Abstract

Patients with advanced follicular lymphoma (FL) have numerous treatment options, including observation, radiotherapy, single-agent or combination chemotherapy, mAbs, and radioimmunoconjugates. These therapies can extend progression-free survival but none can provide a cure. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) remains the only curable therapy for FL, with the field shifting more toward the use of reduced-intensity conditioning regimens because of the lower associated nonrelapse mortality compared with myeloablative regimens. However, GVHD and infection are still problematic in the allo-HSCT population. Autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) confers high response rates and prolongs progression-free survival in relapsed patients who are chemosensitive, and an increasing amount of data suggest that auto-HSCT may be curative if offered to relapsed patients who are not heavily pretreated. Auto-HSCT has no role as consolidation therapy for patients in first remission based on the results from 3 large randomized trials. Novel conditioning regimens with radioimmunoconjugates have been used in both auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT regimens and results have shown efficacy even in chemorefractory patients. Therefore, with the exception of patients in first remission, the optimal timing for HSCT remains controversial. However, the outcomes seen after auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT continue to improve, and HSCT represents a treatment modality that should be considered in all FL patients, especially while their disease remains chemoresponsive.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of approximately 15 000 new cases/year in the United States. The incidence increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis being 60 years. FL cells express surface Ig and the cell-surface markers CD19, CD20, and CD10. Also characteristic is cytoplasmic expression of the bcl-2 protein and the presence of the t(14;18) translocation involving the IgH/bcl-2 genes. The median survival rate from diagnosis has historically ranged from 8-10 years, and the availability of the chimeric anti-CD20 mAb rituximab (RTX) has improved outcome and survival.1 However, FL remains incurable with standard therapy and the clinical course among FL patients is markedly variable. Some patients develop progressive or transformed disease early, with 15% dying within 2 years from diagnosis, whereas others remain alive for decades without requiring treatment.2

The definitive management of advanced FL remains controversial due to the large number of available treatment options. Clinicians who treat patients with FL must tackle a plethora of problems and choices, such as: (1) there is no standard frontline therapy, (2) there is no standard second-line or subsequent therapy, (3) there are a broad number of efficacious therapeutic options with a wide range of toxicities, and finally, (4) there is no consensus as to the optimal sequence in which to offer these various therapies. Within the scope of this chapter, the options for relapsed and refractory patients will be further discussed because hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has no role in first remission patients. For relapsed patients with limited stage disease (1 or 2 nodal areas) without constitutional symptoms, involved field radiation therapy may suffice, because FL tends to be highly responsive to external beam radiation therapy.3 For FL patients with bulky disease and/or constitutional symptoms, the combination of RTX with chemotherapy with regimens such as R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab), R-FCM (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone), or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) are commonly used treatment options with low to moderate toxicity profiles and can be administered in the outpatient setting.4–7 Bendamustine is an interesting chemotherapeutic agent that has properties of both an alkylator and a purine analog. Bendamustine as a single agent or in combination with RTX represents another efficacious, well-tolerated option.8–9 Phase 2 studies have reported responses with lenalidomide and also with the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib.10–11

Yttrium90 ibritumomab tiuxetan and iodine131 tositumomab represent the 2 anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugates that are FDA-approved for relapsed and refractory FL patients.12–13 The response rates for both agents are comparable, ranging from 60%-80% with responses also seen in RTX-refractory patients. A new generation of mAbs also show promise, including GA-101, a humanized bioengineered type II anti-CD20 Ab; galiximab, an anti-CD80 Ab; and epratuzumab, a humanized anti-CD22 Ab.14–16

HSCT has typically been offered to younger patients later in the course of their disease due to the long natural history of this disease and the higher risk associated with this procedure. However, improved supportive care, more precise donor selection, and allogeneic reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have lowered nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and broadened eligibility.

Auto-HSCT

Consolidation therapy

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) has been explored as part of consolidation therapy in first remission and in the setting of relapsed disease. Three large, randomized trials from Europe have compared the efficacy of auto-HSCT compared with conventional therapy with IFN-α maintenance as consolidation. In 2 of the 3 trials, progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly higher in the HSCT arms, but there was no difference in overall survival (OS) between the HSCT and conventional therapy arms across all 3 trials. Most concerning was the significantly increased incidence of therapy-related malignancies seen in the HSCT arms that negated the advantage conferred by the improved PFS.17–19 (It should be mentioned that accrual to these trials occurred before the availability of RTX.) Subsequently, the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) and Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi (IIL) conducted the first randomized trial in the RTX era comparing auto-HSCT with standard therapy in high-risk FL patients. A total of 136 patients received R-CHOP as frontline therapy and were then randomized to receive additional RTX or high-dose sequential therapy.20 After a median follow-up of 51 months, the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) was 28% versus 61% (P < .001) in favor of the HSCT arm, but no difference seen in OS. A higher incidence of molecular remission was achieved in the HSCT arm compared with the conventional chemotherapy arm (80% vs 44%, respectively), with molecular remission being the strongest predictor of outcome. Patients in the conventional chemotherapy arm who relapsed were crossed over to the HSCT arm, which resulted in a 68% 3-year EFS after a median follow-up of 30 months.

