Visual Abstract

Clinical trial design for classical hematologic diseases is difficult because samples sizes are often small and not representative of the disease population. The American Society of Hematology initiated a roadmap project to identify barriers and make progress to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion into trial design and conduct. Focus groups of international experts from across the clinical trial ecosystem were conducted. Eight issues identified include (1) harmonization of demographic terminology; (2) engagement of lived experience experts across the entire study timeline; (3) awareness of how implicit biases impede patient enrollment; (4) the need for institutional review boards to uphold the justice principle of clinical trial enrollment; (5) broadening of eligibility criteria; (6) decentralized trial design; (7) improving access to clinical trial information; and (8) increased community physician involvement. By addressing these issues, the hematology community can promote accessible and inclusive trials that will further inform research, clinical decision-making, and care for patients.

Many classical hematologic diseases fall under the classification of rare or orphan diseases because they affect <200 000 Americans (60/100 000 individuals) or have a low prevalence of <5 per 10 000 per the European Union or <6.5 to 10 in 10 000 globally according to the World Health Organization.1 The small population size, poorly understood natural history, biases in health care, lack of inclusion of underrepresented populations, limited access to research, and lack of defined clinically meaningful outcomes make enrollment of diverse patient populations into trials for these diseases challenging.2 These characteristics also pose unique hurdles to feasible, scientifically sound, and efficient trial implementation. Furthermore, clinical trials for these rare diseases are encumbered by methodological limitations, warranting novel approaches for trial design and statistical analysis. As a result, integrating diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in trials with small patient populations require special consideration and innovative solutions for trial conduct and patient recruitment.1,3

To ensure that hematology trials are diverse (ie, reflective of the epidemiology of the disease under investigation and inclusive of different sex, gender, racial and ethnic groups, age groups, and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations4), the American Society of Hematology (ASH), by virtue of its strong commitment to DEI,5 decided to embark on a multipronged approach, which began with engaging various stakeholder groups to tackle these challenges. Under the auspices of its Subcommittee on Clinical Trials, ASH undertook an initiative aimed at increasing diversity in and overall access to clinical trials for people living with classical hematologic disorders (eg, hemophilia, thalassemia, and sickle cell disease, etc). This initiative was titled as follows: the roadmap to improve DEI in hematology clinical trials (“roadmap”).

Strategy

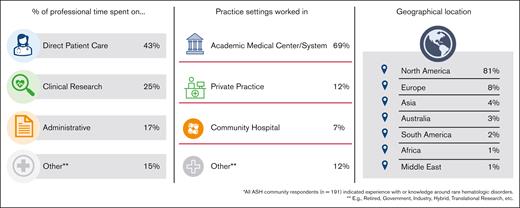

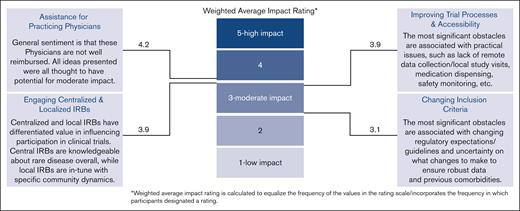

The convening power of ASH was leveraged to conduct a systematic assessment of DEI in classical hematology clinical trials using a combination of surveys and focus groups. A baseline view of the current state was obtained through a quantitative survey of the membership (Figure 1). A total of 191 ASH members who self-identified as caring for individuals with classical hematologic diseases responded to the survey (supplemental Data, survey 1). Survey responses identified a number of obstacles to overcome and revealed details of the impact of underrepresentation in trials as well as the complexity of the challenges to be overcome (Figure 2). A cumulative analysis and prioritization of the survey outcomes were then used to frame activities for subsequent focus group sessions.

ASH survey demographics. Depicts the characteristics of the 191 ASH member survey participants focused on classical hematologic diseases. Survey participants reported how they spent their professional time, the practice setting they worked in, as well as their geographical location.

ASH survey demographics. Depicts the characteristics of the 191 ASH member survey participants focused on classical hematologic diseases. Survey participants reported how they spent their professional time, the practice setting they worked in, as well as their geographical location.

