Key Points

Breast tumor–produced coagulation FVII induces EMT and liver metastasis via endothelial protein C receptor.

Blood-borne FVII antagonizes the effects of tumor-expressed FVII by activating the TF-PAR2 axis.

Abstract

Cancer enhances the risk of venous thromboembolism, but a hypercoagulant microenvironment also promotes cancer progression. Although anticoagulants have been suggested as a potential anticancer treatment, clinical studies on the effect of such modalities on cancer progression have not yet been successful for unknown reasons. In normal physiology, complex formation between the subendothelial-expressed tissue factor (TF) and the blood-borne liver-derived factor VII (FVII) results in induction of the extrinsic coagulation cascade and intracellular signaling via protease-activated receptors (PARs). In cancer, TF is overexpressed and linked to poor prognosis. Here, we report that increased levels of FVII are also observed in breast cancer specimens and are associated with tumor progression and metastasis to the liver. In breast cancer cell lines, tumor-expressed FVII drives changes reminiscent of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor cell invasion, and expression of the prometastatic genes, SNAI2 and SOX9. In vivo, tumor-expressed FVII enhanced tumor growth and liver metastasis. Surprisingly, liver-derived FVII appeared to inhibit metastasis. Finally, tumor-expressed FVII-induced prometastatic gene expression independent of TF but required a functional endothelial protein C receptor, whereas recombinant activated FVII acting via the canonical TF:PAR2 pathway inhibited prometastatic gene expression. Here, we propose that tumor-expressed FVII and liver-derived FVII have opposing effects on EMT and metastasis.

Introduction

Increasing evidence points toward a role for a procoagulant microenvironment in cancer progression.1 Coagulation factors such as factor VII (FVII) and FX, produced by the liver and present in the circulation, are part of this tumor milieu and can bind the initiator of coagulation tissue factor (TF). TF is broadly expressed by cancer cells and is associated with a higher tumor grade and reduced survival in patients with cancer.1-3 Although in normal physiology, TF in complex with FVII and FX leads to thrombin production to form a blood clot after vascular damage, TF also functions as a cellular cofactor to induce FVII-dependent cleavage of the protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2).4 PAR2 activation leads to an inflammatory and angiogenic response that facilitates primary tumor growth.5,6

Numerous studies have shown that, apart from the liver, cancer cells can produce FVII.7-11 This is regulated via epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–,9 hypoxia-,12 or androgen receptor–mediated pathways.13 Tumor-expressed FVII induces procoagulant activity and regulates the invasion and migration of cancer cells, mainly via activation of PAR2.7 Nevertheless, the relation between FVII expression in tumors, clinicopathological parameters, and patient survival has hardly been investigated. Therefore, we investigated clinical and mechanistic links between tumor-expressed FVII and cancer progression in clinical samples, in vitro models, and mouse models. In addition, we investigated the relative contributions of tumor-expressed and liver-derived FVII on cancer progression.

Methods

Patient material

Analyses on clinical variables were performed on tumors from the breast cancer cohort described previously.2 Approval was obtained from the Leiden University Medical Center Medical Ethics Committee. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Tissue microarrays were stained for FVII and TF. Staining intensity was assessed by 2 independent observers and Cohen’s κ > 0.8. FVII positivity was defined as any staining vs no staining. TF positivity was defined as the second to fourth quartile (positive) vs first quartile (negative).

Cell culture and viral transductions

Cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Bodinco, Alkmaar, The Netherlands), l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). TF knockout MDAFVII, MDApcDNA, and control cells were created using TF-specific or control CRISPR lentivirus (Sigma-Aldrich).

Lentivirus was produced in HEK293T cells using lentiviral packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pCMV-VSV-G (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) and polyethylenimine reagent (PEI, Polysciences, Warrington, PA). For selective gene knockdowns, transductions were carried out using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) specific for FVII, endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR), PAR1, or PAR2 (Sigma Mission library, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by selection on 2 μg/mL puromycin.

Cell migration, invasion, and proliferation

Cells (3 × 104) mixed with 50 μg/mL mAb-3G12 or immunoglobulin G1 were seeded in the top compartment of Biocoat invasion (Matrigel-coated) or migration (no Matrigel) chambers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum was used in the lower compartment. After 16 hours, invasion and migration were quantified using crystal violet staining. Cell proliferation was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay, as described before.14

In vivo studies

Mouse experiments were approved by the Leiden University Medical Center Animal Welfare Committee. Six-week-old female NOD-Scid-gamma mice (Charles River, Ecully, France) were orthotopically grafted with 1 × 106 MDApcDNA or MDAFVII cells as described before.15 Experimental metastasis was induced by injecting 1 × 106 cells into the lateral tail vein. Liver-specific FVII knockdown was achieved by injecting Invivofectamine 2.0–complexed F7 or control short interfering RNA (siRNA) in the tail vein every 14 days, starting 1 day before grafting. Tail blood was collected to verify FVII levels. To test the effects of anticoagulants, mice were fed a custom-made chow diet as described before.16

The tumor size was measured using calipers and calculated as 0.5 x (length x width2). After the sacrifice, tumor, blood, lungs, and liver were collected. To assess metastasis in target organs, human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA (mRNA) was normalized to the expression of mouse β-actin.

mRNA analysis

For quantitative polymerase chain reaction, RNA was isolated using TRIsure (Bioline, London, United Kingdom) and converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using Super Script II (Life Technologies). Tissues were disrupted in TRIsure using an Ultra Turrax homogenizer (IKA, Staufen, Germany). Cells were treated with 40 mM LiCl, 10 nM recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa), 100 nM FXa (Enzyme Laboratories, Canterbury, Australia), 100 ng/mL Wnt3a or Wnt5a (RnD Systems, Oxford, United Kingdom), 10 μM PAR2 antagonist GB83 (Axon Medchem, Reston, VA), 10 μM PAR1 antagonist RWJ-56110 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom), 10 μM transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) receptor inhibitor SB43152, 10 μM EGFR inhibitor AG1478, 50 μg/mL EGF, 50 μg/mL mouse monoclonal anti-EPCR mAb-JRK1949, or 50 μg/mL mAb-3G12 for the indicated times. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed as described previously16 using primers listed in supplemental Table 1.

