Key Points

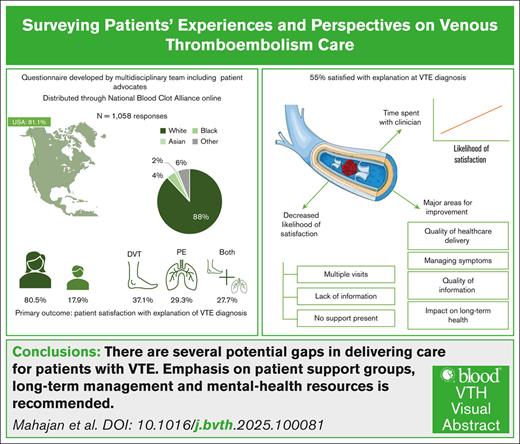

Only 55% of patients were satisfied with how their VTE diagnosis was explained at diagnosis.

Critical educational gaps exist regarding anticoagulation, long-term management, and support resources.

Visual Abstract

Patient experience is an independent dimension of health care delivery. We aimed to capture patients’ experiences with venous thromboembolism (VTE) to improve health care delivery. A survey was developed by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and patient advocates. Domains included patient demographics, health care experiences, perspectives, and potential gaps in health care received for VTE. The survey was distributed electronically between May and July 2023 through a patient advocacy group targeting individuals with a personal VTE history. The primary outcome was a binary indicator of patient satisfaction with how their VTE diagnosis was explained. Logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with satisfaction. Of 1050 participants, the majority were from the United States (81%). Most respondents were female (81%) and White (88%), and 71% were aged between 40 and 69 years. Satisfaction with clinician explanation of VTE diagnosis was reported in 55% of participants. The likelihood of satisfaction increased as the time spent with a clinician at diagnosis increased (relative to <5 minutes, risk ratio (RR) of 1.65 [95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36-2.02] for 6-10 minutes to RR of 2.44 [95% CI 1.92-3.10] for 31-60 minutes). Factors associated with decreased likelihood of satisfaction included multiple visits to obtain VTE diagnosis (RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.59-0.79) and not being given information at the time of diagnosis (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.61-0.79). From this large international survey designed to capture patient experiences and gaps in VTE care delivery, we identified several areas for improvement. Specifically, enhancing patient education and spending more time with patients at diagnosis are opportunities to improve patient satisfaction with VTE care.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), affects nearly 10 million people worldwide annually and is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.1-4 Randomized trials have mostly focused on clinical outcomes, including VTE recurrence and major bleeding, whereas data on patient-reported experience outcomes are more limited.

Patient satisfaction has been linked to improved communication with providers, patient trust, adherence, and, ultimately, health outcomes.5,6 Moreover, the patient experience and patients’ satisfaction with health care delivery is an independent dimension of health care quality across health systems.7,8 Although there is growing focus on patient-reported outcomes in VTE,9 data on patient experience and satisfaction with care are lacking. Identifying current gaps in health care delivery for VTE and identifying areas that affect patient satisfaction could drive improvements in patient-centered pathways to optimize care.10

We partnered with an international patient-run nonprofit advocacy organization, the National Blood Clot Alliance (NBCA), to conduct a cross-sectional study of patient experiences and gaps in VTE care delivery before, during, and after VTE diagnosis. This study represents a large-scale effort to quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate the experience of international VTE survivors.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, online survey study designed for individuals with a personal history of VTE. The institutional review board at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center deemed the study as human participants research exempt.

Study population/recruitment

The survey was distributed anonymously using a web-based platform, REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), between 1 May 2023 and 19 July 2023.11,12 Survey links were sent to members of the NBCA mailing list. In addition, institutional review board–approved posts were used on social media platforms to spread awareness of the study. Survey participants were invited to enter into an optional gift card raffle as an incentive to participate.

Data collection

A survey was designed by a multidisciplinary team that included clinicians, researchers with methodological expertise, and patient advocates. The survey included multiple-choice and open-ended questions (supplemental Appendix 1). The survey domains included the following: (1) participant demographics; (2) details of personal VTE history; (3) experiences with health care pertaining to care received for VTE, including details at the time of diagnosis, hospitalization, and postdischarge care; and (4) potential gaps in health care experiences and information received regarding VTE diagnosis. Participants were also asked to respond to the following 3 open-ended questions: (1) “tell us 3 things you wish to share with the health care community about your experience as a blood clot survivor”; (2) “share 3 things you wish a health care provider would have told you when you were first diagnosed with your blood clot”; and (3) “share 3 things you would like to tell an individual newly diagnosed with a blood clot.”

The study instrument was piloted and edited based on feedback from 7 patient volunteers for clarity, length, and relevance.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction with the explanation of their incident VTE diagnosis (yes/no). We selected a binary outcome to prioritize survey clarity and completion in a large, web-based population of lay participants. Secondary outcomes included receipt of printed or electronic information (at diagnosis or upon discharge from hospital); sources and quality of information received regarding anticoagulation and VTE diagnosis; and clinician specialists seen after VTE diagnosis.

