Abstract

The term heparin resistance is likely best defined as the failure of an appropriate dose of unfractionated heparin (UFH) to achieve a predetermined level of anticoagulation. Unfortunately, and despite many prior reports, there is no established consensus as to what either the appropriate dose or the predetermined level should be. Traditionally, assays used to monitor anticoagulation with UFH have been clot based, including the activated partial thromboplastin time, used for patients on the ward or intensive care unit, and the activated clotting time, used for patients undergoing vascular interventions and cardiopulmonary bypass. Unfortunately, these tests may be highly influenced by other factors occurring in many patients, especially those with inflammation or acute infection, as noted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many hospitals have thus moved to anti-Xa testing for heparin monitoring. Another important factor in defining heparin resistance includes dosing, whether weight-based or total daily dosing is used, as initial reports of heparin resistance described daily doses independent of body weight. Multiple causes of apparent heparin resistance include hypercoagulability, antithrombin deficiency, andexanet alfa used for direct oral anticoagulant reversal, thrombocytosis, and antiphospholipid antibody syndromes. Treatment options for managing patients with heparin resistance include weight-based dosing and administration of additional UFH, antithrombin supplementation, or the use of an alternative anticoagulant such as the direct thrombin inhibitors bivalirudin or argatroban.

Learning Objectives

Review heparin resistance as defined in current reports on various patient populations, including those with critical illness

Describe the pharmacology of heparin anticoagulation, its requirement for antithrombin, and antithrombin- independent alternatives

CLINICAL CASE

A 64-year-old 100 kg man with end-stage pulmonary dysfunction secondary to interstitial lung disease underwent bilateral lung transplantation in March 2021. He was extubated on postoperative day (POD) 1 and transferred to the ward on POD 2. On POD 10 he developed acute hypoxemic respiratory failure requiring reintubation and mechanical ventilation. Chest radiographs showed bilateral edema with patchy opacities, and the ratio of partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) on arterial blood gas of 80 suggested severe acute lung injury. Laboratory tests demonstrated fibrinogen 780 mg/dL, D-dimers 5200 ng/mL, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.2, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 35 seconds, antithrombin 78%, a platelet count of 100 000 per microliter, and a white blood count of 12 000 per microliter. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics were started after cultures were sent. Intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH) was started at an infusion rate of 1000 U/h, with a goal aPTT of 50-70 seconds based on critical illness and high D-dimers, and the aPTT was checked every 4-6 hours. After 24 hours, despite 2000 U/h dosing, the aPTT was 38 seconds, raising concerns for heparin resistance in the setting of potential COVID-19.

Introduction

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) are mainstay parenteral anticoagulation therapies for hospitalized patients. Unlike direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs), UFH and LMWH heparin require antithrombin (AT) to exert their anticoagulant activity. Over 75 years ago, heparin “hyporesponders” were reported based on decreased UFH dose-responses using whole blood clot-based coagulation assays.1 The term heparin resistance was reported by Levine et al in 1994, based on a fixed dosing of over 35 000 units per day.2 Over time, clinicians have adopted this term to describe any lower-than-expected response to UFH based either on predetermined infusion rates or on doses administered over 24 hours, as described in a recent International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostatis (ISTH) communication.3 The American College of Chest Physicians 9th edition antithrombotic therapy guidelines define heparin resistance as any “situation wherein patients require unusually high doses of heparin to achieve a therapeutic aPTT.”4 Thus, while heparin resistance has become a commonly used clinical term, its precise definition based on data or consensus is lacking.

Drug resistance to a medication is best defined as reduced responsiveness to defined therapeutic dosing, which may relate to prior exposure.5 Other common causes of resistance include inadequate dosing or variability in the biologic target.6 In the case of UFH, resistance may be suspected when routine doses do not achieve expected target values in laboratory tests of coagulation. The dosing regimen and type of monitoring tests used are important considerations and oftentimes underappreciated in the assessment of heparin resistance.3,7 Moreover, what defines an excessive versus adequate UFH dose may depend on the indication.

