Abstract

Increasing evidence has shown that death signaling in T cells is regulated in a complicated way. Molecules other than death receptors can also trigger T-cell death. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) or CD162 molecules cross-linked by an anti–PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody, TAB4, can trigger a death signal in activated T cells. In contrast to classic cell death, PSGL-1–mediated T-cell death is caspase independent. It involves translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor from mitochondria to nucleus and mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Ultrastructurally, both peripheral condensation of chromatin and apoptotic body were observed in PSGL-1–mediated T-cell death. Collectively, this study demonstrates a novel role for PSGL-1 in controlling activated T-cell death and, thus, advances our understanding of immune regulation.

Introduction

Death of T cells is fundamental in proper immune responses. In central and peripheral lymphoid organs, T-cell death occurs as a regulated event to ensure self-tolerance.1-4 As the consequence of an immune response in normal conditions, most antigen-activated T cells die subsequently.5-7 Activated T-cell death plays an important role in shaping and maintaining the T-cell repertoire and in avoiding undesired immune responses. Therefore, clarification of molecular mechanisms that determine death of activated T cells becomes imperative.

According to current understanding, activated T-cell death occurs in at least 2 conditions: cytokine withdrawal and repeated antigenic stimulation.8 In the former, when there is no further antigen stimulation, both interleukin 2 (IL-2) production and IL-2 receptor expression decline, and the death because of cytokine withdrawal ensues.9,10 The latter is antigen driven and mediated through death receptors such as Fas and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor.11-13 Both conditions of activated T-cell death occur by way of activation of caspases and are strictly dependent on caspase-3.14,15 Such classic caspase-activating death pathways may culminate mitochondrial dysfunction and cytochrome c release.16

There is now increasing evidence for the existence of alternative, caspase-independent machinery of cell death in T-cell development and activation.17-23 Fas-deficient lpr mice are able to eliminate T cells.24 Additionally, by repeated antigenic stimulation, activated T-cell death in FLIP (FLICE [FADD (Fas receptor–associated death domain)–like IL-1β–converting enzyme]–inhibitory protein) transgenic mice does occur. These mice do not develop lymphoproliferative disease despite their resistance to Fas-triggered death.25 In line with these observations, several reports have shown that caspase inhibition fails to prevent cell death on some death stimuli,17,18,26 suggesting the involvement of other alternative mechanisms. However, these caspase-independent pathways may be triggered in activated T cells when subjected to some death stimuli other than death receptors.27,28 Some studies have shown that anti-CD2 plus staurosporine could render human activated T cells to death through caspase-independent machinery. It is also noted that mitochondrial mediators are released to trigger chromatin condensation and mitochondrial swelling.

On the basis of the above-mentioned evidence, other death machinery may exist in parallel to the known death signal triggered by death receptors such as Fas or TNF receptors. By coordinating the different death machinery, most of the activated T cells can, therefore, be eliminated after the peaking of an immune response. To explore the death mechanisms of activated T cells, we have generated a panel of hamster monoclonal antibodies against activated mouse T cells and screened those antibodies with death-triggering function on activated mouse T cells. One of these antibodies, named TAB4, was found to recognize P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) or CD162 and was able to elicit death of activated mouse T cells. PSGL-1 is well known for mediating leukocyte trafficking by interaction with selectins during inflammatory responses. Using this PSGL-1–specific antibody, we discovered a new mechanism of activated T-cell death and a novel role for PSGL-1 in the immune system.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 and AND transgenic mice were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal Breeding and Research Center (Taipei, Taiwan).

Antibodies and reagents

Hamster anti–mouse CD3ϵ monoclonal antibody (145-2C11) and polyclonal hamster immunoglobulin (HIg) were prepared in our laboratory. Concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma, St Louis, MO), rat anti–mouse PSGL-1 (2PH129 ), Annexin V–FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) and mouse anti–cytochrome c antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-HIg (R anti-H), and goat polyclonal anti–rat IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK, and caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), rabbit anti–poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase (PARP; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), streptavidin-β galactosidase (SA-β-gal) and R anti-H IgG–HRP (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL); goat polyclonal anti-AIF (apoptosis-inducing factor) antibody and mouse anti-nucleolin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-Porin antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit ant–goat Ig (R anti-G) and Mitotracker (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), were used in the experiments. Annexin V–biotin (BioVision, Mountain View, CA), o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG, Sigma), and P-selectin and E-selectin-human Fc fusion protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were purchased.

Generation of monoclonal antibody

Two Syrian hamsters were immunized with 2 × 107 ConA-stimulated activated mouse T cells, followed by 3 boosts of activated T cells alone. Spleen cells of the immunized hamsters were prepared and fused with mouse myeloma cells. Seventy-five of 840 growing cell clones were shown positively binding on activated T cells by using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) assay. Three clones were shown to be able to induce retardation of activated T-cell proliferation (10% of retardation of activated T-cell proliferation). The most significant one, called TAB4, was maintained well, chosen for antibody production and used in this study.

Cell preparation and culture conditions

Spleen cells (2 × 106/mL) of C57BL/6 mice were activated with 2 μg/mL ConA for 48 hours. Anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) plus anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL) was also used to stimulate spleen cells in independent experiments. Spleen cells of AND T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice were activated with 50 μg/mL pigeon cytochrome c (PCC). The activated T cells were harvested by using Accu-Paque density gradient and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) complete medium containing IL-2 (100 U/mL).

Generation of stable mouse PSGL-1 transfectant in CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected with a mouse linearized full-length PSGL-1 cDNA, which was cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1/Myc-His (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). CHO cell clones expressing PSGL-1 were maintained in growth medium (Ham F12 and 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) supplemented with G418 at 500 μg/mL and screened by flow cytometry with the anti–PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody 2PH1. One stable clone, 10A, exhibiting high levels of PSGL-1 expression, was used for experiments presented here.