For microarray analysis, RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini (Qiagen) and biotin-labeled for hybridization on Illumina HumanHT-12-v4 BeadChips. Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org) was used for the analyses. The lumi library was loaded into R, and Loess normalization was applied. Finally, the Limma library was used for performing statistical comparisons between MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells. The top 200 upregulated and downregulated genes in MDAFVII cells were uploaded in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems) or Enrichr (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/).

Statistical analysis

Associations between FVII expression and metastasis were determined using Kaplan-Meier. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Statistics were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc). Unpaired 2-sided t test and 1-/ 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction were used as appropriate. Significance is indicated by asterisks (∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001).

Results

Tumor-expressed FVII in breast cancer is associated unfavorably with survival

We assessed FVII protein expression in a cohort of 574 patients with breast cancer, which has been described previously.17 Immunohistochemical analysis was performed only for patients who had not received systemic therapy (n = 369). Expression of FVII by tumor cells was observed in 39% (130/331) of the cases but not in healthy tissue (Figure 1A). Analysis of F7 mRNA expression in a selection of specimens from the cohort confirmed that FVII is produced by the tumor and not taken up from the circulation (Figure 1B). This was further supported by FVII staining patterns reminiscent of estrogen receptor (ER) localization (supplemental Figure 1A-B).

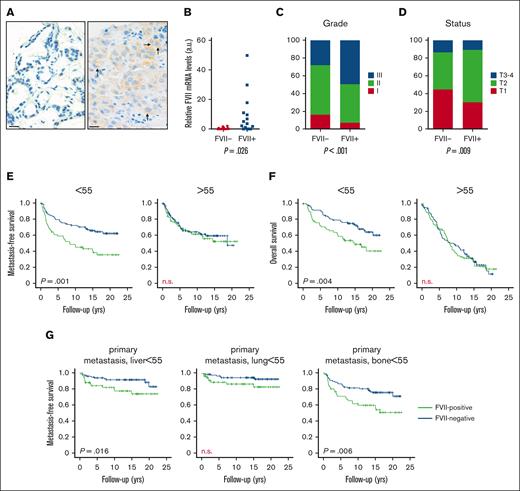

Tumor-expressed FVII expression is positively associated with breast tumor progression. (A) Representative image of a tissue microarray staining for FVII protein expression in a cohort of 574 breast tumors. (B) FVII mRNA expression was verified in 20 FVII− and 20 FVII+ tumor specimens. FVII expression is associated with grade (C) and T-status (D). (E) Metastasis-free survival in patients younger and older than 55 years. (F) Overall survival in patients younger and older than 55 years. (G) Association between FVII expression and the first-diagnosed site of metastasis.

Tumor-expressed FVII expression is positively associated with breast tumor progression. (A) Representative image of a tissue microarray staining for FVII protein expression in a cohort of 574 breast tumors. (B) FVII mRNA expression was verified in 20 FVII− and 20 FVII+ tumor specimens. FVII expression is associated with grade (C) and T-status (D). (E) Metastasis-free survival in patients younger and older than 55 years. (F) Overall survival in patients younger and older than 55 years. (G) Association between FVII expression and the first-diagnosed site of metastasis.

Tumor-expressed FVII is associated with tumor grade (Figure 1C), T-status (Figure 1D), and TF expression (supplemental Figure 1E; supplemental Table 2), but not with altered numbers of stromal cells (supplemental Figure 1E). FVII negatively associated with ER and progesterone receptor status (supplemental Figure 1E), and this was mirrored at the mRNA level (supplemental Figure 2). Moreover, FVII expression was significantly enriched in TNBC and HER2+ breast cancer (supplemental Tables 3 and 4). FVII expression was also associated with increased distal metastasis and overall survival (Figure 1E-F) (supplemental Figure 3A), but selectively in patients under 55 years of age. In these patients, FVII+ tumors preferentially metastasized to the liver and bone when compared with FVII− tumors (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 3B-D). Gene expression in FVII+ tumors from patients under 55 years of age compared with expression in FVII+ tumors from patients over 55 years of age is associated with features such as enhanced tumor proliferation and metastasis (supplemental Table 5).

TF expression in tumor cells also showed an age-dependent effect on overall survival (supplemental Figure 4) and metastasis (supplemental Figure 5A), but did not associate with liver metastasis (supplemental Figure 5B). TF expression, unlike FVII expression, was also apparent in stromal cells, but these pools of TF were not analyzed in this study (supplemental Figure 1C-D).

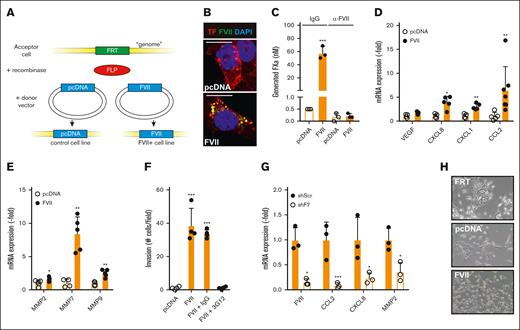

Tumor-expressed FVII induces angiogenic and invasive markers in TNBC

Although the examination of clinical samples showed an association between FVII expression and tumor progression, they failed to prove that FVII drives tumor progression. Therefore, we examined the effects of FVII expression on tumor progression in vitro. F7 and F3 mRNA expression were examined in 28 breast cancer cell lines (supplemental Figure 6). Based on high F3 and low F7 expression, we selected the TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 and transfected the cells with control (pcDNA) or human FVII cDNA using the Flp/FRT system, as described previously.2 This resulted in a cell line that is polyclonal yet contains the empty vector (MDApcDNA) or FVII cDNA (MDAFVII) in a single, well-defined genomic position (Figure 2A). FVII expression resulted in diminished TF expression (supplemental Figure 7A-B). FVII was mainly expressed in endoplasmic reticulum compartments but also colocalized with TF (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 7C). Cellular TF/FVII complexes, in the absence of exogenous FVII, enabled FXa generation, indicating coagulant activity (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 7D). From a panel of monoclonal FVII antibodies, we selected mAb-3G12 that specifically inhibits human but not murine FVIIa activity (supplemental Figure 8).18,19 Mab-3G12 completely inhibited FX activation on MDAFVII cells (Figure 2C). Adding 1 nM rFVIIa to MDAFVII cells did not increase FXa levels (supplemental Figure 7D), suggesting that TF on the cell surface was saturated with tumor-expressed FVII. FVII expression did not induce cell proliferation (supplemental Figure 7E), but stimulated the production of angiogenic mediators (VEGF, CXCL8, CXCL1, and CCL2) (Figure 2D) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2, MMP7, and MMP9) (Figure 2E) and enhanced migration (supplemental Figure 7F) and invasion (supplemental Figure 7G). Antibody blockade of FVII strongly reduced invasion of MDAFVII cells (Figure 2F). To confirm FVII-dependent gene expression in TNBC cells naturally expressing both FVII and TF, we selected MDA-MB-453 (supplemental Figure 6), a cell line that was already shown to be responsive to endogenous FVII expression.7 FVII knockdown in MDA-MB-453 by shRNA approaches reduced CCL2, CXCL8, and MMP2 levels (Figure 2G).

