Key Points

Hematologic malignancies in the SAARC region pose a growing burden, with incidence and mortality varying across countries.

Disparities in health care infrastructure contribute to high MIRs and require regionally tailored strategies.

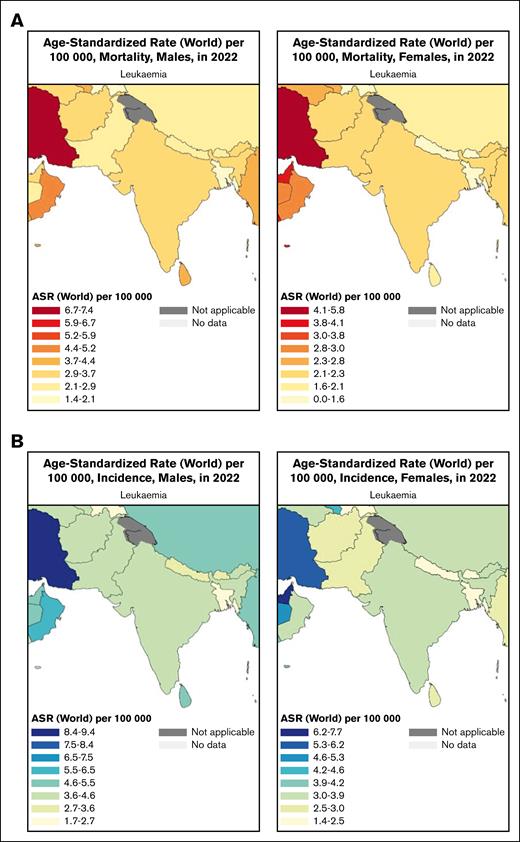

Visual Abstract

South Asia, comprising the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) nations, bears a disproportionately high cancer mortality relative to incidence. The epidemiology of hematologic malignancies, some of which are potentially curable with timely diagnosis and treatment, remains under explored in this region. We examined the burden, distribution, and future projections of hematologic cancers across SAARC countries to inform cancer control strategies. We used GLOBOCAN 2022 data from the Global Cancer Observatory and United Nations population estimates to assess incidence and mortality for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), leukemia, and multiple myeloma across SAARC countries. We report age-standardized incidence and mortality rates (ASIR/ASMR) per 100 000 individuals and mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs). Future projections to 2045 were estimated under the assumption of stable ASIR and ASMR. In 2022, 148 312 hematologic cancers were diagnosed in the SAARC region, including 63 448 cases of leukemia, 52 363 cases of NHL, 19 922 cases of multiple myeloma, and 12 579 cases of HL. India accounted for over three-quarters of all cases, followed by Pakistan. In terms of age-standardized incidence rates across both sexes, leukemia was the most common subtype, with the highest ASIR in Maldives (6.7 per 100 000 males) and the highest ASMR in Pakistan (3.4 per 100 000). In 2022, 30 582 deaths from NHL, 4645 deaths from HL, 17 199 deaths from multiple myeloma, and 46 671 deaths from leukemia occurred in SAARC. MIRs ranged widely from 0.52 (Sri Lanka; NHL) to 1.0 (Bhutan; multiple myeloma). By 2045, 236 000 new cases and 163 149 deaths are projected, with India bearing the greatest burden. These patterns may inform coordinated, equity-centered cancer planning and cancer system strengthening across SAARC nations to improve outcomes for patients with hematologic cancers.

Introduction

The global cancer burden is immensely heterogeneous.1 The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) includes the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka and is home to over 1.9 billion people, representing 24% of the world’s population.2 The SAARC region accounts for less than 10% of the 19.3 million new cancers reported annually, but this region broadly has a greater case-fatality rate than the global average.2,3

The SAARC region is diverse across cultures, health systems, and social determinants of health. For example, in India and Nepal, many continue to rely on traditional health care practices with systems such as Ayurveda and Siddha.4 In contrast, the importance of traditional medicine in Sri Lanka has substantially diminished over time.5 In India, the ratio of oncologists to patients with cancer is 1:1600, whereas in Sri Lanka, the ratio is 1:10 000.6 In Pakistan, 70% of the population lives in rural areas, but only 20% of health care facilities are located in rural settings.7

Hematologic cancers represent a unique cancer group due to potential for cure, prolonged disease control, and improved survival for many common disease entities, when diagnosed and treated effectively. Advances in diagnosis and treatment have led to remarkable survival outcomes in well-resourced countries, yet such progress has been unevenly distributed globally. Understanding the specific challenges and epidemiological patterns in underrepresented regions is essential to addressing disparities in care.

