Key Points

Depletion of LNK (SH2B3) expands human HSCs that provide balanced multilineage reconstitution in xenotransplant.

Depletion of LNK (SH2B3) expands hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from FA patients in culture.

Abstract

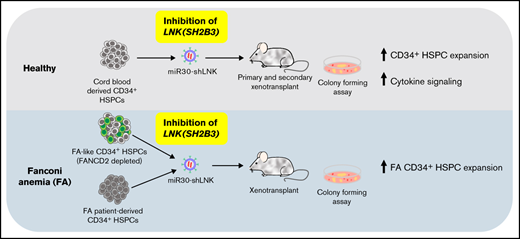

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only curative treatment for a variety of hematological diseases. Allogenic HSCT requires hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from matched donors and comes with cytotoxicity and mortality. Recent advances in genome modification of HSCs have demonstrated the possibility of using autologous HSCT-based gene therapy to alleviate hematologic symptoms in monogenic diseases, such as the inherited bone marrow failure (BMF) syndrome Fanconi anemia (FA). However, for FA and other BMF syndromes, insufficient HSC numbers with functional defects results in delayed hematopoietic recovery and increased risk of graft failure. We and others previously identified the adaptor protein LNK (SH2B3) as a critical negative regulator of murine HSC homeostasis. However, whether LNK controls human HSCs has not been studied. Here, we demonstrate that depletion of LNK via lentiviral expression of miR30-based short hairpin RNAs results in robust expansion of transplantable human HSCs that provided balanced multilineage reconstitution in primary and secondary mouse recipients. Importantly, LNK depletion enhances cytokine-mediated JAK/STAT activation in CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Moreover, we demonstrate that LNK depletion expands primary HSPCs associated with FA. In xenotransplant, engraftment of FANCD2-depleted FA-like HSCs was markedly improved by LNK inhibition. Finally, targeting LNK in primary bone marrow HSPCs from FA patients enhanced their colony forming potential in vitro. Together, these results demonstrate the potential of targeting LNK to expand HSCs to improve HSCT and HSCT-based gene therapy.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only curative treatment of both malignant and nonmalignant hematological diseases caused by underlying dysfunction in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Allogenic HSCT is an established treatment of such diseases; however, it requires a HLA-matched donor and comes with cytotoxicity and mortality.1-5 Cord blood (CB) offers an alternative donor source; however, low HSC numbers limit its use.6 Recent advances in lentiviral-based gene therapy that expresses an exogenous copy of the wild-type gene or delivery of programmable endonucleases (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats [CRISPR]/CRISPR-associated protein 9 [Cas9]) for genome editing of the endogenous locus in HSCs have demonstrated the potential of curing monogenic hematological disorders by autologous HSCT-based gene therapy.7-14 Autologous HSCT offers many advantages over allogenic HSCT for nonmalignant disorders, such as circumventing the requirement of finding a donor and reducing complications associated with myeloablative preconditioning.3,15 Although HSCT-based gene therapies are now clinically used for several disorders including sickle cell disease and β-Thalassemia,16,17 adenosine deaminase severe combined immunodeficiency,18 and others,14,19,20 this approach requires improved maintenance and/or expansion of HSCs for efficient reconstitution of gene-corrected HSCs for diseases which impair HSC function, such as bone marrow failure (BMF) syndromes.14,15,21 Despite the unmet need, few strategies have shown success in reliably expanding transplantable human HSCs. Therefore, additional therapeutic targets and deeper understanding of HSC expansion could improve HSCT.

The proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) is controlled by cytokine signaling. One such signaling pathway, thrombopoietin (TPO) binding to its cognate receptor MPL to activate tyrosine kinase JAK2, is essential to HSC self-renewal.21-23 A negative regulator of TPO/MPL and other cytokine signaling pathways in HSPCs is the adaptor protein LNK (SH2B3).24-30 LNK directly interacts with JAK2, and Lnk deficiency potentiates JAK2 activation and signaling in murine HSPCs.31 Consequently, Lnk−/− mice exhibit elevated blood counts and bone marrow (BM) progenitor numbers. Remarkably, Lnk deficiency in mice leads to an unprecedented ∼15-fold increase in HSC numbers with superior self-renewal ability without premature exhaustion.31-34 In humans, single nucleotide polymorphisms in LNK have been associated with increased blood counts and hemoglobin levels.35-39 A previous report showed that LNK deficiency increased the yield of erythroid cells differentiated from human pluripotent stem cell–derived hematopoietic progenitors in vitro.35 However, to date, no studies have investigated the potential of targeting LNK to expand human HSCs for transplantation in vivo.

Moreover, we recently showed in a mouse model (Fancd2−/−) of the inherited BMF syndrome Fanconi anemia (FA) that Lnk deficiency restores HSC numbers and functional defects.40 However, it remains to be determined if LNK deficiency expands and improves the function of primary HSCs from FA patients. FA is one of the most common BMF syndromes caused by mutations in any of the 22 FA genes responsible for DNA repair, DNA replication, and genome integrity.41,42 HSCT-based gene therapies show promise for curing FA15 ; however, efficacy of such approaches is impaired by limited numbers of patient HSCs,43 compromised growth in culture, and insufficient genetic modification resulting in low engraftment and suboptimal restoration of blood production post-HSCT.15 Therefore, strategies to expand FA HSCs could greatly improve therapeutic outcomes.

In this study, we inhibited LNK expression in CB-derived CD34+ HSPCs using lentiviral miR30-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). Xenotransplantation of LNK-depleted CB HSPCs robustly increased reconstitution of all hematopoietic lineages as well as HSPCs that are sustained in secondary transplants. Moreover, engraftment defects of FA-like (FANCD2-depleted) HSPCs were restored by LNK inhibition. Finally, targeting LNK in BM HSPCs from FA patients enhanced their colony forming potential in vitro. To our knowledge, this is the first strategy that promotes expansion of both primary FA HSCs and healthy HSCs. Together, these findings demonstrate the potential of targeting LNK to augment HSCT-based gene therapy for FA and potentially other hematological disorders.

