Direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOACs) are indicated to prevent vascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) without concomitant valvular disease or severe chronic kidney disease (CKD), groups in which warfarin is the preferred choice. We aimed to evaluate the safety of DOACs in these populations compared to warfarin. We conducted a systematic review in MEDLINE, Embase, and Evidence Based Medicine Reviews to identify randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs assessing warfarin or DOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, or edoxaban) in patients with AF with concomitant valvular disease or CKD (according to Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines) that reported on bleeding, stroke, or systemic/arterial thromboembolism. Meta-analysis was performed for eligible studies using the Mantel-Haenszel method random effects model. Of 3172 screened studies, we included 110 studies (310 478 patients with concomitant AF and CKD; 99 299 patients with concomitant AF and valve disease). Meta-analysis showed that, compared to warfarin, in patients with concomitant AF and CKD, DOACs were associated with reduced bleeding (odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [Cl], 0.49-0.88; P = .005) and strokes (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.85; P = .004), particularly in patients with stages 4 and 5 CKD and dialysis patients. In patients with concomitant AF and valvular disease, DOACs were associated with reduced bleeding (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.97; P = .03) and stroke incidence (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.47-0.93; P = .02). Differences were noted for RCTs and non-RCTs. Our findings suggest that DOACs may be equivalent or superior to warfarin both in the prevention of thromboembolic events and reduction of bleeding in these patients.

Introduction

In recent years, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, or dabigatran have become the first-line choice for most anticoagulant indications, because they have been shown to be equivalent or superior to warfarin in the treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) in several large-scale trials, have fewer food and drug interactions, and have no need for coagulation test monitoring.1-3 Such trials have solidified the role of DOACs in AF treatment and informed many current guidelines.1-4

The RE-LY trial enrolled 18 113 participants and compared dabigatran with warfarin. It showed dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for the primary efficacy outcomes of stroke and systemic embolism and was superior to warfarin for the primary safety outcome of bleeding depending on the dosage. The ROCKET-AF trial enrolled 14 264 participants and compared rivaroxaban to warfarin, demonstrating that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism and led to fewer occurrences of intracranial and fatal bleeding. ARISTOTLE included 18 201 participants and found that apixaban was superior to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism, caused less bleeding, and resulted in lower mortality. Lastly, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 enrolled 21 105 participants and showed that edoxaban was noninferior to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism and was associated with significantly lower rates of bleeding and death from cardiovascular causes.

All these large-scale regulatory studies excluded patients with concomitant moderate to severe mitral stenosis, patients with bioprosthetic heart valves, and patients with severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <25-30 mL). As a result, although DOACs have been established for use in nonvalvular AF in patients without comorbidities, it is less clear how efficient and safe they are in these populations. Currently, for patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD) or on dialysis, guidelines from both American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology do not routinely recommend DOACs.5,6 Similarly, both American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines currently recommend warfarin over DOACs in some patients with valvular AF, such as moderate and severe mitral stenosis.5,6 This study aimed to review the outcomes of available literature to analyze the safety and efficacy of DOACs compared to warfarin in patients with concomitant AF and valvular disease or concomitant AF and CKD. To further characterize the comparative benefits and risks of DOACs, our review included subgroup analyses of specific DOACs as well as patients with different stages of CKD.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines. The review is registered on the International Prospective Registry of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; ID CRD42022322633).7

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included adult patients (aged >18 years) with concomitant AF and valvular disease (stenosis or regurgitation of the mitral, tricuspid, pulmonary, or aortic valve) or those with concomitant AF and CKD who are treated with warfarin or one of the following DOACs: rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, or edoxaban. Eligible studies assessed at least one of the following primary outcomes: bleeding, stroke, or systemic/arterial thromboembolism. If available, all-cause mortality was included. In addition, study design was limited to randomized-controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, or case-control studies from peer-reviewed journals. Conference proceedings and case studies were excluded. Patients with mechanical valves were excluded. Studies were also limited to those in English to mitigate the risk of mistranslation.

Information sources

Potentially relevant studies were identified through literature searches conducted in databases including MEDLINE, Embase, and Evidence Based Medicine Reviews–Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (all via Ovid interface). Key words and medical subject headings were used to identify all relevant studies from inception until 2022. Manual citation screening of included trials was also conducted to ensure a comprehensive search. The complete search strategy is available in the supplemental Materials under “Complete search strategies.”