Depletion experiments

Activated mouse T cells (3 × 107) were lysed in 1000 μL lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)/HCL, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2) containing protease inhibitors. For depletion, cell extract was incubated at 4°C with 20 μg antibody bound to 20 μL protein G-Sepharose. Incubations were repeated twice, and each round of incubation was for 4 hours. For negative control depletions, IgG from a nonimmune hamster or rat was used. Depleted lysates were then immunoprecipitated by TAB4 or 2PH1 overnight at 4°C as described. The lysates were subjected to electrophoresis on 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed in immunoblots with 2PH1.

Assays for cell death

Annexin-V binding/propidium iodide assay. At the indicated time, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 days after initial activation, live cells were harvested and incubated in the presence of 3 μg/mL TAB4 or control antibodies plus 1.5 μg/mL R anti-H for 6 hours at 37°C, respectively. Cell death was measured with Annexin-V staining and propidium iodide.30,31 For caspase inhibition assay, activated T cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Z-VAD-FMK or Z-DEVD-FMK in titrated concentrations (0.3-100 μM) for 1 hour at 37°C before induction of cell death.

Terminal deoxy-uridine (dUTP) nick-end labeling (TUNEL). The TUNEL staining32 was assayed with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in sodium citrate (0.1%) for 2 minutes at 4°C. After blocking with 0.3% H2O2 for 1.5 hours, cells were incubated with TUNEL reagent for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then immunostained with peroxidase-conjugated antifluorescein antibody for 30 minutes at 37°C. The reaction product was demonstrated by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma). Photographs were taken with an Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

DNA electrophoresis. For measurement of oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation,33,34 the TAB4- or control antibody–treated activated T cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in a buffer (25 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 250 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 8 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 0.67 mg/mL proteinase K) for 1 hour at 55°C. The DNA was extracted, precipitated, and analyzed by 1.8% agarose electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. For pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE),35-38 cells were washed with PBS and harvested in PBS to a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/mL. Cells were embedded in agarose by adding an equal volume of liquefied 1% low-melting agarose solution to the cell suspension. The mixture was divided into aliquots into gel plug molds. DNA was digested twice with proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL; 50°C; 3 hours and 12 hours, respectively) in L buffer (100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.6, 20 mM NaCl, 1% sodium lauroyl sarcosine) and washed with 1 × TE buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.6). The gel was placed in a Clamped Homogeneous Electric Field (CHEF)–pulsed Field Electrophoresis System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) filled with 0.5 × TBE (Tris Borate EDTA) and allowed to equilibrate to 14°C for 15 hours at 6.0 V/cm with a linear switch interval ramp from 2.16 to 44.69 seconds. Molecular weight standards with size range from 48.5 to 291.0 kb (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) were used. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed by using UV transillumination by Digital Image System IS1000 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Immobilized P-selectin– and E-selectin–induced activated T-cell death. A 96-well plate (NUNC, Naperville, IL) was coated with 50 μL anti–human Fc Ig at 20 μg/mL in 1 × PBS overnight at 4°C, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 hours at 37°C and then incubated with 50 μL P- or E-selectin–human Fc fusion protein from 0.57 to 10 μg/mL for 2 hours at room temperature. In all experimental steps mentioned, each well was thoroughly washed 5 times with 1 × PBS. Then 2 × 105 activated mouse T cells at late stages were added into each well under shear (80 rpm) for 30 minutes,39-44 followed by static incubation at 37°C for a total of 5 hours. The plate was then centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was incubated with Annexin V–biotin conjugate at room temperature for 15 minutes and subsequently with SA-β-gal at 1:5000 dilution for another 30 minutes at 37°C. In every binding reaction, each well was washed twice with Annexin V binding buffer. The color development was achieved by incubation with 110 μL Z-buffer mixture (54μL 2-mercaptoethanol in 20 mL Z-buffer; Z buffer: 60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4) and 30 μL ONPG (0.04 g/mL) overnight at 4°C. The readings of optical density (OD) at 420 nm were recorded. Anti-Thy1.2 FITC (BD Pharmingen) was used to stain cells for checking cell numbers in all wells.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by intracellular esterase activity using 1 μM Calcein am (Molecular Probes), as described previously.45,46 The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence intensity was measured with microplate spectrofluorometer (Spectra MAX GeminiXS; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Electron microscopy

Following 6-hour treatment of TAB4 or control antibodies, the cells were rinsed with cold PBS and fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Specimens were sectioned with a Diatome diamond knife (Diatome, Biel, Switzerland) on a Reichert Ultracut E ultramicrotome (Leica, Wien, Austria). Semithin sections (1 μm) were obtained and stained with Toluidine blue, subsequently observed, and photographed by Leica light microscopy. Silver interference colored sections were collected onto 300-mesh copper grids. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Hitachi 7100 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV.

Immunofluorescence staining

At the indicated time, the TAB4- or control antibody-treated activated T cells were washed by cold PBS and transferred onto slides. They were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by 3 times of PBS washing. The cells were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature and stained with anti-AIF (4 μg /mL) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Cells were rinsed with PBS and stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated R anti-G (1:200 dilutions) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were rinsed with PBS several times and then mounted by cover slides with mounting media.