Based on the results of the above 4 trials, auto-HSCT as consolidation therapy in CR1 patients is not recommended routinely. However, because the majority of these data originated from the pre-RTX era, longer follow-up is necessary in patients who received RTX during initial therapy and in the peritransplantation period to truly determine the efficacy in this specific FL patient population.

Relapsed disease

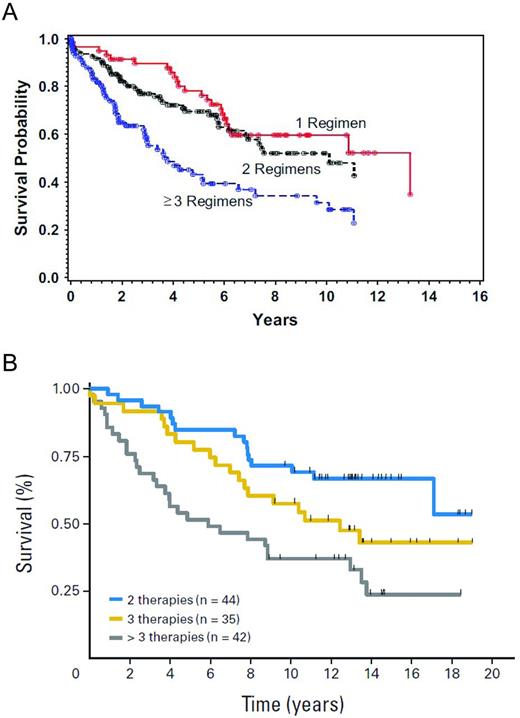

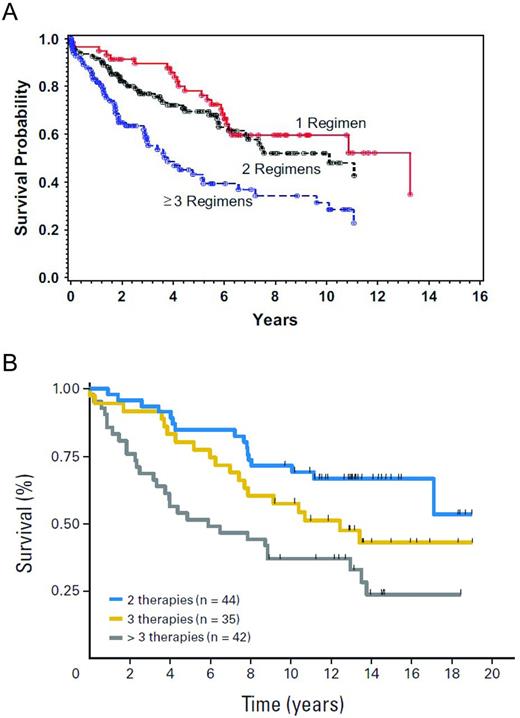

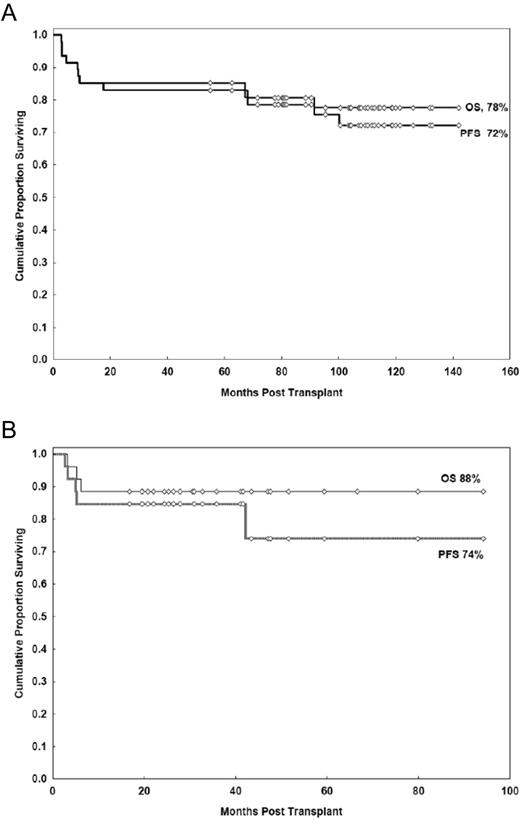

In contrast to patients in first remission, auto-HSCT has a more definitive role in patients with relapsed disease. Both prospective and retrospective studies report high response rates, with 5-year PFS ranging from 40%-50% and one study showing a 10-year PFS of 48%.21–27 With regard to prognostic factors, patients who are not heavily pretreated (ie, those having received less than 3 prior regimens), patients with chemosensitive disease, and those having a lower risk Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score at the time of auto-HSCT had improved OS21,28 (Figure 1A-B). The impact of histological grade on outcome has been examined, but retrospective studies have yielded conflicting results. One study in Seattle showed no effect of having a higher grade of FL (grade 3 vs grades 1-2 FL) at the time of auto-HSCT, whereas a study in Nebraska found that patients with grade 3 FL had inferior outcomes.21,29

OS after auto-HSCT according to the number of prior treatment regimens.21–22 (A) Probability of survival by number of prior treatments. (B) Survival by number of prior treatments.

OS after auto-HSCT according to the number of prior treatment regimens.21–22 (A) Probability of survival by number of prior treatments. (B) Survival by number of prior treatments.

Before the use of RTX, a retrospective series from the European Blood and Marrow Transplant Group (EBMT) reported the outcomes of 693 FL patients who underwent auto-HSCT.25 The 10-year PFS and OS were 31% and 52%, respectively. The relapse incidence was 54%, with relapse occurring at a median of 1.5 years (range, 1 month to 13.5 years) after auto-HSCT. The NRM was 9%. By multivariate analysis, older age, chemoresistant disease and use of a total body irradiation (TBI)–based conditioning regimen correlated with inferior survival. A total of 64 patients (9%) developed a second malignancy at a median of 7 years after HSCT. Another large retrospective series of 241 FL patents who underwent auto-HSCT in Germany and a median follow-up of 8 years26 found a 10-year OS and PFS of 75% and 49%, respectively, with a relapse incidence of 47%. The