Key Points

In adolescents with SCD, higher scores on knowledge-related domains were associated with increased confidence in managing their health.

Youth with SCD indicated a preference for starting transition education in their midteens, at least twice a year, using various approaches.

Visual Abstract

Disease and management knowledge is crucial for individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) transitioning from a pediatric to adult health care facility. However, there is a lack of understanding regarding the specific education needed and its association with an individual’s ability to successfully transition. This study aims to explore the association between SCD-specific transition readiness assessment scores, patient characteristics, and the perceived importance and confidence in the individual’s ability to manage their health and transition to an adult doctor. Semistructured interviews provided insights on education gaps and preferences. Eighty-four individuals completed the transition readiness assessment. Younger patients (aged ≤18 years) had significantly lower scores on the appointment (1.1 [standard deviation (SD), 0.7] vs 1.6 [SD, 0.6]; P = .007) and insurance (0.5 [SD, 0.7] vs 1.5 [SD, 1.1]; P = .0006) domains as compared with older (aged >18 years) individuals. Those who were very confident in their ability to manage their health care had significantly higher scores in disease knowledge (2.4 [SD, 0.5] vs 2.0 [SD, 0.7]; P = .01), medication management (2.5 [SD, 0.6] vs 2.1 [SD, 0.4]; P = .0001), appointments (1.4 [SD, 0.7] vs 0.9 [SD, 0.5]; P = .0006), and insurance (0.9 [SD, 0.9] vs 0.5 [SD, 0.8]; P = .02), compared with those who were not. Semistructured interviews with 9 young adults revealed a preference for transition education to start in their midteens, at least twice a year, and using a combination of approaches. Additional themes identified included the desire for ongoing education, familiarity with the workflow and environment, access to care, and the importance of support systems during their transition.

Introduction

Individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) need regular clinical care throughout their life span to prevent complications due to their underlying condition. Transitioning from pediatric to adult health care facilities is a particularly challenging process for individuals with SCD. The adolescents and young adults undergo numerous changes, not only in terms of their health care system, but also at the physical, psychological, and social levels. Some barriers specific to SCD transition include physician mistrust, access to care, insurance, employment, and stress in personal relationships.1 In addition, studies report a lack of transition readiness among children with SCD.2-5 Data also support that health outcomes are worse during the transition period, during which acute care utilization,6 emergency department reliance,7 and prevalence of end-organ complications8 are significantly higher among individuals in transition ages as compared with the pediatric age group. These issues highlight the need for education as individuals with SCD transition from pediatric to adult health care systems, and an opportunity for improvement of care.

Transition programs for SCD are increasingly included in comprehensive pediatric SCD. However, the specific elements and tools used vary across SCD transition programs. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) has developed an SCD transition readiness assessment tool to evaluate how prepared young adults with SCD are to transition to adult health care; however, there are no published studies using the SCD transition readiness assessment tool. The strengths of this tool are that it includes SCD-specific domains along with an overall assessment of the child’s perceived ability and confidence regarding transitioning to adult health care.

Current transition programs are often informed by pediatric studies, and do not capture the experiences of people who have already transitioned to the adult health care system. Transition is a process that extends beyond pediatric care. Hence, young adults who have recently transitioned may be able to identify specific needs and important aspects of care that they may have liked to know before transitioning to adult health care. To better understand the transition readiness among youth with SCD in terms of knowledge, and learn the perspectives of young adults about transition education, we conducted a sequential explanatory mixed methods study including a quantitative and qualitative component.

The objectives of the quantitative study are to determine transition readiness, describe knowledge on specific health management domains using the ASH transition readiness tool, and examine differences in scores by patient characteristics. Our primary hypothesis was that older individuals and those with less social vulnerability would exhibit higher transition readiness. Our secondary hypothesis was that knowledge about disease, medications, appointments, and insurance would be associated with greater confidence in the ability to transition.

The qualitative phase of the study aims to better understand the perspectives of young adults to gather insights on how transition education could be tailored to meet their needs, and facilitate transition from pediatric to adult health care. These findings will inform clinical programs about the design and structure of interventions to facilitate transition of young adults with SCD.

Methods

Sequential mixed methods design

We used a sequential explanatory mixed methods design. The quantitative phase aimed to describe patient characteristics, assess transition readiness using the ASH transition readiness assessment tool, and explore differences in scores by age, sex, social vulnerability, and SCD genotype.

The sequential explanatory design was chosen because it allows for a comprehensive analysis where quantitative findings are clarified through qualitative exploration.9,10 In this study, the quantitative data provided a broad assessment of transition readiness, whereas the qualitative phase, through semistructured interviews, offered insight into personal experiences and increased our understanding of knowledge gaps.11,12 This approach was ideal for understanding not only the measurable outcomes and knowledge gaps, but also the deeper contextual factors13 that impact successful transitions, such as social support and the role of health care providers.