Effects of tumor-expressed FVII expression on cell behavior. (A) Strategy for creating FVII-expressing cells. An FRT site was inserted into the genome of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Subsequently, the gene of interest (empty vector or FVII cDNA) was inserted into the FRT site by cotransfecting a recombinase-expressing construct. Subsequently, colocalization of FVII and TF (B), coagulant activity in the presence or absence of a FVII-blocking antibody (n = 3) (C), and FVII target gene expression (n = 5) were determined in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (D-E). (F) Invasion of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells through Matrigel-coated transwell inserts in the presence of the indicated blocking antibodies (n = 4). (G) FVII-dependent gene expression in MDA-MB-453 cells after FVII knockdown by shRNA (n = 3). (H) Morphology of MDAFRT, MDApcDNA, and MDAFVII cells. Scale bars, 10 μm (B) 40 μm (H). Note the epithelial patches of FRT and pcDNA cells. All graphs show the mean and standard deviation (SD). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Effects of tumor-expressed FVII expression on cell behavior. (A) Strategy for creating FVII-expressing cells. An FRT site was inserted into the genome of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Subsequently, the gene of interest (empty vector or FVII cDNA) was inserted into the FRT site by cotransfecting a recombinase-expressing construct. Subsequently, colocalization of FVII and TF (B), coagulant activity in the presence or absence of a FVII-blocking antibody (n = 3) (C), and FVII target gene expression (n = 5) were determined in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (D-E). (F) Invasion of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells through Matrigel-coated transwell inserts in the presence of the indicated blocking antibodies (n = 4). (G) FVII-dependent gene expression in MDA-MB-453 cells after FVII knockdown by shRNA (n = 3). (H) Morphology of MDAFRT, MDApcDNA, and MDAFVII cells. Scale bars, 10 μm (B) 40 μm (H). Note the epithelial patches of FRT and pcDNA cells. All graphs show the mean and standard deviation (SD). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Tumor-expressed FVII induces loss of cell-cell adhesion

FRT+ MDA-MB-231 cells adopted a slightly more epithelial-like morphology showing colony formation, presumably because of selection (Figure 2H top). Insertion of control DNA did not change this morphology (Figure 2H middle), whereas F7 expression induced the absence of these colonies (Figure 2H bottom), suggesting that tumor-expressed FVII affects epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Gene expression profiles of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells were compared, and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis predicted roles for FVII in cancer, cell cycle, developmental pathways, and cell movement networks (supplemental Figures 9-14). Gene patterns also strongly matched those observed in neoplasia, migration, breast, colorectal, and liver cancer (supplemental Tables 6 and 7) and showed overlap with genes typically associated with TGF-β signaling (Figure 3A). The canonical TGF-β signaling was more potently induced in MDAFVII cells than in MDApcDNA cells (Figure 3B), which is consistent with reports on cross talk between PAR2 and TGF-β signaling.20 Finally, we observed that more active TGF-β1 was produced by MDAFVII cells than the control cells (supplemental Figure 15A).

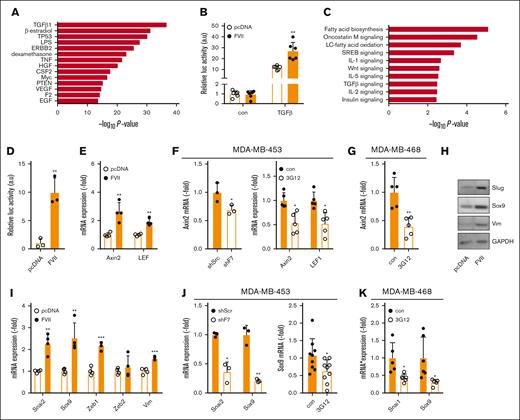

Tumor-expressed FVII-dependent expression of prometastatic genes. (A) Based on microarray analysis of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (n = 4), upstream pathways were predicted using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. (B) Activity of the canonical TGF-β pathway in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells as measured using a construct containing a SMAD3/4-controlled luciferase insert (CAGA-Luc; n = 3). (C) Pathways and processes as predicted with Enrichr. (D) Activity of the Wnt pathway in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells as measured using a construct containing a β-catenin–controlled luciferase insert (Bat-Luc; n = 3). (E) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents Axin2 and LEF1 as measured using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 3). (F) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents as measured using qPCR in MDA-MB-453 after shRNA approaches or FVII antibody blockade (n = 5). (G) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents in MDA-MB-468 after FVII antibody blockade (n = 5). (H) Western blot analysis of Slug, Sox9, and vimentin in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (I) mRNA expression of EMT factors and Sox9 in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII, as determined using qPCR (n = 4). (J) Expression of Slug and Sox9 in MDA-MB-453 after shRNA or antibody treatment (n = 5). (K) Expression of Snail and Sox9 in MDA-MB-468 after FVII antibody treatment (n = 5). All graphs show the mean and SD. Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Con, control; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL-1, interleukin 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Tumor-expressed FVII-dependent expression of prometastatic genes. (A) Based on microarray analysis of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (n = 4), upstream pathways were predicted using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. (B) Activity of the canonical TGF-β pathway in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells as measured using a construct containing a SMAD3/4-controlled luciferase insert (CAGA-Luc; n = 3). (C) Pathways and processes as predicted with Enrichr. (D) Activity of the Wnt pathway in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells as measured using a construct containing a β-catenin–controlled luciferase insert (Bat-Luc; n = 3). (E) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents Axin2 and LEF1 as measured using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 3). (F) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents as measured using qPCR in MDA-MB-453 after shRNA approaches or FVII antibody blockade (n = 5). (G) Expression of Wnt pathway constituents in MDA-MB-468 after FVII antibody blockade (n = 5). (H) Western blot analysis of Slug, Sox9, and vimentin in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (I) mRNA expression of EMT factors and Sox9 in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII, as determined using qPCR (n = 4). (J) Expression of Slug and Sox9 in MDA-MB-453 after shRNA or antibody treatment (n = 5). (K) Expression of Snail and Sox9 in MDA-MB-468 after FVII antibody treatment (n = 5). All graphs show the mean and SD. Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Con, control; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL-1, interleukin 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Additional pathway analysis using ‘Enrichr’ predicted the involvement of Wnt signaling (Figure 3C). Reporter assays indicated that canonical Wnt responses were enhanced in MDAFVII cells, (Figure 3D), and mRNA expression of the downstream Wnt target AXIN2, and LEF1, a transcription factor belonging to the Wnt pathway, were increased in FVII-expressing cells (Figure 3E). LEF1 protein levels were increased in MDAFVII cells, specifically in the nucleus (supplemental Figure 15B). Moreover, in 2 endogenously FVII-expressing TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-453 and MDA-MB-468, AXIN2 and LEF1 expression were decreased by FVII shRNA or FVII-blocking mAb-3G12 (Figure 3F-G).

