37°C, and activation of αIIbβ3 (GpIIb-IIIa) was assessed by flow cytometry using PAC-1 antibody (A). The number of copies of surface GpIIb-IIIa in resting platelets was also quantified (B, n = 8 healthy donors and n = 9 patients). The surface expression of P-selectin (CD62P), a marker of α-granules secretion (C), and CD63, a marker of dense granules secretion (D), was quantified in resting and stimulated platelets. The platelet aggregation response (% of maximal platelet aggregation) from healthy donors and patients with severe COVID-19 was also assessed by light transmission aggregometry in response to TRAP (50 µM), U46619 (1 µM), and collagen (0.75 µg/mL) for 10 minutes in stirring conditions (E). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

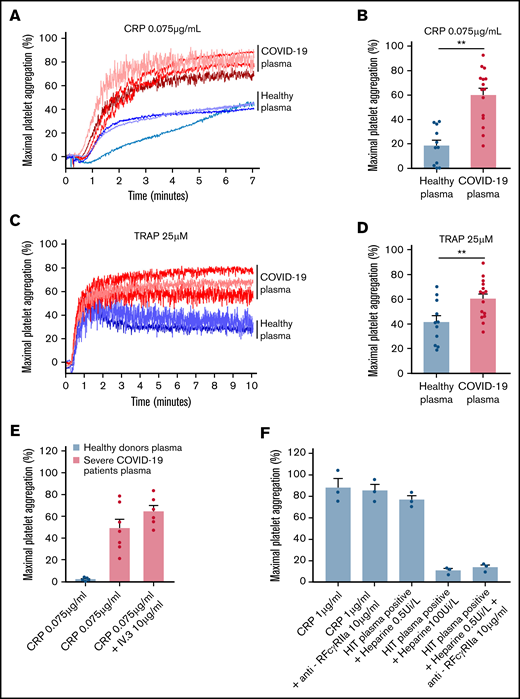

To check whether the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 would modify the aggregation response of platelets from healthy donors, we performed cross-aggregation tests. Washed platelets from healthy donors were resuspended in plasma from either healthy donors or patients with COVID-19 and stimulated by low doses of CRP (0.075 µg/mL) or TRAP (25 µM). As shown Figure 3A-D, the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 significantly potentiated platelet aggregation induced by CRP (Figure 3A-B) or TRAP (Figure 3C-D). This potentiating effect, which may contribute to platelet desensitization in patients with severe COVID-19, was not due to platelet FcγRIIA triggering because specific blockade of this Fc receptor with a neutralizing antibody did not impair the effect of the COVID-19 plasma (Figure 3E). As expected, this neutralizing antibody totally inhibited platelet aggregation induced by plasma from patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Figure 3E). Addition of plasma from patients with COVID-19 for 30 minutes on healthy resting platelets weakly decreased αIIbβ3 and GPVI surface expression and faintly increased dense granule secretion (supplemental Figure 3).

Effect of plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 on washed healthy platelet aggregation response. Washed platelets from 6 healthy donors were resuspended in plasma from 11 to 15 patients with severe COVID-19 or 9 healthy donors. The platelet aggregation response (% of maximal platelet aggregation) was then assessed by light transmission aggregometry in response to low doses of CRP (0.075 µg/mL) (A-B) and TRAP (25 µM) (C-D) for 10 minutes. Representative aggregation traces are shown (A, C) as well as the quantification of maximal platelet aggregation response (B, D). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual plasma. **P < .01 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The potential impact of FcγRIIA receptor on the potentiation of plasma of patients with severe COVID-19 on CRP-induced platelet aggregation was assessed by using the IV.3 neutralizing antibody (E). As a positive control of the IV.3 antibody efficiency, 3 sera from patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) were used in the presence of heparin (0.5 IU/mL) to induce healthy platelet aggregation via FcγRIIA. The specificity of the reaction was assessed by addition of a large excess of heparin to impair platelet aggregation induced by HIT sera (F).

Effect of plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 on washed healthy platelet aggregation response. Washed platelets from 6 healthy donors were resuspended in plasma from 11 to 15 patients with severe COVID-19 or 9 healthy donors. The platelet aggregation response (% of maximal platelet aggregation) was then assessed by light transmission aggregometry in response to low doses of CRP (0.075 µg/mL) (A-B) and TRAP (25 µM) (C-D) for 10 minutes. Representative aggregation traces are shown (A, C) as well as the quantification of maximal platelet aggregation response (B, D). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual plasma. **P < .01 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The potential impact of FcγRIIA receptor on the potentiation of plasma of patients with severe COVID-19 on CRP-induced platelet aggregation was assessed by using the IV.3 neutralizing antibody (E). As a positive control of the IV.3 antibody efficiency, 3 sera from patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) were used in the presence of heparin (0.5 IU/mL) to induce healthy platelet aggregation via FcγRIIA. The specificity of the reaction was assessed by addition of a large excess of heparin to impair platelet aggregation induced by HIT sera (F).

Platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 contain viral material

Ultrastructural analysis of platelets from 10 patients with severe COVID-19 by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicated the presence of characteristic crown-like structures of the expected size of SARS-CoV-2 (80-120 nm of diameter) in 22.7 ± 6.3% of their platelets (Figure 4A-B). Such characteristic viral-like particles identified and quantified on the basis of specific criteria were observed in platelets from all 10 patients tested but not in platelets from patients with bacterial sepsis or healthy donors (Figure 4B). The presence of SARS-CoV-2 proteins in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 was confirmed by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy using a specific Spike protein antibody (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 4). Moreover, immunogold labeling of Spike and nucleocapsid applied to TEM showed the presence of these viral proteins in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 (Figure 4D) whereas no labeling was found in control platelets (supplemental Figure 5). Spike labeling was often found in large vesicle-like structures whereas nucleocapsid labeling was mainly in smaller vesicles, suggesting different processing of these proteins.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Analysis of transmission electron micrographs of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 revealed the presence of characteristic crown-like structures reminiscent to SARS-CoV-2 particles (A). Images shown are from 3 patients and are representative of the 10 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. Viral-like particles were identified on the basis of specific criteria, including the size of the viral particle (100 nm ± 20%), the presence of a white halo around the particle, the size of the endosomal structure containing the viral particle (between 100 and 150 nm), and the crown-like spikes on the surface of the particle. Quantitative analysis was performed on transmission electron micrographs (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets from healthy controls, patients with bacterial sepsis, and patients with severe COVID-19 containing viral-like particles was quantified (B). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein within platelets was analyzed by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (C). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images from 6 healthy donors and 6 patients are shown (bar represents 5 µm). Immunogold labeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike (D) and nucleocapsid (E) proteins analyzed by TEM confirmed the presence of these viral proteins in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Representative images from 3 different patients are shown for illustration.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Analysis of transmission electron micrographs of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 revealed the presence of characteristic crown-like structures reminiscent to SARS-CoV-2 particles (A). Images shown are from 3 patients and are representative of the 10 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. Viral-like particles were identified on the basis of specific criteria, including the size of the viral particle (100 nm ± 20%), the presence of a white halo around the particle, the size of the endosomal structure containing the viral particle (between 100 and 150 nm), and the crown-like spikes on the surface of the particle. Quantitative analysis was performed on transmission electron micrographs (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets from healthy controls, patients with bacterial sepsis, and patients with severe COVID-19 containing viral-like particles was quantified (B). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein within platelets was analyzed by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (C). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images from 6 healthy donors and 6 patients are shown (bar represents 5 µm). Immunogold labeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike (D) and nucleocapsid (E) proteins analyzed by TEM confirmed the presence of these viral proteins in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Representative images from 3 different patients are shown for illustration.

Specific platelet ultrastructural changes in patients with severe COVID-19

Analysis of platelet ultrastructure by TEM revealed that several platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited enlarged surface areas of low electron density reminiscent of vesicular structures or open canalicular system (OCS) (Figure 5A). These vesicle-like structures were rare in platelets from patients admitted to the ICU for bacterial sepsis (Figure 5A). Analysis of electron micrographs of platelet complete cross-sections indicated that 63.1 ± 12.5% of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited enlarged vesicle-like structures (Figure 5B). To check whether those structures would belong to the surface-connected and dilated OCS, we used specific labeling with the electron-dense extracellular tracer tannic acid. This labeling revealed that the vesicle-like structures observed in platelets from patients with COVID-19 were not in continuity with the plasma membrane and the OCS because they showed no tannic acid labeling (Figure 5C). These enlarged vesicle-like structures suggest a modification of the intracellular trafficking machinery in platelet from severe COVID-19 that could be linked to viral particle uptake because Spike was found in such vesicles (Figure 4D). The platelet cross-sectional area and the number of vesicle-like structures per platelet were comparable among the 3 groups (Figure 5D-E). In contrast, the vesicle-like area/platelet area ratio and the mean area of vesicle-like structures were significantly increased in the group with severe COVID-19 (Figure 5F-G). The electron micrograph analysis also allowed us to quantify the number of microtubules and pseudopodia emitted as signs of platelet activation. Following platelet activation, microtubules rapidly reorganize and become much less visible by TEM. The number of visible platelet microtubules was significantly decreased in both the group with bacterial sepsis and the group with severe COVID-19 compared with controls, suggesting platelet activation (Figure 5H). Of note, 74% of platelets exhibiting viral-like particles had invisible microtubules. Consistent with the decrease in microtubules, the number of pseudopodia significantly increased in the groups with bacterial sepsis and severe COVID-19 (Figure 5I). These data point to platelet activation in the 2 groups of patients whereas only platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited enlarged vesicle-like structures.