Study selection and screening

All literature search results were uploaded to Covidence (Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; available at www.covidence.org) and duplicates were removed through automated and manual duplicate checks.

Two reviewers (A.L. and C.W.) independently conducted a title abstract screening of the eligible articles. Potentially relevant studies underwent full-text screening by both reviewers independently. After each level of screening, conflicts were resolved during a consensus meeting between reviewers. Cohen κ coefficient was used to assess interrater reliability.

Data items

Data were extracted independently by 2 reviewers using a standard form. Discrepancies were resolved during a consensus meeting. Extracted data pertained to study characteristics (authors, publication date, study design, location, and number of participants), participant demographics (age, sex, concurrent antiplatelet use, comorbid conditions including heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, previous stroke, and previous venous thromboembolism), CKD stage, intervention (medication and dosage), and outcomes measured (major bleeding, gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, intracranial bleeding, overall strokes, transient ischemic attack [TIA], systemic/arterial thromboembolism, and all-cause mortality). Bleeding events were defined individually by each trial and summarized in supplemental Materials. In most cases, the definition from International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) was used.8 For patients with CKD, stages were defined by individual studies, but most used estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) based on the criteria from National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines: stage 1 eGFR >90 mL/min per 1.73 m2; stage 2 eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min per 1.73 m2, stage 3 eGFR 30 to 59 mL/min per 1.73 m2, stage 4 eGFR 15 to 29 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and stage 5 eGFR <15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.9

Risk-of-bias assessment

For randomized studies, the second version of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) and the Jadad Scale were used to assess the risk of bias in all the studies analyzed in this article.10,11 For nonrandomized studies, the risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were used to assess the risk of bias.12,13 Complete risk-of-bias information can be found in the supplemental Materials (supplemental Figures 1 and 2; supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Data synthesis methods

Meta-analysis was conducted on eligible studies with available information. Data extracted included the number of patients and incidence of events. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. A random effects model was used as statistical heterogeneity was high (I2 > 50%) based on Higgins I2 statistics. The results of the meta-analysis were reported using forest plots, and publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager (RevMan, version 5; The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

When data allowed, we compared primary and secondary outcomes based on subgroups of (1) RCT vs non-RCTs, (2) specific DOACs, (3) stages of CKD, (4) valve disease with or without replacement/repair, (5) types of bleeding (GI or intracranial), and (6) overall stroke vs TIA.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The PRISMA flow diagram of screening process is included in supplemental Figure 3. The initial search yielded 3172 results. After title and abstract screening, 284 studies underwent full-text screening, and 110 met the inclusion criteria. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in the supplemental Materials (supplemental Tables 3-6). For RCTs examining patients with CKD, the mean age of participants ranged from 64.2 to 81 years, and the percentage of male participants was between 38.2% and 86.3%. For non-RCTs of patients with CKD, the mean age ranged from 59.8 to 84.6 years, and the percentage of male participants ranged from 36.7% to 95.9%. For RCTs assessing patients with valve disease, the mean age ranged from 45.7 to 92 years, and the percent of males ranged from 20.2% to 60.9%. Valve disease included mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, aortic regurgitation, aortic stenosis, and tricuspid regurgitation with or without valve repair and replacements. For non-RCTs examining patients with valve disease, the participants’ mean age ranged from 59.2 to 84 years, and the percentage of male participants ranged from 5% to 66.7%.

A summary of all quantitative results is shown in Tables 1-4. The funnel plots for each one of the main analyses can be found in the supplemental Materials.

Patients with concomitant AF and CKD

Our analysis of patients with concomitant AF and CKD assessed 15 RCTs and 65 non-RCTs, including 310 478 patients, with 55 259 total participants in RCTs and 255 219 participants in non-RCTs. For studies that include both patients with and without CKD, only participants with CKD were included in this study. If eGFR was specified in study, the patients were included in both overall and sensitivity analyses with different eGFR stages. The main analyses of DOACs are limited to apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban. The decision to exclude edoxaban from the main analyses is due to both the limited data pertaining to edoxaban specifically (3 RCTs and 2 non-RCTs) as well as its limited use in clinical settings.