Quantitative phase

We identified individuals with SCD between the ages of 15 and 22 years (as of 31 December 2022) receiving care at a large comprehensive SCD clinic, and determined their characteristics by leveraging data in the statewide Sickle Cell Data Collection Program in Wisconsin. The patient's characteristics included age, sex, race, social vulnerability index, SCD genotype, and the frequency of visits to the pediatric SCD specialty clinic in a year. For individuals with transition assessments, we determined the number of visits 1 year before the completion of the assessment. For individuals with no assessment, pediatric visits were determined as follows: for those aged ≤19 years, the number of visits during 2022 was counted; and for those aged >19 years, visits were counted during the time when they were between 18 and 19 years of age. These data were linked with transition readiness information collected in the SCD clinic for children with SCD. The transition readiness assessments were incorporated into the pediatric SCD clinic in 2020. The SCD clinic programmatically assesses transition readiness among individuals aged ≥15 years, using the transition readiness assessment tool developed by ASH. The clinical team chose to use the tool in clinical practice as a point of care tool to identify areas that could be addressed in the context of current and future clinic visits to determine areas of need for individual patients. Furthermore, this tool is specific to SCD, developed and endorsed by ASH, and is formatted on 1 page, making it easier to administer in a paper format. Surveys were administered twice a year when possible. Disease-specific education was delivered by related disciplines (physician, nurse, psychologist, genetic counselor, and social worker). A formal transition program was not in place at the time of data collection, and a transition navigator was not part of the SCD program. Meetings with the local adult SCD team were held quarterly to discuss individuals transitioning to adult care. This study analyzes the transition readiness scores from the first time the adolescents completed the assessment. The tool provides an assessment and summary form designed to facilitate conversations between providers, patients, and their families as the patient transitions from pediatric to adult care, and includes 3 overarching questions. These questions are scaled from 0 to 10 to assess the importance of self-care and confidence about the individual’s ability to manage their health care and changing to an adult doctor. Responses ranging between 0 and 3 were categorized as the individual rating self-care importance and confidence as “minimal,” between 4 and 7 as “moderate,” and between 8 and 10 as “very.”

In addition, there are 5 domains assessing knowledge specific to disease, medication management, appointments, insurance, and privacy information. Questions in these domains are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “No, I do not know” to “Yes, I always do this when I need to.” There is no published or accepted standard method of scoring the ASH transition readiness assessment tool kit; hence, we adapted the methodology described by previous studies for other surveys such as the RAND 36–item health survey14,15 to convert the Likert scale responses to numerical scores. We calculated scores for each of the 5 domains based on the following steps: (1) the Likert scale responses were transformed linearly to a numerical score ranging from 0 to 3, (2) scores based on responses to the questions were summed within a particular domain, and (3) summed scores were divided by the number of questions answered within that domain. A score of 0 indicates no knowledge about any of the questions listed in the domain, whereas a score of 3 indicates that the patient had complete knowledge and leveraged it as needed.

We compared demographic (sex, high social vulnerability index) and clinical characteristics (genotype of SCD) between individuals with SCD receiving care at the specialty clinic who completed the transition readiness assessment and those who did not, using χ2 test. The number of visits to the pediatric SCD specialty clinic in a year were compared using negative binomial models. The state-specific social vulnerability index ranks each county relative to other counties within the state on 16 social factors. Percentile ranking values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater vulnerability. For those who completed the assessment, we described the transition readiness, and determined if there were differences in scores by patient characteristics using the Mann-Whitney U test. Social vulnerability index characteristics were quantified using the 2020 state-specific databases based on county of residence. We used the Mann-Whitney U test to examine whether the domain scores related to knowledge about disease, medication management, appointments, insurance, and privacy information were associated with perceived importance and confidence related to managing their own health and transitioning to an adult doctor.

Qualitative phase

We recruited a convenience sample of 9 young adults (19-25 years) from an adult specialty SCD clinic. This is the only SCD specialty clinic in the county that treats adults with SCD. All patients who receive care at the local pediatric SCD program are referred to this adult clinic once they turn 19 years.

The research team approached eligible patients (19-25 years of age, no cognitive impairment, English speaking, and any genotype) at the adult SCD clinic following their medical appointment to request for their consent to participate in a semistructured interview. The interviews were conducted virtually. The interviews were recorded, deidentified, and transcribed for thematic analysis.