Subcellular fraction

The TAB4- or control antibody-treated activated T cells were harvested and washed with cold PBS. The cells were then resuspended in Dounce buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.6, 0.5 mM MgCl2) with protease inhibitor for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then subjected to 60 strokes in a glass Dounce homogenizer type B. Tonicity restoration buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.6, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 600 mM NaCl) was added to the homogenized cells to 150 mM NaCl final. The obtained cell lysate was centrifuged at 500g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the pellets were considered as nuclear fraction (N). The supernatant was centrifuged at 9000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the resultant pellets were considered as enriched with mitochondria (M). Finally, the supernatants were further centrifuged at 100 000g for 1 hour at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were concentrated by centricon and considered as cytosol fraction (C). N, M, and C fractions (5-50 μg) were further analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-AIF, antinucleolin, antiporin, anticytochrome c, and antiactin antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Activated mouse T-cell death triggered by TAB4 or control antibodies was compared by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. These data of immobilized selectin-triggered cell death were analyzed by General linear model with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than .01.

Results

TAB4 recognizes mouse PSGL-1 and triggers cell death of activated mouse T cells

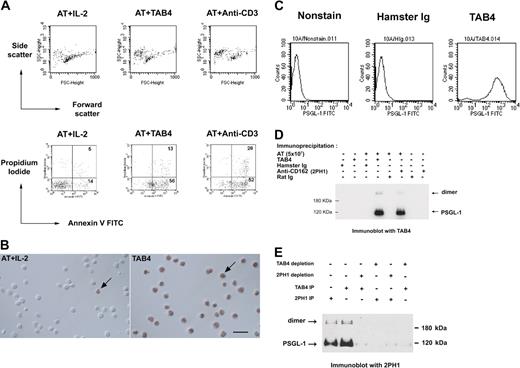

The monoclonal antibody, TAB4, against activated mouse T cells, was generated, and its death-triggering function was measured by the staining pattern of the T cells with Annexin-V and propidium iodide (Figure 1A). TAB4-mediated cell death was also confirmed by TUNEL assay (Figure 1B). These data indicate TAB4 treatment caused phosphatidylserine externalization over the cell membrane as measured by Annexin-V binding, as well as DNA strand breaks as shown by TUNEL assay. TAB4 stained CHO/PSGL-1 cells at high levels but did not stain untransfected CHO cells (Figure 1C). TAB4 reacted to 2 molecules of size 120 kDa and 240 kDa under reducing condition, which were also recognized by 2PH1,29 an anti–PSGL-1 antibody (Figure 1D). To further confirm the specificity of TAB4, the PSGL-1 protein was precleaned from the cell extracts of activated mouse T cells by TAB4 or another commercial anti–PSGL-1 antibody, 2PH1, and followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 1E, immunoblots of the residual proteins of the depleted extracts revealed that TAB4 reacted with bands of approximately 120 and 240 kDa of PSGL-1 in lysate from activated mouse T cells. Thus, the death-inducing antibody, TAB4, recognized PSGL-1.

TAB4 triggers cell death of activated mouse T cells and recognizes mouse PSGL-1. (A) Activated mouse T cells on day 5 from stimulation with ConA (2 μg/mL) were incubated with TAB4 or control antibodies plus R anti-H overnight. Following double staining with Annexin-V FITC and propidium iodide, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of dead cells. Without gating, 10% of 10 000 total events were displayed. (B) TUNEL assays of control cells (left) and TAB4-treated cells (right). Few TUNEL-positive cells could be found in the activated T-cell (AT) population with IL-2 treatment (left). Plenty of TUNEL-positive cells were observed in AT treated with TAB4 for 6 hours. Arrows: cell nuclei with TUNEL-positive staining. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) PSGL-1 transfectant cells, 10A, were stained with 5 μg/mL TAB4 or control antibody, hamster Ig, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Total cell extract of 5 × 107 activated mouse T cells at late activated stages were immunoprecipitated by anti–PSGL-1 antibodies, TAB4, and 2PH1, respectively, and followed by immunoblotting for TAB4. (E) Total cell extracts of 3 × 107 activated mouse T cells at late activated stages were depleted for PSGL-1 by 2 successive rounds of incubation with affinity-purified anti–PSGL-1 antibodies using TAB4 or 2PH1. Residual proteins of the depleted extracts were immunoblotted with 2PH1 under reducing conditions. The Zeiss Axioskop was equipped with a 40×/0.75 Zeiss Plan-Neofluar objective lens (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a Nikon D1× digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired with Nikon Capture 2 software and processed in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

TAB4 triggers cell death of activated mouse T cells and recognizes mouse PSGL-1. (A) Activated mouse T cells on day 5 from stimulation with ConA (2 μg/mL) were incubated with TAB4 or control antibodies plus R anti-H overnight. Following double staining with Annexin-V FITC and propidium iodide, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of dead cells. Without gating, 10% of 10 000 total events were displayed. (B) TUNEL assays of control cells (left) and TAB4-treated cells (right). Few TUNEL-positive cells could be found in the activated T-cell (AT) population with IL-2 treatment (left). Plenty of TUNEL-positive cells were observed in AT treated with TAB4 for 6 hours. Arrows: cell nuclei with TUNEL-positive staining. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) PSGL-1 transfectant cells, 10A, were stained with 5 μg/mL TAB4 or control antibody, hamster Ig, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Total cell extract of 5 × 107 activated mouse T cells at late activated stages were immunoprecipitated by anti–PSGL-1 antibodies, TAB4, and 2PH1, respectively, and followed by immunoblotting for TAB4. (E) Total cell extracts of 3 × 107 activated mouse T cells at late activated stages were depleted for PSGL-1 by 2 successive rounds of incubation with affinity-purified anti–PSGL-1 antibodies using TAB4 or 2PH1. Residual proteins of the depleted extracts were immunoblotted with 2PH1 under reducing conditions. The Zeiss Axioskop was equipped with a 40×/0.75 Zeiss Plan-Neofluar objective lens (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a Nikon D1× digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired with Nikon Capture 2 software and processed in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 induces death of mouse activated T cells