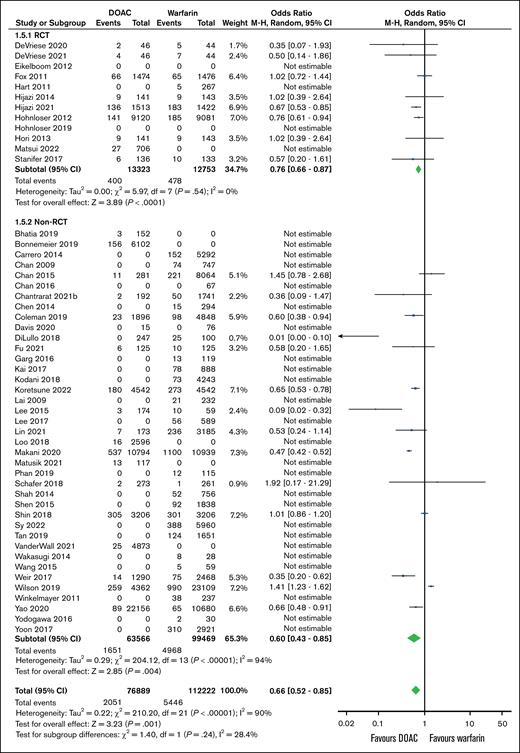

Bleeding events

A total of 12 RCTs and 63 non-RCTs evaluated overall bleeding as an outcome. Meta-analysis of RCTs showed no significant difference in the number of bleeding events between warfarin and DOACs (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59-1.04; P = .09). Meta-analysis of non-RCTs favored DOACs for fewer bleeding events (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88; P = .005; Figure 1).

Association between the number of overall bleeds and anticoagulation choice (DOAC vs warfarin) in patients with concomitant AF and CKD. df, degrees of freedom.

Association between the number of overall bleeds and anticoagulation choice (DOAC vs warfarin) in patients with concomitant AF and CKD. df, degrees of freedom.

Subgroup analyses included studies that reported on specific etiologies of bleeding (GI bleeding or intracranial bleeding). Nineteen non-RCTs (48 705 participants) reported on GI bleeding (supplemental Figure 4). The non-RCTs found that DOACs were associated with a decreased odd of GI bleeding compared to warfarin (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50-0.92; P = .01). Only 1 RCT reported outcomes for GI bleeding events; therefore, no meta-analysis was performed.

There were 3 RCTs and 14 non-RCTs that examined intracranial bleeding (supplemental Figure 5). RCTs (15 203 participants) showed that DOAC use over warfarin use had no statistically significant associations with intracranial bleeding (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.63-1.31; P = .61). In contrast, non-RCTs (33 917 participants) found that DOAC use was associated with decreased intracranial bleeding (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.36-0.76; P < .001).

Stroke incidence

Stroke incidence was assessed in 12 RCTs and 39 non-RCTs including 26 076 and 163 035 participants, respectively. The analyses of both RCTs and non-RCTs found that using DOACs were associated with decreased stroke odds in both RCTs (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.66-0.87; P < .001) and non-RCTs (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.85; P = .004; Figure 2).

Association between incidence of strokes and anticoagulation choice (DOAC vs warfarin) in patients with concomitant AF and CKD. df, degrees of freedom.

Association between incidence of strokes and anticoagulation choice (DOAC vs warfarin) in patients with concomitant AF and CKD. df, degrees of freedom.

Systemic/arterial embolism and all-cause mortality

There were 12 non-RCTs including 47 641 participants that analyzed the incidence of systemic/arterial embolism (supplemental Figure 6). No RCT assessed this outcome. The meta-analysis of non-RCTs did not find a difference in incidence of systemic/arterial embolism between DOACs and warfarin (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.13-1.81; P = .28).

There were 12 RCTs (31 886 total participants) and 30 non-RCTs (121 728 total participants) that assessed all-cause mortality (supplemental Figure 7). The meta-analysis of both RCTs and non-RCTs found that DOACs were associated with decreased odds of all-cause mortality (RCTs [OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.78-0.97; P = .01] and non-RCTs [OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.65-0.84; P < .001]).

Sensitivity analyses for individual DOACs

We conducted a sensitivity analysis for comparisons between warfarin and individual DOACs. In comparisons between warfarin and apixaban, there were 3 RCTs with 20 647 participants and 11 non-RCTs with 48 091 participants that assessed major bleeding (supplemental Figure 8). The results found apixaban to be associated with decreased odds of bleeding in both meta-analyses (RCTs [OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.55-0.75; P < .001] and non-RCTs [OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.44-0.63; P < .001]). Stroke incidence was assessed in 3 RCTs (21 405 participants) and 3 non-RCTs (22 144 participants; supplemental Figure 9). Results favored apixaban in both RCTs (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61-0.83; P < .001) and non-RCTs (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.41-0.87; P = .007).

