Abstract

The chimeric monoclonal antibody cAC10, directed against CD30, induces growth arrest of CD30+ cell lines in vitro and has pronounced antitumor activity in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse xenograft models of Hodgkin disease. We have significantly enhanced these activities by conjugating to cAC10 the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) to create the antibody-drug conjugate cAC10-vcMMAE. MMAE, a derivative of the cytotoxic tubulin modifier auristatin E, was covalently coupled to cAC10 through a valine-citrulline peptide linker. The drug was stably attached to the antibody, showing only a 2% release of MMAE following 10-day incubation in human plasma, but it was readily cleaved by lysosomal proteases after receptor-mediated internalization. Release of MMAE into the cytosol induced G2/M-phase growth arrest and cell death through the induction of apoptosis. In vitro, cAC10-vcMMAE was highly potent and selective against CD30+ tumor lines (IC50 less than 10 ng/mL) but was more than 300-fold less active on antigen-negative cells. In SCID mouse xenograft models of anaplastic large cell lymphoma or Hodgkin disease, cAC10-vcMMAE was efficacious at doses as low as 1 mg/kg. Mice treated at 30 mg/kg cAC10-vcMMAE showed no signs of toxicity. These data indicate that cAC10-vcMMAE may be a highly effective and selective therapy for the treatment of CD30+ neoplasias.

Introduction

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family member CD30 is a primary diagnostic marker of Hodgkin disease (HD) and is highly expressed on the cell surfaces of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and a subset of non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1,2 CD30 expression is not detectable on healthy tissues outside the immune system or on resting lymphocytes and monocytes.3 Expression is induced on T- and B-cell activation. High levels of CD30 are expressed on activated, infiltrating lymphocytes in chronic autoimmune or inflammatory disease, and some portion of this is shed into the circulation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,4 systemic sclerosis,5 and multiple sclerosis.6 The restricted expression profile of CD30, with high levels on specific cancers and limited expression on healthy tissues, makes this an ideal target for antibody-directed therapies. Its high expression on chronically activated lymphocytes also suggests a potential for CD30-targeted therapies in immunologic diseases.

Prior efforts to treat HD clinically with the anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody (mAb) BerH2, though not efficacious, demonstrated that mAbs directed against CD30 effectively target malignant cells.7 In a subsequent clinical trial, a conjugate of BerH2 to the plant toxin saporin produced transient reductions in tumor mass that, though not durable, established the ability of an anti-CD30 toxin conjugate to target and internalize into tumor cells on CD30 binding.8 Additional studies continue to evaluate the potential efficacy of anti-CD30 antibody-toxin conjugates and fusion proteins.9,10 Although protein-toxin–linked mAb therapies are highly potent in model systems, they are hampered by the generation of neutralizing antibodies after the initial course of treatment.11

We have previously described the chimeric mAb, cAC10 (SGN-30), with unique activities against HD.12 Although other anti-CD30 mAbs have been shown to have antitumor activity against ALCL,13 cAC10 had potent activity in vitro and in vivo against HD and ALCL. In vitro, cross-linked cAC10 inhibited the growth of a variety of HD and ALCL cell lines, with at least some of the activity attributed to the induction of apoptosis. In severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse xenograft models of disseminated and subcutaneous HD, cAC10 provided a significant survival advantage over untreated animals in a dose-dependent manner. cAC10 (SGN-30) is under evaluation in clinical trials for the treatment of CD30-expressing hematologic malignancies.

The therapeutic potential of unmodified mAbs for the treatment of cancer has been demonstrated in preclinical and, more recently, clinical settings. The anti-CD20 mAb rituximab, for example, is highly effective as a monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy.14 Nonetheless, there are significant efforts to improve on its antitumor activity, and recent studies15 have shown that a radiolabeled mAb against CD20 (ibritumomab tiuxetan) can be effective against rituximab-refractory tumors.

To enhance the potency of CD30-targeted mAb therapy, we have generated an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), cAC10-vcMMAE, consisting of the chimeric mAb chemically conjugated to monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). MMAE, a synthetic analog of the natural product dolastatin 10,16 was conjugated to cAC10 with a highly stable peptide linker that is selectively cleaved by lysosomal enzymes after internalization.17 cAC10-vcMMAE is stable under physiologic conditions but specifically binds to, internalizes, and is cytotoxic against CD30-expressing cell lines in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

cAC10 was produced as previously described.12 CD30+ HD lines L540, KM-H2, HDLM-2, and L428 and the ALCL line Karpas 299 were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganism und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). L540cy, a derivative of the HD line L540 adapted to xenograft growth, was provided by Dr Phil Thorpe (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas). Raji, Ramos, and Daudi Burkitt lymphoma lines were from The American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Goat-antimouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and goat-antihuman FITC were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Anti-CD30 mAb Ki-1 was from Accurate Chemicals (Westbury, NY). cBR96, a human chimeric IgG1κ (Seattle Genetics) was used as a chimeric, isotype-matched control. Fresh human plasma was obtained from AllCells (Berkeley, CA).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis

To compare relative levels of CD30 on different tumor cells, 1 × 106 cells were combined with a saturating level (10 μg/mL) of cAC10 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes on ice and washed twice with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound mAb. Cells were then stained with secondary goat-antihuman immunoglobulin G (IgG) FITC, again at saturating levels (10 μg/mL) in ice-cold PBS, incubated for 30 minutes on ice, and washed with PBS. Labeled cells were examined by flow cytometry on a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer and were gated to exclude nonviable cells. Data were analyzed using Winlist 4.0 software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME), and the background-corrected mean fluorescence intensity was determined for each cell type.

