Key Points

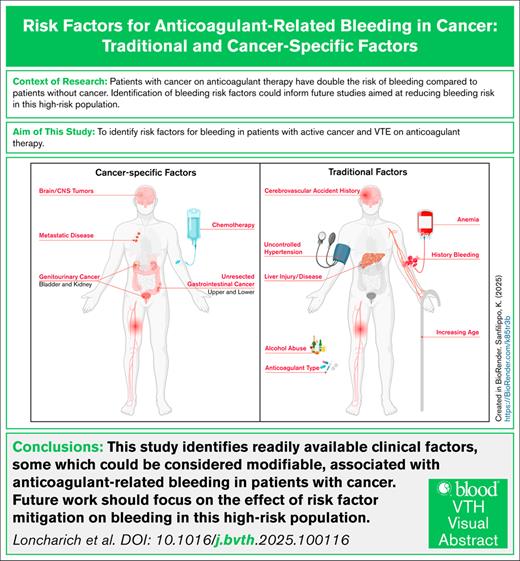

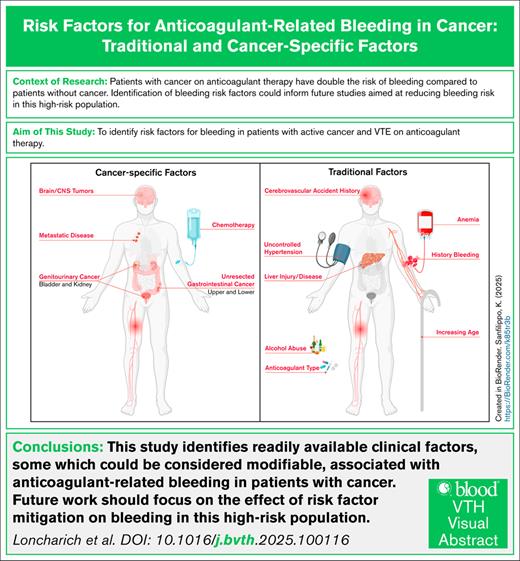

Readily available risk factors, some of which could be considered modifiable, are associated with anticoagulant-related bleeding in cancer.

Future studies focused on mitigation of modifiable risk factors associated with the risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding are needed.

Visual Abstract

Managing anticoagulant therapy in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) is challenging due to risks of recurrent VTE and anticoagulant-related bleeding. Existing clinical risk models for bleeding are limited by discriminatory ability in patients with cancer, perhaps due to the omission of cancer-specific risk factors for bleeding. This study estimated the associations of traditional and cancer-specific risk factors with bleeding requiring hospitalization in patients with cancer-associated VTE prescribed anticoagulant therapy. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Veterans Health Administration database to identify patients with cancer-associated VTE between 2012 and 2020. Cancer-associated VTE was defined by diagnostic International Classification of Diseases codes and the prescription of anticoagulant therapy within 30 days of VTE. The primary outcome was bleeding resulting in hospitalization. Traditional and cancer-specific risk factors were assessed using the methods of Fine and Gray, with death as a competing event. Among 11 151 patients with cancer-associated VTE, 869 patients (8.5%) experienced bleeding within 12 months of anticoagulant therapy. The most common bleeding sites were gastrointestinal (56.3%) and genitourinary tract (20.1%). Significant risk factors included age, alcohol abuse, anemia, liver injury or disease, uncontrolled hypertension, and history of bleeding. Cancer-specific risk factors included site of cancer, metastatic disease, and systemic cancer therapy. This study identifies readily available clinical risk factors associated with anticoagulant-related bleeding requiring hospitalization in patients with cancer-associated VTE. Among the identified variables, some could be considered modifiable. Identification and mitigation of risk factors for anticoagulant-related bleeding could guide management of anticoagulant therapy in this high-risk patient population.

Introduction

Management of anticoagulant therapy remains a challenge as patients with cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) are at high risk of both recurrent VTE and anticoagulant-related bleeding.1-3 Anticoagulant-related bleeding in patients with cancer has significant morbidity and mortality, with the case fatality rate exceeding 10%.4 In addition, anticoagulant-related bleeding is associated with unplanned hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, need for invasive procedures, and interruption of cancer therapies.5 Therefore, initiation and maintenance of anticoagulant therapy in patients with cancer requires careful assessment of the risk of bleeding.

