Abstract

Aneuploid is ubiquitous in multiple myeloma (MM), and 4 cytogenetic subcategories are recognized: hypodiploid (associated with a shorter survival), pseudodiploid, hyperdiploid, and near-tetraploid MM. The hypodiploid, pseudodiploid, and near-tetraploid karyotypes can be referred to as the nonhyperdiploid MM. Immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) translocations are seen in 60% of patients. We studied the relation between aneuploidy and IgH translocations in MM. Eighty patients with MM and abnormal metaphases were studied by means of interphase fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect IgH translocations. We also studied a second cohort of 199 patients (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG]) for IgH translocations, chromosome 13 monosomy/deletions (Δ13), and ploidy by DNA content. Mayo Clinic patients with abnormal karyotypes and FISH-detected IgH translocation were more likely to be nonhyperdiploid (89% versus 39%, P < .0001). Remarkably, 88% of tested patients with hypodiploidy (16 of 18) and 90% of tested patients with tetraploidy (9 of 10) had an IgH translocation. ECOG patients with IgH translocations were more likely to have nonhyperdiploid MM by DNA content (68% versus 21%, P < .001). This association was seen predominantly in patients with recurrent chromosome partners to the IgH translocation (11q13, 4p16, and 16q23). The classification of MM into hyperdiploidy and nonhyperdiploidy is dictated largely by the recurrent (primary) IgH translocations in the latter. (Blood. 2003;102:2562-2567)

Introduction

The study of chromosome abnormalities in multiple myeloma (MM) has been fraught with difficulties in elucidating an underlying order within the perceived cytogenetic chaos.1,2 Abnormal metaphases are observed in only one third of patients. This problem has prevented an accurate description of the genetic nature of MM.2 While aneuploidy is common in MM, several cytogenetic subgroups can be identified on the basis of the type of numerical chromosomal abnormalities.3,4 Work done by our group and others has shown that these same subgroups are discernible by DNA content analysis (DNA flow cytometry) and by chromosome complement (karyotype analysis).5-7 Four subcategories are readily identified: hypodiploid MM, pseudodiploid MM, hyperdiploid MM, and the near-tetraploid MM (also call hypotetraploid MM).7

Patients with either hypodiploid or pseudodiploid MM are characterized by various structural chromosomal abnormalities and monosomies. Patients with hyperdiploid MM have recurrent trisomies, particularly of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, 11, 15, 17, and 19. Near-tetraploid karyotypes are usually identical duplicates of diploid or pseudodiploid karyotypes, as coexisting 2N metaphases are usually seen with the 4N component.6,7 Because of the cytogenetic similarities between the near-tetraploid MM karyotypes and the hypodiploid and pseudodiploid MM, we and others have proposed 2 major aneuploidy groups: hyperdiploid MM (48 to 74 chromosomes) and nonhyperdiploid MM (fewer than 48 or more than 74 chromosomes).6,7

The ploidy subcategories are associated with distinct clinical presentation and outcomes. In particular, hypodiploid MM is associated with a shortened survival and lower likelihood of response to therapy.6-10 The prognostic significance of hypodiploid is evident when it is detected by karyotype analysis and DNA index, and is similar to that of chromosome 13 monosomy.6,7,10 In this study, we show that immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) translocations are highly associated with ploidy categories.

Patients and methods

These studies were conducted under institutional review board (IRB) approval and following the Helsinki guidelines for research with human subjects.

Mayo Clinic patients

Samples. In total, 109 patients from the Mayo Clinic were studied. We identified all patients entered into the clinical cytogenetic database at Mayo with a referral diagnosis of MM or other monoclonal gammopathy. Patients with clinical or pathologic (by marrow examination or karyotype) evidence of myelodysplasia or acute leukemia were excluded. To be included in our series, patients were required to have abnormal metaphases, and thus we studied only patients with MM. We initially identified 254 patients, and have previously published the overall description of these database results.7 From these 254 patients, we used samples from a cohort of 109 patients who gave a research bone marrow sample obtained under informed consent; samples were collected at the time of routine clinical procurement (Table 1).