To measure the death-inducing effect of PSGL-1–specific antibody, we added TAB4 in activated T cells at different activation stages. We first activated T cells with ConA, resulting in T cells with purity more than 98%. Administration of TAB4 for 6 hours significantly induced death of ConA-activated mouse T cells, compared with either untreated control or those treated with control antibodies, R anti-H or HIg (Figure 2A-B). In this study, anti-CD3 treatment was used as a positive control of activated T-cell death because cross-linking of CD3 molecules on activated T cells induces the T-cell death.47-49 ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons showed the TAB4-treated group to be different from the negative control group with statistical significance (*P < .01) and significant increase of TAB4-treated effect with time was shown after day 4 (^ P < .01). That is, the maximum TAB4-induced death occurred around 4 to 6 days after activation. It was found that almost all T cells produced a large amount of interferon-γ but not IL-5 (data not shown). Taking the data of death kinetics and those of phenotype together, it seems that T helper 1 (Th1) cells are subjected to PSGL-1–triggered cell death. Similar TAB4-induced death kinetics was observed in activated T cells stimulated by anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 (data not shown). To investigate whether antigen-stimulated T cells are also subject to TAB4-induced death, we further activated T cells from TCR transgenic mice with specific antigen, pigeon cytochrome c. After activated T cells underwent 6-hour treatment with TAB4 (2, 4, and 6 days from activation, respectively), cell death was evaluated by staining with Annexin-V (Figure 2C). The results showed that cross-linking of PSGL-1 on antigen-stimulated T cells could render the cells dead, which was more significant in those T cells on day 4 from activation (*P < .01) and increase in TAB4-triggered cell death with time was statistically significant on day 6 (^ P < .01). To evaluate whether the cell death effect was associated with the amount of PSGL-1 expression, the activated mouse T cells at different activation stages were stained with TAB4. As shown in Figure 2D and Table 1, the expression of PSGL-1 molecules on T cells at 48 hours after stimulation has increased by 3 to 4 times of that on T cells before activation. The expression of PSGL-1 does not further increase in T cells at later activated stages. The sensitivity of activated T cells to PSGL-1–mediated death did not correlate with the amount of PSGL-1 molecular expression. In sum, these data suggest appropriate activation status of T cells may sensitize the PSGL-1–mediating death pathway of T cells.

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 induces activated mouse T-cell death. Mouse splenocytes of B6 mice stimulated with ConA (A-B) and those of AND TCR transgenic mice stimulated with specific antigen, PCC (C), were used. At the indicated time, activated mouse T cells were incubated with rabbit antihamster antibody plus TAB4 or control antibodies. After 6 hours, the cell death was assayed by flow cytometry with Annexin-V FITC and propidium iodide staining. Error bars in panels B and C indicate standard deviation. (D) PSGL-1 expression on T cells at different activation stages was detected by staining with TAB4 (coarse line) or hamster Ig (fine line), followed by antihamster FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. The data represent at least 3 independent experiments and were analyzed by ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *Difference of cell death between TAB4-treated and negative control antibody–treated groups, P < 0.01. ∧ Significant increase of TAB4-induced cell death with time, P < .01

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 induces activated mouse T-cell death. Mouse splenocytes of B6 mice stimulated with ConA (A-B) and those of AND TCR transgenic mice stimulated with specific antigen, PCC (C), were used. At the indicated time, activated mouse T cells were incubated with rabbit antihamster antibody plus TAB4 or control antibodies. After 6 hours, the cell death was assayed by flow cytometry with Annexin-V FITC and propidium iodide staining. Error bars in panels B and C indicate standard deviation. (D) PSGL-1 expression on T cells at different activation stages was detected by staining with TAB4 (coarse line) or hamster Ig (fine line), followed by antihamster FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. The data represent at least 3 independent experiments and were analyzed by ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *Difference of cell death between TAB4-treated and negative control antibody–treated groups, P < 0.01. ∧ Significant increase of TAB4-induced cell death with time, P < .01

Immobilized P-selectin and E-selectin trigger cell death of activated mouse T cells under shear conditions

Some studies have shown that PSGL-1 is a functional ligand for P-selectin and E-selectin.50-54 By interaction with selectins, T cells can migrate into the inflammatory site. In view of cell death triggered through cross-linking of PSGL-1 by TAB4, it was hypothesized that activated T-cell death triggered by PSGL-1 may occur by way of interaction with its ligands, P-selectin or E-selectin. To examine this hypothesis, activated T cells at later stages were added to a 96-well culture plate precoated with P-selectin, E-selectin, or TAB4, respectively, under 30-minute shear (80 rpm),39-44 followed by static culture for a total of 5 hours. We assayed cell death by cellular enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with biotinated annexin-V. As shown in Figure 3A, significant cell death was noted in E-selectin–coated wells (OD = 0.462 at 10 μg/mL), and the OD difference reached 0.282 and 0.285, respectively, compared with wells coated with BSA and anti–human Fc (OD = 0.18 and 0.177, respectively). Specific OD difference reached 0.184 in P-selectin–coated wells (OD = 0.397 at 10 μg/mL) as compared with BSA-coated well (OD = 0.213) (Figure 3B). Cells were also added to wells coated with anti-Thy1.2 and poly-lysine, respectively, as controls. No significant cell death was found (OD differences equal to –0.040 and –0.006 in anti-Thy1.2- and poly-lysine–coated wells, respectively). The death induced by P-selectin or E-selectin was compatible with that by TAB4 antibody (OD = 0.413). The death-triggering effect of E- or P-selectin was similar to that of TAB4, but differed from those of negative controls (P < .01). An ELISA for a stable T-cell marker, anti-Thy1.2 FITC,55 was also applied to guarantee equivalent numbers of cells in all wells (data not shown). ANOVA test was used to confirm the equivalence (supported by no statistical significance, P ≥ .49). In addition, the findings were confirmed by another independent approach of live cell reduction (Figure 3C).45,46 Together, these results indicate that PSGL-1–mediated activated T-cell death occurs through interaction with solid-phase P-selectin or E-selectin as well as under TAB4 treatment.

