Abstract

We have applied a proteomics approach to analyze signaling cascades in human platelets stimulated by thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP). By analyzing basal and TRAP-activated platelets using 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE), we detected 62 differentially regulated protein features. From these, 41 could be identified by liquid chromatography–coupled tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and were found to derive from 31 different genes, 8 of which had not previously been reported in platelets, including the adapter downstream of tyrosine kinase 2 (Dok-2). Further studies revealed that the change in mobility of Dok-2 was brought about by tyrosine phosphorylation. Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation was also found to be involved in collagen receptor, glycoprotein VI (GPVI), signaling as well as in outside-in signaling through the major platelet integrin, αIIbβ3. These studies also provided the first demonstration of posttranslational modification of 2 regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins, RGS10 and 18. Phosphorylation of RGS18 was mapped to Ser49 by MS/MS analysis. This study provides a new approach for the identification of novel signaling molecules in activated platelets, providing new insights into the mechanisms of platelet activation and building the basis for the development of therapeutic agents for thrombotic diseases.

Introduction

Platelets are enucleated cells that circulate in the blood playing a key role in the control of bleeding. Under pathologic circumstances, platelets are involved in the generation of thrombotic disorders and in development of heart disease.1 Thrombin is one of the most powerful platelet-activating agents.2 Thrombin activation in human platelets is mediated by the proteinase-activated receptors, PAR-1 and PAR-4, which belong to a family of G protein–coupled receptors (GPC-R).3-5 PAR-1 plays the predominant role.6 Cleavage of PAR-1 by α-thrombin yields a new amino terminus with the initial sequence SFLLRN, which serves as an agonist. This peptide sequence, termed thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP), is also able to activate the noncleaved receptor and replace thrombin in in vitro experiments allowing for controlled cell stimulation.2,7,8 Signaling by PAR-1 has been extensively studied.7,9,10 However, a full picture of all of the signaling molecules in the PAR-1 pathway is not available. This information is important to fully understand the events underlying platelet activation by PAR-1 and for identification of potential drug targets and future therapeutic modulation of platelet activation processes.

In order to gain a better insight into the signaling events following PAR-1 receptor stimulation, we analyzed the proteome of platelets activated by TRAP and compared it with that of unstimulated platelets. Such proteome analysis involves the separation and characterization of hundreds to thousands of proteins at a time. The strategy is based on the key technologies of 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) and liquid chromatography (LC) followed by mass spectrometric (MS) protein analysis.11-13 This approach of directly analyzing the proteins involved and their posttranslational modifications is very powerful for the dissection of signaling events in platelets. Building on our extensive experience with the platelet proteome14,15 and using narrow isoelectric point (pI) range 2-DE gel electrophoresis for differential proteome analysis, we report here the identification of new proteins and signaling events in platelets triggered by PAR-1 receptor stimulation.

Materials and methods

Reagents and suppliers

TRAP was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Purified convulxin, isolated from the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus as described,16 was a gift from Drs M. Leduc and C. Bon (Unite des Venens, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). Collagen (Horm) was purchased from Nycomed (Munich, Germany). Thrombin was purchased from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom). Lotrafiban was supplied by GlaxoSmithKline (King of Prussia, PA). The αIIb-deficient mice were bred from heterozygotes and compared with littermate controls as described.17,18 Unless specifically stated, the suppliers of other chemicals and instruments were the same as described previously.14

Platelet preparation and activation with TRAP

Fresh blood was collected from healthy volunteers who had not been on medication for the previous 10 days. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Central Oxford Research Ethics Committee (No:00.231). Each blood sample was processed individually and mixed with a 4% (wt/vol) sodium citrate stock solution (Sigma) to a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol) of the anticoagulant. Platelet isolation was carried out as described previously.14 Resulting platelet pellets were resuspended in Tyrodes-HEPES (134 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 5 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA [ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid], pH 7.3) at 1 × 109 platelets/mL and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. In a limited study involving aggregation, EGTA was omitted or the αIIbβ3 antagonist lotrafiban was included. For TRAP activation, 1 mL platelet aliquots were warmed to 37°C in a water bath for 10 minutes. Each aliquot was stimulated by 5 μM TRAP while stirring (1200 g) for 30 seconds at 37°C. For unstimulated samples, the procedure was adjusted by adding 10 μL tris-buffered saline (TBS) without TRAP. Following stimulation, cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Mice platelets were isolated and resuspended in Tyrodes-HEPES as previously described.18