The framework approach16 was used to guide the qualitative data analysis, aligning with the study’s objective to identify key factors influencing transition readiness and education among young adults with SCD. This approach is particularly well suited for studies with predefined objectives, like ours, as it provides a systematic and flexible structure for organizing and interpreting complex qualitative data. By enabling both deductive and inductive analyses, this method allowed us to systematically explore participants’ experiences while remaining open to uncovering emergent themes that were not initially anticipated. The analysis followed 5 stages: (1) familiarization, coders immersed themselves in the data through the transcript and audio review; (2) identifying a thematic framework, informed by preliminary insights from the quantitative phase; (3) indexing, key codes were applied to segments of the data; (4) charting, involved organizing data into a matrix based on identified themes; and (5) mapping and interpretation, relationships between themes were explored and findings synthesized.

The first 2 young adults’ transcripts were coded independently by 3 members of the team, who convened to discuss and consolidate the initial codes, subthemes, and themes. These were refined through multiple iterations. Of the 9 transcripts, 4 were coded independently by at least 2 members of the team, and additional revisions were made to the list of codes as needed based on every subsequent coded interview. The study members met regularly to discuss findings and resolve any discrepancies in coding, following recommended methods.12

To ensure the fidelity of our findings, we followed Guba and Lincoln criteria,17 focusing on credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Techniques such as constant comparison were used to refine the thematic framework as new data were analyzed, and deviant case analysis was used to ensure contradictory or outlier data were considered.18

The quantitative part of the study is a part of the Sickle Cell Data Collection Program, which is a surveillance program approved under the Common Health Rule. The qualitative part of the study is approved by the institutional review board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Results

Quantitative phase

There were 205 individuals with SCD, aged 15 to 22 years, who received care at a tertiary health care facility during 2013 to 2022. Since then, 84 individuals (41%) completed the assessments. The mean age at the time of transition assessment completion was 16.5 years (standard deviation [SD], 1.3), and 97.6% of them were Black and non-Hispanic or Latino. A significantly higher proportion of those with assessments had hemoglobin SS/Sβ0 thalassemia disease as compared with those who did not have the assessments done. Those who completed transition assessments also had a higher number of pediatric SCD visits in the year prior to assessment completion compared with those who did not complete these assessments. There were no other significant differences between those that had completed the transition readiness assessment and those who had not (Table 1).

Characteristics of individuals aged 15 to 22 years with SCD who completed the ASH SCD transition readiness assessment tool and those who did not

| . | 15-22 years (N = 205), n (%) . | With assessment (n = 84), n (%) . | No assessment (n = 121), n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 109 (53) | 46 (55) | 63 (52) | .70 |

| SVI∗ | ||||

| Not very high (1) ≤0.75 | 26 (14) | 10 (12.2) | 16 (15.4) | .53 |

| Very high (2) >0.75 | 160 (86) | 72 (87.8) | 88 (84.6) | |

| SCD type† | ||||

| Hemoglobin SS/Sβ0 thalassemia (1) | 94 (54.7) | 49 (63.6) | 45 (47.4) | .03 |

| Others (0) | 78 (45.3) | 28 (36.4) | 50 (52.6) | |

| Visits to pediatric SCD specialty clinic, median (interquartile range) | 0 (0-3) | 3 (1-4) | 0 (0-0) | <.0001 |

| . | 15-22 years (N = 205), n (%) . | With assessment (n = 84), n (%) . | No assessment (n = 121), n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 109 (53) | 46 (55) | 63 (52) | .70 |

| SVI∗ | ||||

| Not very high (1) ≤0.75 | 26 (14) | 10 (12.2) | 16 (15.4) | .53 |

| Very high (2) >0.75 | 160 (86) | 72 (87.8) | 88 (84.6) | |

| SCD type† | ||||

| Hemoglobin SS/Sβ0 thalassemia (1) | 94 (54.7) | 49 (63.6) | 45 (47.4) | .03 |

| Others (0) | 78 (45.3) | 28 (36.4) | 50 (52.6) | |

| Visits to pediatric SCD specialty clinic, median (interquartile range) | 0 (0-3) | 3 (1-4) | 0 (0-0) | <.0001 |

Bold indicates statistically signficant P values < .05.

SVI, social vulnerability index.

SVI missing for 19 individuals.

SCD diagnosis missing for 33 individuals.

Of the 84 who had an assessment, 23 were >19 years of age as of 31 December 2022. Of these, 12 (52%) had at least 1 completed visit with the adult SCD clinic by the end of 2022. There was 1 individual who was 18.7 years of age who had a completed visit with the adult SCD clinic.

Of the 121 individuals who did not have an assessment, 29 were >19 years of age, and 5 (17%) had at least 1 completed visit with the adult SCD clinic by the end of 2022.