However, the burden of these cancers is poorly understood in South Asian countries,8 in part, due to the relatively low incidence and limited access to the infrastructure required to diagnose and treat these cancers. In this study, we describe and interpret the scale and profile of hematologic cancer incidence and mortality across the countries in the SAARC region, with the goal of informing efforts to develop targeted interventions that improve access to treatment and improve outcomes in this large and diverse region.

Data sources and methods

The estimated number of new cancer cases and deaths for the main hematologic cancer types (non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL], Hodgkin lymphoma [HL], multiple myeloma, and leukemia [a heterogeneous group including acute and chronic forms])9 was extracted from the International Agency for Research on Cancer's Global Cancer Observatory for the SAARC countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, by sex and the age group of 18 years. Corresponding population data for 2022 were extracted from the United Nations. We also report the age-standardized incidence (ASIR) and age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) per 100 000 individuals, the weighted average of the corresponding age-specific rates using the Segi-Doll world standard.10-14

The Global Cancer Observatory includes facilities for the tabulation and graphical visualization of the GLOBOCAN database, containing explorations of the current and future burden for 36 cancer types. The data sources and methods used in assembling these global estimates at the national level have been described in detail elsewhere, using the best available sources of cancer incidence and mortality data within a given country, or a suitable proxy. The data sources for the estimates on GLOBOCAN are shown in the supplemental Table.

GLOBOCAN also provides projections for 2045. These projections assume that ASIR and ASMRs remain constant through 2045 and do not account for potential changes in cancer risk, early detection, treatment, or survival. Therefore, these findings represent projected burden related to demographic changes.

Results

Overall, there were 52 363 diagnoses of NHL, 12 579 of HL, 63 448 of leukemia, and 19 922 of multiple myeloma across the entire SAARC region in 2022 (148 312 diagnoses). Stratifying by country, there were 2177 new diagnoses of hematologic cancers in Afghanistan, 7346 in Bangladesh, 31 in Bhutan, 115 396 in India, 42 in Maldives, 1456 in Nepal, 18 734 in Pakistan, and 2770 in Sri Lanka. Of the 4 groups of hematologic cancers, leukemia tends to be the most common hematologic cancer across the SAARC region.2 Most of these cases of leukemia stem from either India or Pakistan. NHL (representing a broad spectrum of diseases) was also significant in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, whereas multiple myeloma and HL generally were less common in the region.

NHL

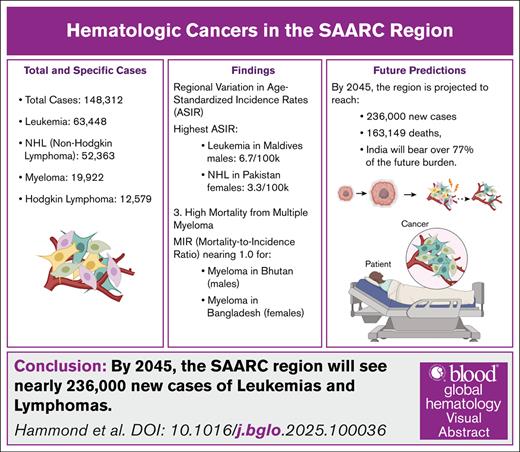

There were 52 363 new cases of NHL and 30 582 deaths from NHL in the region. The incidence rates were the highest in Maldives in males (ASIR = 6.1) and in Pakistan in females (ASIR = 3.3) and the lowest in Bhutan among males and in Bangladesh and Nepal among females (Table 1). The patterns were similar for mortality. Figure 1 shows the ASIRs and ASMRs of NHL among both males and females in the SAARC region. The MIR for females was the highest in Afghanistan (MIR = 0.78) and the lowest in Sri Lanka (MIR = 0.54). The MIR for males was the lowest in Sri Lanka (MIR = 0.52) and the highest in Afghanistan (MIR for females = 0.78).

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for NHL. (B) ASIRs among males and females for NHL.

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for NHL. (B) ASIRs among males and females for NHL.

