Abstract

The International Staging Evaluation and Response Criteria Harmonization for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma (SEARCH for CAYAHL) seeks to provide an appropriate, universal differentiation between E-lesions and stage IV extranodal disease in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). A literature search was performed through the PubMed and Google Scholar databases using the terms “Hodgkin disease,” and “extranodal,” “extralymphatic,” “E lesions,” “E stage,” or “E disease.” Publications were reviewed for the number of participants; median age and age range; diagnostic modalities used for staging; and the definition, incidence, and prognostic significance of E-lesions. Thirty-six articles describing 12 640 patients met the inclusion criteria. Most articles reported staging per the Ann Arbor (72%, 26/36) or Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor staging criteria (25%, 9/36), and articles rarely defined E-lesions or disambiguated “extranodal disease.” The overall incidence of E-lesions for patients with stage I-III HL was 11.5% (1330/11 602 unique patients). Available stage-specific incidence analysis of 3888 patients showed a similar incidence of E-lesions in stage II (21.2%) and stage III (21.9%), with E-lesions rarely seen with stage I disease (1.1%). E-lesions likely remain predictive, but we cannot unequivocally conclude that identifying E-lesions in HL imparts prognostic value in the modern era of the more selective use of targeted radiation therapy. A harmonized E-lesion definition was reached based on the available evidence and the consensus of the SEARCH working group. We recommend that this definition of E-lesion be applied in future clinical trials with explicit reporting to confirm the prognostic value of E-lesions.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a relatively rare cancer with excellent cure rates; but because of differences in staging criteria and risk stratification, outcomes cannot be directly compared between clinical trials.1-6 HL primarily affects the lymph nodes and the spleen but extranodal involvement does occur. The 1965 Rye Classification stated that involvement of the bone marrow, lung parenchyma, pleura, liver, bone, skin, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, or any tissue outside of the lymphatic system was considered stage IV disease.7 Musshoff8 first noted that extralymphatic disease contiguous with a region of lymphatic involvement treated with intensive radiotherapy alone does not have the same poor prognostic implication as widespread extralymphatic disease; he divided the existing Rye Classification group IV into stage IV per continuitatem and stage IV per disseminationem.8 This led to proposals of the subclassification of “EN”8 or subscript “E”9 for extralymphatic disease within stages I, II, and III HL; “E-lesions” were initially defined as proximal or contiguous extranodal extensions that did not require modification of the nodal irradiation field or dose and did not have negative prognostic implications.10 These findings were incorporated into a new classification system9 and disease staging procedures11 defined at the Ann Arbor meeting in 1971 that were rapidly and widely adopted for adult and pediatric HL.10

Over time, this definition has continued to be modified and studied. In 1982, Yarnold showed that disease that is contiguous but too large to meet this radiotherapy definition, is associated with a poor prognosis (possibly worse than other stage IV without this feature).12 In 1984, the complexity of staging E-lesions was demonstrated when 14 internationally recognized HL centers disagreed on the classification (E-lesion vs stage IV) of 4 representative cases of nearby but not contiguous extranodal disease of the lung or bone; 2 cases were complete stalemates.13 The subsequent 1989 Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor staging system incorporated success with chemotherapy in early unfavorable disease, improved imaging diagnostics (computed tomography [CT] and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), and prognostic advancements (bulk disease and number of involved nodal sites as risk factors); the E-lesion definition was retained with different examples of local extralymphatic organ involvement provided.10

In 2011, a dramatic change for adult HL staging was made in Lugano, Switzerland in response to outcomes with the widespread use of chemotherapy and combined modality therapy (CMT).14 This update deemed “E” subclassification no longer clinically relevant for advanced-stage disease (stages IIx, III, and IV); the “E” distinction remains meaningful in cases of limited extranodal disease in the absence of nodal involvement (stage IE) or for patients with stage II disease and direct extension to a nonnodal site (stage IIE).14 Notably, these modifications have not been applied to the pediatric population.

Agreement regarding E-lesions vs disseminated extranodal disease is challenging and yet essential for both individual patients and the interpretation of clinical trials. Central imaging reviews for large cooperative group studies have shown that discrepancies in the identification of E-lesions affect both the stage and potential treatment for individual patients.15,16 Further emphasizing the importance of appropriate identification of E-lesions, the presence of extranodal disease is used as a poor prognostic criterion to identify unfavorable early-stage disease by the adult German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG)17,18 and in the determination of treatment groups in the EuroNet Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma (PHL) C1 and C2 trials.19,20 Inappropriate patient risk assignment may lead to inappropriate conclusions drawn about the effectiveness of a given treatment regimen. The distinction between patients with local (E-lesions) or disseminated (stage IV) extranodal HL is often unclear in the literature, making it challenging to determine the prognostic value of either group.

The International Staging Evaluation and Response Criteria Harmonization for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult HL (SEARCH for CAYAHL) initiative provides a platform for global collaboration to improve the cure rates of children with HL by achieving consensus between consortia.21 As part of this effort, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on the reporting of E-lesions in patients with HL. Here, we propose a universally acceptable and harmonized definition for E-lesions in pediatric patients with HL.

Methods

Search strategy

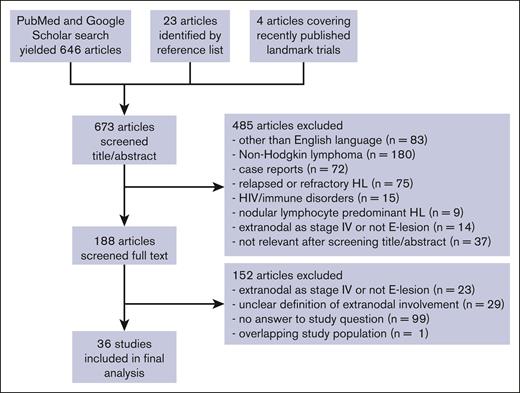

A systematic literature search was performed through the PubMed and Google Scholar databases for articles on E-lesions in patients with HL for articles published from 1 January 1960 to 1 August 2022 by using the combination of free-text keywords: “Hodgkin disease” [MeSH] AND (extranodal OR extralymphatic OR “E lesions” OR “E stage” OR “E disease”; Figure 1). Two authors (E.A.M.Z. and A.B.) independently screened each abstract per screening criteria for articles published from January 1960 to December 2016; if no exclusion criteria were met, the full manuscript was retrieved and reviewed. Reasons for exclusion were recorded. Reference lists were reviewed for additional candidate papers. A third author (J.Z.) repeated this process using the same search terms to screen articles published from 1 January 2017 to 1 August 2022. Although they did not meet the search criteria, several additional contemporary landmark trials (EuroNet PHL-C1, Hodgkin Lymphoma High Risk protocol 13, and GHSG Hodgkin's disease [HD]17) were also reviewed for inclusion. The date of the last database search was 6 September 2022. The manuscript was amended to add 1 significant recent publication that was published while this manuscript was under review. A fourth author (J.E.F.) reviewed articles as needed to determine appropriateness of inclusion or clarify interpretation.

Flowchart of literature search. Diagram representing information flow in the review of literature describing E-lesions in studies of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Flowchart of literature search. Diagram representing information flow in the review of literature describing E-lesions in studies of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles met criteria for inclusion if they offered information on the incidence or prognostic significance of E-lesions in HL and gave an explicit definition of E-lesions or reference staging per the Ann Arbor classification, the Cotswold modification, or Lugano criteria, or treatment protocols with E-lesion definitions. Acceptable examples of staging classifications and the latest international treatment protocols are listed in Tables 1-2.19,20 We included articles without explicit definitions of extranodal involvement if they were limited to stages I-III, as the term “extranodal” could not be referring to stage IV disease in these patients. All patient ages were included, because many articles combined both pediatric and adult patients.

Definitions of E-lesions in different classification systems

| Year . | Classification . | Reference . | Definition of E-lesions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Rye classification | 7 | E-lesions undefined |

| Involvement of tissue outside of the lymphatic system considered stage IV disease | |||

| 1971 | Ann Arbor classification | 9 | Stage IE: a single extralymphatic organ or site |

| Stage IIE: localized involvement of extralymphatic organ or site and ≥1 lymph node regions on 1 side of the diaphragm | |||

| Stage IIIE: involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm with localized involvement of extralymphatic organ or site | |||

| Examples: multiple nodules in the lung limited to 1 lobe or perihilar extension associated with ipsilateral hilar adenopathy; unilateral pleural effusion with or without lung involvement but with hilar adenopathy | |||

| Liver involvement is considered stage IV/diffuse disease | |||

| 1989 | Cotswolds modification of Ann Arbor classification | 10 | Involvement of extralymphatic tissue on 1 side of the diaphragm by limited direct extension from an adjacent nodal site (ie, extranodal extension) with implicit expectation of prognosis equivalent to that for treatment of nodal disease of same anatomical extent |

| May also include a discrete single extranodal deposit consistent with extension from a regionally involved node | |||

| A single extralymphatic site as the only site of disease should be classified as stage IE; multiple extranodal deposits not included | |||

| Anterior extension of a mediastinal mass into the sternum or chest wall or extension to lung or pericardium should be recorded as extranodal extension | |||

| Extensive extranodal disease is designated stage IV | |||

| 2011 | ICML staging Lugano criteria | 14 | Stage IE: single extranodal lesion without nodal involvement |

| Stage IIE: stage I or II by nodal extent with limited contiguous extranodal involvement | |||

| Stage IIx, stage III, and stage IV: not applicable |

| Year . | Classification . | Reference . | Definition of E-lesions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Rye classification | 7 | E-lesions undefined |

| Involvement of tissue outside of the lymphatic system considered stage IV disease | |||

| 1971 | Ann Arbor classification | 9 | Stage IE: a single extralymphatic organ or site |

| Stage IIE: localized involvement of extralymphatic organ or site and ≥1 lymph node regions on 1 side of the diaphragm | |||

| Stage IIIE: involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm with localized involvement of extralymphatic organ or site | |||

| Examples: multiple nodules in the lung limited to 1 lobe or perihilar extension associated with ipsilateral hilar adenopathy; unilateral pleural effusion with or without lung involvement but with hilar adenopathy | |||

| Liver involvement is considered stage IV/diffuse disease | |||

| 1989 | Cotswolds modification of Ann Arbor classification | 10 | Involvement of extralymphatic tissue on 1 side of the diaphragm by limited direct extension from an adjacent nodal site (ie, extranodal extension) with implicit expectation of prognosis equivalent to that for treatment of nodal disease of same anatomical extent |

| May also include a discrete single extranodal deposit consistent with extension from a regionally involved node | |||

| A single extralymphatic site as the only site of disease should be classified as stage IE; multiple extranodal deposits not included | |||

| Anterior extension of a mediastinal mass into the sternum or chest wall or extension to lung or pericardium should be recorded as extranodal extension | |||

| Extensive extranodal disease is designated stage IV | |||

| 2011 | ICML staging Lugano criteria | 14 | Stage IE: single extranodal lesion without nodal involvement |

| Stage IIE: stage I or II by nodal extent with limited contiguous extranodal involvement | |||

| Stage IIx, stage III, and stage IV: not applicable |

ICML, International Conference on Malignant Melanoma.

