Abstract

Exosomes are nanovesicles released by leukocytes and epithelial cells. Although their function remains enigmatic, exosomes are a source of antigen and transfer functional major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–I/peptide complexes to dendritic cells (DCs) for CD8+ T-cell activation. Here we demonstrate that exosomes also are internalized and processed by immature DCs for presentation to CD4+ T cells. Endocytosed exosomes are sorted into the endocytic compartment of DCs for processing, followed by loading of exosome-derived peptides in MHC-II molecules for presentation to CD4+ T cells. Targeting of exosomes to DCs is mediated via milk fat globule (MFG)–E8/lactadherin, CD11a, CD54, phosphatidylserine, and the tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 on the exosome and αv/β3 integrin, and CD11a and CD54 on the DCs. Circulating exosomes are internalized by DCs and specialized phagocytes of the spleen and by hepatic Kupffer cells. Internalization of blood-borne allogeneic exosomes by splenic DCs does not affect DC maturation and is followed by loading of the exosome-derived allopeptide IEα52-68 in IAb by host CD8α+ DCs for presentation to CD4+ T cells. These data imply that exosomes present in circulation or extracellular fluids constitute an alternative source of self- or allopeptides for DCs during maintenance of peripheral tolerance or initiation of the indirect pathway of allorecognition in transplantation.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen (Ag)–presenting cells (APCs) that function as biosensors of the cellular microenvironment by detecting the presence of signals that determine T-cell tolerance or immunity.1,2 To accomplish this task, DCs acquire extracellular Ags by receptor-mediated endocytosis, macropinocytosis, or phagocytosis3-5 ; by incorporation of microvesicles shed from the surface of neighboring cells,6,7 and by their recently described interaction with nanovesicles (≤ 100 nm) termed “exosomes.”8-12 Exosomes are formed by reverse budding of the membrane of late endosomes13-15 or multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and are released to the extracellular space by fusion of MVB with the plasma membrane.13-15 Originally described in neoplastic cell lines,16 exosomes also are produced by leukocytes and epithelial cells.17-22

Although the function of exosomes still is poorly understood, exosomes are a source of Ag for APCs and participate in Ag presentation to T lymphocytes.11,12 High concentrations of exosomes expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and costimulatory molecules activate T-cell clones and T-cell lines weakly10,13 and fail to stimulate naive T cells.9,11 This impaired naive T-cell stimulatory ability of exosomes has been attributed to their low T-cell receptor–cross-linking capacity (inadequate for naive T-cell activation) and their small size and membrane composition.10 However, in the presence of DCs, exosomes increase their ability to stimulate T cells.10,11,23,24 The mechanism of interaction of extracellular exosomes with DCs is unknown. Although there is evidence that exosomes may transfer functional MHC-I/peptide complexes to DCs,24 it is unclear whether exosomes cluster or fuse with DCs or if they are internalized and processed, as occurs with vesicles derived from apoptotic cells.2-5

Herein we demonstrate that exosomes are internalized efficiently by DCs. Targeting of exosomes to DCs depends on ligands on the exosome and DC surface and is independent of complement factors. Once internalized by DCs, exosomes are sorted into recycling endosomes and then through late endosomes/lysosomes. By this mechanism, DCs process and present peptides derived from the internalized exosomes to T cells. In vivo, blood-borne exosomes are captured by DCs and specialized phagocytes of the spleen and by hepatic Kupffer cells. In the steady state, uptake of circulating exosomes by splenic DCs does not induce DC maturation and does not prevent CD40-induced DC activation in vivo. Our results demonstrate that blood-borne allogeneic exosomes are efficiently targeted, internalized, and processed by splenic DCs in vivo, a phenomenon followed by presentation of exosome-derived allopeptides by CD8α+ DCs to CD4+ T cells. Since allogeneic exosomes are a rich source of alloMHC and are targeted and processed in vivo by host DCs (without inducing their activation), intravenous administration of donor-derived exosomes may constitute a useful tool to interfere with the indirect pathway of allorecognition for induction of donor-specific transplant tolerance.

