Visual Abstract

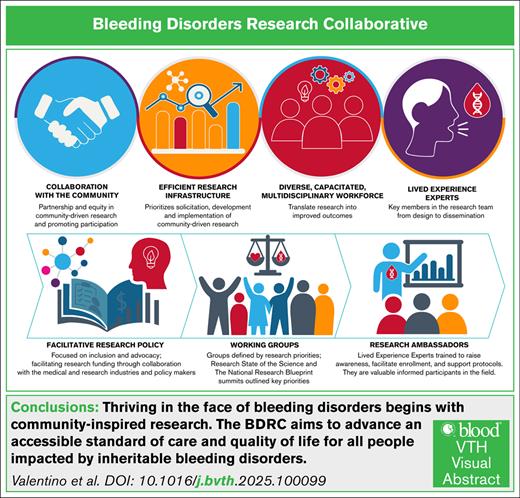

The Bleeding Disorders Research Collaborative (BDRC) aims to advance an accessible standard of care and quality of life for all people living with inheritable bleeding disorders. This goal will be achieved through collaborative and meaningful scientific inquiry, coordinated by an efficient research infrastructure, and undertaken by a diverse, capacitated workforce in partnership with an engaged community. The BDRC is supported by facilitative research policy and grounded in the principles of health equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility, and belonging, striving for dignity, safety, well-being, and opportunities, leading to health justice. Importantly, the initiative is fully informed by lived experience experts, people affected by inheritable bleeding disorders, who are key members in the research development, implementation, and dissemination team.

The voice of the affected individual is central to patient-centered care, a health delivery model focused on empowering the recipients of care by emphasizing what is important to them.1 This model of care improves collaboration and fosters a shared decision-making approach to health care choices, improving outcomes and reducing health care expenditures.2,3 The perspectives of affected individuals and their families, caregivers, and support systems, referred to as lived experience experts (LEEs),4 should inform research and care.1,4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes that LEEs provide unique, valuable insights that help regulators and drug developers better understand the real-life impact of a condition. The FDA established the Patient-Focused Drug Development initiative in 2012.5 This initiative provided deeper insights into the treatment characteristics and outcomes mattering most to individuals with a condition. It has also clarified patient perspectives on meaningful benefits, acceptable toxicity profiles, and preferred methods of engagement in the drug development process.6

Clinical researchers have traditionally not incorporated LEE perspectives into the conceptualization, design, execution, or dissemination of their work; instead, research has primarily been defined by individual investigators and industry priorities. Such narrowly focused research has fallen short, possibly with the exception of male patients with hemophilia, to deliver the full promise and benefit to people with inheritable bleeding disorders (PWIBD), with gaps in diagnosis, treatment, and care persisting. When research is focused on enhancing the health and well-being of a population, the LEE voice should be considered critical to such endeavors. These individuals have unique and unparalleled insights into their conditions and are ideally suited to guide the development of feasible, impactful, and ethically sound research questions. By collaborating with researchers, LEEs can contribute to the implementation, execution, and dissemination of findings. Their lived experience provides expertise not available from other sources, and therefore, LEEs should be viewed as integral members of the research enterprise and not just “human subjects” in studies.

The National Bleeding Disorders Foundation (NBDF), the leading US nonprofit advocacy organization for PWIBD, aims to establish a new research model in which LEEs are equal leaders and partners throughout the research process. The NBDF Bleeding Disorders Research Collaborative (BDRC), an evolution of the National Research Blueprint (NRB), seeks to set research priorities and build the necessary infrastructure to improve the health of PWIBD by centering LEE perspectives and grounding efforts in social justice (Figure 1).

Core areas targeted by the BDRC to create a transformational, community-engaged research enterprise. These core areas include re-envisioning the approach to research, creating a novel process to prioritizing and conducting research, and focusing on outcomes that are meaningful to people who live with BDs. This included prioritizing meaningful research topics, streamlining and democratizing research processes, and ensuring outcomes are relevant, representative, and broadly shared.

Core areas targeted by the BDRC to create a transformational, community-engaged research enterprise. These core areas include re-envisioning the approach to research, creating a novel process to prioritizing and conducting research, and focusing on outcomes that are meaningful to people who live with BDs. This included prioritizing meaningful research topics, streamlining and democratizing research processes, and ensuring outcomes are relevant, representative, and broadly shared.