We next assayed the expression of factors involved in EMT and found FVII-dependent upregulation of SNAI2 (Slug), ZEB1, SOX9, and VIM (Figure 3H-I), and Sox9 localization to the nucleus (supplemental Figure 15B). Incubation of MDApcDNA cells with MDAFVII-conditioned media did not affect SNAI2 and SOX9 levels, indicating that FVII expression influences these gene products in an autocrine manner (supplemental Figure 15C) In MDA-MB-453 cells, SNAI2 and SOX9 expression decreased after the inhibition of FVII (Figure 3J). FVII did not affect the expression of SNAI2 in MDA-MB-468 cells; however, a comparable reduction of SOX9 and SNAI1 (Snail) could be observed after 3G12 treatment (Figure 3K). Surprisingly, neither Wnt signaling nor TGF-β signaling appeared to be involved in FVII-dependent Sox9 induction (supplemental Figure 15B,D). As Sox9 is an established upregulator of LEF1,21 these data suggest that Wnt signaling is a downstream effect of Sox9 induction. These results further suggest that FVII expression stimulates EMT in TNBC.

Tumor-expressed FVII in TNBC enhances tumor progression

Expression of Snail or Slug in combination with Sox9 is associated with enhanced aggressiveness,22 suggesting that FVII-expressing cells may exhibit more aggressive tumor cell behavior. We assessed the effects of FVII expression on tumor growth in an orthotopic breast cancer model.15 MDAFVII cells yielded significantly larger tumors compared with MDApcDNA cells (Figure 4A), with significantly larger Ki67+ areas at the nonnecrotic tumor periphery (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 16A). Furthermore, an increase in intratumoral CD-31+ vessel density (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 16B), infiltrated leukocytes (Figure 4D-E; supplemental Figure 16C), and CCL2 levels (supplemental Figure 16D) were observed in MDAFVII tumors, but the amount of stroma in these tumors was not significantly different (supplemental Figure 16E-F). We also noted that, in contrast to in vitro cultured FVII cells, FVII-expressing cells in vivo displayed enhanced levels of cytoplasmic active catenin β1 (Figure 4F; supplemental Figure 16G), which was previously associated with poor survival.23 In agreement with our patient data, FVII expression resulted in increased metastasis to the liver and bone but not to the lungs (Figure 4G). Both primary tumor growth and liver metastasis were inhibited by mAb-3G12 (Figure 4H) but not by inhibitors of downstream coagulation (Figure 4I), suggesting that FVII affects cellular behavior directly. In experimental metastasis experiments, that is, the injection of tumor cells via the tail vein, MDAFVII cells did not yield more metastasis to the liver or lungs than MDApcDNA cells (Figure 4J; supplemental Figure 16H). Thus, we reasoned that FVII-dependent increase in liver metastasis is either explained by a higher tumor burden, or by effects of FVII on the metastatic capacity of the tumor cells. Therefore, metastasis was also analyzed at a similar tumor burden. Here, a sevenfold higher metastasis to the liver upon FVII expression was observed (Figure 4K; supplemental Figure 16J), but a nonsignificant effect on lung metastasis (supplemental Figure 16I,K) was observed. As we observed higher Sox9 expression in MDAFVII cells, we hypothesized that Sox9 might also be enriched in liver metastases. Therefore, a full panel of FVII-expressing metastatic cell lines isolated from lung, liver, and bone was established by mincing the target organs and subsequent culturing of the fragments, which typically leads to the outgrowth of metastatic cells from nonproliferating organ tissue. We were repeatedly unable to isolate a similar panel for MDApcDNA cells, possibly reflecting their limited aggressiveness. Nevertheless, SOX9 expression was higher in liver and bone metastatic cell lines when compared with lung cell lines (Figure 4L), suggesting that Sox9 predisposes to liver and bone metastasis. Interestingly, this corresponded with a reduction in TF (F3) mRNA levels but not EPCR (PROCR) mRNA levels (supplemental Figure 16K).

Effects of tumor-expressed FVII on tumor characteristics and metastasis. (A) Primary tumor growth after orthotopic injection of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells in immunodeficient mice (n = 6). In the extracted tumors, KI67 positivity of the outer proliferative zone (B), CD31+ vessel density (C), CD11b+ (D), F4/80+ immune cells (E), and active β-catenin (F) were determined. (G) In the same experiment, metastasis was determined in the indicated organs using qPCR of human GAPDH corrected for mouse β-actin. (H) Tumor growth and metastasis were also determined after orthotopic grafting in the presence of the FVII-blocking antibody 3G12 (n = 6). (I) Tumor growth and metastasis at the end of the experiment at week 11 were also determined in the presence of downstream coagulation inhibitors dabigatran (thrombin) or rivaroxaban (FXa) (n = 6). (J) Experimental liver metastasis after tail vein injection of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (n = 9). (K) Metastasis was also determined using qPCR at equal tumor burden (pcDNA at 11 weeks, FVII at 10 weeks; n = 8). (L) SOX9 expression in isolated lung, liver, and bone metastatic FVII cells (n = 4). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Graphs show the mean and SD. Scale bars, 40 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Effects of tumor-expressed FVII on tumor characteristics and metastasis. (A) Primary tumor growth after orthotopic injection of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells in immunodeficient mice (n = 6). In the extracted tumors, KI67 positivity of the outer proliferative zone (B), CD31+ vessel density (C), CD11b+ (D), F4/80+ immune cells (E), and active β-catenin (F) were determined. (G) In the same experiment, metastasis was determined in the indicated organs using qPCR of human GAPDH corrected for mouse β-actin. (H) Tumor growth and metastasis were also determined after orthotopic grafting in the presence of the FVII-blocking antibody 3G12 (n = 6). (I) Tumor growth and metastasis at the end of the experiment at week 11 were also determined in the presence of downstream coagulation inhibitors dabigatran (thrombin) or rivaroxaban (FXa) (n = 6). (J) Experimental liver metastasis after tail vein injection of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (n = 9). (K) Metastasis was also determined using qPCR at equal tumor burden (pcDNA at 11 weeks, FVII at 10 weeks; n = 8). (L) SOX9 expression in isolated lung, liver, and bone metastatic FVII cells (n = 4). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Graphs show the mean and SD. Scale bars, 40 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