Summary of survey results. As expected, diversity in clinical trials is low, and accessibility is difficult. Of the 4 topics included in the survey, increasing support for practicing physicians outside of academic medical centers was deemed as an opportunity for most impact.

Summary of survey results. As expected, diversity in clinical trials is low, and accessibility is difficult. Of the 4 topics included in the survey, increasing support for practicing physicians outside of academic medical centers was deemed as an opportunity for most impact.

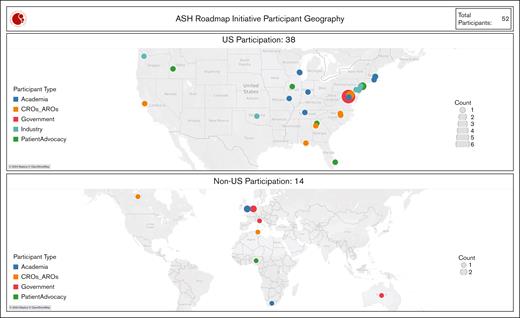

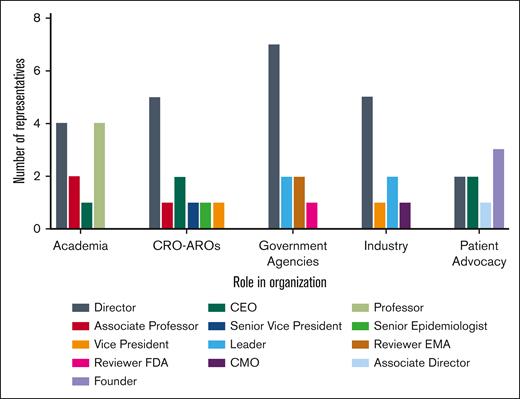

After the survey and recognizing that the challenges to clinical trial participation are shared by all stakeholders involved in the clinical trial enterprise, ASH convened 5 international focus groups (Figure 3), engaging individuals who are responsible for or involved in the conduct of clinical trials from inception to conclusion and in a position to enact change (Figure 4). These focus groups comprised the following: (1) people living with classical hematologic diseases and their advocates; (2) academicians; (3) regulatory and government agencies; (4) industry representatives; and (5) clinical research organizations and academic research organizations.

Geographic representation of focus group participants. A heat map displaying the United States and worldwide locations of focus group participants. The circle size increases with the number of individuals represented. AROs, academic research organizations; CROs, clinical research organizations.

Geographic representation of focus group participants. A heat map displaying the United States and worldwide locations of focus group participants. The circle size increases with the number of individuals represented. AROs, academic research organizations; CROs, clinical research organizations.

Depiction of the leadership roles each focus group participant holds within their respective organization. CEO, chief executive officer; CMO, chief marketing officer; EMA, European Medicines Agency.

Depiction of the leadership roles each focus group participant holds within their respective organization. CEO, chief executive officer; CMO, chief marketing officer; EMA, European Medicines Agency.

Each group was made up of ∼10 individuals who participated in independent virtual sessions that generated a list of priority topics, including a list of barriers to integrating DEI in hematology clinical trials.

An initial recommendation from these groups was to engage nonacademic physicians, primarily those working in community settings. Thus, a survey of 900 ASH physicians who devote >75% of their time to clinical practice and care primarily for people living with classical hematologic diseases was conducted to better understand barriers to participation of patients cared for outside of academic medical centers (supplemental Data, survey 2). Although the complete response rate to this survey was only 3%, the feedback from it, along with the quantitative survey referenced in supplemental Data survey 1, informed subsequent discussions and recommendations that were developed by the focus groups.

Summary of findings

This initiative highlighted the following barriers across the groups that, when addressed, will enhance the development of trials with diverse populations of people living with classical hematologic diseases (Table 1).

Harmonization of demographic terminology and data collection is lacking.