By setting and addressing these priorities through community-led collaborative research, the BDRC aims to achieve equity for PWIBD, defined by the World Health Organization as the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among people or groups.7 This article will outline the process to date, highlighting collaborative efforts, results thus far, identified challenges and limitations, and comprehensive strategies to ensure success.

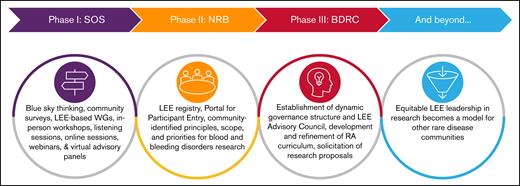

The methodology used at the inception of the BDRC and through each phase of its design, development, and implementation was rooted in constructive and substantial community engagement (Figure 2). In 2020, the Blue Sky Initiative convened LEEs, health care providers (HCPs), regulatory authorities, and representatives from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, FDA, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, industry partners, and community leaders for virtual roundtables to identify shared priorities for the bleeding disorder (BD) community through 2030. A community survey, which consisted of a series of 5-point Likert scale and optional open-ended questions, generated and prioritized a series of action items. This survey was distributed electronically to refine the insights from the roundtables and was available in English and Spanish. Next, the NBDF began phase 1 of the project by forming a steering committee and created 6 interdisciplinary working groups (WGs), which included LEEs, charged with developing the principles, scope, and priorities in broad disease/topic areas for a research agenda (Table 2). These groups engaged in extensive conversations and deliberations focused on priority areas for research over the course of 1 year. The second phase was building an NRB for community-identified research to address key priorities limiting the health and well-being of PWIBD. Finally, phase 3 was establishing the BDRC.

Evolution of the BDRC initiative. The 4 stages of the BDRC initiative are shown schematically: initial visioning and community engagement, identification of research priorities, infrastructure and governance development, and future goals for cross-condition leadership in research. The model anticipates long-term impact through broader adoption of LEE leadership in rare disease research. The first phase of the project, implementation, began with “blue sky thinking,” bringing together healthcare professionals, community leaders, industry and federal partners, and, most importantly, LEEs. In the second phase, a steering committee worked with interdisciplinary WGs to define the principles, scope, and research priorities addressing the community’s most pressing needs. As part of the process, they identified resource and infrastructure requirements to launch and scale an integrated research pathway with opportunities for community participation at every step. A blueprint emerged, designed around the principle that LEEs serve as essential partners in research closely integrating health justice including equity, diversity, inclusion, acceptance and belonging.

Evolution of the BDRC initiative. The 4 stages of the BDRC initiative are shown schematically: initial visioning and community engagement, identification of research priorities, infrastructure and governance development, and future goals for cross-condition leadership in research. The model anticipates long-term impact through broader adoption of LEE leadership in rare disease research. The first phase of the project, implementation, began with “blue sky thinking,” bringing together healthcare professionals, community leaders, industry and federal partners, and, most importantly, LEEs. In the second phase, a steering committee worked with interdisciplinary WGs to define the principles, scope, and research priorities addressing the community’s most pressing needs. As part of the process, they identified resource and infrastructure requirements to launch and scale an integrated research pathway with opportunities for community participation at every step. A blueprint emerged, designed around the principle that LEEs serve as essential partners in research closely integrating health justice including equity, diversity, inclusion, acceptance and belonging.

Among the prioritized themes to emerge from the Blue Sky initiative were sustainability of the integrated comprehensive care model,8 access to and improvements upon mental health resources, leveraging technology (eg, telehealth services) to achieve the greater goal of expanding access to care, and the expansion of newborn screening programs for BDs, and the top priority was research designed to address the needs of BD community including underserved populations such as women, girls, people with the propensity to menstruate, and those with rare BDs (Table 1).