HL

Across the SAARC countries, there was a 9611-fold variation and 50-fold variation in incidence and mortality rates, respectively, with 12 579 new cases and 4645 new deaths from HL. The highest incidence rate for HL was in Sri Lanka in females (ASIR = 0.73) and in Sri Lanka in males (ASIR = 1.2), whereas the lowest incidence rate was in Nepal in males (ASIR = 0.23) and in Bangladesh in females (ASIR = 0.19; Table 2). A similar trend was observed for mortality rates for HL, which are included in Table 2. Figure 2 shows the incidence and mortality rates of HL among both males and females in the SAARC region. MIR for females was the lowest in Sri Lanka (MIR = 0.27) and the highest in Afghanistan (MIR = 0.48). The MIR for males was the lowest in Sri Lanka (MIR = 0.29) and the highest in Afghanistan (MIR = 0.53).

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for HL. (B) ASIRs among males and females for HL.

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for HL. (B) ASIRs among males and females for HL.

Multiple myeloma

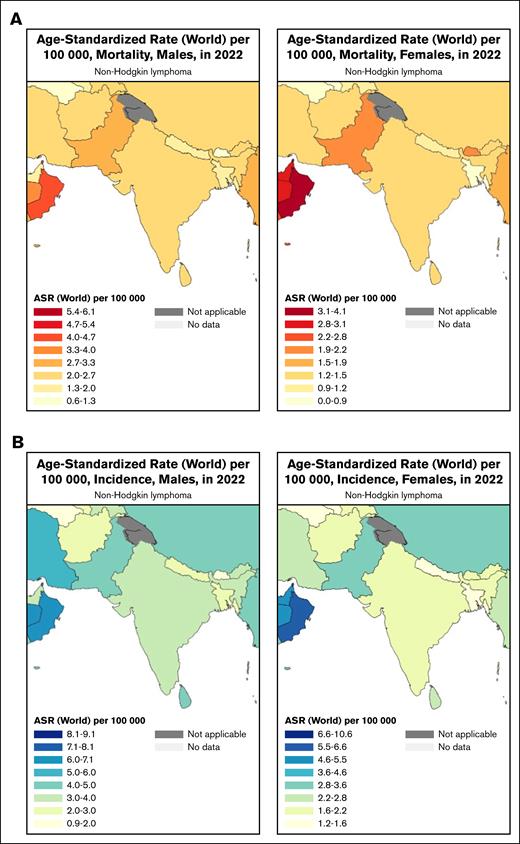

A total of 19 922 new cases and 17 199 new deaths from multiple myeloma were reported across SAARC countries. The incidence rates were the highest for multiple myeloma in males in Sri Lanka (ASIR = 1.9) and in females in Pakistan (ASIR = 1.1) and Sri Lanka (ASIR = 1.3). The lowest incidence rates for multiple myeloma was found in Bhutan (ASIR = 0.60), Nepal (ASIR = 0.53), Bangladesh (ASIR = 0.64) and Afghanistan (ASIR = 0.67) in males and in Bangladesh (ASIR = 0.37; Table 3) in females. Mortality rates for multiple myeloma had a similar trend to incidence rates, included in Table 3. Figure 3 shows the incidence and mortality rates of multiple myeloma among both males and females in the SAARC region. The MIR for the countries in SAARC for females ranges between 0.82 and 0.92, among which Afghanistan had the lowest MIR (MIR = 0.82) and Bangladesh had the highest MIR (MIR = 0.92). The trends were noted to be different in males where the MIR ranged from 0.84 to 1.0, with Sri Lanka having the lowest MIR (MIR = 0.84) and Bhutan having the highest MIR (MIR = 1.0).

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for multiple myeloma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for multiple myeloma. (B) ASIRs among males and females for multiple myeloma.

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for multiple myeloma. (A) ASMRs among males and females for multiple myeloma. (B) ASIRs among males and females for multiple myeloma.