Bone marrow samples and karyotype analysis. The samples for karyotype analysis of Mayo patients were obtained at the time of routine clinical procurement. The karyotypes were obtained with the use of both short-term and long-term cultures and processed by conventional cytogenetic techniques.11 We used the following chromosome count values to define ploidy categories: hypodiploid (up to 44 chromosomes), pseudodiploid (45 to 47 chromosomes), hyperdiploid (48 to 74 chromosomes), and near-tetraploid (75 or more chromosomes).

Stored cells and slides. Research sample cells were enriched for the mononuclear compartment by means of the Ficoll method. Cell cytospin slides were performed at a density of approximately 5 × 105 cells; slides were unfixed and stored at −20°C for future use.

ECOG patient samples

We have studied and previously reported on 351 patients entered into the clinical trial E9486/E9487 for major cytogenetic abnormalities using interphase fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH); these abnormalities are 14q32 translocations (which include 14q32 without an identifiable partner), t(4;14)(p16.3;q32), t(11;14)(q13;q32), and t(14;16)(q32;q23), and Δ13.12-17 Karyotype analysis was not routinely performed on these patients, and metaphases were thus not available for analysis (and are not included in the database). We now report here on 199 patients in whom results were available for all the IgH translocation assays and on Δ13 and ploidy determination by DNA index.

cIg-FISH studies

Interphase FISH was performed by means of standard hybridization conditions as we have previously described.18 Briefly, we performed double-color FISH and simultaneous immunofluorescent detection of the clonotypic plasma cells.

FISH probes

To detect IgH translocations, we used probes that bracket this locus and as we have previously described (VH/CH probes).19-21 These probes are able to detect any IgH translocation via segregation of the signals (“break-apart” strategy). For the patients enrolled in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) study, and reported on here, we also used probes (in addition to VH/CH) to detect any of the following 3 most common IgH translocations by means of a fusion strategy: t(4;14)(p16.3;q32), t(11; 14)(q13;q32), and t(14;16)(q32;q23).13-17

DNA content analysis

The flow cytometry determination of total DNA content was done as previously described on the ECOG patient samples by means of standard staining with propidium iodide.22 This technique is better able to determine hyperdiploidy than hypodiploidy given the close proximity of the tracing for hypodiploid MM DNA peak to the pseudodiploid peak. The following DNA index criteria were used for the determination of ploidy: less than 0.95 hypodiploid, 0.95 to 1.05 pseudodiploid, more than 1.05 hyperdiploid, less than 1.74 hyperdiploid, and more than 1.75 tetraploid.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize and report on the patients in this study. The Fisher exact test was used to test for associations between translocations and ploidy status. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to test if a relationship existed between the presence of IgH translocation and the number of chromosomes in hypodiploid, pseudodiploid, and hyperdiploid patients. Patients were considered as having an IgH translocation if they had a positive VH/CH assay or any 1 of the 3 specific translocations as positive by the fusion strategy.

Results

Mayo Clinic patients (n = 109)

Karyotype analysis and 14q32 translocations. Results of karyotypes and clinical and prognostic effects of translocations observed among these patients have been previously reported.7 We found in our previous study that the t(11;14)(q13;q32) was observed in 29 (11%) of 254 patients. As we and others have previously demonstrated, the most frequent trisomies were those of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 15, 19, and 21.

Correlation between karyotypes and FISH-detected IgH translocations. Eighty patients with karyotype analysis and detectable chromosome abnormalities were also studied for the presence of IgH translocations by interphase FISH (VH/CH). Of these patients, 44 (55%) had evidence of an IgH translocation, and 36 (45%) patients had normal IgH. Patients with IgH translocations were much more likely to be nonhyperdiploid (39 of 44, 89%) than those without an IgH translocation (14/36, 39%) (P < .0001) (Table 2).