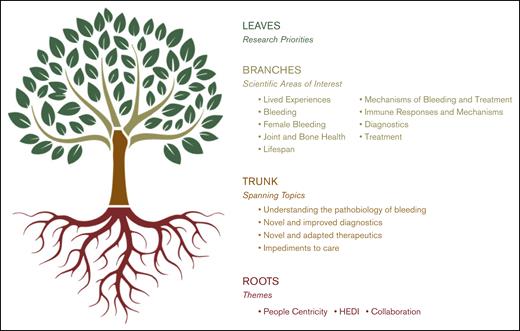

The Research State of the Science (SOS) culminated with a summit9 and the publication of a series of manuscripts describing the research priorities in each of the 6 areas (Table 2).10-15 Three global themes emerged as central to the creation of a functional research environment: people centricity, collaboration, and health equity, diversity, and inclusion (HEDI; Figure 3).

Visualization of the BDRC priority-setting model. Rooted in the foundational themes of people centricity, HEDI, and collaboration, this tree structure maps the development from spanning research topics and scientific areas of interest established through the SOS to a rich canopy of community-driven research priorities established through the NRB phase. Main branches reflect broad spanning topics, whereas smaller branches denote scientific areas of interest. The leaves symbolize specific research priorities developed and refined through NRB WGs. A leaf may be taken from the tree to create a specific research project.

Visualization of the BDRC priority-setting model. Rooted in the foundational themes of people centricity, HEDI, and collaboration, this tree structure maps the development from spanning research topics and scientific areas of interest established through the SOS to a rich canopy of community-driven research priorities established through the NRB phase. Main branches reflect broad spanning topics, whereas smaller branches denote scientific areas of interest. The leaves symbolize specific research priorities developed and refined through NRB WGs. A leaf may be taken from the tree to create a specific research project.

Overlapping priorities common to multiple disorders became evident. For example, joint disease due to bleeding was a common feature across sex and gender for people living with hemophilia A or B but also for those with type 3 von Willebrand disease and several other ultrarare BDs. Similarly, biomarkers of bleeding and subclinical bleeding were identified as necessary to improve the care of people with hemophilia as well as those with platelet disorders or rare factor deficiencies. A keener understanding of the role blood vessels play in bleeding and wound healing is important for all people with BDs, irrespective of the specific diagnosis.

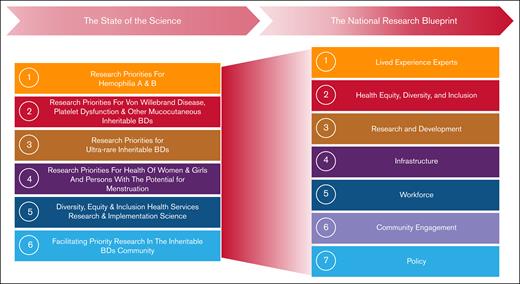

The SOS produced a list of prioritized LEE-centric research questions in specific focus areas (Figure 4, left).10-15 In the NRB, new interdisciplinary WGs that included LEEs were established to develop a blueprint outlining the infrastructure and strategies needed to address them across 7 key areas (Figure 4). Each WG developed initial focused recommendations for NRB implementation, then collaborated across groups to refine and harmonize a draft for community input. A survey featuring 40 multiple choice and optional open-ended questions was launched, in both in English and Spanish. The survey, which described the proposed blueprint through text and illustrations, received 154 responses (87 complete and 67 partial). Of the respondents, 47% had previously participated in the NRB; 32% were LEEs, 24.8% allied professionals, 22.2% physicians and researchers, 13.7% government and nonprofit partners, and 7.2% industry partners. Each WG presented its suggestions at the 2024 in-person summit, marking the BDRC’s next phase: implementations. These recommendations are currently being prepared for publication.

The evolution of the WGs from the SOS to the NRB. This figure illustrates the transition of key research priorities identified during the SOS process into the strategic pillars of the NRB. The left side of the figure outlines the 6 WGs established during the SOS. The right side depicts the 7 WGs of the NRB that generated the overarching research themes, which together demonstrate how the initial research priorities have informed and broadened into a comprehensive national agenda for BD research.

The evolution of the WGs from the SOS to the NRB. This figure illustrates the transition of key research priorities identified during the SOS process into the strategic pillars of the NRB. The left side of the figure outlines the 6 WGs established during the SOS. The right side depicts the 7 WGs of the NRB that generated the overarching research themes, which together demonstrate how the initial research priorities have informed and broadened into a comprehensive national agenda for BD research.

To create a functional research infrastructure, each WG recommended processes for facilitating the solicitation, development, and implementation of community-prioritized research, recruiting, training, and embedding LEEs, HEDI champions, and other community members throughout and supporting BD research and workforce development.