The patient in the clinical vignette provides an opportunity to discuss several important points related to understanding heparin resistance. For example, the patient was receiving 2000 U/h of UFH, totaling 48 000 U/d, and would thus be considered heparin resistant if applying the frequently used criteria of requiring >35 000 U/d.3 However, it is often appropriate to use weight-based dosing of UFH, which may necessitate higher levels of UFH for adequate support even in the absence of any drug resistance. In addition, the patient was evaluated using a clot-based aPTT assay to assess anticoagulation, which is susceptible to a number of limitations that will be detailed further. Here we will use the case study and published literature to (1) review definitions of heparin resistance, (2) discuss limitations in assays used for UFH monitoring, and (3) consider clinical approaches for patient management.

Defining heparin resistance

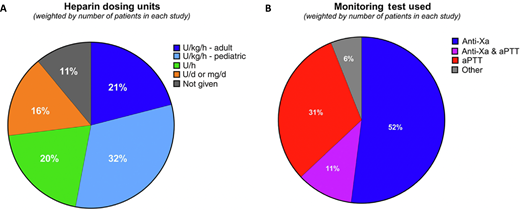

Clinicians commonly use the term heparin resistance without specific criteria. Recently, we attempted to capture the most commonly used definition of heparin resistance using a 2-pronged approach that included a literature review and provider survey.3 The survey was available to all 348 members of ISTH's Perioperative and Critical Care Thrombosis and Hemostasis Scientific and Standardization Committee, with a response rate of 33% resulting from 115 respondents. Together with the literature review, the survey highlighted the variability in UFH dosing strategies for critically ill patients. Specifically, the heparin dosing most commonly reported was weight based, based on publications (53%) and ISTH survey respondents (80.4%) (Figure 1A). We identified a fairly even divide between use of aPTT and anti-Xa testing to monitor UFH response (Figure 1B).3

UFH dosing units (A) and primary monitoring assays used (B) to define heparin resistance in a recent literature survey. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024.

UFH dosing units (A) and primary monitoring assays used (B) to define heparin resistance in a recent literature survey. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024.

Based on our study, the most common definition of heparin resistance was >35 000 U/d (Figure 2). This finding likely relates to the aforementioned 1994 report using the term heparin resistance, which has been cited and repeated in additional publications.2,3 However, no consensus among using weight-based or total UFH dosing was reported to define resistance.

Results from the ISTH Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee survey asking respondents (N = 115) what dose of heparin they consider “too much” in trying to achieve their target value on their monitoring test. Error bars represent upper 95% Wilson confidence limit. The percentage response for each value is provided above the error bar. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024.

Results from the ISTH Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee survey asking respondents (N = 115) what dose of heparin they consider “too much” in trying to achieve their target value on their monitoring test. Error bars represent upper 95% Wilson confidence limit. The percentage response for each value is provided above the error bar. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024.

Recent CHEST guideline updates fail to mention heparin resistance, likely due to the focus on agents other than UFH.8,9 However, issues related to UFH dosing and heparin resistance have gained prominence and become more notable with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, as many patients have required higher- than-expected doses of heparin as part of their treatment for COVID-19 or if they required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).3,7,10 While the hypercoagulability associated with acute critical illness has been previously reported in the literature, the overwhelming number of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the resurfacing of heparin resistance as an area of concern.7

Determining heparin resistance

Diagnosing heparin resistance depends on the anticoagulation target level, laboratory test used, and clinical scenario for UFH use. Current laboratory tests vary by institution and include chromogenic assays, clot-based assays, or both. The most common clot-based testing is the plasma-based aPTT used for hospitalized patients admitted to the ward or ICU. For patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) or vascular interventions, like in the cardiac catheterization lab or for other procedures, including radiology, the whole blood activated clotting time (ACT) may be used as a point of care test. Specific considerations related to these tests will be considered.

Activated partial thromboplastin time

The aPTT is a citrated plasma clot-based assay used to monitor UFH and other anticoagulants, including DTIs. The aPTT assay uses a contact activator alongside recalcification of plasma and determines the time for clot formation in seconds, with a target of 1.5 to 2.5 times the control value for UFH monitoring. Notably, the relationship between aPTT and heparin concentration is not linear or log-linear. Moreover, as with other clot-based assays, the aPTT is influenced by a number of circulating proteins that contribute to coagulation and is thus not specific for determining UFH levels. Specifically, the aPTT may be decreased in the setting of inflammation related to increased levels of acute phase proteins, like factor VIII and fibrinogen, or may be increased related to congenital or acquired factor deficiency or the presence of inhibitors, as discussed below.

