Abstract

Hydroxyurea has historically been the sole disease-modifying medication (DMM) for sickle cell disease (SCD). However, 3 newer DMMs, L-glutamine, voxelotor, and crizanlizumab, were approved for children and adolescents with SCD since 2017. Despite their emergence, treatment barriers, including access, affordability, and nonadherence, limit the optimization of DMMs in the clinical setting. Furthermore, there is limited work outlining real-world use and safety of the newer DMMs, and no published guidelines advise how best to select between DMMs or to use multiple in combination. Meanwhile, each DMM is associated with unique characteristics, such as tolerability, cost, and route of administration, which must be considered when weighing these options with patients and families. This article discusses DMMs for SCD and offers practical guidance on using the available DMMs in real-world settings based on published peer-reviewed studies and considering patient preferences. The recent withdrawal of one of these DMMs (voxelotor) from the market highlights the need for additional DMMs and evidence-based practices for adding DMMs and when to progress towards curative therapies.

Learning Objectives

Outline the approved DMMs for children and adolescents with SCD

Identify reasons for suboptimal response and DMM failure

Describe a practical approach to using DMMs in clinical practice

CLINICAL CASE

A 16-year-old boy with sickle cell disease (SCD, hemoglobin SS [HbSS]) presents for routine hematology care. While he has been prescribed hydroxyurea since the age of 4 years, his Hb is 7.2 g/dL, and he has had 4 emergency department visits in the last year for pain. He also reports having a poor quality of life and that managing SCD pain was interfering with his ability to do well in school and his plan to go to college. He says he wants to consider other medications, as he has no matched siblings or unrelated donors and is not yet interested in gene therapy given its potential risks.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a common, inherited hemoglobinopathy that affects millions worldwide and approximately 100 000 people in the United States.1 SCD is associated with multiorgan complications due to chronic hemolysis and vaso-occlusion and has historically resulted in early childhood mortality.2-4 However, the increasing use of hydroxyurea and the approval of additional disease-modifying medications (DMMs) provide new optimism for youths with SCD.5-6 Unfortunately, gaps in medication management in SCD remain and can be due to nonadherence, suboptimal dosing, variable response,7-11 and perceived ineffectiveness from a mismatch between the physiological response to a medication and treatment expectations and priorities.12 These gaps have a disproportionate impact on those with limited health care access and lead to increased acute care utilization and complications, especially for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with SCD.13,14 As such, tailoring the use of DMMs, using a shared decision-making approach, setting expectations up front, and implementing adherence-promoting strategies and standardized approaches to dose escalation are key to optimizing clinical outcomes for youths with SCD. This article outlines the DMMs that have been approved for youths with SCD, highlights common barriers to optimal medical management, and suggests a practical approach to their use in real-world practice based on published, peer-reviewed studies and considering patient preferences.

Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease

SCD is an autosomal recessive disease marked by a mutation in the beta globin chains of hemoglobin (Hb).3,4 This interchange results in the formation of abnormal sickle Hb (HbS), which is prone to polymerization in low oxygen states, causing red blood cells (RBCs) to form the “sickle” shape.4 SCD-related pathophysiology is driven by HbS polymerization, which leads to vaso-occlusion, chronic hemolysis, and inflammation.

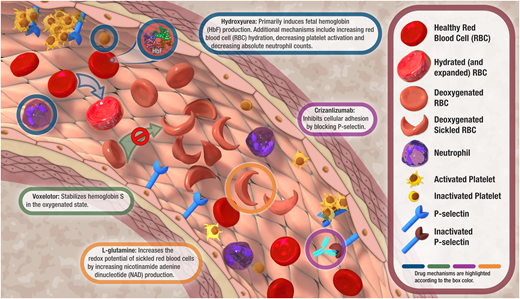

Vaso-occlusion results from the aggregation of sickled RBCs and causes end-organ ischemia. Acute vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) are often precipitated by stressors, such as infection,2 and most often manifest as pain.2 VOCs are the leading cause of SCD-related acute care utilization and are associated with substantial morbidity and health care costs.2,15 Given this, preventing VOCs has been a main focus in the development of DMMs for SCD. Furthermore, episodic insult from vaso-occlusion events such as acute chest syndrome (ACS), stroke, and splenic sequestration beginning in early childhood can lead to progressive end-organ dysfunction later in life.4 Chronic hemolysis related to increased RBC fragility causes chronic anemia, reticulocytosis, and endothelial dysfunction.4 Finally, inflammation is closely related to RBC sickling and vaso-occlusion, as this combination upregulates proinflammatory cytokines and signaling pathways.4,16 These mechanisms result in a vicious cycle marked by ischemia-reperfusion injury, reactive oxygen species generation, and endothelial adhesion, which promotes vaso-occlusion and in turn contributes to further inflammatory response.4,16 Exploration and further understanding of these complex pathophysiological mechanisms have driven decades of work to develop DMMs for SCD (Figure 1).

