In this issue of Blood Advances, Hedberg et al1 describe the impact of COVID-19 in Sweden in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) comparing the outcomes with those of the general population. Patients with CLL had more severe COVID-19 disease and higher mortality that was worse with therapy. However, these well-known and widely published facts are only part of the story.

The COVID-19 pandemic began in Wuhan, China around December 2019, and it became clear very early in 2020 that this was a novel virus with potentially lethal consequences. The virus quickly spread worldwide. Most developed countries implemented mitigation strategies to “flatten the curve” of infections to protect the community in general and individuals who may be more vulnerable.

Sweden adopted a unique approach among developed nations by not implementing lockdowns and few and nonmandated recommendations for social distancing or the use of masks.1 The result was rapid distribution of the infection with widespread infection levels in the community. This had a dramatic effect on vulnerable populations that resulted in avoidable mortality, particularly in the prevaccination phase, compared with neighboring Nordic and many other countries that did implement public health measures.

Hedberg et al examined 10 national registries in Sweden including a CLL registry to evaluate outcomes of patients with CLL compared with the general community between February 2020 and March 2023 and those born between 1930 and 2003 (ie, aged 17-20 years to 90-93 years during the study period); 6653 had CLL and 8 269 186 did not.

Mortality in the first “wild-type” period was 24.8% in patients with CLL. The 90-day all-cause mortality was 15.0% with CLL and 1.2% without for 2020 to 2023. Just less than half of CLL deaths (84/193; 43.5%) occurred before the 2-dose vaccination was widely deployed in June 2021. This increase in mortality was seen across all age groups in CLL; for example, individuals aged <65 years with and without CLL had mortality rates of 3.6% vs 0.1%. All-cause mortality in patients with CLL in the capital Stockholm rose by 55% in the first 6 months of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.

Hedberg et al also examined outcomes with each of the sequential strains of the circulating virus in COVID-19 (wild-type, Alpha, Delta, and Omicron). The adjusted relative risk of death for patients with CLL vs the population for each COVID-19 strain was 1.95, 2.38, 0.71, and 1.49, respectively. The high mortality with Omicron in CLL in Sweden (after vaccination) is at variance from other countries including neighboring Denmark where Niemann et al2 found a lower mortality rate with Omicron with a 30-day mortality of 2%. However, there were methodological and time-frame differences, and in Denmark, most patients had third and fourth vaccine boosters and preemptive antispike monoclonal antibody.

Importantly, in patients with CLL who had 5 vaccine doses compared with those with lower levels of vaccination, they found no identifiable increase in mortality. This is a key lesson in CLL with the COVID-19 pandemic. Although patients with CLL have significantly impaired immunological responses to vaccination, especially after only the first 2 vaccine doses,3 multiple vaccine doses seroconvert a significantly higher proportion of patients and achieve higher levels of antispike antibody and neutralizing antibody.4 Furthermore, most develop COVID-19–specific T-cell responses, which are likely quite important for protection.4

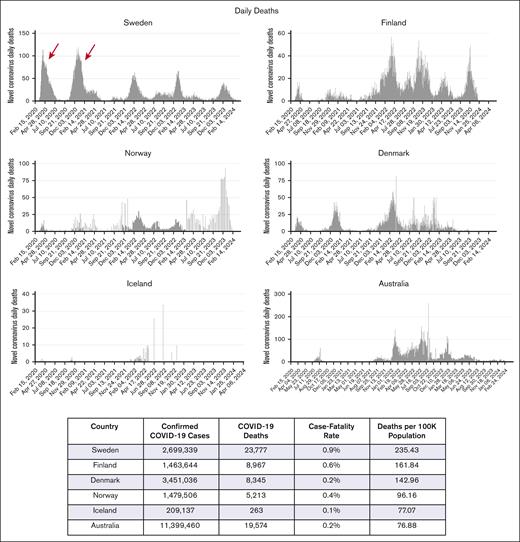

The key period in the COVID-19 pandemic of course is the time before vaccination became available worldwide, mostly during the first half of 2021, when the only protective strategy was avoidance of infection. The impact of public health measures is particularly evident in neighboring Nordic countries where Finland and especially Norway (both sharing land borders with Sweden) and Denmark had markedly lower levels of COVID-19 during 2020 to 2021 (see figure). Island nations such as Iceland and, on the other side of the world, New Zealand also achieved markedly lower levels of COVID-19, albeit with somewhat different approaches, and hence, markedly lower mortality rates.5