To compare the saturation binding of mAb and ADC, 5 × 105 Karpas 299 ALCL cells were combined with serial dilutions of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or corresponding isotype-matched controls in staining media for 30 minutes on ice and washed twice with ice-cold staining medium. Cells were then incubated with goat-antihuman IgG FITC at 10 μg/mL on ice for 30 minutes and washed with PBS. Labeled cells were then run on the flow cytometer and analyzed as above. For mAb saturation binding, 3 × 105 Karpas 299 cells were combined with increasing concentrations of cAC10 or cAC10-ADCs diluted in ice-cold staining media for 20 minutes on ice, washed twice with ice-cold staining media to remove free mAb, and incubated with 1:50 goat-antihuman FITC. Labeled cells were washed and analyzed as described above. Resultant mean fluorescence intensities were plotted versus mAb concentration.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity was measured using Alamar Blue (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) dye reduction assay as previously described, according to the manufacturer's directions.18 Briefly, a 40% solution (wt/vol) of Alamar Blue was freshly prepared in complete media just before cultures were added. Ninety-two hours after drug exposure, Alamar Blue solution was added to cells to constitute 10% culture volume. Cells were incubated for 4 hours, and dye reduction was measured on a Fusion HT fluorescent plate reader (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT).

Drug synthesis

Synthesis of the activated valine-citrulline linker used in these studies was modified from the previously described procedure.17,19 The synthesis of auristatin E has been previously described.16,20 Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) was prepared by replacing a protected form of monomethylvaline for N,N-dimethylvaline in the synthesis of auristatin E.20 MMAE was further modified with the valine-citrulline linker for conjugation to mAbs. Specifically, MMAE was modified with activated derivatives of maleimidocaproyl-valine-citrulline containing a p-aminobenzylcarbamate spacer between the MMAE and the linker.

The activated linker (60 mg, 84 μmol, 1.1 equivalents), MMAE (56 mg, 76 μmol, 1.0 equivalents), and HOBt (10 mg, 1.0 equivalents) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF (dimethylformamide; 2 mL) and pyridine (0.5 mL). The contents were stirred during monitoring with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The reaction mixture was directly injected onto a reverse-phase preparative-HPLC column (Synergi MAX-RP; C12 column 21.2 mm × 25 cm, 10 μ, 80 Å, using a gradient run of MeCN and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid [TFA] at 25 mL/min from 10% to 100% over 40 minutes followed by 100% MeCN for 20 minutes). Fractions were immediately analyzed, pooled, and concentrated to a pale yellow solid. The addition of methylene chloride and hexanes (1:1) followed by evaporation led to the production of vcMMAE as an off-white powder. Data were as follows: yield, 72 mg (70%); Rf, 0.36 (9:1 CH2Cl2-MeOH); ES-MS m/z, 1316.7 [M+H]+; 1334.4 [M+NH4]+; UVλmax 215, 248 nm.

Conjugate preparation

Partial mAb reduction for conjugation purposes was as previously described.17 To 4.8 mL cAC10 (10 mg/mL) was added 600 μL of 500 mM sodium borate/500 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, followed by 600 μL of 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in water. After incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes, the buffer was exchanged by elution through Sephadex G-25 resin with PBS containing 1 mM diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA; Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI). The thiol-antibody value was determined from the reduced mAb concentration determined from 280-nm absorbance, and the thiol concentration was determined by reaction with DTNB (5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid); Aldrich) and absorbance measured at 412 nm.

PBS containing 1 mM DTPA (PBS/D) was added to the reduced antibody to make the antibody concentration 2.5 mg/mL in the final reaction mixture, and the solution was chilled. The drug-linker solution to be used in the conjugation was prepared by diluting drug-linker from a frozen dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) stock solution at a known concentration (approximately 10 mM) in sufficient acetonitrile to make the conjugation reaction mixture 20% organic/80% aqueous, and the solution was chilled on ice. The volume of drug-linker stock solution was calculated to contain 9.5-mol drug-linker/1 mol antibody. The drug-linker solution was added rapidly with mixing to the cold-reduced antibody solution, and the mixture was left on ice for 1 hour. A 20-fold excess of cysteine over maleimide was then added from a freshly prepared 100-mM solution in PBS/D to quench the conjugation reaction. While the temperature was maintained at 4°C, the reaction mixture was concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration and buffer-exchanged by elution through Sephadex G25 equilibrated in PBS. The conjugate was then filtered through a 0.2-μm filter under sterile conditions and stored at –80°C for analysis and testing. ADCs were analyzed for concentration by UV absorbance, aggregation by size-exclusion chromatography, drug/antibody by measuring unreacted thiols with DTNB, and residual free drug by reverse-phase HPLC. All mAbs and ADCs used in these studies exceeded 98% monomeric protein. Drug/mAb ratios were calculated to be 8:1 for cAC10-vcMMAE and 8:1 for control cIgG-vcMMAE.