Existing systems, processes, and organizations, such as the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network, Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society, the Clinical Research Training Institute of the American Society of Hematology, and others, who support robust clinical research, data collection, mentoring, and workforce development offer substantive potential collaborative partnerships essential to furthering the goals of the BDRC.

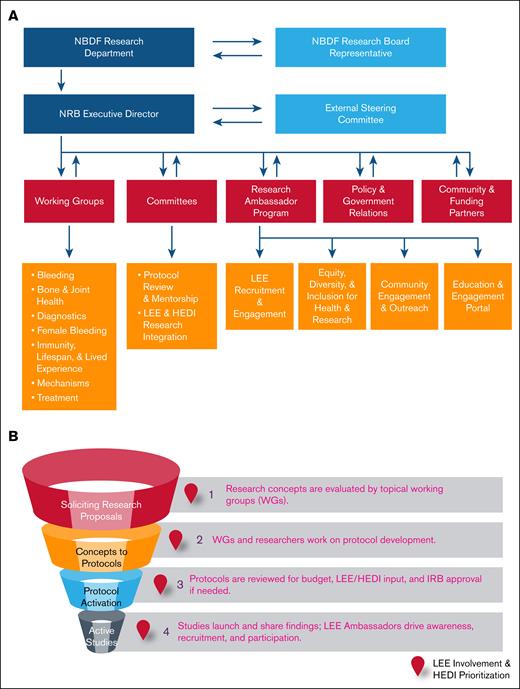

Key to the BDRC is an agile infrastructure capable of meeting the community's needs. An 8-member group developed guiding principles, a dynamic governance model, a project map, and a framework for member engagement (Figure 5A). They proposed infrastructure with minimal requirements (minimal viable product) for evaluating and launching community-driven research (Figure 5B), designed to iteratively build upon itself and expand as funding and research needs grow.

Research governance and study activation workflow. (A) The dynamic organizational framework of the BDRC with a hierarchical governing structure that includes key stakeholders provides oversight of research activities. (B) Project map outlining the stages from research proposal solicitation to active studies, highlighting critical review and approval points, including LEE/HEDI considerations. IRB, institutional review board.

Research governance and study activation workflow. (A) The dynamic organizational framework of the BDRC with a hierarchical governing structure that includes key stakeholders provides oversight of research activities. (B) Project map outlining the stages from research proposal solicitation to active studies, highlighting critical review and approval points, including LEE/HEDI considerations. IRB, institutional review board.

Strong collaboration with the other WGs fostered a dynamic, evolving framework that supports early participation and allows for continuous learning and expansion. The infrastructure WG emphasized the need for projects to unite diverse stakeholders and support iterative research to improve LEE lives. The project process map includes links to facilitate training, education, participation, and collaboration, while also promoting engagement, resource access, capacity building, mentoring, and partnerships.

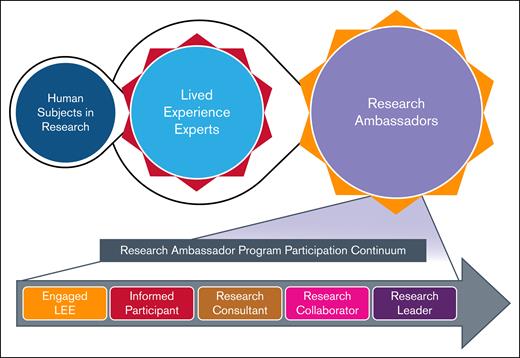

A WG consisting of 16 members presented a pathway within the blueprint for achieving the full spectrum of LEE participation in the global research process. LEE participation can range from participants in research to serving as consultants to researchers, as members of the research team with all the rights and responsibilities of other team members, as a coinvestigator leading aspects of the research, and ultimately, as a researcher leading the research project and team. LEEs may be involved in research design, review, implementation, data collection and monitoring, and peer-to-peer dissemination of research results. To accomplish this, the proposed infrastructure incorporates LEEs in every phase of the work (Figures 5 and 6).

