TO THE EDITOR:

The term “classical hematology” (CH), referring to a subspecialty focusing on noncancer blood disorders, was officially adopted by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in 2022.1 There is a perceived shortage in classical hematologists. In a 2017 survey conducted by the ASH, 46% of 2500 practicing hematologists reported a shortage of classical hematologists. This led to the subsequent discovery that <5% of hematology-oncology fellows were interested in pursuing a career in CH.2 Unfortunately, career interest in CH has not increased in the last 2 decades.3,4 Although actual supply/demand in the CH workforce has not been quantified, focus groups conducted by the ASH identified grave concerns due to a perceived shortage of trainees and physicians specializing in CH compared with the immense clinical demand.5 Moreover, mentorship was consistently cited as the most important factor guiding trainees’ career decisions.4,5 To help fill this CH workforce gap, the ASH has recently established, and is funding, the Hematology-Focused Fellowship Training Programs (HFFTPs) across 9 institutions. Subsequently, 3 additional, self-funding hematology-oncology fellowship programs have joined the ASH HFFTP, forming a final consortium of 12, all at institutions with National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers.6

There are currently no published data on the number of classical hematologists in the United States. The goals of our study were to (1) determine the number of adult hematologist-oncologists within NCI-designated cancer centers who practice CH and (2) compare the characteristics of physicians within these cancer centers with and without an HFFTP.

We included all adult NCI-designated cancer centers with a clinical program as of 1 April 2024. We obtained the practice profile of internal medicine–trained adult hematologist-oncologists (henceforth, physicians) as well as the presence of HFFTPs from the respective institutional websites. We also searched the corresponding department of medicine and division of hematology websites at each affiliated academic institution to ensure the inclusion of all physicians practicing CH. Each physician was classified into 3 categories: (1) classical hematologist (attending to only noncancer conditions), (2) general hematologist-oncologist (attending to cancer and noncancer conditions), and (3) oncologist (attending to cancer only).

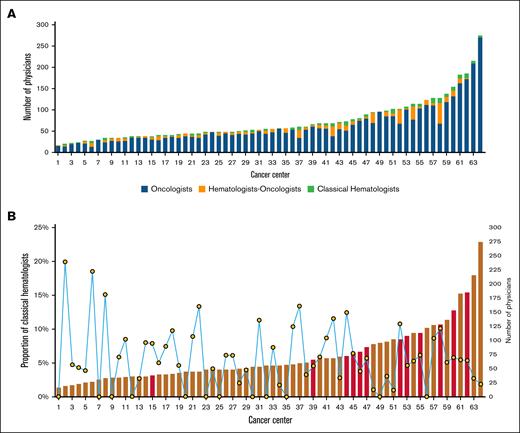

We included 64 NCI-designated cancer centers, 55 (85.9%) of which were considered comprehensive cancer centers. There was a total of 4616 physicians, of which 84.3% were oncologists, 10.6% were hematologists-oncologists, and 5.1% were classical hematologists. The median number in descending order of physicians, oncologists, general hematologist-oncologists, and classical hematologists per center were 55 (range, 16-275), 45 (range, 12-270), 5 (range, 0-48), and 3 (range, 0-13), respectively (Figure 1A). The median proportions of classical hematologists and physicians practicing CH (general hematologist-oncologists plus classical hematologists) were 5.1% (range, 0-20.0) and 14.9% (range, 0-55.6), respectively. There were 12 HFFTPs (18.8%) within NCI-designated cancer centers. Most (11/12) centers with HFFTPs had >50 physicians and ≥5% classical hematologists; 11 centers with similar characteristics did not have an HFFTP (Figure 1B). Centers with HFFTPs had significantly higher numbers of physicians (median, 95.0 [range, 38-185] vs 49.5 [range, 16-275]; P = .001) and classical hematologists (median, 6.0 [range, 3-13] vs 2.0 [range, 0-11]; P < .001) but similar proportions of classical hematologists (median, 6.0% [range, 3.8-13.5] vs 4.5% [range, 0-20.0]; P = .078) and physicians practicing CH as part of their clinical practice (median, 12.3% [range, 6.5-47.7] vs 15.7% [range, 0-55.6]; P = .402) compared with those without HFFTP (Tables 1 and 2).

Adult hematology-oncology physician workforce by subspecialties per NCI-designated cancer center. (A) The number and proportion of physicians by subspecialty. (B) The proportion of classical hematologists in cancer centers with and without an HFFTP. Red bars represent centers with HFFTPs, whereas black and yellow circles indicate the percentage of classical hematologists in each respective training program.

Adult hematology-oncology physician workforce by subspecialties per NCI-designated cancer center. (A) The number and proportion of physicians by subspecialty. (B) The proportion of classical hematologists in cancer centers with and without an HFFTP. Red bars represent centers with HFFTPs, whereas black and yellow circles indicate the percentage of classical hematologists in each respective training program.