Stability analysis by LC/MS

cAC10-vcMMAE was incubated in normal mouse, human, or dog plasma containing heparin (Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Indianapolis, IN) at 0.327 mg/mL. Using a 1:32.7 ratio for MMAE/mAb linker (MMAE Mr, 718; cAC10-vcMMAE Mr, 164 300) and 8 drug-antibody loading, the calculated maximum MMAE concentration was 10 μg/mL. Triplicate samples were incubated at 37°C, and 50-μL aliquots were taken at 0, 1, 2, 4, 7, and 10 days and stored at –80°C. Calibration standards were prepared using free MMAE in each plasma type. Sample aliquots were spiked with 10 μL of a 1 μg/mL internal standard (MMAE appended with 2 methyl groups) followed by the addition of 2.9 M phosphoric acid (10 μL) to disrupt nonspecific protein binding. Samples were applied to an Oasis MCX extraction cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) on a vacuum manifold. The cartridge was washed with 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (500 μL) followed by methanol (500 μL) and eluted with 5% ammonium hydroxide in methanol (500 μL). The eluate was collected, dried under vacuum, and reconstituted in 100 μL of 25% acetonitrile in water using sonication to aid in solvation. Samples were analyzed using LCMS/MS as follows: 1100 HPLC (Agilent, Wilmington, DE); Xterra MS C18 2.5-mm 4.6 × 30-mm column (Waters); solvent A, 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.0); solvent B, acetonitrile; the gradient was 5% to 95% acetonitrile in 30-second holding at 95% for 1 minute followed by a 1.5-minute equilibration; 1 mL/min flow rate split to 0.1 mL/min before the MS source; LCQ DECA XP ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA); atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source with capillary voltage at 3.0 V, capillary temperature at 200°C, vaporizer temperature at 350°C, sheath gas flow rate 70 arb, and entrance lens voltage of – 84 V. Mass spectrometer conditions were optimized for maximum sensitivity of the protonated molecular species (MH+) of MMAE at m/z 718.5 and internal standard at m/z 746.5. Daughter ions used for quantitation were m/z 686.5 and 506.4 for MMAE and m/z 714.5 for the internal standard.

Xenograft models of human Hodgkin disease

For localized, subcutaneous disease models of ALCL and HD, 5 × 106 Karpas 299 or 2 × 107 L540cy cells, respectively, were implanted into the right flanks of C.B.-17/IcrHsd-SCID mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Therapy with cAC10-vcMMAE or controls was initiated when the tumor size in each group of 5 animals averaged approximately 100 mm3. Treatment consisted of intravenous injections every fourth day for 4 injections (q4d × 4). Tumor volume was determined using the formula (L × W2)/2. For the disseminated ALCL model, 1 × 106 Karpas 299 cells were injected through the tail vein into C.B.-17 SCID mice. Treatment was initiated 9 or 13 days after tumor injection and was administered intravenously on a schedule of q4d × 4. Animals were evaluated for signs of disseminated disease, in particular hindlimb paralysis. Mice that developed these or other significant signs of disease were then killed in accordance with Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Results

Preparation of antibody-drug conjugates

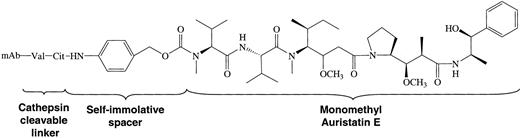

Auristatins are highly potent antimitotic agents related in structure to the marine natural product, dolastatin 10. These agents act by inhibiting the polymerization of tubulin in dividing cells.16,20 Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) was prepared by replacing a protected form of monomethylvaline for the amino-terminal valine in the synthesis of auristatin E.20 MMAE was then further modified with maleimidocaproyl-valine-citrulline to result in vcMMAE, which contained a p-aminobenzylcarbamate spacer between the MMAE and the linker. The resultant ADC used in these studies is shown in Figure 1.

Structure of the cAC10-vcMMAE system. Conjugates were prepared by controlled partial reduction of internal cAC10 disulfides with DTT, followed by addition of the maleimide-vc-linker-MMAE. Stable thioether-linked ADCs were formed with the addition of the free sulfhydryl groups on the mAbs to the maleimides present on the drugs. cAC10-vcMMAE and the cIgG-vcMMAE used in these studies contained approximately 8 drugs/mAb.

Structure of the cAC10-vcMMAE system. Conjugates were prepared by controlled partial reduction of internal cAC10 disulfides with DTT, followed by addition of the maleimide-vc-linker-MMAE. Stable thioether-linked ADCs were formed with the addition of the free sulfhydryl groups on the mAbs to the maleimides present on the drugs. cAC10-vcMMAE and the cIgG-vcMMAE used in these studies contained approximately 8 drugs/mAb.

Binding of cAC10 and cAC10-vcMMAE to CD30+ cells

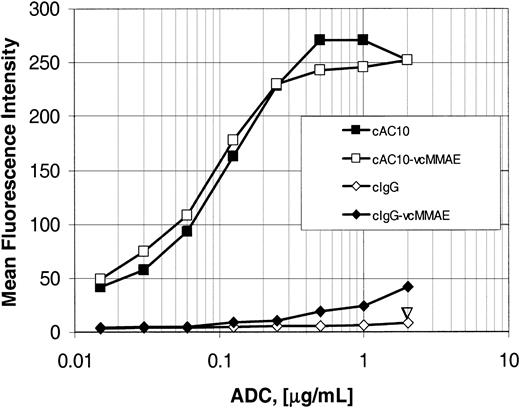

The mAb AC10 was originally produced by immunizing mice with the CD30+ large granular lymphoma cell line YT and was shown to be specific for CD30.21 Construction and characterization of the chimeric mAb cAC10, with the scaffold of human IgG gamma 1 and kappa constant regions and the determination of relative binding of cAC10 and the parental murine mAb AC10 to cell lines used in this study, has been previously described.12 After conjugation of cAC10 or control cIgG to vcMMAE, titrations of the mAb and ADC were compared for their relative abilities to bind CD30+ Karpas 299 cells as detected using goat-antihuman FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Figure 2). The binding of cAC10-vcMMAE to Karpas 299 cells was comparable to that of the parental mAb cAC10, with both the mAb and ADC showing the same dose response and saturating at approximately 1 μg/mL. These results indicated that conjugation did not diminish cAC10-specific binding to cell surface CD30. Equally important, the drug-linker vcMMAE did not impart nonspecific binding to the cells when coupled to irrelevant, isotype-matched chimeric IgG (cIgG-vcMMAE). Consistent with this, in control studies cAC10-vcMMAE did not bind to CD30– cells (data not shown).