Immobilized P- or E-selectin triggers activated mouse T-cell death. ConA-stimulated activated mouse T cells were added to a 96-well plate precoated with (A) E-selectin or (B) P-selectin in titrated concentrations. After shear (80 rpm) for 30 minutes, the cells were incubated for a total of 5 hours. The cell death was assayed by cellular ELISA with biotinated Annexin, followed by streptavidin-β-gal. Color development by substrate ONPG was read at OD 420 nm. OD difference was shown as compared with BSA-coated wells. (C) Cell viability was assayed by fluorescence of Calcein am and analyzed by fluorescence microplate reader systems (excitation at 494 nm; emission at 530 nm). After incubation for 16 hours, the fluorescence of activated T cells in BSA-coated wells displayed at 756.4 and relative reduction in fluorescence of viable cells in wells coated with P- or E-selectins (5 μg/mL) compared with those in BSA-coated wells was shown. These data represent at least 3 independent experiments and were analyzed by general linear model with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Immobilized P- or E-selectin triggers activated mouse T-cell death. ConA-stimulated activated mouse T cells were added to a 96-well plate precoated with (A) E-selectin or (B) P-selectin in titrated concentrations. After shear (80 rpm) for 30 minutes, the cells were incubated for a total of 5 hours. The cell death was assayed by cellular ELISA with biotinated Annexin, followed by streptavidin-β-gal. Color development by substrate ONPG was read at OD 420 nm. OD difference was shown as compared with BSA-coated wells. (C) Cell viability was assayed by fluorescence of Calcein am and analyzed by fluorescence microplate reader systems (excitation at 494 nm; emission at 530 nm). After incubation for 16 hours, the fluorescence of activated T cells in BSA-coated wells displayed at 756.4 and relative reduction in fluorescence of viable cells in wells coated with P- or E-selectins (5 μg/mL) compared with those in BSA-coated wells was shown. These data represent at least 3 independent experiments and were analyzed by general linear model with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

PSGL-1–mediated cell death is caspase-independent

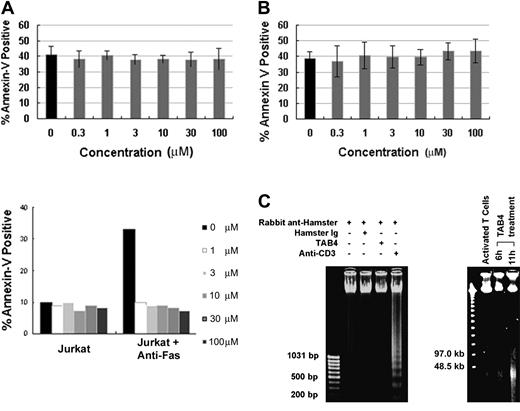

When death receptors such as Fas are ligated, some adaptor proteins are recruited to the death domain and caspase cascade is in turn activated to mediate cell death.56,57 The essential role of caspases during cell death is well substantiated by caspase inhibitor studies.58 To determine the role of caspases in PSGL-1–mediated cell death, activated mouse T cells were treated with TAB4 in the presence or absence of Z-VAD-FMK, a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, and Z-DEVD-FMK, a caspase-3 inhibitor. Our study found that the caspase inhibitors failed to block cell death mediated by PSGL-1–specific antibody, TAB4, in activated T cells (Figure 4A (upper panel) and B), whereas Fas-mediated death of Jurkat cells could be prevented by caspase inhibitor (Figure 4A, lower panel). Caspase 3, the principal executioner of most caspase-dependent cell death, was not activated during PSGL-1–mediated death pathway, as PARP, the substrate of caspase 3, remained uncleaved after TAB4 administration (data not shown). As a biochemical correlation of the morphologic features of caspase-independent cell death, TAB4-treated activated T cells developed large-scale DNA fragmentation to approximately 50 kb (Figure 4C, right panel) yet failed to show the oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation (Figure 4C, left panel). Taken together, activated T-cell death mediated by PSGL-1 was not associated with activation of caspase cascade.

PSGL-1 mediates a caspase-independent cell death. Mouse T cells at late activation stages were incubated with TAB4 in the presence of caspase inhibitors, Z-VAD-FMK (A) or Z-DEVD-FMK (B) in titrated concentration (0.3-100 μM). Jurkat cells were treated with anti-Fas antibody (CH11) as control (A, bottom panel). Positive Annexin V binding was analyzed by flow cytometry. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (C) Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was checked in cells treated with TAB4 or control antibodies (left). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA prepared from TAB4-treated or control cells is shown (right). Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

PSGL-1 mediates a caspase-independent cell death. Mouse T cells at late activation stages were incubated with TAB4 in the presence of caspase inhibitors, Z-VAD-FMK (A) or Z-DEVD-FMK (B) in titrated concentration (0.3-100 μM). Jurkat cells were treated with anti-Fas antibody (CH11) as control (A, bottom panel). Positive Annexin V binding was analyzed by flow cytometry. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (C) Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was checked in cells treated with TAB4 or control antibodies (left). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA prepared from TAB4-treated or control cells is shown (right). Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments.