Transition readiness assessment

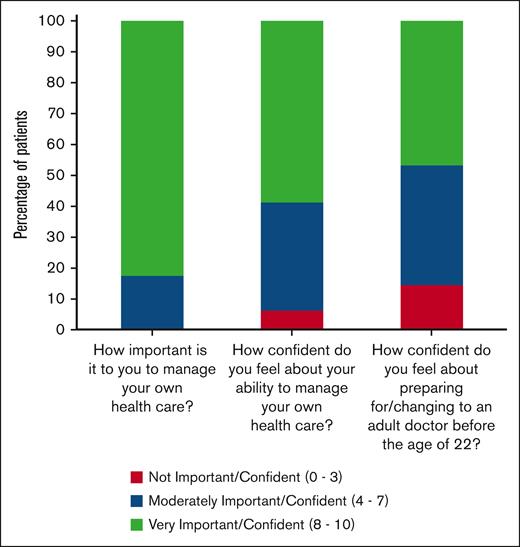

Most individuals (n = 66 [82.5%]) reported that it was very important for them to manage their own health care. However, only 47 individuals (58.7%) felt very confident about their ability to do so, and only 35 (44%) felt very confident about preparing for/changing to an adult doctor before 22 years of age (Figure 1). Table 2 displays the mean transition readiness assessment scores (SD) for our sample (box plots provided in supplemental Figure 1).

Distribution of responses related to self-care importance and confidence among those who were administered the transition readiness assessment. The 3 questions related to patients’ perceived importance to manage their health and their confidence in the ability to so, and transition to an adult doctor are represented on the x-axis. The y-axis indicates the percentage of patients. Each section within the bar graph represents the percentage of patients with a response within the specified categories.

Distribution of responses related to self-care importance and confidence among those who were administered the transition readiness assessment. The 3 questions related to patients’ perceived importance to manage their health and their confidence in the ability to so, and transition to an adult doctor are represented on the x-axis. The y-axis indicates the percentage of patients. Each section within the bar graph represents the percentage of patients with a response within the specified categories.

Domain scores by individuals’ perceived importance and confidence in managing their own health care

| Domain . | Overall mean (SD) score . | How important is it to you to manage your own health care?∗ . | How confident do you feel about your ability to manage your own health care?∗ . | How confident do you feel about preparing for/changing to an adult doctor before the age of 22?∗ . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | ||

| Disease knowledge† | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.6) | .18 | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.5) | .01 | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.5) | .08 |

| Medication management† | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | .68 | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.6) | .0001 | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.5) | .10 |

| Appointments‡ | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.7) | .13 | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.7) | .0006 | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.7) | .008 |

| Insurance§ | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.8) | .60 | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.9) | .02 | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.9) | .03 |

| Privacy§ | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | .56 | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.2) | .77 | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | .46 |

| Domain . | Overall mean (SD) score . | How important is it to you to manage your own health care?∗ . | How confident do you feel about your ability to manage your own health care?∗ . | How confident do you feel about preparing for/changing to an adult doctor before the age of 22?∗ . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | Minimal/moderate . | Very . | P value . | ||

| Disease knowledge† | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.6) | .18 | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.5) | .01 | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.5) | .08 |

| Medication management† | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | .68 | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.6) | .0001 | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.5) | .10 |

| Appointments‡ | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.7) | .13 | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.7) | .0006 | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.7) | .008 |

| Insurance§ | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.8) | .60 | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.9) | .02 | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.9) | .03 |

| Privacy§ | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | .56 | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.2) | .77 | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | .46 |

Bold indicates statistically signficant P values < .05.

One individual with missing response to the domain.

Response to 1 question missing for 2 individuals.

Response to 1 question missing for 3 individuals.

Four individuals with missing response.

Association between sociodemographic factors and knowledge-related domains

Younger patients (aged ≤18 years) had significantly lower scores on the appointment (1.1 [SD, 0.7] vs 1.6 [SD, 0.6]; P = .007) and insurance (0.5 [SD, 0.7] vs 1.5 [SD, 1.1]; P = .0006) domains as compared with older individuals (aged >18 years); however, scores were overall low within the specific age groups. There were no significant differences for any other domains by age, sex, social vulnerability index, and type of SCD.

Association between knowledge-related domains and perceived importance/confidence about disease self-management and changing to an adult doctor before the age of 22 years (Table 2).

There were no differences in any of the domain scores between individuals who considered it very important to manage their health care compared with those who did not. However, those who expressed being very confident in the ability to manage their health care had significantly higher scores for disease knowledge (2.4 [SD, 0.5] vs 2.0 [SD, 0.7]; P = .01), medication management (2.5 [SD, 0.6] vs 2.1 [SD, 0.4]; P = .0001), appointments (1.4 [SD, 0.7] vs 0.9 [SD, 0.5]; P = .0006), and insurance (0.9 [SD, 0.9] vs 0.5 [SD, 0.8]; P = .02) than those who were only moderately confident or not confident. In addition, individuals who felt very confident about preparing for or changing to an adult doctor had higher knowledge regarding appointment making (1.4 [SD, 0.7] vs 1.0 [SD, 0.6]; P = .008) and their insurance (0.9 [SD, 0.9] vs 0.5 [SD, 0.9]; P = .03).