Analyses

We summarized data as counts and proportions. We used log-binomial regression to assess whether the primary outcome varied by participant gender, age, race, education level, country, and care team composition; we present risks with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We then chose select variables based on subject matter expertise to include in a multivariable adjusted analysis, to explore factors that were significantly associated with the primary and secondary outcomes. We considered a 2-sided P value of <.05 to be statistically significant. We performed all analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

To identify themes in participants’ responses to open-ended questions, we performed a thematic content analysis.13,14 Two reviewers (A. Chan and C.M.) met in iterative rounds to review the open-ended responses, identify reliable key domains, and generate a codebook (supplemental Appendix 2) using 200 randomly selected responses (∼20%). Codes included deductive codes (determined a priori) and inductive codes that emerged from the text. Remaining responses were then analyzed with the codebook to iteratively identify additional codes. All open-ended responses were reviewed. The research team met virtually to organize codes to reflect major themes. Disagreement about the meaning of themes or codes was resolved by discussion and resulting consensus. Representative quotes were selected to illustrate themes.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 1058 participants completed the survey and were included in the analysis. A response rate could not be calculated given that the web-based survey was openly distributed. Participant demographics are summarized in Table 1. Most participants (81.1%) were from the United States (including 49 states and the District of Columbia), and most (81.1%) identified as female. Age at the time of the survey was reported as a range; 70.5% of participants were aged between 40 and 69 years. The majority of participants were White (88.3%), followed by Black/African American (4.5%) and Asian (1.5%), and 61.7% had earned at least a bachelor’s degree. Table 2 provides details regarding the incident VTE event. Most patients were diagnosed with a VTE in the emergency department (61.8%). PE was the most represented location (37.1%), followed by DVT (29.3%), and 27.7% of participants presented with both PE and DVT. The majority (59.4%) were aged <50 years at the time of VTE diagnosis. Most patients (68.6%) experienced their first VTE event >12 months before the study, and 36.3% had >1 VTE event (among whom 65.1% had 2 VTE events at the time of the survey).

Participant demographics

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Age at time of survey, y | |

| 18-29 | 53 (5.0) |

| 30-39 | 142 (13.5) |

| 40-49 | 250 (23.8) |

| 50-59 | 280 (26.6) |

| 60-69 | 212 (20.2) |

| ≥70 | 115 (10.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 852 (80.5) |

| Male | 189 (17.9) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (0.3) |

| Prefer to not answer | 14 (1.3) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 16 (1.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6 (0.6) |

| Black or African American | 47 (4.5) |

| White | 929 (88.3) |

| >1 | 21 (2.0) |

| Other | 14 (1.3) |

| Prefer to not answer | 19 (1.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 43 (4.1) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 16 (1.5) |

| High school degree or GED | 87 (8.3) |

| Some college | 262 (24.9) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 355 (33.7) |

| Graduate degree | 295 (28.0) |

| Prefer to not respond/missing | 43 (40.8) |

| Living in the United States | 858 (81.1) |

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Age at time of survey, y | |

| 18-29 | 53 (5.0) |

| 30-39 | 142 (13.5) |

| 40-49 | 250 (23.8) |

| 50-59 | 280 (26.6) |

| 60-69 | 212 (20.2) |

| ≥70 | 115 (10.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 852 (80.5) |

| Male | 189 (17.9) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (0.3) |

| Prefer to not answer | 14 (1.3) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 16 (1.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6 (0.6) |

| Black or African American | 47 (4.5) |

| White | 929 (88.3) |

| >1 | 21 (2.0) |

| Other | 14 (1.3) |

| Prefer to not answer | 19 (1.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 43 (4.1) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 16 (1.5) |

| High school degree or GED | 87 (8.3) |

| Some college | 262 (24.9) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 355 (33.7) |

| Graduate degree | 295 (28.0) |

| Prefer to not respond/missing | 43 (40.8) |

| Living in the United States | 858 (81.1) |

Data are shown as n (%). Data are missing for age at the time of survey (n = 6), gender (n = 7), race (n = 6), Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (n = 20), and the highest level of education (n = 4).

GED, general educational development.

Details of the VTE event

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Time of diagnosis of first blood clot | |

| <4 weeks before survey | 55 (5.2) |

| 4-12 weeks before survey | 66 (6.3) |

| 3-12 months before survey | 209 (19.8) |

| >12 months before survey | 726 (68.8) |

| Age at VTE diagnosis, y | |

| 18-29 | 153 (14.5) |

| 30-39 | 209 (19.8) |

| 40-49 | 264 (25.1) |

| 50-59 | 210 (19.9) |

| 60-69 | 160 (15.2) |

| ≥70 | 57 (5.4) |

| Diagnosed with blood clots more than once | 381 (36.3) |

| 2 diagnoses | 248 (65.1) |

| 3 diagnoses | 74 (19.4) |

| ≥4 diagnoses | 59 (15.5) |

| Location of diagnosis of first blood clot | |

| Emergency department | 653 (61.8) |

| At the doctor’s office | 148 (14.0) |

| While admitted to the hospital | 69 (6.5) |

| At urgent care | 66 (6.2) |

| Contacted by doctor after a visit | 64 (6.1) |

| Other | 57 (5.4) |

| Site of the VTE | |

| PE | 392 (37.1) |

| DVT | 309 (29.3) |

| Both | 293 (27.7) |

| Other | 62 (5.9) |

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Time of diagnosis of first blood clot | |

| <4 weeks before survey | 55 (5.2) |

| 4-12 weeks before survey | 66 (6.3) |

| 3-12 months before survey | 209 (19.8) |

| >12 months before survey | 726 (68.8) |

| Age at VTE diagnosis, y | |

| 18-29 | 153 (14.5) |

| 30-39 | 209 (19.8) |

| 40-49 | 264 (25.1) |

| 50-59 | 210 (19.9) |

| 60-69 | 160 (15.2) |

| ≥70 | 57 (5.4) |

| Diagnosed with blood clots more than once | 381 (36.3) |

| 2 diagnoses | 248 (65.1) |

| 3 diagnoses | 74 (19.4) |

| ≥4 diagnoses | 59 (15.5) |

| Location of diagnosis of first blood clot | |

| Emergency department | 653 (61.8) |

| At the doctor’s office | 148 (14.0) |

| While admitted to the hospital | 69 (6.5) |

| At urgent care | 66 (6.2) |

| Contacted by doctor after a visit | 64 (6.1) |

| Other | 57 (5.4) |

| Site of the VTE | |

| PE | 392 (37.1) |

| DVT | 309 (29.3) |

| Both | 293 (27.7) |

| Other | 62 (5.9) |

Data are shown as n (%). Data are missing for the time of diagnosis of first blood clot (n = 2), age at VTE diagnosis (n = 5), multiple VTE diagnoses (n = 8), location of diagnosis (n = 1), and site of VTE (n = 2).