Leukemia

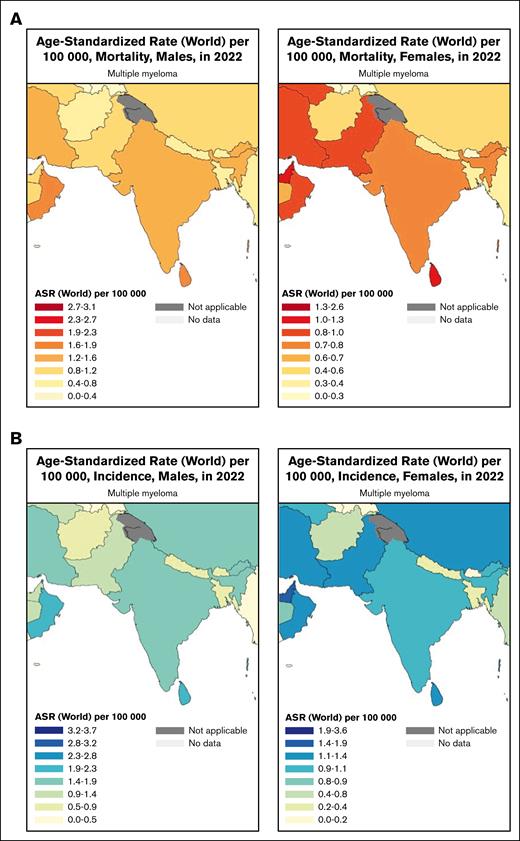

There were 63 448 new cases of leukemia and 46 671 deaths from leukemia in the region, with a 2494-fold variation and 3073-fold variation in incidence and mortality rates across SAARC countries, respectively. The highest incidence rates for leukemia were in Maldives (ASIR = 6.7) in males and in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (ASIR = 2.9) in females. Incidence rates were the lowest for multiple myeloma in Bangladesh (ASIR = 2.2) in males and in Bangladesh (ASIR = 1.4) and Maldives (ASIR = 1.8) in females. Mortality rates showed a similar pattern for SAARC countries. Leukemia ASMR was the highest in Maldives for males and high in India, Afghanistan, and Sri Lanka for females (ASMR of 4.3 in Maldives for males; ASMR of 2.2 in India for females; ASMR of 2.1 in Afghanistan for females; and ASMR of 2.1 in Sri Lanka for females; Table 4). Bangladesh had the lowest ASMR for leukemia for both males and females (ASMR of 1.6 for males and ASMR of 1.2 for females; Table 4). Figure 4 shows the incidence and mortality rates of leukemia among both males and females in the SAARC region. The MIR for females was the highest in Bangladesh (MIR = 0.86). Nepal had the highest MIR (MIR = 0.79) and Maldives had the lowest MIR (MIR = 0.64) for males.

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for leukemia. (A) ASMRs among males and females for leukemia. (B) ASIRs among males and females for leukemia.

Incidence and mortality rates in males and females in SAARC countries for leukemia. (A) ASMRs among males and females for leukemia. (B) ASIRs among males and females for leukemia.