Qualitative phase

Nine individuals with SCD who transitioned to the adult health care system participated in the qualitative phase of the study (demographic and clinical characteristics of these participants provided in supplemental Table 1). The mean and median time between the first visit to the adult SCD specialty clinic and the conduct of the semistructured interviews for our sample was 37.5 and 34.8 months, respectively, ranging from 5.1 to 56.5 months. The themes identified in the interviews were grouped into 2 domains: (1) transition education and needs and (2) educational approaches. The transition education and needs domain encompassed 5 key themes (Table 3). The second domain, educational approaches, highlights themes related to preferred methods and cadence of content (Table 3). Hereafter, the identified themes for these 2 domains are described.

The inductive themes and subthemes from the semistructured interviews for the 2 domains: transition education and need, and educational approaches

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Quotes . |

|---|---|---|

| Transition education and need domain | ||

| Endorsed age for transition | Preferred age range | “I’d say midteens because I feel like late teens might be too late. By then, the person would already be in the middle of the transition and still trying to learn.” (R8) |

| Avoiding urgency to learn | “I really didn't have no help like for as actually getting on that side like I just felt like it was rushed and everything was just like so fast.” (R2) | |

| Knowledge about SCD | Existing knowledge | “So things like elevating my legs, putting them on pillows or rolled up blankets, heating pads, and staying on top of like ibuprofen or Tylenol and stuff so like little, little remedies at home to try and get me through until the pain passes and if that doesn't work then I know that I'll need to go in.” (R9) |

| Knowledge gap | “I didn’t know anything about the labs honestly until I really made the transition. Now and like I know what certain abbreviations are or where my blood levels are supposed to be at, but I didn’t know that in pediatrics.” (R1) | |

| Patient engagement | “It’s mostly because I ask a lot of questions—I’m a big question asker. I like to get consistent answers, but it depends on what infusions I’m on or what’s happening with my treatment, and how to approach it. But, you know, different things work for different people.” (R2) | |

| Support system | Family and peer support | “I didn’t feel so helpless. I had an idea of what to expect here and there. I had a good support system—my mom would usually ask questions, and my dad too. So, I never really felt like I was on my own.” (R10) |

| Health care provider support | “I think like once a year or every other year they would, you know, brought some paperwork and always and went over, you know, how my sickle cell works. And show me, you know, like models or pictures and all that. Just basically everything to fully explain how, you know…What’s going on inside my body, how they are treating it, the medicines they are now prescribing me.” (R4) | |

| Familiarity with health care system | Setting expectations | “I feel like we should have been taught more like, you know, everything is not going to be the same where everything is not gonna be how it was over here when you get over here like I feel like they should also tell you how it’s going to be or show you or give you some ideas or how it’s gonna be when you get over there because it’s not the same not even a little bit like nothing about it is the same so I feel like you should be prepared before just going over there.” (R1) |

| Environment and workflow | “I still have appointments now I have to make, but I don’t know how to get around the hospital, so I don’t fully make them yet, because I don't know how to get around.” (R5) | |

| Access to care | Insurance | “There is one that I’m not on right now due to my insurance because my dad he’s not reliable with insurance, so it’s a complication between me and my insurance but they have recommended it.” (R5) |

| Transportation | “I need help getting to appointments, because every appointment I usually come to, if my mom or dad doesn’t bring me, I call Uber. And so…either I didn’t have money on my card or I forgot cause sometimes.” (R11) | |

| Use of technology | “Cause I check my chart often (to learn about treatment). And only to keep up to date with it every time I have an appointment.” (R6) | |

| Educational approaches domain | ||

| Modes of education | Combination of approaches | “I was talking to my doctors at the time, as well as the nurses. The provider also helped me understand some of the medications I’m on. I also like to Google my medications, so I know exactly what I’m taking.” (R10) |

| Visual learning aids | “Yeah, basically just the packets, the ones that give a quick overview. The visuals make it easier for me to understand how things really work. When I read, I can imagine it, but actually seeing it helps me really register the whole process and what’s going on.” (R4) | |

| Printed text | “I really prefer reading things on paper.” (R1) | |

| Class setting | “I don’t have any issues with that (group/class setting). I actually think it would be a good idea, especially for people who feel alone in trying to get information or who don’t have a strong support system.” (R10) | |

| Awareness through social media | “You can join groups on there, post statuses or updates, and people will comment. It’s a way to connect with others who have sickle cell, and it also allows us to compare treatments and share experiences.” (R9) | |

