The objective of this study was to determine the frequency and load of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA in anti-HBc–positive first-time blood donors; it was designed to contribute to determining whether anti-HBc screening of blood donations might reduce the residual risk of posttransfusion HBV infection. A total of 14 251 first-time blood donors were tested for anti-HBc using a microparticle enzyme immunoassay; positive results were confirmed by a second enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For the detection of HBV DNA from plasma samples, we developed a novel and highly sensitive real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. The 95% detection limit of the method amounted to 27.8 IU/mL, consistent with the World Health Organization (WHO) international standard for HBV DNA. A total of 216 blood donors (1.52%) tested anti-HBc–positive in both tests, and 205 of them (16 HBsAg+, 189 HBsAg−) were tested for HBV DNA. In 14 (87.5%) of the HBsAg-positive blood donors, HBV DNA was repeatedly detected, and in 3 (1.59%) of the HBsAg-negative donors, HBV DNA was also found repeatedly. In the 3 HBV DNA–positive, HBsAg-negative cases, anti-HBe and anti-HBs (> 100 IU/L) were also detectable. HBV DNA in HBsAg-negative as well as HBsAg-positive samples was seen at a low level. Thus, HBV DNA is sometimes found in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc–positive, and anti-HBs–positive donors. Retrospective studies on regular blood donors and recipients are necessary to determine the infection rate due to those donations. Routine anti-HBc screening of blood donations could probably prevent some transfusion-transmitted HBV infections.

Introduction

The risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been reduced by screening all blood donations for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) since 1970. It was generally accepted that the disappearance of HBsAg indicates the clearance of HBV. Meanwhile, many reports on positive findings for HBV DNA in the liver and blood of HBsAg-negative individuals positive for antibodies against HBV core antigen (anti-HBc) and/or HBsAg (anti-HBs) have been published.1-8 Blum et al described, in a patient with HBsAg-negative chronic hepatitis who was positive for anti-HBc, anti-HBs, and antibodies against HBe antigen (anti-HBe), a latent HBV infection in hepatocytes with extrachromosomal presence of a full-length viral genome.9 Michalak et al demonstrated the long-term persistence of HBV DNA in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients up to 70 months after complete clinical, biochemical, and serologic recovery from acute viral hepatitis.10 Rehermann et al showed that traces of HBV were often detectable in the blood for many years after clinical recovery from acute hepatitis, despite the presence of serum antibodies and HBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs).11 These findings suggest that sterilizing immunity to HBV frequently fails to occur and that traces of virus can maintain the CTL response for decades, apparently creating a negative feedback loop that keeps the virus under control, perhaps for life. This was supported by Pasquetto et al, who showed that cytoplasmic HBV nucleocapsids and their cargo of replicative DNA intermediates survive CTL-induced apoptosis of hepatocytes in vitro,12 and by other groups that demonstrated ongoing viral replication in the liver tissue of patients and healthy individuals after loss of HBsAg.13-15Furthermore, reactivation of apparently cured HBV infection has been described under chemotherapy or immunomodulating therapy after renal and bone marrow transplantation, and in some of these cases a reverse seroconversion from anti-HBs to HBsAg has been observed.16-19

The residual risk of posttransfusion HBV infection has been calculated by several groups in the United States and Germany on the basis of HBV incidence data and the duration of the early window period until HBsAg becomes detectable to be 1:63 000 and less than 1:100 000 blood donations, respectively.20,21 It has been shown that blood donations of HBsAg- and anti-HBs–negative but anti-HBc–positive HBV carriers can cause posttransfusion hepatitis B.22;23 Thus, Mosley et al suggested that anti-HBc screening of blood donations might prevent HBV transmission from HBsAg-negative blood donors and that donors positive for anti-HBs as well should be considered noninfectious for HBV.24 The feasibility of routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening of blood donations in a blood bank setting has been shown by Roth et al.25 In Germany, the Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI, Langen, Germany), the institute that defines German Drug Law and is responsible for specific regulations for the processing of blood components, decided on the introduction of HCV nucleic acid amplification technology (NAT) for the release of erythrocyte and platelet concentrates starting from April 1, 1999. The value of HBV NAT has been a matter of debate.26-29However, it seems to be less useful because the nucleic acid load is often markedly lower than it is in HCV infection, so that an adequate HBV NAT can only be performed on a single (not pooled) blood donation.