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Proteins were extracted from frozen platelet suspensions, taking care to minimize protein degradation. All reagents were chilled to 4°C and extraction was carried out on ice. Five microliters of a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (consisting of equal quantities of 100 mM sodium fluoride, 1 M sodium orthovanadate, and 1 M benzamidine) and 20 μL of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO) were added to each 1-mL platelet sample. Five hundred microliters of 60% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in acetone was then added and the sample sonicated briefly until it was completely melted (30 seconds on an 80% duty cycle at 25% power; Status 70 MS73 with SH70G tip; Philip Harris Scientific; Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire, UK). The sample was left on ice for 45 minutes, centrifuged at 10 000g for 2 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. Protein pellets were then washed twice with acetone. For pI 4-7 2-DE gels, pellets were resuspended in 375 μL sample buffer (5 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2 mM tributyl-phosphine, 65 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 65 mM CHAPS [3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propane-sulfonic acid], 0.15 M dimethylbenzene ammonium propane sulfonate (NDSB) 256, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM benzamidine). For pI 6-11 2-DE gels, protein pellets were resuspended in 500 μL of same sample buffer containing 10% isopropanol. Ampholytes (Servalyte 4-7 and 6-11) were added to the sample to a final concentration of 1.5% (vol/vol). The 2-DE gel electrophoresis was carried out as described previously.14 Following electrophoresis, the gels were fixed in 40% (vol/vol) ethanol:10% (vol/vol) acetic acid and stained with the fluorescent dye OGT MP17 (Oxford GlycoSciences, Abingdon, UK) on the basis of Hassner et al.19 Sixteen-bit monochrome fluorescence images were obtained at 200 μm resolution by scanning gels with an Apollo II linear fluorescence scanner (Oxford GlycoSciences).

Differential image analysis

Scanned images were processed with a custom version of MELANIE II (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). Four pI 4-7 gels and 4 pI 6-11 gels were prepared in independent experiments for both basal and TRAP-activated platelets. Internal calibration of the 2-DE gel images with regard to pI and molecular weight was carried out as described previously.14

For differential image analysis, 2 synthetic gel images, one for each of the 2 applied analytical pI ranges of 4-7 and 6-11, were generated by means of accurate spot matching. These synthetic images contained all protein features detected in basal and stimulated platelets. Only features present in at least 3 of 4 individual gels belonging to either the basal or TRAP group were considered for differential analysis. Intensity (optical density) was measured by summing pixels within each spot boundary (spot volume) and recorded as a percentage of the total spot intensity of the gel: %V = spot volume/Σ volumes of all spots resolved in the gel. Variations in protein expression were calculated as the ratio of average volumes (%V) and carefully validated by repeated image analysis by human operators. Differential expression of a protein present in both the basal and TRAP gels was considered significant when fold change was at least 2 and P was no more than .05 after rank sum test applied on %V values.

In-gel digestion and peptide extraction

Protein features chosen for mass spectrometric analysis were excised from the gels by a software-driven robotic cutter (Oxford Glycosciences, Abingdon, United Kingdom). The recovered gel pieces were dried in a speed-vac. In-gel digestion with trypsin and peptide extraction were carried out by the automated DigestPro workstation (Abimed, Langenfeld, Germany) according to the protocol of Shevchenko et al.20 The combined fractions were lyophilized and dissolved in 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid.