Activated clotting time

The ACT is a whole blood assay used to monitor high levels of heparin well above the range monitored by aPTT. The ACT uses kaolin, diatomaceous earth, or glass beads to enhance contact activation and reduce the time from 7-10 minutes to 100-150 seconds, depending on the specific ACT technology. The ACT is more linear at higher UFH levels, including those used during CBP, where target levels are 2 to 6 IU/mL for UFH.11 Several patient- related (eg, acquired or congenital factor deficiency states, inhibitors like antiphospholipid antibodies) and procedure-related (eg, CPB-related hypothermia or hemodilution) conditions can prolong ACT values independent of heparin, and these cannot be accounted for using the reference standard curve.

Chromogenic anti-Xa assays

Chromogenic anti-Xa assays assess factor Xa enzymatic activity using synthetic chemical substrates for UFH monitoring. Anti-Xa assays are increasingly used for UFH monitoring due to the specificity in quantifying anti-Xa activity without influence from many plasma-based factors that affect the aPTT and result in discordance between UFH levels and aPTT.12 Some chromogenic anti-Xa assays include exogenous antithrombin (AT), which, by saturating the system, reveals the heparin concentration, while those without exogenous AT are used to determine heparin activity. Understanding which assay is performed is relevant in determining whether a patient has AT-related heparin resistance. Anti-Xa testing has a major advantage over clot-based aPTT assays in that results are not affected by acquired factor deficiency states, antiphospholipid antibodies, acute phase proteins, or other circulating factors impacting the aPTT.

Potential causes of heparin resistance

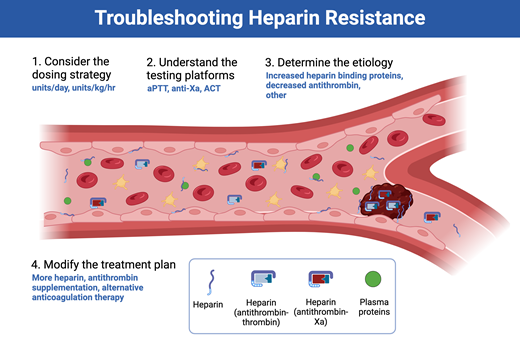

The mechanisms behind most cases of heparin resistance relate to the presence (or absence) of heparin-binding blood components, including antithrombin (Figure 3), as detailed below.7

Causes of heparin resistance are most often related to either increases in heparin-binding proteins or decreases in antithrombin activity. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Causes of heparin resistance are most often related to either increases in heparin-binding proteins or decreases in antithrombin activity. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Platelets and platelet factor 4

Multiple plasma and extracellular matrix proteins can bind or neutralize UFH. This includes platelet factor 4 (PF4), von Willebrand factor, factor VIII, and others. In addition, for whole blood clotting tests, including the ACT, antiplatelet agents may increase the test's responsiveness to heparin, while agents or conditions that lead to rapid platelet activation decrease the test's response to heparin. PF4, a chemokine released by activated platelets, was previously studied as a specific reversal agent for UFH and compared to protamine. This is particularly relevant for patients with thrombocytosis, especially during CBP, as platelets can degranulate and release large amounts of PF4.7 Recombinant PF4 has been studied for UFH reversal in cardiac surgical patients requiring CPB.13 Interestingly, the study showed PF4 could reverse the effects of heparin, supporting it as a potential mechanism for heparin resistance, especially in patients with thrombocytosis.