Proposed mechanisms of action of hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, voxelotor, and crizanluzimab. Voxelotor was an approved therapy that was recently withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns.

Proposed mechanisms of action of hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, voxelotor, and crizanluzimab. Voxelotor was an approved therapy that was recently withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns.

DMMs for SCD

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is the most studied and established DMM for SCD. It was approved for the treatment of SCD in adults in 1998, and its approval was expanded to include children in 2017.17 However, off-label hydroxyurea use in children with SCD has been common for over 20 years due to its ability to reduce VOCs, hospitalizations, and blood transfusions and increase survival in this population.18,19 Hydroxyurea modifies SCD pathophysiology primarily by inducing fetal Hb production, which ultimately reduces RBC sickling and clinical complications (Figure 1).20 Hydroxyurea also works by 1) combating hemolysis by increasing RBC hydration, 2) decreasing vaso-occlusion by reducing endothelial adhesion and upregulating nitric oxide production, and 3) reducing inflammation by decreasing absolute neutrophil counts.20 By virtue of these mechanisms, hydroxyurea can also cause myelosuppression, thus necessitating ongoing laboratory monitoring when used. The 2014 SCD guidelines recommend offering hydroxyurea at 20 mg/kg/d to children with HbSS and HbSβ0 as early as 9 months of age, and providers are encouraged to escalate the prescribed hydroxyurea dose by 5 mg/kg/d every 8 weeks to a maximum dose of 35 mg/kg/d or 2000 mg daily while maintaining an absolute neutrophil count of at least 2000/μL and a platelet count of 80 000/μL or greater.21 Despite its well-documented efficacy in clinical trials for children,18,19 hydroxyurea remains underutilized.5

L-glutamine

L-glutamine was approved in 2017 for the treatment of children with SCD aged 5 years or older.22 L-glutamine is an amino acid proposed to work by reducing oxidative damage and increasing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide production, which ultimately increases the redox potential of sickled RBCs (Figure 1).23 However, its exact therapeutic mechanism of action remains unclear.24 A phase 3 clinical trial showed that L-glutamine decreased the median number of VOCs by 25%, the median number of hospitalizations by 33%, and the frequency of ACS episodes by 14% but did not affect Hb concentration or other hemolysis markers.25 While laboratory monitoring is not required, there is limited information about the safety of L-glutamine in those with diminished hepatic and renal function. A recent study evaluating the real-world use of L-glutamine suggests that it can improve clinical outcomes for pediatric patients with SCD outside of a clinical trial setting.26 However, L-glutamine is more expensive than hydroxyurea and some real-world data suggest there may be barriers to accessing and/or tolerating L-glutamine.23,26 These lingering questions highlight the importance of shared decision-making and multidisciplinary management when considering this newer therapy for SCD.

Voxelotor

Although it was withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns from ongoing international studies,27 voxelotor was approved in 2019 for the treatment of individuals with SCD aged 12 years or older and in 2021 for children aged 4 years and up in 2021.28 Voxelotor acts to stabilize the HbS in the oxygenated state to prevent polymerization, RBC sickling, and hemolysis.29 In the first phase 3 clinical trial, it was shown that voxelotor increased Hb and reduced hemolysis markers, including indirect bilirubin and reticulocytosis.30 Subsequent real-world-use studies in the United States also showed increased Hb, reduced VOCs, and reduced VOC-related hospitalizations among those receiving voxelotor.31 Unfortunately, an imbalance in fatalities and vaso-occlusive events among those receiving voxelotor during ongoing international studies indicates the need to further study this DMM to determine whether it has a role in SCD management.

Crizanlizumab

Crizanlizumab was approved in 2019 for individuals aged 16 years or older with SCD.32 This medication is a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits cellular adhesion by blocking P-selectin, which is expressed on activated platelets and endothelial cells and contributes to platelet aggregation and vaso-occlusion. Crizanlizumab is limited to older youths with SCD and, unlike hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, and voxelotor, is administered via intravenous infusion. A phase 2 placebo-controlled trial showed that 5 mg/kg of crizanlizumab every 4 weeks reduced the rate of VOCs and the median time to first and second VOC,33 leading to its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration.32 Despite these promising results, a recent update from the phase 3 trial showed no significant difference in annualized VOCs between crizanlizumab and placebo,34 raising uncertainty surrounding crizanlizumab's role in decreasing VOCs for youths with SCD. On the other hand, crizanlizumab may have a role for men with SCD complicated by priapism, as a case series reported that a few men had a decrease in priapism episodes with crizanlizumab.35 Meanwhile, real-world use studies of crizanlizumab are mixed, with one small single-center cohort reporting high discontinuation rates and no significant decrease in acute care visits36 but another showing a significant reduction in care utilization and positive patient-reported experiences with the medication.37 More work is needed to further elucidate the clinical impact and utility of this newer medication.