Summary of clinical trial barriers deemed by all stakeholder groups as opportunities for the most impact if addressed (not in rank order)

| 1 | Harmonization of demographic terminology and data collection is needed. |

| 2 | Engagement of LEEs from study inception to dissemination of results and through regulatory assessment is needed. |

| 3 | Implicit biases continue to impede patient enrollment. |

| 4 | IRBs need to uphold the justice principle, which is part of their mandate. |

| 5 | Eligibility criteria should not exclude important groups. |

| 6 | DCT options can improve inclusion. |

| 7 | Limited access to trial information. |

| 8 | Community physicians often are not engaged in the clinical trial ecosystem. |

| 1 | Harmonization of demographic terminology and data collection is needed. |

| 2 | Engagement of LEEs from study inception to dissemination of results and through regulatory assessment is needed. |

| 3 | Implicit biases continue to impede patient enrollment. |

| 4 | IRBs need to uphold the justice principle, which is part of their mandate. |

| 5 | Eligibility criteria should not exclude important groups. |

| 6 | DCT options can improve inclusion. |

| 7 | Limited access to trial information. |

| 8 | Community physicians often are not engaged in the clinical trial ecosystem. |

It has long been recognized that clinical trial participants should reflect the population for which the health product is intended.6 This is important because biological, social, and other variables can affect the way a health product functions in different populations, potentially resulting in different safety and/or efficacy profiles. To test for potential differences, trial populations should be diverse. This ensures that the estimated treatment effect is generalizable to those living with the disease and that there are disaggregated data for meaningful subgroup analyses. Although this can be challenging to achieve in rare hematologic diseases, the data in aggregate should represent the demographics of the population affected by the condition or disease. Trials of investigational products can be supplemented by pragmatic trials and postmarket surveillance after approval, when the approved therapy is accessible to the general population, and additional information on the safety and efficacy of said therapy in diverse populations can be collected. Two main issues must be addressed to appropriately capture and analyze trial data in a disaggregated manner:

Collection of demographic data: requirements for the collection of demographic data for clinical trials are not internationally harmonized. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance in 2016 (updated draft guidance released in 2024) on the importance of using standard terminology when collecting data on race and ethnicity.7 Health Canada has draft guidance outlining recommendations for collecting disaggregated data,8 whereas in Europe, although the responsibility for clinical trials lies with the individual European countries, the European Medicines Agency is working on several initiatives through Accelerating Clinical Trials in the EU.9 Most trials collect demographic information on participants (sex, age, and race/ethnicity), but the data collected can change from trial to trial and across jurisdictions and are often not used for end point analysis. Furthermore, potentially important demographic data are often not collected (eg, gender and socioeconomic status, etc). Although safeguarding patients' privacy is of utmost importance (reference is made to the General Data Protection Regulation [Regulation (EU) 2016/679), having adequate and complete demographic data on the patient population included in the clinical trial will help in understanding the external validity. This information can help determine how accurately clinical trial results represent benefits and risks when used in a wider population.

Demographic data terminology: internationally harmonized terminology for participant demographic data is lacking. Examples include the following:

The terms sex (biological variable) and gender (social construct) are often used interchangeably, despite having different meanings.

There is no standardized approach to classify life stages (eg, prenatal/infancy, early childhood to adolescence, and adulthood to aging) with clear and consistent age bands, similar to those defined in publications regarding drug evaluation in older adults4 and in the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidance E7 Studies in Support of Special Populations: Geriatrics10 for the older population.

Population descriptors inclusive of ascribed race/ethnicity data collected in trials are not consistent globally, making data analysis across multiple jurisdictions or multiple studies difficult. Often, race/ethnicity data are collected based on the categories required by the FDA (Latino/Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and White), which do not represent global populations. That said, it is worth noting that the FDA’s approach to race/ethnicity is based on the US Office of Management and Budget Statistical Policy Directive No. 15.

The lack of a harmonized or interoperable approach creates significant challenges for both industry and regulatory agencies because clinical trials are frequently developed for broad populations. Internationally harmonized demographic terminology or the establishment of an international agreement fostering the interoperability of data collection in clinical trials will enable appropriate analyses between and within populations of interest, including intersectional analyses. This, in turn, will lead to better regulatory decisions and provide more accurate information regarding the safety and efficacy of health products for people living with classical hematologic diseases. Furthermore, harmonized terminology is not only a goal itself but also a necessary step toward establishing crossgeographic representation, such that data collected in 1 demographic in “region A” can be generalized to represent the people of the same demographic in “region B.”