Definitions of E-lesions in recent pediatric treatment protocols

| Protocol(s) . | Reference . | Definition of E-lesions . |

|---|---|---|

| EuroNet PHL C1 | 19 | Extralymphatic structures or organs that are infiltrated per continuum out of a lymphatic mass are termed E-lesion (eg, lung, intestine, and bones) and do not automatically qualify for stage IV. Exceptions: liver or bone marrow involvement always implies stage IV |

| Pleura and pericardium: pleura and/or pericardial involvement are generally considered E-lesions. Involvement of the pleura is assumed if: the lymphoma is contiguous with the pleura without fat lamella, the lymphoma invades the chest wall, or a pleural effusion occurs, which cannot be explained by a venous congestion. Pericardial involvement is assumed if: the lymphoma has a broad area of close contact toward the heart surface beyond the valve level (ventriculus area), or a pericardial effusion occurs | ||

| Lung: a disseminated lung involvement (implying stage IV) is assumed if there are >3 foci or an intrapulmonary focus has a diameter of >10 mm. E-lesion of the lung is restricted to 1 pulmonary lobe or perihilar extension with homolateral hilar lymphadenopathy | ||

| Spleen: exclusive splenic involvement without other lymphatic disease is classified as stage I. Mere enlargement of liver/spleen only is not considered as involvement. Focal changes in the liver/ spleen structure that are tumor suspicious in ultrasonography are considered involved, independent of the FDG-PET result | ||

| EuroNet PHL C2 | 20 | An E-lesion is a contiguous infiltration of a lymph node mass into extralymphatic structures or organs (eg, lung or bone). Disseminated organ involvement always implies stage IV. |

| Pleural effusion is not considered to be an E-lesion. Involvement of the pleura is assumed if an adjacent nodal lesion infiltrates the pleura or chest wall AND the infiltrate and/or the adjacent nodal lesion is PET positive. | ||

| Pericardial effusion is not considered to be an E-lesion. Pericardial involvement is assumed if an adjacent nodal lesion infiltrates the pericardium AND the infiltrate and/or the adjacent nodal lesion is PET positive. | ||

| Lung: disseminated lung involvement is assumed if there are >2 small foci between 2 mm and 10 mm within the whole lung, or there is at least 1 intrapulmonary focus with a diameter of ≥10 mm | ||

| COG AHOD0031 & AHOD1331 | Clinical trial∗ | Extralymphatic structures contiguous with sites of lymph node involvement are considered E-lesions (particularly lung). Pleural, pericardial, or chest wall infiltration by an adjacent nodal lesion, that is, PET positive would be considered an E-lesion. Liver and/or bone marrow involvement is not considered an E-lesion but rather considered stage IV. Pleural and pericardial effusions alone are not considered E-lesions. |

| Stage IE: localized involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site | ||

| Stage IIE: localized contiguous involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site and its regional lymph node(s) with involvement of ≥1 lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm | ||

| Stage IIIE: involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm accompanied by localized contiguous involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site | ||

| Stage IV: disseminated (multifocal) involvement of ≥1 extralymphatic organs or tissues, with or without associated lymph node involvement, or isolated extralymphatic organ involvement with distant (nonregional) nodal involvement |

| Protocol(s) . | Reference . | Definition of E-lesions . |

|---|---|---|

| EuroNet PHL C1 | 19 | Extralymphatic structures or organs that are infiltrated per continuum out of a lymphatic mass are termed E-lesion (eg, lung, intestine, and bones) and do not automatically qualify for stage IV. Exceptions: liver or bone marrow involvement always implies stage IV |

| Pleura and pericardium: pleura and/or pericardial involvement are generally considered E-lesions. Involvement of the pleura is assumed if: the lymphoma is contiguous with the pleura without fat lamella, the lymphoma invades the chest wall, or a pleural effusion occurs, which cannot be explained by a venous congestion. Pericardial involvement is assumed if: the lymphoma has a broad area of close contact toward the heart surface beyond the valve level (ventriculus area), or a pericardial effusion occurs | ||

| Lung: a disseminated lung involvement (implying stage IV) is assumed if there are >3 foci or an intrapulmonary focus has a diameter of >10 mm. E-lesion of the lung is restricted to 1 pulmonary lobe or perihilar extension with homolateral hilar lymphadenopathy | ||

| Spleen: exclusive splenic involvement without other lymphatic disease is classified as stage I. Mere enlargement of liver/spleen only is not considered as involvement. Focal changes in the liver/ spleen structure that are tumor suspicious in ultrasonography are considered involved, independent of the FDG-PET result | ||

| EuroNet PHL C2 | 20 | An E-lesion is a contiguous infiltration of a lymph node mass into extralymphatic structures or organs (eg, lung or bone). Disseminated organ involvement always implies stage IV. |

| Pleural effusion is not considered to be an E-lesion. Involvement of the pleura is assumed if an adjacent nodal lesion infiltrates the pleura or chest wall AND the infiltrate and/or the adjacent nodal lesion is PET positive. | ||

| Pericardial effusion is not considered to be an E-lesion. Pericardial involvement is assumed if an adjacent nodal lesion infiltrates the pericardium AND the infiltrate and/or the adjacent nodal lesion is PET positive. | ||

| Lung: disseminated lung involvement is assumed if there are >2 small foci between 2 mm and 10 mm within the whole lung, or there is at least 1 intrapulmonary focus with a diameter of ≥10 mm | ||

| COG AHOD0031 & AHOD1331 | Clinical trial∗ | Extralymphatic structures contiguous with sites of lymph node involvement are considered E-lesions (particularly lung). Pleural, pericardial, or chest wall infiltration by an adjacent nodal lesion, that is, PET positive would be considered an E-lesion. Liver and/or bone marrow involvement is not considered an E-lesion but rather considered stage IV. Pleural and pericardial effusions alone are not considered E-lesions. |

| Stage IE: localized involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site | ||

| Stage IIE: localized contiguous involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site and its regional lymph node(s) with involvement of ≥1 lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm | ||

| Stage IIIE: involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm accompanied by localized contiguous involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site | ||

| Stage IV: disseminated (multifocal) involvement of ≥1 extralymphatic organs or tissues, with or without associated lymph node involvement, or isolated extralymphatic organ involvement with distant (nonregional) nodal involvement |

COG, Children’s Oncology Group; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose.

AHOD0031 clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00025259; AHOD1331 clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02166463. EuroNet-PHL-C1 clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00433459. EuroNet-PHL-C2 clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT02684708.

Articles were excluded if they were case reports or written in languages other than English, or if the study population did not include frontline classical HL (ie, nodular lymphocyte predominant HL, only relapsed or refractory HL, or patients with HIV or other immune disorders). We also excluded articles with unclear or incomplete definitions of extranodal or extralymphatic involvement. This encompassed the exclusion of articles that did not distinguish between E-lesions and stage IV extranodal involvement in their descriptive tables or analyses.

Outcomes

Two authors (E.A.M.Z. and A.B.) independently extracted data from identified articles published from January 1960 through December 2016; a third author (J.Z.) extracted data from articles published from 1 January 2017 through 1 August 2022. The following data were extracted from each article and recorded in a spreadsheet: the number of participants, median age and age range of participants at diagnosis, type of diagnostic tool(s) used for staging, the incidence of E-lesions, treatment, and the prognostic value of E-lesions. One author (J.Z.) manually verified all extracted data on a second occasion. Overall and stage-specific incidences of E-lesions were calculated. Pairs of articles with overlapping patient populations were individually considered for inclusion in incidence calculations; attempts were made to maximize sample size and minimize double counting. Incidence calculations were repeated without articles that used risk-based inclusion criteria (with exception of disease stage) to evaluate for selection bias.

Results

Study selection

Our literature search produced 646 unique articles; 23 additional articles were identified within the reference lists of these publications, and 4 articles reporting on contemporary landmark trials were also reviewed. After screening the abstracts, 485 were excluded per our screening criteria. We reviewed 188 full-text articles and excluded an additional 152 publications (Figure 1). In total, 36 articles were included in our final incidence analysis (Table 3). Several articles contained overlapping patient populations. If the articles provided meaningfully distinct incidence and/or prognostic information, they were both included and collated under the same study number.

Summary of studies included in incidence analysis

| Study . | Year . | Author . | Reference . | Study period . | n∗ . | Median age, y (range) . | Staging criteria . | E-Lesion location (n) . | Staging tools . | Incidence of E-lesions by stage . | Treatment (E/total, % with E-lesion) . | Impact of E-lesions on prognosis, notable covariates . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I . | II . | III . | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1977 | Mill et al | 55 | 1968-1972 | 116 | nd | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR w/wo chest tomog, IVP, L/S, LAG, BMBx, lap (58%). | IA: 0% (0/23) | IIA: 4% (2/51) | IIIA: 4% (1/24) | RT (IFRT, EFRT, TNI) vs CMT | There were more relapses in E-lesion group (statistical significance, nd). |

| IB: 0% (0/2) | IIB: 19% (3/16) | na | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 1977 | Levi et al | 22† | 1968-1976 | 111 | (9-60) | Ann Arbor | Lung only (12), lung + other (2), thyroid (2), and subcutaneous (1) | CXR w/wo chest tomog (4%); EBx (8); lap (100%). | IA: 0% (0/9) | IIA: 12% (6/50) | IIIA: 18% (7/40) | Randomized: cobalt EFRT alone (16%, 11/67) vs CMT: LFRT followed by 3-6× MOPP (16%, 7/44) | E-lesions were associated with significantly more relapses, shorter remission duration, and worse OS in EFRT-only group but not in CMT group. Strong association between lung E-lesions, moderate to large mediastinal masses, and subsequent marginal recurrences. |

| na | IIB: 42% (5/12) | na | ||||||||||||

| 1982 | Wiernik and Slawson | 23‡ | 1966-1981 | 177 (62 unique) | nd | Ann Arbor | Majority pulmonary involvement by direct extension from MMT | Chest tomog; lap (100%). | I-III: 33/177 (19%) | Randomized to EFRT alone (19%, 20/106) vs CMT: RT and 6× MOPP (18%, 13/71) | ||||