Methods

CD34+ HSPC isolation, culture, and transduction

Fresh or cryopreserved, deidentified, umbilical CB were obtained from the New York Blood Center. Mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep, SepMate-50 tubes, Stemcell Technologies). CB or BM CD34+ HSPCs were isolated by magnetic separation on an AutoMACS Pro using microbeads conjugated with anti-human CD34 antibodies (Miltenyi). CD34+ HSPCs were cultured in StemSpan SFEM II (Stemcell Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 μM SR-1 (Stemcell Technologies), 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 40 ng/mL Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L), 50 ng/mL thrombopoietin (TPO), 20 ng/mL Interleukin-3 (IL3), 20 ng/mL Interleukin-6 (IL6), and 15 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Peprotech Inc. and Stemcell Technologies). For single transduction studies, after overnight culture, HSPCs were seeded onto plates coated in retronectin (Takara Bio) loaded with viral particles and spinoculated at 800xg at 37°C for 90 minutes. For sequential transduction studies, second lentiviral transduction was performed a day later. After spinoculation, HSPCs were cultured for an additional 16 to 20 hours and then collected for xenotransplantation. All transductions were conducted at a multiplicity of infection of 20 to 60 in the presence of Lentiblast (Oz Biosciences) supplemented in culture media.

CD34+ HSPC xenotransplantation

NOD.Cg-KitW-41JTyr+PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/ThomJ (NBSGW) mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratory (stock #026622)44 and expanded in our barrier facility. Six- to 8-week-old nonirradiated NBSGW mice were retro-orbitally infused with HSPCs 16 to 20 hours posttransduction. For single transduction studies (including FA patient HSPCs), 2x105 CD34+ HSPCs were infused per mouse, and for sequential transduction studies, 4x105 CD34+ HSPCs were infused per mouse. Human engraftment in the peripheral blood (PB) was tracked by retro-orbital blood collection and analyzed by flow cytometry. After 16 to 27 weeks, the BMs and spleens were isolated for flow cytometric analysis, and secondary xenotransplantation was conducted by infusing 107 total BM cells from primary recipients into NBSGW recipients.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide; 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), xenotransplantation, and colony forming unit (CFU) assays were analyzed for significance by 1- or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s, Tukey’s, or Šídáks multiple comparisons or by 2-tailed Student t tests as indicated in figure legends. Data pooled from multiple replicates are presented as mean plus or minus standard error of the mean (SEM). Representative technical replicate experiments are shown as mean plus or minus standard deviation (SD). The percent mCherry+ over time in the PB of xenografted mice was analyzed by simple linear regression analysis conducted in PRISM software using a general linear f test. For all statistical analysis, a P-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval

BM aspirate samples from healthy individuals and FA patients were obtained from the Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome Repository Study (Institutional Review Board #10-007569) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Biorepository samples used had been obtained as part of routine biobanking from previously enrolled subjects and from whom informed consent to participate in this repository study was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from all study participants or their legal guardians. All animal experiments for this work are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia under protocol #18-000781.

Results

Depletion of LNK in cord blood HSCs enhances peripheral blood engraftment in vivo

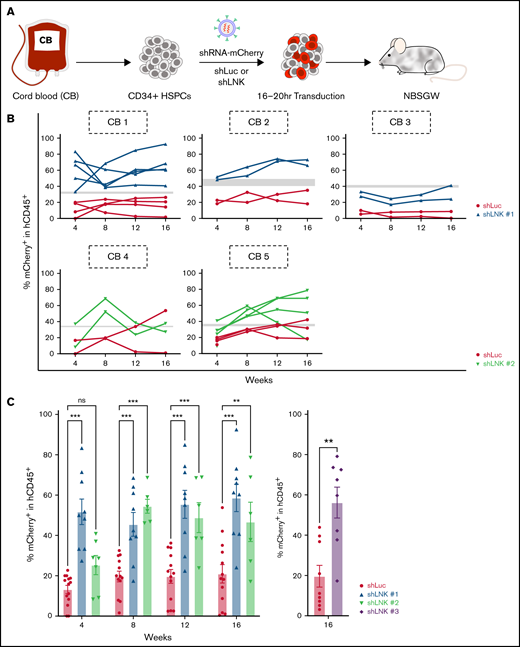

To investigate the potential of LNK inhibition in human HSPCs, we isolated CD34+ HSPCs from umbilical CB and transduced them with lentiviral miR30-based shRNAs that express mCherry as a fluorescent marker.45 HSPCs were transduced with control nontargeting shRNA to luciferase (Luc) or shRNAs that efficiently target expression of LNK and promoted TF1 cell growth (supplemental Figure 1). After 16 to 20 hours transduction, HSPCs were infused into NBSGW mice, which support human HSPC engraftment without preconditioning44 (Figure 1A). The mCherry+ transduction rates in culture at 48 hours were comparable between shRNAs to Luc and LNK in all experiments (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 2A). Using flow cytometry, we tracked human chimerism (hCD45+) and mCherry+ percentages in the PB every 4 weeks for 16 weeks and evaluated engraftment in the BM and spleen of xenotransplanted mice at 16 to 27 weeks.

LNK depletion enhances engraftment of umbilical CB HSCs in PB of xenotransplanted mice. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction and xenotransplantation assay. Primary human CD34+ HSPCs were isolated from CB and transduced with lentivirus expressing miR30-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to either Luc or LNK and coexpress mCherry as a fluorescent marker. Subsequently, transduced HSPCs were transplanted into immunodeficient NBSGW mice. (B) mCherry+ percentages in the hCD45+ PB of transplanted mice were examined every 4 weeks, up to 16 weeks, and percent mCherry+ within hCD45+ of individual mice in the PB over time is shown, represented by each solid line. Gray bars indicate the range of shLuc and shLNK mCherry+ transduction rates at time of transplant. Each graph tracks the reconstitution of an individual CB. (C) Mean percent mCherry+ within hCD45+ PB cells at different time points posttransplant is shown. Each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (shLuc vs shLNK #1 and #2) or 2-tailed Student t test (shLuc vs shLNK #3). N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 CBs for shLNK #1, 2 CBs for shLNK #2, and 3 CBs for shLNK #3. Ns, not significant