Specific ultrastructural modifications in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. PRP from healthy donors (n = 6), septic patients without COVID-19 (bacterial sepsis, n = 4), and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) were fixed and analyzed by TEM (A). Representative electron micrographs at different magnification are shown. Different parameters and cellular elements were quantified using electron micrographs of platelet complete cross-sections (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets exhibiting enlarged vesicles (vesicle surface/platelet cross section surface ratio > 6.1, which is the upper quartile for control platelets) was quantified (B). **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. To check whether the vesicle-like structures were part of the OCS, platelet-rich plsma from 4 healthy donors and 6 patients with severe COVID-19 was fixed and stained with tannic acid before analysis by TEM (C). Representative transmission electron micrographs are shown (the top two from healthy controls and the bottom ones from patients with COVID-19). Magnifications of selected areas (×10 000) show that the vesicles were not labeled with tannic acid, excluding their belonging to the OCS (see also supplemental Figure 11). The cross-sectional surface (D), the number of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (E), the surface of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (F), and the vesicle-like surface/platelet cross-section surface ratio (G) were quantified. ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence or absence of microtubules (H) and pseudopodia (I) per platelet cross-section was also quantified as parameters of platelet activation. Fischer’s test was used for statistical analysis.

Specific ultrastructural modifications in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. PRP from healthy donors (n = 6), septic patients without COVID-19 (bacterial sepsis, n = 4), and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) were fixed and analyzed by TEM (A). Representative electron micrographs at different magnification are shown. Different parameters and cellular elements were quantified using electron micrographs of platelet complete cross-sections (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets exhibiting enlarged vesicles (vesicle surface/platelet cross section surface ratio > 6.1, which is the upper quartile for control platelets) was quantified (B). **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. To check whether the vesicle-like structures were part of the OCS, platelet-rich plsma from 4 healthy donors and 6 patients with severe COVID-19 was fixed and stained with tannic acid before analysis by TEM (C). Representative transmission electron micrographs are shown (the top two from healthy controls and the bottom ones from patients with COVID-19). Magnifications of selected areas (×10 000) show that the vesicles were not labeled with tannic acid, excluding their belonging to the OCS (see also supplemental Figure 11). The cross-sectional surface (D), the number of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (E), the surface of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (F), and the vesicle-like surface/platelet cross-section surface ratio (G) were quantified. ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence or absence of microtubules (H) and pseudopodia (I) per platelet cross-section was also quantified as parameters of platelet activation. Fischer’s test was used for statistical analysis.

Large LC3-positive structures characterize platelets from patients with severe COVID-19, evidence for xenophagy

