Abstract

Despite promising advances leading to improved survival, many patients with hematologic malignancies end up dying from their underlying disease. Their end-of-life (EOL) care experience is often marked by worsening symptoms, late conversations about patient values, increased healthcare utilization, and infrequent involvement of palliative care and hospice services. There are several challenges to the delivery of high-quality EOL care that span across disease, patient, clinician, and system levels. These barriers include an unpredictable prognosis, the patient's prognostic misunderstandings and preference to focus on the immediate future, and the oncologist's hesitancy to initiate EOL conversations. Additionally, many patients with hematologic malignancies have increasing transfusion requirements at the end of life. The hospice model often does not support ongoing blood transfusions for patients, creating an additional and substantial hurdle to hospice utilization. Ultimately, patients who are transfusion-dependent and elect to enroll in hospice do so often within a limited time frame to benefit from hospice services. Strategies to overcome challenges in EOL care include encouraging repeated patient-clinician conversations that set expectations and incorporate the patient's goals and preferences and promoting multidisciplinary team collaboration in patient care. Ultimately, policy-level changes are required to improve EOL care for patients who are transfusion-dependent. Many research efforts to improve the care of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of life are underway, including studies directed toward patients dependent on transfusions.

Learning Objectives

Recognize barriers in implementing timely end-of life-care for patients with transfusion-dependent hematologic malignancies

Identify strategies to facilitate end-of-life care for patients with transfusion-dependent hematologic malignancies

CLINICAL CASE

Mrs. S is a 75-year-old woman with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) initially on venetoclax and azacitidine. She achieved completion remission after one cycle but was hospitalized due to sepsis, dehydration, and fatigue. Venetoclax was discontinued, and she has been on azacitidine alone since then. One year later, she has worsening cytopenias requiring weekly red blood cell transfusions. Her repeat bone marrow biopsy confirms progressive AML without any actionable mutations. You meet with Mrs. S and her husband to discuss her care. She tells you that she does not want to pursue any further cancer-directed treatments but does want to continue receiving transfusions because they give her enough energy to knit for her granddaughter. She is afraid of dying in an unfamiliar place like the hospital.

Introduction

Despite promising advances leading to improved survival across hematologic malignancies, many patients ultimately die from their disease. Key elements of achieving quality end-of-life (EOL) care include early goals of care (GOC) discussions and palliative care integration, avoidance of intensive healthcare utilization near the end of life, and appropriate hospice use.1 Patients with hematologic malignancies and their families appreciate early GOC discussions in order to help plan for the future and avoid suffering at the end of life.2 In particular, GOC discussions that facilitate patients' weighing of their values and preferences are associated with improved healthcare utilization near death, including fewer intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and increased hospice use.3,4 Aggressive medical care, in turn, is associated with worse patient quality of life (QOL) and caregiver bereavement.5 Meanwhile, palliative care integration starting early in the course of a patient's illness helps facilitate improvements in not only EOL care but also QOL and psychological outcomes.6

Unique circumstances of hematologic malignancies create challenges to optimal EOL care and achievement of a good death. Many patients like Mrs. S who are ready to forgo further cancer-directed treatments are transfusion-dependent and benefit symptomatically from transfusions. Indeed, transfusions even in advanced disease help to manage symptoms such as bleeding, breathlessness, and fatigue and have a positive impact on QOL.7 Nonetheless, transfusion dependence adds complexity and challenges in the provision of optimal and timely EOL care.

In this review, we discuss the current state of EOL care in hematologic malignancies, barriers to accessing palliative care and hospice, and potential strategies to overcome these barriers.