The evolution of LEE involvement in the BDRC and the RA program participation continuum. This figure illustrates the progression of individuals from being human subjects in research to engagement as LEEs, for their expertise in living with a BD, and subsequently participating as RAs. The top portion depicts this evolution, highlighting the transition and central role of LEEs. The bottom portion presents the RA program participation continuum, showcasing the increasing levels of engagement and leadership roles that trained LEEs can assume, ranging from engaged LEE and informed participant to research consultant, research collaborator, and ultimately research leader. Broad viewpoints and perspective will be welcomed among the LEEs that participate in the BDRC. Those selected for the RA Program will need to be highly motivated and have ample time to commit to the project.

The evolution of LEE involvement in the BDRC and the RA program participation continuum. This figure illustrates the progression of individuals from being human subjects in research to engagement as LEEs, for their expertise in living with a BD, and subsequently participating as RAs. The top portion depicts this evolution, highlighting the transition and central role of LEEs. The bottom portion presents the RA program participation continuum, showcasing the increasing levels of engagement and leadership roles that trained LEEs can assume, ranging from engaged LEE and informed participant to research consultant, research collaborator, and ultimately research leader. Broad viewpoints and perspective will be welcomed among the LEEs that participate in the BDRC. Those selected for the RA Program will need to be highly motivated and have ample time to commit to the project.

LEEs possess a unique, diverse, and invaluable perspective on all conditions affecting their lives. Therefore, LEE participation is critical to the success of this endeavor and is the core of the entire project. Inherent in this is the notion that research partnership is formulated based on research being created, planned, and executed for, with, and by LEEs beyond their inclusion as research subjects, with the goal of improving health care outcomes and quality of life for PWIBD.

Recognizing the value of LEEs beyond participation16 is vital to the success of the BDRC. Therefore, LEEs will have the opportunity to become research ambassadors (RAs), knowledgeable, empowered members of the research team who will help raise awareness about opportunities, facilitate enrollment, and support protocol adherence (Figure 6).16 Formal RA training, education, and ongoing mentorship in research principles and practices will equip LEEs with research fundamentals, enabling them to engage as equal partners on the research team. Similarly, BDRC researchers will receive complementary training to work optimally with LEEs and RAs and fully capture the value they bring.

As a first step, LEEs can be involved in the codevelopment of research questions addressing their current unmet needs.17 LEEs can also have important insights into the outcomes mattering most to them and what measures may best assess those outcomes. This takes little additional training or education and emphasizes their valuable insights gained from lived experiences. Moving beyond this step and meeting the obligations of an investigator will require substantial training and education. In accordance with federal guidelines, members of the research team must have the education, training, and experience qualifying them as an expert in clinical investigation according to the US Code of Federal Regulation 21 US Code of Federal Regulation 312.60; agree to conduct the research in accordance with the relevant, current protocol; and protect the safety, rights, or welfare of participants in the research. The infrastructure of the BDRC seeks to provide opportunities for interested LEEs to acquire the necessary knowledge to become RAs and, as such, members of the research team. Once they acquire knowledge of the complexities of research, including the procedures and activities involved in conducting and monitoring a research study, RAs can also make substantive contributions to the recruitment plan, ensuring diverse populations are represented. They will provide valuable input into the study consent form and study materials.

As they acquire skills and knowledge, the RAs interested in deeper engagement may participate in protocol review as members of the research team or an institutional review board. RAs can also assist in data collection and oversight, including participation in data safety monitoring boards and observational study monitoring boards. Finally, the dissemination of research findings is critical and provides a clear opportunity for RAs to codevelop and share findings with the community through data review, manuscripts, lay summaries, dissemination materials, and presentations at educational events and scientific conferences.

Community engagement has demonstrated benefits as an approach for health promotion, disease prevention, and health care delivery but has also been shown to enhance research.18 A recent example of the success of community engagement facilitating research is the Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19. Central to the BDRC infrastructure is community engagement, to identify and recruit a diverse LEEs, researchers, and others to participate. The first step in engaging with the BD community is defining it. Over the past 4 years, many community members have contributed their voices to the Blue Sky Initiative, the SOS, and the NRB, including LEEs, chapter representatives, industry and commercial partners, researchers, multidisciplinary clinicians, government agencies, and patient advocacy organizations. NBDF has 52 local chapters spread across the United States in 45 states to serve the needs of people living with inheritable blood and bleeding disorders providing advocacy and education. This robust representation has provided key insights and diverse input.