Materials and methods

Mice and reagents

C57BL/10 (B10) and BALB/c mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). 1H3.1 TCR-αβ transgenic (tg) mice were provided by Dr C. Janeway and Dr C. Viret (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mouse recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rGM-CSF) was a gift from Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ), and interleukin 4 (mrIL-4) was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). FGK4.5 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was purchased from BIO Express, West Lebanon, NH. Cytochalasin D and PKH67 were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Y-Ae mAb and 1.3H1 cells were provided by Dr C. Janeway. BEα20.6 cells were a gift of Dr P. Marrack (National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, CO). mAb 2422 was provided by Dr S. Nagata (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan).

Generation of DCs

Bone marrow (BM) DCs were generated as described.25 BM cells from femurs of B10 mice were depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis. Erythroid cells, T and B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and granulocytes were removed by incubation with mAbs (TER-119, CD3ϵ, B220, NK-1.1, Gr1, and IAb; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) followed by rabbit complement (Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada). BM cells were cultured with RPMI-1640 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 10% volume/volume fetal calf serum (FCS), glutamine, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 2-ME, and antibiotics plus mGM-CSF and mIL-4 (1000 U/mL). Splenic DCs were isolated as described.5 B10 spleens were digested with 400 U/mL collagenase (30 minutes, 37°C) and resuspended in 0.01 M EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). DC-enriched suspensions were obtained by centrifugation of spleen cells over 16% (wt/vol) metrizamide (Sigma). For splenic DC purification, DC-enriched suspensions were labeled with bead CD11c mAb and sorted with magnetic columns (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) (DC purity ≥ 92%).

Generation of BMDC-derived exosomes

BALB/c bone marrow–dendritic cells (BMDCs) were generated as described in “Generation of DCs.” On day 4, medium was replaced by fresh medium with cytokines and 10% volume/volume exosome-free FCS obtained by overnight ultracentrifugation (100 000g). DC supernatants were collected on days 6 and 8 and centrifuged at 4°C at 300g (10 minutes), 1 200g (20 minutes), 10 000g (30 minutes), and 100 000g (60 minutes).13 Exosomes were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and pelleted by overnight ultracentrifugation (100 000g). The amount of protein in the exosome preparation was assessed by Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). For flow cytometric analysis, 500 μg exosomes were incubated with a fixed number of 4.5-μm beads (Dynabeads, Dynal, Lake Success, NY) coated with CD11b or IAd mAb. Beads coated with exosomes were labeled with the following phycoerythrin (PE) mAbs (BD PharMingen): H2Dd,IAd, IE (BioDesign International, Saco, ME), CD8α, CD9, CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD16/32, CD25, CD40, CD49d, CD54, CD71, CD80, CD81, CD86, CD95, CD107a, CD178, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and anti–milk fat globule (MFG)–E8/lactadherin (clone 2422).26 Phosphatidylserine (PS) was detected with PE-annexin V (BD PharMingen).

Electron microscopy

Suspensions of exosomes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PF) and placed on grids for examination. BALB/c BMDC exosomes were labeled with 5-nm gold IAd mAb and incubated with B10 BMDCs. Then, BMDCs were fixed in PF, incubated in 3% gelatin, resuspended in 2.3 M sucrose, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin cryosections were labeled with rat anti–lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 (LAMP-1) mAb (1D4B, BD PharMingen) followed by 12-nm gold anti–rat IgGs (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). All transmission electron micrographs were obtained using JEM1210 electron microscopy (JEOL, Peabody, MA) at 80 kv. Images were printed directly from negatives (Kodak TEM Film; Kodak, Rochester, NY) and printed onto Polycontrast paper (Kodak). Images were digitalized using a ScanJet 5300C flatbed scanner (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) at 1000 dots per inch.