median time to relapse was 20 months (range, 2-128). Five patients developed a therapy-related malignancy. The EBMT also conducted the CUP (chemotherapy vs unpurged arm vs purged arm) trial, which is the only randomized study that addressed prospectively the role of autologous HSCT compared with standard therapy in relapsed FL patients.23 A total of 140 FL patients with chemosensitive disease after salvage chemotherapy were randomized to receive further conventional therapy, auto-HSCT with a purged graft, or auto-HSCT with an unpurged graft. There was a significant reduction in hazard rates for both PFS and OS between the chemotherapy-only patients and the combined groups of autologous HSCT patients. The 4-year OS was 46% for the chemotherapy arm, 71% for the unpurged arm, and 77% for the purged arm. The sample sizes in the 2 HSCT arms were too small to measure the effect of ex vivo purging. Unfortunately, this trial closed early due to slow accrual and was also conducted in the pre-RTX era, which limits the relevance of the findings.

The Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte/Groupe Ouest Est d'Etude des Leucémies et Autres Maladies du Sang (GELA/GOELAMS) examined retrospectively the impact of auto-HSCT compared with conventional salvage in 175 FL patients at first relapse.27 Forty percent of patients had prior RTX exposure and 40 patients (25%) underwent auto-HSCT. With a median follow-up of 31 months, the 3-year OS was significantly higher in patients who proceeded to HSCT compared with patients who did not undergo HSCT (92% vs 63%, respectively; P = .0003). Frontline RTX exposure did not affect outcome. Because this was a retrospective study, the favorable impact of HSCT may have been affected by selection bias, because only patients responding to salvage therapy proceeded to HSCT.

Based on the current literature, it is easier to determine who is not an ideal patient for auto-HSCT rather than ascertain who is the optimal candidate. Relapsed FL patients who should not be offered auto-HSCT include those who are chemoresistant, had 3 or greater prior regimens, have a poor performance status, and those greater than 70 years of age. Otherwise, patients who are beyond CR1 but chemosensitive, do not have BM involvement, and have a good performance status are excellent candidates for auto-HSCT. However, for patients with limited stage at relapse, thoughtful consideration should include offering only radiotherapy and/or conventional treatment. Naturally, the next question is: when should allo-HSCT be offered instead of auto-HSCT? This perpetually challenging question will be addressed later in this chapter.