Current state of end-of-life care and hospice in hematologic malignancies

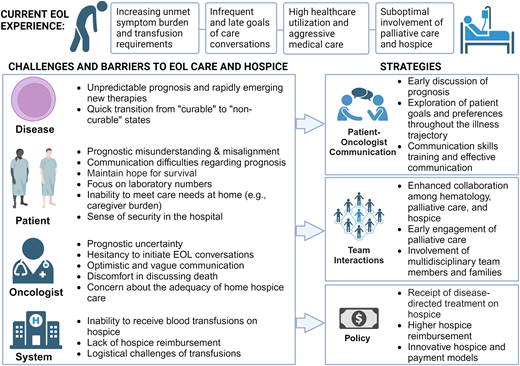

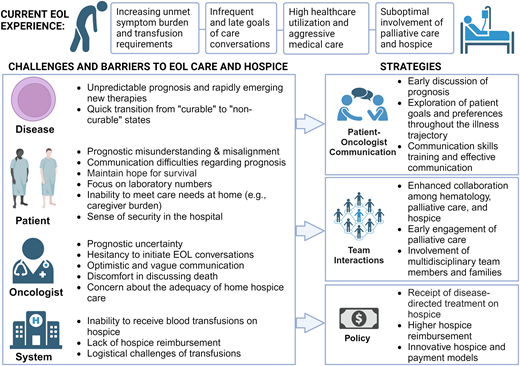

The current state faced by patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of life is suboptimal (Figure 1). In the final six months of life, patients suffer from worsening symptoms including fatigue and breathlessness, as well as diminished QOL and psychological health.8,9 Such unmet physical and existential burdens highlight a need to optimize early palliative care involvement.8,9 Many patients also have escalating transfusion requirements; patients with AML require a median of 16 red blood cell (RBC) and 12 platelet transfusions in the last 6 months of life and approximately 5 RBC and 5 platelet transfusions in the final month alone.9 Between 31% and 70% of patients with advanced illnesses report subjective improvement after transfusion.7,10

Current experience of patients with blood cancers at the end of life.

Meanwhile, communication about patients' goals and end of life is neither timely nor consistent. Two-thirds of first documented GOC conversations occur while patients are hospitalized,3 and nearly a quarter of hematologists report waiting until shortly before death to bring up hospice for the first time.11 Over a third of patients never have a documented GOC conversation.3

In addition, patients with hematologic malignancies have high healthcare utilization at the end of life, with rates significantly higher than those reported in patients with metastatic solid tumors.12 In particular, rates of hospital admission for patients with AML are as high as 85% to 92% and 67% in the final month and week of life, respectively.9,13,14 Meanwhile, 22% to 39% of patients with hematologic malignancies require ICU-level care in the final month of life, and 13% to 21% receive chemotherapy in the final 14 days of life.3,12,15,16

Finally, many patients with hematologic malignancies die in a location not consistent with their wishes. Although patients' preferences regarding the place of death can fluctuate over their illness course, many maintain a strong preference for dying at home.2,4 However, only half of those who prefer dying at home do so, and patients who are hospitalized a week before death have only a 20% chance of leaving the hospital before death.4,17 Overall, 33% to 58% of patients with hematologic malignancies die away from home, with the highest rate of hospital death (approximately 60%) observed in older patients with AML.3,4,13-15 Importantly, patients who have high transfusion burdens have a higher chance of in-hospital death compared to those who do not.9

Palliative care and hospice in hematologic malignancies

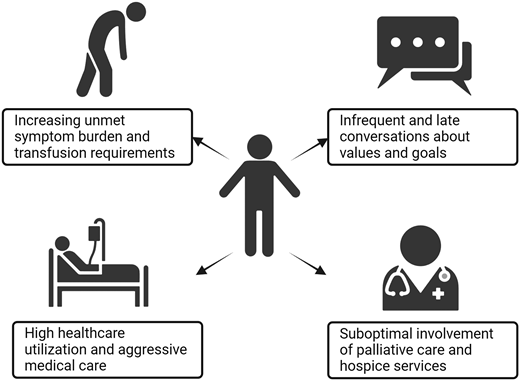

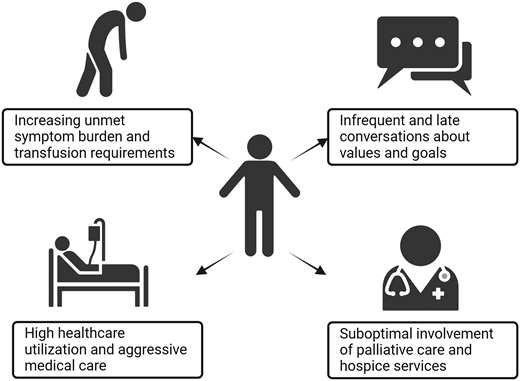

Palliative care promotes quality care across patients' illness experiences from diagnosis to death, through managing pain and symptoms, engaging in big-picture discussions with patients and their families, supporting caregivers, and providing expert EOL care (Figure 2). Early integration of specialty palliative care leads to improved QOL and psychological distress and less aggressive EOL care.6