Antibody and ADC saturation binding. Binding of cAC10, irrelevant cIgG, and their respective ADCs to CD30+ Karpas 299 cells. Cells were combined with increasing concentrations of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, an irrelevant isotype-matched IgG, or this IgG linked to vcMMAE. Cells were incubated for 20 minutes, washed with 2% FBS/PBS (staining medium) to remove free mAb, and incubated with goat-antihuman-FITC. Labeled cells were washed again with staining medium and examined by flow cytometry. The resultant mean fluorescence intensities were plotted versus mAb concentration, as described in “Materials and methods.”

Antibody and ADC saturation binding. Binding of cAC10, irrelevant cIgG, and their respective ADCs to CD30+ Karpas 299 cells. Cells were combined with increasing concentrations of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, an irrelevant isotype-matched IgG, or this IgG linked to vcMMAE. Cells were incubated for 20 minutes, washed with 2% FBS/PBS (staining medium) to remove free mAb, and incubated with goat-antihuman-FITC. Labeled cells were washed again with staining medium and examined by flow cytometry. The resultant mean fluorescence intensities were plotted versus mAb concentration, as described in “Materials and methods.”

In vitro potency and selectivity of cAC10-vcMMAE

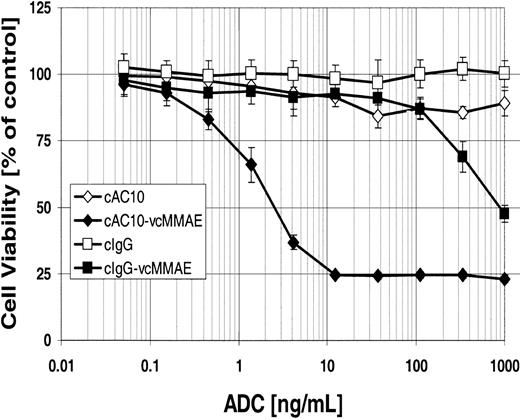

Others have demonstrated the antiproliferative effects of immobilized anti-CD30 mAbs on ALCL cell lines,22,23 and we have previously shown that the mAb cAC10, when cross-linked by a secondary mAb, has antiproliferative effects lower than 1 μg/mL and can induce apoptosis greater than 1 μg/mL on HD and ALCL lines in vitro.12 To evaluate the in vitro cytotoxicity of cAC10-vcMMAE, CD30+ Karpas 299 cells were exposed to either cAC10-vcMMAE, the parental mAb cAC10, an isotype-matched irrelevant control IgG, or control IgG conjugated with vcMMAE. After 96 hours of continuous exposure to the conjugates, cytotoxicity was assessed by Alamar Blue assay as described in “Materials and methods.” Figure 3 shows that cAC10-vcMMAE was potently cytotoxic to Karpas 299 cells, with an IC50 value (defined as the mAb concentration that gave 50% cell kill) of 2.5 ng/mL. In contrast, the IC50 of the control ADC was 850 ng/mL; thus, the nonbinding control ADC was 340-fold less cytotoxic than cAC10-vcMMAE. Under these conditions unmodified mAb cAC10, without secondary cross-linking, had little effect on cytotoxicity, giving only 18% cell kill at 1 μg/mL.

In vitro cytotoxicity and selectivity of cAC10-vcMMAE. CD30+ Karpas 299 cells were plated at 5000 cells/well and were exposed to a graded titration of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or an isotype-matched irrelevant control immunoglobulin or its conjugate with vcMMAE. Cells were assessed for cytotoxicity by Alamar Blue assay after 96 hours of continuous exposure, as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage viability, relative to untreated control wells, was plotted versus ADC concentration. Results for each study are the average of quadruplicate determinations. Error bars indicate ± SD.

In vitro cytotoxicity and selectivity of cAC10-vcMMAE. CD30+ Karpas 299 cells were plated at 5000 cells/well and were exposed to a graded titration of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or an isotype-matched irrelevant control immunoglobulin or its conjugate with vcMMAE. Cells were assessed for cytotoxicity by Alamar Blue assay after 96 hours of continuous exposure, as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage viability, relative to untreated control wells, was plotted versus ADC concentration. Results for each study are the average of quadruplicate determinations. Error bars indicate ± SD.

The cytotoxicity and selectivity of cAC10-vcMMAE was further evaluated on a panel of antigen-positive and antigen-negative cell lines. The relative density of CD30 antigen on the various lines was evaluated by comparing the fluorescence signal of cAC10 with that of a control mAb (Table 1). Cells with a binding ratio of 2 or less were considered negative for CD30 expression. Three of the antigen-positive cell lines were sensitive to cAC10-vcMMAE cytotoxicity, with IC50 values less than 10 ng/mL (range, 0.5-9.9 ng/mL). The T-cell–like HD line HDLM2, though CD30+, showed reduced sensitivity to the ADC (IC50, 302 ng/mL). Because this line is sensitive to the free drug, the efficiency of MMAE delivery by the ADC may not be equivalent in all antigen-positive cells. In contrast to CD30+ cells, the antigen-negative lines were insensitive to cAC10-vcMMAE, with IC50 values greater than 3000 ng/mL. All cell lines tested were highly sensitive to free MMAE, with IC50 values less than 0.3 nM, suggesting that selective sensitivity was conferred by the ADCs. Despite growth-inhibitory activity by cross-linked mAb cAC10,12 none of the lines tested showed more than 20% cytotoxicity to cAC10 alone at concentrations up to 1 μg/mL (data not shown).