The aim of this 5-year prospective study was to reevaluate the prevalence of anti-HBc among German first-time blood donors and to determine the frequency and load of HBV DNA in anti-HBc–positive plasma samples using a sensitive real-time PCR assay. Thus, it was intended to contribute to determining whether routine anti-HBc screening of blood donations provides any concrete benefits with regard to HBV risk reduction.

Materials and methods

Blood specimens

Whole blood samples were collected from 14 251 volunteer first-time blood donors in 5.5 mL tubes containing potassium-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) at a concentration of 1.6 mg EDTA per milliliter of blood (Monovette; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Such samples were centrifuged at 3291g for 4 minutes, and EDTA-plasma was separated within 24 hours. Plasma specimens were stored at 4°C to 8°C for no longer than 72 hours or for longer at −50°C until further processing. The sex and age distribution in the first-time blood donor population was as follows: women 18 to 24 years, 28.52%; 25 to 34 years, 12.03%; 35 to 54 years, 13.61%; 55 to 65 years, 1.72%; and men 18 to 24 years, 18.48%; 25 to 34 years, 12.09%; 35 to 54 years, 11.30%; and 55 to 65 years, 2.24%. The study abided by the rules of the internal review board of the University of Lübeck, Germany, and the Helsinki protocol.

Standard and control specimens

The first WHO international standard for hepatitis B virus DNA for NAT assays (code number 97/746),30kindly provided by Dr John Saldanha, National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), Herts, United Kingdom, was used to determine the detection limit of the method and to quantify HBV DNA–positive samples in international units of HBV DNA per milliliter of plasma. HBV DNA–positive plasma samples from an external quality control program lyophilized and kindly provided by INSTAND (Düsseldorf, Germany) were used as positive samples for the development and optimization of the method.

Hepatitis B serology

Anti-HBc screening was performed using an automated microparticle enzyme immunoassay (AxSYM Core; Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany). Reactive samples were retested in duplicate and considered to be repeatedly reactive if at least 1 of the 2 repetitions also gave a positive result. Repeatedly reactive samples were confirmed by a second enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Enzygnost Anti-HBc monoclonal; Dade Behring, Liederbach, Germany). Only samples that were positive for anti-HBc in both tests were included in this study. Those samples were also tested for HBsAg (Ortho Antibody to HBsAg ELISA Test System 3; Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Neckargemünd, Germany), HBeAg (AxSYM HBe; Abbott), anti-HBc immunoglobulin M (IgM) (AxSYM Core-M; Abbott), anti-HBe (AxSYM Anti-HBe; Abbott), and anti-HBs (AxSYM AUSAB; Abbott). HBsAg-positive samples were confirmed by a second test (AxSYM HBsAg (V2); Abbott) and an appropriate neutralization assay (AxSYM HBsAg Confirmatory Assay; Abbott).

Nucleic acid isolation

DNA was prepared from 1 mL or, if available, 2 mL EDTA-plasma using the NucliSens Extractor (Organon Teknika, Boxtel, The Netherlands).31 32 To increase the nucleic acid yield, we added a first incubation step of samples together with the lysis buffer, which is based on guanidine thiocyanate at 60°C with horizontal shaking at 110 rpm for 30 minutes. The further isolation procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol for sample volumes between 200 and 2000 μL. Total nucleic acids from up to 2 mL plasma were eluted in 50 μL elution buffer of which 20 μL was investigated in one PCR experiment to detect HBV DNA and 3 μL was studied in a β-actin control PCR.