Regarding comparisons between warfarin and dabigatran, there were 9 non-RCTs that assessed overall bleeding with 42 120 total participants (supplemental Figure 10). There was no significant difference found (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.53-1.02; P = .07). Three non-RCTs with 26 905 total studies compared stroke incidence in warfarin and dabigatran treatments (supplemental Figure 11). There was no significant difference found (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.44-2.13; P = .94).

Finally, for comparisons between warfarin and rivaroxaban (supplemental Figure 12), bleeding events were assessed in 5 RCTs (3940 participants) and 9 non-RCTs (50 725 participants). There was no significant difference in RCTs (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73-1.18; P = .56), but in non-RCT studies, rivaroxaban was favored over warfarin (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.71-0.87; P < .001). Stroke incidence was assessed in 5 RCTs with 4120 participants and 7 non-RCTs with 43 892 participants (supplemental Figure 13). The RCT analysis found no significant difference (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69-1.29; P = .71), whereas the analysis of non-RCTs favored rivaroxaban (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.38-0.83; P = .004).

The comparison of warfarin and edoxaban was limited by the number of studies. The only outcome examined was bleeding events, and there was no significant difference in the odds of number of bleeding events in RCTs (3 studies with 18 419 participants; OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.65-1.44; P = .88) or non-RCTs (2 studies with 6078 participants; OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.39-1.11; P = .12).

Subgroup analysis by CKD stages

There was a total of 30 non-RCTs including 118 141 patients that assessed the number of bleeding events for specific stages of CKD. Of those studies, there were 8 studies with 37 718 participants who had stage 1 or 2 CKD, 11 studies with 43 669 patients who had stage 3 CKD, 10 studies with 5906 patients who had stage 4 or 5 CKD, and 15 studies with 30 848 patients who were on dialysis.

Other than stage 1 or 2 CKD, in all other groups, DOACs resulted in decreased odds of bleeding over warfarin. Results are shown in supplemental Figure 14. There was no difference in bleeding events in patients with stage 1 or 2 CKD (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.54-1.30; P = .43). DOAC use was associated with decreased odds of bleeding in patients with stage 3 CKD (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.22-0.88; P = .02), stage 4 or 5 CKD (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51-0.86; P = .002), and patients on dialysis (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.47-0.72; P < .001).

There were 30 non-RCT studies with 61 333 total patients that assessed stroke incidence in patients of ≥1 specific CKD stages (supplemental Figure 15). There were 3 studies with 24 060 patients who had stage 1 or 2 CKD, 5 studies with 11 157 patients who had stage 3 CKD, 12 studies with 7117 patients who had stage 4 or 5 CKD, and 17 studies with 18 945 patients who were on dialysis. Subgroup analyses found no significant difference between DOAC use and the incidence of stroke for all subgroups: stage 1 or 2 CKD (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.78-1.17; P = .67), stage 3 CKD (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.26-1.52; P = .31), stage 4 or 5 CKD (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17; P = .20), and dialysis (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.33-2.46; P = .83).

Patients with concomitant AF and valve disease

The analysis of patients with concomitant AF and valve disease included 6 RCTs and 23 non-RCTs including a total of 99 299 patients, with 4947 patients in RCTs and 94 352 patients in non-RCTs.

Bleeding events

Overall, GI, and intracranial bleeding events were assessed. Overall bleeding was assessed in 4 RCTs and 11 non-RCTs, including 6851 participants and 91 596 participants, respectively. There were no significant differences between warfarin and DOACs in the RCTs (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.61-1.31; P = .56), but results favored DOACs in non-RCTs (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.97; P = .03; supplemental Figure 16).

Non-RCTs demonstrated no significant differences between warfarin and DOACs for GI bleeding (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.07-3.23; P = .44) and favored DOACs for intracranial bleeding (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.31-0.64; P < .001; supplemental Figures 17 and 18). The number of RCTs reporting GI and intracranial bleeding events was insufficient for statistical analysis.