Mass spectrometric analysis

Mass spectrometric analysis was carried out using Q-TOF (Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom) coupled with CapLC (Waters, Milford, MA). The tryptic peptides were loaded and desalted on a 300 μm internal diameter/5 mm length C18 PepMap column (LC Packings, San Francisco, CA). The peptide mixture was eluted with 80% to 95% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid over 20 minutes at a flow rate of 200 nL/minute. Mass data acquisitions were piloted by Masslynx software (Micromass) using automatic switching between MS and coupled tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) modes. The survey scan (1s) was obtained over the mass range of m/z 300 to 1200 in the positive ion mode with a cone voltage of 40 V. When the signal reached a user-defined threshold (10 counts/s), peptide precursor ions could be selected for MS/MS scan (2s) over the mass range m/z 50-2000. Fragmentation was performed using argon as the collision gas and with a collision energy profile (20-40 eV) optimized for various mass ranges of precursor ions. The selected precursor ions were automatically included in the exclusion list. The database search was performed with the MASCOT search tool (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) screening SWISS-PROT restricted to human taxonomy.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Basal and TRAP-stimulated platelets (8 × 108/mL, 500 μL) were lysed by adding an equal volume of ice-cold 2× lysis buffer (2% [vol/vol] nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 20 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1 mM [4-(2-aminoethyl)–benzenesulfonyl fluoride (ABSF)], 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, pH 7.3). Alternatively, washed platelets (5 × 108/mL), in the presence or absence of lotrafiban (10 μM), were stimulated with thrombin (1.0 U/mL, for 90 s), convulxin (3 μg/mL, for 2 minutes), or Horm collagen (10 μg/mL, for 2.5 minutes) prior to addition of equal volume of 2× lysis buffer. Washed murine platelets obtained from wild-type (C57BL/6) or αIIb-deficient mice were stimulated with thrombin (1.0 U/mL, for 90 s), convulxin (3 μg/mL, for 2 minutes), or Horm collagen (10 μg/mL, for 2.5 minutes) prior to addition of equal volume of 2× lysis buffer. Four micrograms of rabbit Dok-2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or 5 μg of a monoclonal mouse antiphosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to agarose (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were then added and samples rotated overnight at 4°C. Twenty microliters of protein G–Sepharose (50% [wt/vol] in TBS-T [Tris-buffered saline plus Tween 20: 20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% {vol/vol} Tween 20, pH 7.6]) was added to Dok-2 immunoprecipitated samples, which were rotated again at 4°C for 1 hour. Pellets were washed once in 1× lysis buffer and 3 times in TBS-T before addition of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (4% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 50 mM Tris, pH 6.8).

Proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% gels and transferred on to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked in 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA): TBS-T (wt/vol) overnight at 4°C. The blots were then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature using as primary antibodies either rabbit anti–Dok-2 (1:200) or mouse antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (mAb; 4G10; 1:1000). Following washes in TBS-T, the blots were incubated for 1 hour with horseradish peroxidase–labeled antirabbit or antimouse polyclonal antibody (1:10 000), respectively. Membranes were washed again and developed using an enhanced-chemiluminescence system (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Cardiff, United Kingdom). Whenever necessary, blots were stripped by incubation for 30 minutes at 80°C in stripping buffer (TBS-T, 2% [wt/vol] SDS and 1% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol) and reprobed.

Results

Differential proteome analysis of basal and TRAP-activated platelets by 2-DE

We first optimized the experimental conditions for platelet stimulation, protein extraction, and protein separation by 2-DE (data not shown). Platelet stimulation using 5 μM TRAP for 30 seconds led to powerful platelet activation (not shown). Using 1 × 109 platelets in 1 mL of Tyrodes-HEPES buffer, which contained EGTA to prevent aggregation, we were able to obtain more than 1 mg protein for subsequent 2-DE analysis (Figure 1). Protein extraction by cell lysis in liquid nitrogen followed by TCA/acetone precipitation and delipidation resulted in highly reproducible 2-DE proteome maps demonstrating efficient prevention of proteolytic processes and other experimental variations that could potentially lead to irreproducible proteome maps.14,15 The experimental conditions resulted in high-resolution 2-DE gels for both the 4-7 and 6-11 narrow-range pH gradients (Figure 2). In consequence, a mean of 692 (± SE26) and 377 (± SE53) protein features were found in basal platelets on pI 4-7 gels and pI 6-11 gels, respectively.

Experimental design for the differential analysis approach. Proteins were extracted from basal and TRAP-activated platelets and resolved in pI 4-7 and pI 6-11 2-DE gels. After detailed differential image analysis between the different sets of gels, indicated in the figure by double-headed arrows, variant spots were excised and digested. Proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS.

Experimental design for the differential analysis approach. Proteins were extracted from basal and TRAP-activated platelets and resolved in pI 4-7 and pI 6-11 2-DE gels. After detailed differential image analysis between the different sets of gels, indicated in the figure by double-headed arrows, variant spots were excised and digested. Proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS.

Synthetic 2-DE gel images representing all protein features present in the basal versus TRAP analysis. (A) pI 4-7 range. (B) pI 6-11 range. The figure shows the location on the 2-DE gels of the differential regulated protein features, how intense these features are, and where the successfully identified ones are located. Representative gels from control and stimulated platelets have not been superimposed on each other but rather each synthetic image is representative of the group of 8 gels (4 basal and 4 TRAP) for the 2 pH ranges. The original gels were used for the differential analysis. The differentially regulated features are indicated and identified labeled with their SWISS-PROT and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession number. B indicates protein feature only present in basal gels; T, protein feature only present in TRAP gels; B*, protein feature present in both basal and TRAP gels, expressed to a higher extent in the basal sample; and T*, protein feature present in both basal and TRAP gels, expressed to a higher extent in the TRAP stimulated sample. Further information on this figure will be available at our web site (http://www.bioch.ox.ac.uk/glycob/ogp/blood03.html).