Patient experiences at diagnosis

Most patients (93.5%) recalled that information about their VTE diagnosis was provided by physicians or advanced practitioners, and 64.7% reported that this conversation lasted ≤10 minutes (Table 3). Nearly half of the respondents (48.1%) reported being alone at the time of the VTE diagnosis, and 50.6% reported an incomplete understanding of their VTE diagnosis after the initial visit. Nearly 30% of respondents reported not receiving the correct diagnosis the first time they presented to medical care, and of these 311 participants, 59% required at least 3 health care encounters before receiving the correct diagnosis. Nearly 28% of participants responded that they did not feel their signs and symptoms of VTE were taken seriously upon initial presentation, with reported bias believed to be related to age (46.8%), gender or sex (19.1%), race/ethnicity (3.1%), and lack of health insurance (2.7%). Approximately half of respondents (53%) reported telehealth access to providers for questions regarding their VTE event after diagnosis.

Provider interactions regarding the VTE event

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Source of information regarding first blood clot diagnosis∗ | |

| Doctor, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner | 989 (93.5) |

| Nurse | 133 (12.6) |

| Friend or family member | 64 (6.0) |

| Patient advocate | 7 (0.7) |

| Social worker | 3 (0.3) |

| Other | 70 (6.6) |

| Time spent with provider when told about the first blood clot diagnosis | |

| ≤5 minutes | 257 (24.3) |

| 6-10 minutes | 343 (37.0) |

| 11-20 minutes | 160 (17.3) |

| 21-30 minutes | 90 (9.7) |

| 31-60 minutes | 32 (3.5) |

| >60 minutes | 45 (4.9) |

| Alone at the time of diagnosis | 507 (48.1) |

| Did you understand your diagnosis when it was first told to you? | |

| Yes, completely | 188 (17.9) |

| Yes, for the most part | 332 (31.5) |

| Some of it made sense and some of it did not | 213 (20.2) |

| Not entirely | 193 (18.3) |

| I was completely lost | 127 (12.1) |

| Visits needed for correct diagnosis | |

| 1 | 740 (70.4) |

| 2 | 127 (12.1) |

| 3 | 89 (8.5) |

| 4 | 44 (4.2) |

| ≥5 | 50 (4.8) |

| Felt signs and symptoms were taken seriously at first presentation | |

| Yes | 756 (72.1) |

| No | 293 (27.9) |

| Reasons why signs and symptoms not taken seriously (n = 293)∗ | |

| Young age | 126 (43.0) |

| Gender or sex | 56 (19.1) |

| Advanced age | 11 (3.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | 9 (3.1) |

| Lack of health insurance | 8 (2.7) |

| Race/ethnicity differed from that of health care provider | 6 (2.0) |

| Member of the LGBTQ+ community | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 175 (59.7) |

| Offered printed or electronic information at the time of first diagnosis | |

| Yes | 166 (15.7) |

| No | 695 (65.8) |

| Do not recall | 195 (18.5) |

| Type of information provided at the time of first diagnosis (n = 166)∗ | |

| Pamphlets/written material | 135 (81.3) |

| Website | 14 (8.4) |

| Electronic, such as a video | 4 (2.4) |

| Other | 9 (5.4) |

| Do not recall | 22 (13.3) |

| Topics of information provided at the time of first diagnosis (n = 166)∗ | |

| Follow-up recommendations | 107 (64.5) |

| Treatment options | 91 (54.8) |

| Causes | 81 (48.8) |

| Risk of death or disability | 53 (31.9) |

| Incidence | 30 (18.1) |

| Other | 7 (4.2) |

| Do not recall | 21 (12.7) |

| Appropriateness of information provided at first diagnosis (n = 166) | |

| Helpful and adequate in helping understand diagnosis | 80 (48.8) |

| Too basic, provided little knowledge | 62 (37.8) |

| Too complex and difficult to understand | 4 (2.4) |

| Do not recall | 18 (11.0) |

| Characteristic . | All participants (N = 1058) . |

|---|---|

| Source of information regarding first blood clot diagnosis∗ | |

| Doctor, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner | 989 (93.5) |

| Nurse | 133 (12.6) |

| Friend or family member | 64 (6.0) |

| Patient advocate | 7 (0.7) |

| Social worker | 3 (0.3) |

| Other | 70 (6.6) |

| Time spent with provider when told about the first blood clot diagnosis | |

| ≤5 minutes | 257 (24.3) |

| 6-10 minutes | 343 (37.0) |

| 11-20 minutes | 160 (17.3) |

| 21-30 minutes | 90 (9.7) |

| 31-60 minutes | 32 (3.5) |

| >60 minutes | 45 (4.9) |

| Alone at the time of diagnosis | 507 (48.1) |

| Did you understand your diagnosis when it was first told to you? | |

| Yes, completely | 188 (17.9) |

| Yes, for the most part | 332 (31.5) |

| Some of it made sense and some of it did not | 213 (20.2) |

| Not entirely | 193 (18.3) |

| I was completely lost | 127 (12.1) |

| Visits needed for correct diagnosis | |

| 1 | 740 (70.4) |

| 2 | 127 (12.1) |

| 3 | 89 (8.5) |

| 4 | 44 (4.2) |

| ≥5 | 50 (4.8) |

| Felt signs and symptoms were taken seriously at first presentation | |

| Yes | 756 (72.1) |

| No | 293 (27.9) |

| Reasons why signs and symptoms not taken seriously (n = 293)∗ | |

| Young age | 126 (43.0) |

| Gender or sex | 56 (19.1) |

| Advanced age | 11 (3.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | 9 (3.1) |