LNK depletion enhances engraftment of umbilical CB HSCs in PB of xenotransplanted mice. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction and xenotransplantation assay. Primary human CD34+ HSPCs were isolated from CB and transduced with lentivirus expressing miR30-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to either Luc or LNK and coexpress mCherry as a fluorescent marker. Subsequently, transduced HSPCs were transplanted into immunodeficient NBSGW mice. (B) mCherry+ percentages in the hCD45+ PB of transplanted mice were examined every 4 weeks, up to 16 weeks, and percent mCherry+ within hCD45+ of individual mice in the PB over time is shown, represented by each solid line. Gray bars indicate the range of shLuc and shLNK mCherry+ transduction rates at time of transplant. Each graph tracks the reconstitution of an individual CB. (C) Mean percent mCherry+ within hCD45+ PB cells at different time points posttransplant is shown. Each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (shLuc vs shLNK #1 and #2) or 2-tailed Student t test (shLuc vs shLNK #3). N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 CBs for shLNK #1, 2 CBs for shLNK #2, and 3 CBs for shLNK #3. Ns, not significant

CD34+ cells from single CB units were used for xenotransplantation in each experiment, then data were pooled from 8 CB units from 8 independent experiments. HSPCs transduced with shRNA to Luc (shLuc) or 3 independent shRNAs to LNK (shLNK) all efficiently engrafted NBSGW mice, similarly to nontransduced controls (supplemental Figure 2B). Total percent hCD45+ in the transplant mice were similar across all CBs with different shRNAs, achieving high levels of human chimerism in the PB, BM, and spleen, except 1 poorly engrafted CB (supplemental Figure 2C). The lineage distributions among the transplants of different CBs are comparable but with some variations (supplemental Figure 2D). We examined the percent mCherry+ in hCD45+ cells in the PB over time in 5 CB transplants and found that LNK depletion conferred superior reconstitution to the Luc controls in nearly every individual transplanted mouse recipient (Figure 1B). For the remainder 3 CB transplants, we were not able to collect PB monthly for analysis due to COVID-19 shutdown, thus only 16-week data are shown. Recipients of LNK-targeted HSPCs exhibited significantly elevated percent mCherry+ in comparison with Luc controls at each time point (Figure 1C). Importantly, at 16 weeks, all 3 shRNAs targeting LNK demonstrated elevated percent mCherry+ in hCD45+ PB compared with controls (Figure 1C). Simple linear regression analysis showed no significant trends of percent mCherry+ in hCD45+ cells over 4 to 16 weeks in the PB, indicating that shLuc-transduced HSPCs exhibit no toxicity and that shLNK-transduced HSPCs show expansion as early as 4 weeks in transplant (supplemental Figure 2E). These results suggest that LNK depletion enhances engraftment and blood reconstitution of healthy human HSCs.

LNK depletion in CB HSCs increases reconstitution of all hematopoietic lineages

Sixteen to 27 weeks posttransplantation, we analyzed human cell engraftment in the BMs and spleens of the recipient mice. We found LNK depletion increased the overall percent mCherry+ in both BM and spleen hCD45+ cells (Figure 2A). We analyzed the reconstitution of lymphoid (CD3+ T and CD19+ B cells), myeloid (CD33+SSChi granulocytes and CD33+SSClo monocytes), erythroid (CD235a+), and megakaryocytic (CD41a+) lineages by flow cytometry (Figure 2B-C). Recipients of LNK-depleted HSPCs exhibited significantly increased percent mCherry+ in all lineages compared with controls in the BM (Figure 2D) and the spleen (supplemental Figure 3A). We observed comparable hCD45+mCherry+ lineage distributions between Luc and LNK shRNAs in the BM (Figure 2E) and the spleen (supplemental Figure 3B). The slight differences we observed in the lineage distribution among different shRNAs to LNK might be due to variations among different CBs (supplemental Figure 2D). Collectively, our data does not suggest that LNK depletion leads to lineage bias. Additionally, we analyzed the production of human red blood cells and platelets in the BM (Figure 2C,F-H), as NBSGW mice are superior in supporting human engraftment of differentiated red blood cells and platelets.44 We found significantly higher mCherry+ levels in both red blood cells and platelets of LNK-targeted recipients compared with Luc controls (Figure 2F,H). These data suggest that LNK depletion in CB HSCs increases the reconstitution of all hematopoietic lineages in vivo.

LNK inhibition increases CB HSC reconstitution of all hematopoietic lineages in the bone marrow and spleen. CB-derived CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with lentiviral shRNAs to Luc or LNK and transplanted into NBSGW mice as described in Figure 1. After 16 to 27 weeks, BMs and spleens from the recipient mice were analyzed for human cell engraftment. (A) Mean percent mCherry+ in hCD45+ BM and spleen cells. (B) Representative myeloid and lymphoid flow cytometric plots in xenotransplanted mice. T cells (T) = CD3+, B cells (B) = CD19+, granulocytes (Gran) = CD33+SSChi, and monocytes (Mono) = CD33+SSClo. (C) Representative erythroid and megakaryocyte flow cytometric plots in xenotransplanted mice. Erythroid progenitors (Ery) = hCD45+CD235a+, red blood cells (hRBC) = hCD45-CD235a+, and megakaryocytes (Mk) = hCD45+CD41a+. (D) Mean percent mCherry+ within each hematopoietic lineage of the engrafted hCD45+ cells in the BM as shown in panels B and C. (E) Lineage distribution of engrafted hCD45+mCherry+ cells in the BM. (F) Mean percent mCherry+ of hRBCs in the BM as shown in panel C. (G) Representative platelet flow cytometric plot for panel H. (H) Mean percent mCherry+ of human platelets (hPlts) (FSClohCD45−mCD45−hCD61+) in the BM. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 1- (panels F and H) or 2-way (panels A, D, and E) ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to shLuc. N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 for shLNK #1, 2 for shLNK #2, and 3 for shLNK #3.

LNK inhibition increases CB HSC reconstitution of all hematopoietic lineages in the bone marrow and spleen. CB-derived CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with lentiviral shRNAs to Luc or LNK and transplanted into NBSGW mice as described in Figure 1. After 16 to 27 weeks, BMs and spleens from the recipient mice were analyzed for human cell engraftment. (A) Mean percent mCherry+ in hCD45+ BM and spleen cells. (B) Representative myeloid and lymphoid flow cytometric plots in xenotransplanted mice. T cells (T) = CD3+, B cells (B) = CD19+, granulocytes (Gran) = CD33+SSChi, and monocytes (Mono) = CD33+SSClo. (C) Representative erythroid and megakaryocyte flow cytometric plots in xenotransplanted mice. Erythroid progenitors (Ery) = hCD45+CD235a+, red blood cells (hRBC) = hCD45-CD235a+, and megakaryocytes (Mk) = hCD45+CD41a+. (D) Mean percent mCherry+ within each hematopoietic lineage of the engrafted hCD45+ cells in the BM as shown in panels B and C. (E) Lineage distribution of engrafted hCD45+mCherry+ cells in the BM. (F) Mean percent mCherry+ of hRBCs in the BM as shown in panel C. (G) Representative platelet flow cytometric plot for panel H. (H) Mean percent mCherry+ of human platelets (hPlts) (FSClohCD45−mCD45−hCD61+) in the BM. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 1- (panels F and H) or 2-way (panels A, D, and E) ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to shLuc. N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 for shLNK #1, 2 for shLNK #2, and 3 for shLNK #3.

