Abstract

The chemokines CXCL9, 10, and 11 exert their action via CXC chemokine receptor-3 (CXCR3), a receptor highly expressed on activated T cells. These interferon γ (IFNγ)–induced chemokines are thought to be crucial in directing activated T cells to sites of inflammation. As such, they play an important role in several chronic inflammatory diseases including ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, artherosclerosis, and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions of the skin. In this study, we first demonstrate that in COS-7 cells heterologously expressing CXCR3, CXCL11 is a potent activator of the pertussis toxin (PTX)–sensitive p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Akt/phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) pathways. Next, we show that these signal transduction pathways are also operative and PTX sensitive in primary human T cells expressing CXCR3. Importantly, abrogation of these signaling cascades by specific inhibitors did not block the migration of T cells toward CXCR3 ligands, suggesting that MAPK and Akt activation is not crucial for CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis of T cells. Finally, we demonstrate that CXCR3-targeting chemokines control T-cell migration via PTX-sensitive, phospholipase C pathways and phosphatidylinositol kinases other than class I PI3Kγ.

Introduction

Chemokines are a group of small, secreted and heparin-binding proteins that are not only active as chemotactic factors but also as end-point effectors of immune protective functions. These proteins are classified into Cys-Xaa-Cys (CXC), Cys-Cys (CC), Cys (C), and Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Xaa-Cys (CX3C) chemokines based on the position of characteristic structure determining cysteine residues within their N-terminal part.1-4 They are produced locally in the tissues and exert their action on leukocytes by binding to specific G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) embedded within the membrane of their respective target cells. Typically, the binding of a chemokine to its cognate GPCR triggers the activation of multiple signal transduction pathways, including a transient intracellular rise in Ca2+.5 To date, about 50 different chemokines and at least 18 different receptors have been identified.4

For several chemokines it has been shown that receptor binding also activates the p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (extracellular signal–regulated kinase) pathway in multiple cell types.6-11 Blockade of MAPK activation inhibited eotaxin-induced eosinophil rolling in vivo and chemotaxis in vitro10 as well as CXCL12-mediated chemotaxis of CD4+ T cells12 pointing toward a crucial role of MAPK activation in leukocyte migration.

The chemokines CXCL9, 10, and 11 (formerly known as Mig, IP-10, and IP-9/I-TAC, respectively) exert their action via CXC chemokine receptor-3 (CXCR3), a receptor highly expressed on activated T cells.13,14 These interferon γ (IFN-γ)–induced chemokines are thought to be crucial in directing activated T cells to sites of inflammation where they play an important role in Th1-mediated immune responses. Expression of the CXCR3-targeting chemokines have been demonstrated in several chronic inflammatory diseases including ulcerative colitis,15 multiple sclerosis,16,17 hepatitis C–infected liver,18 artherosclerosis,19 delayed-type hypersensitivity skin reactions, and chronic skin inflammations.20,21 However, to date little is known about the intracellular events following agonist binding to CXCR3, except for Ca2+ mobilization, in T cells.14,22-24

In this study we have delineated several signaling pathways of CXCR3 ligands, in particular of CXCL11, which appears to be the most potent agonist in all assays used. We show that CXCR3 ligands are able to activate the p44/p42 MAPK and Akt/PI-3 kinase signaling cascades in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells and primary human T cells. Chemotaxis of T cells, however, is not mediated by these kinases but controlled via Gi- and phospholipase C–dependent pathways and phosphatidylinositol kinases other than class I PI3Kγ.

Materials and methods

Materials

Cell culture media and supplements were obtained from GIBCO BRL (Carlsbad, CA). CXCL10 (IP-10) was obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and CXCL11 (IP-9/I-TAC) was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase) inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) and Promega (Leiden, The Netherlands), respectively. The phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122, its inactive analog U73343, phosphatidylinositol kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002, and pertussis toxin were obtained from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie B.V., Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). The hCXCR3 in pcDNA III was a gift from Dr B. Moser (Theodor-Kocher Institute, University of Bern, Switzerland).14

Cell culture and transfection

COS-7 cells were grown at 5% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Transfection of COS-7 cells was performed with diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)–dextran. The total amount of DNA in transfected cells was kept constant by addition of the empty vector. Transfected cells were maintained in serum-free medium. Isolations, activation, and culturing of human T lymphocytes were performed as described previously.22

Chemotaxis assays

The assay for chemotaxis was performed in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) carrying Transwell permeable supports with a 5-μm polycarbonate membrane. Cultured T cells were washed once and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 containing 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Medium alone or supplemented with chemokine was placed in the lower compartment, and cells were loaded onto the inserts at 0.5 × 106/100 μL for each individual assay. Chambers were incubated for 120 minutes in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 37°C. After the incubation period, numbers of T cells migrating to the lower chamber were counted under a microscope using a hemocytometer (VWR International, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Viability was checked with trypan blue exclusion. All conditions were tested at least in triplicate; statistic evaluation was performed using the Student t test.