We validated the effects of FVII on tumor progression in other TNBC cell lines. mAb-3G12 inhibited MDA-MB-468 primary tumor growth and lung metastasis significantly and liver metastasis, although not statistically significant (supplemental Figure 17A-C). We next grafted FVII shRNA and control MDA-MB-453 cells and observed a complete lack of tumor-initiating capabilities of the FVII shRNA cell line (supplemental Figure 17D). In another experiment using an MDA-MB-453 line with a different F7 shRNA but with identical biological properties, similar results were observed (supplemental Figure 17E-G). Thus, depending on the cell line used, tumor-expressed FVII either promotes primary tumor growth or promotes metastasis of TNBC.

Tumor-expressed FVII and liver-derived FVII have opposing roles in metastasis

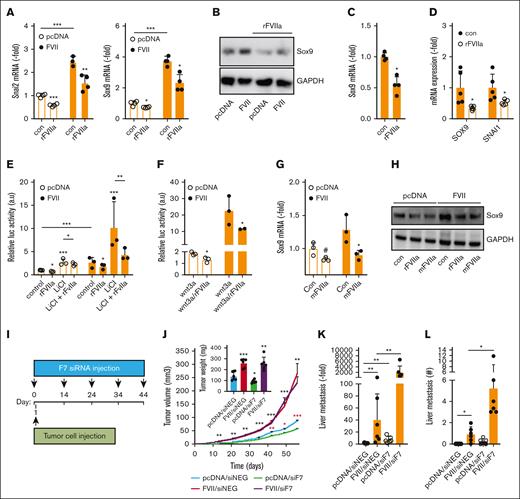

As FVII is produced by the liver and circulates in the blood, we investigated whether liver-derived FVII also contributes to cancer progression. Although tumor-expressed FVII expression in MDAFRT cells led to the expression of Slug and Sox9 mRNA and proteins, exposure to purified rFVIIa inhibited their expression in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (Figure 5A-B; supplemental Figure 18A). The inhibitory effect of rFVIIa on SNAI2 expression was strongest between 12 and 24 hours (supplemental Figure 18B) and was also observed in wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells (supplemental Figure 18C). rFVIIa inhibited SOX9 expression in MDA-MB-453 and both SNAI2 and SOX9 expression in MDA-MB-468 cells (Figure 5C-D), showing that the inhibitory effects of exogenous rFVIIa on EMT markers are a general phenomenon in TNBC cells. Concordantly, rFVIIa inhibited Wnt pathway activation in both MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells (Figure 5E) and in wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells (supplemental Figure 18D), but this was more apparent after stimulation with Wnt pathway activators LiCl or Wnt3A (Figure 5E-F).

Opposing effects of tumor-expressed and liver-derived FVII on prometastatic genes and metastasis. (A) qPCR analysis of Slug and Sox9 expression in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after vehicle or rFVIIa (n = 4). (B) Western blot analysis of Sox9 expression in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after vehicle or rFVIIa. The analysis of prometastatic gene expression was analyzed using qPCR in MDA-MB-453 (n = 5) (C) and MDA-MB-468 (n = 5) (D). (E) Effects of rFVIIa on Wnt pathway activity as determined with a β-catenin–responsive luciferase construct in the presence or absence of the Wnt pathway activator LiCl (n = 3). (F) Effects of rFVIIa on Wnt pathway activity in the presence of Wnt3A (n = 3). Effects of mFVIIa on Sox9 in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII was analyzed using qPCR (G) and western blot (H). (I) Schematic overview in time of tumor cell grafting and subsequent downregulation of liver mFVII by siRNA approaches. (J) In vivo orthotopic tumor growth of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after control (siNEG) or FVII (siF7) siRNA treatment (n = 6). Black asterisks show significant differences between tumor growth after MDAFVII graftment in the presence of siNEG vs that after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siNEG. Red asterisks show differences in tumor growth after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siNEG vs that after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siF7. (K) MDApcDNA and MDAFVII liver metastasis after control (siNEG) or FVII (siF7) siRNA treatment as determined using qPCR and histochemistry (L). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests.

Opposing effects of tumor-expressed and liver-derived FVII on prometastatic genes and metastasis. (A) qPCR analysis of Slug and Sox9 expression in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after vehicle or rFVIIa (n = 4). (B) Western blot analysis of Sox9 expression in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after vehicle or rFVIIa. The analysis of prometastatic gene expression was analyzed using qPCR in MDA-MB-453 (n = 5) (C) and MDA-MB-468 (n = 5) (D). (E) Effects of rFVIIa on Wnt pathway activity as determined with a β-catenin–responsive luciferase construct in the presence or absence of the Wnt pathway activator LiCl (n = 3). (F) Effects of rFVIIa on Wnt pathway activity in the presence of Wnt3A (n = 3). Effects of mFVIIa on Sox9 in MDApcDNA and MDAFVII was analyzed using qPCR (G) and western blot (H). (I) Schematic overview in time of tumor cell grafting and subsequent downregulation of liver mFVII by siRNA approaches. (J) In vivo orthotopic tumor growth of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII after control (siNEG) or FVII (siF7) siRNA treatment (n = 6). Black asterisks show significant differences between tumor growth after MDAFVII graftment in the presence of siNEG vs that after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siNEG. Red asterisks show differences in tumor growth after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siNEG vs that after graftment of MDApcDNA cells in the presence of siF7. (K) MDApcDNA and MDAFVII liver metastasis after control (siNEG) or FVII (siF7) siRNA treatment as determined using qPCR and histochemistry (L). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests.