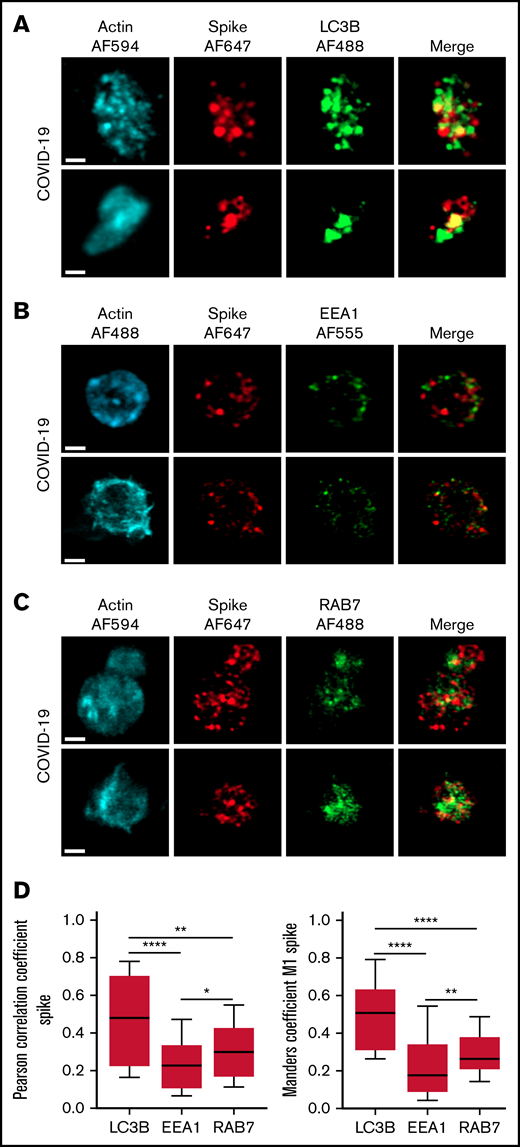

The autophagy pathway can act as an intrinsic antiviral defense mechanism to degrade viral material through a process called xenophagy (foreign-eating) or virophagy.31 Selective autophagy allows delivery of trapped viral cargo to the lysosome for degradation through autophagosome formation.31,32 Immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy analysis clearly indicated the presence of large LC3-positive puncta in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 compared with control platelets and platelets from patients with bacterial sepsis (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 6A). A 3-dimensional representation of LC3-positive structures highlights their important size and tubular nature (Figure 6B). Consistent with this observation, LC3BII, a standard marker for autophagosomes and autolysosomes generated by conjugation of cytosolic LC3BI to phosphatidylethanolamine, was strongly present in platelets of patients with severe COVID-19 compared with control platelets and platelets from patients with bacterial sepsis (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 6B). The LC3BII/actin ratio and, to a lesser extent, the LC3BI/actin ratio were significantly increased in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 compared with platelets from controls and patients with bacterial sepsis (Figure 6C, right panel; supplemental Figure 6C). Consistent with western blot and imaging analysis, immunogold labeling indicated an increase of LC3B in platelets from patients with COVID-19 (Figure 6D) and the presence of LC3B around phagosome-like structures (Figure 6E). Autolysosomes can derive from fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes or from fusion with late endosomes structures, which may give rise to LAPosomes that subsequently fuse with lysosomes. To investigate the origin of these LC3-positive vesicles, we searched for autophagy patterns. TEM analysis demonstrated the presence of characteristic macroautophagic structures, including elongation membranes (phagophores), autophagosomes, and autophagolysosomes, in a substantial fraction of platelets from the 10 patients with COVID-19 analyzed (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 7). These structures were not visible or were rare in control platelets. Super-resolution confocal microscopy analysis demonstrated a significant degree of colocalization of Spike and LC3B in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 as shown by a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.667 ± 0.142 and a Manders’ coefficient of 0.521 ± 0.209 (Figure 7A,D). There was much less colocalization of Spike with the early endosome marker EE1 but a partial colocalization with the late endosome marker Rab7 (Figure 7B-D), suggesting the presence of structures derived from the endosomal pathway potentially related to LAPosomes or amphisomes. Finally, co-labeling experiments with fibrinogen and CD63 excluded the presence of Spike in platelet dense and α granules (supplemental Figure 8).

Presence of LC3B-positive vesicles in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Washed platelets from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) were fixed and labeled with a specific anti-LC3B antibody and analyzed by super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (A). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images are shown (bar represents 1 µm). Images reconstructed in 3 dimensions (B) show LC3B spatial distribution in platelets of healthy control and patients with severe COVID-19. A representative western blotting analysis shows the level of LC3B-I and LC3B-II in platelets from 4 heathy donors (H1-H4) representative of 5 and from 4 patients with severe COVID-19 (P1-P4) representative of 7 (C, left panel). The exposure time was adjusted to efficiently distinguish the LC3BI and LC3BII forms. The quantification of the LC3B/actin ratio for LC3B-I and LC3B-II from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) is shown in the right panel. Results are mean ± SEM. **P < .01 ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Immunogold labeling of LC3B protein analyzed by TEM shows the number of gold particles by cross-section (30 from n = 3 healthy donors [10 for each] and 30 from n = 3 patients with severe COVID-19 [10 for each]) (D). Results are mean ± SEM. ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of LC3B associated with a large vacuole reminiscent of autophagosome (arrows and magnification insert) is shown in a platelet from patient with severe COVID-19 (E). Representative TEM sections of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) showing structures typical of elongation membrane (EM), autophagosome (AP), and autophagolysosome-like (AL) (F).