Graft purging

With the goal of eliminating autograft contamination and increasing the probability of obtaining a molecular remission after HSCT, both in vitro and, more recently, in vivo methods of graft purging have been explored. Early studies that involved autologous BM purged in vitro with mAbs and complement showed that patients who received PCR− grafts had significantly longer PFS compared with patients who received PCR+ grafts.24 In an Italian study of 92 FL patients, PCR− peripheral blood autografts could also be obtained if patients received intensive salvage followed by a moderately high dose of mobilization chemotherapy just before leukapheresis. As observed in the studies of purged BM grafts, PFS was significantly longer in the patients who received a PCR− graft. In addition, achievement of molecular remission after HSCT was predictive of improved PFS compared with patients who never achieved a molecular remission.

When RTX became available, in vivo purging largely replaced in vitro graft purging procedures. Preliminary studies consistently demonstrated that PCR− peripheral blood autografts could be obtained when RTX was incorporated into chemomobilization regimens.30–31 An early trial included 36 FL patients with relapsed/refractory disease who received intensive RTX-based salvage chemotherapy and mobilization chemotherapy. A PCR− graft was collected in 97% of patients and after long-term follow-up, the median OS and PFS were not reached. The 12-year OS and PFS were 70% and 76%, respectively, with a plateau observed at 6 years.32 In a prospective trial from Italy, 61 relapsed FL patients received RTX-based salvage therapy and mobilization chemotherapy.33 After auto-HSCT with the in vivo purged graft, 2 more doses of RTX were given as consolidation thereapy. In patients informative for the bcl-2 rearrangement, molecular response was defined as the absence of this rearrangement in the BM. The peripheral blood autografts were considered free of lymphoma if PCR− for the bcl-2 rearrangement. PCR− harvests were collected in all of the 33 PCR-informative patients. The 5-year PFS was 59%. Patients who achieved negativity for the bcl-2 rearrangement after HSCT experienced a longer PFS compared with patients who became bcl-2 positive, further underscoring the importance of achieving and maintaining a molecular remission.

With the advent of RTX, in vivo graft purging has become the purging method of choice. This method of purging is technically easier and less labor intensive compared with in vitro methods, which are no longer used commonly. In light of the data showing that RTX can render PCR− autografts and that achievement of molecular remission after auto-HSCT is a strong predictor of prolonged clinical remission, in vivo graft purging with RTX is recommended.

RTX maintenance after auto-HSCT

In randomized trials, maintenance RTX (MR) therapy after conventional salvage therapy improved PFS and OS in FL patients with relapsed disease.34 There is also evidence that relapsed FL patients may benefit from MR after auto-HSCT. A large randomized study from the EBMT showed significantly higher PFS in patients who received MR after auto-HSCT at a dose of 375 mg/m2 every 3 months for 2 years compared with patients who did not receive MR.35 Before this randomized trial, phase 2 trials administering MR after auto-HSCT demonstrated the feasibility and safety of MR after auto-HSCT and showed that MR could eradicate minimal residual disease persisting after auto-HSCT. Adverse events associated with MR in this setting include prolonged hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, and leukopenia36,37 Therefore, there are data showing that MR prolongs PFS after auto-HSCT for patients with relapsed FL; however, it is not yet clear if OS is improved.

Conditioning regimens

The most frequently used conditioning regimens for FL patients undergoing auto-HSCT include BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan), BEAC (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide), and CBV cyclophosphamide, carmustine, etoposide). TBI-based regimens such as TBI plus cyclophosphamide and/or etoposide are also offered, but less so because several retrospective studies have linked the use of TBI with a significantly higher risk of developing therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after auto-HSCT.25,38–39 The cumulative incidence of developing therapy-related MDS/AML after auto-HSCT ranges from 4%-20%, as reported in the literature, and occurs at a median of 2.5-7 years after auto-HSCT.

The anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugates, yttrium90 ibritumomab tiuxetan and iodine131 tositumomab have been used as single agents or combined with high-dose chemotherapy as conditioning regimens before auto-HSCT.40–42 Data reported so far demonstrate that such regimens are well tolerated and adverse effects are comparable to chemotherapy-only regimens. However, these agents are currently not routinely offered with auto-HSCT in light of their high cost and the complex logistical steps needed to administer such agents. In addition, regimens containing radioimmunoconjugates do not appear to increase efficacy compared with chemotherapy-alone regimens. Based on the current data, chemotherapy-only conditioning regimens are favored. Other conditioning regimens should only be offered within the context of a clinical trial.