| 3 | 1982 | Hoppe et al | 25‡ | 1968-1978 | 230 | nd | Ann Arbor | Lung (28), pleura (2), bone (6), pericardium (13), soft tissue (5), and myocardium (1) | CXR (90%); LAG, lap (100%). | I/II: 17% (40/230) | na | Randomized per H1, H2, H4, R1, K1, S1, S2, and S3: EFRT alone (8%, 9 of 109) vs CMT (26%, 8/121): IFRT (I-IIA), STNI (I-IIA, IIAE), or TLI (I-IIB, IIBE) then MOP(P) or PAVe | E-lesions were not a significant factor for OS or FFR within treatment groups. | |

| 1986 | Crnkovich et al | 26† | 1968-1982 | 126 | 26 | Ann Arbor | Lung (31), pericardium (14), pleura (11), bone (5), and other (6) | CXR, BMBx, LAG; most chest tomog/CT, lap (94%) | na | IIB: 33% (41/126) | na | TLI (18%, 13/73,); 18 pts CMT (53%, 28/53) most MOPP or PAVe | E-lesions were not a significant factor for 10-year OS and FFR between treatment groups. | |

| 4 | 1984 | Zagars and Rubin | 56 | 1969-1981 | 91 | 25 | Ann Arbor | Lung, pleura, pericardium, and thoracic wall | CXR, w/wo chest tomog/CT, LAG, w/wo lap with splenectomy | IA: nd | IIA:12% (6/51) | na | All RT (TNI or STNI), 8% CMT | E-lesions associated with significantly more relapses in stage IIA treated with RT alone. In 2 cases, mediastinal masses may have driven poor prognosis. In a small portion with CMT, E-lesions did not show negative prognostic implication. |

| 5 | 1985 | Zittoun et al | 34 | 1976-1981 | 335 | (15-74) | Ann Arbor | Mediastinal involvement | CXR, chest tomog, LAG, BMBx | I, II, and IIIA: 6% (20/335) | All CMT: 3×/6× MOPP and randomized to EFRT (4%, 7/166) vs IFRT (8%, 13/169) | Patients with stage IIE disease had significantly worse 5-year DFS than defined low-risk groups. | ||

| 6 | 1985 | Leslie et al | 35 | 1969-1980 | 307 | (3 to > 40) | Ann Arbor | Lung (13), pericard (5), chest wall (3), and other (4) | CXR w/wo chest tomog/CT, LAG, lap with splenectomy (100%) | IA-IIB supradiaphragmatic: 8% (25/307) | na | IA, IIA: RT alone; IB & IIB: RT alone or CMT with MOPP; RT mostly MPA | When analyzed by mediastinal size, E-lesions did not influence FFR or OS. Among patients with E-stage disease, 11 of 25 had B-symptoms and 13 of 25 had bulk disease. | |

| 7 | 1989 | Loeffler et al | 28†,§ | 1983-1988 | 89 | 28 (15-56) | Ann Arbor | Mostly massive lung involvement | CXR, abd CT & U/S, BMBx, SS; lap or liver bx/BMBx/LAG; optional: chest CT, L/S, skeletal XR | IA: 0% (0/1) | IIA: 28% (8 of 29); IIB: 24% (5/21) | IIIA: 8% (3/38) | Per HD1: (I-III with LMT, E-stage, and/or MSI): All CMT with 2× ABVD/COPP and EFRT or TNI; bulk RT boost; stage IIIA TNI | E-lesions had no prognostic significance for CR rate, FFTF, OS, or FFP. Six of the patients with stage IIAE disease and 5 of the patients with stage IIBE disease also had MLT. |

| 1997 | Loeffler et al | 27‡,§ | HD1: 1984-1988 | HD1 147 | (15-60) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, chest CT, abd CT and U of S, BMBx, liver biopsy, NM BS; optional studies: L/S, LAG, skeletal XR (lap recommended in HD1, but not HD5) | HD1, I-IIIA + risk factors: 41% (31/147) | Per HD1 & HD5: (I-III with LMT, E-stage, and/or MSI): all CMT with 2× ABVD/COPP and EFRT or TNI; bulk RT boost | Despite E-lesions not routinely irradiated (lung pleura), there were 100% local CR and no relapses after chemotherapy (median follow-up, 6.5 y). | |||

| HD5: 1988--1993 | HD5 111 | 31 (16-62) | HD5, I-IIIA + risk factors: 27% (30/111) | |||||||||||

| 8 | 1989 | Leopold et al | 36§ | 1969-1984 | 92 | (9-50) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, abd CT or LAG, BMBx, lap and splenectomy (74%, TG 1 and 2) | CS IA-IIB with LMA --> PS IA-IIIB: 29% (27/92) | TG 1: RT only with MPA, TNI, or whole-lung RT (17%, 6/38); TG 2&3: CMT with MOPP and IFRT, MRT, MPA, or TNI (39%, 21/54) | E-lesions had no significant effect on 12-year relapse rate or survival within treatment groups. | ||

| 9 | 1992 | Oberlin et al | 32 | 1982-1988 | 217 (IV, 21) | 10 (2-18) | Ann Arbor | Pleura (4), pericardium and pleura (1), thoracic wall (2), and lung (3). | CXR w/wo chest CT, LAG, BMBx | I-III: 5% (10/217) | TG1: ABVD only, TG2-4: CMT with ABVD w/wo MOPP, IF-RT w/wo LSF | Four patients with E-lesions (40%) had local relapses, (statistical significance, nd). Two of these had bulky disease. | ||

| 10 | 1999 | Shah et al | 37 | 1970-1995 | 106 | 14 (3-22) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C (61%) or CT A (78%) or CT P (73%), L/S (60%), LAG (50%), NM BS (34%), NI (84%), lap (60%), w/wo BMBx | Supradiaphagmatic I/II: 3% (3/106) | na | RT, IFRT, mantle only, TNI, STNI | E-lesions had no significant influence on relapse rate, OS, or EFS. | |

| 11 | 2000 | Franklin et al | 18§ | 1988-1994 | 712 | (15-75) | Ann Arbor | nd | nd | I-IIIA: 12% (85 of 712) | Per HD5: CMT with COPP/ABVD or COPP/ABV/IMEP, followed by EFRT, bulk RT boost | Patients with E-lesions, especially IIBE and IIIE, had a poor prognosis at 5 years. E-lesions were a significant poor prognostic factor beyond IPS. | ||

| na | IIB-IIIA: 5% (35/712) | |||||||||||||

| 2002 | Sieber et al | 29‡,§ | 1988-1993 | 973 | 31 (16-74) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, BMBx, liver bx | I, II, and IIIA: 12% (113/973) | 7-year FFTF and CR rate significantly worse in both treatment arms. | ||||

| 12 | 2001 | Ruhl et al | 33 | 1995-2000 | 730 (IV, 100) | 14 (maximum 18) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | Pleura, pericardium, and anterior thoracic wall | CXR, chest CT, abd CT/MRI; US th/ abd/ LN; w/wo neck CT/MRI, NM BS, BMBx, lap/liver bx | 0% (0/58) | IIA: 27% (100/365) | IIIA: 33% (25/75) | Per GPOH-HD 95: all 2× OEPA/OPPA, w/wo 2× or 4× COPP; response-adapted IFRT | E-lesions were a significant risk factor for both progressive disease and relapse. |

| na | IIB: 53% (66/125) | IIIB: 27%(25/91) | ||||||||||||

| 13 | 2002 | Dieckmann et al | 15 | 1990-1995 | 518 (IV, 60), precentral review | 12 (2-17) | Ann Arbor | Pericardium, lung, chest wall, and pleura. | CXR, CT C/A/P, U/S (neck, axilla, abd, pelvis), w/wo lap, w/wo BMBx | IA: 1% (1/98); IB: 0% (0/7) | IIA: 9% (20/218); IIB: 18% (14/78) | IIIA: 12% (7/59); IIIB: 15% (9 of 58) | Per GPOH-HD-90: TG1 (I/IIA) 2× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); TG2 (IIB/IIIA/IE/IIEA); 4× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); TG3 (IIIB/IV/IIEB/IIIE) 6× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); all groups received local RT to initially involved areas (25 Gy TG 1&2; 20 Gy TG3; w/wo 5-10 Gy boost) | nia |

| 494 (IV, 84), postcentral review | IA: 0% (0/89); IB: 0% (0/5) | IIA: 15% (33/214); IIB: 37% (29/78) | IIIA: 24% (13/55); IIIB: 21% (11/53) | |||||||||||

| 14 | 2003 | Glimelius et al | 38 | 1985-1994 | 99 | 33 (17-59) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, abd US, BMBx | na | IIB: 11% (11/99) | na | CT 6-8× MOPP/ABVD, RT | Not significant in 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival |

| 15 | 2003 | Hodgson et al | 39 | 1981-1996 | 324 | 29 (15-78) | Ann Arbor | Lung or chest wall. | Chest CT | I-II: 12% of (40/324) lung invasion | na | All CMT | 5-year OS: no significant effect | |

| I-II: 7% (22/324) of chest-wall invasion | Chest wall significantly worse; 5-year CSS and DFS: lung extension no significant effect | |||||||||||||

| 16 | 2004 | Hudson et al | 40§ | 1993-2000 | 115 (IV, 44) | 15 (2-19) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT with contrast neck/C/A/P (or MRI for A/P) | I-II with risk factors or III: 10% (11/115) | na | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extranodal involvement. | ||

| 17 | 2004 | Vassilakopoulos et al | 41 | 1980-2001 | 367 | 30 (14-82) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, LAG, BMBx | IA & IIA: 5% (20/367) | na | MOPP (8%, 5/65) or E(A)BVD (5%, 15/302) then RT (89% IFRT) | In A(E)BVD subgroup (but not all patients), E disease was an independent predictor of poorer 10-year FFS. E disease status did not impact 10-year OS. | |

| 18 | 2005 | Gisselbrecht et al | 42 | nd | 1156 | 30 (14-69) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | nd | I-II: 8% (91/1156) | na | Per H8 (36/518) 3-6× MOPP/ABV, then IFRT or STNI; per H9 (55/638): CMT with 6× EBVP, 4-6× ABVD, or 4× BEACOPP, then IFRT | E-lesions associated with significantly worse OS at 42 months. Authors hypothesize E disease may be surrogate for bulky mediastinal disease | |