Internalization of exosomes by BMDCs

BALB/c BMDC exosomes were labeled with PKH67, mixed with 5 × 105 B10 BMDCs (1 hour at 37°C). Thereafter, the cells were washed with cold PBS, labeled with PE CD11c mAb, and fixed in PF. The percentage of CD11c+ DCs with PKH67+ exosomes was analyzed by flow cytometry. For blocking experiments, BMDCs were preincubated (30 minutes, 4°C) with the following mAbs (10-25 μg/mL, BD PharMingen): CD9 (KMC8), CD11a (M17/4), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), CD18 (GAME-46), CD51 (H9.2B8), CD543E2, CD612G9.G2, CD812F7, or MFG-E8 (2422).26 Some assays were performed with 10 mM O-phospho-l-serine, 10 mM O-phospho-D-serine (Sigma), 1 mg/mL H-Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Thr-Pro-OH (GRGDTP) or 1 mg/mL H-Gly-Arg-Ala-Asp-Ser-Pro-OH (GRADSP) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA).

Confocal microscopy

For identification of early and late endosomes, BMDCs were incubated with 25 μg/mL of Texas red–transferrin or 10 μg/mL Dil-low-density lipoprotein (Dil-LDL; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes at 37°C in medium without FCS and washed in PBS. BMDCs then were mixed with PKH67-labeled exosomes. The uptake of exosomes by BMDCs was stopped by washing in cold 0.1% sodium azide PBS, followed by fixation in PF. BMDCs were attached to poly-l-lysine–coated slides and imaged with a Leica TCS-NT confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Deerfield, IL).

Assay of Ag presentation

1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T lymphocytes and the T-T cell hybrids BEα20.6 and 1.3H1, all specific for the IEα52-68 (BALB/c) in IAb (B10), were used as responders.27-29 1H3.1 CD4+ T cells were purified from splenocytes of 1H3.1 mice by negative selection with CD8α, B220, IAb, NK1.1, and F4/80 mAbs followed by incubation with Dynabeads anti–rat-IgG + Dynabeads pan mouse IgG (Dynal Biotech, Norway) and magnetic sorting. The IEα52-68 peptide ASFEAQGALANIAVDKA was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and confirmed by mass spectroscopy. B10 BMDCs were pulsed with 1 μg/mL IEα52-68, the ovalbumin (OVA)–peptide SIINFEKL or graded concentrations of BALB/c exosomes. Stimulation of T-cell hybrids was performed by incubation of graded numbers of (B10) BMDCs with 105 hybrid cells per well in flat-bottom, 96-well plates. For blocking experiments, BMDCs were pretreated for 30 minutes with 30 μg/mL Y-Ae mAb or irrelevant IgG2b before adding the T cells. Twenty-four hours later, 50-μL aliquots of supernatants were collected and tested for IL-2 production on the HT-1 cell line at 5000 cells per well in 100-μL cultures in 96-well plates for 24 hours. Cells were pulsed with 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) of [3H]thymidine per well for the last 4 hours of culture. Proliferation of 1H3.1 CD4+ T cells was evaluated after 72 hours, and cells were pulsed with 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) [3H]thymidine per well for the last 16 hours of culture. The amount of radioisotope incorporated was determined using a beta counter.

Immunofluorescence

Cryostat sections (8 μm) were fixed in 4% PF, blocked with goat serum, and incubated with the following biotin-mAbs: CD11c, H2Dd (BD PharMingen), MOMA-1 (Bachem, King of Prussia, PA), F4/80 (Bachem), or ER-TR9 (Bachem). Then, slides were incubated with 1:3000 cyanine 3 (Cy3)–streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). For triple labeling, sections were incubated with biotin Y-Ae, hamster CD11c, and rat B220 mAbs. As a second step, slides were incubated with Cy3-streptavidin, Cy2 anti–hamster IgGs, and Cy5 anti–rat IgGs. Cytospins (230g) were fixed in 4% PF, blocked with goat serum, and incubated overnight (4°C) with biotin H2Dd, biotin IAb, or rat LAMP-1 mAbs followed by biotin anti–rat Igs and Cy3-streptavidin. Nuclei were stained with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole 2HCl (DAPI) (Molecular Probes).