The existing models for anticoagulant-related bleeding poorly discriminate (area under the curve of ≤0.60) bleeding risk in patients with cancer.6-8 The poor discrimination could be due to the failure of most models to incorporate cancer-specific risk factors. For example, tumor type and location are associated with risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding, with gastrointestinal (GI), genitourinary (GU), and intracranial tumors all associated with increased risk.9-12 Furthermore, there is a paucity of data on the association between traditional risk factors for anticoagulant-related bleeding (eg, anemia, renal disease, etc) and bleeding among patients with cancer.

Thus, we evaluated the predictive association of traditional and cancer-specific risk factors with bleeding requiring hospitalization in a large, real-world cohort of patients with cancer-associated VTE receiving anticoagulant therapy.

Materials and methods

Cohort

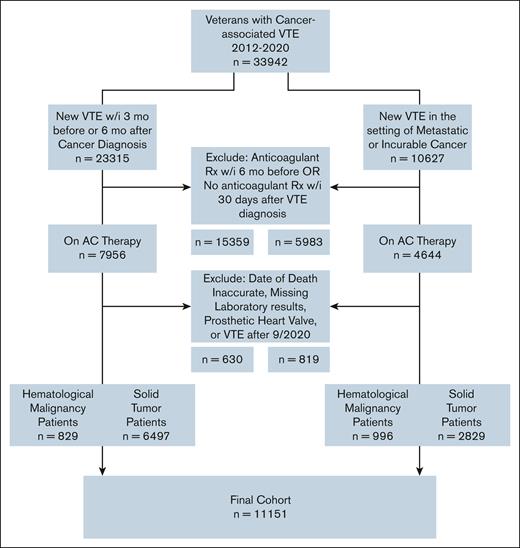

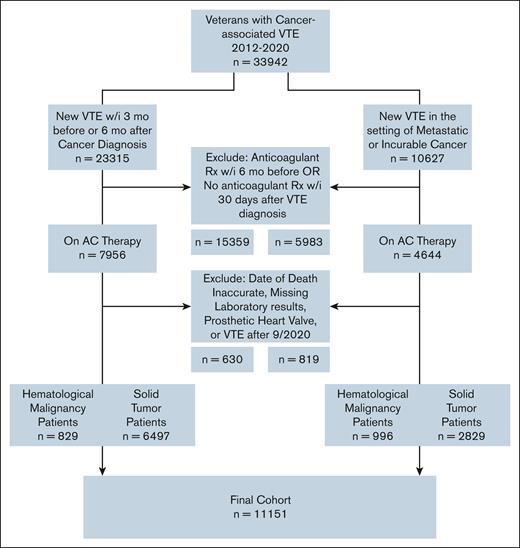

Using a retrospective, nationwide cohort of US Veterans, we identified patients with active cancer and newly diagnosed VTE between 2012 and 2020. We identified cancer using the presence of ≥2 International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th revisions (ICD-9/10) codes from the same primary site (supplemental Table 1). Using a previously validated algorithm,13 cancer-associated VTE was defined using a combination of ICD-9/10 codes for VTE (from both inpatient and outpatient encounters) plus at least 1 prescription of ≥30-day supply for anticoagulant therapy dispensed within 30 days of VTE diagnosis (positive predictive value 91%, sensitivity 72%). Candidate anticoagulant prescriptions included direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), fondaparinux, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or vitamin K antagonist. We considered cancer to be active at the time of VTE if any of the following criteria were met: (1) VTE occurring within 3 months before or 6 months after a cancer diagnosis, or (2) VTE occurring at any time after the diagnosis of metastatic or incurable (ie, multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, etc) cancer. To include patients with a clear temporal relationship between VTE diagnosis and anticoagulant therapy prescription, we excluded patients with outpatient prescriptions for anticoagulant therapy within 6 months preceding cancer-associated VTE. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a prosthetic heart valve, start of anticoagulant therapy after the cutoff date of 30 September 2020, inaccurate date of death (date of death before the date of cancer-associated VTE), and missing laboratory data.