Coagulation factors

Elevated levels of fibrinogen and factor VIII may appear to alter heparin responsiveness, an effect especially exaggerated when using aPTT and other clot-based assays to measure heparin response. Others have used the term pseudo heparin resistance to categorize apparent heparin resistance when the aPTT is shortened due to the influence of elevated factor VIII or fibrinogen. Hypercoagulable states that increase levels of activated clotting factors such as factor VIIa or factor XIIa may also result in a shortened activated clotting time.14 Finally, mutations in factor V (eg, factor V Leiden), prothrombin, and other coagulation factors can occur, which may contribute to heparin resistance by increasing factor levels or activity, but are less common.15

Antithrombin

AT is commonly implicated as a cause of heparin resistance. Acquired AT deficiency may be related to recent heparin treatment, especially in cardiac surgery with CBP due to the higher UFH levels that are needed. This area is the focus of previous and future clinical trials evaluating AT repletion. AT supplementation improves anticoagulation based on laboratory testing, is commonly used in cardiac surgical patients, and is reported for use in ECMO and ICU patients.16 Patients with preexisting antithrombin polymorphisms may also potentially be at risk for heparin resistance.

Andexanet alfa

Specific anticoagulant reversal agents are available for non– vitamin K oral anticoagulants and include andexanet alfa, a decoy factor Xa mimetic, used to reverse factor Xa inhibitors, including low-molecular-weight heparin. There are increasing reports of cardiac surgical patients receiving andexanet alfa for apixaban or rivaroxaban reversal and demonstrating heparin resistance, which likely relates to its ability to bind to UFH without exerting an anticoagulant effect.17

Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 and other acute infections

The hypercoagulability related to COVID-19 alongside the massive number of patients seen worldwide during the pandemic likely contributed to the increased heparin resistance reported in recent years. Although the hypercoagulability associated with acute infection was previously reported, the increased risk of thromboembolic events, including clotting of ECMO and dialysis circuits in patients anticoagulated with UFH, increased the awareness of heparin resistance.18 Heparin resistance in COVID-19 likely relates to many factors, which include increased fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, and factor VIII, despite normal AT levels, especially in the setting of endothelial injury and potential for fibrinolytic suppression.18

Patient management and treatment

The approach to patients with heparin resistance involves consideration of multiple factors, including the dosing regimen, type of coagulation test used, and the indication for anticoagulation. The patient presented in the clinical vignette received increasing amounts of heparin over a fairly long time frame before an anti-Xa test was used; yet, it is important to recognize that patients with major thrombotic events, such as acute pulmonary embolism, require faster anticoagulant titration. Independent of indication, treatment options for heparin resistance include use of additional heparin, supplementation with AT, or the use of alternative anticoagulants (eg, DTIs like bivalirudin or argatroban). In this section we provide our approach to managing patients with heparin resistance.

Assess dosing

As described above, there is no consensus on what heparin level is sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of heparin resistance, and providers may be inclined to use >35 000 U/d as a threshold. We support the use of weight-based dosing rather than a daily maximum value, as patients with larger body mass indices will likely require increased doses, and highly recommend weight-based measures for determining resistance. Admittedly, even when using weight-based dosing, it remains unclear what heparin levels should be considered excessive, though the majority of providers appear to use >30 U/kg/h (Figure 2). Notably, heparin resistance is an alteration in the heparin dose-response curve or heparin responsiveness, and, in most cases, additional heparin may very well provide an adequate dose-response. If not, and the determination is already weight-based, it is important to next consider the type of assay used to assess heparin response, as discussed below.

Coagulation testing

Given the aforementioned limitations of clot-based testing for heparin response, many institutions rely on the chromogenic anti-Xa assay to assess heparin levels. Anti-Xa assays are often available even in settings where the aPTT is used predominantly; in these setting, heparin levels in patients not achieving aPTT goals should be determined using an anti-Xa assay, with a common target range of 0.3-0.7 units/mL.