TaqMan PCR

For amplification and simultaneous detection of PCR products, we developed a novel approach based on the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (manufactured by Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ; distributed by Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) on the ABI Prism 7700 SDS (Applied Biosystems). Primers and fluorogenic TaqMan probe for HBV DNA detection were chosen after comparative analysis of 65 sequences containing the C region of the HBV genome, which were available from the GenBank Nucleotide Database using OMIGA software version 2.0 (Oxford Molecular, Oxford, United Kingdom). The sequences of the oligonucleotides are provided in Table 1. In addition, we performed a standard nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST Search via Internet at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast for the chosen oligonucleotides. For the forward primer, TaqMan probe, and reverse primer, we found 809, 779, and 818 hits, respectively, to HBV sequences that had been submitted to various databases. The sequence alignments ensured that the primers were homologous at the last 10 nucleotides at the 3′ end to 797 (98.52%) and 811 (99.14%) of the sequences, respectively. The TaqMan probe showed 100% homology or only 1 mismatch to 774 (99.36%) of the HBV hits, in comparison with 5 HBV sequences where 2 mismatches were found, which would probably lead to a loss of sensitivity. A total of 128 non-HBV BLAST hits each to only 1 of the HBV oligonucleotides ensured that no other organism could be detected with this method. The HBV TaqMan probes were labeled with VIC as reporter and TAMRA as quencher dyes and custom synthesized (Applied Biosystems); the HBV primers were synthesized elsewhere (TIB Molbiol, Berlin, Germany).

A human genomic sequence that was found to be detectable in human plasma was coamplified separately as a PCR control to prevent any false-negative results due to failure of nucleic acid isolation or PCR inhibition (TaqMan β-actin Control Reagents; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR experiments were carried out in special optical tubes (MicroAmp Optical Tubes/Caps; Applied Biosystems) in a total volume of 80 μL. Concentrations of MgCl2, HBV probe, and primers were optimized by means of chessboard titrations. Final concentrations were 5.5 mM for MgCl2, 550 nM each for HBV forward and reverse primer, and 300 nM for HBV probe. The concentration of the β-actin probe labeled with FAM and TAMRA was 200 nM, whereas those of the β-actin primers were 300 nM each. Thermal cycler conditions were 2 minutes at 50°C, 10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, and 1 minute at 61°C.

Threshold values were calculated as the upper 10-fold SD of the background fluorescence signal measured over the baseline from cycles 3 to 30. Highly positive samples (threshold cycle [CT] < 30) must be calculated separately by setting the baseline to the cycle before the exponential increase of the first PCR kinetics is to be observed. Results were interpreted as follows: CT less than 40 is positive; CT equal to 40 is negative.

To determine the 95% detection limit of the TaqMan HBV PCR, we investigated semilogarithmic dilutions of the first WHO international standard for HBV DNA NAT assays described above. The standard plasma preparation containing 1 × 106 IU/mL HBV DNA, genotype A, HBsAg subtype adw was diluted with HBV DNA–negative fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to 102.5, 102, 101.5, 10, and 100.5 IU/mL. Twenty-four 1-mL plasma samples of each concentration were processed in 5 consecutive runs separately through all steps of nucleic acid isolation and PCR. The quantification of HBV DNA–positive samples was carried out by means of a standard curve derived from these validation experiments.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 9.0 for Windows. The Kolmogorow-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate whether the results were normally distributed. Because spot checks had proven positive, significances of differences were analyzed using the Student t test. Correlation coefficients and corresponding significances were analyzed by the Pearson test. The 95% detection limit was calculated by means of probit analysis.

Results

HBV serology

A total of 216 (1.52%) of 14 251 first-time blood donors tested anti-HBc–positive in both tests, and 16 of them were identified as HBsAg carriers. Thus, 200 (1.40%) of our first-time blood donors were negative for HBsAg and positive for anti-HBc. Not a single sample tested positive for HBeAg or for anti-HBc IgM. An overview of the serologic test results is provided in Table2. Most anti-HBc–positive samples also showed anti-HBe and anti-HBs. In contrast, anti-HBc alone was to be seen rarely (0.08% of all). A total of 57 (0.40%) of the 14 251 donors were repeatedly reactive in the first but negative in the second anti-HBc assay.