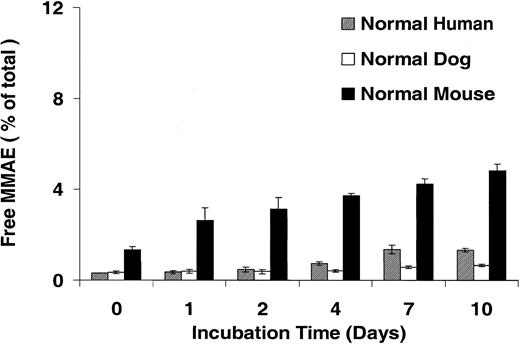

In vitro stability of cAC10-vcMMAE

Our data demonstrate that the cytotoxicity of cAC10-vcMMAE was selective because the nonbinding control ADC had a nominal effect on CD30+ cells and cAC10-vcMMAE was comparably noncytotoxic on CD30– cells. These data suggest MMAE remained attenuated and stably linked to the antibody outside the tumor cell for the duration of the 4-day, continuous-exposure assay. The high potency of the free drug and the expected long half-life of an antibody in vivo necessitate that the linkage remain intact and the drug remain attenuated in circulation for an extended period of time. To further evaluate the stability of the valine-citrulline linkage, cAC10-vcMMAE at 327 μg/mL (containing 10 μg/mL MMAE) was incubated in human, mouse, or dog plasma at 37°C for a period of 10 days. Aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and analyzed by LC/MS/MS for the release of free drug as described in “Materials and methods.” Figure 4 shows that in human and dog plasma, less than 2% of the total drug was released after 10 days. In mouse plasma, less than 5% of the total drug was released during this time. A subsequent qualitative full-scan LC/MS analysis, including UV detection, of the same samples did not reveal the presence of other molecular species identifiable as drug or drug-linker degradation products (data not shown). Incubation of free MMAE in these 3 plasma samples also showed no degradation over the same time period, further demonstrating stability of the free drug in human plasma once cleaved from the mAb (data not shown).

Stability of cAC10-vcMMAE drug linkage in plasma. cAC10-vcMMAE at 0.327 mg/mL (containing 10 μg/mL MMAE) was incubated in human, mouse, or dog plasma at 37°C over a period of 10 days. Aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and analyzed by LCMS/MS for free drug, as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage released free drug relative to an experimental maximum was plotted versus the incubation time in days. Error bars indicate ± SD.

Stability of cAC10-vcMMAE drug linkage in plasma. cAC10-vcMMAE at 0.327 mg/mL (containing 10 μg/mL MMAE) was incubated in human, mouse, or dog plasma at 37°C over a period of 10 days. Aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and analyzed by LCMS/MS for free drug, as described in “Materials and methods.” The percentage released free drug relative to an experimental maximum was plotted versus the incubation time in days. Error bars indicate ± SD.

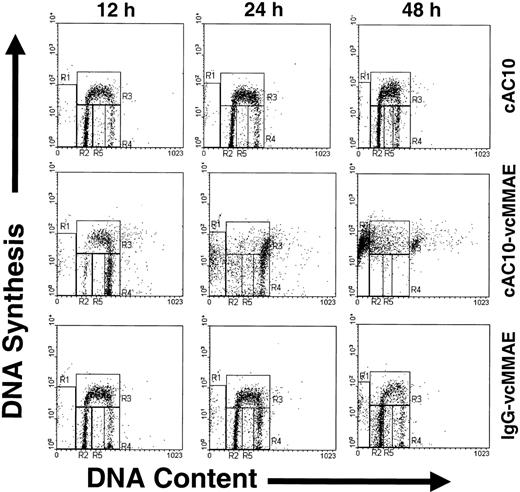

Cell cycle effects of cAC10-vcMMAE

To examine the cell cycle and apoptotic effects of cAC10-vcMMAE, CD30+ L540 cells were cultured in complete media containing a saturating level (1 μg/mL) of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or an isotype-matched, irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE. At 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure, cells were labeled with bromodeoxyuridine for 30 minutes to detect nascent DNA synthesis and with propidium iodide to detect total DNA content. Labeled cells were then analyzed for active DNA synthesis and cell cycle position at the time of harvest by flow cytometry. The resultant histograms of cells after treatment are shown in Figure 5. The specific regions shown in Figure 5 were quantified, along with those of untreated cells (not shown), and the percentage of the total population found in each region is shown in Table 2. Treatment with cAC10 or irrelevant ADC at 1 μg/mL showed no significant difference in cell cycle position or DNA fragmentation compared with untreated control cells (Table 2). In contrast to cells treated with 1 μg/mL irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE, cells exposed to an equal level of cAC10-vcMMAE showed a significant increase in G2 cells, as determined by DNA content, and coincident loss of G1 cells within 12 hours of exposure; the effects were consistent with a rapid G2/M-phase arrest induced by MMAE. The G1 population reached minimum levels within 12 hours of exposure. Coincident with this, G2 cells rose from 10% in untreated cells to 47% at 12 hours after cAC10-vcMMAE exposure. At 24 hours after exposure, the G2 population became highly diffuse, with sub-G2 and sub-G1 DNA content becoming evident. By 48 hours, 53% of the cells showed sub-G1 DNA content, consistent with apoptotic DNA fragmentation (Table 2). These data, representative of 3 independent studies, suggest that cAC10-vcMMAE selectively induced growth arrest in G2/M phase followed by apoptotic cell death and that this effect was not seen after sustained exposure to equivalently high concentrations of control IgG-vcMMAE.