Correlation between t(11;14)(q13;q32) and ploidy status. Subsequently, we analyzed the 29 patients with a karyotypically detected t(11;14)(q13;q32) and found the same association (Figure 1). Of 29 patients with t(11;14)(q13;q32), 27 (93%) belonged to the nonhyperdiploid category (Table 2); 24 were hypodiploid/pseudodiploid; and 3 were near-tetraploid with 75, 80, and 83 chromosomes. Only 2 patients had hyperdiploidy: 1 with 49 chromosomes and 1 with 65 chromosomes. Accordingly, when we analyzed all patients (n = 109) according to the presence of any IgH translocation by either method of detection (VH/CH [n = 80] or t(11;14)(q13;q32) by karyotype [n = 29]), patients with nonhyperdiploid MM were significantly more likely to harbor an IgH translocation than patients with hyperdiploid MM (83% versus 24%, P < .0001) (Table 2).

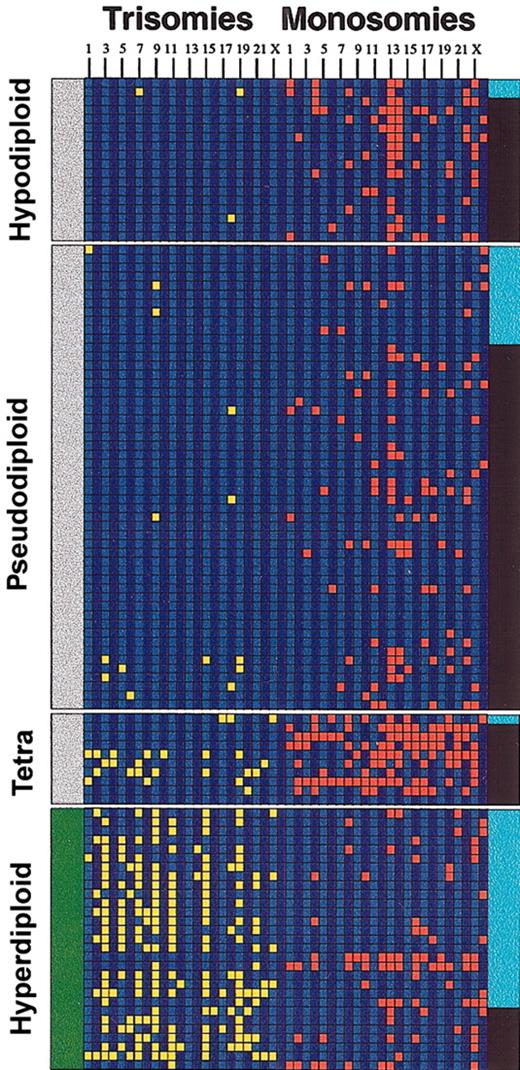

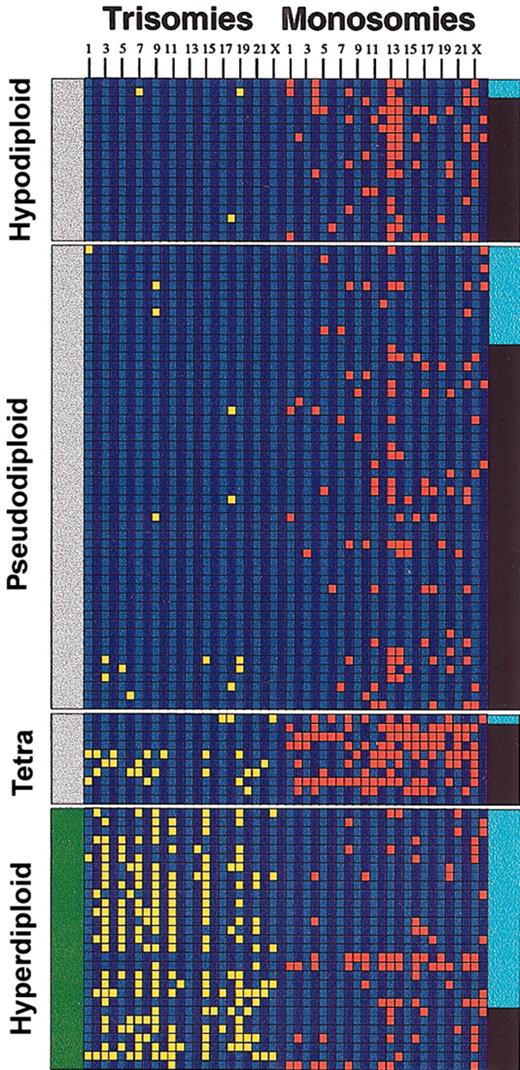

Aneuploidy and IgH translocations. The diagram depicts the relationship between IgH translocations, numerical chromosome abnormalities, and ploidy in the 109 Mayo Clinic patients studied. Each column represents a chromosome trisomy/monosomy as detected by karyotype analysis (chromosomes 1 to 23 and Y from left to right). A trisomy (yellow) is shown if the abnormality was present in the abnormal metaphase irrespective of the number of times present. Likewise, a monosomy (red) is shown if the abnormality was present in the abnormal metaphase irrespective of the number of times present. A black band in the right margin indicates that the patient has an IgH translocation, and a light blue band is indicative of absence of the translocation. The left margin indicates whether the patients belong to the nonhyperdiploid variant MM (gray bar at the left indicates nonhyperdiploid MM) or the hyperdiploid variant MM (green bar at the left indicates hyperdiploid). Note the higher proportion of IgH translocations in the nonhyperdiploid group. Tetra indicates tetraploid.

Aneuploidy and IgH translocations. The diagram depicts the relationship between IgH translocations, numerical chromosome abnormalities, and ploidy in the 109 Mayo Clinic patients studied. Each column represents a chromosome trisomy/monosomy as detected by karyotype analysis (chromosomes 1 to 23 and Y from left to right). A trisomy (yellow) is shown if the abnormality was present in