Mouse FVII and human TF are compatible and xenograft models are thus suitable to study the interaction between tumor-expressed human TF, tumor-expressed human FVII, and liver-derived mouse FVII.24 To first confirm the compatibility of mFVIIa in our model, we tested the effects of mFVIIa on Sox9 mRNA and protein expression and found them to be similar to those elicited by rFVIIa (Figure 5G-H).

Next, we induced liver-specific F7 knockdown in mice by siRNA approaches in the absence of F7 knockout mice (FVII−/− induces lethality at the embryonic/perinatal stage25). This allowed us to downregulate liver-derived F7 expression to a level that fails to induce signaling while maintaining relatively functional coagulation (supplemental Figure 18E-H). Expression of other coagulation factors in the liver was not affected (supplemental Figure 18H), ruling out that siRNA treatment affected coagulation factor synthesis by the liver. Subsequently, MDApcDNA or MDAFVII cells were implanted in the mammary fat pad, and FVII siRNAs were applied (Figure 5I). Knockdown of liver-derived F7 led to a significant inhibition of tumor development of MDApcDNA cells but did not affect the expansion of MDAFVII cells (Figure 5J). In concordance with our in vitro findings, tumor-expressed FVII resulted in increased metastasis to the liver (Figure 5K-L). Remarkably, knockdown of liver-derived F7 increased MDApcDNA and MDAFVII liver metastasis compared with siRNA control (Figure 5K-L). No statistically significant increase in metastasis was observed in lung tissue (supplemental Figure 18I-J).

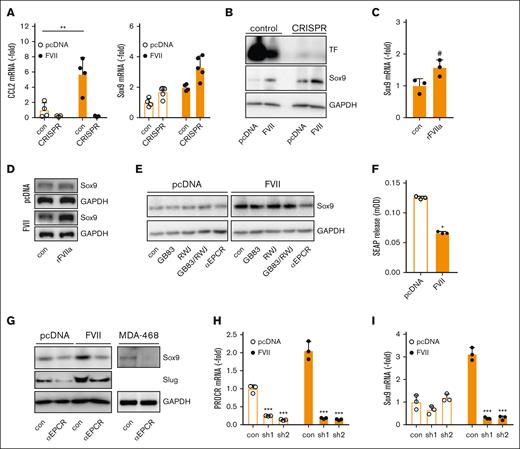

EPCR-dependent effects of tumor-expressed FVII on EMT

Next, we characterized why tumor-expressed FVII and exogenous rFVIIa have opposing effects on EMT factors and metastasis. To block the canonical TF-FVII signaling pathway, MDApcDNA and MDAFVII TF knockout cells were generated. F3 knockout reduced expression of the TF-FVII-PAR2 target CCL2 (Figure 6A), but MDAFVII cells continued to produce more Sox9 mRNA and protein despite TF deficiency (Figure 6A-B). In the absence of TF, rFVIIa showed a trend toward enhanced Sox9 levels (Figure 6C-D), confirming that canonical TF:FVIIa:PAR2 signaling inhibits Sox9. Indeed, PAR2 knockdown resulted in enhanced SOX9 and SNAI2 expression (supplemental Figure 19A-C). Stimulation with the PAR2 activator SLIGRL induced the upregulation of typical PAR2-responsive genes, such as CCL2 and CXCL8, but downregulated SOX9 and SNAI2 expression (supplemental Figure 19G-H). Knockdown of PAR1 similarly led to upregulation of SOX9 and SNAI2 mRNA (supplemental Figure 19D-F). Pharmacological PAR1 and PAR2 inhibition failed to inhibit Sox9 (Figure 6E). We next assessed the role of PAR2 in HEK293 cells expressing a chimeric protein of secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) fused to the N-terminus of PAR2. Although escalating doses of rFVIIa led to the release of SEAP, indicating PAR2 activation (supplemental Figure 19I), transiently expressed FVII inhibited basal SEAP secretion into the media, reflecting reduced basal PAR2 activation (Figure 6F). Finally, incubation of MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells with catalytically inactive FVIIa did not lead to diminished Slug or Sox9 mRNA levels, again suggesting that PAR2 activation by catalytically active FVIIa is responsible for this (supplemental Figure 19J).

FVII-induced Sox9 expression is dependent on EPCR but independent of TF and PARs. (A) Control and TF CRISPR-edited cells were analyzed for CCL2 and Sox9 expression using qPCR (n = 3). (B) Control and TF CRISPR-edited cells were analyzed for Sox9 expression using western blot. (C) Effect of rFVIIa on Sox9 mRNA levels in TF-deficient MDAFVII cells. (D) Effect of rFVIIa on Sox9 protein levels in TF-deficient MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells. (E) Effect of pharmacological PAR inhibitors on Sox9 expression. (F) PAR2 activation in HEK293 cells transfected with vector control or a FVII expression construct, as measured by SEAP release (n = 3). (G) Effect of an EPCR-blocking antibody on Sox9 and Slug expression. (H) Knockdown of the PROCR gene encoding EPCR (n = 3). (I) Effect of PROCR knockdown on Sox9 expression (n = 3). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Graphs show the mean and SD.

FVII-induced Sox9 expression is dependent on EPCR but independent of TF and PARs. (A) Control and TF CRISPR-edited cells were analyzed for CCL2 and Sox9 expression using qPCR (n = 3). (B) Control and TF CRISPR-edited cells were analyzed for Sox9 expression using western blot. (C) Effect of rFVIIa on Sox9 mRNA levels in TF-deficient MDAFVII cells. (D) Effect of rFVIIa on Sox9 protein levels in TF-deficient MDApcDNA and MDAFVII cells. (E) Effect of pharmacological PAR inhibitors on Sox9 expression. (F) PAR2 activation in HEK293 cells transfected with vector control or a FVII expression construct, as measured by SEAP release (n = 3). (G) Effect of an EPCR-blocking antibody on Sox9 and Slug expression. (H) Knockdown of the PROCR gene encoding EPCR (n = 3). (I) Effect of PROCR knockdown on Sox9 expression (n = 3). Statistically significant differences were tested using t tests. Graphs show the mean and SD.