To realize a globally harmonized approach for demographic data collection and terminology in clinical trials, it is imperative that all key groups involved work collaboratively. First, all parties must collaborate to support the increased representation of traditionally underrepresented populations in the health product development process. Regulators have been supporting this work for some time through guidance development, recommendations/requirements for clinical data to be disaggregated, and transparency initiatives that provide information on the demographic breakdown of trial results used for regulatory decisions. For example, in 2022, the FDA implemented a requirement for the submission of a diversity plan11 to improve diverse representation in phase 3 clinical trials. Regulators and sponsors should now work in partnership toward globally harmonized data collection requirements for patient demographic data, as well as harmonized terminology that is globally acceptable. This work would benefit from input from trial participants, especially those from populations who tend to be underrepresented in clinical trials. Such a global effort may be best suited for the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.

Lastly, regulators recognize that creating guidelines and achieving goals related to increasing diversity in clinical trials are more difficult for rare diseases. When it is not possible to include diverse participants in trials (because the population suffering from the disease/condition is too small or biologically confined [eg, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome]), plans should be made to continue collecting real world data to enable the collection of safety and efficacy data by population over time.

Engagement of lived experience experts (LEEs) from study inception to dissemination of results and through regulatory assessment is needed.

Community engagement is a cornerstone for achieving diversity and equity in clinical trials, ensuring representativeness (eg, who is in the room) and inclusivity (eg, whose voice is heard). Connecting with communities through active engagement, collaboration, and transparent communication builds trust. A crucial component of community-engaged research is a reciprocal relationship in which the clinical trial provides meaningful value to the community of interest. LEEs, that is, people living with classical hematologic diseases, their caregivers, and family members directly affected by the disease,12 should be part of the research team and provide input from study inception through to dissemination of results. This is important because of the following:

Their insight helps identify meaningful trial objectives and end points that will most affect disease outcomes from the lived perspective.

They can help foster the development of higher quality data collection by pinpointing barriers to trial participation (eg, financial, childcare, and transportation, etc) and by being educators and advocates for the study.

They can support investigators and trial sites with study-related procedures to enhance recruitment and retention of participants.

They can help in disseminating data, because their role in describing study outcomes should be accepted and valued, leading to greater implementation of the findings into clinical practice and community benefit.

Effective community engagement requires strategic inclusion of community sites in clinical trials, building a study team that is truly part of that community, and acknowledging the contributions of the LEEs.13 This can be challenging to accomplish. However, the goal should be to develop a cadre of well-informed LEEs, who become meaningful partners in the research enterprise and community ambassadors to enhance patient-centered research. One example of this is the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Ambassador Program.14

The role of the LEE in helping to design and optimize the output of the clinical trial should be recognized and respected based on their unique and important perspectives.13 To this end, they should be appropriately compensated for their time and efforts. Researchers should include a budget allocation for community engagement when they are putting together their proposal or grant submission for the research.

A critical part of community engagement is ensuring that patients participating in the trial are supported (financially and emotionally) throughout the trial process. This is a relatively simple aspect that, if addressed, will bolster diversity in trials. Patients participating in clinical trials (especially those from low socioeconomic backgrounds) can experience significant hardships in their trial journey (eg, lost wages, transportation costs, and identifying childcare, etc). There are also hidden or unknown costs of trial participation, such as copays for drugs or procedures during the trial. Solutions such as upfront expense payments, reimbursement for lost wages, robust transportation, and concierge services and ensuring that payers subsidize some of these hidden patient costs will improve diversity in trials.

In sum, LEEs should be trusted and valued partners in every aspect of a clinical trial, including setting priorities, assisting with study design and implementation, data analysis and interpretation, and dissemination of results. As such, they are respected members of the trial team, providing insights and oversight along the entire research continuum.

Implicit biases continue to impede patient recruitment and enrollment.