Furthermore, when comparing warfarin and apixaban, there were no significant differences in overall bleeding in non-RCTs (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.01-9.56; P = .48; supplemental Figure 19). The number of studies assessing other DOACs was insufficient for individual analyses.

Stroke incidence

The incidence of overall stroke and TIA between warfarin and DOAC users was evaluated in 3 RCTs including 2123 participants and 14 non-RCTs including 94 352 participants. For stroke, RCTs demonstrated no significant difference between warfarin and DOACs (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.56-1.36; P = .54), whereas non-RCTs favored DOACs (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.47-0.93; P = .02). Non-RCTs demonstrated no significant difference between warfarin and DOACs for TIA (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.68-1.64; P = .81; supplemental Figure 20). The number of RCTs reporting TIAs was insufficient for analysis.

Arterial/systemic embolism and all-cause mortality

Non-RCTs demonstrated no significant differences in arterial/systemic embolisms between warfarin and DOAC users (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 0.89-5.32; P = .09; supplemental Figure 21). The number of RCTs reporting this outcome was insufficient for analysis. Regarding all-cause mortality, there were no significant differences between warfarin and DOACs in both RCTs (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.67-1.17; P = .40) and non-RCTs (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.09; P = .14; supplemental Figure 22).

Subgroup analysis comparing patients with or without valve repair/replacement

In studies examining the number of bleeding events, there were 7 non-RCTs with 33 111 patients including those with valve disease who had a valve replacement or repair procedure and 3 non-RCTs with 37 960 total patients including patients who did not have procedures. DOAC use over warfarin use had no statistically significant association with differences in bleeding outcomes in patients who had repair or replacement (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.59-1.20; P = .34) or in a secondary subgroup of patients who specifically had bioprosthetic valve replacement (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.43-1.14; P = .40). DOAC compared to warfarin was associated with decreased bleeding in patients who did not have procedures (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98; P = .04; supplemental Figure 23).

Regarding stroke incidences, there were 10 non-RCTs with 33 637 total patients who had valve replacement or repair procedures and 5 non-RCTs with 60 715 patients who did not. DOAC use over warfarin use had no statistically significant association with differences in stroke incidence in patients who had repair or replacement (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.54-1.26; P = .38) or in a secondary subgroup of patients who specifically had bioprosthetic valve replacement (OR, 0. 68; 95% CI, 0.26-1.75; P = .42). DOAC compared to warfarin was associated with decreased stroke incidence in patients with valvular disease who did not have procedures (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.33-0.93; P = .02; supplemental Figure 24).

Discussion

Aging patient population often presents with increasing comorbidities, in particular CKD, which notably increases the risk of embolism and hemorrhage.14 Additionally, AF is also associated with a higher risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with CKD.15,16 Thus, it is important to consider how patients with concomitant CKD will respond to anticoagulation.15

Research into the use of DOACs in valvular AF is also limited.17 Unlike mechanical heart valves, bioprosthetic heart valves eliminate the need for lifelong warfarin therapy but not anticoagulation altogether.18 There is a high risk of thromboembolic events within 3 to 6 months after bioprosthetic valve surgery.19,20 Recently, some studies have suggested that DOACs could serve as a preferred alternative to warfarin in patients with AF and bioprosthetic valve replacements.21

In this study, we conducted an exhaustive systematic review of studies evaluating the use of DOACs in patients with AF with CKD or valvular disease, because such patients are usually either underrepresented or excluded from large-scale studies. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive study in this area.

There are several findings from our research. First, in patients with concomitant AF and CKD, we found that DOAC use was associated with a significant reduction in overall bleeding, particularly for patients with more severe CKD (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), as well as a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. The difference in outcomes regarding stage 1 or 2 CKD compared to more severe CKD could be related to the differential effects on pharmacokinetics, with more severe CKD being more likely to have an effect. Second, when analyzing specific DOACs in patients with concomitant AF and CKD, apixaban was associated with reduced overall bleeding and stroke incidence. Lastly, in patients with concomitant AF and valvular disease, DOAC use was also associated with significant reduction in bleeding and stroke incidence. Given the heterogeneity of patients with valvular disease, we completed a subgroup analysis that showed DOAC benefit was in patients who did not have replacement or repair procedures. Taken together, these findings suggest that DOACs are likely a reasonable option in these populations, however, these are still considered off-label indications by regulatory authorities.