Hospice incorporates many of the core principles of palliative care and is available for patients whose life expectancy is 6 months or less if the terminal illness runs its normal course. Hospice focuses on addressing patients' symptoms to optimize QOL and comfort at the end of life instead of pursuing life-prolonging therapy targeting their terminal condition. Under the Medicare Hospice Benefit, everything deemed related to a patient's terminal illness is paid for under the hospice plan of care. Table 1 outlines the framework under Medicare and Medicaid services that support hospice eligibility for patients with cancer.18Figure 2 shows the composition of a hospice care team. Regardless of transfusion-dependence status, patients with hematologic malignancies who use hospice services have more favorable outcomes, including less chemotherapy use near death, fewer hospital deaths, and lower overall Medicare spending.15,19

Historically, palliative care teams have not been invited to participate regularly in the care of patients with hematologic malignancies. While palliative care involvement has increased over time, only up to 16% of the most seriously ill subpopulations of patients with hematologic malignancies receive palliative care services.13 When palliative care is involved, the timing of initial consultation is most commonly less than 2 weeks before death.12,13

Similarly, patients with hematologic malignancies do not regularly enroll in hospice, and those who do frequently have too short a stay to derive maximal benefit. While rates of hospice enrollment have increased over time, they remain below national averages for solid tumors and other serious illnesses.20 The rate is generally lowest for patients with AML (23% to 41%) and higher among patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (42%), myelodysplastic syndromes (49%), and multiple myeloma (57%).9,13,14,16,21,22 Patients with hematologic malignancies who enroll in hospice have an estimated length of stay of 9 days, well below the 2021 national average of 17 days.15,23 Further, over a quarter of patients with AML who enroll do so within the final 3 days of life.24

Patients who are transfusion-dependent are even less able to benefit fully from hospice services. Although patients who are transfusion-dependent are slightly more likely to enroll in hospice, their length of stay is half that of those who are transfusion-independent (6 vs 11 days).19 This pattern was seen across both acute and chronic hematologic malignancies, implying that rapid clinical decline was not the reason for this difference. This suggests that patients who are transfusion-dependent are unable to benefit fully from hospice services despite having great need.19