Suboptimal response and DMM failure

Multiple factors should be considered when evaluating why response to DMMs may be suboptimal or fail to improve outcomes in youths with SCD. For instance, poor disease and DMM knowledge, medication nonadherence,8 suboptimal dosing,7 and variable response9-11 may contribute to treatment failure. Also, perceived ineffectiveness from a mismatch between the physiological response to a medication and treatment expectations and priorities of patients and providers may also contribute to a suboptimal medication response.12

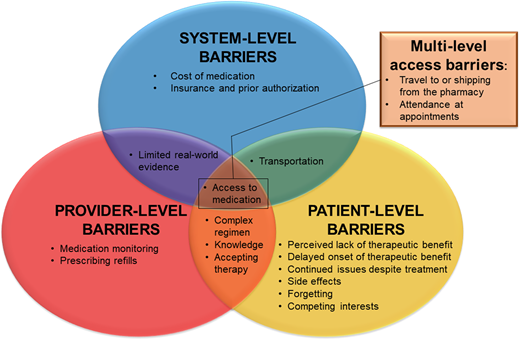

Poor medication adherence is common across pediatric chronic diseases,38 including youths with SCD, and is a known reason for suboptimal response to hydroxyurea.5,8 It is important to recognize that there are numerous nonadherence barriers. These can exist at the patient/family-, provider-, and system-level or even at overlapping levels. Figure 2 illustrates adherence barriers to consider and provides a framework to identify where interventions may be needed to optimize DMM adherence and treatment.8,14

Disease-modifying medication adherence barriers to consider and a framework for identifying where and at what level(s) intervention may be needed.

Disease-modifying medication adherence barriers to consider and a framework for identifying where and at what level(s) intervention may be needed.

While there are no definitive strategies to improve medication adherence in SCD, clinicians should routinely assess DMM adherence and associated adherence barriers with these youths and their families given the negative impact that nonadherence can have on outcomes.8 While multiple strategies can measure adherence, the simplest method is via self-report.8 Self-report provides the patient/family perspective and insight into their adherence, allowing for self-reported nonadherence to be identified and addressed. Unfortunately, these reports are inherently subjective and tend to overestimate adherence in other childhood conditions.39 Furthermore, providers need to be direct and ask about adherence at visits, as normalizing nonadherence and explicitly asking about missed doses (ie, “When was the last time you missed a dose or how many doses have you missed?”) is associated with self-reported nonadherence disclosure.40 Laboratory measures can also be considered when measuring adherence (ie, fetal Hb for hydroxyurea).41 Even so, laboratory values as adherence measures can be limited because they do not quantify adherence or account for other patient-level, biological characteristics outside of adherence (eg, polymorphisms, variable medication response) that may confound these biomarkers.9-11 Pharmacy refill records may provide an option to objectively assess adherence, but using these in clinical practice can be challenging if these data are not readily or electronically available, if the medication dose is adjusted (ie, hydroxyurea), or if patients have stockpiles of the medication from previous refills. Given these limitations, there is a need to develop validated adherence measures to supplement these existing strategies.

Despite the lack of proven interventions, there are practical suggestions to address common adherence challenges for youths with SCD and their families. For instance, 1) simplifying the dosing regimen (eg, do not prescribe doses that alternate each day and instead prescribe the same dose daily), 2) switching formulations (eg, capsule hydroxyurea to dissolvable hydroxyurea if difficulty ingesting the medication is causing nonadherence), 3) educating patients and families about the expectations for the therapy (eg, L-glutamine may reduce the frequency of painful VOCs but it may not prevent all VOCs), 4) setting reminder alerts, and/or 5) encouraging an adult caregiver to oversee medication administration are reasonable interventions with limited downsides.

Second, the prescribed medication dose should also be reviewed. For instance, beyond escalating hydroxyurea for growth in youths with SCD, providers must also ensure that the hydroxyurea dose is escalated to the maximum level that avoids myelosuppression as it optimizes clinical effect.7 On the other hand, if patients report nonadherence to hydroxyurea because of side effects (eg, hair loss), it could be reasonable to decrease the dose in an attempt to mitigate side effects and improve adherence. Since home medication-dosing errors are common,42 routinely reviewing doses with patients and their caregivers can help to identify and correct errors to optimize response and avoid toxicities and side effects.