| “I’m scared of online, because you know, sometimes they don't know what they’re talking about. And so I feel like the best person to ask is my doctor, or like nurses.” (R11) | ||

| Peer education | “Yes, I do talk to the providers. They usually ask me every time I go in, and I always tell them, ‘all of the above’—whatever information they can give me, in any way they can, it helps.” (R8) | |

| Cadence of content | Frequency of education | “Every 2 weeks, you know, something like that. I feel like it should be more like you should have at least have probably you could do up to 3 days a month. You could do once a week. You can do every 2 weeks.” (R2) |

| Incorporating quiz to the education program | “Being pushed the information on and on and on again and you already know it can get irritating because you already know, but I feel like it should be like a type of quiz or a test to see where you’re at so you know.” (R5) | |

| Opportunity during care visit | “It depends on people’s appointments and whenever you’re seen at the hospital as you have to be there for a couple of hours. I say that’s the perfect time to get any information. Also, with being admitted too, I feel like it should be pushed every admission that’s longer than 3 to 4 days because it’s like, hey, since you're here.” (R5) | |

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Quotes . |

|---|---|---|

| Transition education and need domain | ||

| Endorsed age for transition | Preferred age range | “I’d say midteens because I feel like late teens might be too late. By then, the person would already be in the middle of the transition and still trying to learn.” (R8) |

| Avoiding urgency to learn | “I really didn't have no help like for as actually getting on that side like I just felt like it was rushed and everything was just like so fast.” (R2) | |

| Knowledge about SCD | Existing knowledge | “So things like elevating my legs, putting them on pillows or rolled up blankets, heating pads, and staying on top of like ibuprofen or Tylenol and stuff so like little, little remedies at home to try and get me through until the pain passes and if that doesn't work then I know that I'll need to go in.” (R9) |

| Knowledge gap | “I didn’t know anything about the labs honestly until I really made the transition. Now and like I know what certain abbreviations are or where my blood levels are supposed to be at, but I didn’t know that in pediatrics.” (R1) | |

| Patient engagement | “It’s mostly because I ask a lot of questions—I’m a big question asker. I like to get consistent answers, but it depends on what infusions I’m on or what’s happening with my treatment, and how to approach it. But, you know, different things work for different people.” (R2) | |

| Support system | Family and peer support | “I didn’t feel so helpless. I had an idea of what to expect here and there. I had a good support system—my mom would usually ask questions, and my dad too. So, I never really felt like I was on my own.” (R10) |

| Health care provider support | “I think like once a year or every other year they would, you know, brought some paperwork and always and went over, you know, how my sickle cell works. And show me, you know, like models or pictures and all that. Just basically everything to fully explain how, you know…What’s going on inside my body, how they are treating it, the medicines they are now prescribing me.” (R4) | |

| Familiarity with health care system | Setting expectations | “I feel like we should have been taught more like, you know, everything is not going to be the same where everything is not gonna be how it was over here when you get over here like I feel like they should also tell you how it’s going to be or show you or give you some ideas or how it’s gonna be when you get over there because it’s not the same not even a little bit like nothing about it is the same so I feel like you should be prepared before just going over there.” (R1) |

| Environment and workflow | “I still have appointments now I have to make, but I don’t know how to get around the hospital, so I don’t fully make them yet, because I don't know how to get around.” (R5) | |

| Access to care | Insurance | “There is one that I’m not on right now due to my insurance because my dad he’s not reliable with insurance, so it’s a complication between me and my insurance but they have recommended it.” (R5) |

| Transportation | “I need help getting to appointments, because every appointment I usually come to, if my mom or dad doesn’t bring me, I call Uber. And so…either I didn’t have money on my card or I forgot cause sometimes.” (R11) | |

| Use of technology | “Cause I check my chart often (to learn about treatment). And only to keep up to date with it every time I have an appointment.” (R6) | |

| Educational approaches domain | ||

| Modes of education | Combination of approaches | “I was talking to my doctors at the time, as well as the nurses. The provider also helped me understand some of the medications I’m on. I also like to Google my medications, so I know exactly what I’m taking.” (R10) |

| Visual learning aids | “Yeah, basically just the packets, the ones that give a quick overview. The visuals make it easier for me to understand how things really work. When I read, I can imagine it, but actually seeing it helps me really register the whole process and what’s going on.” (R4) | |

| Printed text | “I really prefer reading things on paper.” (R1) | |

| Class setting | “I don’t have any issues with that (group/class setting). I actually think it would be a good idea, especially for people who feel alone in trying to get information or who don’t have a strong support system.” (R10) | |

| Awareness through social media | “You can join groups on there, post statuses or updates, and people will comment. It’s a way to connect with others who have sickle cell, and it also allows us to compare treatments and share experiences.” (R9) | |