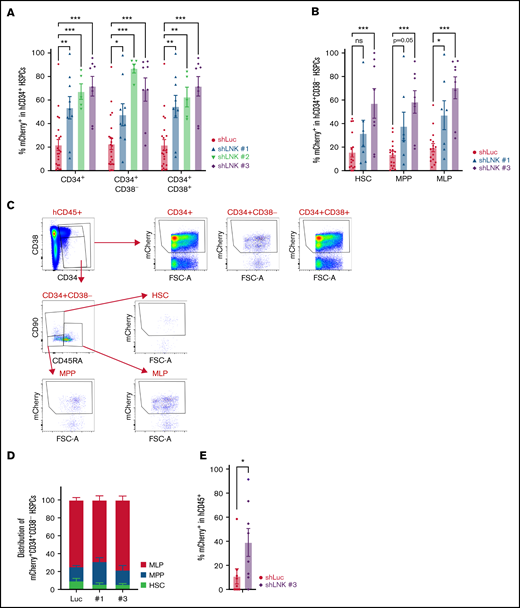

LNK depletion expands transplantable human HSCs in vivo

Increased hematopoietic reconstitution in LNK-depleted transplants prompted us to examine the CD34+ HSPC compartment. In the BM of transplanted mice, our data revealed marked expansion of all HSPC subpopulations, including HSCs (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+), multipotent progenitors (MPPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90−) and multilymphoid progenitors (MLPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA+CD90lo/−) in LNK-targeted recipients in comparison with that of Luc controls (Figure 3A-C). Moreover, we observed elevated mCherry+ levels in both the primitive CD34+CD38− and committed CD34+CD38+ HSPCs in the spleen (supplemental Figure 3C). Furthermore, the HSPC compartment of LNK-depleted recipients showed similar composition of CD34+CD38− subpopulations to that of controls, indicating LNK depletion results in the expansion of all HSPC compartments (Figure 3D). Finally, we performed secondary transplantation of total BM from primary recipients. Notably, we observed higher percent mCherry+ in LNK-targeted secondary recipients than Luc controls (Figure 3E). Collectively, these data suggest that LNK inhibition expands transplantable human HSCs in vivo.

Abrogation of LNK enhances the engraftment of transplantable HSCs in the bone marrow. CB-derived CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with lentiviral shRNAs to Luc or LNK and transplanted into NBSGW mice as described in Figure 1. (A) Mean percent mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+ compartment in the BM. (B) Mean percent mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+CD38− compartments in the BM HSCs (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+), multipotent progenitors (MPPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90−), and multilymphoid progenitors (MLPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA+CD90lo/−). (C) Representative HSPC flow cytometric analysis of the transplanted BM. (D) Proportion of HSPC subpopulations in the mCherry+CD34+CD38− compartment of engrafted BM. N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 CBs for shLNK #1, 2 CBs for shLNK #2, and 3 CBs for shLNK #3. (E) After 16 to 27 weeks, total BMs from shLuc and shLNK #3 primary recipients were transplanted into secondary NBSGW recipients. Mean mCherry+ percent in hCD45+ PB at week 12 is shown. N = 9 shLuc, n = 8 shLNK #3 mice. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to shLuc. Secondary xenotransplantation was analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test.

Abrogation of LNK enhances the engraftment of transplantable HSCs in the bone marrow. CB-derived CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with lentiviral shRNAs to Luc or LNK and transplanted into NBSGW mice as described in Figure 1. (A) Mean percent mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+ compartment in the BM. (B) Mean percent mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+CD38− compartments in the BM HSCs (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+), multipotent progenitors (MPPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90−), and multilymphoid progenitors (MLPs) (CD34+CD38−CD45RA+CD90lo/−). (C) Representative HSPC flow cytometric analysis of the transplanted BM. (D) Proportion of HSPC subpopulations in the mCherry+CD34+CD38− compartment of engrafted BM. N = 23 shLuc, n = 9 shLNK #1, n = 7 shLNK #2, and n = 8 shLNK #3 transplanted mice. The data are pooled from biological replicates n = 8 CBs for shLuc, 3 CBs for shLNK #1, 2 CBs for shLNK #2, and 3 CBs for shLNK #3. (E) After 16 to 27 weeks, total BMs from shLuc and shLNK #3 primary recipients were transplanted into secondary NBSGW recipients. Mean mCherry+ percent in hCD45+ PB at week 12 is shown. N = 9 shLuc, n = 8 shLNK #3 mice. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to shLuc. Secondary xenotransplantation was analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test.

LNK deficiency augments cytokine-mediated JAK/STAT signaling in human HSPCs

Lnk deficiency in mice enhances JAK/STAT signaling in HSPCs.24,28,31 We thus examined signal transduction impacted by LNK in primary human HSPCs. CB CD34+ HSPCs transduced with shRNAs to Luc or LNK were purified through flow cytometric sorting, then either directly plated for in vitro colony forming cell (CFC) assay or cultured for an additional 5 days and then plated for CFC (Figure 4A-B). We found that LNK depletion increased the number of CFU progenitors after transduction as well as after extended ex vivo culture (Figure 4A-B). Next, we investigated the mechanism behind the in vivo and in vitro proliferative advantage of LNK-depleted human HSPCs by assessing cytokine-mediated signaling. Purified HSPCs were starved and stimulated with different concentrations of GM-CSF. We found that reducing LNK protein level markedly increased STAT5 activation (Figure 4C-D). Thus, our findings suggest that LNK inhibition enhances primary human HSPC function and expansion by augmenting cytokine-mediated JAK/STAT signaling.