the abnormal metaphase irrespective of the number of times present. Likewise, a monosomy (red) is shown if the abnormality was present in the abnormal metaphase irrespective of the number of times present. A black band in the right margin indicates that the patient has an IgH translocation, and a light blue band is indicative of absence of the translocation. The left margin indicates whether the patients belong to the nonhyperdiploid variant MM (gray bar at the left indicates nonhyperdiploid MM) or the hyperdiploid variant MM (green bar at the left indicates hyperdiploid). Note the higher proportion of IgH translocations in the nonhyperdiploid group. Tetra indicates tetraploid.

These same associations were detected when patients were classified according to ploidy subcategories (Table 2). Remarkably, 16 (88%) of 18 patients with hypodiploidy had IgH translocations, and 9 (90%) of 10 patients with near-tetraploid karyotypes tested had an IgH translocation. When patients with near-tetraploid karyotype were excluded and the chromosome number was used as a continuous variable, the total chromosome number was significantly lower in patients with IgH translocations detected (median 45, range 40-66) than for patients without IgH translocations (median 52, range 41-64) (P < .0001).

Hypodiploid MM and IgH translocations. We used with cIg-FISH to further test the 7 (of 9) patients with hypodiploid MM and IgH translocations detected by the VH/CH strategy to identify the specific IgH translocations t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) and t(14;16)(q32; q23). Four of these patients (57%) had a t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) translocation, a higher prevalence than is commonly reported for this abnormality in unselected patients (approximately 15%).

ECOG patients

Prevalence of the abnormalities. When we extended our studies to the 199 patients entered into the ECOG E9486/E9487 clinical trial whom we had also studied for IgH translocations, Δ13, and DNA ploidy, the same results were observed (Table 3). The following prevalences were found: Δ13, 54% (108 of 199 patients tested); t(11;14)(q13;q32), 21% (41 of 197); t(4;14)(p16.3;q32), 16% (31 of 191); and t(14;16)(q32;q23), 5% (9 of 188). In addition, another 20% of patients (40 of 199) had an IgH translocation without an identifiable chromosome partner.