RNAse protection assay

The analysis of cytokine mRNAs was performed by RNAse protection assay (RPA) as described.5,25 Briefly, RNA was isolated using a total RNA Isolation Kit (BD PharMingen) from CD11c+ BMDCs isolated by magnetic sorting. cDNAs encoding mouse IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p35, IL-12p40, interferon α (IFNα), IFNβ, IFNγ, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), GM-CSF, migration-inhibitory factor (MIF), and the housekeeping genes L32 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as templates for the T7 polymerase-directed synthesis of [γ-32P]-uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP)–labeled antisense RNA probes. Hybridization (16 hours at 56°C) of 5 μg each target mRNA with the antisense RNA probe sets was followed by RNAse and proteinase K treatment, phenolchloroform extraction, and ammonium acetate precipitation of protected RNA duplexes. In each RPA, the corresponding antisense RNA probe set was included as molecular weight standard. Yeast tRNA served as negative control. Samples were electrophoresed on acrylamide-urea sequencing gels. Quantification of bands was performed by densitometry (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Comparisons between means were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Student Newman Keuls test. Comparison between 2 means was performed by Student t test. A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

DCs capture extracellular exosomes: role of surface molecules

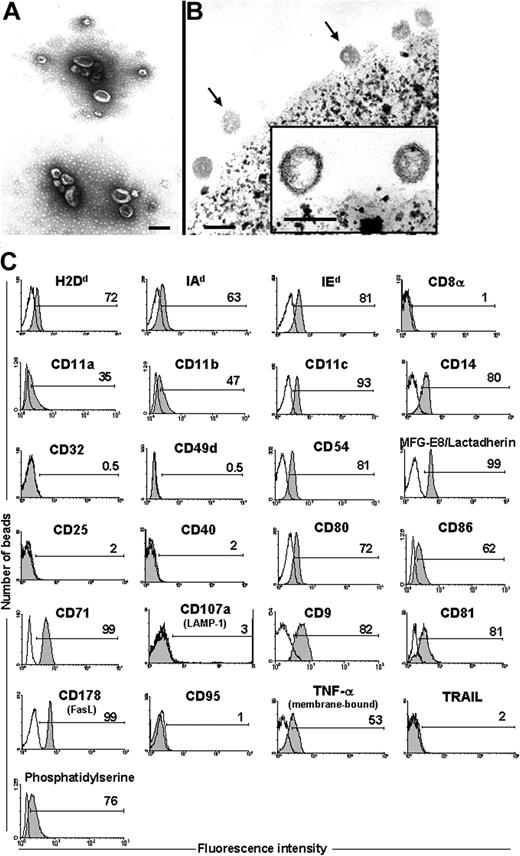

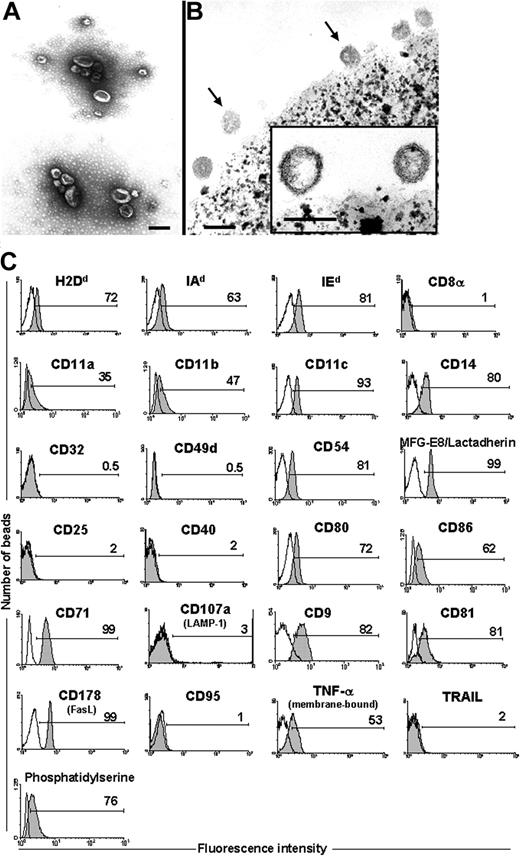

We analyzed whether murine BMDCs (B10) internalize exosomes. BALB/c BMDC exosomes consisted of 65-100 nm membrane vesicles expressing MHC-I/II, CD71 (transferrin receptor), CD80, CD86,8,21 and ligands probably involved in docking or internalization of exosomes by DCs21 [CD11a-c, CD54 (intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1; ICAM-1), milk fat globule (MFG)–E8/lactadherin, CD9, CD81, and externalized phosphatidylserine (PS) (Figure 1A-C).

Characterization of BMDC-derived exosomes. (A) Whole-mount preparations of DC exosomes show cup-shaped vesicles of 65 to100 nm diameter (×100 000; bar = 100 nm). (B) DC exosomes (arrows) attached to 4.5-μm beads used for flow cytometry. Inset: detail of exosomes (×150 000; bar = 100 nm). (C) Surface phenotype of DC exosomes by flow cytometry. DC exosomes concentrated molecules that were absent or expressed weakly on the surface of BMDCs (ie, CD14, CD178, membrane bound-TNF-α, and PS) and were negative for LAMP-1 (CD107a), a molecule confined to the limiting membrane of MVB. Open profiles indicate isotype controls. Numbers correspond to percentage of positive beads. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments.

Characterization of BMDC-derived exosomes. (A) Whole-mount preparations of DC exosomes show cup-shaped vesicles of 65 to100 nm diameter (×100 000; bar = 100 nm). (B) DC exosomes (arrows) attached to 4.5-μm beads used for flow cytometry. Inset: detail of exosomes (×150 000; bar = 100 nm). (C) Surface phenotype of DC exosomes by flow cytometry. DC exosomes concentrated molecules that were absent or expressed weakly on the surface of BMDCs (ie, CD14, CD178, membrane bound-TNF-α, and PS) and were negative for LAMP-1 (CD107a), a molecule confined to the limiting membrane of MVB. Open profiles indicate isotype controls. Numbers correspond to percentage of positive beads. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments.