LNK depletion enhances colony forming potential and cytokine-induced STAT5 signaling in CD34+ HSPCs. CB-derived HSPCs were transduced with shRNAs to Luc or LNK and sorted for mCherry+ cells 48 hours posttransduction. (A-B) mCherry+ cells were either directly plated in methylcellulose (day 3) or cultured in cytokine-containing media for an additional 5 days (day 8) and subsequently plated in methylcellulose for CFC assay. CFU progenitor frequency was quantified after 12 to 14 days. (A) Representative CFU counts are shown per 500 CD34+ HSPCs. (B) Distribution of different types of colonies is shown. N = 3 CBs. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Šídák’s multiple comparisons. Representative colonies and full CFU plates are shown. (C) Purified mCherry+ CD34+ HSPCs were starved for 2 hours and stimulated with different concentrations of GM-CSF for 10 minutes. Cells were lysed and subjected to western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. Representative blots for cytokine-induced JAK/STAT activation are shown. Protein levels were quantified by the intensity of the bands then normalized to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) controls, and the numbers are shown underneath the respective protein band. (D) Relative protein levels of LNK and phosphorylated proteins of individual CB samples after stimulation with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF is shown. N = 3 CBs. Each colored symbol and dashed line indicate an individual CB sample in each independent experiment. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, calculated using paired 2-tailed Student t tests. GEMM, granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, megakaryocyte CFUs.

LNK depletion enhances colony forming potential and cytokine-induced STAT5 signaling in CD34+ HSPCs. CB-derived HSPCs were transduced with shRNAs to Luc or LNK and sorted for mCherry+ cells 48 hours posttransduction. (A-B) mCherry+ cells were either directly plated in methylcellulose (day 3) or cultured in cytokine-containing media for an additional 5 days (day 8) and subsequently plated in methylcellulose for CFC assay. CFU progenitor frequency was quantified after 12 to 14 days. (A) Representative CFU counts are shown per 500 CD34+ HSPCs. (B) Distribution of different types of colonies is shown. N = 3 CBs. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Šídák’s multiple comparisons. Representative colonies and full CFU plates are shown. (C) Purified mCherry+ CD34+ HSPCs were starved for 2 hours and stimulated with different concentrations of GM-CSF for 10 minutes. Cells were lysed and subjected to western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. Representative blots for cytokine-induced JAK/STAT activation are shown. Protein levels were quantified by the intensity of the bands then normalized to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) controls, and the numbers are shown underneath the respective protein band. (D) Relative protein levels of LNK and phosphorylated proteins of individual CB samples after stimulation with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF is shown. N = 3 CBs. Each colored symbol and dashed line indicate an individual CB sample in each independent experiment. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, calculated using paired 2-tailed Student t tests. GEMM, granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, megakaryocyte CFUs.

Inhibition of LNK ameliorates HSC engraftment defects associated with FA

Our results so far suggest that LNK inhibition may be a viable strategy to promote the expansion of healthy HSPCs by augmenting cytokine signaling. Next, we wanted to determine if LNK inhibition could promote the expansion of HSPCs from BMF syndromes with compromised growth ability. Our previous studies indicated that Lnk deficiency restores the function of HSCs in Fancd2−/− mouse models.40 Therefore, we set out to test if LNK depletion would enhance expansion of human FA HSPCs. Due to the paucity of sufficient numbers of patient-derived HSPCs for xenotransplantation, we started out by establishing FA-like HSPCs as previously described.43 CD34+ cells from single CB units were used for xenotransplantation in each experiment, then data were pooled from 4 CB units from 4 independent experiments. We first transduced CD34+ HSPCs with a lentiviral shRNA targeting Luc control or FANCD2, along with green florescent protein (GFP) as a marker, followed by transduction with lentiviral shRNA to Luc or LNK coexpressing mCherry. Subsequently, we infused unsorted double-transduced HSPCs into NBSGW mice (Figure 5A), allowing us to directly compare how the FA-like HSPCs function with and without LNK inhibition between groups and in the same mouse. Importantly, the transduction rates were not significantly different between experimental groups at time of transplant (Figure 5D). Double lentiviral transduction and longer culture resulted in reduced overall human chimerism (hCD45+) in comparison with our single transduction studies, particularly in the PB, which had very low reconstitution rates overall (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 2B). Although the Luc/Luc and FANCD2/LNK groups showed comparable human chimerisms to those of nontransduced controls, FANCD2/Luc recipient mice displayed significantly lower reconstitution (Figure 5B). Moreover, recipients of FANCD2-depleted HSPCs exhibited markedly reduced hCD45+GFP+mCherry+ chimerism in the BM and spleens compared with the controls (Figure 5C). Importantly, LNK depletion in FA-like cells (FANCD2/LNK) significantly increased hCD45+GFP+mCherry+ chimerism in comparison with that of FANCD2/Luc, and in fact, it restored the reconstitution level to that of Luc/Luc control in all hematopoietic tissues (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 4). These data indicate that LNK depletion restores the reconstitution of FA-like HSPCs.

LNK depletion improves engraftment defects of FA-like HSCs in xenotransplant. (A) Experimental scheme of xenotransplantation assay. CB-derived CD34+ cells were first transduced with lentivirus-expressing GFP and either shLuc or shFANCD2 to establish FA-like HSPCs. Subsequently, the cells were transduced with lentivirus-expressing mCherry and either shLuc or shLNK #1 and transplanted into NBSGW recipients. The PB was analyzed every 4 weeks for 16 weeks, and after 16 to 22 weeks, the BMs and spleens were analyzed. (B) Total human chimerism (percent hCD45+) in xenotransplanted mice in the PB at 16 weeks, BM and spleen (Spl) is shown. * = P < .05, calculated using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to nontransduced control. (C) Mean percent hCD45+GFP+mCherry+ chimerism in the PB at 16 weeks; BM and Spl are shown. (D) Mean GFP/mCherry transduction rates at time of transplant from 4 different CBs are shown. (E) Chimerism of each transduced population (GFP+mCherry+, GFP+mCherry−, GFP-mCherry+, and GFP−mCherry−) in the BM or spleen are shown as stacked means (left panel). The right panel illustrates the predicted reduction or expansion of each transduced cell population upon FANCD2 or LNK depletion. (F) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ within each lineage of the engrafted hCD45+ cells in the BM (T cells [T] = CD3+, B cells [B] = CD19+, myeloid [Mye] = CD33+, erythroid progenitors [Ery] = CD235a+, megakaryocytes [Mk] = CD41a+). (G) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+ HSPC compartment in the BM. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. N = 12 shLuc/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLNK, and n = 5 for nontransduced transplanted mice. The data are pooled from 4 different biological replicate CBs.