| 19 | 2007 | Gallamini et al | 43 | 2001-2006 | 216 (IV, 44) | 32 (14-72) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, LAG, FDG-PET | 6% (4 of 67) | 10% (7/70) | 24% (19/79) | na | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extranodal involvement. |

| 20 | 2011 | Wirth et al | 48 | 1999-2001 | 148 | 33 (18-75) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT, BMBx | I-II: 3% (5/148) | na | 3-4× ABVD, IFRT | Significant factor for worse OS and FFS at 5 years | |

| 21 | 2012 | Gobbi et al | 49§ | nd | 129 | 34 (20-48) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT with contrast neck/C/A/P | IA, IB, IIA + risk factors: 8% (10/129) | IIB, III, and IV taken together in analysis | 4-6× ABVD, IFRT | For early, unfavorable disease, presence of E-lesions was the only statistically important predictor of early treatment failure beyond relative tumor burden. | |

| 22 | 2013 | Song et al | 50 | 2006-2011 | 127 | 42 (18-78) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT neck/C/A/P, BMBx, FDG-PET/CT | I-II: 24% (30/127) | na | 4-6× ABVD and IF-RT or 6 ABVD | E-lesion not a significant factor for PFS nor OS at 45 months. | |

| 23 | 2014 | Laskar et al | 44§ | 2000-2008 | 151 | 20 (3-70) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT | IA: 0% (0/38) | IIA: 3% (3/96) | na | 4-6× ABVD and IFRT | E-lesions were a significant factor for worse 10-year PFS and OS among patients with early unfavorable disease. |

| IB: 0% (0/13) | IIB: 0% (0/4) | na | ||||||||||||

| 24 | 2018 | Gaudio et al | 46 | 2006-2017 | 384 (IV w/ bone involvement, 27/32; 85%). | 36 (15-83) | Ann Arbor | E-lesion vs stage IV sites nd | CXR, CT-CAP, FDG-PET/CT–total body, unilateral BMBx | I/II w/ bone involvement: 3% (1/32) | III w/ bone involvement: 12% (4/32) | ABVD w/wo RT | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extralymphatic involvement. | |

| 25 | 2018 | Gaudio et al | 45 | 2006-2016 | Stage I-II: 235 (III/IV, 106) | 36 (15-83) | Ann Arbor | E-lesion vs stage IV sites nd | CXR, CT-CAP, FDG-PET/CT–total body, unilateral BMBx | I/II: 3% (7/235) | III/VI | ABVD w/wo IFRT | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extralymphatic involvement. | |

| 26 | 2019 | Casasnovas et al | 47§| | 2011-2014 | 823 | 30 (16-30) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR; PET/CT head/neck/C/A/P; BMA | na | IIB: 11% (10/87) | na | Per AHL2011: 6× eBEACOPP vs 2× eBEACOPP then PET-driven BEACOPP and/or ABVD | nia |

| 27 | 2020 | Myint et al | 51 | 2005-2014 | 293 | 40 (18-85) | Ann Arbor | nd | nd | IA/IIA: 1% (2/293) | na | Chemotherapy alone vs CMT | E-lesion inclusion in multivariate survival modeling is not explicitly stated. | |

| 130 | 35 (18-88) | IB/IIB: 3% (4/130) | ||||||||||||

| 28 | 2021 | Picardi et al | 52 | 2017-2019 | 60 | 40 (18-70) | Ann Arbor classification with Lugano modification | nd | Same-day FDG- PET/CT, followed by FDG-PET/unenhanced MRI C/A/P; BMBx, U/S | 0% (0/8) | 1% (2/22) | na | 2-6× ABVD and IFRT (I/II) or residual mass RT | nia |

| 29 | 2021 | Kumar et al | 53§ | 2013-2019 | 117 | 32 (18-59) | Ann Arbor | Pericardial, chest wall, and sternum | PET | na | TG 1&2, II: 25% (15/59) | na | Brentiximab-vedotin + AVD ×4 cycles w/wo RT (TG 1&2 ISRT, TG3 CVRT) | No clear impact of E-lesions; 1 of 7 patients with primary refractory/relapsed disease had stage IIBXE disease. All patients had risk factors, with TG 2-4 (86% overall) having bulky (>7 cm) disease. |

| TG 3&4, I-II : 16% (9/56) | ||||||||||||||

| 30 | 2022 | Mauz-Korholz et al | 30 | 2007-2013 | TG2&3: 793 (IV, 494) | 14 (IQR, 12-16) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT with contrast neck/C/A/P (or MRI neck/A/P), FDG-PET | na | IIA: 97% (93/96) | IIIA: 16% (30/187) | Per EuroNet-PHL-C1: TG1: OEPA ×2; TG2: OEPA ×2 --> COPP or COPDAC ×2; TG3: OEPA ×2 --> COPP or COPDAC ×4; early response assessment-based w/wo IFRT w/wo residual RT boost | nia |

| na | IIB: 37% (114/308) | IIIB: 27% (54/202) | ||||||||||||

| 2023 | Mauz-Korholz et al | 31 | TG1: 713 | 14 (IQR, 12-16) | IA: 0% (0/40) | IIA:<1% (1/666) | IIIA: 0% (0/1) | |||||||

| IB: 0% (0/5) | IIB: 0% (0/1) | x | ||||||||||||

| 31 | 2021 | Borchmann et al | 54§ | 2012-2017 | 1096 | 31 (18-60) | Ann Arbor | nd | PET-CT | I-II with risk factor: 8% (89/1096) | na | Per HD17: 2× eBEACOPP + 2× ABVD; IFRT or PET-guided INRT | nia | |

| Study . | Year . | Author . | Reference . | Study period . | n∗ . | Median age, y (range) . | Staging criteria . | E-Lesion location (n) . | Staging tools . | Incidence of E-lesions by stage . | Treatment (E/total, % with E-lesion) . | Impact of E-lesions on prognosis, notable covariates . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I . | II . | III . | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1977 | Mill et al | 55 | 1968-1972 | 116 | nd | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR w/wo chest tomog, IVP, L/S, LAG, BMBx, lap (58%). | IA: 0% (0/23) | IIA: 4% (2/51) | IIIA: 4% (1/24) | RT (IFRT, EFRT, TNI) vs CMT | There were more relapses in E-lesion group (statistical significance, nd). |

| IB: 0% (0/2) | IIB: 19% (3/16) | na | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 1977 | Levi et al | 22† | 1968-1976 | 111 | (9-60) | Ann Arbor | Lung only (12), lung + other (2), thyroid (2), and subcutaneous (1) | CXR w/wo chest tomog (4%); EBx (8); lap (100%). | IA: 0% (0/9) | IIA: 12% (6/50) | IIIA: 18% (7/40) | Randomized: cobalt EFRT alone (16%, 11/67) vs CMT: LFRT followed by 3-6× MOPP (16%, 7/44) | E-lesions were associated with significantly more relapses, shorter remission duration, and worse OS in EFRT-only group but not in CMT group. Strong association between lung E-lesions, moderate to large mediastinal masses, and subsequent marginal recurrences. |

| na | IIB: 42% (5/12) | na | ||||||||||||

| 1982 | Wiernik and Slawson | 23‡ | 1966-1981 | 177 (62 unique) | nd | Ann Arbor | Majority pulmonary involvement by direct extension from MMT | Chest tomog; lap (100%). | I-III: 33/177 (19%) | Randomized to EFRT alone (19%, 20/106) vs CMT: RT and 6× MOPP (18%, 13/71) | ||||

| 3 | 1982 | Hoppe et al | 25‡ | 1968-1978 | 230 | nd | Ann Arbor | Lung (28), pleura (2), bone (6), pericardium (13), soft tissue (5), and myocardium (1) | CXR (90%); LAG, lap (100%). | I/II: 17% (40/230) | na | Randomized per H1, H2, H4, R1, K1, S1, S2, and S3: EFRT alone (8%, 9 of 109) vs CMT (26%, 8/121): IFRT (I-IIA), STNI (I-IIA, IIAE), or TLI (I-IIB, IIBE) then MOP(P) or PAVe | E-lesions were not a significant factor for OS or FFR within treatment groups. | |

| 1986 | Crnkovich et al | 26† | 1968-1982 | 126 | 26 | Ann Arbor | Lung (31), pericardium (14), pleura (11), bone (5), and other (6) | CXR, BMBx, LAG; most chest tomog/CT, lap (94%) | na | IIB: 33% (41/126) | na | TLI (18%, 13/73,); 18 pts CMT (53%, 28/53) most MOPP or PAVe | E-lesions were not a significant factor for 10-year OS and FFR between treatment groups. | |

| 4 | 1984 | Zagars and Rubin | 56 | 1969-1981 | 91 | 25 | Ann Arbor | Lung, pleura, pericardium, and thoracic wall | CXR, w/wo chest tomog/CT, LAG, w/wo lap with splenectomy | IA: nd | IIA:12% (6/51) | na | All RT (TNI or STNI), 8% CMT | E-lesions associated with significantly more relapses in stage IIA treated with RT alone. In 2 cases, mediastinal masses may have driven poor prognosis. In a small portion with CMT, E-lesions did not show negative prognostic implication. |

| 5 | 1985 | Zittoun et al | 34 | 1976-1981 | 335 | (15-74) | Ann Arbor | Mediastinal involvement | CXR, chest tomog, LAG, BMBx | I, II, and IIIA: 6% (20/335) | All CMT: 3×/6× MOPP and randomized to EFRT (4%, 7/166) vs IFRT (8%, 13/169) | Patients with stage IIE disease had significantly worse 5-year DFS than defined low-risk groups. | ||

| 6 | 1985 | Leslie et al | 35 | 1969-1980 | 307 | (3 to > 40) | Ann Arbor | Lung (13), pericard (5), chest wall (3), and other (4) | CXR w/wo chest tomog/CT, LAG, lap with splenectomy (100%) | IA-IIB supradiaphragmatic: 8% (25/307) | na | IA, IIA: RT alone; IB & IIB: RT alone or CMT with MOPP; RT mostly MPA | When analyzed by mediastinal size, E-lesions did not influence FFR or OS. Among patients with E-stage disease, 11 of 25 had B-symptoms and 13 of 25 had bulk disease. | |

| 7 | 1989 | Loeffler et al | 28†,§ | 1983-1988 | 89 | 28 (15-56) | Ann Arbor | Mostly massive lung involvement | CXR, abd CT & U/S, BMBx, SS; lap or liver bx/BMBx/LAG; optional: chest CT, L/S, skeletal XR | IA: 0% (0/1) | IIA: 28% (8 of 29); IIB: 24% (5/21) | IIIA: 8% (3/38) | Per HD1: (I-III with LMT, E-stage, and/or MSI): All CMT with 2× ABVD/COPP and EFRT or TNI; bulk RT boost; stage IIIA TNI | E-lesions had no prognostic significance for CR rate, FFTF, OS, or FFP. Six of the patients with stage IIAE disease and 5 of the patients with stage IIBE disease also had MLT. |