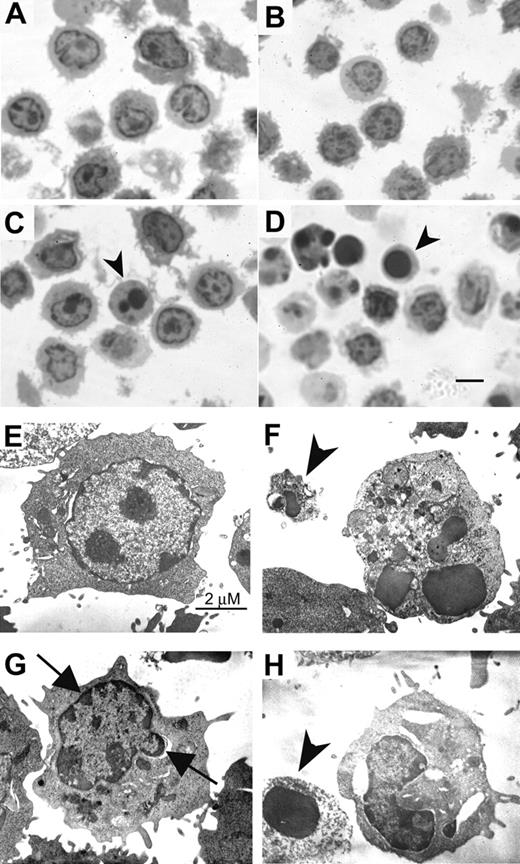

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 on activated T cells induces distinct ultrastructural changes

Recent evidence indicates a diversification of cell-death program with respect to the requirement of caspases and the alternative signaling pathways of death.59,60 The alternative signaling pathway fails to fulfill the criteria for classic apoptosis morphologically and biochemically. We next demonstrated the ultrastructural features of activated T cells following PSGL-1 cross-linking. By semithin section with Toluidine blue staining, more apoptotic bodies and cells with dark-stained nucleus were shown in TAB4-treated activated T cells than control antibody-treated cells (Figure 5A-D; for figure image acquisition information, see legend to Figure 1). The cells with dark-stained nuclei were further analyzed by electron microscopy (Figure 5E-H; Hitachi 7100 electron microscope, Tokyo, Japan). The cells treated with control antibody, HIg, showed nucleus with heterochromatin and intact cytoplasmic organelles (Figure 5E). As shown in Figure 5F, anti-CD3 antibody-treated cells displayed characteristic features of classical apoptosis, including nuclear fragmentation and apoptotic body formation. In contrast, TAB4-treated cells revealed extensive cytoplasmic vacuolization, cellular blebbing, mitochondrial swelling, and peripheral condensation of chromatin in the absence of nuclear fragmentation (Figure 5G, arrows). Membrane disruption and apoptotic body were also found (Figure 5F,H, arrowhead). Taken together, these data indicate that the death signal delivered by PSGL-1 cross-linking to the activated T cells is characterized by distinct mitochondrial and nuclear changes from classic caspase-dependent cell death.

Ultrastructural characteristics of PSGL-1–mediated cell death. Activated T cells were incubated with TAB4 or control antibodies for 6 hours. Semithin sections (1 μm) were obtained and stained with Toluidine blue (A, R anti-H; B, HIg; C, TAB4; D, anti-CD3). Cells with dark-stained nuclei were then prepared for the electronic microscopy (E, HIg; F, anti-CD3; G-H, TAB4). Arrowhead indicates apoptotic body; arrow, peripheral condensation; scale bar, 5 μm in Figure 5D.

Ultrastructural characteristics of PSGL-1–mediated cell death. Activated T cells were incubated with TAB4 or control antibodies for 6 hours. Semithin sections (1 μm) were obtained and stained with Toluidine blue (A, R anti-H; B, HIg; C, TAB4; D, anti-CD3). Cells with dark-stained nuclei were then prepared for the electronic microscopy (E, HIg; F, anti-CD3; G-H, TAB4). Arrowhead indicates apoptotic body; arrow, peripheral condensation; scale bar, 5 μm in Figure 5D.