Allo-HSCT

Allo-HSCT is the only known curative modality for patients with FL. The existence of a GVL effect mediated by donor T cells is supported by the observation of lower relapse rates compared with autologous HSCT for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients. The strength of the GVL effect varies widely among lymphoma histologies, with indolent histologies such as FL being the most sensitive to the GVL effect and the high-grade lymphomas being the least sensitive.43 In addition, for patients with indolent lymphoma who relapse after allo-HSCT, disease regression has been reported after withdrawal of immunosuppression medications and after donor leukocyte infusions.44–46

In the earlier studies of allo-HSCT for FL patients, myeloablative regimens were primarily offered and yielded lower relapse rates compared with recipients of auto-HSCT.47–49 Plateaus in relapse incidence were noted after 2-5 years after allo-HSCT, whereas a continuous pattern of relapse occurred in the auto-HSCT patents. However, the high NRM associated with the ablative regimens mitigated the benefit of a lower relapse risk. Two large registry studies from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and the EBMT compared the outcomes of relapsed FL patients who underwent either auto-HSCT or myeloablative allo-HSCT.47,50 In both studies, the relapse risk was significantly lower in the allo-HSCT group compared with the auto-HSCT recipients, but the treatment-related mortality (TRM) ranged from 30%-38%. Therefore, OS was comparable between the auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT recipients, because the significantly higher TRM in the allo-HSCT group offset any advantage conferred by the lower relapse risk. In both studies, the long-term OS for both the auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT groups ranged from 50%-62%. Three single-institution retrospective analyses with myeloablative regimens have reported durable remissions in FL patients, with 5-year EFS ranging from 45%-75% and outcomes dependent on chemosensitivity at the time of allo-HSCT.51–53 The study from Toronto reported a TRM of 15%, which is notably lower than the other series.52 This notable low TRM could be because all patients in the Toronto series were chemosensitive, whereas the other 2 studies included resistant and refractory patients. In addition, 4 patients (10%) in the Toronto group underwent syngeneic HSCT, which eliminates the risk of TRM related to GVHD.

RIC allo-HSCT

Allo-HSCT that incorporates RIC regimens rely more on the donor-mediated GVL effect rather than the cytoreduction of high-dose chemotherapy. The goal of RIC regimens is to confer adequate immunosuppression of the recipient to facilitate engraftment with a minimal to moderate amount of cytoreduction. RIC allo-HSCT has been used increasingly in FL patients and results have shown durable remissions and less NRM compared with myeloablative regimens. With the advent of RIC regimens, patient eligibility has expanded significantly and includes patients greater than 70 years of age, patients who had failed a prior auto-HSCT, and patients with comorbid conditions who otherwise would not be eligible to safely receive an ablative regimen.