Cell stimulation

If not stated otherwise, interleukin 2 (IL-2)–expanded activated T cells were serum starved overnight in medium supplemented with 400 U/mL IL-2 and 0.2% BSA. The cells were washed twice and resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 20 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4 (2 × 107 cells/mL). Aliquots of 2 × 106 cells for immunoblotting were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C and then stimulated with the appropriate agonist at indicated time intervals. Incubations were terminated by centrifugation and pelleted cells were lysed as described under Western blot analysis. COS-7 cells were serum starved and stimulated as indicated in the figures.

Western blot analysis

Transiently transfected COS-7 cells (48 h after transfection) and IL-2–expanded activated T cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 2 μg/mL of aprotinin and leupeptin), sonicated, separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Antibodies recognizing p44/p42 MAPK, Akt, phospho-Akt (S473) (New England Biolabs) were used in combination with a goat antirabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Biorad, Hercules, CA). The antibody recognizing phospho-p44/p42 MAPK (T202/Y204) (New England Biolabs) was used in combination with a goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Biorad). Protein bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and directly quantified using an Image station (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA).

Actin polymerization assay

Cells were washed 3 times in RPMI 1640 and resuspended in assay medium (RPMI 1640 with 0.1% BSA [BSA, fraction V; Sigma]) in a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Prior to the experiment, the cells and chemokine were kept at room temperature for 10 minutes. The chemokine was subsequently added to the cell suspension (10 nM). At indicated time points, 100 μL of cell suspension was transferred to 100 μL of fixation solution (4% paraformaldehyde [PFA]). Cells were incubated in the fixation solution for at least 15 minutes. Thereafter, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 100 μL of permeabilization reagent (0.1% Triton-X 100). After 10 minutes of incubation in this solution, cells were washed, blocked with 1% BSA (5 minutes), washed, and incubated with 0.5 μM rhodaminephalloidin (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) to visualize the F-actin. After 30 minutes, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.25% BSA. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (FACScan; BD Biosciences, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands).

Results

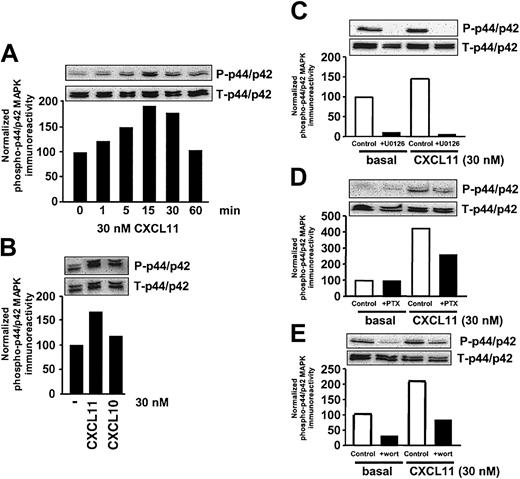

CXCR3 agonists induce activation of p44/p42 MAPK in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells

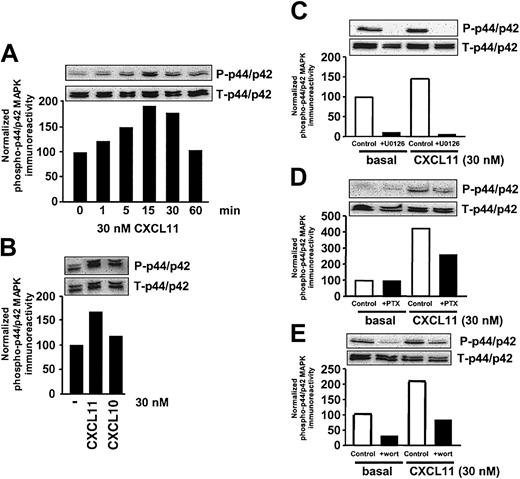

We first examined the relative potencies of CXCR3 agonists CXCL11 and CXCL10 to activate the p44/p42 MAPK–signaling pathway. To this end, the human CXCR3 receptor was transiently expressed into COS-7 cells. Exposure of CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells to 30 nM CXCL11 for different periods of time resulted in a time-dependent increase in endogenous MAPK activity as detected by an increase in phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK, measured using an antibody recognizing the phosphorylated form of p44/p42 MAPK (Figure 1A). A maximal transient increase in phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK was observed after 15 minutes' exposure of cells to CXCL11 at a concentration of 30 nM (Figure 1A). The other well-known CXCR3 agonist CXCL10 (IP-10) also induced an increase in phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK, albeit to a lesser extent (Figure 1B).

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of p44/p42 MAPK in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells transiently transfected with CXCR3 (2.0 μg plasmid/106 cells) were stimulated for different periods of time with 30 nM CXCL11. Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-p44/p42 (P-p44/p42) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total MAPK (T-p44/p42) expression on stripped blots. (B) CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were incubated with CXCL10 and 11 (30 nM) for 15 minutes before lysis of the cells. (C-E) Involvement of Raf-MEK–(C), Gi- (D), and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced (15 minutes, 30 nM) p44/p42 MAPK phosphorylation. CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of U0126 (10 μM, 30 minutes; C), PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D), or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of p44/p42 MAPK in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells transiently transfected with CXCR3 (2.0 μg plasmid/106 cells) were stimulated for different periods of time with 30 nM CXCL11. Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-p44/p42 (P-p44/p42) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total MAPK (T-p44/p42) expression on stripped blots. (B) CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were incubated with CXCL10 and 11 (30 nM) for 15 minutes before lysis of the cells. (C-E) Involvement of Raf-MEK–(C), Gi- (D), and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced (15 minutes, 30 nM) p44/p42 MAPK phosphorylation. CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of U0126 (10 μM, 30 minutes; C), PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D), or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