AIF translocation occurs during the PSGL-1–mediated cell death process

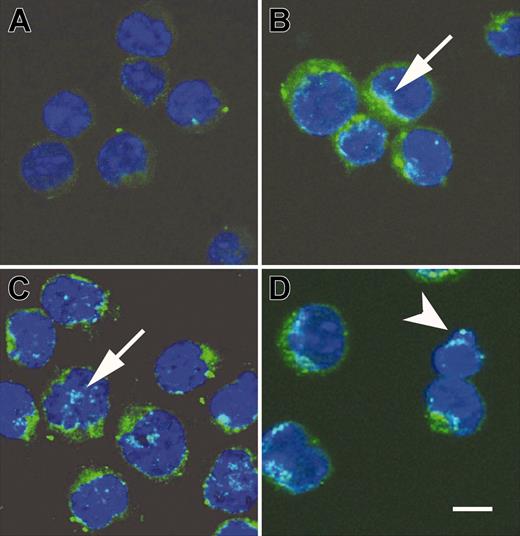

Studies have identified some apoptotic mediators and their roles in the caspase-independent death pathway.27,28,59,61-65 Translocation of the AIF from mitochondria to cytosol and nucleus may initiate nuclear condensation and subsequently mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, and the cells are doomed to death. By using confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP2 microscope [Leica, Heerbrugg, Germany] equipped with a Plan APO 63×/1.4 objective lens; images acquired with Leica multicolor analysis software for SP2), we examined whether PSGL-1–mediated cell death involved AIF translocation. It revealed punctate immunostaining pattern and perinuclear localization of AIF in untreated cells (Figure 6A). In contrast, AIF was progressively observable in a diffuse pattern and localized inside the nucleus of activated T cells treated with TAB4 for 3, 4, and 6 hours (Figure 6B-D, arrows). The amount of cells with AIF translocation was compatible with that of Annexin V positivity as shown in Figure 2B. It was correlated with concomitant digestion of chromatin into fragments of approximately 50 kb (Figure 4C, right panel). Hoechst 33342 staining revealed that nuclei were more condensed with irregular contour and occasional apoptotic body shown in activated T cells treated with TAB4 for 6 hours as shown in Figure 6D (arrowhead). A mouse T leukemia cell, RL♂1 was resistant to TAB4-induced death although with abundant expression of PSGL-1 (data not shown). The engagement of PSGL-1 could not induce significant death in activated T cells at early activation stages as shown in Figure 2B. We further checked the expression pattern and subcellular localization of AIF in RL♂1 cells and early activated T cells following TAB4 treatment. Unlike activated T cells in later stages, no significant AIF translocation was found in early-activated T cells or in RL♂1 cells (data not shown). These results indicate activated T-cell death mediated by PSGL-1 is associated with AIF translocation from mitochondria to the nucleus.

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 triggered release of AIF. AIF translocation during activated T-cell death induced by TAB4. Activated T cells were incubated with TAB4 for indicated time, 0 hours (A, untreated cells), 3 hours (B), 4 hours (C), and 6 hours (D). Following fixation, cells were stained with anti-AIF antibody and Hoechst 33342. Subcellular localization of AIF (green) and cell nuclei (blue) were visualized by a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. Arrowhead indicates apoptotic body; arrow, AIF translocation to nucleus; scale bar, 5 μm.

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 triggered release of AIF. AIF translocation during activated T-cell death induced by TAB4. Activated T cells were incubated with TAB4 for indicated time, 0 hours (A, untreated cells), 3 hours (B), 4 hours (C), and 6 hours (D). Following fixation, cells were stained with anti-AIF antibody and Hoechst 33342. Subcellular localization of AIF (green) and cell nuclei (blue) were visualized by a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. Arrowhead indicates apoptotic body; arrow, AIF translocation to nucleus; scale bar, 5 μm.

Cross-linking of PSGL-1 on activated mouse T cells initiates the release of AIF and cytochrome c from mitochondria

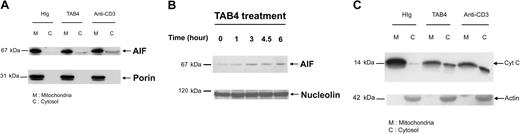

To explore whether cytochrome c release occurs in the activated T-cell death triggered by PSGL-1 cross-linking, we further performed subcellular fractionation studies. Following TAB4 treatment to activated mouse T cells at late activation stages, AIF translocation from mitochondria to cytosol (Figure 7A) and to nucleus (Figure 7B) was confirmed by Western blotting. Following a 6-hour incubation with TAB4, cytochrome c was significantly detected in cytosol (Figure 7C). Taken together, these data indicate that cross-linking of PSGL-1 initiates release of AIF and cytochrome c in activated mouse T cells at late activation stages.

Activated T-cell death triggered by PSGL-1 cross-linking involves release of mitochondrial mediators. Differential subcellular localization of mitochondrial mediators was analyzed in activated mouse T cells on death triggered by cross-linking of PSGL-1. Immunoblotting with anti-AIF antibody and anti–cytochrome c antibody, respectively, revealed that AIF translocation was first detected in the 3-hour TAB4-treated cytosolic fraction (A). Nuclear fraction of activated T cells at indicated time points following TAB4 treatment was immunoblotted by anti-AIF (B). (C) Cytochrome c release from mitochondria was detected in cytosolic fraction of 6-hour treated cells. The data represent 3 independent experiments.

Activated T-cell death triggered by PSGL-1 cross-linking involves release of mitochondrial mediators. Differential subcellular localization of mitochondrial mediators was analyzed in activated mouse T cells on death triggered by cross-linking of PSGL-1. Immunoblotting with anti-AIF antibody and anti–cytochrome c antibody, respectively, revealed that AIF translocation was first detected in the 3-hour TAB4-treated cytosolic fraction (A). Nuclear fraction of activated T cells at indicated time points following TAB4 treatment was immunoblotted by anti-AIF (B). (C) Cytochrome c release from mitochondria was detected in cytosolic fraction of 6-hour treated cells. The data represent 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

T lymphocytes are key cells in the effector arm of an immune response. T-cell death is essential for proper function of immune system and for maintaining immune homeostasis. T cells hold several death mechanisms to guarantee the elimination of undesired immune responses. Clear elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of activated T-cell death is important for depicting T-cell reactivity, immunologic memory, and autoimmunity. The present paper describes a new mechanism of activated T-cell death triggered by cross-linking of PSGL-1.

It has been well known that PSGL-1 mediates leukocyte trafficking during inflammation. But it was once reported that PSGL-1 exerts a suppressive effect on a subset of human hematopoietic progenitor cells, CD34+CD38– cells, through an unknown mechanism.66 PSGL-1 is highly expressed on naive T cells in a nonfunctional form for selectin binding. T cells obtain selectin-binding ability after cell activation.42,53,67,68 We have also observed that the binding abilities of P-selectin and E-selectin to mouse primary activated T cells have increased from day 2 and reached their peak at day 4 after activation. T cells up-regulate PSGL-1 expression within 48 hours of stimulation but become sensitive to PSGL-1–mediated cell death only at several days after activation. The kinetics of PSGL-1–triggered death of activated T cells is compatible with the selectin binding ability of PSGL-1 expressed on activated T cells. The different degrees of sensitivity to PSGL-1–mediated cell death between T cells at early and late activation stages are similar to extant findings that Fas can also selectively transduce the death signal in T cells at late activation stages independent of Fas expression amount.69,70 Accordingly, activated T-cell death mediated by PSGL-1 is activation stage dependent.