Effects of cAC10-vcMMAE on cell cycle and apoptosis. CD30+, L540 cells were cultured in complete media containing a saturating level (1 μg/mL) of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or an isotype-matched irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE. At 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure, cells were labeled with bromodeoxyuridine for 30 minutes to detect nascent DNA synthesis and with propidium iodine to detect total DNA content, and they were analyzed for active DNA synthesis and cell cycle position at the time of harvest by flow cytometry. Quadrants R2 to R4 correspond to G1, S-phase, and G2/M-phase cells, respectively. R1 and R5 correspond to sub-G1 fragmented DNA typical of apoptotic cells.

Effects of cAC10-vcMMAE on cell cycle and apoptosis. CD30+, L540 cells were cultured in complete media containing a saturating level (1 μg/mL) of cAC10, cAC10-vcMMAE, or an isotype-matched irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE. At 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure, cells were labeled with bromodeoxyuridine for 30 minutes to detect nascent DNA synthesis and with propidium iodine to detect total DNA content, and they were analyzed for active DNA synthesis and cell cycle position at the time of harvest by flow cytometry. Quadrants R2 to R4 correspond to G1, S-phase, and G2/M-phase cells, respectively. R1 and R5 correspond to sub-G1 fragmented DNA typical of apoptotic cells.

In vivo toxicity of cAC10-vcMMAE

In previous studies the antibody component of cAC10-vcMMAE was tested in SCID mice at doses up to 100 mg/kg without any signs of toxicity.12 The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in mice of dolastatin 10, a cytotoxic molecule similar in structure to MMAE,16 was approximately 0.45 mg/kg,24 and we found the MTD of free MMAE in SCID mice to be between 0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg. To determine the single-dose MTD, cAC10-vcMMAE was injected into SCID mice through the tail vein at doses ranging from 10 to 120 mg/kg. After injection, general appearance and body weight were monitored for 3 weeks. Doses of cAC10-vcMMAE up to 30 mg/kg were well tolerated with no apparent toxicity. At 40 mg/kg, the mice experienced weight loss of up to 20% within 4 days of injection, at which point 3 of 5 animals were killed. The surviving mice began to regain weight 7 to 10 days after injection and returned to initial body weight by day 16. Doses higher than 40 mg/kg were lethal. Thus, the MTD of cAC10-vcMMAE in SCID mice was determined to be between 30 and 40 mg/kg. Similar sensitivity was seen in immunocompetent Balb/c mice. cAC10-vcMMAE dosed at 30 mg/kg contains approximately 1.1 mg/kg of the drug component MMAE.

Antitumor activity of cAC10-vcMMAE in vivo

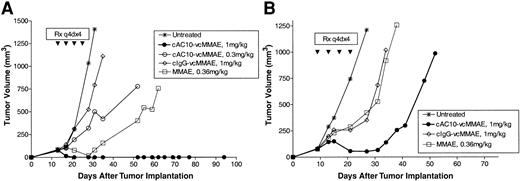

The efficacy of cAC10-vcMMAE was subsequently evaluated in subcutaneous xenograft models of ALCL and HD tumors in SCID mice. Karpas 299 (ALCL) or L540cy (HD) cells were implanted into the flanks of SCID mice, and tumors were allowed to develop until the average tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3. Tumor-bearing mice were then randomly divided into treatment groups and were left untreated or were treated with cAC10-vcMMAE, an isotype-matched control ADC, or with free MMAE at 10 × the molar equivalent carried by the ADCs. Therapy was administered every 4 days for a total of 4 doses (q4d × 4). Left untreated, tumors grew rapidly and reached 1000 mm3 within 25 to 30 days.

In the Karpas 299 ALCL model, 1 mg/kg cAC10-vcMMAE induced complete, durable tumor regression in all animals (Figure 6A). Antitumor activity was dependent on dose—cAC10-vcMMAE at 0.3 mg/kg provided less effective therapy than the 1 mg/kg dose. At this reduced dose, 1 of 5 animals experienced complete tumor regression that was durable for the course of the study. Administration of control IgG-vcMMAE at 1 mg/kg had no impact on tumor growth, indicating that the observed therapeutic responses were specific for the CD30-targeted drug. cAC10-vcMMAE also had significant activity against L540cy tumors in SCID mice. In this HD model, partial tumor regressions were observed in all mice receiving cAC10-vcMMAE at 1 mg/kg, whereas little to no activity was seen with comparable treatment with control ADC or 10 × the molar equivalent of free MMAE (Figure 6B). These data are representative findings of a minimum of 3 independent studies demonstrating comparable antitumor activity with cAC10-vcMMAE. In contrast to the activity of cAC10-vcMMAE, the anti-CD30 antibody component showed significantly less activity than the ADC in these subcutaneous models. We have previously shown that a comparable dose of 1 mg/kg of the unmodified cAC10 affected only slight tumor growth delay against HD xenografts.12 In multiple studies against Karpas-299 ALCL tumor xenografts, neither the unmodified mAb at 1 mg/kg, nor the unmodified mAb at 1 mg/kg plus free MMAE at 10 × the drug level delivered by 1 mg/kg cAC10-vcMMAE produced detectable antitumor activity (data not shown).