A WG consisting of 4 members presented a plan and pathway for realizing the full spectrum of community participation in the global research process. Ongoing bidirectional communication will be essential (Figure 5A). A user-friendly central hub or web-based portal is necessary to facilitate connections between community members and allow engagement and training. NBDF’s Community Voices in Research portal, a community-powered registry supported by NBDF, gathers information through electronic surveys to help researchers understand the experience of living with BDs directly from LEEs.19 Community Voices in Research portal has the capability to serve as this central hub for community information, engagement, and participation and will therefore be leveraged by the BDRC.

This WG introduced the concept of the BDRC as a “community table,” at which community members not only share a meal but together take part in making the food being consumed and enjoyed by all. The group stressed that in the BDRC model, this metaphorical table belongs to the LEEs, and the rest of the community gathers at their invitation. To ensure equitable access to this shared meal, the community web-based engagement portal is particularly critical for LEE recruitment and RA training. Although some LEEs are already experts in the field of biomedical research, such as scientists, physicians, nurses, and other HCPs, others unfamiliar with the research process will require training and education to understand its policies and practices.

LEEs interested in contributing to research will take a survey to gauge their current level of skill and understanding. The portal will then generate an individualized educational road map including modules and tool kits designed to meet their specific needs. Creating flexibility to meet people wherever they are in the continuum of research literacy is important, as is the ability to track and report progress for all levels of learners. The portal will additionally facilitate connections and networking opportunities with others interested in similar areas of research. In this way, effective partnerships can be created to answer key questions.

Promoting BDRC participation will be challenging, including overcoming habits, physical constraints, and geographic, institutional, and time barriers to collaboration. Demonstrating value and impact will be key in addressing each of these challenges.

The BDRC infrastructure is grounded in inclusive, representative policies and advocates for the BD research community, especially on research funding issues. The policy WG consisting of 8 members, identified 5 critical policy-related stakeholders: (1) LEEs with firsthand knowledge and insights into their lived experiences; (2) advocacy groups such as NBDF who have the ability to influence public opinion and policy makers; (3) federal and state policy makers; (4) government agencies, including the FDA, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Services Resource Administration, and Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health; and programs such as Department of Defense Congressional Directed Medical Research Programs, and Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute; and (5) finally, HCPs and researchers involved in direct patient care alongside pharmaceutical and industry partners who seek to address the community’s health care needs through medicinal products and devices.

Financial resources to support current and new initiatives, such as the BDRC, have been traditionally limited among these stakeholders. Identifying and addressing challenges in securing adequate funding, as well as developing strategies to overcome these impediments, will be vital to its success. Policies that facilitate research funding and prioritize BDRC focus areas, all while encouraging collaboration among LEEs, researchers, and HCPs, would accelerate research progress and achieve its goals. Appropriations strategies (funding/report language) to support funding for specific BDRC project areas would enhance the likelihood of success and improve the health and well-being of PWIBD. The US Office of Pharmacy Affairs within Health Services Resource Administration provides guidelines as to how monies generated by hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) under their 340B drug pricing program, designated as program income, can be spent.20 By law, program income must be used for patient health, education, and supportive services necessary in the provision of comprehensive care. This includes support for nurses, social workers, and physical therapists, who are considered to provide nonreimbursable services.21 The use of program income for research has been granted on a limited case-by-case basis at the regional level; however, policy changes to facilitate HTCs using program income to support BDRC research would ensure the success of this enterprise.

Leading up to the 2024 summit, it was clear that HEDI and belonging were top of mind for all stakeholders. Recognizing this, it was necessary to develop an infrastructure prioritizing these principles. The HEDI WG aimed to define how these factors affect research and clinical trials involving PWIBD and to ensure their systematic consideration, monitoring, and evaluation within the BDRC. The 10-member WG codeveloped guiding principles and identified conscious and unconscious biases as key barriers to collaborative research within the health care system, including HTCs. Addressing these biases is a critical priority of the BDRC, which seeks to develop policies and practices that enable meaningful engagement with LEEs, especially from marginalized and minoritized populations. Removing barriers to their participation in research is essential to fostering a fair, just, and representative research enterprise. Equally important is ensuring that training for both the LEEs and workforce incorporates principles of equity and justice.