| 1997 | Loeffler et al | 27‡,§ | HD1: 1984-1988 | HD1 147 | (15-60) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, chest CT, abd CT and U of S, BMBx, liver biopsy, NM BS; optional studies: L/S, LAG, skeletal XR (lap recommended in HD1, but not HD5) | HD1, I-IIIA + risk factors: 41% (31/147) | Per HD1 & HD5: (I-III with LMT, E-stage, and/or MSI): all CMT with 2× ABVD/COPP and EFRT or TNI; bulk RT boost | Despite E-lesions not routinely irradiated (lung pleura), there were 100% local CR and no relapses after chemotherapy (median follow-up, 6.5 y). | |||

| HD5: 1988--1993 | HD5 111 | 31 (16-62) | HD5, I-IIIA + risk factors: 27% (30/111) | |||||||||||

| 8 | 1989 | Leopold et al | 36§ | 1969-1984 | 92 | (9-50) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, abd CT or LAG, BMBx, lap and splenectomy (74%, TG 1 and 2) | CS IA-IIB with LMA --> PS IA-IIIB: 29% (27/92) | TG 1: RT only with MPA, TNI, or whole-lung RT (17%, 6/38); TG 2&3: CMT with MOPP and IFRT, MRT, MPA, or TNI (39%, 21/54) | E-lesions had no significant effect on 12-year relapse rate or survival within treatment groups. | ||

| 9 | 1992 | Oberlin et al | 32 | 1982-1988 | 217 (IV, 21) | 10 (2-18) | Ann Arbor | Pleura (4), pericardium and pleura (1), thoracic wall (2), and lung (3). | CXR w/wo chest CT, LAG, BMBx | I-III: 5% (10/217) | TG1: ABVD only, TG2-4: CMT with ABVD w/wo MOPP, IF-RT w/wo LSF | Four patients with E-lesions (40%) had local relapses, (statistical significance, nd). Two of these had bulky disease. | ||

| 10 | 1999 | Shah et al | 37 | 1970-1995 | 106 | 14 (3-22) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C (61%) or CT A (78%) or CT P (73%), L/S (60%), LAG (50%), NM BS (34%), NI (84%), lap (60%), w/wo BMBx | Supradiaphagmatic I/II: 3% (3/106) | na | RT, IFRT, mantle only, TNI, STNI | E-lesions had no significant influence on relapse rate, OS, or EFS. | |

| 11 | 2000 | Franklin et al | 18§ | 1988-1994 | 712 | (15-75) | Ann Arbor | nd | nd | I-IIIA: 12% (85 of 712) | Per HD5: CMT with COPP/ABVD or COPP/ABV/IMEP, followed by EFRT, bulk RT boost | Patients with E-lesions, especially IIBE and IIIE, had a poor prognosis at 5 years. E-lesions were a significant poor prognostic factor beyond IPS. | ||

| na | IIB-IIIA: 5% (35/712) | |||||||||||||

| 2002 | Sieber et al | 29‡,§ | 1988-1993 | 973 | 31 (16-74) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, BMBx, liver bx | I, II, and IIIA: 12% (113/973) | 7-year FFTF and CR rate significantly worse in both treatment arms. | ||||

| 12 | 2001 | Ruhl et al | 33 | 1995-2000 | 730 (IV, 100) | 14 (maximum 18) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | Pleura, pericardium, and anterior thoracic wall | CXR, chest CT, abd CT/MRI; US th/ abd/ LN; w/wo neck CT/MRI, NM BS, BMBx, lap/liver bx | 0% (0/58) | IIA: 27% (100/365) | IIIA: 33% (25/75) | Per GPOH-HD 95: all 2× OEPA/OPPA, w/wo 2× or 4× COPP; response-adapted IFRT | E-lesions were a significant risk factor for both progressive disease and relapse. |

| na | IIB: 53% (66/125) | IIIB: 27%(25/91) | ||||||||||||

| 13 | 2002 | Dieckmann et al | 15 | 1990-1995 | 518 (IV, 60), precentral review | 12 (2-17) | Ann Arbor | Pericardium, lung, chest wall, and pleura. | CXR, CT C/A/P, U/S (neck, axilla, abd, pelvis), w/wo lap, w/wo BMBx | IA: 1% (1/98); IB: 0% (0/7) | IIA: 9% (20/218); IIB: 18% (14/78) | IIIA: 12% (7/59); IIIB: 15% (9 of 58) | Per GPOH-HD-90: TG1 (I/IIA) 2× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); TG2 (IIB/IIIA/IE/IIEA); 4× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); TG3 (IIIB/IV/IIEB/IIIE) 6× OPPA (females) or OEPA (males); all groups received local RT to initially involved areas (25 Gy TG 1&2; 20 Gy TG3; w/wo 5-10 Gy boost) | nia |

| 494 (IV, 84), postcentral review | IA: 0% (0/89); IB: 0% (0/5) | IIA: 15% (33/214); IIB: 37% (29/78) | IIIA: 24% (13/55); IIIB: 21% (11/53) | |||||||||||

| 14 | 2003 | Glimelius et al | 38 | 1985-1994 | 99 | 33 (17-59) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, abd US, BMBx | na | IIB: 11% (11/99) | na | CT 6-8× MOPP/ABVD, RT | Not significant in 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival |

| 15 | 2003 | Hodgson et al | 39 | 1981-1996 | 324 | 29 (15-78) | Ann Arbor | Lung or chest wall. | Chest CT | I-II: 12% of (40/324) lung invasion | na | All CMT | 5-year OS: no significant effect | |

| I-II: 7% (22/324) of chest-wall invasion | Chest wall significantly worse; 5-year CSS and DFS: lung extension no significant effect | |||||||||||||

| 16 | 2004 | Hudson et al | 40§ | 1993-2000 | 115 (IV, 44) | 15 (2-19) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT with contrast neck/C/A/P (or MRI for A/P) | I-II with risk factors or III: 10% (11/115) | na | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extranodal involvement. | ||

| 17 | 2004 | Vassilakopoulos et al | 41 | 1980-2001 | 367 | 30 (14-82) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, LAG, BMBx | IA & IIA: 5% (20/367) | na | MOPP (8%, 5/65) or E(A)BVD (5%, 15/302) then RT (89% IFRT) | In A(E)BVD subgroup (but not all patients), E disease was an independent predictor of poorer 10-year FFS. E disease status did not impact 10-year OS. | |

| 18 | 2005 | Gisselbrecht et al | 42 | nd | 1156 | 30 (14-69) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | nd | I-II: 8% (91/1156) | na | Per H8 (36/518) 3-6× MOPP/ABV, then IFRT or STNI; per H9 (55/638): CMT with 6× EBVP, 4-6× ABVD, or 4× BEACOPP, then IFRT | E-lesions associated with significantly worse OS at 42 months. Authors hypothesize E disease may be surrogate for bulky mediastinal disease | |

| 19 | 2007 | Gallamini et al | 43 | 2001-2006 | 216 (IV, 44) | 32 (14-72) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CXR, CT C/A/P, LAG, FDG-PET | 6% (4 of 67) | 10% (7/70) | 24% (19/79) | na | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extranodal involvement. |

| 20 | 2011 | Wirth et al | 48 | 1999-2001 | 148 | 33 (18-75) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT, BMBx | I-II: 3% (5/148) | na | 3-4× ABVD, IFRT | Significant factor for worse OS and FFS at 5 years | |

| 21 | 2012 | Gobbi et al | 49§ | nd | 129 | 34 (20-48) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT with contrast neck/C/A/P | IA, IB, IIA + risk factors: 8% (10/129) | IIB, III, and IV taken together in analysis | 4-6× ABVD, IFRT | For early, unfavorable disease, presence of E-lesions was the only statistically important predictor of early treatment failure beyond relative tumor burden. | |

| 22 | 2013 | Song et al | 50 | 2006-2011 | 127 | 42 (18-78) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT neck/C/A/P, BMBx, FDG-PET/CT | I-II: 24% (30/127) | na | 4-6× ABVD and IF-RT or 6 ABVD | E-lesion not a significant factor for PFS nor OS at 45 months. | |

| 23 | 2014 | Laskar et al | 44§ | 2000-2008 | 151 | 20 (3-70) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT | IA: 0% (0/38) | IIA: 3% (3/96) | na | 4-6× ABVD and IFRT | E-lesions were a significant factor for worse 10-year PFS and OS among patients with early unfavorable disease. |

| IB: 0% (0/13) | IIB: 0% (0/4) | na | ||||||||||||

| 24 | 2018 | Gaudio et al | 46 | 2006-2017 | 384 (IV w/ bone involvement, 27/32; 85%). | 36 (15-83) | Ann Arbor | E-lesion vs stage IV sites nd | CXR, CT-CAP, FDG-PET/CT–total body, unilateral BMBx | I/II w/ bone involvement: 3% (1/32) | III w/ bone involvement: 12% (4/32) | ABVD w/wo RT | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extralymphatic involvement. | |

| 25 | 2018 | Gaudio et al | 45 | 2006-2016 | Stage I-II: 235 (III/IV, 106) | 36 (15-83) | Ann Arbor | E-lesion vs stage IV sites nd | CXR, CT-CAP, FDG-PET/CT–total body, unilateral BMBx | I/II: 3% (7/235) | III/VI | ABVD w/wo IFRT | E-lesions were not distinguished from stage IV disease with analysis regarding extralymphatic involvement. | |

| 26 | 2019 | Casasnovas et al | 47§| | 2011-2014 | 823 | 30 (16-30) | Ann Arbor | nd | CXR; PET/CT head/neck/C/A/P; BMA | na | IIB: 11% (10/87) | na | Per AHL2011: 6× eBEACOPP vs 2× eBEACOPP then PET-driven BEACOPP and/or ABVD | nia |

| 27 | 2020 | Myint et al | 51 | 2005-2014 | 293 | 40 (18-85) | Ann Arbor | nd | nd | IA/IIA: 1% (2/293) | na | Chemotherapy alone vs CMT | E-lesion inclusion in multivariate survival modeling is not explicitly stated. | |