Presence of LC3B-positive vesicles in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Washed platelets from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) were fixed and labeled with a specific anti-LC3B antibody and analyzed by super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (A). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images are shown (bar represents 1 µm). Images reconstructed in 3 dimensions (B) show LC3B spatial distribution in platelets of healthy control and patients with severe COVID-19. A representative western blotting analysis shows the level of LC3B-I and LC3B-II in platelets from 4 heathy donors (H1-H4) representative of 5 and from 4 patients with severe COVID-19 (P1-P4) representative of 7 (C, left panel). The exposure time was adjusted to efficiently distinguish the LC3BI and LC3BII forms. The quantification of the LC3B/actin ratio for LC3B-I and LC3B-II from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) is shown in the right panel. Results are mean ± SEM. **P < .01 ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Immunogold labeling of LC3B protein analyzed by TEM shows the number of gold particles by cross-section (30 from n = 3 healthy donors [10 for each] and 30 from n = 3 patients with severe COVID-19 [10 for each]) (D). Results are mean ± SEM. ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of LC3B associated with a large vacuole reminiscent of autophagosome (arrows and magnification insert) is shown in a platelet from patient with severe COVID-19 (E). Representative TEM sections of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) showing structures typical of elongation membrane (EM), autophagosome (AP), and autophagolysosome-like (AL) (F).

Localization of Spike protein in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. The intraplatelet localization of Spike protein was investigated by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module using a specific anti-Spike antibody. Its colocalization with LC3B, a marker of autophagosomes (A), EEA1, a marker of early endosomes (B), and Rab7, a marker of late endosomes (C), was analyzed. Representative images from 5 different patients with severe COVID-19 are shown (bar represents 1 µm). Quantification was performed from the analysis of 30 to 40 platelets from each of the 5 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Manders’ coefficient calculations are shown (D). *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Localization of Spike protein in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. The intraplatelet localization of Spike protein was investigated by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module using a specific anti-Spike antibody. Its colocalization with LC3B, a marker of autophagosomes (A), EEA1, a marker of early endosomes (B), and Rab7, a marker of late endosomes (C), was analyzed. Representative images from 5 different patients with severe COVID-19 are shown (bar represents 1 µm). Quantification was performed from the analysis of 30 to 40 platelets from each of the 5 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Manders’ coefficient calculations are shown (D). *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

The high incidence of thromboembolic events in patients with severe COVID-19 is now well established and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.4,21,25,33 -35 The mechanisms underlying thrombotic complications are multifactorial, however, with a central role of thrombocytopathy and endotheliopathy.3,25,36 Platelets are emerging as important players in the coordinated action of the uncontrolled inflammatory and thrombotic response observed in SARS-CoV-2–mediated severe disease.22-24 Here, we show that patients with severe COVID-19 with ARDS have high levels of plasma platelet activation markers, including sCD40L, sGPVI, and sP-selectin. Our study confirms the significant increase in circulating heterotypic monocyte-platelet and neutrophil-platelet aggregates highlighting in vivo platelet activation.37 These aggregates are observed in thromboinflammatory diseases such as sepsis, acute lung injury, and cardiovascular diseases38 and are associated with increased mortality in elderly patients with sepsis.39 Eicosanoids produced by activated platelets such as TXB2 and 12-HETE were present at a high level in patient plasma. Of note, elevated levels of TXB2 were observed in bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with COVID-19, suggesting platelet contribution.40 The concentration of other members of this family of bioactive lipids produced by the LOX pathway by either activated platelets or immune cells such as 5-HETE and 15-HETE were also very high in the plasma from patients with severe COVID-19. Consistent with previous studies,22,41-43 our cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited high levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. This first set of data confirms platelet activation in patients with severe COVID-19 in complement to previous studies.22 -24,44 Importantly, when platelet reactivity was tested ex vivo, we observed a partial but significant desensitization to physiological agonists. The significant decrease in the activation of integrin αIIbβ3 assessed by PAC-1 labeling after stimulation correlated with a decrease in the number of αIIbβ3 copies on the surface of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Moreover, the secretion of α and dense granules was also significantly reduced as well as platelet aggregation following collagen activation. A drop in the number of collagen receptor GPVI copies on the surface of platelets was associated with an increase of sGPVI, indicating a shedding after proteolytic cleavage known to occur following contact of the receptor with its ligand or binding antibodies or as a result of elevated shear stress in the microcirculation. Acquired platelet GPVI receptor dysfunction in critically ill patients, particularly in the early phase of sepsis, has recently been described.45 The disintegrin and metalloprotease ADAM10 is known to cleave the extracellular domain of GPVI.46 Factor Xa can also mediate coagulation-dependent shedding of GPVI.47 The proteasic activity of ADAM10, which increases following platelet activation, may explain the acquired platelet GPVI dysfunction we observed in cases of severe COVID-19 as a potential programmed downregulation function of the receptor.48,49