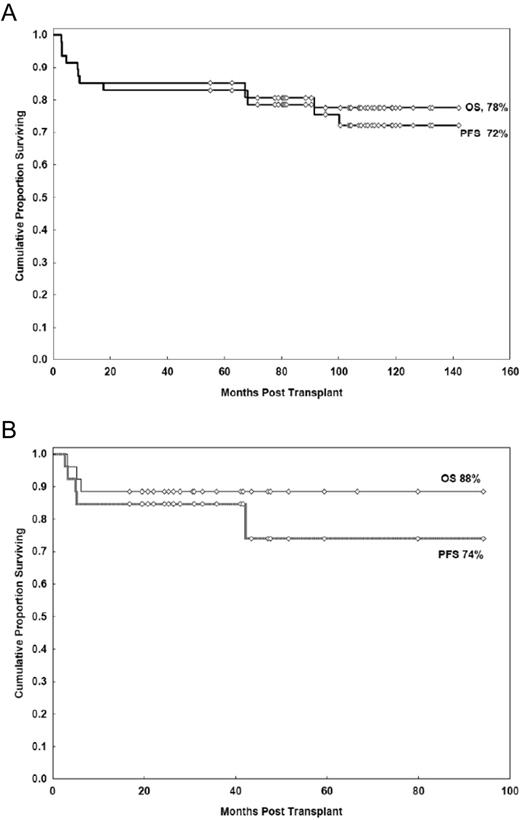

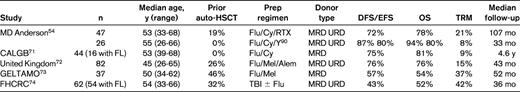

Table 1 provides outcomes on 5 selected prospective trials of FL patients undergoing RIC allo-HSCT. Four of the 5 trials included patients who had failed a prior auto-HSCT. All 5 trials included patients above 60 years of age and used a fludarabine-based preparative regimen. With median follow-up ranging from 3-10 years, the disease-free survival/EFS ranged from 43%-75% and OS ranged from 52%-81%. Chemosensitivity at the time of HSCT was a consistent predictor of outcome. The trial from the M.D. Anderson group represents the prospective trial with the longest follow-up of 107 months.54 Forty-seven patients with relapsed FL received the FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and RTX) regimen that incorporated a high dose of RTX in which 3 of the 4 planned doses were given at a dose of 1000 mg/m2. High-dose RTX results in prolonged serum concentrations, which facilitates cytoreduction and may augment the GVL effect through Ab-dependent cellular toxicity.55 RTX also may confer a protective effect against acute GVHD via profound B-cell depletion.56 The 11-year EFS and OS in that study were 72% and 78%, respectively, with only 3 relapses observed (Figure 2A). Based on these impressive results, the BMT CTN (Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network) is conducting a phase 2 multicenter trial using the same FCR regimen in relapsed FL patients with chemosensitive disease who have either a matched related or a matched unrelated donor identified. It is anticipated that accrual will be completed at the end of 2012.

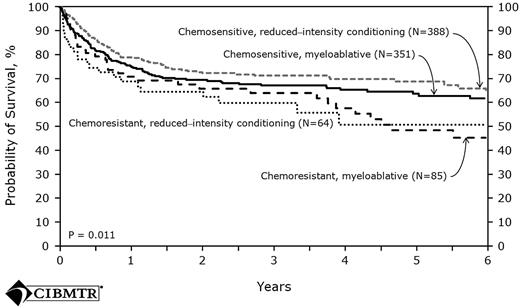

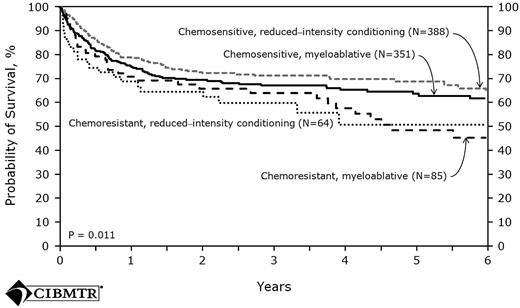

The largest prospective series comes from the United Kingdom and used a preparative regimen with in vivo T-cell depletion. A total of 82 patients received fludarabine, melphalan, and alemtuzumab with cyclosporine alone as posttransplantation immunosuppression. The incidence of grades 2-3 acute GVHD was 13% and the 4-year cumulative incidence of extensive chronic GVHD was only 18%. The relapse risk was 26%, which was higher compared with the relapse seen in non–T-cell-depleted trials. However, this relapse risk was later reduced when donor lymphocyte infusion was given to patients who had mixed chimerism for conversion to full donor chimerism and to patients who had relapsed after HSCT. These interventions resulted in a 4-year PFS of 76% for the entire cohort. With the specific goal of assessing the effect of in vivo T-cell depletion in FL patients undergoing RIC allo-HSCT, the EBMT examined retrospectively the outcomes of 164 patients who had matched sibling donors. For the analyses, patients were divided into 3 groups: the first (n = 46) received ATG as part of the preparative regimen, the second group received alemtuzumab (n = 42), and the third group (n = 76) received neither agent. Although the patients in the T-cell depletion (TCD) group experienced significantly lower incidences of acute and chronic GVHD compared with the non-TCD recipients. There was no observed difference in NRM between the TCD and non-TCD groups; however, the use of a TCD was a risk factor for a significantly higher relapse rate (28% vs 14%, P = .05). The strongest predictor of all outcomes (PFS, OS, relapse, and NRM) was disease status at transplantation. Recent data from the CIBMTR further demonstrated that chemosensitivity, rather than intensity of the conditioning regimen, was a strong determinant of outcome57 (Figure 3).

Probability of survival after HLA-matched sibling donor allo-HSCT for FL 1998-2007 by disease status and conditioning regimen.57

Probability of survival after HLA-matched sibling donor allo-HSCT for FL 1998-2007 by disease status and conditioning regimen.57

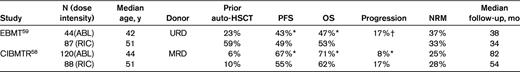

Two large registry studies compared directly the outcomes of FL patients who underwent either myeloablative or a RIC allo-HSCT. In both studies, the RIC recipients were significantly older and a higher number had failed a prior auto-HSCT compared with the ablative recipients (Table 2). The CIBMTR analyses was limited to recipients with matched related donors and found no difference in PFS and OS based on conditioning regimen.58 However, the risk of progression was significantly higher in the RIC group. The EBMT study had patients with solely unrelated donor grafts.59 In contrast to the CIBMTR study, recipients of the RIC regimens had a lower NRM and experienced a significantly improved PFS and OS by multivariate analysis, and relapse was comparable between the 2 groups. Therefore, it was suggested that the GVL effect may be more robust from an unrelated donor graft. In both the CIBMTR and EBMT studies, chemoresistance and a lower performance status were found to affect TRM, OS, and PFS adversely.