Synthetic 2-DE gel images representing all protein features present in the basal versus TRAP analysis. (A) pI 4-7 range. (B) pI 6-11 range. The figure shows the location on the 2-DE gels of the differential regulated protein features, how intense these features are, and where the successfully identified ones are located. Representative gels from control and stimulated platelets have not been superimposed on each other but rather each synthetic image is representative of the group of 8 gels (4 basal and 4 TRAP) for the 2 pH ranges. The original gels were used for the differential analysis. The differentially regulated features are indicated and identified labeled with their SWISS-PROT and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession number. B indicates protein feature only present in basal gels; T, protein feature only present in TRAP gels; B*, protein feature present in both basal and TRAP gels, expressed to a higher extent in the basal sample; and T*, protein feature present in both basal and TRAP gels, expressed to a higher extent in the TRAP stimulated sample. Further information on this figure will be available at our web site (http://www.bioch.ox.ac.uk/glycob/ogp/blood03.html).

Following platelet stimulation by TRAP, the number of resolved protein features dramatically increased by 138 and 95 features to 830 (± SE20) and 472 (± SE21) for the pI 4-7 and 6-11 analytical ranges, respectively. This elevation in features indicates effective stimulation by TRAP and an associated increased complexity of the platelet proteome.

To identify TRAP-induced changes in the platelet proteome, image analysis of 4 independent experiments was performed as shown in Figure 1. We focused on the identification of disappearing and appearing spots, as well as up- and down-regulation of spot intensities where the fold change was at least 2 (with P ≤ .05). Further, approximately 70% of protein features were present in at least 3 of the 4 gels per group (basal or TRAP), which was the requirement for being considered for the analysis. These conservative criteria for protein detection aimed to avoid misidentifications due to gel-to-gel variations. Applying these criteria, 62 differentially regulated protein features were identified. Thirty-four of these were found in the pI 4-7 analytical range, with 18 being up-regulated and 16 down-regulated (Figure 2A). In the pI 6-11 range, 8 proteins were up-regulated and 20 down-regulated (Figure 2B).

Forty-one (66%) of the 62 differentially expressed proteins were successfully identified by LC-MS/MS. They correspond to 31 different open reading frames (ORFs) (Table 1; Figure 2), with 6 ORFs being represented by multiple protein spots. A number of features were either lost or appeared upon stimulation. Fourteen proteins present on basal gels were not detectable following TRAP stimulation, and 8 proteins could not be identified on basal gels but were found on TRAP-stimulated gels. The other 19 protein features were present on both basal and TRAP-stimulated gels, but 9 showed a significantly higher level of intensity under basal conditions and 10 after stimulation with TRAP.

Examples of changes in some of the features, along with their identity, are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3A-B illustrates 2 sets of features that appear upon stimulation. In Figure 3A, a weak feature, identified as integrin-linked protein kinase-2 (ILK-2), is seen to undergo a marked increase in intensity upon stimulation. In Figure 3B, an array of features is seen under basal conditions that shifts to the left and elongates upon stimulation. These features were identified as pleckstrin, the major substrate for protein kinase C in platelets.21 Pleckstrin has 6 phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C,22 consistent with the presence of the multiple features. Figure 3C and D illustrate 2 features that disappear upon activation; these features correspond to Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) and regulator of G protein signaling 10 (RGS10), respectively.

Close-up images of representative 2-DE gel images showing changes in signaling proteins that have been identified by differential analysis. (A) ILK-2. (B) Pleckstrin. (C) RKIP. (D) RGS10. B indicates 2-DE gel corresponding to basal platelets; and T, 2-DE gel corresponding to TRAP-activated platelets (5 μM, 30 s). Circled areas indicate the differentially regulated protein feature.

Close-up images of representative 2-DE gel images showing changes in signaling proteins that have been identified by differential analysis. (A) ILK-2. (B) Pleckstrin. (C) RKIP. (D) RGS10. B indicates 2-DE gel corresponding to basal platelets; and T, 2-DE gel corresponding to TRAP-activated platelets (5 μM, 30 s). Circled areas indicate the differentially regulated protein feature.