Among patients with Δ13, 19% had a t(11;14)(q13;q32) (20 of 106); 28% had a t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) (29 of 104); and 6% had the t(14;16)(q32;q23) (6 of 103). In addition, 17% of patients had an IgH translocation without an identifiable partner (81 of 108 patients with Δ13). Conversely, 94% of patients with a t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) had Δ13 (29 of 31), while 67% of patients with the t(14;16)(q32; q23) had Δ13 (6 of 9), and 49% of patients with a t(11;14)(q13;q32) had Δ13 (20 of 41). Of patients with an IgH translocation without an identifiable partner, 45% (18 of 40) had Δ13 too.

Ploidy analysis by DNA content and IgH translocations. Patients with IgH translocations were significantly more likely to have nonhyperdiploid MM than those without IgH translocations as detected by DNA content (68% versus 21%); in other words, hyperdiploid MM patients were less likely to have IgH translocations than others (39% versus 84%) (P < .001). When we compared the specific IgH translocation partners and ploidy subcategories, the same associations were observed (Table 4).

However, it appeared that the partners involved in the IgH translocations had a major effect on the association between ploidy and translocations. Among patients with an IgH translocation, patients with 1 of the 3 primary IgH translocations (t(4;14)(p16.3; q32), t(11;14)(q13;q32), or t(14;16)(q32;q23)) were significantly more likely to be in the nonhyperdiploid category compared with those identified as having a 14q32 translocation that was not specified (P < .001). As mentioned, DNA ploidy determination is not a reliable tool for detection of hypodiploidy, which explains the lower prevalence of hypodiploidy in this cohort.

Chromosome 13 (Δ13) and ploidy categories. We have previously reported of the association between the t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) and Δ13 in MM. We wished to investigate whether the same associations with ploidy seen for the IgH translocations were present for patients with Δ13. We found that Δ13 was significantly more common in patients with nonhyperdiploid MM (72% versus 37%, P < .001) (Table 5).

Discussion

Summary

Our study shows that 2 predominant cytogenetic subtypes of MM can be detected on the basis of the IgH translocations and total chromosomal complement: hyperdiploid MM with a low prevalence of IgH translocations, and nonhyperdiploid MM with a high prevalence of primary IgH translocations. Using multiple techniques, we report these associations in 2 independent cohorts of patients. While the associations were not absolute, there was a clear favoring for IgH translocations in the nonhyperdiploid variant MM.

We have also found that the specific partner involved in these IgH translocations is of great importance in determining the ploidy category of patients. Patients with the recurrent IgH translocations (t(4;14)(p16.3;q32), t(11;14)(q13;q32), and t(14;16)(q32;q23)) are highly favored in the nonhyperdiploid MM, while those without one of the recurrent chromosome partners do not share this association. These translocations have been proposed as primary by Kuehl and Bergsagel,2 because of the features that make them highly suspect for clonal immortalization. In contrast, some of the translocations that do not involve recurrent partners can represent secondary genetic events that may favor clonal expansion but may not necessarily be clone-initiation lesions.

We used slightly different cutoff values than have been reported for chromosome number in the karyotypes, as we thought our values better represented the underlying biology of the disease.5,7 These cutoff values are only slightly different from those commonly used for the classification of other diseases such as acute leukemia. When we took into consideration the actual prevalence of IgH translocations, defining pseudodiploid as those with 45 to 47 chromosomes was optimal. The associations were also present when we used the previously reported cutoff values, but the new ones resulted in a better biologic classification of patients.