| Lack of health insurance | 8 (2.7) |

| Race/ethnicity differed from that of health care provider | 6 (2.0) |

| Member of the LGBTQ+ community | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 175 (59.7) |

| Offered printed or electronic information at the time of first diagnosis | |

| Yes | 166 (15.7) |

| No | 695 (65.8) |

| Do not recall | 195 (18.5) |

| Type of information provided at the time of first diagnosis (n = 166)∗ | |

| Pamphlets/written material | 135 (81.3) |

| Website | 14 (8.4) |

| Electronic, such as a video | 4 (2.4) |

| Other | 9 (5.4) |

| Do not recall | 22 (13.3) |

| Topics of information provided at the time of first diagnosis (n = 166)∗ | |

| Follow-up recommendations | 107 (64.5) |

| Treatment options | 91 (54.8) |

| Causes | 81 (48.8) |

| Risk of death or disability | 53 (31.9) |

| Incidence | 30 (18.1) |

| Other | 7 (4.2) |

| Do not recall | 21 (12.7) |

| Appropriateness of information provided at first diagnosis (n = 166) | |

| Helpful and adequate in helping understand diagnosis | 80 (48.8) |

| Too basic, provided little knowledge | 62 (37.8) |

| Too complex and difficult to understand | 4 (2.4) |

| Do not recall | 18 (11.0) |

Data are shown as n (%). Data are missing for the time spent with provider (n = 131), alone at diagnosis (n = 4), understanding of diagnosis (n = 5), visits needed for correct diagnosis (n = 7), symptoms taken seriously (n = 9), satisfaction with explanation (n = 10), offered information (n = 2), and appropriateness of information (n = 2). LGBTQ+, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, and Others.

Respondents could select >1 response option, and thus totals may sum to >100%.

A limited number of patients (n = 166 [15.7%]) received printed or electronic information immediately after VTE diagnosis (Table 3). Of these, most were provided written material (81.3%). Provided information included follow-up recommendations (64.5%), treatment options for VTE (54.8%), causes of VTE (48.8%), risk of morbidity and mortality related to VTE (31.9%), and incidence of VTE (18.1%). Some patients felt the information was too basic (37.8%), whereas 48.8% found it helpful in understanding the diagnosis; 11% did not recall whether the information was helpful.

Almost all participants (96.7%) were treated with anticoagulation, but only 48% recalled being provided specific information about the medication including risks and benefits. Only 23.9% of the 571 respondents who menstruate recall discussing the impact of anticoagulation on menstruation, and among those, more than half (55.2%) recalled discussing this only after developing anemia or changes in menstruation.

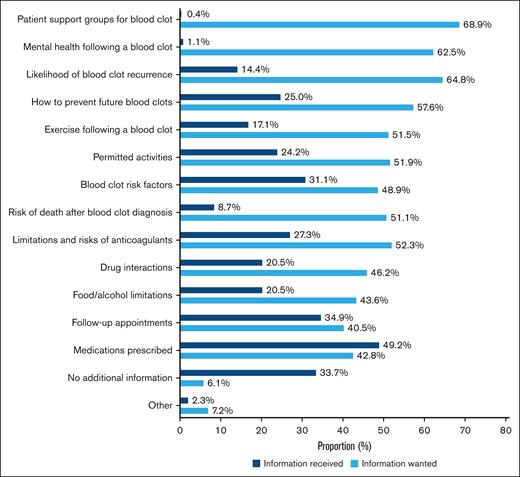

Of those treated for VTE in only the ambulatory setting (n = 264), most patients saw their primary physician (70.1%), 49.6% saw a hematologist/oncologist, 20.8% saw a vascular specialist, 14.4% saw a cardiologist, and 9.9% saw a pulmonologist after diagnosis. One-third of participants (34.2%) treated in the ambulatory setting received no specific information on VTE. For those who did receive information after their initial VTE treatment, the reported focus was on medications prescribed (49.2%) and follow-up appointments (34.98%), whereas the most frequently cited information desired included patient support groups for blood clots (68.9%), likelihood of blood clot recurrence (64.8%), and mental health resources after a blood clot diagnosis (62.5%; Figure 1).

Desired domains of information vs received information for patients diagnosed with VTE in the ambulatory setting. A total of 264 patients were included.

Desired domains of information vs received information for patients diagnosed with VTE in the ambulatory setting. A total of 264 patients were included.