Total number of physicians and number of classical hematologists in cancer centers with and without an HFFTP

| Cancer centers (n) . | Total number of physicians . | Number of classical hematologists . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P value . | Median (range) . | P value . | |

| With HFFTP (12) | 95.0 (38-185) | .001 | 6 (3-13) | <.001 |

| Without HFFTP (52) | 49.5 (16-275) | 2 (0-11) | ||

| Cancer centers (n) . | Total number of physicians . | Number of classical hematologists . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P value . | Median (range) . | P value . | |

| With HFFTP (12) | 95.0 (38-185) | .001 | 6 (3-13) | <.001 |

| Without HFFTP (52) | 49.5 (16-275) | 2 (0-11) | ||

Percentage of classical hematologists and percentage of classical hematologists combined with hematologists-oncologists in cancer centers with and without an HFFTP

| Cancer centers (n) . | Classical hematologists, % . | Classical hematologists and hematologists-oncologists, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P value . | Median (range) . | P value . | |

| With HFFTP (12) | 6 (3.8-13.5) | .08 | 12.3 (6.5-47.7) | .4 |

| Without HFFTP (52) | 4.5 (0-20.5) | 15.7 (0-55.6) | ||

| Cancer centers (n) . | Classical hematologists, % . | Classical hematologists and hematologists-oncologists, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P value . | Median (range) . | P value . | |

| With HFFTP (12) | 6 (3.8-13.5) | .08 | 12.3 (6.5-47.7) | .4 |

| Without HFFTP (52) | 4.5 (0-20.5) | 15.7 (0-55.6) | ||

Our study provides an estimate of the CH workforce in the United States. Among adult hematologist-oncologists at NCI-designated cancer centers, only 1 in 20 are classical hematologists, although 1 in 7 have CH as part of their practice. The proportion of classical hematologists at these centers is consistent with a previous survey of hematology-oncology fellows, which found that only ∼5% planned to specialize in CH.2,4 Although virtually all NCI-designated cancer centers have classical hematologists, we do not know the proportion of referrals that pertain to CH. A study from 1 NCI-designated cancer center demonstrated that 40% of its ∼5000 annual referrals were for CH consultations. Most of these consultations were being managed by general hematologist-oncologists rather than classical hematologists.7 Similarly, a 2022 survey of >1200 ASH member physicians revealed that, on average, 30% of their patient care time was devoted to CH.8 Centers with HFFTPs have a higher number, but a similar percentage, of classical hematologists than those without HFFTPs. The higher number likely reflects that centers with HFFTPs are generally larger institutions, requiring a critical mass of CH cases and physicians to support such a program. The similar percentage suggests that most centers, with or without HFFTPs, encounter a comparable proportion of CH consults. Taken together, these data present a compelling argument for more classical hematologists in the workforce.

CH as a discipline has become increasingly more complex. It encompasses a broad number of unrelated blood disorders both established (bleeding, clotting, hemoglobinopathy, immune cytopenia, and thrombotic microangiopathy, to name a few) and emerging (eg, clonal cytopenia and VEXAS [vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X linked, autoinflammatory, somatic] syndrome). Furthermore, just in the last 6 years, CH has gained close to 50 new US Food and Drug Administration drug approvals, ranging from novel therapies for rare disorders to genetic therapies for hemophilia and hemoglobinopathies.9 The ASH’s recent support in the development of HFFTPs, with a goal of producing 50 new academic classical hematologists by 2030, is a recognition of this reality and an acknowledgment of the demand for classical hematologists.6 Although this is a good starting point, it will not be sufficient to meet the burgeoning CH workforce shortage. Given the complexity and rapid scientific discoveries in CH, we believe establishing more hematology-only pathways within already-supported hematology-oncology fellowships training programs may become essential.

Our study has several limitations. The physician classification relied on the profiles displayed in the institutional website. These profiles may not have been updated or be totally accurate, and likely reflect outpatient practices. There are a couple of hematology-oncology fellowship programs in the country allowing a hematology-focused track that are outside of the ASH HFFTP consortium or not within NCI-designated cancer centers. These programs may not have been included in our study. What constitutes the scope of practice for a classical hematologist may vary according to the institution. We followed the World Health Organization definitions for malignancy and considered acquired clonal disorders that are noninvasive as CH conditions. Therefore, monoclonal gammopathy and clonal cytopenias of undetermined significance were considered CH conditions, whereas polycythemia vera and essential thrombocytosis were not. We also acknowledge that there are going to be situations in which classical hematologists will be seeing malignant conditions, for example, during the hospital consult service.

The ASH’s HFFTP model can likely be recreated by several larger existing hematology-oncology fellowship programs within NCI-designated cancers. Based on our study, centers selected to participate in the ASH HFFTP are generally larger with ≥50 hematology-oncology–trained physicians and >5% classical hematologists. At least 7 other centers have similar characteristics. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for NCI-designated cancer centers without an HFFTP to encourage their general hematologist-oncologists to subspecialize or focus on CH. Lack of mentorship has been consistently recognized as a substantial contributor to the low numbers of classical hematologists.4,5 Conversely, pilot programs of long-term mentorships translate into a greater number of classical hematologists.10 Collectively, these measures may help further alleviate the shortage in the CH workforce and expand CH mentorship for fellows.

Acknowledgments: This project was supported by the generosity of the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Family Foundation and Kenneth G. Mann.

Contribution: J.P.A., Lewis T. Go, Lucas T. Go, M.D.S.K.G., and R.S.G. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; A.P.W.-S., A.A.A., M.A.E., R.L.G., C.C.H., L.J.P., R.K.P., C.E.R., R.L.R., S.S., M.E.S., M.A.S., M.S., and E.M.W. critically appraised the manuscript and reviewed the data; and all authors approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jithma P. Abeykoon, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; email: abeykoon.jithma@mayo.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented, in part, in an abstract form at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Jithma P. Abeykoon (abeykoon.jithma@mayo.edu).