Efficacy of cAC10-vcMMAE in HD and ALCL models. Antitumor activity of cAC10-vcMMAE on subcutaneous Karpas 299 and L540cy HD tumor models in SCID mice. Mice were implanted with 5 × 106 Karpas 299 ALCL cells (A) or 2 × 107 L540cy Hodgkin disease cells (B) into the right flank. Groups of mice (5/group) were left untreated (x) or received cAC10-vcMMAE at 0.3 mg/kg (○) or 1 mg/mg (•), an irrelevant IgG-vcMMAE at 1 mg/kg (⋄), or free MMAE at 0.36 mg/kg (□) (10 × the dose equivalent of 1 mg/kg ADC) on a schedule of q4d × 4 starting when the tumor size in each group of 5 animals averaged approximately 100 mm3.

Efficacy of cAC10-vcMMAE in HD and ALCL models. Antitumor activity of cAC10-vcMMAE on subcutaneous Karpas 299 and L540cy HD tumor models in SCID mice. Mice were implanted with 5 × 106 Karpas 299 ALCL cells (A) or 2 × 107 L540cy Hodgkin disease cells (B) into the right flank. Groups of mice (5/group) were left untreated (x) or received cAC10-vcMMAE at 0.3 mg/kg (○) or 1 mg/mg (•), an irrelevant IgG-vcMMAE at 1 mg/kg (⋄), or free MMAE at 0.36 mg/kg (□) (10 × the dose equivalent of 1 mg/kg ADC) on a schedule of q4d × 4 starting when the tumor size in each group of 5 animals averaged approximately 100 mm3.

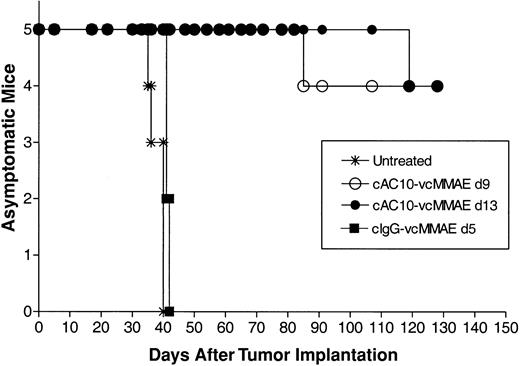

The antitumor activity of cAC10-vcMMAE was also evaluated in a disseminated model of ALCL. Karpas 299 cells were injected into the tail veins of SCID mice on day 0, and the mice were divided into treatment groups. Left untreated, tumor cell proliferation produces a variety of disease symptoms, including head and neck tumors and paralysis.13 All untreated mice showed signs of severe disease within 40 days, at which point they were killed (Figure 7). To ensure evaluation against well-established tumors, therapy with cAC10-vcMMAE was delayed until either 9 or 13 days after tumor cell injection, using a q4d × 4 schedule at 1 mg/kg per dose. An additional group of mice received the nonbinding control ADC, at the same dose and schedule, starting on day 5. In both groups treated with cAC10-vcMMAE, starting either on day 9 or day 13 after tumor implantation, 4 of 5 mice survived for more than 130 days (duration of study) with no apparent signs of disease. The remaining mouse in each of these groups acquired symptoms of disease over the course of the study, yet each still showed distinct survival advantage over untreated mice (Figure 7). Therapy with control IgG-vcMMAE initiated on day 5 provided no antitumor activity. Taken together with toxicity data, cAC10-vcMMAE induced significant antitumor activity in subcutaneous and disseminated tumor models in mice at less than one thirtieth the maximum tolerated dose.

Efficacy of delayed-treatment cAC10-vcMMAE in a disseminated Karpas 299 ALCL tumor model in SCID mice. Mice were implanted with 2 × 107 Karpas 299 ALCL cells into the tail vein. Groups of mice (5/group) were left untreated (*) or received 3 mg/kg of either cAC10-MMAE starting on day 9 (○) or on day 13 (•), or an irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE starting on day 5 after tumor (▪).

Efficacy of delayed-treatment cAC10-vcMMAE in a disseminated Karpas 299 ALCL tumor model in SCID mice. Mice were implanted with 2 × 107 Karpas 299 ALCL cells into the tail vein. Groups of mice (5/group) were left untreated (*) or received 3 mg/kg of either cAC10-MMAE starting on day 9 (○) or on day 13 (•), or an irrelevant cIgG-vcMMAE starting on day 5 after tumor (▪).

Discussion

After many formative years, therapeutic mAbs for the treatment of cancer have recently advanced to become standards of care in some breast cancers and hematologic malignancies.25 Because of its expression profile, the lymphocyte activation marker CD30 is an attractive target for mAb-based therapies. It is highly expressed on the cell surface in Hodgkin disease, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and a subset of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but its expression on healthy cells and tissues is limited to activated T cells and activated B cells.2 We have recently shown that an anti-CD30 mAb, cAC10 (SGN-30), has efficacy against HD in vitro and in vivo.12 SGN-30 has recently entered clinical trials for the treatment of CD30+ malignancies.