As expected, incubation of cells expressing CXCR3 with the specific MEK inhibitors U0126 (10 μM) or PD98059 (10 μM, data not shown) led to a complete abolishment of basal and CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK, confirming the involvement of the Raf-MEK pathway (Figure 1C). CXCR3 belongs to the class of Gi-coupled receptors that are known to activate p44/p42 MAPK in COS-7 cells25,26 through the release of Gβγ subunits leading to activation of PI3K and Ras.27 In order to examine the involvement of the Gi-signaling pathway in CXCR3-mediated signaling to p44/p42 MAPK, cells were treated with pertussis toxin (PTX, 100 ng/mL) for 48 hours. Pretreatment of cells with PTX resulted in a partial reduction of CXCR3-induced increase in MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 1D). Involvement of PI3K was examined by pretreatment of cells for 30 minutes with wortmannin (100 nM). Pretreatment of cells with wortmannin led to a complete inhibition of basal and CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of MAPK (Figure 1E).

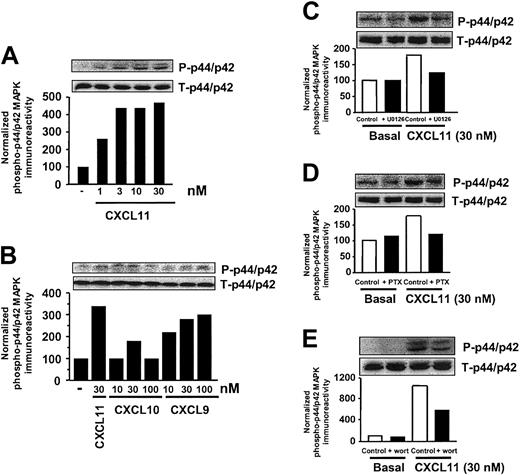

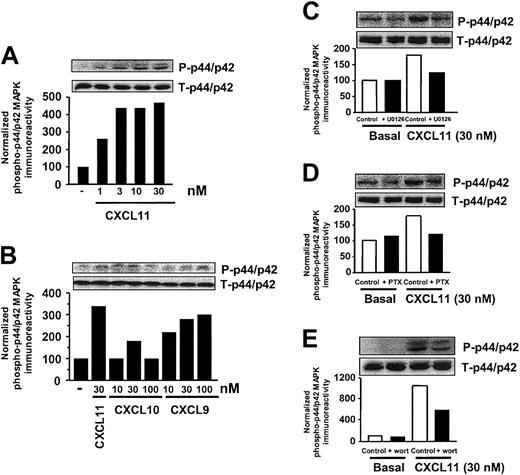

CXCR3 agonists induce activation of p44/p42 MAPK in T lymphocytes

As previously shown, T lymphocytes treated for 10 days with IL-2 express CXCR3.14,22 In IL-2–expanded, activated T cells, CXCL11 induced a time- (data not shown) and concentration-dependent increase in phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK (Figure 2A). A maximal increase in phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK, ranging from a 2- to 5-fold increase, was observed after 5 to 15 minutes' stimulation of cells with CXCL11, varying with the T-cell donor. Analogous to the observations made in CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells, the activation of p44/p42 MAPK by CXCL11 appeared to be transient, since no increase in phosphorylation of MAPK was detected after 60 minutes' exposure of cells to CXCL11 (data not shown). A maximal effect by CXCL11 was reached at a concentration of 3 nM (Figure 2A), whereas CXCL9 and in particular CXCL10 were less potent in phosphorylating p44/p42 MAPK (Figure 2B).

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of p44/p42 MAPK in T lymphocytes. (A-B) Activated IL-2–expanded blood T cells were incubated for 15 minutes with various concentrations of CXCL11 (A), CXCL10 (B), or CXCL9 (B) before lysis of the cells. Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-p44/p42 (P-p44/p42) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total MAPK (T-p44/p42) expression on stripped blots. (C-E) Involvement of Raf-MEK–(C), Gi- (D), and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced p44/p42 MAPK phosphorylation. T cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of U0126 (10 μM, 30 minutes; C), PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D), or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E), and exposed to CXCL11 (15 minutes, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of p44/p42 MAPK in T lymphocytes. (A-B) Activated IL-2–expanded blood T cells were incubated for 15 minutes with various concentrations of CXCL11 (A), CXCL10 (B), or CXCL9 (B) before lysis of the cells. Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-p44/p42 (P-p44/p42) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total MAPK (T-p44/p42) expression on stripped blots. (C-E) Involvement of Raf-MEK–(C), Gi- (D), and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced p44/p42 MAPK phosphorylation. T cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of U0126 (10 μM, 30 minutes; C), PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D), or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E), and exposed to CXCL11 (15 minutes, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

In activated T cells, CXCR3-mediated activation of p44/p42 MAPK appeared to be mediated by the Raf-MEK pathway, as the MEK inhibitor (U0126) completely inhibited the CXCL11-induced increase in MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 2C). The CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK in T cells appeared to be Gi and partially PI3K mediated, as preincubation of cells with PTX (48 h, 100 ng/mL; Figure 2D) resulted in a complete inhibition, whereas preincubation of cells with wortmannin (30 minutes, 100 nM; Figure 2E) led to a partial attenuation, of the CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK.