Patient enrollment in clinical trials is often a complex process that begins well before a patient is approached to consider participating. Perhaps, the most important barrier to trial participation is physician perception. Physicians should not assume that certain groups are not interested in research15; rather, they should examine how the clinical trial system filters out patients and enables selection bias. Some physicians have developed relationships with patients and/or have historical context that leads to assumptions about the patient’s openness, willingness, and presumed ability to be a successful clinical trial participant. These impressions may be accurate, inaccurate, or forced upon the patient due to social determinants of health that have influenced their ability to fully access and be compliant with care. All patients should be presented with the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial. Language barriers should be minimized by translating consent forms and clinical trial materials. Trials should be designed with offerings that meet the needs of all patients and fill the gaps that historically have prioritized the enrollment of socioeconomically advantaged patients.

Patients should be given the support and tools necessary to successfully participate in trials. These tools begin with the physician-patient relationship, which allows for bidirectional communication about the opportunity and commitment associated with participation in research. Conversations should include the potential barriers to participation and support that can decrease or eliminate these barriers. As mentioned prior in this article, support could include, for example, decreased travel to local office visits, home visits, shipped trial medications, financial support for travel or missed work, as well as out-of-pocket expenses incurred due to study visits and interventions.

Ethics committees and institutional review boards (IRBs) need to uphold the justice principle that is part of their mandate.

IRBs are founded on 3 guiding principles from the Belmont report: (a) respect for persons, (b) beneficence, and (c) justice.16 They have traditionally focused on protecting patients from risk and harm; however, there is a need for them to also focus on the principle of justice that stipulates the importance of fair selection of study participants.16 In Europe, the Guide for Research Ethics Committee Members developed by the Council of Europe’s Steering Committee on Bioethics notes that research involving human beings should be conducted according to ethical principles, which are universally recognized, including autonomy, beneficence and nonmaleficence, and justice. An IRB or research ethics committee’s failure to focus on the justice guiding principle may lead to the exclusion of underrepresented individuals from trials. In addition, data regarding IRB membership indicate that they often lack diversity.17 So, an important first step in making IRBs part of the diversity solution is to make them representative of the communities they serve.

IRBs should be an important ally in driving diversity. By engaging the perspectives of LEEs, they could effectively hold principal investigators accountable for the design of inclusive trials that will lead to diverse enrollment at their sites.18 Although local IRBs often have knowledge of the geographic community and culture, deferring review and approval to a single, centralized IRB with experience in rare diseases can ease administrative burden and decrease the time to trial initiation. Working collaboratively, central and local IRBs can (a) ensure that all exclusion criteria are ethically, scientifically, or medically justified; (b) demand translation and interpreter services when appropriate; (c) demand participant and caregiver reimbursement and compensation at a fair and equitable level; (d) consider posttrial responsibilities of the participant; (f) review participant access to individual results; and (g) mandate the return of aggregate results to the participant and community in a timely way. In sum, the IRB can warrant that recruitment and retention processes are tailored to the community and are culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Eligibility criteria should not exclude important groups.

Clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria often unnecessarily limit the enrollment of populations that are chronically underrepresented in clinical trials, even when that population is expected to use or benefit from the health product being tested (eg, older populations, pediatric populations, certain racial and ethnic populations, pregnant/lactating people, and patients with certain comorbidities).19,20 Eligibility criteria are designed to maximize estimates of efficacy and safety; however, a “protection by exclusion” approach that excludes patients who may potentially experience adverse effects can put them at greater risk when the health care product is approved, because they may be prescribed the product without full knowledge of its safety and efficacy in their particular circumstance.21-23

Government agencies such as the FDA, National Institutes of Health, Health Canada, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, and European Medicines Agency are supportive of broadening inclusion criteria so that trial participants are representative of patients in the real world who will benefit from that health product.10,24,25 Therefore, exclusion criteria should be critically reviewed to (a) confirm that they are necessary and (b) determine how they will affect the enrollment of unrepresented populations. Published justification schemes for exclusion criteria can serve as a guide.26 If certain patient groups cannot be enrolled for safety concerns, post approval collection of data should be planned and analyzed.

Decentralized clinical trial options can improve inclusion.