Challenges and barriers with EOL care and hospice

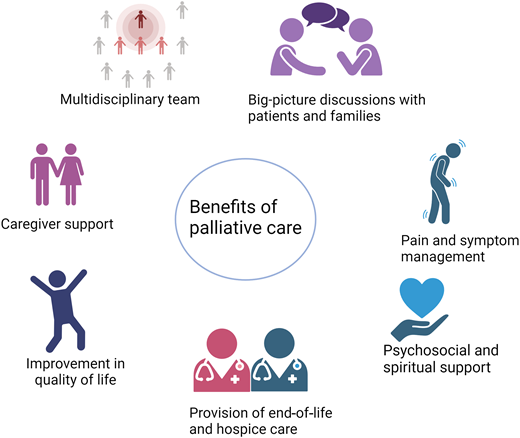

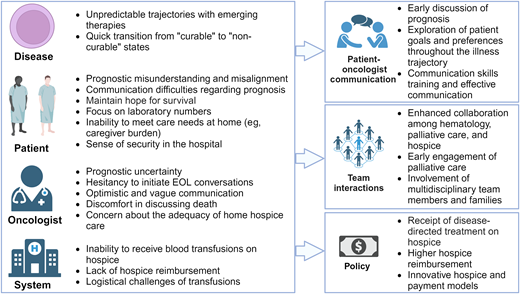

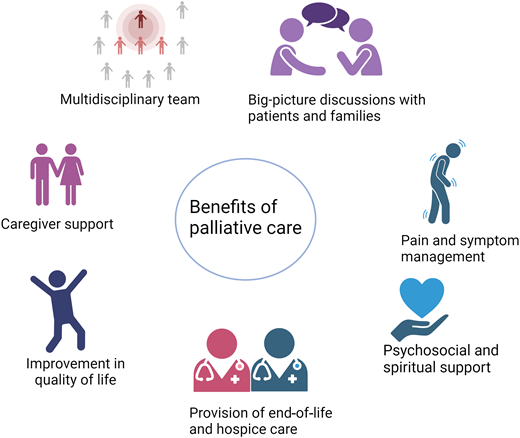

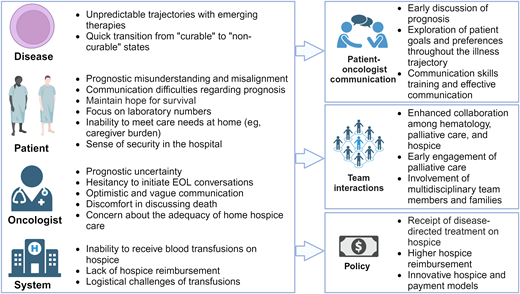

Delivering high-quality EOL care and hospice services presents numerous challenges, spanning disease levels, the patient, the clinician, and the system (Figure 3). At the disease level, hematologic malignancies are rife with prognostic uncertainty, and emerging therapies lead to even greater unpredictability in prognosis and challenges in symptom management. Novel treatments may offer prospects of extended survival for some patients, even those unable to endure intensive regimens or who have undergone multiple prior treatment lines. For example, Mrs. S and others with AML may achieve complete remission on azacitidine and venetoclax, potentially leading to long-term survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (although Mrs. S chose not to given initial chemotherapy-associated complications). However, not all patients will achieve a meaningful extension of life with novel treatments. Further, in lymphomas, while over half of patients with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who undergo cellular therapies survive beyond 5 years, outcomes drastically decline for those who no longer respond to chimeric antigen receptor therapy.25 These scenarios underscore the unpredictable prognosis of hematologic malignancies, where transitions from “curable” to “non-curable” states pose significant challenges in discussing the terminal illness trajectory and recommending appropriate EOL care options. In addition, novel therapies have unique and potentially burdensome side effects, including prolonged severe cytopenias leading to increased transfusion requirements and symptoms, which can further complicate EOL care.

Challenges and barriers to end-of-life care and hospice with associated strategies to overcome these barriers.

Challenges and barriers to end-of-life care and hospice with associated strategies to overcome these barriers.

At the patient level, several studies have demonstrated prognostic misunderstanding or misalignment among patients with hematologic malignancies, a challenge commonly recognized by clinicians and hospice agencies.26-28 This misalignment persists even after patients discuss their illnesses with their clinicians.26 Such misunderstandings may arise from communication difficulties regarding the prognosis or from patients' need to maintain hope and cope with their illness. Many patients prefer to focus on the present and may not feel prepared to contemplate the future, even when the prognosis is poor.29 Moreover, patients often rely on laboratory numbers and may become distressed by the risk of bleeding, leading them to opt for transfusions even when they do not observe symptomatic benefits.28,30 The often rapid transition to end of life can make patient care needs at home more challenging and add to the caregiver's burden. Some patients and caregivers also may feel a sense of safety and security offered by hospital settings, making EOL care in the hospital more appealing.1,4

At the clinician level, long-standing patient-clinician relationships and potential philosophical concerns about palliative care compel many oncologists to retain primary ownership as their patients approach the end of life.30,31 However, prognostication is challenging, particularly in the setting of rapidly developing and increasingly efficacious therapies.32 Given the potential for long-term survival for some patients undergoing novel therapies, oncologists may find it difficult to determine when to transition from life-prolonging therapy to comfort-focused care and may hesitate to initiate EOL conversations.30,33 In addition, they often find discussions about death, dying, and hospice uncomfortable or view them as taboo subjects.30,34 These factors can lead to optimistic and vague communication with patients and prognostic misunderstanding.30,34 Some oncologists also are concerned about whether home hospice care can adequately meet individual needs, particularly for patients who require transfusion support.35

At the system level, some of the most significant barriers to accessing hospice care in hematologic malignancies arise from philosophical, financial, and logistical constraints. Hospice generally requires patients to forgo treatments directed at their underlying life-limiting disease, often including the discontinuation of blood transfusions.27,30,35 However, transfusions are infrequently offered based on a survey of hospice providers (55% never offered, 41% sometimes offered, and 3% always offered transfusions).28 Nonetheless, patients consistently emphasize the importance of access to blood transfusions in their decision-making process regarding hospice care.36 In fact, when patients disenroll from hospice, they are more likely to do so because they would like to receive transfusion support.28 Compounding this issue, hospice services are reimbursed at a fixed daily rate, which is intended to cover the cost of all clinical services, personal care assistance, medications, and equipment in the home in order to meet the needs of the patient and family. For instance, the daily payment rate for routine home hospice care in 2023 averaged $211, significantly less than the cost of a single blood transfusion (RBC transfusion has a median charge of $634).37 This financial misalignment is exacerbated by the growing presence of for-profit hospice agencies that may prioritize cost containment over comprehensive patient care.28 Additionally, the blood transfusion process itself, even outside of hospice, is logistically challenging. The time and effort patients spend in transportation, waiting rooms, clinics, and infusion centers can become increasingly burdensome, particularly as their clinical status worsens. Home transfusions are not currently accessible to the vast majority of patients.