Third, while at least 1 clinical trial showed improved hematologic and clinical response with each of the DMMs that have been approved,18,25,28,33 it is important to consider that response to these therapies can be variable. For instance, in the initial pediatric trial, the mean change in Hb with voxelotor was 1.0 g/dL with a standard deviation of 1.2 g/dL,30 indicating significant interpatient variability in response. Also, as mentioned previously, hematological and clinical response with hydroxyurea may be affected by other factors, such as age and inherited polymorphisms.9-11

Finally, while the DMMs target specific aspects of SCD pathophysiology, some SCD complications have a complex pathophysiology (ie, chronic pain) that may not be targeted by the DMMs, leading to a limited impact on these outcomes. As such, recognition and discussion about the capabilities and limitations of each DMM at initiation and throughout treatment is needed to ensure that the DMM aligns with treatment expectations and priorities (Table 1).

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

When asked at the visit, the adolescent patient reported missing 2-3 doses per week of hydroxyurea since taking on managing this therapy himself in the last year. The provider confirmed that the patient was administering the prescribed dose but that he had also grown significantly and was only prescribed 21 mg/kg/d of hydroxyurea, whereas his previous maximum tolerated dose had been 28 mg/kg/d. Finally, the provider reviewed the patient's preferences with him. The patient continued to state that preventing pain was most important to him. To achieve this goal over the next year, the provider escalated the prescribed hydroxyurea dose to 28 mg/kg/d, the patient set daily reminder alarms on his phone, and his caregiver committed to overseeing hydroxyurea administration.

A practical approach to using DMMs in clinical practice

Although there is increasing evidence for these DMMs, their real-world effectiveness and ability to ameliorate disease complications compared to curative options are still being investigated. Furthermore, there are no published guidelines on how to select between or to use the DMMs in combination. As such, shared decision-making models that consider the clinical presentation, patient/family preferences and values, treatment barriers (eg, tolerability, accessibility, cost, etc), intended outcomes, and other factors should be used to optimize treatment.

Some of the patient and medication characteristics to consider when initiating or adding a DMM are included in Table 1. Some patient characteristics and preferences, such as age, side effects, and preferred medication administration route, can be used to guide DMM selection. For instance, adolescents who struggle with hydroxyurea adherence may benefit from adding crizanlizumab, which is administered monthly and intravenously, especially if pain and/or ACS episodes are their primary symptoms. L-glutamine may be reasonable to initiate in young children whose families decline hydroxyurea due to concerns about fertility and/or who are unable to obtain frequent laboratory monitoring. L-glutamine may also be a reasonable option for young children who continue to have frequent pain or ACS despite high adherence to maximally tolerated doses of hydroxyurea. Finally, the amount of evidence and the efficacy of each of these therapies at achieving a specific outcome (eg, reducing VOCs) need to be weighed when deciding which DMM to initiate or add. For instance, an adolescent male with frequent episodes of debilitating priapism may benefit from trialing crizanlizumab.35

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

While the patient's Hb increased to 8 g/dL with optimized hydroxyurea exposure over the next year, he still had 3 emergency department visits for pain, including an episode of priapism. The provider reviewed the available DMMs with the patient and his caregiver, including their routes of administration, side effects, availability, clinical trial findings, and cost (Table 1), and used a shared decision-making approach. The patient ultimately decided to initiate crizanlizumab, but he reported that he would be willing to consider L-glutamine in the future.

Conclusion

Patient-centered management approaches for youths with SCD are needed as the SCD treatment landscape continues to evolve. Despite encouraging evidence, there is still much to learn about the use of DMMs in the real world, in combination, and in comparison to curative options for SCD. Furthermore, patient-, provider-, and system-level barriers may affect their success. Given this, shared decision-making, open communication, adherence monitoring, adherence-promoting strategies, and appropriate expectation setting are vital to optimizing medical treatment and improving patient outcomes. Although there are no approved guidelines on selecting between DMMs, we provide 1 perspective of important considerations to weigh when discussing these medications with youths with SCD and their families. Additional work is needed to further evaluate real-world outcomes with the newer DMMs and to further tailor and optimize their use in clinical practice.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Susan Creary: research funding: National Institutes of Health.

Joseph Walden: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Joseph Walden: There are no off-label drug use or disclosures to report.

Susan Creary: There are no off-label drug use or disclosures to report.