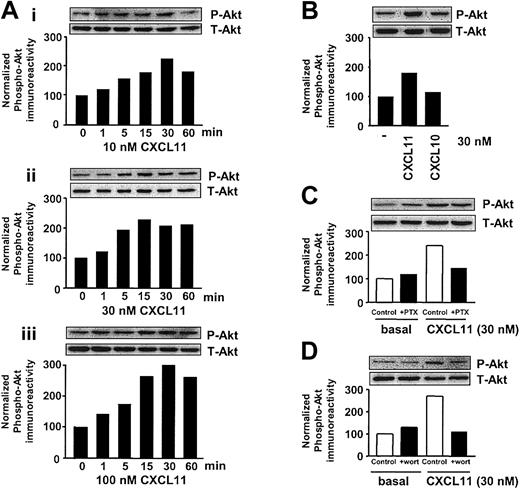

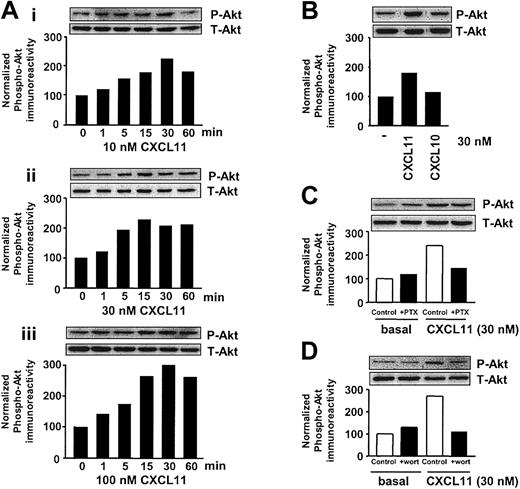

CXCR3 agonists phosphorylate Akt in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells

The serine/threonine kinase Akt is known to be critical for cell survival, proliferation, and gene expression.28 In addition, Akt has been shown to be implicated in cell migration.29-31 Exposure of CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells to CXCL11 resulted in a marked and sustained increase in phosphorylation of endogenous Akt in COS-7 cells, as evidenced by immunoblotting with a phosphospecific antibody (Figure 3A). CXCL11 induced a time- and concentration-dependent phosphorylation of Akt, reaching a maximal effect with 10 nM after 15 to 30 minutes' exposure (Figure 3A). CXCL11 induced a marked increase in phosphorylation of Akt at 30 nM, while at this concentration CXCL10 induced only a marginal increase in phosphorylation of Akt.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of Akt in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells transiently transfected with CXCR3 (2.0 μg plasmid/106 cells) were stimulated for different periods of time with 10 (Ai), 30 (Aii), and 100 (Aiii) nM CXCL11, and phosphorylation of Akt was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-Akt (P-Akt) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total Akt (T-Akt) expression on stripped blots. (B) CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were incubated with 30 nM CXCL11 or CXCL10 for 15 minutes before lysing the cells. (C-D) Involvement of Gi- (C) and PI3K–signaling pathway (D) in CXCL11-induced Akt phosphorylation. CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; C) or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; D) and exposed to CXCL11 (15 minutes, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of Akt in CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells transiently transfected with CXCR3 (2.0 μg plasmid/106 cells) were stimulated for different periods of time with 10 (Ai), 30 (Aii), and 100 (Aiii) nM CXCL11, and phosphorylation of Akt was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-Akt (P-Akt) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total Akt (T-Akt) expression on stripped blots. (B) CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were incubated with 30 nM CXCL11 or CXCL10 for 15 minutes before lysing the cells. (C-D) Involvement of Gi- (C) and PI3K–signaling pathway (D) in CXCL11-induced Akt phosphorylation. CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; C) or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; D) and exposed to CXCL11 (15 minutes, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

Involvement of Gi-signaling pathways in the CXCR3-induced signaling to Akt was determined by treatment with PTX. As can be seen in Figure 3C, PTX treatment resulted in a marked inhibition of CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of Akt. To study the role of PI3K (a known key player in the activation of Akt32 ), CXCR3-expressing cells were treated with PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (30 minutes, 100 nM). As expected, inhibition of PI3K resulted in a total abolishment of CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 3D).