Potential strategies to overcome barriers with EOL care and hospice

Multilevel strategies can address the barriers to achieving optimal EOL care and timely hospice enrollment. Oncologists can promote opportunities to discuss prognosis, ideally after establishing a strong patient-clinician relationship and trust.38 Continuous exploration of patient goals and preferences is necessary throughout the illness trajectory, as patient preferences often evolve over time.1,4,30 Effective communication techniques that provide structure, clarity, and support and set realistic expectations can help patients and their families to navigate available treatment pathways and make informed decisions. Such techniques include assisting patients in ranking their priorities related to cancer treatment and discussing prognosis in terms of both best case and worst case.39,40 Oncologists can also benefit from communication skills training that is tailored to their patients' needs.1

In parallel, enhanced collaboration among oncology, palliative care, and hospice clinicians is imperative.1,28,31 Palliative care's focus on coping and big-picture decision-making and planning throughout the course of a patient's illness can complement oncologic care and help with the transition to hospice when appropriate.41 Furthermore, actively involved multidisciplinary team members may offer valuable insights into local hospice availabilities and capabilities, which can vary among hospice agencies and locations. Engaging families is also vital because the selection of a hospice location may vary for each patient depending on their individual care needs and available support.

Addressing the needs of patients dependent on transfusions who seek hospice care requires policy-level interventions at both the state and federal level. One potential approach is to implement a model allowing patients to enroll in hospice while still receiving disease-directed treatment, ensuring they benefit from both types of care simultaneously.19,27 This would necessitate higher reimbursement rates to adequately support such care. Alternatively, there is potential for the development of innovative “hospice” and payment models tailored specifically for patients requiring transfusions.28 Efforts are underway to advocate for improved coverage and policies, exemplified by the Improving Access to Transfusion Care for Hospice Patients Act of 2021. Furthermore, ongoing projects such as the Medicare Care Choices Model are exploring the feasibility of concurrent care options for patients, allowing them to receive services from selected hospice providers alongside other Medicare providers.

Future research directions

There are many efforts underway to try to improve longitudinal care of patients with hematologic malignancies including at the end of life. Current studies are geared toward facilitating conversations about patients' goals and values (Table 2); integrating palliative care services throughout patients' illness experience (Table 2); and maximizing supportive care measures for hospice-eligible patients (Table 3). For hospice-eligible patients, there are multiple pilot studies evaluating the feasibility of symptom-driven home transfusions while enrolled in hospice. Preliminary results support improvements in symptoms, QOL, and EOL care.42,43 Future research efforts must continue to address optimizing EOL care for all patients with hematologic malignancies, including those who are transfusion-dependent. These efforts can then inform policy-level changes to address the system change needed to optimize care models for patients who are transfusion-dependent near the end of life.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Your local hospice agency does not have transfusion capability, so you provide anticipatory guidance to Mrs. S on what to expect if she would continue vs not continue receiving transfusions. The palliative care team, which also has followed Mrs. S longitudinally, continues to meet with her. After another three weeks of transfusions, she elects to enroll in hospice and dies comfortably at home 1 week later.

Conclusions

EOL care among patients with hematologic malignancies is suboptimal, with challenges arising at the level of disease, patient, clinician, and system. Notably, accessing hospice services presents an added hurdle, particularly for transfusion-dependent patients. Multilevel interventions and strategies targeting patients, clinicians, systems, and policies are needed to overcome these challenges so that individuals with hematologic malignancies receive care aligned with their preferences and needs.

Acknowledgments

Kah Poh Loh is supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R00CA237744); National Institute of Aging (R03AG073985); Conquer Cancer American Society of Clinical Oncology and Walther Cancer Foundation Career Development Award. The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Rachel Rodenbach: no competing financial interests to declare.

Thomas Caprio: no competing financial interests to declare.

Kah Poh Loh: consultancy to Pfizer and Seagen; honoraria from Pfizer.

Off-label drug use

Rachel Rodenbach: Nothing to disclose.

Thomas Caprio: Nothing to disclose.

Kah Poh Loh: Nothing to disclose.