LNK depletion improves engraftment defects of FA-like HSCs in xenotransplant. (A) Experimental scheme of xenotransplantation assay. CB-derived CD34+ cells were first transduced with lentivirus-expressing GFP and either shLuc or shFANCD2 to establish FA-like HSPCs. Subsequently, the cells were transduced with lentivirus-expressing mCherry and either shLuc or shLNK #1 and transplanted into NBSGW recipients. The PB was analyzed every 4 weeks for 16 weeks, and after 16 to 22 weeks, the BMs and spleens were analyzed. (B) Total human chimerism (percent hCD45+) in xenotransplanted mice in the PB at 16 weeks, BM and spleen (Spl) is shown. * = P < .05, calculated using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to nontransduced control. (C) Mean percent hCD45+GFP+mCherry+ chimerism in the PB at 16 weeks; BM and Spl are shown. (D) Mean GFP/mCherry transduction rates at time of transplant from 4 different CBs are shown. (E) Chimerism of each transduced population (GFP+mCherry+, GFP+mCherry−, GFP-mCherry+, and GFP−mCherry−) in the BM or spleen are shown as stacked means (left panel). The right panel illustrates the predicted reduction or expansion of each transduced cell population upon FANCD2 or LNK depletion. (F) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ within each lineage of the engrafted hCD45+ cells in the BM (T cells [T] = CD3+, B cells [B] = CD19+, myeloid [Mye] = CD33+, erythroid progenitors [Ery] = CD235a+, megakaryocytes [Mk] = CD41a+). (G) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+ HSPC compartment in the BM. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. N = 12 shLuc/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLNK, and n = 5 for nontransduced transplanted mice. The data are pooled from 4 different biological replicate CBs.

We reasoned that the proliferative advantage conferred by LNK inhibition in FA-like HSPCs (GFP+mCherry+) could be partially masked by the robust expansion of LNK-depleted cells in the control population (GFP-mCherry+) of the same mouse. Therefore, we examined the contribution of each transduced population impacted by FANCD2 or LNK depletion in recipient mice. As expected, the chimerism of each transduced population in control Luc/Luc mice was consistent with initial transduction rates at time of transplant (Figure 5D-E). FANCD2-depleted cell populations in the FANCD2/Luc (GFP+mCherry+ and GFP+mCherry-) and FANCD2/LNK (GFP+mCherry-) recipients contributed significantly less to human chimerism than Luc controls. In contrast, LNK depletion markedly increased the proportions of both FA-like and normal-like populations in the FANCD2/LNK recipients (GFP+mCherry+ and GFP-mCherry+, respectively) (Figure 5E). Furthermore, LNK inhibition restored the reconstitution of hematopoietic lineages affected by FANCD2 deficiency (Figure 5F). More importantly, targeting LNK in FA-like HSPCs markedly increased the levels of the engrafted CD34+ HSPC compartment in the BM of recipients (Figure 5G). Taken together, these results suggest that depleting LNK in FA-like HSCs greatly improves their engraftment defects in xenotransplant.

LNK depletion expands FA patient-derived HSPCs

With the promising results of FA-like HSPC transplants, we tested the potential of LNK inhibition in primary BM CD34+ HSPCs isolated from FA patients. We purified FA patient HSPCs transduced with lentiviral shRNAs targeting LNK or Luc by flow cytometric sorting, then performed CFC assay (Figure 6A). We found LNK depletion increased CFU progenitor potentials of all 6 FA patients tested, including 3 FANCA, 1 FANCC, and 2 FANCD1 (BRCA2) patients, as well as healthy BM controls (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 5A-B). In addition, we transplanted freshly-isolated HSPCs from 1 FANCD1 patient into NBSGW mice. Despite low levels of total hCD45+ chimerism, LNK inhibition enhanced percent mCherry+ in the BM and spleen compared with control (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 5C). Hence, our results indicate that LNK depletion expands primary FA HSPCs in culture.

LNK inhibition expands primary patient-derived FA HSPCs. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction followed by CFC or xenotransplantation assay. Primary CD34+ HSPCs were isolated from BM aspirates of healthy individuals or FA patients and transduced with lentivirus-expressing shLuc or shLNK along with the mCherry marker. Transduced cells were either directly injected into NBSGW mice or plated for CFC assays after flow cytometric sorting of mCherry+ cells. (B) Healthy or FA HSPCs were sorted for mCherry positivity 48 hours posttransduction and plated onto semisolid methylcellulose culture media. CFU progenitors were enumerated 12 to 14 days later. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-tailed Student t tests. N = 2 healthy samples and 6 FA patient samples. (C) Transduced HSPCs from a FA patient (FA-D1 #600.01) were transplanted into NBSGW mice, and engraftment in the BM and spleen was assessed after 16 weeks. Percent mCherry+ in the engrafted hCD45+ BM and spleen is shown. N = 1 patient FA-D1 #600.01, 1 mouse per shRNA. Bars indicate percent mCherry+.

LNK inhibition expands primary patient-derived FA HSPCs. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction followed by CFC or xenotransplantation assay. Primary CD34+ HSPCs were isolated from BM aspirates of healthy individuals or FA patients and transduced with lentivirus-expressing shLuc or shLNK along with the mCherry marker. Transduced cells were either directly injected into NBSGW mice or plated for CFC assays after flow cytometric sorting of mCherry+ cells. (B) Healthy or FA HSPCs were sorted for mCherry positivity 48 hours posttransduction and plated onto semisolid methylcellulose culture media. CFU progenitors were enumerated 12 to 14 days later. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-tailed Student t tests. N = 2 healthy samples and 6 FA patient samples. (C) Transduced HSPCs from a FA patient (FA-D1 #600.01) were transplanted into NBSGW mice, and engraftment in the BM and spleen was assessed after 16 weeks. Percent mCherry+ in the engrafted hCD45+ BM and spleen is shown. N = 1 patient FA-D1 #600.01, 1 mouse per shRNA. Bars indicate percent mCherry+.