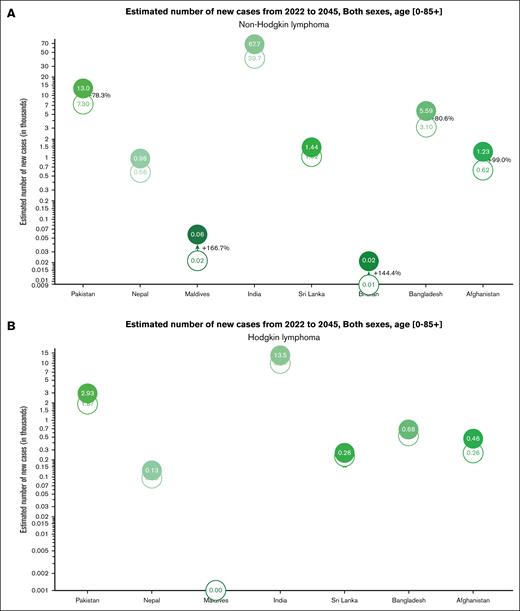

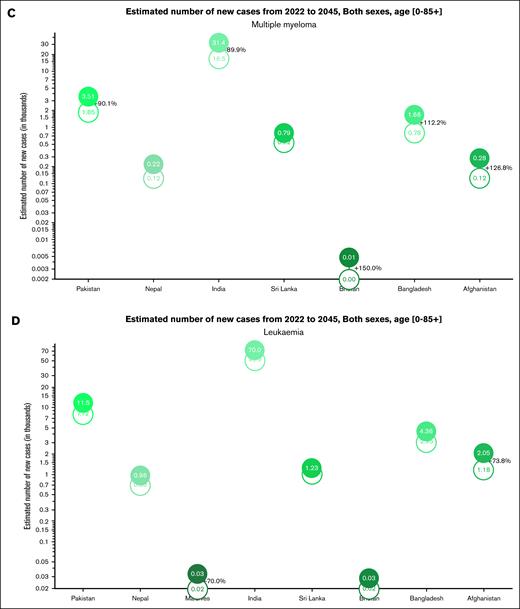

Future predictions

In the year 2045, assuming the 2022 ASIR and ASMR estimates remain unchanged, the SAARC region is projected to have close to 236 000 new diagnoses of hematologic cancers (Table 5). Across the 4 cancer groupings, India has consistently had the highest incidence for all 4 in the SAARC region and is estimated to have over three-quarters of the burden in the region, with 182 600 predicted patients in 2045 (Table 5). The projected incidence of hematologic cancers is the highest for leukemia and NHL regionally and nationally (Table 5). For example, the incidence of NHL and leukemia in Bangladesh is estimated to be 5590 and 4360 respectively, compared with an estimated incidence of 680 and 1660 for HL and multiple myeloma, respectively (Table 5). However, many countries (eg, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) show a greater proportional projected increase in the number of new diagnoses of multiple myeloma compared with the increase in NHL (Figure 5), with only Afghanistan and Maldives showing a predicted rise in the number of new diagnoses of leukemia (Figure 5). For the same year, a predicted 163 149 deaths from hematologic cancers will occur in the region (Table 5), with India having the highest number of new deaths 126 734 in 2045.

Discussion

Our study identifies several critical insights into the burden and disparities of hematologic cancers in SAARC countries. In 2022, there were an estimated 1 733 573 cancer diagnoses in the region, with 62 163 (3.59%) attributed to leukemia. India had the highest number of patients (48 419), followed by Pakistan (8305) and Bangladesh (2812).15 The highest incidence rates were noted in Pakistan (4.3 per 100 000) and Sri Lanka (4.1 per 100 000). The marked heterogeneity in hematologic cancer incidence across the region reflects diverse risk factors, health care access, and reporting systems. Furthermore, projections indicate that there will be a 50% increase in cancer-related deaths across the region by 2045, with Sri Lanka experiencing the steepest increases, reflecting the growing strain on health care systems in the region.16,17 The availability of critical diagnostic and treatment tools, such as flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, is severely limited in the region at present, leading to delayed diagnoses and underreporting.17 Geographic and socioeconomic disparities, such as limited health care centers in rural areas and high out-of-pocket costs, exacerbate health care inequities. Variability in cancer registry coverage and reliance on extrapolated data may partially obscure the true incidence of hematologic malignancies, particularly in resource-constrained settings with limited cancer surveillance systems such as Nepal and Bangladesh.

Our study revealed significant heterogeneity in the incidence and mortality rates of hematologic malignancies among SAARC countries. Notably, Bhutan and Nepal exhibited lower incidence and mortality rates across the hematologic subtypes, whereas Sri Lanka consistently presented with elevated rates. By 2045, the incidence and mortality rates of hematologic malignancies in SAARC countries are expected to rise markedly, with projections suggesting a 50% increase in cancer-related deaths region-wide. Sri Lanka, which currently has the highest rates of hematologic cancers at over 10 per 100 000 people, is expected to experience further rises, whereas Bhutan and Nepal, with current incidence rates of ∼2 to 3 per 100 000, are projected to face growing health care burdens due to population growth and limited access to specialized cancer care facilities.15 These findings underscore the variability in cancer burden within this region and suggest the influence of distinct health care systems, environmental factors, and public health measures.

The disparities in hematologic cancer outcomes across SAARC countries may be partially attributed to differences in health care systems, exposures and related predisposition to hematologic cancers, access to treatment, follow-up care, and the implementation of public health measures. Bhutan and Nepal, despite being resource-limited, appear to have lower incidence and mortality rates. This disparity may be linked to other competing causes of death or underdiagosis due to the limited diagnostic capabilities. Flow cytometry is critical to diagnosing many leukemias and may not be commonly available in the region. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) and CT imaging are needed for staging and treatment planning for many lymphomas. However, India has ∼3.6 CT scanners for every 1 million people, compared with 1 per 65 000 in high-income countries.18 In Bangladesh, the doctor-to-patient ratio stands at 1:2500, with only ∼20 positron emission tomography scanners available for the entire population.19

In Pakistan, limited diagnostic infrastructure, with only 10 pathologists per million people, further compounds the issue. Countries such as Bangladesh face a 30% gap in access to essential diagnostics, leading to poor cancer detection and treatment outcomes.20 Although Bhutan has implemented national screening programs for gastric, cervical, and breast cancers, further investment is needed for hematologic cancers.16,21 Moreover, a study on the health-related quality of life among 400 patients with blood cancer in Pakistan highlighted significant gaps in psychosocial support within the health care system.22 These findings point to the critical need for more comprehensive care models from diagnosis to treatment and prevention in resource-limited settings.