Candidate variables

Patient-level variable and outcome data were obtained by linking multiple Corporate Data Warehouse domains within the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Traditional predictive factors for bleeding requiring hospitalization were selected a priori from existing risk prediction models for anticoagulant-related bleeding and other evidence.14-17 Cancer-specific factors were similarly selected.9,18 A definition of each predictive factor is listed in supplemental Table 1.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of interest was bleeding requiring hospitalization, defined as anticoagulant-related bleeding resulting in a hospital admission. We identified bleeding requiring hospitalization using a previously validated algorithm of inpatient ICD-9/10 codes for bleeding with requirements for ICD position (ie, primary, secondary, any position) dependent on the type of bleed coded (eg, intracranial hemorrhage [ICH], epistaxis, etc; supplemental Table 2).19 Patients were followed from time 0 (start date of anticoagulant therapy) to either (1) first bleed requiring hospitalization, (2) discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy (30 days after last anticoagulant prescription), (3) lost to follow-up defined as 6 months from date of last encounter, (4) death, or (5) end of study follow-up (30 September 2021), whichever occurred first.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with bleeding within 12 months of start of anticoagulant therapy and those without were descriptively listed. Twelve-month cumulative incidence of bleeding was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method and Gray test. Using the methods of Fine and Gray, we measured the predictive association between candidate variables and bleeding requiring hospitalization while accounting for the competing risk of death.20 Candidate variables with a P value of < .05 or a P value of < .10 if consistent with prior literature in univariate analyses were offered into the multivariable Fine and Gray model. We retained candidate variables in the multivariable model using backward regression until all remaining variables had a P value of .05. All analyses were completed using SAS EG 8.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the St. Louis Veterans Health Administration Medical Center and Washington University School of Medicine institutional review boards. Given the retrospective nature of this study, a waiver of informed consent was obtained before the study.

Results

We identified a cohort of 11 151 patients with cancer-associated VTE, of whom 9326 had solid tumor and 1825 hematologic cancers (Figure 1). Of the 11 151 patients, lung (23.2%), prostate (11.1%), and colorectal (9.4%) cancers were the most common solid tumors. Hematologic cancers comprised 16.4% of the cohort. Half of hematologic cancers (53.4%) were lymphoma. The median time from cancer diagnosis to VTE was 95 days (interquartile range [IQR], 10-374). Most patients received anticoagulant therapy with LMWH (46.7%), followed by DOACs (28.1%), vitamin K antagonists (24.3%), and fondaparinux (1%). DOAC use increased over time; DOAC prescriptions accounted for half of the anticoagulant therapy in 2018 and 76% of the anticoagulant therapy in 2020. The median available follow-up for the entire cohort was 425 days (IQR, 101-1255). At 12 months, 57% of the cohort remained alive (n = 6361). The median duration of anticoagulant therapy was 200 days (IQR, 71-365).

Within 12 months of starting anticoagulant therapy, 869 patients had a bleeding event requiring hospitalization for a 12-month cumulative incidence of 8.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.0-9.0). This translates to 211 events per 1000 patient years of anticoagulant therapy. The median time from start of anticoagulant therapy to bleeding event requiring hospitalization was 46 days (IQR, 14-139). Within 30 days, 41% of bleeding events had occurred (n = 356), increasing to 70.1% (n = 609) by 90 days after start of anticoagulant therapy. The cumulative incidence of bleeding was higher for patients with solid tumors (9.1% [95% CI, 8.4-9.7]; n = 746 patients) compared with hematologic cancers (7.3% [95% CI, 6.1-8.6]; n = 123 patients). For individual cancer types, unresected lower GI cancers, brain/central nervous system (CNS) tumors, and kidney/bladder tumors had the highest cumulative incidence of bleeding (Figure 2). The most common sites of bleeding were the GI tract (n = 489 [56.3%]), the GU tract (n = 175 [20.1%]), and ICH (n = 93 [10.7%]). When baseline patient characteristics were assessed, patients with bleeding events requiring hospitalization were more likely to have a history of alcohol abuse, anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL), a history of bleeding, and uncontrolled hypertension (Table 1). In addition, they were more likely to have metastatic disease and to be receiving systemic cancer therapy (Table 1).