HBV DNA

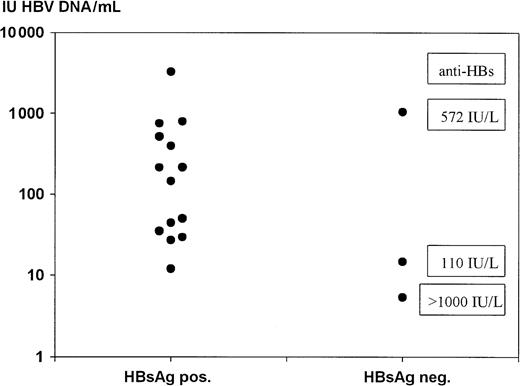

The 95% detection limit of the TaqMan HBV PCR from 1 mL plasma samples related to the WHO HBV DNA standard preparation was calculated by probit analysis and amounted to 27.79 IU/mL plasma (Tables3 and 4). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the standard samples ranging from 102.5 to 100.5 IU/mL tested in 5 validation experiments for estimating the detection limit. Because the detection limit was calculated on 1 mL plasma samples, it would correspond theoretically to about 14 IU/mL for 2 mL plasma specimens. A total of 205 of the anti-HBc–positive first-time blood donors (16 HBsAg-positive, 189 HbsAg-negative) were tested for HBV DNA, and in 62 cases 2 mL samples were available. In 14 (87.50%) of the HBsAg-positive blood donors HBV-DNA was repeatedly detected, and in 3 (1.59%) of the HBsAg-negative blood donors HBV DNA was also repeatedly found (Table5). In the 3 HBV DNA–positive, HBsAg-negative cases, anti-HBe as well as anti-HBs (> 100 IU/L) were also detectable.

TaqMan HBV PCR of WHO standard plasma in concentrations of 102.5, 102, 101.5, 101, and 100.5 IU HBV DNA per milliliter (n = 24 each).

CT = threshold cycle, **P < .01, *P < .05. Typical box plots are shown with median, 25th/75th, and 10th/90th percentiles; the open circles show the 5th/95th percentiles.

TaqMan HBV PCR of WHO standard plasma in concentrations of 102.5, 102, 101.5, 101, and 100.5 IU HBV DNA per milliliter (n = 24 each).

CT = threshold cycle, **P < .01, *P < .05. Typical box plots are shown with median, 25th/75th, and 10th/90th percentiles; the open circles show the 5th/95th percentiles.

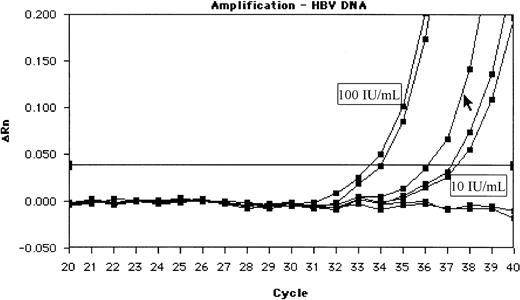

Quantification of HBV DNA showed low levels below 1000 IU/mL for HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative samples as well (Figure2). Even 6 of the 14 HBsAg-positive and HBV DNA–positive samples were quantified to be below 100 IU/mL. The data of HBV DNA quantification in comparison with the anti-HBs levels of the 3 HBsAg-negative samples did not show the reverse correlation (r = 0.03, P = .998), which might have been expected. In Figure 3, an example of an amplification plot of 1 of the 3 HBsAg-negative samples is given to illustrate the unambiguous positive result.

Quantification of HBV DNA–positive samples.

The quantification was carried out by means of a standard curve derived from the validation experiments shown in Figure 1. For the 3 HBsAg-negative samples, the corresponding anti-HBs levels are given.

Quantification of HBV DNA–positive samples.

The quantification was carried out by means of a standard curve derived from the validation experiments shown in Figure 1. For the 3 HBsAg-negative samples, the corresponding anti-HBs levels are given.

Amplification plot of 1 of the 3 HBsAg-negative and HBV DNA–positive samples (cursor) between the standard dilutions of 100 and 10 IU/mL.

This is a screen shot of the original experiment. The relative fluorescence units (ΔRn) of the HBV reporter dye are shown in the course of cycles 20 to 40.