Manne et al23 have also reported a reduced activation of αIIbβ3 in patients with COVID-19. Reduction of platelet procoagulant response and platelet desensitization to TRAP have been described as well as a hyporesponsive platelet phenotype associated with adverse outcome in COVID-19.50,51 Of note, hypoxia may be involved in the reduction of platelet responses.52 However, several reports have clearly shown a hyperactivity of platelets from patients with COVID-19.22-24 An explanation for this discrepancy may be that the partial desensitization observed in our cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 may have taken place secondary to the thromboinflammatory events because the median for blood sampling was 4 days after ICU admission whereas it was <72 hours in studies showing platelet hyperactivity. Consistent with this, activation of normal platelets by CRP or TRAP in the platelet-poor plasma from patients with severe COVID-19 induced a significant potentiation of the aggregation response, highlighting the prothrombotic nature of patient plasma. Moreover, analysis of the ultrastructure of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 indicated a decrease in the number of microtubules and an increase in pseudopodia emitted, which are signs of platelet activation. Overall, these data indicate that platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 undergo in vivo activation and then become partly desensitized.

Interestingly, using TEM, immunogold labeling, and immunofluorescence approaches, we found the presence of viral-like particles and viral proteins in a significant proportion of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Viral-like particles were found in 22.7% of platelets from the 10 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. They were also recently observed in a significant percentage of circulating platelets from 3 patients with COVID-19.53 How SARS-CoV-2 enters the platelets remains elusive. While Manne et al23 and Zaid et al22 did not find ACE2 mRNA or protein in patient platelets, Zhang et al28 found that they express ACE2 as well as its partner, the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), which is known to proteolytically cleave and activate the viral Spike protein to facilitate virus entry. Koupenova et al29 found low levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 proteins in platelets and detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in platelets from patients with COVID-19. They also showed that following in vitro incubation with SARS-CoV-2 virions, platelets internalize the virus through endosomes, in phagocytic vacuoles, and by attachment to microparticles. Moreover, an ACE2-independent mechanism allowing interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with megakaryocyte and platelet has been suggested.54 Finally, CD147, which is expressed in platelets,55 has been proposed as a potential receptor or coreceptor for SARS-CoV-2 that can promote virus entry into host cells.56 Thus, evidence is accumulating that platelets can uptake SARS-CoV-2 by different mechanisms.

Analysis of Spike protein by immunogold labeling in TEM indicated its presence in large vesicles. Compared with control platelets or platelets from patients with bacterial sepsis, platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibited a higher proportion of large vesicles that were not in continuity with the plasma membrane and the OCS. These vesicles are reminiscent to the endocytic vesicle described by TEM in platelets infected by HIV.57,58 Recently, it was shown that platelets engulf HIV-1 virion and traffic them from the endocytic pathway to an LC3-decorated compartment, which may correspond to LC3-associated phagosomes or LAPosomes.59 Here we found that platelets from the 10 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed exhibited characteristic autophagic structures. Cross-talk between host autophagy and viruses has been frequently reported,31,60 including for SARS-COV-2.61 Compared with control platelets or platelets from bacterial sepsis patients, the strong presence of LC3B-decorated large tubular structures in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 associated with a significant increase in LC3B-II levels and a colocalization of LC3B and Spike strongly suggest that selective autophagy recognizes intracellular viral components to degrade them via autophagosomes and autophagolysosomes. This processs, also termed xenophagy or, in the case of viruses, virophagy, is known to play an important role in the resistance to infections.31 Besides entry of the virus itself, platelets may uptake circulating viral proteins including Spike.62 A recent study has shown that Spike protein can engage Gp1b receptor to activate platelets through PKC and PI3K/Akt pathways and promote platelet–monocyte interactions.63 While our study indicates that platelet xenophagy/virophagy is part of the defense mechanisms against SARS-CoV-2 virus, it remains to be investigated whether this process can amplify platelet activation, as proposed for autophagy,64 or can contribute to their desensitization. Moreover, the impact of the highly inflammatory context on selective autophagy is unknown.

The intraplatelet processing of soluble viral protein and the whole SARS-COV-2 may require different pathways. Moreover, modulation of these autophagy-related pathways by the virus to escape degradation may also occur.31 Mechanisms governing xenophagy in response to viral infection are of particular current interest in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our data showing a partial colocalization of Spike with Rab7 suggests the formation of structures derived from the endocytic pathway that may be related to LAPosomes. The endolysosomal and autophagic pathways may coexist and interconnect in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. This is consistent with the different modes of entry of the virus recently described.29 Thus, platelets have conserved a specialized form of selective autophagy to target viruses or components thereof to autophagosomes and autophagolysosomes for elimination. Of note, platelets have the ability to process exogenous antigens to antigenic peptides through a vacuolar (phagosome-to-cytosol) pathway and present antigen via histocompatibility complex class I.65,66 An attractive hypothesis is that platelets could contribute to T-cell triggering to promote SARS-CoV-2 protective immune responses. Increasing these beneficial properties of platelets while minimizing their deleterious proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects should be of clinical benefit.