| 130 | 35 (18-88) | IB/IIB: 3% (4/130) | ||||||||||||

| 28 | 2021 | Picardi et al | 52 | 2017-2019 | 60 | 40 (18-70) | Ann Arbor classification with Lugano modification | nd | Same-day FDG- PET/CT, followed by FDG-PET/unenhanced MRI C/A/P; BMBx, U/S | 0% (0/8) | 1% (2/22) | na | 2-6× ABVD and IFRT (I/II) or residual mass RT | nia |

| 29 | 2021 | Kumar et al | 53§ | 2013-2019 | 117 | 32 (18-59) | Ann Arbor | Pericardial, chest wall, and sternum | PET | na | TG 1&2, II: 25% (15/59) | na | Brentiximab-vedotin + AVD ×4 cycles w/wo RT (TG 1&2 ISRT, TG3 CVRT) | No clear impact of E-lesions; 1 of 7 patients with primary refractory/relapsed disease had stage IIBXE disease. All patients had risk factors, with TG 2-4 (86% overall) having bulky (>7 cm) disease. |

| TG 3&4, I-II : 16% (9/56) | ||||||||||||||

| 30 | 2022 | Mauz-Korholz et al | 30 | 2007-2013 | TG2&3: 793 (IV, 494) | 14 (IQR, 12-16) | Cotswolds revision of Ann Arbor | nd | CT with contrast neck/C/A/P (or MRI neck/A/P), FDG-PET | na | IIA: 97% (93/96) | IIIA: 16% (30/187) | Per EuroNet-PHL-C1: TG1: OEPA ×2; TG2: OEPA ×2 --> COPP or COPDAC ×2; TG3: OEPA ×2 --> COPP or COPDAC ×4; early response assessment-based w/wo IFRT w/wo residual RT boost | nia |

| na | IIB: 37% (114/308) | IIIB: 27% (54/202) | ||||||||||||

| 2023 | Mauz-Korholz et al | 31 | TG1: 713 | 14 (IQR, 12-16) | IA: 0% (0/40) | IIA:<1% (1/666) | IIIA: 0% (0/1) | |||||||

| IB: 0% (0/5) | IIB: 0% (0/1) | x | ||||||||||||

| 31 | 2021 | Borchmann et al | 54§ | 2012-2017 | 1096 | 31 (18-60) | Ann Arbor | nd | PET-CT | I-II with risk factor: 8% (89/1096) | na | Per HD17: 2× eBEACOPP + 2× ABVD; IFRT or PET-guided INRT | nia | |

abd, abdomen; ABVD, adriamycin/bleomycin/vinblastine/dacarbazine; BMA, bone marrow aspirate; BMBx, bone marrow biopsy; Bx, biopsy; C/A/P, chest/abdomen/pelvis; CMT, combined modality therapy; COPP, cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednison, procabazin; COPDAC, cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednison, dacarbazin; CR, complete remission; CS, clinical stage; CT, computed tomography; CVRT, consolidation-volume radiotherapy; CXR, chest X-ray; DFS, disease-free survival; eBEACOPP, escalated dose etoposide/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin and regular doses bleomycin/vincristine/procarbazine/prednisone; EBx, E-lesion biopsy; EFRT, extended field radiotherapy; EFS, event-free survival; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose, FFP, failure free progression; FFR, freedom from first relapse; FFS, freedom from progression; FFTF, freedom from treatment failure; HD, Hodgkin disease; IFRT, involved field radiotherapy; ISRT, involved site radiotherapy; IPS, international prognostic score; IQR, interquartile range; IVP, intravenous pyelogram; LAG, bipedal lymphangiography; lap, staging laparotomy; LFRT, limited field radiotherapy; LMA, large mediastinal adenopathy; LMT, large mediastinal mass; LN, lymph nodes; L/S, liver/spleen scintiscan; LSF, lumbo-splenic field radiotherapy; MMT, massive mediastinal tumor; MOPP, mustargen/oncovin/procarbazine/prednisone; MPA, mantle and para-aortic splenic pedicle radiotherapy; MRT, mantle radiation therapy; MSI, massive spleen involvement; n, number of cases; na, not applicable; nd, not defined; nia, not included in analysis; NM BS, nuclear medicine bone scan; OEPA, oncovin, etoposide, prednison, anthracyclin (doxorubicin); OPPA, oncovin, procarbazin, prednison, anthracyclin (doxorubicin); PAVe, procarbazine/l-phenylalamine mustard/vinblastine; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, pathologic stage; Ref, reference; RT, radiotherapy; SS, skeletal scan; STNI, subtotal nodal irradiation; TG, treatment group; th, thorax; TLI, total lymphoid irradiation; TNI, total nodal irradiation; tomog, tomography; U/S, ultrasound; x, times; XR, X-ray; and w/wo, with or without.

Patients with stage IV HL were excluded in this number.

Because there were overlapping study populations, these data were used for stage-specific incidence calculation.

Because there were overlapping study populations, these data were used for overall incidence calculation.

This study used elevated risk–based criteria for inclusion.

The first 2 articles with overlapping populations were by Levi et al22 and Wiernik and Slawson.23 Wiernik and Slawson reported a follow-up of the patient population described by Levi et al and also added unique patients to the group. The only stage-specific E-lesion incidence data available was from the Levi et al study. To avoid double counting patients, only the larger population reported by Wiernik was used for the overall incidence calculation. Both articles were used in the prognosis analysis because they provided unique outcomes analyses. Another article by Levi24 was excluded because it did not include unique E-lesion incidence or prognostic data.

A second instance of overlapping populations was encountered when Hoppe25 and Crnkovich26 described Stanford HL outcomes during a similar time period. The Hoppe article reported on patients with stage I-II HL. The Crnkovich article appeared to include a longer-term follow-up of a subset (stage IIB) of the same patients. The only stage-specific E-lesion incidence data available was from the Crnkovich article. To avoid double counting patients, only the larger population reported by Hoppe was used for the overall incidence calculation. Both articles were used in the prognosis analysis because they provided unique outcomes analyses.

A third set of overlapping populations studied by Loeffler et al27,28 reported unique prognostic data from patients treated on the German HD1 study. The only stage-specific data available were from the 1989 article. To avoid double counting of patients, we used the 1997 article (with the larger population) in the overall incidence calculation.

The final set of overlapping populations were patients treated on the German HD5 treatment protocol described by Franklin18 and Sieber.29 Both articles were included because they each described discrete prognostic data. To avoid double counting patients, only the larger population reported by Sieber was used for the overall incidence calculation.

Table 3 denotes which of the overlapping studies were used for incidence calculations. Because the presence of E-lesions was used to determine EuroNet PHL-C1 treatment groups, the stage-specific incidence data from the separate articles30,31 were interpreted as a single study population. All articles included in our final analysis were published between 1977 and 2022.

Participant characteristics

In the 36 articles analyzed, 12 640 patients (aged 2-88 years) with stage I-III HL were included. Five articles included solely pediatric patients (aged 0-18 years),15,30-33 19 articles included children and adults,18,22,27-29,34-47 7 included only adults,48-54 and 5 articles23,25,26,55,56 provided limited information about patient age.

Definition of E-Lesions

We observed that 26 articles used the Ann Arbor criteria for staging classification,12,15,18,22,23,25-29,32,34-41,45-47,51,53-56 9 articles used the Cotswolds revision of the Ann Arbor staging classification,30,33,42-44,48-50 and 1 study used the Lugano criteria.52 Fourteen studies provided some description of E-lesion location.12,22,23,25,26,28,32-35,39,45,46,53,56

Diagnostic tools

A wide variety of imaging modalities were used in these studies because of the evolution of imaging technology over time. Studies used a combination of X-ray imaging, CT (or focal plane tomography), nuclear medicine (liver spleen scan, positron emission tomography [PET], and bone scan), ultrasound, and MRI, in addition to surgical sampling (biopsies, laparotomies, and splenectomies) for staging. Several studies in our analysis concluded that CT scanning was more sensitive than X-ray imaging for the detection of E-lesions of the lung parenchyma, pleura, pericardium, and chest wall.57-61 Gaudio et al noted more extranodal localizations were found with the use of PET/CT than with contrast-enhanced CT for staging.45 One pediatric article reported their findings with full-body MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging for staging in 50 pediatric patients with HL (aged 5-19 years) enrolled on Euronet PHL-C1 or PHL-LP1 trials and concluded that the technology was not acceptably equivalent to PET-CT for staging purposes (Ann Arbor staging concordant in 78%, 39/50),62 including at extranodal sites (28% discordance rate; 95% confidence interval exact, 17.8-40.3).62

Incidence of E-lesions by stage

In the 36 articles analyzed, 1330 of the 11 602 unique patients (12.4%) had an E-lesion (results summarized in Table 4). Sixteen articles15,22,26,28,30,31,33,38,43,44,46,47,52,53,55,56 encompassing 3888 patients provided stage-specific E-lesion incidence data. E-lesions were rarely present in stage I disease, affecting 1.1% (4/365) of patients (range, 0%-6%). Available data did not show a difference in incidence between IA and IB subgroups. E-lesions were similarly prevalent in stage II and III disease, affecting 21.2% (560/2646) of patients (range, 0%-53%) and 21.9% (192/877) of patients (range, 4%-33%), respectively. Overall, there were notably more E-lesions in patients with stage IIB disease (32.4% [284/877]; range, 0%-53%) than in those with stage IIA disease (15.6% [252/1618]; range, 3%-28%). A similar relationship was seen with more E-lesions in patients with stage IIIB disease (26.0% [90/346]; range, 21%-27%) than in those with stage IIIA disease (18.8% [79/420]; range, 4%-33%).