EGFR signaling has been shown to be positively regulated by PAR2.26 In support of a negative role for PAR2 in SOX9 expression, inhibition of EGFR led to the upregulation of SOX9 in MDApcDNA, whereas EGF stimulation led to reduced SOX9 expression in MDAFVII (supplemental Figure 19K).

Another process involved in FVII(a)-dependent signaling is integrin ligation. ITGB1 levels were reduced in MDAFVII cells and upregulated in MDA-MB-453 cells upon FVII knockdown (supplemental Figure 20A). Inhibition of ITGB1 in MDAFVII did not reduce SOX9 and SNAI2 mRNA levels, but SOX9 and SNAI2 were increased in MDApcDNA cells after ITGB1 inhibition (supplemental Figure 20B), ruling out a role for integrin β1 in tumor FVII effects.

EPCR is another receptor for FVII(a).27 EPCR colocalized with FVII in membrane-localized and intracellular specks (supplemental Figure 21A). We note that EPCR is localized to the nuclear compartment, as previously reported.28,29 EPCR inhibition reduced Sox9 and Slug levels in MDAFVII cells and Sox9 in MDA-MB-468 (Figure 6E,G), which is in line with earlier reports on EPCR-dependent upregulation of Sox9.30 EPCR blockade also reduced SNAI2 expression in MDAFVII cells, SOX9 and SNAI1 expression in MDA-MB-468 cells, and SNAI2 expression in MDA-MB-453 cells (Figure 6H-I; supplemental Figure 21B-C). Importantly, incubation of cells with another EPCR-binding protein, activated protein C, did not lead to altered SNAI2 or SOX9 expression, showing that this effect is limited to FVII (supplemental Figure 19J).

Together, these results suggest that liver-derived FVII reduces prometastatic factors by binding to TF, whereas tumor-expressed FVII upregulates these factors by binding to EPCR.

Discussion

We report that tumor FVII levels are associated with decreased metastasis-free survival, particularly in patients under 55 years of age. We also report a negative association between FVII and ER/progesterone receptor expression, but positive associations with TNBC and HER2+ breast cancer. We confirmed a mechanistic role for FVII in breast cancer progression in 3 different TNBC cell lines: MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, and MDA-MB-468. FVII expression was found to enhance the expression of important EMT transcription factors such as Snail and Slug. This is corroborated by earlier reports establishing a link between coagulation factors and EMT programs.31,32

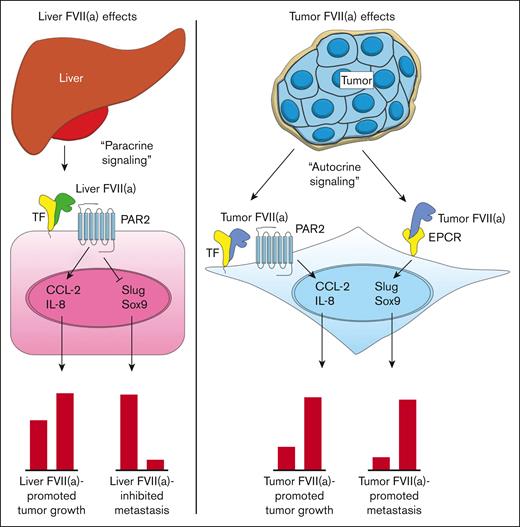

We noted that FVII was associated primarily with the occurrence of liver metastasis. This is supported by our mouse models, in which FVII expression led to enhanced liver metastasis. Our analysis in metastasis-derived cell lines suggests that Sox9, associated with stemness and aggressive behavior,22 is key in FVII-dependent liver metastasis (Figure 7). Tumor FVII also upregulates Slug, an EMT factor that stabilizes the Sox9 protein. Finally, tumor-expressed FVII upregulated prometastatic β-catenin–dependent pathways, likely via the upregulation of the β-catenin–binding partner LEF1, a downstream target of Sox9.21 In addition, EPCR has been reported30 as a stem cell marker and an effector of stemness in (non)cancerous settings, supporting a role for EPCR in tumor FVII-dependent aggressiveness. EPCR-expressing cancer-initiating cells downregulate TF concordantly with the acquisition of anchorage-independent growth. Thus, we propose that tumor-expressed FVII associates with EPCR to drive Sox9, Slug, and LEF1, thereby propelling metastasis (Figure 7). Although FVII may influence metastasis via the maintenance of cancer stem cells, given the involvement of Sox9 and EPCR, we did not investigate the influence of FVII expression on cancer stem cells.

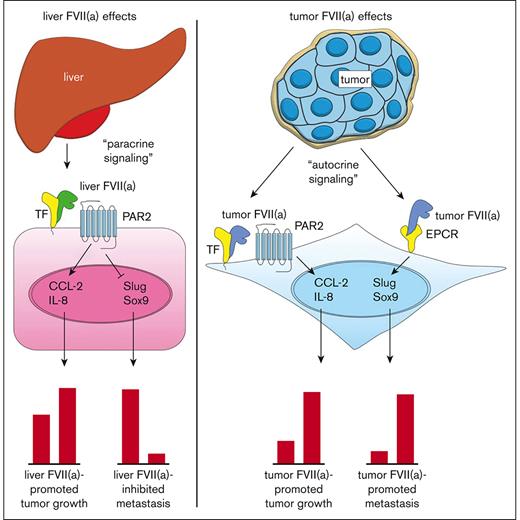

Current model for the roles of TF, recombinant FVIIa, tumor-expressed FVII, and EPCR in cancer progression. Blood-borne FVII secreted by the liver binds to TF on the tumor cell surface (tumor cell indicated in pink) (left). The TF:FVIIa complex then activates PAR2 on the tumor cell surface, leading to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors such as CCL-2 and IL-8 and subsequent tumor growth. TF:FVIIa-mediated PAR2 activation also leads to the downregulation of EMT factors such as Slug and Sox9, resulting in an epithelial-like phenotype and diminished metastasis to the liver. Tumor cells produce FVII and FVIIa in an autocrine fashion, which binds to TF or EPCR (right). Tumor FVIIa in complex with TF activates PAR2 on the tumor cell surface (tumor cells indicated in blue), leading to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors such as CCL-2 and IL-8 and subsequent tumor growth. Tumor FVIIa bound to EPCR leads to the upregulation of EMT factors such as Slug and Sox9, resulting in mesenchymal-like phenotype and enhanced metastasis to the liver.