Based on the results of these studies, when allo-HSCT is indicated, when should the clinician recommend an ablative regimen versus an RIC regimen? Because evidence in both retrospective and prospective trials has revealed that chemosensitivity rather than conditioning intensity is the most reliable predictor of outcome, the absolute indications for an ablative regimen are nearly obsolete. Therefore, a myeloablative regimen should not be recommended for an FL patient outside of a clinical trial.

Novel conditioning regimens

The success of RIC allo-HSCT represents remarkable progress in the treatment and cure of patients advanced FL. Patients with chemosensitive disease at the time of HSCT benefit the most from these regimens; for patients with chemorefractory disease, the options are much more limited. Therefore, strategies to increase the anti-lymphoma activity without increasing toxicity have been examined, most prominently the use of radioimmunotherapy. Radioimmunotherapy confers cytoreduction via targeted delivery of radiation with isotopes conjugated to mAbs. This method has shown efficacy in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas, including in patients who are refractory to RTX and combination chemotherapy.60 The M.D. Anderson group recently published the results of a prospective trial of RIC allo-HSCT using the novel YFC (90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) regimen54 (Figure 2B). Twenty-six patients with advanced FL, including 10 patients who were chemorefractory, participated. With a median follow-up of 33 months, the 3-year PFS for the chemorefractory and chemosensitive patients were 80% and 87%, respectively. The 1-year TRM was 8%. In another prospective study, a German group used an RIC regimen comprised of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan, fludarabine, and low-dose TBI in 40 patients with advanced NHL, including 17 patients with FL.61 All patients were high risk as defined by refractory disease or relapse after prior auto-HSCT. The 2-year OS and EFS for the FL patients were 67% and 57%, respectively. However, the 2-year NRM was 45% for all patients, with infection being the leading cause of death. The high NRM was attributed to the age of the patients (median, 56 years), advanced-stage disease, and the predominant use of unrelated donors. There was a trend for a decreased rate of NRM if a related versus an unrelated donor was used (16% vs 58%, respectively, P = .07). A small, retrospective study from the Dana Farber Cancer Institute used a conditioning regimen of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan, fludarabine, and low-dose busulfan.62 This study involved 12 FL patients, including 5 patients with refractory disease and 2 patients with transformed disease. The 2-year OS, PFS, and NRM were 83%, 74%, and 18%, respectively. Based on the results of these 3 studies, the incorporation of radioimmunotherapy in RIC allo-HSCT regimens is feasible because of the acceptable rates of NRM and shows promising efficacy in patients with chemorefractory disease.

Tandem auto-HSCT followed by allo-HSCT

The use of tandem auto-HSCT followed by RIC allo-HSCT reported recently by a Canadian group represents the first study offering tandem auto-HSCT/allo-HSCT specifically for FL patients.63 Twenty-seven patients were enrolled, including patients with chemorefractory and transformed disease. Despite this high-risk population, the 3-year PFS and OS were both 96%, with only 1 death attributed to NRM. A retrospective Italian series reported the results of 34 high-risk NHL patients, including 14 patients with FL, who underwent tandem auto-HSCT followed by RIC allo-HSCT.64 With a median follow-up of 4 years, the 5-year OS and PFS were 77% and 68%, respectively, with a 2-year TRM of 6%. These results suggest that the intense cytoreduction conferred by the high-dose chemotherapy with auto-HSCT followed by eradication of minimal residual disease via RIC allo-HSCT may overcome the negative prognostic outcome associated with chemoresistance. The low TRM seen in both studies is especially encouraging.