Twelve-month cumulative incidence of bleeding by cancer type. Other cancers include bone/connective tissues (n = 140), thyroid (n = 61), testicular (n = 42), thymus/heart/mediastinum (n = 24), penis (n = 23), retroperitoneal/peritoneum (n = 19), Kaposi (n = 8), and ocular (n = 6). ∗Cumulative incidence for the entire cohort (cumulative incidence, 8.5% [95% CI, 8.0-9.0]). CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Twelve-month cumulative incidence of bleeding by cancer type. Other cancers include bone/connective tissues (n = 140), thyroid (n = 61), testicular (n = 42), thymus/heart/mediastinum (n = 24), penis (n = 23), retroperitoneal/peritoneum (n = 19), Kaposi (n = 8), and ocular (n = 6). ∗Cumulative incidence for the entire cohort (cumulative incidence, 8.5% [95% CI, 8.0-9.0]). CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Table 2 displays the univariate analyses measuring the predictive association between traditional predictive variables and bleeding requiring hospitalization in the full cohort (n = 11 151). Traditional variables predictive of bleeding requiring hospitalization included: age, alcohol abuse, anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL), anticoagulant type of therapy, concurrent antiplatelet therapy prescriptions, history of bleeding, history of a cerebrovascular accident, liver injury or disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate of <30 mL/min, race, and uncontrolled hypertension.

The predictive association between cancer-specific variables and bleeding requiring hospitalization is summarized in the univariate analyses results in Table 2. In the cohort, cancer type was predictive of bleeding, with an increased risk associated with brain/CNS, unresected upper GI, unresected lower GI, and GU cancers, whereas head and neck, lung, and lymphoma were associated with reduction in risk. Use of any systemic cancer therapy (including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy) was associated with a 28% increase in risk of bleeding; vascular endothelial growth factor therapy was also associated with a relative increase in the risk of bleeding. Finally, metastatic disease conferred a 35% increment in the risk of bleeding.

When combining the traditional and cancer-specific risk factors, 11 variables remained significant in the competing risk multivariable analysis. Variables associated with an increased risk of bleeding requiring hospitalization included: age, alcohol abuse, anemia, history of bleeding, history of cerebrovascular accident, liver injury or disease, uncontrolled hypertension, cancer type, chemotherapy, and metastatic disease. Anticoagulant therapy with DOAC was associated with a 24% reduction in the risk of bleeding when compared with warfarin. The results of the multivariable analysis are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

The cumulative incidence of anticoagulant-related bleeding requiring hospitalization within 12 months of start of anticoagulant therapy for treatment of cancer-associated VTE was 8.5%, with higher rates for patients with solid tumor (9.1%) vs patients with hematologic cancers (7.3%). The most common bleeding sites were the GI (56.3%) and GU (20.1%) tracts. Because of different definitions (eg, bleeding) and durations of follow-up, it is difficult to directly compare these rates with rates in randomized trials of cancer-associated VTE. However, as expected, the rates from this real-world cohort average higher. In the Hokusai VTE Cancer trial, the 12-month rates of bleeding were 6.9% with a DOAC and 4.0% with an LMWH.22 In the CARAVAGGIO trial, the 6-month risks of major bleeding were 3.8% with a DOAC and 4.0% with an LMWH.23 Our rates are comparable to other studies analyzing real-world data. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported a rate of bleeding in cancer-associated VTE of 13.1 per 100 patient years.4

Estimation of an individual’s propensity to bleed based on the presence of predictive factors identified in this analysis may facilitate informed discussions regarding initiation and maintenance of anticoagulant therapy. Predictive risk-factor identification can allow for quantification of bleeding risk in this tenuous patient population. In this study, 11 readily available clinical variables were identified in a large, diverse cohort of United States Veterans. The identified variables consist of a combination of traditional factors (ie, risk factors incorporated into existing risk prediction models for anticoagulant-related bleeding) and cancer-specific factors. Future efforts will be made to quantify a patient’s risk of bleeding based on the presence of these predictive factors.

Verification and/or assessment of previously identified predictive traditional risk factors and bleeding requiring hospitalization in cancer is important. First, certain populations were excluded from the randomized clinical trials evaluating anticoagulant therapy in cancer-associated VTE, potentially lowering the rate of anticoagulant-related bleeding in these trials. These populations include patients with traditional predictive factors for bleeding, such as anemia, chronic kidney, and liver disease.22,24-27 These variables are all associated with risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding in the general population.14-17 Furthermore, they are prevalent in patients with cancer, with ≤90% of patients with cancer on therapy being anemic in some studies,28 chronic kidney disease affecting at least 1 in 10 patients with cancer,29 and liver injury or disease affecting >1.5 billion persons globally.30 As expected, anemia and liver disease were associated with bleeding requiring hospitalization in this study. Estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min was associated with bleeding risk in univariate analysis; however, it was not in multivariable analysis. It is possible that the increasing preference for DOAC prescription modified this association in our study. Alcohol abuse can contribute to bleeding risk directly31 or indirectly via risky behavior, as well as liver injury or disease with portal hypertension, etc. Future explorations will focus on how these associations are modified in subpopulations with cancer.