Current model for the roles of TF, recombinant FVIIa, tumor-expressed FVII, and EPCR in cancer progression. Blood-borne FVII secreted by the liver binds to TF on the tumor cell surface (tumor cell indicated in pink) (left). The TF:FVIIa complex then activates PAR2 on the tumor cell surface, leading to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors such as CCL-2 and IL-8 and subsequent tumor growth. TF:FVIIa-mediated PAR2 activation also leads to the downregulation of EMT factors such as Slug and Sox9, resulting in an epithelial-like phenotype and diminished metastasis to the liver. Tumor cells produce FVII and FVIIa in an autocrine fashion, which binds to TF or EPCR (right). Tumor FVIIa in complex with TF activates PAR2 on the tumor cell surface (tumor cells indicated in blue), leading to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors such as CCL-2 and IL-8 and subsequent tumor growth. Tumor FVIIa bound to EPCR leads to the upregulation of EMT factors such as Slug and Sox9, resulting in mesenchymal-like phenotype and enhanced metastasis to the liver.

FVII may also drive tumor progression by eliciting differences in tumor stroma, and conceivably, tumor-expressed FVII could more readily influence tumor stromal cells. Nevertheless, we did not find stromal differences between FVII− and FVII+ tumors, except for CD11b and F4/80+ cells. Whether these cells play a role in FVII-dependent tumor progression needs to be addressed in the future. In any case, it appears that tumor-expressed FVII does not directly influence the recruitment of these cells, as FVII acted in an autocrine manner on tumor cells, as noted before.13

Another striking outcome is that rFVIIa (mimicking liver-derived FVII) and tumor-expressed FVII have opposing effects on metastasis. Importantly, tumor-expressed FVII appeared to activate TF-dependent coagulation in a saturating manner, posing the question of how rFVIIa could still exert antimetastatic effects (Figure 7). Nevertheless, it was previously shown that a coagulant (high FVII affinity) and signaling (low FVII affinity) pool of TF exist33 and we hypothesize that, although coagulant TF was saturated with tumor-expressed FVII, signaling TF was still available for rFVIIa binding. It also remains unclear why tumor-expressed FVII favors EPCR-dependent signaling, whereas rFVIIa (mimicking liver-derived FVII) favors TF/PAR2-dependent signaling. One explanation is that tumor-derived FVII and liver-derived FVII are structurally different. Nevertheless, knockdown of TF shifted rFVIIa-dependent Slug and Sox9 inhibition to rFVIIa-dependent Slug and Sox9 expression. Thus, tumor-expressed FVII and rFVIIa are likely structurally similar. Another explanation may be that tumor-expressed FVII is assembled onto EPCR intracellularly before being transported to the membrane, whereas liver FVII binds TF extracellularly. This corresponds with the fact that we did not observe any free levels of tumor FVII in MDAFVII−conditioned media (not shown). In any case, roles for PAR1, integrin β1, and EGFR as coreceptors were ruled out.

Although a role for liver-derived FVII in antimetastatic effects is at odds with earlier studies showing that blood coagulation spurs metastasis by forming a fibrin and platelet–rich protecting shield around metastatic cells, it must be mentioned that coagulation was only minimally affected in our model, whereas FVII levels in our model are typically incapable of initiating signal transduction.5 Thus, we propose that TF:FVIIa:PAR2 signaling affects tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth while inhibiting metastasis (Figure 7). Possibly liver-derived FVII drives a more epithelial phenotype typically associated with tumor growth but not with metastasis. Once the cancer cells intravasate, TF signaling-dependent inhibition of metastasis switches to TF coagulation-dependent stimulation of cancer cell metastasis, as previously reported.34

A final note of interest is the fact that FVII signaling affected tumor growth, whereas pharmacological inhibition of downstream coagulation, as noted earlier,16 was without effect. This suggests that TF:FVII and EPCR:FVII signaling, but not FX or thrombin, are important mediators of cancer progression. Anticoagulation has often been suggested to affect metastasis; however, our data suggest that the current direct oral anticoagulants are not suited for breast cancer treatment.

Despite the findings in this report, several limitations remain. First, the use of breast cancer cell lines in our research is a potential caveat, and determining the role of FVII in models that more closely mimic human disease is warranted. Second, it remains unknown how tumor-expressed FVII is activated to FVIIa. Earlier reports indicate that hepsin, a transmembrane protease expressed by cancers, may activate FVII.35 Finally, we wish to indicate that the link between tumor-expressed FVII and tumorigenicity may not be absolute. For instance, low FVII-expressing SKBR7 cells are tumorigenic,36 whereas high FVII-expressing BT474 cells grow slowly in vivo. Thus, the action of FVII may be context-dependent (eg, the genetic makeup of the cells).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caroline Spaargaren-van Riel and El Houari Laghmani for technical assistance. G. van der Pluijm is acknowledged for his kind gift of transforming growth factor β–responsive luciferase plasmids and P. ten Dijke for his gift of WNT-responsive luciferase plasmids. Finally, the authors thank A. G. Jochemsen for his kind gift of breast cancer cell lines.

This study was funded in part by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (UL 2015-7594), Worldwide Cancer Research (15-1186), and Department of Molecular Medicine, Scripps Research from the National Institutes of Health (HL104165 and HL130678 [L.O.M.]).

Authorship

Contribution: C.K., C.T., B.K., S.C.C., and J.T.B. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; E.J.B., B.U., Y.W.v.d.B., E.S., M.Y.K., N.S., D.E.M.D., Y.L., L.V.E.O., R.F.P.v.d.A., L.J.H., and B.J.M.v.V. performed experiments and edited the manuscript; L.O.M., W.R., and P.J.K. provided reagents and/or tissue specimens, contributed to the experimental design, and edited the manuscript; H.H.V. supervised the study, analyzed and discussed data, and wrote the manuscript; and M.P., E.J.B., B.U., Y.W.v.d.B., E.S., M.Y.K., N.S., D.E.M.D., Y.L., L.V.E.O., R.F.P.v.d.A., L.J.H., B.J.M.v.V., and X.Z. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Henri H. Versteeg, Department of Internal Medicine, Leiden University Medical Center, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: h.h.versteeg@lumc.nl.

References

Author notes

∗C.K., C.T., and B.K. contributed equally to this study.

Microarray data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE120047).

Availability of human tumors is restricted owing to ethical considerations. Cell lines and antibodies are freely available. Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Henri H. Versteeg (h.h.versteeg@lumc.nl).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.