LNK depletion promotes the growth of FA-like HSPCs in the presence of DNA stressors

Given our positive results demonstrating the expansion of FA-like and primary FA patient HSPCs by targeting LNK in vitro and in vivo, we wanted to assess the response to genotoxic and replication stress. FA cells are unable to repair interstrand crosslink DNA damage (ICL)46-49 and are hypersensitive to replication stress.50-52 Previously, in FA mouse models, we demonstrated that Lnk deficiency ameliorated replication stress by stabilizing replication forks but did not rescue sensitivity to ICLs.40 Here, using our FA-like cells, we performed survival CFC assays with ICL-inducing agents mitomycin C (MMC) and acetaldehyde, as well as hydroxyurea (HU), to induce replication stress (Figure 7A). We found that although LNK depletion robustly enhanced the clonogenic growth of FA-like HSPCs (shRNA-FANCD2/LNK) in all conditions compared with Luc-depleted FA-like cells (shRNA-FANCD2/Luc) (Figure 7B), it did not significantly rescue the hypersensitivity to MMC or acetaldehyde associated with FA (Figure 7C-D). Of note, in our culture conditions, FA-like cells did not show hypersensitivity to HU, and LNK depletion did not affect HU sensitivity (Figure 7E). Collectively, this data suggests that LNK depletion promotes the growth of FA-like cells in the presence or absence of various stressors, although it does not restore the ability to resolve ICLs.

LNK inhibition enhances clonogenic potential of FA-like HSPCs in the presence of various DNA stressors. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction followed by CFC. CB-derived CD34+ cells were first transduced with lentivirus-expressing GFP and either shLuc or shFANCD2 to establish FA-like HSPCs. Subsequently, the cells were transduced with lentivirus-expressing mCherry and either shLuc or shLNK #1, and 48 hours post–second transduction, GFP+mCherry+ cells were sorted and either directly plated in methylcellulose CFC assay with indicated concentrations of MMC or HU or were pretreated for 4 hours with acetaldehyde (Ace) and then plated in methylcellulose. Vehicle-treated cells were used as control. (B) CFU numbers were quantified after 12 to 14 days and a representative experiment is shown. (C-E) Percentages of CFUs in indicated drugs relative to vehicle-treated controls are shown. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. For simplicity, in panels C-E, multiple comparisons for shLuc/shLNK are not shown.

LNK inhibition enhances clonogenic potential of FA-like HSPCs in the presence of various DNA stressors. (A) Experimental scheme of lentiviral transduction followed by CFC. CB-derived CD34+ cells were first transduced with lentivirus-expressing GFP and either shLuc or shFANCD2 to establish FA-like HSPCs. Subsequently, the cells were transduced with lentivirus-expressing mCherry and either shLuc or shLNK #1, and 48 hours post–second transduction, GFP+mCherry+ cells were sorted and either directly plated in methylcellulose CFC assay with indicated concentrations of MMC or HU or were pretreated for 4 hours with acetaldehyde (Ace) and then plated in methylcellulose. Vehicle-treated cells were used as control. (B) CFU numbers were quantified after 12 to 14 days and a representative experiment is shown. (C-E) Percentages of CFUs in indicated drugs relative to vehicle-treated controls are shown. Each symbol represents an individual plate; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. For simplicity, in panels C-E, multiple comparisons for shLuc/shLNK are not shown.

Discussion

Recent advances in lentiviral gene transfer and delivery of programmable endonucleases for genome editing in HSCs for HSCT have demonstrated potential to cure inherited hematologic disorders7-15 and are increasingly used clinically for some diseases.16-20 However, these approaches are limited by our inability to reliably expand transplantable human HSCs, particularly for disorders with HSC defects such as FA and other BMF syndromes. This study highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting LNK in human HSPCs to augment their growth and enhance engraftment in HSCT.

We demonstrated improved function and robust expansion in xenotransplant of CD34+ HSPCs upon inhibition of LNK expression with 3 independent miR30-based shRNAs in 8 CB samples. LNK depletion in CD34+ HSPCs resulted in robust expansion across all hematopoietic lineages, including increased production of mature human red blood cells and platelets in addition to myeloid and lymphoid lineages. Importantly, LNK depletion resulted in marked expansion of each subpopulation of the engrafted CD34+ HSPC compartment, including HSCs with enhanced repopulating capacity in secondary transplant. Collectively, our data demonstrate robust expansion of CB HSCs upon LNK depletion.

We show that reducing LNK protein level augments cytokine-induced JAK/STAT signaling in human CD34+ HSPCs. These data provide the first experimental evidence that LNK regulates cytokine signaling in primary human HSPCs and highlight the importance of these pathways in human HSPC function. Moreover, these data demonstrate that reducing LNK protein level, rather than genetic ablation, is sufficient to promote robust expansion of CD34+ HSPCs. Thus, deeper molecular investigations into how LNK controls the expansion of CD34+ HSPCs via cytokine signaling and/or additional pathways could improve our understanding of the signaling pathways essential to human HSC expansion.

To determine if LNK depletion could expand disease HSPCs, we turned to FA as autologous HSCT-based gene therapy has demonstrated some success in ameliorating BMF.15 We used an established model of transplanting FANCD2-depleted FA-like HSPCs43 and, indeed, found that LNK depletion fully restored the transplant defects associated with FA. Our findings showed that LNK-targeted FA-like HSCs expanded and outcompeted nontargeted FA-like HSCs, suggesting its future therapeutic potential in boosting gene therapy for FA. Furthermore, we investigated this directly in primary HSPCs from FA patients. We found that LNK depletion consistently enhanced the in vitro clonogenic potential of HSPCs harboring mutations in FANCA, FANCC, and FANCD1 (BRCA2). Although limited to a single patient xenotransplant, we demonstrated preliminary evidence that LNK depletion can enhance the in vivo expansion of primary FA HSCs.

Our findings have direct implications for improving autologous gene therapy HSCTs for FA. The success of the FANCOLEN-1 clinical trial demonstrated long-term engraftment of lentiviral FANCA-corrected HSCs for the first time in patients, resulting in BMF stabilization.15 However, engraftment and expansion of FANCA-corrected HSCs was slow, resulting in suboptimal restoration of blood counts in some patients. This trial revealed that patients infused with greater numbers of HSPCs exhibited more robust recovery and showed a strong correlation between the frequency of FANCA-corrected CD34+ HSPCs in the BM and phenotypic improvement of FA symptoms.15 Importantly, LNK depletion in FA-like HSPCs markedly improved engraftment levels of the CD34+ compartment. Therefore, our studies suggest for a genetic suppression strategy to enhance the curative potential of FA gene therapy with combined LNK depletion and restoration of functional FA genes. Furthermore, FA and other BMF patients often receive androgen therapy to increase blood counts and delay BMF while finding a matched donor for allogenic HSCT; however, there are significant side effects.53,54 Therefore, developing a strategy to inhibit LNK in these patients could be a safer alternative to androgen therapy.