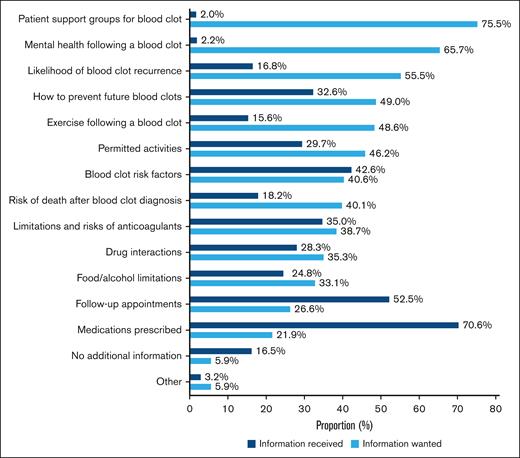

Patient experiences related to hospitalization for VTE

Of 715 patients admitted to the hospital at any time due to their VTE diagnosis, 34.2% were admitted for ≥5 days. Most admitted patients (83.5%) reported receiving information about VTE upon discharge, but the information provided did not match the information desired. For example, most patients wanted information regarding patient support groups for blood clots (75%) and mental health resources after a VTE (65.7%); however, only 2% and 2.2% of respondents were provided with this information, respectively. Patients also wanted information regarding VTE recurrence risk (55.5%) and prevention strategies (49%), but fewer received this type of information (16.8% and 32.6%, respectively; Figure 2). Reported information provided at discharge was focused on medications prescribed (70.6%) and follow-up appointments (52.5%). Among patients diagnosed in the emergency department or hospital (n = 722), only 9.4% were offered the opportunity to speak with a patient advocate after the incident VTE diagnosis. Of the 68 participants who were offered the opportunity to speak with a health care advocate, most (72.7%) accepted it; of those who were not offered an advocate (n = 652), 87.7% reported that they would have accepted the opportunity. During hospitalization, one-third of respondents (35.4%) were seen by a hematologist/oncologist, 34.6% were seen by a pulmonologist, and 33.3% were seen by a cardiologist (patients could be seen by multiple specialists). After discharge from the hospital, most patients followed up with their primary physician (64.3%), 58.8% saw a hematologist/oncologist, 33.1% saw a pulmonologist, 31.0% saw a cardiologist, and 18.5% saw a vascular specialist. After discharge, one-third (n = 229 [32.1%]) returned to a health care provider, emergency department, or urgent care because symptoms were worsening or not improving, and 30.1% of these patients (n = 69) were readmitted to the hospital.

Desired domains of information vs received information for patients diagnosed with VTE in the hospital or emergency department setting. A total of 715 patients were included.

Desired domains of information vs received information for patients diagnosed with VTE in the hospital or emergency department setting. A total of 715 patients were included.

Patient satisfaction and factors associated with satisfaction

Overall, slightly more than half of participants (55.0%) reported being satisfied with the explanation of the incident VTE event. Compared to the younger patients (aged 18-29 years), the oldest patients were significantly more likely to be satisfied (risk ratio [RR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09-1.39), and male respondents were significantly more likely to be satisfied than female respondents (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.09-1.39; Table 4). The likelihood of satisfaction increased proportionally as the time spent with the provider at diagnosis increased (relative to ≤5 minutes, ranging from RR of 1.65 [95% CI, 1.36-2.02] for 6-10 minutes to RR of 2.44 [95% CI, 1.92-3.10] for 31-60 minutes). Factors significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of satisfaction included being located outside the United States (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.80), not having a support person present at the time of diagnosis (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-0.98), needing >1 visit to obtain a diagnosis (RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.59-0.79), and not being given information at the time of diagnosis (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.61-0.79).

Factors associated with patient satisfaction with initial explanation of VTE diagnosis

| Outcome . | Satisfied, n (%) . | Risk ratio (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at VTE diagnosis, y | ||

| 18-29 (n = 153) | 78 (51.0) | Ref |

| 30-39 (n = 207) | 108 (52.2) | 1.02 (0.84-1.25) |

| 40-49 (n = 261) | 141 (54.0) | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) |

| 50-59 (n = 208) | 115 (55.3) | 1.08 (0.89-1.32) |

| 60-69 (n = 157) | 93 (59.2) | 1.16 (0.95-1.42) |

| ≥70 (n = 57) | 39 (68.4) | 1.34 (1.06-1.70) |

| Gender | ||

| Female (n = 845) | 446 (52.8) | Ref |

| Male (n = 188) | 122 (64.9) | 1.23(1.09-1.39) |

| Race/ethnicity∗ | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 876) | 488 (55.7) | Ref |

| Not non-Hispanic White (n = 126) | 61 (48.4) | 0.87 (0.72-1.05) |

| Location | ||

| United States (n = 851) | 499 (58.6) | Ref |

| International (n = 197) | 77 (39.1) | 0.67 (0.56-0.80) |

| Education | ||

| Less than a bachelor’s degree (n = 363) | 192 (52.9) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) |

| Bachelor’s degree or more (n = 643) | 364 (56.6) | Ref |

| Time since VTE diagnosis | ||

| <3 months before survey (n = 120) | 59 (49.2) | 0.87 (0.72-1.06) |

| 3-12 months before survey (n = 207) | 111 (53.6) | 0.95 (0.83-1.10) |

| >12 months before survey (n = 719) | 405 (56.3) | Ref |

| Site of VTE | ||

| PE (n = 388) | 213 (54.9) | 0.98 (0.86-1.13) |

| DVT (n = 308) | 170 (55.2) | 0.99 (0.86-1.14) |

| Both (n = 290) | 162 (55.9) | Ref |

| Location of VTE diagnosis | ||

| Emergency department/inpatient (n = 722) | 398 (55.5) | Ref |

| Ambulatory setting (n = 335) | 178 (53.8) | 0.97 (0.86-1.09) |

| Support person present at diagnosis | ||

| Yes (n = 543) | 317 (58.4) | Ref |

| No (n = 503) | 257 (51.1) | 0.88 (0.78-0.98) |

| Time spent with provider at diagnosis | ||

| 5 minutes or less (n = 255) | 85 (33.3) | Ref |

| 6-10 minutes (n = 341) | 188 (55.1) | 1.65 (1.36-2.02) |

| 11-20 minutes (n = 159) | 112 (70.4) | 2.11 (1.73-2.58) |

| 21-30 minutes (n = 88) | 63 (71.6) | 2.15 (1.73-2.67) |

| 31-60 minutes (n = 32) | 26 (81.3) | 2.44 (1.92-3.10) |

| >60 minutes (n = 45) | 33 (73.3) | 2.20 (1.72-2.82) |

| No. of visits to obtain a diagnosis | ||

| 1 (n = 731) | 444 (60.7) | Ref |

| >1 (n = 311) | 129 (41.5) | 0.68 (0.59-0.79) |

| Treatment location | ||

| Inpatient (n = 714) | 411 (58.1) | Ref |

| Ambulatory setting (n = 272) | 133 (49.4) | 0.85 (0.74-0.98) |

| Given information at diagnosis | ||

| Yes (n = 165) | 115 (69.7) | Ref |

| No (n = 689) | 333 (48.3) | 0.69 (0.61-0.79) |

| Do not recall (n = 193) | 127 (65.8) | 0.94 (0.82-1.09) |

| Outcome . | Satisfied, n (%) . | Risk ratio (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at VTE diagnosis, y | ||