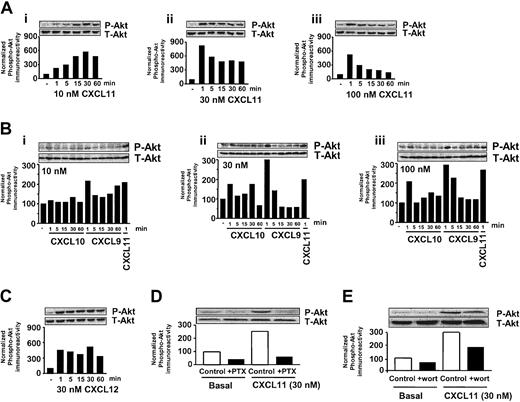

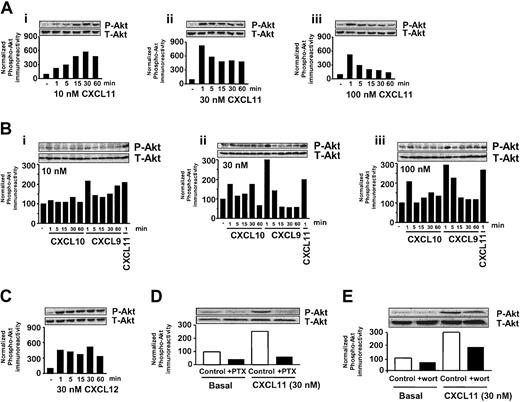

CXCR3 agonists phosphorylate Akt in T lymphocytes

Also in activated T cells, CXCL11 generated a time- and concentration-dependent increase in phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 4Ai-iii). At low concentrations of CXCL11 (10 nM), a maximal increase in phosphorylation of Akt was detected after 30 minutes' incubation. Remarkably, at higher concentrations of CXCL11 (30 and 100 nM) a marked increase in Akt phosphorylation was already observed after 1-minute exposure of cells. Akt phosphorylation levels remained at an elevated level for at least 60 minutes when cells were exposed to 30 nM, while at higher concentrations of CXCL11 (100 nM) a gradual decrease to basal levels was observed. Again, the ability of CXCL10 to induce an elevation of Akt phosphorylation was less pronounced compared with CXCL11 at the different concentrations (Figure 4Bi-iii). CXCL9 appeared to exert a similar increase of Akt phosphorylation compared with CXCL11 after 1 minute of exposure (Figure 4Bi-iii). However, CXCL9 was not able to induce a sustained elevated level of Akt phosphorylation.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of Akt in T lymphocytes. (A-C) T cells were stimulated for different periods of time with 10, 30, and 100 nM CXCL11 (Ai-iii), CXCL10 (Bi-iii), CXCL9 (Bi-iii), or CXCL12 (C), and phosphorylation of Akt was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-Akt (P-Akt) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total Akt (T-Akt) expression on stripped blots. (D-E) Involvement of Gi- (D) and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced Akt phosphorylation. T cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D) or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E) and exposed to CXCL11 (1 minute, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

CXCR3 agonists stimulate activation of Akt in T lymphocytes. (A-C) T cells were stimulated for different periods of time with 10, 30, and 100 nM CXCL11 (Ai-iii), CXCL10 (Bi-iii), CXCL9 (Bi-iii), or CXCL12 (C), and phosphorylation of Akt was determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti–phosho-Akt (P-Akt) antibodies. Phosphorylation was quantified by chemiluminescence and corrected for total Akt (T-Akt) expression on stripped blots. (D-E) Involvement of Gi- (D) and PI3K–signaling pathway (E) in CXCL11-induced Akt phosphorylation. T cells were grown in serum-free medium in the presence of PTX (100 ng/mL, 48 h; D) or wortmannin (wort) (100 nM, 30 minutes; E) and exposed to CXCL11 (1 minute, 30 nM) before lysis and Western blot analysis. A representative experiment of at least 2 independent experiments is shown.

As a control, activated T cells were also exposed to CXCL12 (SDF-1 [stromal cell–derived factor 1]), which binds to its cognate receptor CXCR4 on these cells. As previously shown by Tilton et al,11 CXCL12 (SDF-1) induced a sustained increase in activation of Akt (Figure 4C). CXCL11-mediated phosphorylation of Akt appeared to be GI dependent as treatment of cells with PTX abrogated the CXCL11-induced increase in phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 4D). In addition, PI3K appeared to be involved as preincubation of cells with wortmannin markedly attenuated the CXCL11-induced phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 4E).