Decentralized trials (DCTs) have the potential to allow for broader and more diverse clinical trial participation. However, there are potential drawbacks. Specifically, if DCTs rely heavily on technology, it could represent a digital barrier for older, rural, and underrepresented racial and ethnic populations who may not have access to or familiarity with the Internet, smart phones, and tablets, etc. On the contrary, face-to-face visits may disproportionally burden patients who have caregiving responsibilities or those of lower socioeconomic status. Careful consideration needs to be given to the implementation of DCTs, including options for virtual participation, remote data collection that leverages technology, and electronic health or registry records,.27,28

Limited access to trial information.

An important component of diversity solutions, especially for rare hematologic diseases, is access to robust, reliable epidemiological and patient-level diversity data. The lack of these data within and outside the United States is a barrier to achieving diversity in clinical trials. Establishing national and global standards for self-identification may help solve this problem.

Social media is 1 of the primary ways people seek out information. Therefore, it is important for researchers to leverage digital platforms, when appropriate, to engage in patient communities. Working with advocacy groups and digital thought leaders who have significant social media presence can help disseminate research information in patient-friendly language to broad groups, thereby improving clinical trial awareness, interest, and enrollment.

Community physicians often are not engaged in the clinical trial ecosystem.

Diverse enrollment for rare diseases requires (a) strategic engagement of community physicians and (b) trial design models that can be implemented at local community centers, where trial processes are completed either as an extension of a research center or as a research site themselves.

To accomplish this effectively, trial sponsors should aim to raise awareness about their trials to community physicians, by developing plain language versions of the protocol and creating trial-specific educational resources. Such resources help build understanding around the rationale for all elements of the trial design and inform the community physician’s decision as it relates to offering a trial to their people living with classical hematologic diseases.

Regarding creating innovative trial design models that engage local community centers, it is true that bureaucratic burdens, challenging logistics, and safety monitoring requirements for participating in trials (especially in rare indications in which only 1 patient may be enrolled) create challenges for community centers to be engaged. To that end, stakeholders must invest in the development of research infrastructure at local sites or community centers, including staff training around all aspects of trial conduct, educational resources, and other forms of site support. Communication, interventions, and care should be offered with cultural humility and sensitivity.29 Appropriate compensation and recognition for the participation of local physicians and staff are also critical.

Lastly, investing in a diverse work force at community centers as well as diverse investigators and staff, who speak different languages and have experience in recruiting diverse trial participants, will go a long way in addressing this gap.

Conclusion

ASH recognizes the need to address social and systemic inequities that are pervasive in every aspect of society including clinical trial design, enrollment, and outcomes and is committed to working toward a more equitable and just health care system.5 The opportunity to participate in clinical trials should be universal, because the data from accessible and inclusive trials can better inform decision-making about the management of hematologic disorders. This is why ASH’s Subcommittee on Clinical Trials has prioritized enhancing access and enrollment into hematology clinical trials for underrepresented populations.

Addressing the barriers noted here extends beyond 1 key group or 1 trial, which is why partnering across LEEs, industry, regulators, academia, IRBs, and health care providers is essential. What are the must dos? A holistic overview of the patient's experience and disease demographics needs to be collected and discussed. Relevant LEEs and health care providers should be engaged early and often as research questions are crafted and clinical trials are designed. The insights from such engagement would include social determinants of health, reasons for mistrust, and health care access barriers. Rare classical hematology disease trials should seek to be inclusive through representative inclusion/exclusion criteria that are further evaluated for the impact of increased heterogeneity on the robustness of small data sets, end points that matter to patients, and ways to reduce participation burden on patients so that diversity can be achieved.