| 18-29 (n = 153) | 78 (51.0) | Ref |

| 30-39 (n = 207) | 108 (52.2) | 1.02 (0.84-1.25) |

| 40-49 (n = 261) | 141 (54.0) | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) |

| 50-59 (n = 208) | 115 (55.3) | 1.08 (0.89-1.32) |

| 60-69 (n = 157) | 93 (59.2) | 1.16 (0.95-1.42) |

| ≥70 (n = 57) | 39 (68.4) | 1.34 (1.06-1.70) |

| Gender | ||

| Female (n = 845) | 446 (52.8) | Ref |

| Male (n = 188) | 122 (64.9) | 1.23(1.09-1.39) |

| Race/ethnicity∗ | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 876) | 488 (55.7) | Ref |

| Not non-Hispanic White (n = 126) | 61 (48.4) | 0.87 (0.72-1.05) |

| Location | ||

| United States (n = 851) | 499 (58.6) | Ref |

| International (n = 197) | 77 (39.1) | 0.67 (0.56-0.80) |

| Education | ||

| Less than a bachelor’s degree (n = 363) | 192 (52.9) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) |

| Bachelor’s degree or more (n = 643) | 364 (56.6) | Ref |

| Time since VTE diagnosis | ||

| <3 months before survey (n = 120) | 59 (49.2) | 0.87 (0.72-1.06) |

| 3-12 months before survey (n = 207) | 111 (53.6) | 0.95 (0.83-1.10) |

| >12 months before survey (n = 719) | 405 (56.3) | Ref |

| Site of VTE | ||

| PE (n = 388) | 213 (54.9) | 0.98 (0.86-1.13) |

| DVT (n = 308) | 170 (55.2) | 0.99 (0.86-1.14) |

| Both (n = 290) | 162 (55.9) | Ref |

| Location of VTE diagnosis | ||

| Emergency department/inpatient (n = 722) | 398 (55.5) | Ref |

| Ambulatory setting (n = 335) | 178 (53.8) | 0.97 (0.86-1.09) |

| Support person present at diagnosis | ||

| Yes (n = 543) | 317 (58.4) | Ref |

| No (n = 503) | 257 (51.1) | 0.88 (0.78-0.98) |

| Time spent with provider at diagnosis | ||

| 5 minutes or less (n = 255) | 85 (33.3) | Ref |

| 6-10 minutes (n = 341) | 188 (55.1) | 1.65 (1.36-2.02) |

| 11-20 minutes (n = 159) | 112 (70.4) | 2.11 (1.73-2.58) |

| 21-30 minutes (n = 88) | 63 (71.6) | 2.15 (1.73-2.67) |

| 31-60 minutes (n = 32) | 26 (81.3) | 2.44 (1.92-3.10) |

| >60 minutes (n = 45) | 33 (73.3) | 2.20 (1.72-2.82) |

| No. of visits to obtain a diagnosis | ||

| 1 (n = 731) | 444 (60.7) | Ref |

| >1 (n = 311) | 129 (41.5) | 0.68 (0.59-0.79) |

| Treatment location | ||

| Inpatient (n = 714) | 411 (58.1) | Ref |

| Ambulatory setting (n = 272) | 133 (49.4) | 0.85 (0.74-0.98) |

| Given information at diagnosis | ||

| Yes (n = 165) | 115 (69.7) | Ref |

| No (n = 689) | 333 (48.3) | 0.69 (0.61-0.79) |

| Do not recall (n = 193) | 127 (65.8) | 0.94 (0.82-1.09) |

Statistically significant values are shown in bold.

Ref, reference.

Excludes respondents with missing or unknown race and/or ethnicity.

Qualitative analysis

Most participants (n = 853 [80.6%]) answered at least 1 section of the 3 qualitative questions. Five major themes emerged from thematic content analysis of patient responses (Table 5). Four of the 5 major themes addressed areas for improvement: (1) quality of health care delivery; (2) managing symptoms; (3) impact on overall long-term health; and (4) quality of information/counseling. The fifth major theme identified through analysis was positive experience with diagnosis, such as clinicians quickly recognizing the severity and etiology of their symptoms. Patients highlighted the importance of timely diagnosis, costs of care, coordination of follow-up, and feeling that providers valued their concerns. Many patients wanted clinicians to recognize the burden of and offer more treatments for residual post-VTE symptoms. They also desired more awareness of and guidance about effects of VTE on their long-term mental health and/or reproductive health. Finally, participants emphasized the need for improved information-sharing on workup of VTE etiology, management of thrombosis and the associated risks, and thrombosis recurrence risk and long-term expectations.