Hypodiploidy and prognosis

The association of nonhyperdiploid MM and the recurrent IgH translocations raises the possibility that the previously observed negative effects on prognosis of hypodiploid MM may be due to the high incidence of “unfavorable” IgH translocations.6,7,10 We have previously observed that the hypodiploid MM category is highly associated with Δ13 as well as chromosome 14 monosomy.7 We now show here a high incidence of t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) among a small group of patients with hypodiploid MM. We and others have shown that patients with this translocation (and we also showed this for the t(14;16)(q32;q23)) have a significantly shortened survival.17,23,24 Hypodiploid MM is the global state associated with monosomies and is highly associated with a short survival.6,7,10,25 Of interest, hypodiploidy is also associated with inferior outcome in other neoplasias.26-28

Hyperdiploidy and prognosis

In contrast, it has been shown that patients with hyperdiploid MM have a more favorable outcome.22,29 In this study, we have found a prevalence of hyperdiploid of 34% among the Mayo patients and 51% among the ECOG patients. These numbers are comparable to what has been published in the literature and may reflect variations in the techniques, but are not fundamentally different. We have observed similar trends among patients studied by karyotype analysis.7 This improved prognosis probably relates to the absence of any of the adverse IgH translocations. We are also aware that in other neoplasms, such as in childhood leukemia, hyperdiploidy is associated with an improved outcome.30-32

Pathogenesis

Since clonal plasma cells without IgH translocations can be detected in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), it is logical to hypothesize that 2 major pathogenetic pathways result in the generation of plasma cell neoplasms. In the first one, an IgH translocation serves as the initial immortalizing event (nonhyperdiploid MM). Despite the presence of genomic instability, the karyotypes of these patients is more closely related to the normal 2N or the duplicated 4N complement. The second pathway, with a genetic lesion yet to be defined, is one that favors or allows the accumulation of extra copies of chromosomes. This pathway may have unique biologic features and a similar phenotype, and may be consistent with the presence of secondary IgH translocations. For instance, in leukemias, hyperdiploidy (in the absence of other structural chromosomal aberrations) is associated with a distinct gene-expression profile, suggesting a common underlying pathogenetic mechanism.33

t(11;14)(q13;q32)

While patients with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) were initially believed to have an unfavorable category of MM,34 recent work has confirmed their improved outcome.14,24 However, since the t(11;14)(q13;q32) is represented in up to 25% of human MM cell lines,35 it is possible that in some instances a clone with a t(11;14)(q13;q32) transforms to an aggressive phenotype after acquiring a secondary genetic “hit,” or that the clone has less dependence overall on the bone marrow microenvironment. Such secondary genetic mechanisms could include p16 inactivation by promoter methylation.36

Relation to the human MM cell lines

The vast majority of the human MM cell lines harbor IgH translocations.37,38 Thus, these cell lines probably originate from the nonhyperdiploid form of MM. Because of the requirements for MM cells to grow ex vivo, it seems reasonable to postulate that IgH translocations provide a proliferation (and perhaps survival) advantage to the clone. This advantage in turn translates into a clone that has the potential to achieve bone marrow emancipation. A possible explanation is that the transcriptional effect of the oncogenes up-regulated by IgH translocations replaces the need for growth factors provided by the marrow microenvironment. This is further supported by the finding of a high incidence of IgH translocations (80%) in the most aggressive MM variant, plasma cell leukemia. Human MM cell lines that represent hyperdiploid MM, not harboring IgH translocation, are needed to complement the current repertoire of human MM cell lines. In support of our global observations, we also note that patients with plasma cell leukemia usually have nonhyperdiploid MM.39-42 When these patients are studied by DNA content, they are usually nonhyperdiploid.43

Association of ploidy categories with Δ13

The same associations exist between ploidy categories and Δ13 in that loss of a copy of chromosome 13 was significantly more common in patients with nonhyperdiploid variant MM. This also is consistent with previous observations on the association between the t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) and Δ13 and also between the t(14;16)(q32;q23) and Δ13. Discerning the effects of IgH translocations versus those emanating from the loss of a copy of chromosome 13 will be important in understanding the contribution for the negative prognosis of hypodiploid MM. Because the actual prevalence of Δ13 (best determined by interphase FISH) is much greater than that of t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) and t(14;16)(q32;q23), we suspect the contribution for a poor outcome in the hypodiploid MM is more likely related to these aggressive translocations and not to the loss of chromosome 13.