Across the SAARC region, there has been a general increase in the incidence of all hematologic cancers, although the growth rate is not uniform across cancer types. For instance, the increase is more pronounced for multiple myeloma and NHL than for leukemia.23 The varying rates of increase across different countries also point to potential differences in public health measures and health care infrastructure. For instance, India’s more prominent growth in cancer incidence rates compared with that of Maldives could be attributed to differences in public health policy on cancer screening programs and public health campaigns informing people on early warning signs of cancer or the availability of advanced diagnostic tools facilitating early detection.24

Pakistan is notable as the country with the highest incidence rate of both NHL and leukemia. The high incidence of NHL in males (ASIR = 4.9) and leukemia (ASIR = 4.3) may be a result of environmental risk factors prevalent in Pakistan, such as industrial pollution, pesticide exposure, and viral infections linked to lymphomas.25 In a meta-analysis involving 29 605 patients with cancer and 3 478 748 participants, NHL was the only cancer type that consistently showed a statistically significant link between dioxin exposure (both external and in blood levels) and cancer-related deaths.26 Another meta-analysis of 9587 patients diagnosed with NHL found a 33% higher relative risk among groups with high exposure and for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, a prominent subtype of NHL, the risk nearly doubled.27 The standardized mortality ratio for NHL was 1.18 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.37), indicating a modest but meaningful increase in risk.

Leukemia-related deaths totaled 45 707, with India (35 392), Pakistan (6261), and Bangladesh (2132) as the leading countries. Pakistan had the highest mortality rate (3.4 per 100 000), followed by Maldives (3.1 per 100 000). Such differences in mortality may arise due to variations in access to first-line diagnostics, limitations in the health care system delaying hematologic cancer-specific care, and limitations in the health care system delaying overall care. First, the paucity of expertise and resources in delivering first-line therapy remains a barrier in managing hematologic cancers across the SAARC region, further exacerbated by the scarcity of trained health care professionals, inadequate laboratory infrastructure, and the limited availability of advanced diagnostic tools.28,29 The shortage of diagnostic tools is clear in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with the median availability of diagnostics being 19.1% in basic primary care facilities.10 Addressing these deficiencies should be at the forefront of improving outcomes in patients with resistant infections.

Second, access to advanced treatments for hematologic malignancies, such as bone marrow transplant (BMT), biologics, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, and antibody-drug conjugates, remains limited in South Asian countries. For instance, in India, there are ∼70 BMT centers, which is relatively small given the country’s population.30 Of these centers, only ∼11 centers report data to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. In a similar vein, newer therapies such as CAR-T cell therapy, remain in early stages or are difficult to access despite showing promising results in treating relapsed cancers. One example is the collaboration of Tata Memorial Hospital and the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, which has initiated a CAR-T program, the countries’ first program aimed at modifying a patient’s T cells to tackle endogenous cancers. This therapy, approved in 2023, costs around $50 000, substantially lower than the $400 000 cost noted in US clinical trials. ImmunoACT, a spin-off company of the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, is set to produce the therapy, with plans to treat up to 1200 patients per year in India. This initiative aims to improve access to this emerging treatment, particularly for those in lower-income regions, offering a more affordable option compared with the high costs typically observed in other countries.31

Access to allogeneic stem cell transplantation, a curative option for hematologic malignancies, is limited in the SAARC region. India’s 70 BMT centers are insufficient, and treatment can cost upwards of $30 000, making BMT inaccessible to many. Likewise, Pakistan lacks donor registries, whereas Nepal and Bangladesh face infrastructure constraints.31 In Sri Lanka, higher incidence and mortality rates may exacerbate the present challenges in health care access, including long waiting times to visit specialists, unequal access for patients in rural areas, and limited treatment availability, such as dedicated radiation therapy centers.32 For instance, Sri Lanka has only 22 functioning megavoltage machines for a population of ∼22 million; these machines are concentrated in Colombo, which limits timely access to radiation for patients with cancer.33,34 Many of Pakistan’s numerous rural areas lack diagnostic facilities, leading to late-stage diagnoses that can also contribute to higher mortality rates.