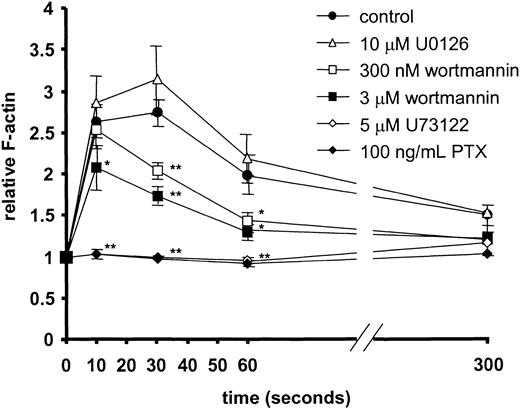

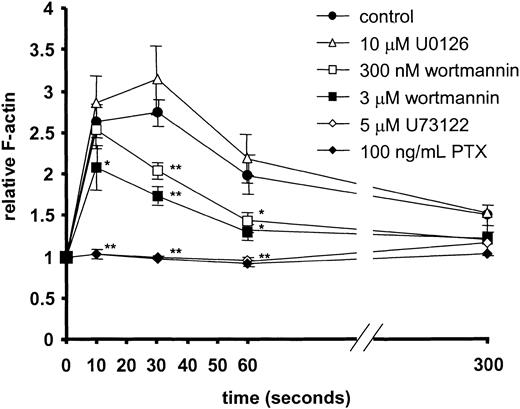

CXCR3-mediated actin polymerization and chemotaxis of T lymphocytes

Finally, the role of MEK-1, PI3K/PI4K, phospholipase C, and Gi protein was determined in CXCR3-induced actin polymerization and CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis of T cells. Addition of CXCL11 to CXCR3-expressing primary T cells induced a rapid and marked onset of F-actin polymerization (Figure 5). CXCL11-stimulated actin polymerization was not inhibited by pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Figure 5). Moderate inhibition of CXCL11-mediated actin polymerization was found after 30 seconds when cells were pretreated with 300 nM wortmannin or earlier (10 seconds) when pretreated with higher concentrations of wortmannin (3 μM). Complete inhibition, however, was achieved after pretreatment with pertussis toxin and the PLC inhibitor U73122 (5 μM). The inactive analog of U73122, U73343, had no effect (not shown).

CXCL11-induced F-actin formation in primary human T cells and the effect of inhibitors. At 10, 30, 60, and 300 seconds after 10 nM CXCL11 stimulation, the levels of F-actin were determined by FACS analysis. Significantly lower F-actin levels were found after pretreatment with PTX, U73122, and high concentrations of wortmannin. No effects were observed with the MEK inhibitor U0126 and the inactive analog of U73122 (U73433; data not shown). Data shown are the average of independent experiments with T cells from 7 different donors. Error bars represent SEM. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from CXCL11-induced actin polymerization without inhibitor (Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .005).

CXCL11-induced F-actin formation in primary human T cells and the effect of inhibitors. At 10, 30, 60, and 300 seconds after 10 nM CXCL11 stimulation, the levels of F-actin were determined by FACS analysis. Significantly lower F-actin levels were found after pretreatment with PTX, U73122, and high concentrations of wortmannin. No effects were observed with the MEK inhibitor U0126 and the inactive analog of U73122 (U73433; data not shown). Data shown are the average of independent experiments with T cells from 7 different donors. Error bars represent SEM. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from CXCL11-induced actin polymerization without inhibitor (Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .005).

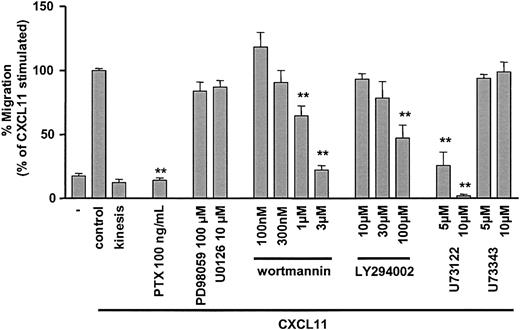

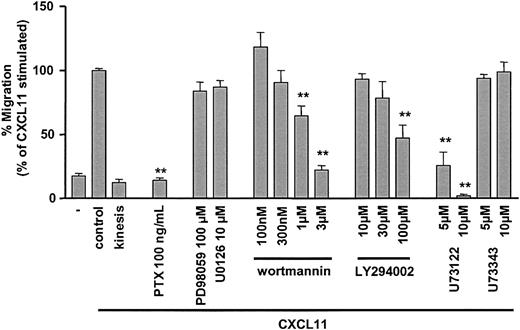

The role of MEK-1 and p44/p42 MAPK in CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration was studied using the MEK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 (Figure 6). Neither PD98059 nor U0126 caused inhibition of CXCL11-induced chemotaxis. Low concentrations of wortmannin, selective for class I PI3K inhibition, did not block CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration (Figure 6). However, at high concentrations of wortmannin (≥ 1 μM) significant inhibition of CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration was observed. Similar results were obtained with the structurally distinct PI3/PI4K inhibitor LY294002. At concentrations selective for class I PI3K inhibition no effects were detected, while increased concentrations induced partial inhibition of CXCL11-induced T-cell migration. Finally, CXCL11-induced migration was completely blocked by pertussis toxin pretreatment and the selective inhibitor of phospholipase C (U73122), while the inactive analog of U73122 (U73343) had no effect (Figure 6). This confirmed the crucial role of Gi proteins and PLC in CXCR3-mediated migration of human primary T cells. None of the inhibitors except for the specific PLC inhibitor U73122 affected chemokinesis (data not shown).

CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis of activated, primary human T lymphocytes and the effect of inhibitors. The chemotactic activity of activated IL-2–expanded, blood-derived human T cells toward 30 nM CXCL11 was determined by the Transwell migration system. Migration is reduced by pretreatment with PTX, the PLC inhibitor U73122, and high concentrations of the kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002. No significant effects on chemotactic activity were found with the inactive analog of U73122 (U73433) and the MEK inhibitors U0126 and PD98059. Data shown are the average of experiments with T cells from at least 5 different donors, except for the different LY294002 concentrations (n = 4). Chemotaxis is expressed as percentage of cells migrating in comparison to 30 nM CXCL11 (set at 100% for each individual donor). Error bars represent SEM. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from CXCL11-induced chemotaxis without inhibitor (Student t test; **P < .001).

CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis of activated, primary human T lymphocytes and the effect of inhibitors. The chemotactic activity of activated IL-2–expanded, blood-derived human T cells toward 30 nM CXCL11 was determined by the Transwell migration system. Migration is reduced by pretreatment with PTX, the PLC inhibitor U73122, and high concentrations of the kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002. No significant effects on chemotactic activity were found with the inactive analog of U73122 (U73433) and the MEK inhibitors U0126 and PD98059. Data shown are the average of experiments with T cells from at least 5 different donors, except for the different LY294002 concentrations (n = 4). Chemotaxis is expressed as percentage of cells migrating in comparison to 30 nM CXCL11 (set at 100% for each individual donor). Error bars represent SEM. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from CXCL11-induced chemotaxis without inhibitor (Student t test; **P < .001).

Discussion

T-cell migration into sites of inflammation is a complex process in which several cell surface molecules (eg, adhesion molecules, integrins, and their ligands), act together. Soluble mediators, mainly chemokines, are central in both activating and directing T-cell subsets to target tissues. However, the signaling pathways involved in the regulation of these processes are still poorly defined. CXCR3 is predominantly expressed on activated T cells and activation by CXCL9, 10, and 11 leads to Ca2+ mobilization14,22-24 and chemotaxis in T cells.22 Recently, CXCL9 was shown to stimulate also the p44/p42 MAPK pathway in melanoma cells33 and both CXCL9 and 10 were reported to activate the Ras/ERK (extracellular signal–regulated kinase), Src, and the PI3K/Akt pathways34 in tissue-specific pericytes. However, CXCR3-signaling events in T cells as well as the relative effects of CXCL9, 10, and 11 on activation of the p44/p42 MAPK- and Akt-signaling pathways on cells heterologously expressing CXCR3 are thus far unknown.

CXCR3 induces activation of the p44/p42 MAPK and Akt/PI3K pathways in T cells

In CXCR3-transfected COS-7 cells and in activated primary human T cells, CXCL 11, 10, and 9 induce activation of the p44/p42 MAPK- as well as the Akt-signaling pathways. However, considerable differences exist between these CXCR3-activating chemokines, with CXCL11 being a more potent ligand than CXCL9 and CXCL10. The potencies of CXCL9 and in particular CXCL10 to phosphorylate p44/p42 MAPK and Akt are lower than that observed for CXCL11 at different time points. These observations are in agreement with the reduced affinities reported for CXCL9 and 10 compared with 11 for CXCR3, with CXCL11 being unique as it interacts with 2 receptor states of CXCR3.35 In both model systems, CXCR3 agonists activate p44/p42 MAPK and Akt in a Gi- and PI3K–sensitive manner. It should be noted that the efficacy of chemokines is subject to T-cell donor variability, while their rank order of potency remains the same. As signaling induced by the different chemokines in CXCR3-expressing COS-7 is similar to that in activated T cells, CXCR3-expressing COS-7 cells may function as a useful alternative model system.

CXCR3 induces sustained activation of Akt in T cells

Interestingly, CXCR3 activation by CXCL11 leads to sustained phosphorylation of Akt in T cells that is similar to that previously observed for CXCL12 (SDF-1) and CXCR4 but distinct from other chemokine receptors. In the case of CXCR4, persistent activation of Akt by CXCL12 was explained by the fact that CXCL12 and CXCR4 are involved in homeostasis rather than inflammation; sustained activation could protect CXCR4+ cells from undergoing apoptosis, a process that is critical for the activation of T cells.11 Our data not only reveal that persistent activation of the Aktsignaling pathway is not an exclusive property of the CXCL12/CXCR4-signaling pathway but also demonstrate that sustained activation strongly depends on the concentration of the chemokine present in the environment of the receptor. At low concentrations of CXCL11, activation of Akt is sustained, whereas at higher concentrations CXCL11-mediated activation of Akt is transient. Loss of Akt activation might in turn be the signal for chemokine-induced apoptosis as recently demonstrated for CXCL12 and CD4+ T cells.12 In a physiologic context (eg, inflammation) such processes might not only regulate and guide the migration of CXCR3-bearing T cells but also be the trigger for T-cell apoptosis in case of local high expression of CXCL11. Disturbance of such a balance might contribute to the presence of high numbers of CXCR3+ T cells in certain inflammatory diseases (eg, chronic skin inflammations).21

CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration is not dependent on the PI3K /Akt or the p44/p42 MAPK pathway

Both the PI3K/Akt and the p44/p42 MAPK pathways have been reported to be involved in chemokine-induced migration of various cell types.10,12-14 Additional evidence for PI3K-γ as an important intermediary signal for chemotaxis came from genetic studies using PI3Kγ knock-out mice.36-38 In our study, the potent inhibitors of MEK1/2 (PD98 059 and U0126) were unable to block CXCR3-mediated transmigration of T cells and CXCR3-induced actin polymerization. The inhibitors of PI3K showed a moderate attenuation of CXCR3-mediated transmigration of T cells and actin polymerization at relatively high concentrations. Both MEK1/2 and PI3K inhibitors were active in blocking the CXCL11-mediated phosphorylation of MAPK-p44/p42 and Akt at low concentrations.