Themes captured in open-ended questions and representative quotes

| General positive experiences | |

| “Providers that listened and took my symptoms seriously have saved my life twice (and my son's life as I was in the first trimester when I got my first blood clot).” [Respondent 617] “Radiologists and pharmacists are fantastic and are a massively under recognized when it comes to patient care. Without exception, in my interactions they have always been incredibly helpful, reassuring, calming and knowledgeable.” [Respondent 423] “I had an excellent hospital doctor. He sat with me every day and talked about the different types of clots I had.” [Respondent 769] | |

| Areas for improvement | |

| Health care delivery | |

| Validation of symptoms/lack of empathy | “I will take a blood thinner for the rest of my life. At diagnosis it was life threatening. Now doctors act like it’s no big deal.” [Respondent 64] |

| Delay in diagnosis | “I wish the maternity departments we're more educated on blood clots because maybe I would have been treated more appropriately and quickly.” [Respondent 836] |

| Access to health care/insurance | “I was in between insurance and was not directed to get follow-up care from the hospital had to find it myself.” [Respondent 192] |

| Coordination of care | “It caused me a lot of stress not knowing who to turn to. My nurse practitioner said it wasn't her. One of the other pcp docs wouldn't help either. I felt lost and frustrated.” [Respondent 729] |

| Awareness of disease/symptoms | |

| Pain/cramping | “I was unable to walk due to the pain in my groin and leg.” [Respondent 228] |

| Shortness of breath | “That often they don't know why this happened or how long I might be hospitalized. Most importantly, that I may never completely recover my breathing and might experience shortness of breath for the rest of my life.” [Respondent 274] |

| Fatigue | “I had to ask for ADA at work to help support my fatigue, brain fog, and stamina problems. I was on O2 for months afterwards.” [Respondent 512] |

| Advocate for self | “Pay attention to things that feel odd/not normal. Ask for information if you don’t understand something.” [Respondent 112] |

| Support groups | “There are groups like the NBCA who are available to support you and to hear it from real live people. Reach out to groups that can help you.” [Respondent 149] |

| Impact on long-term health | |

| Mental health | “The mental impact of DVT/PE post incident is real and life altering.” [Respondent 5] |

| Reproductive health | “I wish that the risks of contraception were talked about more, and the numbers were shown more clearly.” [Respondent 211] |

| Access to information | |

| Etiology and thrombophilia testing | “I wanted the genetic test to see if I had anything I have factor V Leiden. Now I wish I didn't know because it's a preexisting condition and excludes me from several things that actually could benefit me.” [Respondent 100] |

| Management | “My primary doctor had no clue how to monitor my INR while on Coumadin and had to find my own team.” [Respondent 8] |

| Recurrence and long-term expectations | “Nobody told me how long I’d feel this way. Nobody prepared me for what to expect longer term.” [Respondent 109] |

| Other not specified | “The meanings of terms like ‘unprovoked,’ ‘bilateral,’ ‘right heart strain,’ and what exactly those things meant. A glossary of common diagnosis terms for the lay person would be great because I spent time searching each word when I got home.” [Respondent 350] |

| General positive experiences | |

| “Providers that listened and took my symptoms seriously have saved my life twice (and my son's life as I was in the first trimester when I got my first blood clot).” [Respondent 617] “Radiologists and pharmacists are fantastic and are a massively under recognized when it comes to patient care. Without exception, in my interactions they have always been incredibly helpful, reassuring, calming and knowledgeable.” [Respondent 423] “I had an excellent hospital doctor. He sat with me every day and talked about the different types of clots I had.” [Respondent 769] | |

| Areas for improvement | |

| Health care delivery | |

| Validation of symptoms/lack of empathy | “I will take a blood thinner for the rest of my life. At diagnosis it was life threatening. Now doctors act like it’s no big deal.” [Respondent 64] |

| Delay in diagnosis | “I wish the maternity departments we're more educated on blood clots because maybe I would have been treated more appropriately and quickly.” [Respondent 836] |

| Access to health care/insurance | “I was in between insurance and was not directed to get follow-up care from the hospital had to find it myself.” [Respondent 192] |

| Coordination of care | “It caused me a lot of stress not knowing who to turn to. My nurse practitioner said it wasn't her. One of the other pcp docs wouldn't help either. I felt lost and frustrated.” [Respondent 729] |

| Awareness of disease/symptoms | |

| Pain/cramping | “I was unable to walk due to the pain in my groin and leg.” [Respondent 228] |

| Shortness of breath | “That often they don't know why this happened or how long I might be hospitalized. Most importantly, that I may never completely recover my breathing and might experience shortness of breath for the rest of my life.” [Respondent 274] |

| Fatigue | “I had to ask for ADA at work to help support my fatigue, brain fog, and stamina problems. I was on O2 for months afterwards.” [Respondent 512] |

| Advocate for self | “Pay attention to things that feel odd/not normal. Ask for information if you don’t understand something.” [Respondent 112] |

| Support groups | “There are groups like the NBCA who are available to support you and to hear it from real live people. Reach out to groups that can help you.” [Respondent 149] |

| Impact on long-term health | |

| Mental health | “The mental impact of DVT/PE post incident is real and life altering.” [Respondent 5] |

| Reproductive health | “I wish that the risks of contraception were talked about more, and the numbers were shown more clearly.” [Respondent 211] |

| Access to information | |

| Etiology and thrombophilia testing | “I wanted the genetic test to see if I had anything I have factor V Leiden. Now I wish I didn't know because it's a preexisting condition and excludes me from several things that actually could benefit me.” [Respondent 100] |

| Management | “My primary doctor had no clue how to monitor my INR while on Coumadin and had to find my own team.” [Respondent 8] |

| Recurrence and long-term expectations | “Nobody told me how long I’d feel this way. Nobody prepared me for what to expect longer term.” [Respondent 109] |

| Other not specified | “The meanings of terms like ‘unprovoked,’ ‘bilateral,’ ‘right heart strain,’ and what exactly those things meant. A glossary of common diagnosis terms for the lay person would be great because I spent time searching each word when I got home.” [Respondent 350] |

ADA, Americans with Disabilities Act; INR, International normalized ratio.