Recent work has shown that FA HSPCs exist in dichotomous states with either high levels of TP53 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) growth suppressive signaling or MYC pathway activation to counteract this growth suppression.55 In FA HSPCs, genetic suppression of TP53 improves expansion but could exacerbate genome instability and tumorigenesis, whereas pharmacological inhibition of MYC limits HSPC expansion.43,55,56 In contrast, TGF-β inhibition improves FA HSPC function by increasing homologous recombination.57 It has been shown that Lnk deficiency in murine HSPCs improves replication fork stability40 ; however, it remains to be determined if LNK inhibition ameliorates replication stress in primary human HSPCs. Although inhibition of hyperactivated TP53, MYC, and TGF-β pathways can improve FA HSPCs, their potential for healthy HSPC expansion is unclear. Therefore, this work demonstrates that targeting LNK can be an additive effect to augment FA HSC expansion in addition to genetic correction and is a rare and novel strategy to expand both healthy and diseased HSCs, underscoring the broad importance of LNK-regulated cytokine signaling in human HSC function.

To that end, it is imperative that we target LNK in a therapeutically safe way as dysregulated cytokine signaling can contribute to development of hematological malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemias and myeloproliferative neoplasms.58-60 Although there are no reports of LNK mutations alone driving hematological malignancies and very limited reports of clonal hematopoiesis in humans,61 aged Lnk−/− mice do develop myeloproliferative neoplasm–like diseases.34 For these reasons, we chose not to use CRISPR to permanently delete LNK in human HSPCs, and, encouragingly, we did not observe evidence of lineage bias or oncogenic transformation in our xenotransplant models upon constitutive inhibition of LNK expression by lentiviral shRNA. Our data suggest that reducing the protein level of LNK in human HSCs is sufficient to improve expansion, and, therefore, strategies to inducibly or transiently target LNK in human HSCs warrant further investigation.

In summary, our results strongly support the further investigation of LNK inhibition as a strategy to expand gene-corrected HSCs in gene therapy HSCT for FA and potentially other BMF syndromes. Further investigations will focus on safer, tunable means of LNK inhibition and seek to elucidate the molecular consequences of augmented cytokine signaling.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Flow Cytometry and Biorepository Core Facilities, as well as the Department of Veterinary Resources of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for their support. They thank Shannon McKinney-Freeman, Raphael Ceccaldi, and Jean Soulier for providing the lentiviral vectors used in this study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL095675 and R01HL133828 (W.T.); awards from Fanconi Anemia Research Fund and the Basser Center for BRCA Team Science grant (W.T.); NIH grants F31HL139091-01 and T32HL007971-15 (N.H.); and grants from Hyundai Hope on Wheels and the Cure Childhood Cancer Foundation, as well as the Department of Defense Bone Marrow Failure Research Program Idea Development Awards (T.S.O. and W.T.), one of which supports the repository. This work is in part funded under a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (W.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: N.H. and W.T. designed experiments, interpreted results, and prepared this manuscript; N.H., G.L., V.C., and C.S.S. performed experiments; and P.N. and T.S.O. provided Fanconi anemia patient samples and reviewed this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wei Tong, Abramson Bldg. 310D, 3615 Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: tongw@chop.edu.

References

Author notes

W.T. is the lead author.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Wei Tong (tongw@chop.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![LNK depletion improves engraftment defects of FA-like HSCs in xenotransplant. (A) Experimental scheme of xenotransplantation assay. CB-derived CD34+ cells were first transduced with lentivirus-expressing GFP and either shLuc or shFANCD2 to establish FA-like HSPCs. Subsequently, the cells were transduced with lentivirus-expressing mCherry and either shLuc or shLNK #1 and transplanted into NBSGW recipients. The PB was analyzed every 4 weeks for 16 weeks, and after 16 to 22 weeks, the BMs and spleens were analyzed. (B) Total human chimerism (percent hCD45+) in xenotransplanted mice in the PB at 16 weeks, BM and spleen (Spl) is shown. * = P < .05, calculated using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to nontransduced control. (C) Mean percent hCD45+GFP+mCherry+ chimerism in the PB at 16 weeks; BM and Spl are shown. (D) Mean GFP/mCherry transduction rates at time of transplant from 4 different CBs are shown. (E) Chimerism of each transduced population (GFP+mCherry+, GFP+mCherry−, GFP-mCherry+, and GFP−mCherry−) in the BM or spleen are shown as stacked means (left panel). The right panel illustrates the predicted reduction or expansion of each transduced cell population upon FANCD2 or LNK depletion. (F) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ within each lineage of the engrafted hCD45+ cells in the BM (T cells [T] = CD3+, B cells [B] = CD19+, myeloid [Mye] = CD33+, erythroid progenitors [Ery] = CD235a+, megakaryocytes [Mk] = CD41a+). (G) Mean percent GFP+mCherry+ in the engrafted CD34+ HSPC compartment in the BM. In all relevant panels, each symbol represents an individual mouse; bars indicate mean values; error bars indicate plus or minus SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 as determined by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. N = 12 shLuc/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLuc, n = 15 shFANCD2/shLNK, and n = 5 for nontransduced transplanted mice. The data are pooled from 4 different biological replicate CBs.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/3/10.1182_bloodadvances.2021004205/3/m_advancesadv2021004205f5.png?Expires=1767705087&Signature=uxthuZqoJUPQ-MVg0FrB8xDOl2moJJx-NjR3RemfOOv16MZUuKH37YdaaY2oY83ay16d9OXlp38HOjehvEJoEq0wtisgiKTtXruEelA70Qgz2r1w8vd1tCCwDZWchFGg3ERkTO4y0kQuJDexlxYNJcCnhXrZVysgkLsnwTSdYZN-v2zkkmrHAT0A6UMwArTPEAfRbQ6Rvl~-GCXzUIgU~v-MSrNsu21xzthHpqCv5RFE0iNiU~0syl9GyHTkZO~VuG1hvMsitCYzymHBeIqmzEZTS~73H~M0~0-PrWlQ0fyex23Xp0XMVxwQxwoQS3G--YWsZJWuPmtEwWG0tNkI9Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)