Functional analysis and significant proteins detected

Many of the identified proteins belong to one of the following 3 groups of proteins: cytoskeletal, signaling, and protein processing (Table 1). The list of cytoskeletal proteins comprises actin, destrin, tropomyosin α 4 chain, myosin regulatory light chain 2, 36 kDa c-terminal LIM domain protein (CLP-36), and transgelin 2. Six of the proteins affected by TRAP stimulation are involved in biosynthesis and protein degradation (Table 1). Platelets possess a very limited capacity for protein synthesis, which is of uncertain physiologic significance. In addition, the presence of these features might represent a carry over from megakaryocytes. In any case, it is necessary to bear in mind that protein modifications after powerful platelet activation do not always imply a functional correlation. Further work is required to establish the precise role of these proteins in the context of platelet activation.

Among the 31 ORFs identified, 8 were known signaling proteins. This constitutes the main group in the functional analysis, representing 37% of the total number of features identified, several of which correspond to forms of pleckstrin (Table 1; Figure 3B). The identified signaling proteins are pleckstrin, ILK-2, RKIP, RGS10, RGS18, 14-3-3-γ, Dok-2, and heat shock protein 27 (HSP27). Many of the cytoskeletal proteins could also be classified as part of the signaling group on the grounds that their activity is regulated by phosphorylation, including myosin light chain and CLP-36. Some of the signaling proteins have been previously described in platelets but were not known to undergo phosphorylation, including RGS10 and RGS18, whereas for others this is the first description of their presence in platelets, including the adapter Dok-2 and RKIP. This study has also identified a number of nonsignaling proteins whose presence in platelets is reported for the first time, namely transgelin 2, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 N, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERp29), mannose-6-phosphate isomerase, D-prohibitin, and the hypothetical protein Q96GF6. This latter is a possible small magnesium-dependent phosphatase, which had so far existed in databases on the basis of an ORF prediction from cDNA sequences.

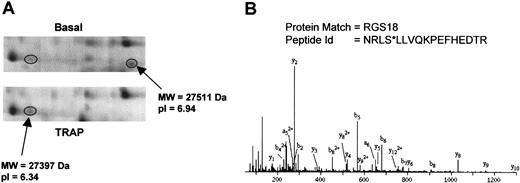

RGS18 phosphorylation

RGS18 was represented in our analysis by 2 protein features separated by 0.6 pI units (Figure 4A). The disappearance of the protein feature at pI 6.94 together with the increase at pI 6.34 strongly suggests that RGS18 is phosphorylated to a high stoichiometry in response to PAR-1 receptor stimulation by TRAP. Further, the extent of this shift suggests that RGS18 is phosphorylated at more than one site. MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peptides for RGS18 revealed phosphorylation at Ser49 on the feature at pI 6.34 (Figure 4B). The MS/MS spectrum for the peptide NRLSLLVQKPEFHEDTR (m/z = 541.24, quadruply charged) showed a high confidence-matching pattern for the presence of y- and b-ions originating from this peptide. Masses corresponding to the respective b4 ion and successive ones (b5-b9), in line with the detected a-ions, were consistent with the loss of a phosphate group at Ser49 (Figure 4B).

RGS18 phosphorylation induced by TRAP. (A) 2-DE gel images showing the RGS18 features. (B) MS/MS spectrum of the ion at m/z 541.24 (4+), corresponding to NRLS*LLVQKPEFHEDTR (* indicates phosphorylated). All the b and a ions presented in the spectrum (except b2) appear after the loss of 98 Da from the phosphate group during fragmentation.

RGS18 phosphorylation induced by TRAP. (A) 2-DE gel images showing the RGS18 features. (B) MS/MS spectrum of the ion at m/z 541.24 (4+), corresponding to NRLS*LLVQKPEFHEDTR (* indicates phosphorylated). All the b and a ions presented in the spectrum (except b2) appear after the loss of 98 Da from the phosphate group during fragmentation.