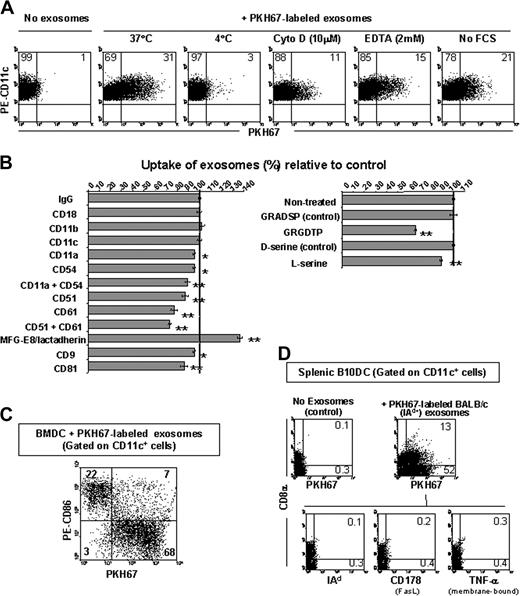

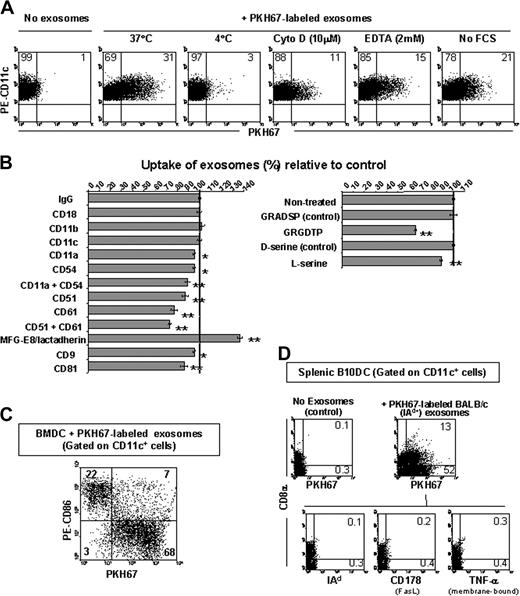

In vitro, 30% ± 7% of DCs internalized PKH67-labeled (green) exosomes within 2 hours at 37°C (Figure 2A). The uptake of exosomes decreased with cytochalasin D, EDTA, or at 4°C, suggesting that exosomes were internalized actively rather than attached to the DC surface (Figure 2A). We investigated the role of molecules expressed by the surface of exosomes and DCs in the endocytosis of exosomes. A decrease in exosome uptake by BMDCs was caused by simultaneous inhibition of αv (CD51) and β3 (CD61) integrins, CD11a and its ligand CD54, or by blockade of the tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 by mAbs (Figure 2B). The soluble analog of PS, O-phospho-l-serine, reduced the internalization of exosomes by BMDCs (P < .001), compared to the control stereoisomer O-phospho-d-serine (Figure 2B). The soluble molecule MFG-E8 has been postulated to be an opsonin that may dock exosomes to target cells.21 MFG-E8 consists of 2 factor V/VIII domains that may attach externalized PS on the exosome and 2 epidermal growth factor (EGF)–like domains with an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)–containing sequence that may bind the αvβ3/5 integrins on the DC side.21,26 The role of MFG-E8 was analyzed with the anti–mouse MFG-E8 mAb 2422, an agonistic mAb that augments endocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages.26 Similarly, mAb 2422 increased the capture of exosomes by BMDCs (Figure 2B), whereas addition of an hexapeptide containing the RGD sequence reduced the uptake of exosomes by DCs (Figure 2B), which confirms the role of molecules with RGD-domains (ie, MFG-E8) in the uptake of exosomes by DCs. No inhibition was detected following blocking of complement receptor 3 and 4 (CD11b-c/CD18) (Figure 2B). Uptake of exosomes by BMDCs was not increased by addition of (during the phagocytosis assay) or by preopsonization of exosomes with noncomplement-inactivated mouse or FCS (not shown).