Summary of incidence of E-lesions by stage

| Stage . | n (E/total) . | Percentage . | Range (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 4/365 | 1.1 | 0-6 |

| IA | 0/258 | 0 | 0-0 |

| IB | 0/32 | 0 | 0-0 |

| II | 560/2646 | 21.2 | 0-53 |

| IIA | 252/1618 | 15.6 | 3-28 |

| IIB | 284/877 | 32.4 | 0-53 |

| III | 192/877 | 21.9 | 4-33 |

| IIIA | 79/420 | 18.8 | 4-33 |

| IIIB | 90/346 | 26.0 | 21-27 |

| Stage . | n (E/total) . | Percentage . | Range (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 4/365 | 1.1 | 0-6 |

| IA | 0/258 | 0 | 0-0 |

| IB | 0/32 | 0 | 0-0 |

| II | 560/2646 | 21.2 | 0-53 |

| IIA | 252/1618 | 15.6 | 3-28 |

| IIB | 284/877 | 32.4 | 0-53 |

| III | 192/877 | 21.9 | 4-33 |

| IIIA | 79/420 | 18.8 | 4-33 |

| IIIB | 90/346 | 26.0 | 21-27 |

| When high risk–based studies were excluded: . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage . | n (E/total) . | Percentage . | Range (%) . |

| I | 4/313 | 1.3 | 0-6 |

| IA | 0/219 | 0 | 0-0 |

| IB | 0/19 | 0 | 0-0 |

| II | 529/2437 | 21.7 | 4-53 |

| IIA | 241/1493 | 16.1 | 4-27 |

| IIB | 279/852 | 32.7 | 11-53 |

| III | 189/839 | 22.5 | 4-33 |

| IIIA | 76/382 | 19.9 | 4-33 |

| IIIB | 90/346 | 26.0 | 21-27 |

| When high risk–based studies were excluded: . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage . | n (E/total) . | Percentage . | Range (%) . |

| I | 4/313 | 1.3 | 0-6 |

| IA | 0/219 | 0 | 0-0 |

| IB | 0/19 | 0 | 0-0 |

| II | 529/2437 | 21.7 | 4-53 |

| IIA | 241/1493 | 16.1 | 4-27 |

| IIB | 279/852 | 32.7 | 11-53 |

| III | 189/839 | 22.5 | 4-33 |

| IIIA | 76/382 | 19.9 | 4-33 |

| IIIB | 90/346 | 26.0 | 21-27 |

Nine studies18,27,36,40,44,47,49,53,54 used risk-based inclusion criteria, including a combination of stage, bulk disease (mediastinal or other sites), extranodal disease, B-symptoms, massive spleen involvement, or GHSG unfavorable early-stage disease. When these studies were excluded, the overall and stage-specific incidence of E-lesions were relatively unchanged (stage I-III: 12.5% [982/7848]; stage I: 1.3%, stage II: 21.7%, stage III: 22.5%).

Treatment and prognosis

Twenty-two articles, encompassing 5836 patients, examined the prognostic implication of E-lesions (Table 5). Eight articles18,29,33,34,42,44,48,49 (3622 patients) found the presence of E-lesions to be predictive of poorer outcomes, including relapse and survival metrics. All patients in this subset received CMT, except patients in 2 studies33,42 in which response-adapted radiotherapy was also used. The interim report of the prospective, nonrandomized German Society of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology Hodgkin Lymphoma Trial 95 examining response-adapted involved field radiotherapy in pediatric early-stage HL found E-lesions to be an independent risk factor for both progressive disease (P < .002) and relapse (P < .002) at a median follow-up of 38 months.33 Two articles18,29 similarly commented on the association of E-lesions and poor relapse outcomes in the HD5 trial, which evaluated different CMT regimens in patients with stage I-II HL with GHSG risk factors, or with stage III HL. E-lesion also trended toward providing additional prognostic value beyond the International Prognostic Score for disease-free survival, reaching statistical significance for stage IIB-IIIA HL; the authors speculate this may be related to misclassification between the sometimes subtle distinction between E-lesion and stage IV disease.18 Another study comparing cooperative group risk criteria used pooled outcomes from H8 and H9 randomized trials found E-lesions to be associated with significantly worse overall survival at 42 months in patients with stage I-II disease largely treated with CMT (multivariate, stage–adjusted prognostic index, relative risk [RR], 1.2; P = .008), but the authors hypothesized that bulky mediastinal disease may be the driver of the poor outcomes in these patients.42

Studies grouped by E-lesion prognostic influence

| No . | Year . | Author . | Reference . | Impact of E-lesions on prognosis and noted covariates . | Treatment . | OS . | DFS/PFS/FFTF . | Relapse rate . | CR/duration/other outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Studies concluding E-lesions are a poor prognostic factor under nuanced circumstances | |||||||||

| 2 | 1977 | Levi et al | 22 | E-lesions were associated with significantly more relapses, shorter remission duration, and worse OS in EFRT-only group but not CMT group. Strong association between lung E-lesions, moderate to large mediastinal masses, and subsequent marginal recurrences. | RT | 4-year OS worse with E-lesion RT-only group: nodal ∼87% vs E-lesion ∼56% (P ≤ .01) | Significantly shorter remission duration for the patients with “E”-stage disease when extended field irradiation was the initial therapy (P < .002) | Relapse after 5 years: 29% nodal disease (14/48) vs 82% with E-lesions (9/11) | 3-year CR duration: nodal ∼71% vs E-lesion ∼18% |

| CMT | 5-year OS not significantly different with CMT: nodal ∼100% vs E-lesion ∼97% (P > .10) | No significant difference between the 2 patient groups when initial therapy was CMT (P > .35) | Relapse after 5 years: nodal disease (6%, 2/36) vs E-lesions (14%, 1/7) | 5-year CR duration: nodal ∼95% vs E-lesion ∼86% | |||||

| 1982 | Wiernik and Slawson | 23 | RT | 12-year OS: nodal ∼90% vs E-lesion ∼60% (P < .03) | 12-year DFS of original 115 pts: Nodal 78% vs E-lesion 28% (P = .002) | nd | 12-year CR duration: Nodal ∼83% vs E-lesion ∼38% (p = 0.001) | ||

| CMT | 12-year OS: nodal ∼98% vs E-lesion ∼93% (P > .4) | 12-year DFS of original 115 pts: nodal 84% vs E-lesion 94% (P = .002) | nd | 12-year CR duration: nodal ∼97% vs E-lesion ∼90% (P > .3) | |||||

| 4 | 1984 | Zagars and Rubin | 56 | E-lesions associated with significantly more relapses in stage IIA treated with RT alone. In 2 cases, mediastinal masses may have driven poor prognosis. In small portion with CMT, E-lesions did not show negative prognostic implication. | RT vs CMT | nd | nd | Significantly more relapses, P < .05 | nd |

| 15 | 2003 | Hodgson et al | 39 | 5-year OS: no significant effect | CMT | nd | 5-year DFS: no E-lesion (84%) vs chest wall (59%) (P = .016) | nd | 5-year cause-specific survival: No E (94%) vs chest wall (86%) (P = .009) |

| Chest wall significantly worse; 5-year CSS and DFS: lung extension no significant effect | CMT | 5-year OS: 90% no E-lesion, 82% chest-wall invasion (P = .095), 88% lung invasion (P = .386) | 5-year DFS: no E (84%) vs lung invasion (80%) (P = .47) | nd | 5-year cause-specific survival: No E (94%) vs lung invasion 92% (P = .25) | ||||

| 17 | 2004 | Vassilakopoulos et al | 41 | In A(E)BVD subgroup (but not all patients), E disease was an independent predictor of poorer 10-year FFS. E disease status did not impact 10-year OS. | CMT | nd | 10-year FFS: A(E)BVD subgroup, no (87%) vs (73%) (P = .03) | nd | FFTF in patients who achieved CR, CR, or VGPR and received low-dose RT, E-lesion prognostic factor P < .001 in all treatment groups. |

| CMT | 10-year OS: all patients, no E (86%) vs E (94%) (P = .30); A(E)BVD only, no E (93%) vs E (100%) (P = .37) | 10-year FFS: all patients, no E (85%) vs E (75%) (P = .11) | nd | nd | |||||

| B. Studies concluding E-lesions are not a prognostic factor | |||||||||

| 3 | 1982 | Hoppe et al | 25 | E-lesions were not a significant factor for OS or FFR within treatment groups. | RT | 5-year OS: E-lesions, 100% vs all patients, 96% | 5-year FFR: E-lesions, 78% vs all patients, 79% | nd | nd |

| CMT | 5-years OS: E-lesions, 88% vs all patients, 92% | 5-year FFR: E-lesions, 90% vs all patients, 87% | nd | nd | |||||

| 1986 | Crnkovich et al | 26 | E-lesions were not a significant factor for 10-year OS and FFR between treatment groups. | RT | 10-year OS: RT arm, 87% vs all patients, 87% | 10-year FFR: RT arm, 70% vs all patients, 71% | nd | nd | |

| CMT | 10-year OS: E-lesions, 72% vs all patients, 74% | 10-year FFR: CMT arm, 71% vs all patients, 79% | nd | nd | |||||

| 6 | 1985 | Leslie et al | 35 | When analyzed by mediastinal size, E-lesions did not influence FFR or OS. Among patients with E-stage disease, 11 of 25 had B-symptoms and 13 of 25 had bulk disease. | RT or CMT | 10-year OS for large mediastinal adenopathy with E vs without E: 85% vs 81% | 10-year FFR for large mediastinal adenopathy with E vs without E: 62% vs 58% | nd | nd |

| 10-year OS for small mediastinum with E vs without E: 80 vs 84% | 10-year FFR for small mediastinum with E vs without E: 85% vs 81% | nd | nd | ||||||

| 7 | 1989 | Loeffler et al | 28∗ | E-lesions had no prognostic significance for CR rate, FFTF, OS, or FFP. Six of the patients with stage IIAE disease and 5 of the patients with stage IIBE disease also had MLT. | CMT | 3-year OS: no influence of E-lesions | FFTF: all patients vs E, 20% vs 25%, not significant | nd | CR rate: all patients vs E, 83% vs 81% |

| 1997 | Loeffler et al | 27∗ | Despite E-lesions not routinely irradiated (lung and pleura), there were 100% local CR and no relapses after chemotherapy (median follow-up, 6.5 y). | CMT | nd | nd | No relapses after chemotherapy; median follow-up, 6.5 y | 100% local CR; median follow-up, 6.5 y | |

| 8 | 1989 | Leopold et al | 36∗ | E-lesions had no significant effect on 12-year relapse rate or survival within treatment groups. | RT | 12-year OS: no effect in different treatment groups | nd | Relapse rate not significantly different in treatment groups | nd |

| CMT | 12-year OS: no effect in different treatment groups | nd | Relapse rate not significantly different in treatment groups | nd | |||||

| 10 | 1999 | Shah et al | 37 | E-lesions had no significant influence on relapse rate, OS, or EFS. | RT | 10-year OS: no influence | 10-year EFS: no influence | nd | nd |

| 14 | 2003 | Glimelius et al | 38 | Not significant in 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival | CMT | nd | 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival not significant | nd | nd |

| 22 | 2013 | Song et al | 50 | E-lesion not a significant factor for PFS and OS at 45 months. | All chemo, some CMT | Hazard ratio for OS if E-lesion: 2.581; 95% CI, 0.916-7.273; P = .073 | Hazard ratio for PFS if E-lesion: 1.762; 95% CI, 0.661-4.698; P = .258 | nd | nd |