| “I’m scared of online, because you know, sometimes they don't know what they’re talking about. And so I feel like the best person to ask is my doctor, or like nurses.” (R11) | ||

| Peer education | “Yes, I do talk to the providers. They usually ask me every time I go in, and I always tell them, ‘all of the above’—whatever information they can give me, in any way they can, it helps.” (R8) | |

| Cadence of content | Frequency of education | “Every 2 weeks, you know, something like that. I feel like it should be more like you should have at least have probably you could do up to 3 days a month. You could do once a week. You can do every 2 weeks.” (R2) |

| Incorporating quiz to the education program | “Being pushed the information on and on and on again and you already know it can get irritating because you already know, but I feel like it should be like a type of quiz or a test to see where you’re at so you know.” (R5) | |

| Opportunity during care visit | “It depends on people’s appointments and whenever you’re seen at the hospital as you have to be there for a couple of hours. I say that’s the perfect time to get any information. Also, with being admitted too, I feel like it should be pushed every admission that’s longer than 3 to 4 days because it’s like, hey, since you're here.” (R5) | |

R, respondent.

Transition education and needs domain

Endorsed age for transition education

Most participants indicated that midteen years (15-17 years) were the ideal time to begin transition education. However, a smaller subset of participants favored starting even earlier, in the early teens, to prevent a rushed or urgent transition process.

Knowledge about SCD

Most participants were familiar with their SCD type, medications, and how to manage a pain crisis. However, they wanted to learn more about interpreting laboratory results, the connection between SCD and other comorbidities, and ongoing medication education. Participants reported that much of their existing knowledge came from clinics, peer groups, and personal research, often prompted by asking providers questions or searching online.

Support system

The support offered by peers and family members before, during, and after transition was recognized by numerous participants. Some received support from peer groups through social media apps specific for individuals with SCD. Informative SCD providers and consistent communication from the clinical team also aided transition.

Familiarity with the health care system

Participants emphasized the importance of setting expectations and learning about the adult health care system before transitioning. They commonly expressed the need to become familiar with adult health care providers, facilities, and workflows before making the transition.

Access to care

Difficulties accessing recommended care due to insurance challenges during the transition period were mentioned during the interview. Some stated transportation as a barrier to getting to medical appointments. Most noted they relied on patient chart apps to stay informed about laboratory results, treatments, and medical appointments as they navigated the adult health care system.

Educational approaches domain

Mode of education

Most endorsed the need for a combination of approaches, including printed text and visual representation. Visual aids resonated with participants and appeared to have a long-lasting impact. Participants recommended class setting and education from peers in groups as effective modes of education. Education through social media had mixed responses, although some participants were excited about social media as a means of sharing experiences. Others expressed concern regarding the possibility of inaccurate knowledge disseminated via such platforms.

Cadence of content

The recommended frequency of education varied from every 2 weeks to 2 to 3 times per year. There were recommendations to leverage the opportunity during outpatient and inpatient visits to educate the eligible patients about health care transition. There was also a recommendation to include a quiz to identify areas of need for a targeted education plan. Participants had mixed opinions regarding education via social media.

Discussion

Disease-specific education can play a vital role in patients’ ability to successfully establish care after transition. Our study shows that a large proportion of adolescents placed high importance on self-management of their health care; however, <60% felt confident about their ability to do this. Those who did feel confident about their ability to manage their health care had significantly higher knowledge regarding their disease, medication management, appointment making, and insurance. In addition, qualitative analyses provided insight into the areas of need for transition education, the optimal age, mode, and its cadence.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that describes transition readiness using ASH’s transition tool kit specifically developed for individuals with SCD. Numerous transition readiness assessment tools have been used to understand transition readiness among pediatric and young adults with SCD; however, they are often not specific to SCD.2,3 An SCD-specific transition readiness assessment tool exists, the Transition Intervention Program-Readiness For Transition.19 Future studies comparing the performance measures of these tools are needed.

Our mixed method offers a unique perspective that has not been widely captured in existing research, and furthers the understanding of the quantitative results of the study. There are only a few qualitative studies that include young adults,20,21 however, those aim to identify facilitators and barriers of transition, and are not focused on transition education. The qualitative part of our study includes the perspectives of young adults recruited from an adult SCD clinic, offering insights about transition education and shedding light on what specific education could have facilitated their transition.

The high level of disease-related knowledge and medication management among adolescents who completed transition assessment surveys was echoed in the qualitative interviews among an independent sample of young adults who felt they had basic knowledge about their disease and medications. The interviews revealed that individuals wanted to learn more about interpreting laboratory results, SCD-associated comorbidities, and needed ongoing education about medications. Our study identifies opportunities to enhance transition education, and supports the concept that disease and medication education is not only needed during health care transition but should extend across the individuals’ life span. These additional opportunities related to transition education could significantly improve the transition outcomes for all individuals with SCD. Future work is needed to determine the association between transition readiness assessment scores and transition outcomes, such as successfully completing a visit with adult SCD specialty clinics after transfer from pediatric care.