Phagocytosis of exosomes by DCs. (A) Capture of DC exosomes labeled with PKH67 by BMDCs. (B) Role of surface molecules in internalization of exosomes by DCs. BMDCs were mixed with PKH67-labeled exosomes in the presence of blocking mAbs, peptides, O-phospho-D-serine (D-serine), or O-phospho-L-serine (L-serine). After incubation (1 hour, 37°C), DCs were labeled with PE CD11c mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of exosome uptake was considered only for CD11c+ cells. Uptake of PKH67+ exosomes relative to control represents the percentage of DCs with exosomes compared to their controls considered as 100% phagocytosis. Data represent 5 independent experiments. *P ≤ .01, ** P ≤ .001. (C) PKH67-labeled exosomes were internalized predominantly by immature (CD86–) BMDCs. (D) Splenic CD8α– and CD8α+ DCs (B10) capture PKH67-labeled DC exosomes (BALB/c) in vitro based on the absence of BALB/c exosome markers (IAd, FasL, and mTNF-α) on the surface of the acceptor DCs. Numbers indicate percentage of cells. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Phagocytosis of exosomes by DCs. (A) Capture of DC exosomes labeled with PKH67 by BMDCs. (B) Role of surface molecules in internalization of exosomes by DCs. BMDCs were mixed with PKH67-labeled exosomes in the presence of blocking mAbs, peptides, O-phospho-D-serine (D-serine), or O-phospho-L-serine (L-serine). After incubation (1 hour, 37°C), DCs were labeled with PE CD11c mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of exosome uptake was considered only for CD11c+ cells. Uptake of PKH67+ exosomes relative to control represents the percentage of DCs with exosomes compared to their controls considered as 100% phagocytosis. Data represent 5 independent experiments. *P ≤ .01, ** P ≤ .001. (C) PKH67-labeled exosomes were internalized predominantly by immature (CD86–) BMDCs. (D) Splenic CD8α– and CD8α+ DCs (B10) capture PKH67-labeled DC exosomes (BALB/c) in vitro based on the absence of BALB/c exosome markers (IAd, FasL, and mTNF-α) on the surface of the acceptor DCs. Numbers indicate percentage of cells. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Exosomes are internalized efficiently by immature DCs