In conclusion, platelets from patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 ARDS are activated and get partly desensitized through mechanisms such as shedding of surface glycoproteins such as GPVI. Ultrastructural analysis of patient platelets demonstrates for the first time in vivo that a significant proportion of platelets internalize SARS-CoV-2 and viral material and develop xenophagy through the endolysosomal and autophagic pathways, contributing to viral material clearance.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the personnel of Genotoul Lipidomic facility of I2MC (P. Lefaouder and J. Bertrand-Michel), Cytometry facility of I2MC (E. Riant and A. Zakaroff-Girard), Cellular Imaging Facility–I2MC/TRI Platform (R. Flores-Flores), and WE-MET facility–I2MC (A. Lucas and C. Bernis). The authors also thank all members of the "B.P. team" for helpful discussions, the Toulouse Rangueil Medico-Surgical Intensive Care Unit, and the patients and their families.

This study was supported by research funding from Inserm and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DEQ20170336737) and by the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (SFAR).

Authorship

Contribution: B. Payrastre, C.G., F.V.-B., and V. Minville conceived and designed the work; F.V.-B., J.A.D., and M.P. supervised patient inclusion, clinical management duties, and ethical approvals; C.G., J.A.D., M.P., F.V.-B., and B. Payre designed the experiments and executed most of the experiments; C.G., J.A.D., A.R., P.S., S.V., V. Mémier, F.V.-B., and B. Payrastre compiled, analyzed, and interpreted data; C.G., B. Payrastre, and F.V.-B. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and critically edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fanny Vardon-Bounes, Anesthesiology and Critical Care Unit, University Hospital of Toulouse, 1 Ave du Pr J. Poulhès, 31059 Toulouse Cedex, France; e-mail: bounes.f@chu-toulouse.fr; and Bernard Payrastre, Inserm UMR1297, Institut des Maladies Métaboliques et Cardiovasculaires, 1 Ave du Pr J. Poulhès, 31059 Toulouse Cedex, France; e-mail: bernard.payrastre@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