Advancing evidence-based care for all PWIBD requires inclusive research participation; yet access to research opportunities and clinical advances remains inequitable. Social drivers of health, systematic differences in health for different groups of people that are avoidable by reasonable action,22 likely play a significant role in these disparities. A recent review of the BD literature identified rural locations as a significant contributor to both delayed diagnosis and decreased access to care.23 A 2020 survey of 70 Canadian HCPs for PWIBD identified and highlighted significant diagnostic delays for people with mild symptoms, women with abnormal uterine bleeding, and those in rural areas.24 Therefore, disparities exist based on socioeconomic, geographic, language, and other barriers, impeding access to care.

Conscious and unconscious biases within the US health care system affect patient-clinician communication, clinical decision-making, and institutional practices.25 Within the HTC network, race and ethnicity influence health care access and quality, particularly in areas such as inhibitor management and services for women, girls, and people with the propensity to menstruate.26 Mitigating these biases through training and education is necessary to achieve more equitable outcomes. Health equity means everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. Achieving this requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination and their consequences (including powerlessness), lack of access to fair-paying jobs, quality education, housing, health care, and safe environments.27

HEDI must lead the way toward health justice. This requires transformational change, building power by cultivating the political capacity of people who are disproportionately harmed by health inequity and, at the same time, destabilizing and deconstructing the economic and political forces perpetuating health inequity.28,29 To ensure all PWIBD can participate in research, barriers facing marginalized and minoritized populations must be addressed. The BDRC offers an opportunity for everyone to participate in research at the level they choose.

A functional research enterprise requires a capacitated and self-renewing workforce to translate gaps in clinical outcomes to research questions. The proposed infrastructure (Figure 5) incorporates LEEs and HEDI principles to address the gaps in care that preclude PWIBD from achieving health equity and eliminating avoidable and remediable differences in their outcomes.

An 8-member multidisciplinary WG provided workforce recommendations for the BDRC. The core recommendation was that HTCs continue to support evidence-based care for PWIBD and that evidence-based care is founded upon research. Fostering an HTC culture including advancing care through a national research agenda will enhance outcomes for the community, and the multidisciplinary team is critical to achieving this objective. Research should be a priority, with job descriptions and core functions of the team members reflecting their roles in the process and program income being used to support these duties. Promoting participation in existing and/or newly developed research and educational programs for all disciplines will be required.

A survey conducted by this WG revealed >93% of HTC multidisciplinary staff expressed interest in meaningful research participation, yet most dedicate <10% of their time to it. Among the barriers to participating in clinical research, lack of time, lack of staffing, and lack of job structure for research were the most cited. Therefore, more education and training will be required to achieve proficiency. In addition, protected time and budget allocations devoted to research for all members within the multidisciplinary team will be necessary. Vital to the expansion of research capabilities within HTCs is collaboration with others, such as Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society and Partners in BD Education, professional organizations dedicated to medical education and mentorship for physicians, investigators, and all HCPs interested in advancing care for PWIBD.

Once an infrastructure is in place and the workforce is enabled to participate in and conduct research, the voice of LEEs can guide the research enterprise toward the most impactful results. Expert WGs, including LEEs and HEDI champions, evaluate research concepts. Impactful concepts progress to collaborative protocol development and refinement, including budgeting, before studies are activated and supported by RAs (Figure 5B).

At this point, decisions on what research should be prioritized can be made. Prioritizing research questions must also be considered in terms of feasibility of execution and time to success (eg, 1-2 years, <5 years, and >5 years to complete), impact of the outcomes being studied on PWIBD’s health and health care access, and acceptability in terms of benefits, risks, and costs to participants.9 A clear lens of equity and justice must be used to assess each project to determine the most impactful and feasible scientific priorities.

The research and development WG, consisting of 12 members, refined the community-developed SOS priorities and grouped them into 9 broad topics (Figure 3). These spanning topics encompassed the full spectrum of inherited BDs and were further broken down into scientific areas of interest and then into specific research priorities (for a complete list of these research priorities, please see NRB-Brochure-Research-Priorities.pdf). For example, in the broad topic of lived experiences, there were 6 scientific areas of interest and 57 research priorities, whereas in female bleeding, there were 4 scientific areas of interest and 35 research priorities. Gaps in basic and translational priorities were also addressed in this schema.