To test if the ability to capture exosomes differed between immature (CD11c+ CD86–) and mature (CD11c+ CD86+) BM-DCs,25 BMDCs were labeled with CyChrome-CD11c and PE-CD86 mAbs after phagocytosis of PKH67-labeled exosomes. Exosomes were internalized mostly by immature (CD86–) BMDCs (Figure 2C). Next, we analyzed the ability of different splenic DC subsets to internalize exosomes. In the steady state, splenic DCs include 2 main DC populations: (1) CD11c+ CD8α– CD86– immature DCs, located in the marginal zone, and (2) CD11c+ CD8α+ CD86lo immature/semimature DCs that reside in the T-cell areas.30,31 In vitro studies showed that the PKH67-labeled exosomes (BALB/c) were internalized by CD8α– and CD8α+ splenic (B10) DCs (Figure 2D). To further confirm that exosomes were endocytosed by splenic DCs and not attached to the DC surface (as occurs in follicular DCs32 ), splenic DCs (B10) were incubated for a short time (30 minutes, 37°C) in vitro with PKH67+ exosomes (BALB/c), washed with cold EDTA/PBS, fixed, and labeled with mAbs recognizing markers present on the surface of the BALB/c exosomes (IAd, FasL, and membrane-bound TNF-α) and absent on the surface of splenic DCs (B10). The absence of exosomal (BALB/c) IAd, FasL, or TNF-α on the surface of the acceptor DCs (B10, IAb+) confirmed that exosomes were internalized and not attached to the surface of splenic DCs (Figure 2D).