Daily deaths (whole population) from COVID-19 in Nordic countries and Australia, from 2020 to 2024. The graphs demonstrate high mortality in Sweden in 2020 to 2021 in the prevaccination phase compared with border-sharing Norway and Finland, with Denmark, Iceland, and Australia. Note the different y-axis with 150 for Sweden; 100 for Denmark, Norway; 60 for Finland; 40 for Iceland; and 300 for Australia. Arrows indicate high mortality rates in the prevaccination phase in Sweden. Graphs from “Worldometer” site (accessed 8 March 2025). Table from Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard site (accessed 4 March 2025).

Daily deaths (whole population) from COVID-19 in Nordic countries and Australia, from 2020 to 2024. The graphs demonstrate high mortality in Sweden in 2020 to 2021 in the prevaccination phase compared with border-sharing Norway and Finland, with Denmark, Iceland, and Australia. Note the different y-axis with 150 for Sweden; 100 for Denmark, Norway; 60 for Finland; 40 for Iceland; and 300 for Australia. Arrows indicate high mortality rates in the prevaccination phase in Sweden. Graphs from “Worldometer” site (accessed 8 March 2025). Table from Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard site (accessed 4 March 2025).

This report by Hedberg et al makes clear the major detrimental effect on patients with CLL. High levels of community infection and transmission made it essentially impossible for patients with CLL and their relatives to protect themselves. Regarding CLL cohorts elsewhere, the authors discuss the reports from our institution in Australia.3,4,6 Australia closed its borders to international travel on 20 March 2020 and also implemented multiple interstate and regional lockdowns aiming for “zero-Covid” until vaccination was available and widely adopted (>96% by late 2021). Although some regions (especially Melbourne) endured prolonged lockdowns, this approach was extremely effective at limiting community infections. It was this effective absence of community COVID-19 infection together with an approach of multiple vaccine doses administered to patients with CLL titrated against measured antispike antibody responses that resulted in a very low mortality rate in our CLL cohort of 241 patients with only a single COVID-19–related death (0.4% overall cohort mortality; a patient with concurrent metastatic melanoma).6

A Swedish commission of inquiry examined the adverse impact and high mortality rate in nursing homes and among the older population. The conclusion was that older individuals could have been better protected7 and the absence of effective mitigation “failed to protect older people.” Worldwide, many older individuals have a monoclonal B-lymphocytosis (MBL) clone; ∼10% to 15% of those older than 60 years.8 These individuals, almost universally unaware of their clone, have impaired immune responses.3 Oliva-Ariza et al9 in Salamanca demonstrated that the incidence of MBL compared with the general population (14%) was more than twice as high in patients with COVID-19 (29%), especially those older than 70 years (49%) and hospitalized cases (40%). This suggests that globally, MBL clones played a significant role in the severity of COVID-19 among individuals older than 65 years. Therefore, focusing solely on patients with CLL represents only the tip of the iceberg for B-cell clone–related COVID-19 infection risk.

The authors conclude “the need for a more pro-active pandemic strategy for CLL” reflecting data in this article that the Swedish approach “failed to protect CLL patients.” Targeted therapies now provide most patients with CLL with excellent disease control and prolonged survival. Therefore, protecting patients with CLL (and older people and other high-risk groups) means protecting the whole community using the public health measures that were not implemented in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.