Amplification plot of 1 of the 3 HBsAg-negative and HBV DNA–positive samples (cursor) between the standard dilutions of 100 and 10 IU/mL.

This is a screen shot of the original experiment. The relative fluorescence units (ΔRn) of the HBV reporter dye are shown in the course of cycles 20 to 40.

Discussion

The prevalence of anti-HBc in our first-time blood donor population was markedly lower than that recently described (8.71%) for an adult German population.33 This finding may have been due to the blood donor selection prior to testing, to our criteria that called for reactivity in 2 different anti-HBc assays, and to regional differences in the prevalence of HBV infection between Northern and Southern Germany. However, this also means that routine anti-HBc screening of blood donations would lead to a lower loss of blood donors or, rather, blood donations, than expected. High frequencies of HBV DNA findings have been described at 10% to 15% in “anti-HBc alone”–positive sera.34 This serologic constellation has also been reported to be associated with posttransfusion HBV infection.22-24,35 Thus, 2 recent studies from Greece and Japan tested HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc–positive blood donors with “low-titered” anti-HBs for HBV DNA but not all anti-HBc–positive donors.36,37 In our study, only 12 (5.56%) of all anti-HBc–positive samples tested “anti-HBC alone”–positive after supplementary testing using a second ELISA, and none of these samples were positive for HBV DNA. On the contrary, our 3 HBsAg-negative but viremic blood donors were positive for anti-HBe and anti-HBs as well. However, this serologic constellation was the most frequent in 144 (66.67%) of the anti-HBc–positive blood donors. Thus, our results are concordant with other findings of HBV DNA after complete serologic recovery from acute HBV infection.1,2,4-8,10,11 The results of HBV DNA quantification showed very low levels of viremia in the 3 HBsAg-negative blood donors as well as in the HBsAg-positive donors. We could not find any reverse correlation between the levels of HBV DNA and anti-HBs on the 3 HBsAg-negative, HBV DNA–positive samples. This fact might have been expected if we allege that HBV DNA load corresponds to intact virus particles, which would form immune complexes together with anti-HBs. The sensitivity of our TaqMan HBV PCR after the enrichment of total nucleic acids from 1 or 2 mL plasma by means of the NucliSens Extractor was acceptable. It seems likely that we would have found even more HBV DNA–positive blood donors after investigating the nucleic acids of larger quantities of plasma. The transmission of HBV via liver allografts from donors after complete serologic recovery from HBV infection has been widely documented.38-44 Only the question regarding the infectivity and the infectious dose of such blood donations remains. The inoculation of small amounts of serum and lymphocytes from 3 patients who were HBsAg-negative, anti-HBs–positive, anti-HBc–positive, and HBV DNA–positive into 3 chimpanzees did not lead to infections in any of the animals.45 However, the authors of this study admitted that the amounts of serum or lymphocytes may have been lower than the infectious dose required for such inoculations. To determine the rate of HBV transmissions via anti-HBc–positive and HBsAg–negative blood donations, retrospective studies on regular blood donors and their respective recipients are necessary. Routine anti-HBc screening of blood donations could probably prevent some transfusion-transmitted HBV infections. In an alternative scenario, routine HBV DNA screening of blood donations would not be suitable during this phase of serologically recovered HBV infection, because the low levels of HBV DNA would require tests from large volumes of plasma from the single blood donation. However, in the early window period until HBsAg becomes detectable, NAT using minipools of up to 25 blood donations has been suggested to be effective.46 It would also be of interest to see whether the detection of HBV RNA transcripts, which has been demonstrated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells as well as from plasma specimens, might be of diagnostic value for screening blood donations.47 48

The authors thank Diana Sander, Andrea Reimer, Petra Glessing, Kirsten Jacobsen, Tanja Quandt, Jessica Brodzinski, and Ulla Thiessen for their excellent technical assistance. Thanks are also due to Una Doherty and Dr J. Keogh for assisting us in editing the English form of this manuscript.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 31, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0798.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Holger Hennig, Institute of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, University of Lübeck, Ratzeburger Allee 160, 23538 Lübeck, Germany; e-mail: hennig@immu.mu-luebeck.de.