Discussion

In this large international survey of >1000 patients, we describe the patient experience with VTE diagnosis and care delivery. Nearly one-third of respondents reported not receiving the correct diagnosis at their initial presentation, and many required multiple visits before being diagnosed with VTE. Only 55% of participants reported satisfaction with how their incident VTE was explained; male respondents, older patients, and those whose providers spent more time at their diagnosis were more likely to report satisfaction. These results are similar to studies examining disclosure of cancer diagnosis that showed higher satisfaction scores for discussions lasting >10 minutes.15 Factors significantly associated with decreased satisfaction included not having a support person at the time of diagnosis, requiring multiple visits to obtain a diagnosis, and not being given information at the time of VTE diagnosis.

Our survey identified several potential health care delivery gaps. Patient satisfaction with VTE care has been linked to receipt of education about their health condition from their primary provider.16 A prior qualitative study also identified incomplete information during transitions and follow-up as a key theme.17 Similarly, in our study, few respondents reported receiving any additional printed or electronic information at the time of VTE diagnosis. When information was received, it focused primarily on follow-up recommendations, treatment options, and causes of VTE, despite the reported desire for information about advocacy groups and mental health resources. Patients also reported wanting information regarding VTE recurrence and prevention strategies, but this was rarely provided. When analyzing qualitatively, themes regarding quality of health care delivery, symptom management, impact on long-term health, and quality of information/counseling were identified. Patients highlighted the critical importance of timely diagnosis, costs of care, coordination of follow-up, and validation of their concerns.

Psychological and emotional distress are inversely correlated with patient satisfaction.18-20 Patients with a history of VTE experience significantly worse disease-related psychological distress,21 and VTE diagnosis is linked to psychosocial impacts, including depression,22 anxiety,23,24 and posttraumatic stress disorder.25 Similar to our study, participants in prior studies have described their care after VTE diagnosis as focused on biomedical information with limited attention given to psychological care and support groups. Apart from their role to increase public awareness, legislation, and research funding, patient advocacy groups are an important source for individual patient education, advocacy, and support services.26-28 This survey highlights the desire for patients to receive information about advocacy groups after VTE diagnosis; although only 9% reported being offered the chance to connect with a patient advocate, almost 90% reported they would have accepted such an opportunity should it have been offered.

Although this is, to our knowledge, the largest study surveying patient experiences related to VTE, there are several limitations to this study, including those inherent to a web-based survey design.29 Given the survey was distributed online, we were unable to calculate a response rate, which can be an important measure of response bias.30 Moreover, because participation was purely voluntary, the results could be influenced by respondent bias and less generalizable.31 Although the study was conducted internationally, most respondents were from the United States (81%), with all geographic states represented. Most participants (88.3%) self-identified as White, which is an overrepresentation of the United States non-Hispanic White population (61.6% from 2020 US Census data),32 and this may have affected the responses acquired. Although factors such as race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status have been shown to be linked to patient satisfaction in health care,33 we were unable to assess the impact of several of these factors given our study population distribution, despite the relatively large sample size.

The survey was sent to members of the NBCA mailing list and, therefore, may not be generalizable to the entire population of VTE survivors. For example, most respondents were women, and almost a third had >1 VTE event during their lifetime. Over one-third of respondents had a history of PE, and the majority were hospitalized at some time for their VTE diagnosis, which suggests this sample had higher acuity disease because most patients with DVT alone are treated solely in the outpatient setting.34 Furthermore, this group was more likely to express a desire for information about patient advocacy groups given their involvement with NBCA, and advocacy group members may be less satisfied with their initial VTE care than VTE survivors who are not part of an advocacy group. Moreover, most survey respondents were diagnosed with their first event >1 year before the survey, which may have contributed to recall bias, particularly because the primary outcome related to events at the time of VTE diagnosis, which is often a difficult time for patients to process information. Prior studies in other diseases such as cancer have shown that at time of diagnosis most patients do not understand prognosis or goal of treatment.35 The binary response format for the primary outcome (satisfaction with the explanation of the incident VTE diagnosis) limited our ability to disentangle specific contributing factors such as communication style, time spent with the provider, or clarity around causality. However, open-ended responses were included to explore these dimensions qualitatively. The yes/no format, as opposed to Liekert scale, did not permit us to observe a distribution. Identifying the cause of VTE can be challenging, and this may lead to dissatisfaction among survivors, which could lead to patients perceiving less time spent in discussion of the incident event. The majority of patients received their VTE diagnosis in the emergency department, and this may have contributed to some of the findings, given the acute care setting and limited time for discussion.

Few studies have explored the patient experience after VTE diagnosis, and there are limited qualitative data that have been analyzed on a large scale. In this international survey, many patients were not satisfied with the explanation provided at the time of their VTE event, and nearly one-third were misdiagnosed and required multiple health care encounters before receiving the correct diagnosis, with respondents reporting experiencing bias based on gender, race/ethnicity, age, and insurance status. Our quantitative and qualitative analysis identified several potential gaps in health care delivery, including providing information at the time of VTE diagnosis with a specific emphasis on patient support groups, long-term management and consequences, and mental health resources. A systems-based approach that provides multidisciplinary care including patient education, mental health resources, and anticoagulation support may be of benefit for patients because this has previously shown to be associated with patient satisfaction.36 More research on a broader scale with more diverse respondent pool is needed to identify how information regarding these important resources can best be delivered equitably to all patients diagnosed with VTE to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction in the care delivered for this important global health issue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Blood Clot Alliance, which assisted in distributing the survey to members. A.P. is supported by National Institute on Aging grant K76AG083304.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M. and R.P. drafted the manuscript; and all authors designed the study, acquired and analyzed data, made revisions to the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rushad Patell, Division of Hemostasis and Thrombosis, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: rpatell@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Rushad Patell (rpatell@bidmc.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.