Importantly, this research agenda would inform the research development processes within the supportive infrastructure. The re-envisioned research agenda serves as a road map to guide community members and multidisciplinary investigators in designing impactful, cross-disciplinary, and iterative research that advances knowledge and improves the lives of all PWIBD.

The SOS, the NRB, and the Capstone summit solidified our vision: thriving in the face of BDs begins with community-inspired research and drives the BDRC mission to advance an accessible standard of care and improve the quality of life for all PWIBD. This will be accomplished through collaborative and meaningful scientific inquiry, coordinated through an efficient research infrastructure, undertaken by a diverse capacitated workforce in partnership with an engaged community, supported by facilitative research policy, grounded in the principles of HEDI, and fully informed by RAs who are key members in the research development and implementation team.

The initial goals of the BDRC are fourfold: (1) delineate its governance and operational structure including the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders; (2) outline actionable strategies to address the most important needs today and identify opportunities to accelerate research to address these needs; (3) have well-defined milestones and timelines; and (4) establish mechanisms for evaluation and improvement. These goals can be accomplished via mutual respect, authentic partnerships, and respectful communications. The achievements of the BDRC to date are described in Table 3 and include examples of paradigm-changing impact.

Limitations of the proposed model include a divergence from the “status quo” of how research has historically been conducted and, more importantly, how researchers have traditionally been trained and behaved. A paradigm shift is needed to successfully implement this model of codevelopment of the research question, cocreation of research protocols, and coexecution and codissemination of findings. Education of all parties, including researchers and LEEs, will be necessary to achieve this shift. This process has already begun by initiating collaborations with important partners to inculcate this model. Another limitation is funding for a novel approach to research. Again, this will require advocacy and education of funding agencies and partners as to the value of this new model to bring benefit to the health care ecosystem including PWIBD. Finally, maintaining inclusive representation on the part of LEEs and researchers will require steadfast attention to community trends and voices.

The research ecosystem termed the BDRC begins with community-developed and -prioritized research (Figure 3), followed by solicitation of LEE-centered research proposals and concepts to be evaluated by topical WGs, for their impact, feasibility, and risk (Figure 5B). These WGs, which include LEEs, will then collaborate with research teams in protocol and budget development and refinement, created with LEEs and HEDI in mind. Once studies are activated, LEEs will serve as ambassadors to support awareness, recruitment, and participation (Figure 6). When the research is completed, the LEEs will support publication and dissemination of results. In some cases, LEEs will ascend to be members of the research team and may even lead their own research.

The BDRC aims to accelerate progress in addressing unmet medical needs and improving health outcomes and quality of life for PWIBD. By leveraging integrated data collection and advanced tools, such as artificial intelligence, natural language processing, and machine learning, it will generate novel insights and support iterative research. This approach will streamline the path from discovery to delivery, optimize resources, and ensure all efforts are guided by LEEs, redefining the treatment of BDs.

Acknowledgments

More than 125 community members including lived experience experts, the National Bleeding Disorders Foundation (NBDF) chapter representatives, health care providers, and industry and federal partners, along with many others, contributed to various aspects of this work to build the Bleeding Disorders Research Collaborative (BDRC). The authors owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to all the working group leaders and members of those groups for their tireless efforts to create a unique research enterprise for people with inheritable bleeding disorders. The authors thank Brianna Moy for preparing the visual abstract.

This project has been funded by the NBDF, and no external funding was received for the development of this manuscript or the BDRC.

The manuscript was developed in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Authorship

Contribution: M.E.S., M.R., D.D., and L.A.V. conceived of the manuscript; L.A.V. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; M.E.S., M.R., H.B., D.D., R.S., S.V., and L.A.V. edited multiple draft versions of the manuscript, and discussed and reconciled the differences; and all authors contributed to the topic development, edited the final version of the manuscript, and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.A.V. reports honoraria and travel support from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc for speaking; and consulting fees from Inovio, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Sanofi, and Takeda. M.E.S., M.R., and H.B. are employees of National Bleeding Disorders Foundation (NBDF). M.L.W. was an employee of NBDF at the time this work was performed. D.D. is a paid consultant to NBDF, the American Society of Hematology, and Believe Limited LLC. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Leonard A. Valentino, Rush University Medical Center, 1725 W Harrison St, Chicago, IL 60612; email: whybloodclots@gmail.com.