| C. Studies concluding E-lesions are a poor prognostic factor | |||||||||

| 5 | 1985 | Zittoun et al | 34 | Patients with stage IIE disease had significantly worse 5-year DFS than defined low-risk groups. | CMT | nd | 5-year DFS: significantly worse for patients with stage IIE (significance not provided). | nd | nd |

| 11 | 2000 | Franklin et al | 18∗ | Patients with E-lesions, especially IIBE and IIIE, had a poor prognosis at 5 years. E-lesions were a significant poor prognostic factor beyond IPS. | CMT | nd | DFS: Cox regression with IPS and additional factors after 5 years: stage IIBE and IIIE significant in addition to IPS (P = .017), hazard ratio: 2.62; all E-lesions HR 1.54; P = .086 | nd | nd |

| 2002 | Sieber et al | 29∗ | 7-year FFTF and CR rate significantly worse in both treatment arms. | CMT | nd | 7-year FFTF: significantly worse (P = .015) | nd | CR duration significantly worse COPP/ABVD arm, 86% vs 94% (P = .011) and COPP/ABV/IMEP arm 82% vs 86% (P ≤ .001) | |

| 12 | 2001 | Ruhl et al | 33 | E-lesions were a significant risk factor for both progressive disease and relapse. | All chemo, some CMT | nd | Risk factor for progressive disease (P ≤ .002); median follow-up time, 38 mo | Risk factor for relapse (P < .002); median follow-up time, 38 mo | nd |

| 18 | 2005 | Gisselbrecht et al | 42 | E-lesions associated with significantly worse OS at 42 mo. Authors hypothesize E disease may be surrogate for bulky mediastinal disease. | All chemo, most CMT | Multivariate analysis stage–adjusted prognostic index 42-mo OS RR: 1.2 (P = .008) | nd | nd | nd |

| 20 | 2011 | Wirth et al | 48 | Significant factor for worse OS and FFS at 5 y | CMT | 5-year OS: no E vs E, 97% (95% CI, 93-100) vs 67% (95% CI, 20-90); P = .0005. | 5-year PFS: no E vs E: 92% (95% CI, 86-96) vs 50% (95% CI, 11-80); P = .0002) | nd | Remained significant factor in multivariate analysis. |

| 21 | 2012 | Gobbi et al | 49∗ | For early, unfavorable disease, presence of E-lesions was the only statistically important predictor of early treatment failure beyond relative tumor burden. | CMT | nd | nd | nd | Early treatment failure predictor in addition to relative tumor burden: E-lesions coef: 0.846; risk, 2.329; P = .0329 |

| 23 | 2014 | Laskar et al | 44∗ | Significant factor for worse 10-year PFS and OS | CMT | 10-year OS: no E (96%) vs E (0%) (P = .01) | 10-year PFS: E significantly worse (P = .037) | nd | nd |

| No . | Year . | Author . | Reference . | Impact of E-lesions on prognosis and noted covariates . | Treatment . | OS . | DFS/PFS/FFTF . | Relapse rate . | CR/duration/other outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Studies concluding E-lesions are a poor prognostic factor under nuanced circumstances | |||||||||

| 2 | 1977 | Levi et al | 22 | E-lesions were associated with significantly more relapses, shorter remission duration, and worse OS in EFRT-only group but not CMT group. Strong association between lung E-lesions, moderate to large mediastinal masses, and subsequent marginal recurrences. | RT | 4-year OS worse with E-lesion RT-only group: nodal ∼87% vs E-lesion ∼56% (P ≤ .01) | Significantly shorter remission duration for the patients with “E”-stage disease when extended field irradiation was the initial therapy (P < .002) | Relapse after 5 years: 29% nodal disease (14/48) vs 82% with E-lesions (9/11) | 3-year CR duration: nodal ∼71% vs E-lesion ∼18% |

| CMT | 5-year OS not significantly different with CMT: nodal ∼100% vs E-lesion ∼97% (P > .10) | No significant difference between the 2 patient groups when initial therapy was CMT (P > .35) | Relapse after 5 years: nodal disease (6%, 2/36) vs E-lesions (14%, 1/7) | 5-year CR duration: nodal ∼95% vs E-lesion ∼86% | |||||

| 1982 | Wiernik and Slawson | 23 | RT | 12-year OS: nodal ∼90% vs E-lesion ∼60% (P < .03) | 12-year DFS of original 115 pts: Nodal 78% vs E-lesion 28% (P = .002) | nd | 12-year CR duration: Nodal ∼83% vs E-lesion ∼38% (p = 0.001) | ||

| CMT | 12-year OS: nodal ∼98% vs E-lesion ∼93% (P > .4) | 12-year DFS of original 115 pts: nodal 84% vs E-lesion 94% (P = .002) | nd | 12-year CR duration: nodal ∼97% vs E-lesion ∼90% (P > .3) | |||||

| 4 | 1984 | Zagars and Rubin | 56 | E-lesions associated with significantly more relapses in stage IIA treated with RT alone. In 2 cases, mediastinal masses may have driven poor prognosis. In small portion with CMT, E-lesions did not show negative prognostic implication. | RT vs CMT | nd | nd | Significantly more relapses, P < .05 | nd |

| 15 | 2003 | Hodgson et al | 39 | 5-year OS: no significant effect | CMT | nd | 5-year DFS: no E-lesion (84%) vs chest wall (59%) (P = .016) | nd | 5-year cause-specific survival: No E (94%) vs chest wall (86%) (P = .009) |

| Chest wall significantly worse; 5-year CSS and DFS: lung extension no significant effect | CMT | 5-year OS: 90% no E-lesion, 82% chest-wall invasion (P = .095), 88% lung invasion (P = .386) | 5-year DFS: no E (84%) vs lung invasion (80%) (P = .47) | nd | 5-year cause-specific survival: No E (94%) vs lung invasion 92% (P = .25) | ||||

| 17 | 2004 | Vassilakopoulos et al | 41 | In A(E)BVD subgroup (but not all patients), E disease was an independent predictor of poorer 10-year FFS. E disease status did not impact 10-year OS. | CMT | nd | 10-year FFS: A(E)BVD subgroup, no (87%) vs (73%) (P = .03) | nd | FFTF in patients who achieved CR, CR, or VGPR and received low-dose RT, E-lesion prognostic factor P < .001 in all treatment groups. |

| CMT | 10-year OS: all patients, no E (86%) vs E (94%) (P = .30); A(E)BVD only, no E (93%) vs E (100%) (P = .37) | 10-year FFS: all patients, no E (85%) vs E (75%) (P = .11) | nd | nd | |||||

| B. Studies concluding E-lesions are not a prognostic factor | |||||||||

| 3 | 1982 | Hoppe et al | 25 | E-lesions were not a significant factor for OS or FFR within treatment groups. | RT | 5-year OS: E-lesions, 100% vs all patients, 96% | 5-year FFR: E-lesions, 78% vs all patients, 79% | nd | nd |

| CMT | 5-years OS: E-lesions, 88% vs all patients, 92% | 5-year FFR: E-lesions, 90% vs all patients, 87% | nd | nd | |||||

| 1986 | Crnkovich et al | 26 | E-lesions were not a significant factor for 10-year OS and FFR between treatment groups. | RT | 10-year OS: RT arm, 87% vs all patients, 87% | 10-year FFR: RT arm, 70% vs all patients, 71% | nd | nd | |

| CMT | 10-year OS: E-lesions, 72% vs all patients, 74% | 10-year FFR: CMT arm, 71% vs all patients, 79% | nd | nd | |||||

| 6 | 1985 | Leslie et al | 35 | When analyzed by mediastinal size, E-lesions did not influence FFR or OS. Among patients with E-stage disease, 11 of 25 had B-symptoms and 13 of 25 had bulk disease. | RT or CMT | 10-year OS for large mediastinal adenopathy with E vs without E: 85% vs 81% | 10-year FFR for large mediastinal adenopathy with E vs without E: 62% vs 58% | nd | nd |

| 10-year OS for small mediastinum with E vs without E: 80 vs 84% | 10-year FFR for small mediastinum with E vs without E: 85% vs 81% | nd | nd | ||||||

| 7 | 1989 | Loeffler et al | 28∗ | E-lesions had no prognostic significance for CR rate, FFTF, OS, or FFP. Six of the patients with stage IIAE disease and 5 of the patients with stage IIBE disease also had MLT. | CMT | 3-year OS: no influence of E-lesions | FFTF: all patients vs E, 20% vs 25%, not significant | nd | CR rate: all patients vs E, 83% vs 81% |

| 1997 | Loeffler et al | 27∗ | Despite E-lesions not routinely irradiated (lung and pleura), there were 100% local CR and no relapses after chemotherapy (median follow-up, 6.5 y). | CMT | nd | nd | No relapses after chemotherapy; median follow-up, 6.5 y | 100% local CR; median follow-up, 6.5 y | |

| 8 | 1989 | Leopold et al | 36∗ | E-lesions had no significant effect on 12-year relapse rate or survival within treatment groups. | RT | 12-year OS: no effect in different treatment groups | nd | Relapse rate not significantly different in treatment groups | nd |

| CMT | 12-year OS: no effect in different treatment groups | nd | Relapse rate not significantly different in treatment groups | nd | |||||

| 10 | 1999 | Shah et al | 37 | E-lesions had no significant influence on relapse rate, OS, or EFS. | RT | 10-year OS: no influence | 10-year EFS: no influence | nd | nd |

| 14 | 2003 | Glimelius et al | 38 | Not significant in 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival | CMT | nd | 10-year DFS and HL-specific survival not significant | nd | nd |

| 22 | 2013 | Song et al | 50 | E-lesion not a significant factor for PFS and OS at 45 months. | All chemo, some CMT | Hazard ratio for OS if E-lesion: 2.581; 95% CI, 0.916-7.273; P = .073 | Hazard ratio for PFS if E-lesion: 1.762; 95% CI, 0.661-4.698; P = .258 | nd | nd |

| C. Studies concluding E-lesions are a poor prognostic factor | |||||||||

| 5 | 1985 | Zittoun et al | 34 | Patients with stage IIE disease had significantly worse 5-year DFS than defined low-risk groups. | CMT | nd | 5-year DFS: significantly worse for patients with stage IIE (significance not provided). | nd | nd |

| 11 | 2000 | Franklin et al | 18∗ | Patients with E-lesions, especially IIBE and IIIE, had a poor prognosis at 5 years. E-lesions were a significant poor prognostic factor beyond IPS. | CMT | nd | DFS: Cox regression with IPS and additional factors after 5 years: stage IIBE and IIIE significant in addition to IPS (P = .017), hazard ratio: 2.62; all E-lesions HR 1.54; P = .086 | nd | nd |