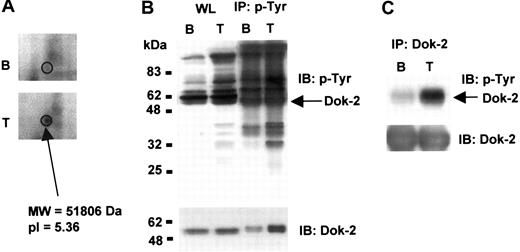

Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation

Dok-2 was detected as a feature that is up-regulated upon TRAP stimulation (Figure 5A). However, we did not identify a corresponding Dok-2 feature that was down-regulated, most likely because it underwent less than a 2-fold decrease, the cutoff for selection. Dok-2 has been previously shown to be phosphorylated on tyrosine in other cells.23 To investigate whether Dok-2 undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation in platelets, we carried out immunoprecipitation and Western blot analyses on basal and TRAP-stimulated platelets. TRAP stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of a number of bands in platelets, as illustrated by Western blotting the whole cell lysate using the antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 or following immunoprecipitation using 4G10 and Western blotting with the same antibody (Figure 5B). Western blotting 4G10-immunoprecipitated proteins with an anti–Dok-2 antibody showed an increase in the amount of precipitated Dok-2 after platelet activation with TRAP, which had a reduction mobility relative to Dok-2 present in the whole cell lysate as expected for phosphorylation (Figure 5B). When platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti–Dok-2 antibody and probed with an antibody to phosphotyrosine, we observed a significant increase in Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation levels after TRAP stimulation (Figure 5C), confirming that the adapter is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in response to activation of PAR-1.

Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation induced by TRAP. (A) 2-DE gel representative image showing up-regulation of a Dok-2 protein feature upon TRAP stimulation. (B) Whole protein lysate and phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitated proteins or (C) Dok-2 immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine or anti–Dok-2 antibodies. B indicates basal; T, TRAP (5 μM, 30 s); IP, immunoprecipitation; and IB, immunoblot. Images represent at least 3 independent experiments.

Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation induced by TRAP. (A) 2-DE gel representative image showing up-regulation of a Dok-2 protein feature upon TRAP stimulation. (B) Whole protein lysate and phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitated proteins or (C) Dok-2 immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine or anti–Dok-2 antibodies. B indicates basal; T, TRAP (5 μM, 30 s); IP, immunoprecipitation; and IB, immunoblot. Images represent at least 3 independent experiments.

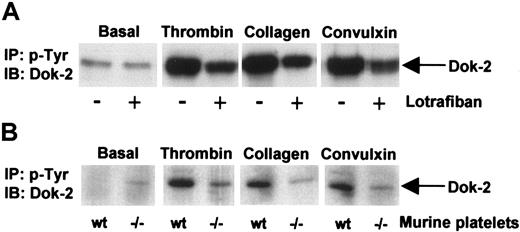

Since this is the first description of a member of the Dok or related insulin receptor substrates (IRS) family of proteins in platelets, studies were designed to investigate whether Dok-2 is also regulated by other platelet agonists. The data in Figure 6 demonstrate that phosphorylation of Dok-2 by thrombin is markedly potentiated under aggregating conditions as revealed by the inhibitory effect of the αIIbβ3 antagonist, lotrafiban, and by studies on αIIb-deficient mice. Dok-2 also undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation in human platelets in response to stimulation by collagen and by the glycoprotein VI (GPVI)–specific snake toxin, convulxin, and this is also potentiated under aggregating conditions (Figure 6). These results demonstrate that Dok-2 is tyrosine phosphorylated in response to activation of thrombin and collagen receptors but that the extent of phosphorylation is markedly potentiated by outside-in signaling via the integrin αIIbβ3.

Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation induced by activation of thrombin and collagen receptors. Role of outside-in signaling via the integrin αIIbβ3. Phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitated proteins from human (A) or murine (B) platelets were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using anti–Dok-2 antibodies. Platelets were activated with thrombin (1.0 U/mL, 90 seconds), convulxin (3 μg/mL, 2 minutes), and collagen (10 μg/mL, 2.5 minutes). (A) Platelets were activated in the presence or absence of the αIIbβ3 antagonist lotrafiban (10 μM). (B) Wt indicates wild-type mice; –/–, αIIb-deficient mice; IP, immunoprecipitation; and IB, immunoblot. Images represent at least 3 independent experiments.

Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation induced by activation of thrombin and collagen receptors. Role of outside-in signaling via the integrin αIIbβ3. Phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitated proteins from human (A) or murine (B) platelets were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using anti–Dok-2 antibodies. Platelets were activated with thrombin (1.0 U/mL, 90 seconds), convulxin (3 μg/mL, 2 minutes), and collagen (10 μg/mL, 2.5 minutes). (A) Platelets were activated in the presence or absence of the αIIbβ3 antagonist lotrafiban (10 μM). (B) Wt indicates wild-type mice; –/–, αIIb-deficient mice; IP, immunoprecipitation; and IB, immunoblot. Images represent at least 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

We have investigated the proteome of platelets activated by the PAR-1–selective peptide TRAP to identify new proteins that are regulated during platelet activation. In these studies, outside-in signaling by the integrin αIIbβ3 was inhibited by inclusion of EGTA. Inhibitors of the feedback mediators, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2, were not included so as to increase the chance of identifying new proteins.