To the best of our knowledge, extravasations of T cells at sites of inflammation are initiated by capture and rolling on endothelial surface under vascular shear flow.71,72 Previous studies using blocking antibodies or gene-targeted mice have shown that selectins cooperatively regulate the leukocyte trafficking in vivo.73,74 The present study addresses, for the first time, that interaction of PSGL-1 with immobilized P- or E-selectins can induce late stage of activated T-cell death. Inflammatory cytokines can turn on the expression of P- and E-selectins on endothelial cells.75-79 Thus, one can speculate that the resistance to PSGL-1–triggering cell death may ensure naive and early activated T cells to effectively elicit a defensive immune response. Moreover, at late activation stages when the effector function was achieved, T cells in inflammatory sites are much more sensitive to death by interaction with membrane-bound P- or E-selectin or both. Thus, the local effector T cells can be prohibited from entering into circulation. Taken together, it is plausible that, because of stage dependency of PSGL-1–mediated death, the T-cell reactions can be first induced and then confined in local inflammatory sites. As a result, undesired systemic immune responses can be limited.

According to reports, functional PSGL-1 expression is the principal determinant of Th1 cells but not Th2-cell recruitment into inflamed sites of a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction of the skin as well as of inflamed intestine.80-82 Although the cell-surface expression level of PSGL-1 on Th1 and Th2 cells is similar, P-selectin can only bind to PSGL-1 on Th1 cells. It has also been demonstrated that PSGL-1 on Th1 cells interact directly with E-selectin both in vitro and in vivo.80,83 The role of PSGL-1–mediated cell death on Th1 versus Th2 immune responses remains to be investigated.

Does the interaction of selectin and PSGL-1 also influence T-cell development? Mice lacking both P- and E-selectins have normal thymus but display significant lymphocytosis and splenomegaly. PSGL-1–/– mice have normal histology of thymus, spleen, and peripheral lymph nodes by histologic analysis and show no signs of infection up to 12 months of age.84 Other independent PSGL-1–/– mice manifest moderately elevated total leukocyte counts in peripheral blood, including lymphocytes.85 Therefore, it is very likely that cross-linking of PSGL-1 may selectively act as one of the death stimuli on mature activated T cells in vivo but have little impact on developing T cells.

AIF is located in the mitochondrial intermembrane space and will translocate to the nucleus to mediate chromatin condensation in the dying neuron cells.61-64 Once AIF has entered the nucleus, it is sufficient to produce large-scale DNA fragmentation (∼ 50 kb) that cannot be inhibited by caspase inhibitors.61 The importance of AIF-triggering cell death has been emphasized by the findings of Joza et al86 that AIF deficiency causes retarded embryonic cavitation. Another recent study has shown that AIF is critical for programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans.87 In our study, AIF translocation to nucleus with a residual level of large-scale DNA fragmentation to approximately 50 kb, mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, and peripheral chromatin condensation occur during PSGL-1–mediated T-cell death, indicating a form of cell death with features distinctive from classic apoptosis of T cells. Similar patterns of cell death have been described recently in neuron studies61-64 ; it is still not yet clear how the molecular messenger emanates from PSGL-1 to AIF translocation.

Similarly, activated T-cell death initiated by AIF translocation was reported when cells were treated with anti-CD2 plus staurosporin.27,28 However, the causal relationship between the mitochondrial release of AIF and the early nuclear manifestations of cell death in activated T cells remains to be established. In our in vitro study, AIF release from mitochondria was detectable after 3 hours of anti–PSGL-1 antibody treatment. With longer treatment of anti–PSGL-1 antibody, cytochrome c release could be detected. Such sequential intracellular events are compatible with the study by Dumont et al27 that once cytochrome c has been released, the cells are fated to die.

On the basis of the findings of this study, the role of PSGL-1 in regulation of immune responses should be reconsidered more precisely. It is speculated that after an immune response peaks, a death signal may be triggered through PSGL-1 to initiate the release of apoptotic mediators such as AIF and cytochrome c from mitochondria as well as peripheral condensation of chromatin. As a consequence, activated T cells are doomed to death. Yet, it remains to be clarified how the PSGL-1 integrates with its proximal signals to render the activated T cells to die at the later stages. Nevertheless, the PSGL-1 in elimination of activated T cells found in this study may exhibit a novel function and play a parallel role with classic death pathway to guarantee a proper control of immune responses. PSGL-1 in activated T-cell death may potentially provide a better understanding of shaping and maintenance of T-cell repertoire and homeostasis. Furthermore, we also found anti–human PSGL-1 antibody capable of triggering death of phytohemagglutinin (PHA)–activated human T cells (C.-C.H. et al, unpublished data, April 2003). These properties may also render the PSGL-1 molecule an appropriate target for the treatment of autoimmune disease or graft rejection.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 15, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1679.

Supported by AbGenomics; the Confocal core facility was supported by grant 89-B-FA01-1-4 (C.-L.C.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr Alexander Y. Rudensky for helpful discussion and critical reading of this manuscript. We thank Dr Frank Oreovicz and Dr Sue-Huei Chen for English editing of the manuscript. We thank Chih-Rong Chang, Ya-Lei Wu, and Hsiao-Yu Chen for antibody preparation and Shih-Ni Wen, Hsiou-Chyi Su, and Hong-Nien Lee for technical assistance.