In the present work, we have focused on making cAC10 a more potent antitumor agent by conjugating the antibody to a cytotoxic drug, MMAE, through a stable peptide linker to create cAC10-vcMMAE. ADCs provide a method to deliver a chemotherapeutic agent to the surfaces of antigen-positive tumor cells through the targeted mAb. Once bound to the antigen, the ADC is internalized and the drug is released into the intracellular environment, where it affects cell killing. By specifically delivering a chemotherapeutic to the tumor site, but not to antigen-negative normal tissues, the systemic toxicity of the chemotherapeutic agent can be limited while its therapeutic activity is focused on the tumor. In addition, mAb-mediated internalization provides a vehicle of cell entry for molecules that do not efficiently cross the cell membrane. The concept of ADC has been well explored, and one such molecule, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), which targets CD33, has been approved for clinical use for the treatment of AML.26 Other ADCs, including Lewisy-targeted cBR96-doxorubicin and CA242-targeted C242-DM1, among others, have also been extensively evaluated in preclinical studies and clinical trials.27,28

For an ADC to be effective and relatively nontoxic, the chemotherapeutic drug should remain in stable linkage with the mAb while in circulation but should be efficiently released on internalization into the targeted cells. One feature common to most ADC technologies evaluated to date is that antibody-drug coupling is accomplished by way of a hydrazone or disulfide linkage.29,30 Through this approach, the drug is released from the antibody by reduction or acid hydrolysis within lysosomes. Linkage chemistries such as hydrazone have short-stability half-lives that can be significantly less than the expected circulating half-life of the mAb.31 Deficiencies in linkage stability can result in untoward toxicities from the released drug, and these may be especially problematic for ADCs using high-potency drugs such as MMAE and calicheamicin.31 Linkage instability creates an additional therapeutic problem in the eventual masking of tumor antigen with mAb devoid of drug. We have found that protease-cleavable dipeptide linkers such as those used in cAC10-vcMMAE offer a significant stability advantage in this regard,20,32 and we have shown here that cAC10-vcMMAE incubated in human plasma resulted in the release of less than 2% of the drug from the mAb after 10-day incubation at 37°C. By extrapolation, the drug linkage half-life in human plasma is in excess of 250 days, well in excess of that of circulating IgG. Drug loss from the conjugate was increased to approximately 5% at 10 days when the ADC was incubated in mouse plasma, suggesting more protease activity is present in mouse plasma than in human plasma. By comparison, drugs linked to mAbs through acid-cleavable linkers show significantly greater instability, with approximately 50% of drug release within 2 days of incubation in human serum.29,31 The relative insensitivity of antigen-negative cells to cAC10-vcMMAE compared with their sensitivity to free MMAE (Table 1) also supports the concept that nominal free drug was released from the conjugate, even after a prolonged 96-hour incubation.

cAC10-vcMMAE had potent and selective cytotoxic activity. Cells expressing CD30, such as Karpas 299, were sensitive to the ADC at nanogram per milliliter levels, whereas antigen-negative cell lines were approximately 3 orders of magnitude less sensitive. Cytotoxicity was caused, at least in part, by the induction of apoptosis. MMAE is a derivative of the cytotoxic tubulin modifier auristatin E, and cAC10-vcMMAE appears to induce apoptosis by a mechanism similar to that of other tubulin-modifying agents, such as taxanes.33 Within 12 hours of exposure, L540 cells entered growth arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and initiated DNA fragmentation. Although the expression of CD30 was required for cells to be sensitive to cAC10-vcMMAE, there was not a direct correlation between antigen expression level and sensitivity. HDLM-2 cells, with a relatively high level of CD30 (binding ratio, 147), were only moderately sensitive to cAC10-vcMMAE with an IC50 of 302 ng/mL. In contrast, SU-DHL-1 cells had a lower binding ratio but were approximately 1000-fold more sensitive. Because both lines were equally sensitive to free MMAE, other factors, such as rate of internalization, intracellular trafficking of ADC, and enzymatic cleavage and release of MMAE from the lysosome after internalization, must contribute to sensitivity. The role of these factors in the varying tumor cell sensitivity to cAC10-vcMMAE remains to be explored.

One key parameter in considering the clinical potential for cAC10-vcMMAE is its therapeutic window or the ratio of the maximum tolerated dose to the therapeutic dose. Initial toxicity evaluation in mice demonstrated that cAC10-vcMMAE was well tolerated, with no signs of toxicity up to doses of 30 mg/kg. At 40 mg/kg, cAC10-vcMMAE was toxic. Mice experienced weight loss of up to 20% within 3 days, though this toxicity appeared to be reversible. Equally important in establishing the therapeutic window is the therapeutic dose. At doses of 1 mg/kg, cAC10-vcMMAE induced complete and durable regression in subcutaneous and disseminated Karpas-299 ALCL xenografts and displayed significant antitumor activity against subcutaneous HD xenografts. It is significant that 1 mg/kg cAC10-vcMMAE contains 0.036 mg/kg targeted MMAE, a dose roughly equivalent to 5% of the MTD of the free drug alone, further supporting the usefulness of targeted drug delivery by ADCs. With an MTD of more than 30 mg/kg and an effective dose of 1 mg/kg, cAC10-vcMMAE exhibits a therapeutic window in SCID mice of at least 30. Although the selectivity and stability of cAC10-vcMMAE shown in vitro and in the therapeutic window demonstrated in rodent models suggest that ADC is effective, future toxicology studies in nonhuman primates are clearly needed. Because cAC10-vcMMAE binds to CD30 of human and nonhuman primates, but not mouse CD30 (data not shown), it will be critical to evaluate the toxicity of cAC10-vcMMAE in nonhuman primates. The outcome of such studies may be more predictive of the tolerability and untoward toxicities in humans. Taken together, these data suggest that cAC10-vcMMAE is a highly potent and selective agent against CD30+ malignancies and that it may have significant clinical benefit for treating CD30+ neoplasias.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 8, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0039.

The authors are employed by Seattle Genetics, whose potential product was studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Nick-Vincent Maloney for assistance in sample analysis by mass spectrometry.