Biology of association

There is no immediate explanation for the observed association between IgH translocations and nonhyperdiploid MM. We speculate that the survival advantage provided by IgH translocations, in the context of ongoing genomic instability, is permissive to chromosomal losses until a certain critical point (crisis or limit). Conversely, in patients without IgH translocations, but still in the context of genomic instability, the karyotype evolution favors hyperdiploidy and is less tolerant toward chromosomal loss. This hypothesis is in need of further study, but would provide the best rationale for targeting translocations for the treatment of nonhyperdiploid MM. If the hypothesis is true, the cells may be heavily burdened by chromosomal loss that can be sustained only because of the IgH translocation proliferative signaling. This would imply that the mere down-regulation of genes involved in IgH translocations may be sufficient to promote apoptosis or sensitize the cells to therapy agents.

Conclusion

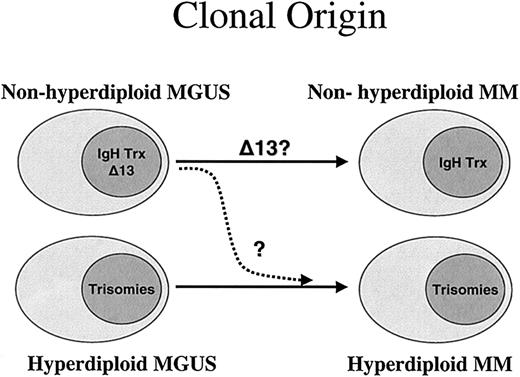

The results presented here are in agreement with the published literature on chromosomes and MM. The following unifying concepts appear to be recurrent and consistent. First, MM is composed of several subgroups that are best characterized by the specific genetic lesions of the clonal plasma cells. The patterns of karyotype aberrations seen in MM are not random (Figure 2). Two major subgroups of MM can be discerned: hyperdiploid MM and nonhyperdiploid MM. We now show they are closely related to the presence of the primary IgH translocations. The close association of unfavorable IgH translocations with hypodiploid variant MM is a probably a major contributor to the adverse outcome observed in these patients.

Hypothesis for the 2 pathogenesis pathways for MM. According to our results, the natural hypothesis is to postulate 2 fundamentally separate pathways for the pathogenesis of MM. This hypothesis is based on the close relationship of ploidy category to the presence of the recurrent IgH translocations. While most patients in the nonhyperdiploid group have IgH translocations, patients in the hyperdiploid group have more trisomies, and both conditions might arise from similar clones observed at the MGUS stage. Each of the 2 pathways could be independent, but it is possible that in some cases the nonhyperdiploid could lose an IgH translocation and give rise to the hyperdiploid variant MM (dashed arrow). It is currently unknown if this ploidy and IgH association is also seen in MGUS.

Hypothesis for the 2 pathogenesis pathways for MM. According to our results, the natural hypothesis is to postulate 2 fundamentally separate pathways for the pathogenesis of MM. This hypothesis is based on the close relationship of ploidy category to the presence of the recurrent IgH translocations. While most patients in the nonhyperdiploid group have IgH translocations, patients in the hyperdiploid group have more trisomies, and both conditions might arise from similar clones observed at the MGUS stage. Each of the 2 pathways could be independent, but it is possible that in some cases the nonhyperdiploid could lose an IgH translocation and give rise to the hyperdiploid variant MM (dashed arrow). It is currently unknown if this ploidy and IgH association is also seen in MGUS.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 12, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0493.

Supported in part by Public Health Service grant no. R01 CA83724-01 (R.F.) and P01 CA62242 (R.A.K., P.R.G.) from the National Cancer Institute and by the Fund to Cure Myeloma. P.R.G. is supported by the ECOG grant CA21115-25C from the National Cancer Institute. R.F. is a Clinical Investigator of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.