AT supplementation versus alternate anticoagulants

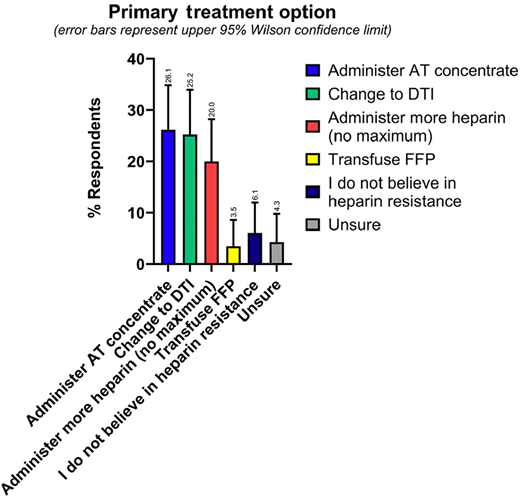

As our recent survey demonstrates, in practice, there is a fairly even split between using AT concentrate versus changing to a DTI as the primary treatment option for heparin resistance, which were both favored slightly more than administering more heparin (Figure 4).3 Since there are no treatment guidelines favoring one approach over another, providers may base their management plan on any number of factors, including personal and institutional experience, indication, and cost.

Results from the ISTH Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee survey question asking respondents(N = 115) their primary treatment option if they encountered heparin resistance. Error bars represent upper 95% Wilson confidence limit. The percentage response for each value is provided above the error bar. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024. FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

Results from the ISTH Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee survey question asking respondents(N = 115) their primary treatment option if they encountered heparin resistance. Error bars represent upper 95% Wilson confidence limit. The percentage response for each value is provided above the error bar. Reprinted with permission from Levy et al., JTH 2024. FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

Heparin exerts an anticoagulant effect via AT, so it is intuitive that patients with low AT levels may benefit from supplementation. Notably, AT levels may fall by approximately 30% after a patient first receives heparin, with levels gradually increasing again over time. The dosing of AT concentrate and the target level are, unfortunately, poorly defined, and AT concentrates are expensive. Although plasma contains AT and has been used to increase levels in certain patients, it takes approximately 4 units of plasma to provide 1000 units of antithrombin, posing potential transfusion-related risks.

Some providers chose to switch to an alternative anticoagulant even in the presence of low AT levels, given the cost associated with pharmacologic supplementation. Bivalirudin and argatroban are parenteral DTIs currently available for use in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and are increasingly used for ECMO and for anticoagulation in patients with heparin resistance.19-21 DTIs inhibit thrombin directly without a requirement for AT and are commonly used in critically ill patients. Of note is that DTIs are generally monitored using the aPTT and are thus affected by hypercoagulability.22 However, as previously reported, DTIs both have different effects on thrombin generation and have no current reversal agent, though this fact is attenuated by relatively short half-lives.7,23

CLINICAL CASE RESOLUTION

In our patient, the UFH dose was increased every 3-4 hours over the following 18 hours to 3000 U/h. The aPTT was 48 seconds, with a goal of 50-70 seconds. Given this, an anti-Xa level was ordered. The patient's anti-Xa level came back as 0.75 U/mL, and a repeat aPTT was 49 seconds. UFH monitoring was changed to an anti-Xa goal of 0.6-0.8 U/mL, consistent with the high-dose anticoagulation regimen used clinically.

Summary

Managing patients with heparin resistance requires a multifaceted approach that includes adjusting to weight-based doses, considering the specific laboratory-based anticoagulation tests used, and administering additional heparin or pharmacologic interventions. While heparin resistance may be encountered in a number of clinical scenarios, patients with critical illnesses are most at risk, especially those with infectious or other highly inflammatory disease that increase acute phase and heparin-binding proteins or decrease AT levels. Heparin resistance should be suspected in patients not achieving target values on anticoagulation tests, after ensuring appropriate weight-based heparin administration. Although standard criteria are not reported, data suggest that the majority of providers diagnose heparin resistance in patients requiring >30 units/kg/h UFH. Specific interventions for heparin resistant patients not achieving target values on anti-Xa tests include administering additional heparin, supplementing AT, and switching to a DTI like bivalirudin or argatroban. Management strategies remain diverse, and future studies are needed to inform treatment protocols for patients with heparin resistance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Cheryl L. Maier: no competing financial interests to declare.

Jean M. Connors is on the scientific advisory boards and consults for Abbott, Anthos, BMS, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Werfen.

Jerrold H. Levy is on advisory or steering committees for Merck, Octapharma, Takeda, and Werfen.

Off-label drug use

Cheryl L. Maier: Nothing to disclose.

Jean M. Connors: Nothing to disclose.

Jerrold H. Levy: Nothing to disclose.