The 2-DE gel–based proteomic strategy offers a reproducible high-resolution protein separation method as the basis for differential proteome analysis. Narrow-range immobilized pH gradient strips were used during isoelectric focusing to increase the number of proteins resolved.24,25 Experimental artifacts and major proteolysis were avoided as demonstrated by the unchanged expression levels of the majority of proteins. We detected 62 features that underwent at least a 2-fold change in intensity upon platelet stimulation with TRAP. We were able to identify 41 of the 62 features, corresponding to 31 ORFs. Reasons for our failure to detect the other 21 features include a low level of expression, peptide hydrophobicity, and absence from available databases. A conservative 2-fold change in intensity was selected to avoid differences that were due to other factors, such as differences between gels. It is important to recognize however that this may have lead to an underestimate of the number of proteins that are differentially regulated in the activated platelets.

It is important to emphasize that 2-DE electrophoresis is not an absolute separation technology in the sense that not all proteins are fully resolved from each other on the gel and that not all proteins are present on the gel. As a consequence, this is also likely to have lead to an underestimation of the number of differentially regulated proteins. Specific concerns include the following: (1) nondetection of a relevant feature due to the pI of the protein being outside the experimentally chosen analytical pH window; (2) a differentially regulated protein accounting not being detected because of comigration with proteins that are present at a much higher level; (3) failure of a protein to enter the gel; and (4) the protein may be represented by an array of 2 or more spots due, for example, to limited phosphorylation under basal conditions; as a consequence, changes in spot volume could be below the selected threshold of 2-fold. The 2-DE approach should therefore be used in combination with other approaches to address some of these concerns, although it should be emphasized that other approaches will also have their limitations.

We were particularly interested in those proteins that were differentially regulated by phosphorylation, as this represents the major way of posttranslation modification of proteins in a stimulated cell. Consistent with this, a higher number of up-regulated features were found on pI 4-7 gels after TRAP stimulation, whereas there were more down-regulated features on pI 6-11 gels under these conditions. A change in the proteome map of this nature is consistent with a shift of proteins toward a more acidic pI due to phosphorylation. One of these differentially regulated proteins is pleckstrin, which gives rise to several features as illustrated in Figure 3B. Pleckstrin has been previously reported to be phosphorylated in platelets in response to TRAP.26 We also detected other proteins that have been shown to undergo phosphorylation in response to TRAP stimulation, including HSP2727 and myosin light chain.28 The fact that we have found these proteins in our analysis supports the validity of our experimental approach.

It is of interest to compare the present approach with that used by Maguire et al,29 who analyzed the phosphotyrosine proteome of thrombin-activated platelets by matrix-assisted laser desorption time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry and Western blotting. They found 67 proteins to be unique in the thrombin-activated platelet proteome when compared with resting platelets. From these 67 proteins, they identified 10, including the fibrinogen β chain, which was also found in our analysis. The approach used by Maguire et al was distinct from the one that was used in our study because they prefractionated their samples through immunoprecipitation using antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, thereby focusing their work on protein complexes that were composed of one or more proteins that had undergone tyrosine phosphorylation. It is possible, for example, that some of the immunoprecipitated proteins may not have been phosphorylated but simply recruited into complexes with other proteins. Such a protein would not have been detected in the approach used in our study. The approaches used by Maguire et al and by us are complementary and illustrate the power of proteomics to provide new information in activated platelets.

As for the NetPhos 2.0 server,30 all the proteins identified in our analysis have some serine, threonine, or tyrosine theoretical phosphorylation site (data not shown). It is, therefore, interesting to discuss the functional role of some of these phosphorylated proteins. Pleckstrin phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC), for example, is known to be implicated in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton, a well-known consequence of platelet activation.31 We also detected the scaffolding protein 14-3-3-γ, which is implicated in the regulation of the cytoskeleton. It has also been reported that 14-3-3-γ inhibits the enzymatic activity of PKC in platelets.32 In other cell types, 14-3-3-γ has been shown to interact with PKC and Raf-1 (located downstream of PKC in the mitogen-activated protein [MAP] kinase pathway), providing a link between these 2 proteins.33 In addition, and for the first time in platelets, we identified the Raf-1–related protein RKIP, which interacts with and inhibits Raf-1.34 Phosphorylation of RKIP by PKC causes its release from Raf-1 and up-regulation of extracellular-signal regulated kinases (ERKs).35 We further confirmed the presence of ILK-2, a receptor-proximal protein kinase known to be autophosphorylated on serine residues,36 in platelets. This protein may act as a mediator of inside-out or outside-in integrin signaling.