Individuals with SCD often establish care with pediatric providers very early in life; thus, the pediatric health care system has a unique opportunity to prepare and educate individuals with SCD about the upcoming changes as they become adults. Our findings indicate that setting expectations about how the adult health care system operates and helping patients become familiar with the new environment before transition may result in a more seamless and successful transition process. This requires an organizational culture change in which pediatric and adult models partner together to help the transition process. A similar inductive theme related to differences in pediatric and adult care models and the need to build relationships between patients and adult SCD providers was reported in a recently published study that included young adults with SCD.21

In addition, becauseindividuals with SCD recognized the importance of a support system made up of their family, peers, and informed health care providers, engaging families during the transition process may further help individuals with SCD understand the importance of establishing care with adult SCD providers. This is complementary to the understanding of privacy law changes as individuals turn 18 years old. Overall, there was low understanding of how health care privacy changes when an individual is legally an adult. If families are aware of the legal changes around health care privacy, they may be more informed about the importance of helping their child gain independence as they transition. This may involve learning more about the transportation services available to get to their appointments, and addressing other social determinants of health that can be a barrier to accessing care. In addition, introducing digital tools to access their medical records as they transition to adult health care providers could help patients access their medical history and be up to date with their appointments.

Finally, numerous interventions have been shown to be effective to impart disease education.22-24 However, these typically do not include patients’ inputs in design and implementation. Our findings from the qualitative interview endorse the need for transition education imparted via a combination of approaches, at least 2 to 3 times a year, and are consistent with the framework that centers the patients in the development of clinical and related educational programs.

Our study has a few limitations. First, the quantitative part of the study leveraged transition readiness assessment data collected as part of the SCD clinical program. Therefore, we could not include detailed information on education or family income that may be associated with transition readiness and access to available resources. Our study is very homogenous in terms of race and ethnicity; however, this is reflective of the SCD population in the state. Additional multisite studies including individuals with varied race and ethnicity could add further insight related to transition readiness and education of those with distinct cultural backgrounds. Participants for the qualitative interviews were recruited from the adult SCD specialty clinic. Therefore, our findings may be biased toward individuals with SCD who successfully transitioned to adult health care. Future research, partnering with community-based organizations, is needed to understand the barriers faced by individuals with SCD who have not been able to make this transition. Also, because the participant group for the qualitative interviews is highly specific, recruitment challenges limited our sample to 9 participants. However, the focused nature of this study allowed for an in-depth exploration of key themes, and provided valuable insight related to transition readiness in individuals with SCD. Finally, these findings may have limited generalizability. However, the consistency in qualitative themes across interviews and given we included the assessments done as part of the clinical practice and not as a research data collection project make these findings informative, and add valuable information to the SCD transition literature.

Conclusions

Patients’ confidence in their ability to manage their own health and establish care with adult providers is associated with their knowledge about appointment making/keeping and insurance plans. Other domains related to patients’ confidence about their ability to manage health care include disease knowledge and medication management. Those recently transitioned to the adult health care system expressed continued need for education and familiarity with the adult health care system before transitioning. Future work is needed to determine if concerted efforts to prepare pediatric patients improves their health outcomes as they establish care with the adult health care system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Collaborative Healthcare Delivery Science Fellowship (Medical College of Wisconsin) and the Sickle Cell Data Collection Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A.M.B. reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R01HL142657) and NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (4R33NS114954).

Authorship

Contribution: A.S. designed and performed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; M.D. analyzed data and critically edited the manuscript; M.M.N. performed research, designed surveys, analyzed qualitative data, and critically edited the manuscript; N.S. performed research, analyzed qualitative data, and critically edited the manuscript; J.K. interpreted data, collected data, and critically edited the manuscript; M.M. interpreted quantitative data, collected data, and critically edited the manuscript; J.J.F. interpreted data and critically edited the manuscript; M.A. analyzed qualitative data, interpreted data, and critically edited the manuscript; L.E.P. designed research, interpreted data, and critically edited the manuscript; and A.M.B. designed research, interpreted data, and critically edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.J.F. reports research studies in sickle cell disease with Vifor, Shire, and Forma (unrelated to submitted manuscript). A.M.B. is on an adjudication committee for a clinical trial sponsored by Pfizer (unrelated to the submitted research). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ashima Singh, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 W Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; email: ashimasingh@mcw.edu.

References

Author notes

Data sharing is permissible only in accordance with data use agreements and subject to approval by the institutional review board. For questions, please contact the corresponding author, Ashima Singh (ashimasingh@mcw.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.