Although wortmannin and LY294002 have been used extensively to study the physiologic role of (class I) PI3Ks in various cellular responses (including chemotaxis), contradictory results have been obtained. For example, treatment with these PI3K inhibitors inhibited chemotaxis in some studies6,7 but not in others.39,40 These studies should be interpreted with caution, as it was shown that at higher concentrations (above 100 nM wortmannin or 10 μM LY294002) these compounds inhibit other signaling enzymes, including class II PI3K and PtdIns 4-kinases (PI4Ks).41 As in our transmigration and actin polymerization assays only a moderate inhibition of T-cell migration and actin polymerization is obtained with relative low (PI3K specific) concentrations, we conclude that it is more likely that class II PI3K, PI4K, or related enzymes other than PI3Kγ are involved in CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration. To date, limited information is available on the role of PI4K in cell migration. However, in neutrophils, a close association of PI4K, α3β1 integrin, and transmembrane-4 superfamily (TM4SF) protein (CD151) was demonstrated.42 From this observation, a functionally important role of this complex (including PI4K) in cell migration was suggested.

Our data on the possible involvement of class II PI3K or PI4K are in contrast with the general concept that chemotaxis is regulated via PI3Kγ.43-45 This apparent discrepancy might result (aside from the fact that PI3K inhibitors at high concentrations also inhibited class II PI3K and PI4K41 ), also from the conception that signals involved in the regulation of cell migration act in a species-, cell-, and chemokine/chemokine receptor–dependent fashion (like the different roles of p44/p42 MAPK). The most convincing data pointing toward a crucial role for PI3Kγ in chemotaxis used PI3Kγ knock-out mice and tested CCR5/CXCR4/CXCR2-mediated migration of neutrophils/macrophages.36-38 At this point one cannot exclude that CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis of human T cells is coordinated and regulated in a different way involving class II PI3K or PI4K rather than PI3Kγ.

An important role for MAPK in leukocyte migration came from studies in which blockade of MAPK activation by the MAPK kinase inhibitors led to a decrease in eotaxin-induced eosinophil chemotaxis in vitro as well as inhibition of actin polymerization.10 Similar observations were made for CXCL12-induced migration of CD4+ T cells.12 These pathways are clearly not employed in case of CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration. Two structurally different MAPK inhibitors (PD98059 and U0126) were not able to inhibit CXCR3-induced actin polymerization assays or CXCR3-mediated in vitro transmigration while fully inhibiting phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK. At this point a role for MAPK in the overall process of transendothelial T-cell migration cannot be excluded. Recently, it was shown for eosinophils that under flow conditions CCR3-mediated MAPK signals cause these cells to rapidly decrease their vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)–mediated adherence while enhancing their intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) binding.46 In analogy, recruitment of T cells into sites of inflammations might require CXCR3-mediated MAPK activation for proper adherence during transendothelial migration. In addition, CXCR3 activation of MAPK pathways might be of importance for T-cell function and development. As it was shown that MAPK signaling is involved in T-cell proliferation,47 the observed CXCL11-induced p44/p42 MAPK activation might induce long-term effects on T cells.

CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration is dependent on Gαi, PLC, and PI-kinase signaling

The crucial role of G proteins in chemotaxis of lymphocytes is well known. It is commonly accepted that all chemokine receptors couple to Gi, although some chemokine receptors can also couple to Gαq, Gα11, Gα14, and Gα16 proteins.48-50 As pretreatment of T cells with pertussis toxin completely blocks CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis, it can be concluded that CXCR3 is primarily coupled to Gαi. The preference of CXCR3 coupling to Gαi over Gα16 was also demonstrated in a CHO cell line overexpressing human Gα16.22 PTX treatment of these cells completely abrogates CXCL11-induced Ca2+ signaling, demonstrating that CXCR3 couples to endogenously Gαi and not to Gα16.

The presence of the PLC-signaling pathways in T cells and the ability of chemokines to activate this system were previously demonstrated for CXCL8/CXCR2.51 Moreover, PLCβ activation of heterologously expressed chemokine receptors was shown for CCR1 and 2.49 The major role of PLC as determinant of chemokinemediated chemotaxis of T cells (as described in this manuscript), however, is hitherto not recognized. Strikingly, the PLC pathway was thus far considered to play a role in down-modulation of chemotaxis38 rather than being crucial for T-cell chemotaxis. The fact that the specific inhibitor of PLC attenuated chemokinesis further stresses its pivotal role in T-cell motility. It remains to be determined which downstream signaling moieties of PLC are responsible for the control of the chemotactic process. Calmodulin kinase, myosin light-chain kinase, rho kinase, or other small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) are potential candidates, which are currently under investigation.

In summary, our experiments indicate that both PI3Kγ (resulting in Akt phosphorylation) and MEK1/2 (resulting in p44/p42 MAPK phosphorylation) are functionally active in translating CXCR3-triggered signals in human T lymphocytes. However, these signals are not directly involved in CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration, which is primarily regulated in a manner dependent on Gi, PLC, and phosphatidylinositol kinases other than class I PI3Kγ.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 15, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3945.

Supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (RUL 2000-2168; C.P.T.); M.J.S. is supported by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.