In addition to comorbidities, our study identified variables that could be modified or prompt additional risk-benefit discussions at the time of anticoagulation prescription. One such variable includes alcohol abuse, which was predictive of bleeding in our study. Additionally, modifiable variables also include selection of type of anticoagulant therapy (DOAC: subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.92) and uncontrolled hypertension (sHR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.06-1.39). Although not significant in the multivariable analysis, antiplatelet prescriptions (ie, aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor) were associated with risk of anticoagulant bleeding in univariate analysis. Although such research as ours cannot identify causal sources of bleeding requiring hospitalization in cancer, future efforts can assess modifying these factors and the resultant association with changes in risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding. Such modifications could include control of hypertension, intentional selection of anticoagulant choice, or discontinuation of concurrent antiplatelet therapy (when feasible). Furthermore, additional variables predictive of bleeding could trigger early investigation to assess for existing sources of bleeding such as anemia and preexisting GI sources of bleeding (eg, gastric ulcer). Thus, although not causal, the identified predictive factors for bleeding can inform clinical practice.

In addition to traditional factors, we identified cancer-specific risk factors for bleeding. Type of cancer had significant implications on bleeding risk in this patient population. The presence of a brain tumor/CNS malignancy was associated with a twofold increase in the risk of bleeding (sHR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.50-3.94). These findings are consistent with a prior systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrating that anticoagulant therapy in patients with primary brain tumors increases the risk of ICH (odds ratio, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.42-9.95).32 The second most common site of bleeding in our cohort was bleeding from the GU tract. Accordingly, we found a 75% increase in the risk of bleeding requiring hospitalization for patients with GU tumors (sHR, 1.75 [95% CI, 1.44-2.13]). Higher rates of bleeding in patients with GU tumors were also noted in randomized trials of this patient population.10 More defined in the literature is the risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding in patients with GI tumors. For example, in the CARRAVAGIO trial, 36.5% of major bleeding events occurred in patients with GI tumors (upper GI, 11.1%; lower GI, 24.4%); of interest, all bleeding events in patients with GI tumors occurred in those with unresected tumors (n = 16/16).10 Our study supports this observation, with a significant association between risk of bleeding and unresected GI tumors (unresected upper GI: sHR, 1.53 [95% CI, 1.16-2.03]; and unresected lower GI: sHR, 1.47 [95% CI, 1.20-1.81]), but no association for those with resected tumors. Finally, the presence of metastatic disease and use of systemic therapy were also associated with increased risk of bleeding in our study.

We used the national Veterans Health Administration database for this study, allowing for compilation of a cohort of 11 151 patients with cancer-associated VTE. The sample size allowed analysis of a diverse collection of solid and hematologic malignancies bolstering generalizability. However, there are also limitations to using administrative databases. Identification of cancer diagnoses, outcome events, and medical comorbidities relied on accurate diagnosis codes, so data may be susceptible to misclassification, especially if care was received outside of the Veterans Administration (VA) system. In addition, some risk factors were not easily identified for appropriate evaluation. For example, surgery is a known risk factor for anticoagulant-related bleeding. Given the number of possible surgical procedures and the variation in bleeding risk associated with each one, analysis of surgery as a risk factor for anticoagulant-related bleeding was not pursued. Furthermore, while discontinuation of prescription of anticoagulant therapy was captured, we are unable to identify verbal instruction to hold anticoagulant therapy. Another limitation includes underrepresentation of women in this cohort, which also influences the distribution of cancer type; thus, our findings should be validated in a female population. Veterans may acquire care outside of the VA system, especially in emergent situations. As events outside of the VA system were not captured, this may have led to missing events such as bleeding events requiring hospitalization. In addition, if an initial prescription for anticoagulant therapy was supplied outside of the VA system, patients may have been misclassified as no anticoagulant therapy. Finally, our study is not designed to identify causality. All identified variables associated with risk of bleeding require further investigation to determine causality.