The heterogeneity observed in hematologic cancer rates within the SAARC region is consistent with patterns found in other parts of the world. For example, studies in Europe and North America have also demonstrated marked variability in hematologic cancer incidence and outcomes, often linked to social determinants of health.35 Similar to the SAARC region, countries with robust health care infrastructure and comprehensive public health measures tend to have better outcomes and lower mortality rates.36 Notably, Japan has a life expectancy of ∼84 years, one of the highest in the world. Its cancer mortality rate is relatively low, with 5-year survival for all cancers estimated at 60%, compared with ∼50% globally.37,38

Limited health care resources and varying levels of medical infrastructure across the region contribute to the challenge of effectively addressing cancer. Nepal’s health care system relies on 52 000 community health volunteers to improve maternal and child health, but it faces significant shortages in specialized care in trauma surgery and mental health.39 Nepal also has a shortage of hematologists since hematology was not traditionally a part of the post-graduate training pathways in Nepal. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was rarely performed in Nepal due to financial constraints, and one of the few programs that do offer BMT was spearheaded in 2012.40 Mental health services receive less than 1% of the national health care budget, leaving many without access to psychosocial care.39 Similarly, Bangladesh depends on over 100 000 community health workers for basic health care, especially in rural areas. Despite notable improvements in maternal and child health, Bangladesh struggles with limited infrastructure and personnel, with only 5.26 physicians per 10 000 people, affecting access to specialized care and cancer treatment.41 Studies have shown the limited infrastructure to enable hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, which can be used in hematologic cancers.42 Similarly, Nepal faces severe shortages in health care professionals and facilities, with only 0.67 hospital beds per 1000 people.43

Limitations of the study include the representativeness of IARC’s GLOBOCAN estimates.44 Notably, only Sri Lanka and India had available subnational data on the incidence of cancer. Building up population-based cancer registry infrastructure through cross-country collaborations in the region (via IARC’s Global Initiative for Cancer Registry Development) could provide more accurate estimates and drive improvements in cancer detection, treatment, and outcomes. For Sri Lanka, the incidence rates obtained from the Colombo district from 2013 to 2017 were applied for the 2022 population, whereas for India, the weighted incidence from numerous districts over 2010 and 2016 were applied to the 2022 population. Given that there was no data available in the other countries for incidence, the mean rates from other countries were used to obtain the GLOBOCAN incidence estimates in 2022. Another limitation is the use of aggregate data that may hide critical contrasts between countries or subpopulations within the SAARC region. For instance, our study does not account for variations in the quality between urban and rural areas or control for socioeconomic differences, leading to only a partial understanding of the entire cancer burden. Similarly, the data itself may be underdeveloped and incomplete, such as with the underreporting of cancer cases and mortality, especially in rural or underserved areas.

A key limitation of the future projections is the assumption of constant age-specific rates through 2045. This modeling approach, although useful for estimating burden under status quo conditions, does not account for possible changes in cancer risk factors, screening uptake, treatment advances, or survival improvements. Therefore, these estimates should be interpreted as baseline forecasts rather than predictive outcomes. Finally, without assessing more longitudinal data, our conclusions are necessarily limited in their scope, as it is difficult to predict a trend over time in the effectiveness of recent public health interventions.

In conclusion, the burden of hematologic cancers in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka is incredibly heterogeneous. This burden should be interpreted in the context of the region's strengths and challenges in providing cancer care. These estimates may guide cancer planning and cancer control strategies, especially in light of the complexities of diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care for patients with hematologic cancers.

Acknowledgments

E.C.D. is funded, in part, through the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award. E.C.D. and P.I. are funded, in part, through the Cancer Center Support grant from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant P30 CA008748).

Authorship

Contribution: A.H., S.R., and U.J. collected the data and conducted the primary analysis; A.H., S.R., and M.S. wrote the initial draft; J.F.W., E.C.D., and F.B. contributed to the methodology; and all authors provided critical review and editing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Edward Christopher Dee, Department of Radiation Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; email: deee1@mskcc.org.

References

Author notes

The data are available from the GLOBOCAN online resource.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.