Several previous systematic reviews have addressed similar research questions. However, despite these valuable contributions, important gaps remain. Existing reviews are limited by narrower inclusion criteria or smaller sample sizes, because new trials have only been completed more recently. This review builds upon and extends the current evidence base by incorporating a larger and more comprehensive data set.

We identified 4 previous meta-analyses examining patients with AF and CKD. Two earlier meta-analyses by Su et al and Chen et al included studies until 2020.22,23 Both found that DOACs may be superior to warfarin in early CKD but inferior or similar to warfarin in patients receiving dialysis. Kao et al, which included studies up until 2022, found DOACs are consistently superior to warfarin in bleeding and stroke outcomes, which is similar to our findings. Differences in findings are likely attributable to new evidence from studies that have since been published.24 A fourth meta-analysis by Kimachi et al focused mostly on patients with CKD stage 3 and found DOACs to be similar to warfarin.25 Compared to previous meta-analyses, our review included 80 studies, whereas the previous largest review, to our knowledge, by Kao et al24 included 42 studies.

Two previous meta-analyses by Gerfer et al26 and Zhang et al27 examined patients with concomitant AF and valvular disease. Gerfer et al found DOACs reduced major bleeding as well as stroke incidence in patients who have undergone valve repair or replacement.26 Zhang et al27 found DOACs and warfarin were associated with stroke risks in patients with mitral stenosis but did not differentiate whether the patients had underwent valve surgery. Building upon these findings, our review was able to include more recent studies (29 total studies compared to 6 and 5 in the prior meta-analyses, respectively), which allowed us to complete our subgroup analysis to differentiate between patients with and without valve surgery. Similar to these prior studies, we also acknowledge the heterogeneity of the valve disease population and that more trials are needed.27

Our study does have some limitations. Due to the nature of systematic reviews, we could not ensure that all the individual trials included in our analysis defined relevant outcomes in the same manner. In assessing bleeding events, 87% of studies reported bleeding events according to ISTH criteria. However, 13% used other definitions including the Cunningham bleeding algorithm or a local billing code specified for major bleeding. Although this may make the interpretation of the results more difficult, these other definitions are similar to ISTH criteria and are also widely accepted as appropriate outcomes for studies evaluating anticoagulants. Another limitation, as aforementioned, is the heterogeneity of valve disease population. Given the large number of studies included in our review, we were able to mitigate this to the best of our abilities by our subgroup analyses that separated patients with and without valve surgery and then those who received bioprosthetic mitral or aortic valves specifically. Additionally, our analysis of non-RCTs included observational cohort studies, which can lack adequate adjustment for confounders. This is particularly relevant for safety outcomes such as bleeding. Without access to individual patient data, we could not perform propensity score matching or other adjustments, so these findings should be interpreted cautiously. Lastly, we do acknowledge that there may be some extent of reporting bias present because not all studies reported all outcomes.

Our study also does identify areas that would benefit from further research. Specifically, there is a relative paucity of data examining specific DOACs or comparisons between them. In patients with concomitant AF and CKD, our study only identified apixaban as superior to warfarin in association with bleeding events, but more trials are needed before a clear clinical recommendation can be made. Similarly, our study identified differences in treatment responses of patients with specific CKD stages. More studies contrasting patients with early-stage CKD, late-stage CKD, or on dialysis will help in forming a stronger conclusion. In summary, our findings suggest that the use of DOACs may be appropriate in patients with CKD, particularly advanced CKD, as well as in those with AF with valvular disease, although these agents are not approved for use in such populations and formal regulatory studies are required.

Acknowledgments

A.L.-L. is an investigator of the Canadian Venous Thromboembolism Clinical Trials and Outcomes Research (CanVECTOR) Network. The CanVECTOR Network receives grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference CDT-142654).

Authorship

Contribution: A.L., C.W., A.E.I., and A.L.-L. contributed to literature search, conceptualization, analysis, and writing the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alejandro Lazo-Langner, Hematology Division, London Health Sciences Centre, Victoria Hospital, 800 Commissioners Rd E Rm E6-216, London, ON N6A 5W9, Canada; email: alejandro.lazolangner@lhsc.on.ca.

References

Author notes

The data sets generated and analyzed during this systematic review and meta-analysis are available upon request from the corresponding author, Alejandro Lazo-Langner (alejandro.lazolangner@lhsc.on.ca).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.