In conclusion, we identified readily available clinical risk factors associated with anticoagulant-related bleeding requiring hospitalization in patients with cancer-associated VTE. This included age, alcohol abuse, anemia, history of bleeding, history of cerebrovascular accident, liver injury or disease, uncontrolled hypertension, cancer type, chemotherapy, and the presence of metastatic disease. Of the identified variables, several could be considered modifiable or prompt further investigation into the presence of preexisting bleeding. Future studies could validate these findings, determine bleeding causality, and study the effect of risk-factor modification on bleeding outcomes in this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Washington University, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R01HL166386 and the American Society of Hematology (K.M.S.).

This study is the result of funding, in whole or in part, by the NIH. It is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy. Through acceptance of this federal funding, NIH has been given a right to make this article publicly available in PubMed Central upon the Official Date of Publication, as defined by NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: K.M.S. developed the initial study concept and assisted with coding for analysis; K.M.S., B.F.G., and S.L. designed the study; S.L. performed all analyses, with consultation by Y.Y. when appropriate; A.L. drafted the first version of the manuscript, followed by critical revision by all authors involved; and all authors interpreted the data with analytic revisions, recommended analytical revision accordingly, and granted final approval for submission and publication of the final manuscript version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S. reports consulting for ConcertAI. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kristen M. Sanfilippo, Hematology Division, Washington University, Mail Stop 8125-0022-01, 660 South Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63110; email: ksanfilippo@wustl.edu.

References

Author notes

Sharing of deidentified data for the presented population can be arranged upon request from the corresponding author, Kristen M. Sanfilippo (ksanfilippo@wustl.edu). Before data sharing, approval is required from the appropriate institutional review boards as well as the Veterans Administration. In addition, a data use agreement is required before any data transfer.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Twelve-month cumulative incidence of bleeding by cancer type. Other cancers include bone/connective tissues (n = 140), thyroid (n = 61), testicular (n = 42), thymus/heart/mediastinum (n = 24), penis (n = 23), retroperitoneal/peritoneum (n = 19), Kaposi (n = 8), and ocular (n = 6). ∗Cumulative incidence for the entire cohort (cumulative incidence, 8.5% [95% CI, 8.0-9.0]). CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NOS, not otherwise specified.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodvth/3/1/10.1016_j.bvth.2025.100116/1/m_bvth_vth-2025-000394-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1768580696&Signature=wXVB8dbQ2UOe-x7W96BhKJ8XChfAbc1egI8I-v98d3yNwuQGbYzGFQi3TvY4zhlyIcWAZ4s001lvmF63jD4Bg867QYWDnC1uzdmAWwuin6R9o~9NvkPNmYQuZ2WuQ6OVsn-awItYhROqpYln1o~IPwqaoWq0MYdK1Ou8KI-ejaX0fvTMQRzGjKj6JJDfCCDTVyQW2s5M04eXVO6Vjau61GnarC70oLRFm9P~xGwhaw-~zZ57~q8zPLoBMlYcgPjc8-5aLIdBg4y0xBN7ZbKoJIxrmxKlt9lNYWvIJYxhQD6MlgCgKIe2ChhIVJDk4JuSgf9HnDCjOjka4mGYUlcCuA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Twelve-month cumulative incidence of bleeding by cancer type. Other cancers include bone/connective tissues (n = 140), thyroid (n = 61), testicular (n = 42), thymus/heart/mediastinum (n = 24), penis (n = 23), retroperitoneal/peritoneum (n = 19), Kaposi (n = 8), and ocular (n = 6). ∗Cumulative incidence for the entire cohort (cumulative incidence, 8.5% [95% CI, 8.0-9.0]). CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NOS, not otherwise specified.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodvth/3/1/10.1016_j.bvth.2025.100116/1/m_bvth_vth-2025-000394-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1768580697&Signature=PqZ7IvANFaSmBbUl3onlj3a3Gm-IjpjU-oZ-XR26z2CJdDSbcdKfLqaGdhzzZJr4KwYa9RD5sYGs2fj~7IiGxPq7OR7q~pNcKZjZL6jKx42rFFUBr7Uwmk1B7Q6lANt4P~1WfG0rYHIQyGBzZGzqoxB9bhfgNymuQoIqZ1Psrrt5ypEfLQ~TBxsjLgMUJXGpY7elQxaxA8xEI9Hz5ZaZroAWbWSvk9L5pOGdmyZTZMhqit5NHD3QVqolBzscwR0~4tATc~jte5HfitGojZqHs3eo8bkg5bjNSwGzJMGZdFuT1Hf1ZgND7l6x7BiUC6pGx5QeCpBzf9TDUV-e84PCHg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)