There are intimate, multiple, and complex interrelationships between the plasminogen/fibrinolytic system and cancer. The more than 4000 publications in PubMed since 1965 attest to these linkages. These publications include many studies that correlate the levels of individual components of the plasminogen system; plasminogen activators (tissue-type plasminogen activator [tPA] and urokinase-type plasminogen activator [uPA]); plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAI-1) and fibrinogen/fibrin degradation products; and the prognosis of particular types of cancer. Other studies focus on the role of the plasminogen system and its activities in regulating the growth and metastasis of tumor cells. Some of these publications even report efforts to therapeutically target the activity of the plasminogen system to influence tumor progression. Occasionally, some rather striking and unexpected results are described. Included in this category would be the discovery of angiostatin, an inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis, as a degradation product of plasminogen. This finding stimulated an explosion of reports attempting to define the basis of angiostatin formation, the mechanism of its antiangiogenic activity, and the search for other antiangiogenic activities.FIG1

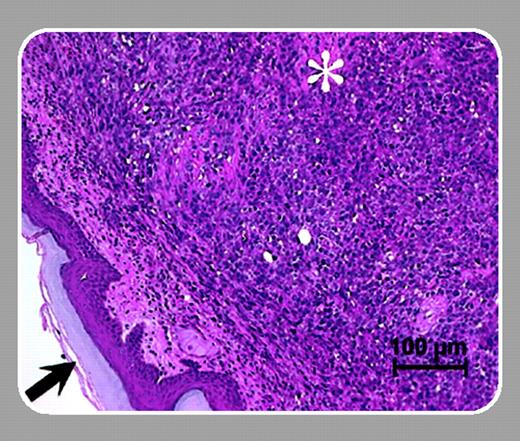

Falling into this category of unexpected findings is the article by Palumbo and colleagues (page 2819). These investigators report that the plasminogen deficiency dramatically suppresses the growth of tumors transplanted into one anatomic location, the footpads, but not into another, the dorsal skin. This comparison is made by comparing tumor growth in these anatomic locations of wild-type and plasminogen-deficient mice, and the difference in growth is observed with 2 unrelated tumors. When the experiment was performed in mice that were not only deficient in plasminogen but also in fibrinogen, tumor growth in the footpads was no longer suppressed. Histologic examination of the tissue of the footpads from the plasminogen-deficient mice showed substantial fibrin deposition and vaso-occlusive thrombi, which may limit the requisite blood supply to the developing tumor to support its rapid growth. Various studies have identified both fibrin-dependent and fibrin-independent abnormalities in the plasminogen-deficient mouse. The differences in tumor growth appear to fall into the former category.

Many investigations have emphasized the importance of location—the tumor microenvironment—in supporting the growth and metastasis of tumors. The study by Palumbo et al provides a clear example of how the hemostatic status of a tissue can determine tumor growth and how this status can vary in different anatomical locations. The article also can be taken as support for the evolving idea that local thrombosis may be an effective therapy for the ablation of tumors.