B. Payrastre and F.V.-B. are joint senior authors.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Fanny Vardon-Bounes (bernard.payrastre@inserm.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Analysis of transmission electron micrographs of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 revealed the presence of characteristic crown-like structures reminiscent to SARS-CoV-2 particles (A). Images shown are from 3 patients and are representative of the 10 patients with severe COVID-19 analyzed. Viral-like particles were identified on the basis of specific criteria, including the size of the viral particle (100 nm ± 20%), the presence of a white halo around the particle, the size of the endosomal structure containing the viral particle (between 100 and 150 nm), and the crown-like spikes on the surface of the particle. Quantitative analysis was performed on transmission electron micrographs (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets from healthy controls, patients with bacterial sepsis, and patients with severe COVID-19 containing viral-like particles was quantified (B). Results are mean ± SEM; each circle represents an individual. **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein within platelets was analyzed by immunofluorescence and super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (C). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images from 6 healthy donors and 6 patients are shown (bar represents 5 µm). Immunogold labeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike (D) and nucleocapsid (E) proteins analyzed by TEM confirmed the presence of these viral proteins in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Representative images from 3 different patients are shown for illustration.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/13/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007143/2/m_advancesadv2022007143f4.png?Expires=1765951809&Signature=NpNH0xhrOs~6BG~M~spoPWeY3L~C9UWsCDRHyF4htDJsDDFCLs8m6~7WT69yVPR68-l9~mSX61fRvMqQIN0oNHxPv8l2rQIDQAAwMQauKNZhmNFFEhq-oz4YW5kS4y-uE1irQfA8Y4revtpPCiN1LY5akKP-Gbr-5hLEs1Ny4G00VLIBVszZPAVtVQHStOcgZoPMHNjkIa37eXp8te9M5l281PJfrSpTBD95U97war9GmxRx6EQDhmHcjplkctXpKPQnkEo9H8MMyy1dWRUfUOy99x5XChJfbut0nv2-4h9NJsLW7~YnGqi0UFgEZTUONkb6scqLLoYzmecuAUJOfw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Specific ultrastructural modifications in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. PRP from healthy donors (n = 6), septic patients without COVID-19 (bacterial sepsis, n = 4), and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) were fixed and analyzed by TEM (A). Representative electron micrographs at different magnification are shown. Different parameters and cellular elements were quantified using electron micrographs of platelet complete cross-sections (186 from n = 6 healthy donors [31 for each], 160 from n = 4 septic patients without COVID-19 [40 for each], and 240 from n = 10 patients with severe COVID-19 [24 for each]). The percentage of platelets exhibiting enlarged vesicles (vesicle surface/platelet cross section surface ratio > 6.1, which is the upper quartile for control platelets) was quantified (B). **P < .01; ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. To check whether the vesicle-like structures were part of the OCS, platelet-rich plsma from 4 healthy donors and 6 patients with severe COVID-19 was fixed and stained with tannic acid before analysis by TEM (C). Representative transmission electron micrographs are shown (the top two from healthy controls and the bottom ones from patients with COVID-19). Magnifications of selected areas (×10 000) show that the vesicles were not labeled with tannic acid, excluding their belonging to the OCS (see also supplemental Figure 11). The cross-sectional surface (D), the number of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (E), the surface of vesicle-like structures per cross-section (F), and the vesicle-like surface/platelet cross-section surface ratio (G) were quantified. ****P < .0001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence or absence of microtubules (H) and pseudopodia (I) per platelet cross-section was also quantified as parameters of platelet activation. Fischer’s test was used for statistical analysis.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/13/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007143/2/m_advancesadv2022007143f5.png?Expires=1765951809&Signature=NnIQxnm0Y-dScykV8rON5A79-Vulh5kMBRivffwLP2nX8DtSCymX3GW8CNg2SrinI7uXGVJrPKWJ8nTVli5HCyMkFv93qkI7Wxq6oJRZ7CZlJRqPKqlZZrSyb7qvqNPTQKAVmv3JWlPJSMRGya6dUJYAKQJ3eARr100KFTXuz25wqK6f1~xDUUn~kPP9WGsllSx20GPjMRNFIrAWrRlBrdEmDR36ikuCqXDewRatTTxnstsZKtT4l-tH6J-iQDIfthQO98Cn12nvEXUEHsnkkQ~oJSQaf72RJnLSe2VMF~lPU66wKxP03PopmgV-pVqzqdAXvAViT-~hU70StR2RnA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Presence of LC3B-positive vesicles in platelets from patients with severe COVID-19. Washed platelets from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) were fixed and labeled with a specific anti-LC3B antibody and analyzed by super-resolution confocal microscopy with the Airyscan module (A). F-actin staining using phalloidin-AF488 allowed platelet visualization. Representative images are shown (bar represents 1 µm). Images reconstructed in 3 dimensions (B) show LC3B spatial distribution in platelets of healthy control and patients with severe COVID-19. A representative western blotting analysis shows the level of LC3B-I and LC3B-II in platelets from 4 heathy donors (H1-H4) representative of 5 and from 4 patients with severe COVID-19 (P1-P4) representative of 7 (C, left panel). The exposure time was adjusted to efficiently distinguish the LC3BI and LC3BII forms. The quantification of the LC3B/actin ratio for LC3B-I and LC3B-II from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 7) is shown in the right panel. Results are mean ± SEM. **P < .01 ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Immunogold labeling of LC3B protein analyzed by TEM shows the number of gold particles by cross-section (30 from n = 3 healthy donors [10 for each] and 30 from n = 3 patients with severe COVID-19 [10 for each]) (D). Results are mean ± SEM. ***P < .001 according to the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The presence of LC3B associated with a large vacuole reminiscent of autophagosome (arrows and magnification insert) is shown in a platelet from patient with severe COVID-19 (E). Representative TEM sections of platelets from patients with severe COVID-19 (n = 10) showing structures typical of elongation membrane (EM), autophagosome (AP), and autophagolysosome-like (AL) (F).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/13/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007143/2/m_advancesadv2022007143f6.png?Expires=1765951809&Signature=VIzefk5-97kKNW9nZFpTjdFZ6HqnPSI~xzJ12WjfJOTZsdpn-ILXmIPswauakXQu16chNmX37a90B9NOQ1UosIAcETR3lIHyHshaQu5GFZsHY5aFgAgiPlNtQ78ZAxH6XcbL7IRJqITfFaO~rcMotbEFVZj1SCxOPyvoq847smm649552uLMfvRMFmdwKNEpd4~staOXgRGb8Ud5HTwYkkf0K~O4ewKyKB7WRRUzunUmNAzlSRftJHiFuj0jCXbhdMBu3-X3YMD-VpT6yA68Ui5SfBaIKePGPmkcnUGOQ2sK6uCrI-O-KkTUY~9GqnDMgedMh1RWB4NiyJFAxt3aow__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)