Therapy-related malignancies after HSCT

Although therapy-related malignancies are rare events after HSCT, all patients should be advised of the risks and counseled regarding screening for such complications in the long term. The incidence of these malignancies, including therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (t-MNs) and solid tumors in NHL patients after auto-HSCT ranges from 5%-20%.17–19,25–26,65 Risk factors associated with developing t-MNs, such as t-MDS and t-AML, include receipt of prior alkylator agents, fludarabine, older age at the time of HSCT, TBI-based preparative regimens (especially in doses greater than 1320 cGy), and receipt of an in vitro purged autograft.19,39,66 Use of a TBI-based regimen before auto-HSCT was associated with a disturbing 4-fold risk of developing t-MNs in a retrospective EBMT study of FL patients.25 The risk of t-MNs is reported more often after auto-HSCT compared with allo-HSCT and is attributed to the exposure of autologous stem cells to prior chemotherapy and the ensuing DNA damage. The risk of developing solid tumors after HSCT has also been reported, although it is described more often after allo-HSCT than auto-HSCT. The group from Dana Farber Cancer Institute reported a 10-year incidence of solid tumors of 10% after auto-HSCT in patients with NHL who received a TBI-based preparative regimen.65

Recipients of allo-HSCT are at risk for secondary solid tumors and posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. After allo-HSCT, the cumulative risk of developing a solid tumor ranges from 2%-6%, with the risk increasing over time and reaching up to a 3-fold risk in patients followed over 15 years after allo-HSCT. The strongest risk factors for the development of solid tumors are the use of TBI and chronic GVHD. TBI exposure is associated with nonsquamous cell cancers, especially breast, thyroid, bone, brain cancers and malignant melanoma, and also increases the risk of basal cell skin cancer. The development of squamous cell cancers of the skin and mucosal surfaces increases with the presence of chronic GVHD.67–68

After HSCT, patients should be strongly encouraged to adhere to cancer screening guidelines for the general population for skin, cervical, breast, and colon cancers. For female patients who received TBI or chest irradiation, annual mammograms should be commenced at the age of 25 years or 8 years after irradiation, whichever occurs later. Patients with chronic GVHD should be especially vigilant in limiting sun exposure, maintaining good oral hygiene, and having regular dental examinations that include screening for oral cancers.69

Summary/recommendations

First remission

With the exception of patients in first remission, the optimal timing and the optimal conditioning regimen in patients with FL undergoing HSCT remains controversial. The mature results of 3 large, randomized studies show no benefit of auto-HSCT as consolidation therapy for patients in first complete remission.

Relapsed disease

Patients with relapsed FL should be directed to HSCT before they are considered “heavily pretreated.” Two studies have demonstrated that outcomes are more favorable if patients have received less than 3 prior regimens.21,70 For patients who are allo-HSCT candidates, chemosensitivity is the most robust prognostic factor for survival after HSCT regardless of conditioning intensity.58 Based on current data, the relapse rate is unequivocally lower with allo-HSCT compared with auto-HSCT. Fortunately, the NRM associated with allo-HSCT has declined with the use of RIC regimens, and clear plateaus in survival and relapse are now observed frequently after RIC allo-HSCT.

If a patient has chemosensitive disease and has a suitably identified donor, should he or she be directed toward an auto-HSCT or an allo-HSCT? In our center, with a patient who is past first remission and demonstrates chemosensitive disease, we favor proceeding to RIC allo-HSCT if a suitable donor (matched related or matched unrelated donor) can be found in a timely manner. However, one could rationalize offering a patient auto-HSCT initially, because auto-HSCT clearly extends PFS and a growing body of evidence suggest that auto-HSCT may be curative. RIC allo-HSCT would be reserved for the situation in which a patient relapsed after auto-HSCT, because prospective trials have shown that RIC allo-HSCT can salvage patients who failed a prior auto-HSCT. The obvious advantages of this approach are the low NRM inherent with auto-HSCT and the more expedient recovery. The main disadvantage is that subsequent relapsed disease may not respond to further salvage therapy, which greatly diminishes the potential efficacy of RIC allo-HSCT. However, if a patient has compromised cardiac or pulmonary function, then high-dose chemotherapy may not be feasible and RIC allo-HSCT should be offered. Treatment choices must be individualized based on concurrent comorbidities, age, performance status, donor availability, psychosocial issues, and, very importantly, caregiver availability.

Refractory disease

It is controversial whether patients with chemorefractory disease are HSCT candidates, and such patients should only be offered HSCT within a clinical trial. Auto-HSCT is not recommended for chemorefractory patients, but allo-HSCT may have a role in the setting of tandem HSCT (auto-HSCT followed by allo-HSCT) or with the incorporation of radioimmunoconjugates or other novel agents.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Ginna G. Laport, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Stanford University Medical Center, 300 Pasteur Dr, Rm H0101, Stanford, CA 94305-5623; Phone: 650-723-0822; Fax: 650-725-8950; e-mail: glaport@stanford.edu.