Of particular interest in this study was the identification of signaling proteins that were not previously known to be regulated by phosphorylation. For example, we found 2 members of the RGS family, RGS10 and RGS18, to be differentially regulated after TRAP stimulation. RGS proteins are directly linked to GPC-R and inhibit signal transduction by increasing the guanosine 5′-triphosphatase (GTPase) activity of G protein α subunits, thereby driving them into their inactive guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP)–bound form.37 RGS10 and RGS18 have been previously reported in platelets, with RGS18 being particularly enriched38 and RGS10 being highly expressed in bone marrow.39 Human RGS18 selectively binds to members of the Gαi and Gαq families,38 and RGS10 is a selective activator of Gαi activity.40 To date, only a handful of reports have described the regulation of RGS proteins by phosphorylation.41-46 This phosphorylation has been shown to modulate RGS GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity. However, to our knowledge this is the first report that RGS18 is posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation. Further work is required to establish the significance of this in the context of platelet activation.

We also report for the first time the presence of the adapter Dok-2 in platelets and demonstrate its participation in the signaling events that follow PAR-1 activation. Dok-2 is the first member of the Dok or IRS family of proteins to be found in platelets. Dok-2 has pleckstrin homology (PH) and phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domains and several other features consistent with its role as an adapter including the presence of 13 potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites and 6 PXXP motifs.23 Dok-2 acts downstream of tyrosine kinases in other cells and has been shown to participate in cell adhesion and spreading.47,48 Dok-2 has also been reported to bind c-Abl, regulating Abl kinase activity and mediating cytoskeletal reorganization,49 and to associate with rasGAP inhibiting the MAP kinase pathway.23

Although the role of Dok-2 in platelets is unknown, it is of particular interest that a recent study demonstrated the ability of Dok-1 to bind to the first of the 2 NPXY motifs in the tail of the β-3 integrin with an affinity in the range of other PTB domain-ligand interactions.50 The significance of this is underscored by our observation that outside-in signaling through the integrin αIIbβ3 promotes a marked increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Dok-2 in human and murine platelets, which is much greater in magnitude than that induced by thrombin receptors or the collagen receptor, GPVI, which signals through sequential activation of Src and Syk family kinases. Outside-in signaling through αIIbβ3 therefore appears to be the major regulatory pathway of Dok-2 tyrosine phosphorylation in platelets. This is of special interest in the context that a “knock-in” mutation in the β3 locus in the mouse genome, in which the conserved tyrosines in the 2 NPXY motifs were converted to phenylalanine residues, leads to a reduction in clot retraction and a tendency to rebleed.51 We speculate that tyrosine phosphorylation of Dok-2 mediated by αIIbβ3 may play a critical role in stabilizing thrombus formation in vivo downstream of phosphorylation of these motifs. Experiments on Dok-2–deficient mice are required to test this.

In conclusion, we have used a new approach to analyze signaling cascades in activated platelets. This approach, based on the differential analysis of the platelet proteome, yielded the identification of several novel signaling proteins and phosphorylation events in response to PAR-1 activation. The list of proteins of interest includes the adapter Dok-2, the first member of this family to be found in platelets, and demonstration of phosphorylation of RGS18. A further understanding of the role of these proteins, and others identified in this study, will contribute to a better understanding of the thrombin receptor signaling pathway, building the basis for the identification of new drug targets and development of therapeutic agents for thrombotic diseases.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 26, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2392.

Supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC). N.Z. is a Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow of the Royal Society and Research Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford. S.P.W. holds a British Heart Foundation Chair. A.C.P. is a Wellcome Trust Prize Student.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We gratefully acknowledge the constant support given by Mr David Chittenden and Mrs Vivien Freemen (Oxford Glycobiology Institute, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford). Dr Sripadi Prabhakar would like to thank the Director of the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology, Hyderabad, and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India, for granting leave.