It is important to meet patients where they are, invest in education and awareness, build trust, and work with partners to identify and support credible messengers in the communities. Furthermore, decentralized community-based trial designs can help increase trial accessibility but could amplify the infrastructural complexity and costs associated with the recruitment of geographically dispersed rare disease populations. These unique challenges notwithstanding, ASH recognizes that optimizing DEI in the study of rare diseases will benefit all clinical hematology trials and will prioritize the development of unique resources to address these issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors constitute a subgroup of the participants in the roadmap to improve DEI in hematology clinical trials and, to that end, acknowledge their peers for their dedication and contribution to the overall initiative and for their continued commitment to fostering DEI in clinical trials: Allison A. King (Washington University in St. Louis), Amy D. Shapiro (Indiana Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center), Lynn M. Malec (Medical College of Wisconsin), Johnny Mahlangu (University of the Witwatersrand and National Health Laboratory Service Johannesburg), Patrick McGann (Hasbro Children’s Hospital), Pratima Chowdary (University College London), Barbara Kroner (Research Triangle Institute International), Brian Abbott (Brown University), Gloria Kayani (CYTE Global), Grier Page (Research Triangle Institute International), Karen Pieper (Thrombosis Research Institute), Pierre Brichot (Monitoring Consulting Tunisia-Clinical Research Organization), Rachael Fones (IQVIA), Ann Farrell (US Food and Drug Administration), Carrie Diamond (National Institutes of Health), Christine Lee (Australian National University), Julie Panepinto (National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), Sotirios Michaleas (European Medicines Agency), Qing Xu (US Food and Drug Administration), Richardae Araojo (US Food and Drug Administration), Tanya Wroblewski (US Food and Drug Administration), Ahmed Daak (Sanofi), Kimberly Nettles (Johnson & Johnson), Lisa Lewis (Janssen Research and Development), Savita Nandal (Novartis), Stephanie Christopher (Pfizer), Bukola Bolarinwa (Sickle Cell Aid Foundation), Jeanette Cesta (von Willebrand Disease Connect Foundation), and Lakiea Bailey (Sickle Cell Consortium). The authors thank the American Society of Hematology (ASH) staff Kelly Rose and Duong Nguyen for their assistance with creating some of the figures and Luminous LLC for facilitating the focus group sessions. Finally, the authors thank ASH and its Subcommittee on Clinical Trials for supporting this initiative.

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the regulatory agency/agencies or organizations with which the author(s) is/are employed/affiliated.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K., A.E.M., and S.S. conceived the idea for this initiative, led it from start to finish, organized surveys and focus groups, compiled and analyzed data, and led the writing of the manuscript; and all other authors participated in focus groups and writing groups that wrote initial drafts for different sections of the manuscript and also read and provided comments for multiple versions of the manuscript as it was being prepared.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.B. reports membership on a board or advisory committee for Clinithink, a technology company built around CLiX, a health care artificial intelligence capable of collating unstructured medical notes; consultancy fees from Lilly and Merck; and honoraria from Novartis. P.F. reports current employment and equity ownership (as a public stockholder) with Pfizer Inc. M.C.G. reports equity ownership (private company) with Absolutys, Dyad Medical, Fortress Biotech, and nference; consultancy fees from Angel/Avertix Medical, AstraZenca, Beren Therapeutics, Bioclinica, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Clinical Research Institute, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL) Behring, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Esperion, EXCITE International, Fortress Biotech, Gilead Sciences Inc, Inari, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Bayer, MashUp MD, MD Magazine, Merck, MicroPort, MJ Health, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Consortium, Pfizer, PhaseBio, Population Health Research Institute, PLx Pharma, Revance Therapeutics, Samsung, SCAI, SFJ, Solstice Health/New Amsterdam Pharma, Somahlution/Marizyme, Vectura, Web MD, and Woman As One; and research funding from CSL Behring, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Bayer, and Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Alliance. K.K. reports employment and equity ownership (public company) with Sanofi. A.E.M. reports research funding from Novo Nordisk and Pharmacosmos; and honoraria for serving on scientific advisory committee and membership on a board or advisory committee with Novo Nordisk. M.R. reports employment and equity ownership (public stock grants per company) with GlaxoSmithKline. J.C.R. reports consultancy fees from Genentech, HEMA Biologics, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; speakers bureau fees from Novo Nordisk, Takeda, and Sanofi; and research funding from Genentech and Takeda. S.S. reports employment with Novo Nordisk Inc; and equity ownership in Novo Nordisk Inc and Teva Pharmaceuticals. L.V. reports employment with National Hemophilia Foundation. H.V.S. reports research funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Heart and Stroke Foundation. A.P.W. reports membership on a board or advisory committee in Bayer, CSL Behring, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Takeda; and research funding from Octapharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alan E. Mast, Thrombosis and Hemostasis Program, Versiti Blood Research Institute, P.O. Box 2178, Milwaukee, WI 53226; email: aemast@versiti.org.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.