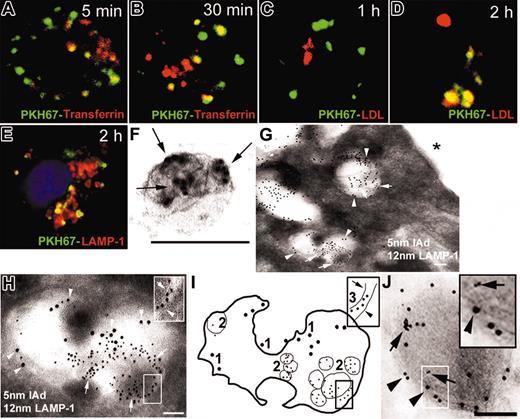

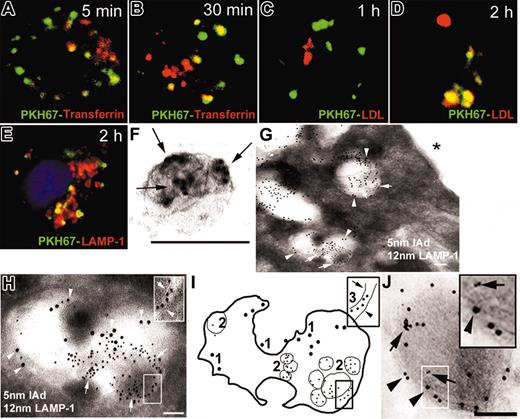

Intracellular sorting of internalized exosomes by DCs

We studied the intracellular traffic of internalized exosomes in BMDCs. Immature (CD86–) BMDCs (B10) were preincubated with Texas red–transferrin (red; to label early endosomes) or with Dil–low-density lipoprotein (Dil-LDL; red; to stain late endosomes/lysosomes) and cocultured with PKH67-labeled (green) exosomes from DCs (BALB/c) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. As early as 5 minutes, PKH67 was detected in early endosomes (Figure 3A-B) and after 2 hours, PKH67 was found in Dil-LDL+ late endosomes/lysosomes (Figure 3C-D), a result confirmed on cytospins of BMDCs labeled with lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 (LAMP-1) mAb (Figure 3E). The traffic of internalized exosomes within BMDCs was further analyzed by immunoelectron microscopy. BMDC exosomes (BALB/c) were surface labeled with 5-nm gold IAd mAb (Figure 3F) and incubated with BMDCs (B10). After 20 minutes, 5-nm gold-labeled exosomes were detected inside late endosomes expressing LAMP-1 on their limiting membrane (Figure 3G-I). At later time points (1-2 hours), 5-nm gold particles were detected in electron-dense lysosomal vesicles expressing LAMP-1 (Figure 3J). We did not find 5-nm gold-labeled exosomes or 5-nm gold particles on the surface of BMDCs (Figure 3G, asterisk).

Traffic of exosomes internalized by BMDCs. (A, B) PKH67 exosomes (green) were rapidly internalized into early endosomes labeled with Texas red–transferrin (yellow indicates colocalization of green and red). (C,D) Later, PKH67 exosomes trafficked to late endosome/lysosomes labeled by Dil-LDL (red). (E) The traffic of PKH67-labeled exosomes through late endosomes/lysosomes was confirmed by colocalization of PKH67 and LAMP-1 in cytospins of BMDCs. (F) Exosomes (BALB/c) labeled with 5-nm gold (arrows) used to study the traffic of internalized exosomes within BMDCs by electron microscopy. (G) After 20 minutes, 5-nm gold exosomes (arrows) were detected in MVB expressing LAMP-1 (12 nm gold, arrowheads). No exosomes were found attached to the DC surface (asterisk). (H) Detail of an MVB expressing LAMP-1 (12-nm gold) in the limiting membrane (arrowhead) and with internalized 5-nm gold exosomes (arrows). Insert in panel H is the membrane of an internalized 5-nm gold exosome (arrow) and the membrane of the MVB (arrowhead). (I) Diagram of panel H: (1) 12-nm gold LAMP-1 on the membrane of the MVB, (2) internalized 5-nm gold exosomes, and (3) membranes of the 5-nm gold exosome (arrows) and the MVB (arrowhead). (J) Later, 5-nm gold particles (arrows, inset) were found in lysosomes stained with 12-nm gold LAMP-1 (arrowheads). (A-D) Confocal and (E) fluorescence microscopy; nuclei were stained with DAPI. (F-J) Electron microscopy; ×100 000-150 000. Bars = 100 nm. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Traffic of exosomes internalized by BMDCs. (A, B) PKH67 exosomes (green) were rapidly internalized into early endosomes labeled with Texas red–transferrin (yellow indicates colocalization of green and red). (C,D) Later, PKH67 exosomes trafficked to late endosome/lysosomes labeled by Dil-LDL (red). (E) The traffic of PKH67-labeled exosomes through late endosomes/lysosomes was confirmed by colocalization of PKH67 and LAMP-1 in cytospins of BMDCs. (F) Exosomes (BALB/c) labeled with 5-nm gold (arrows) used to study the traffic of internalized exosomes within BMDCs by electron microscopy. (G) After 20 minutes, 5-nm gold exosomes (arrows) were detected in MVB expressing LAMP-1 (12 nm gold, arrowheads). No exosomes were found attached to the DC surface (asterisk). (H) Detail of an MVB expressing LAMP-1 (12-nm gold) in the limiting membrane (arrowhead) and with internalized 5-nm gold exosomes (arrows). Insert in panel H is the membrane of an internalized 5-nm gold exosome (arrow) and the membrane of the MVB (arrowhead). (I) Diagram of panel H: (1) 12-nm gold LAMP-1 on the membrane of the MVB, (2) internalized 5-nm gold exosomes, and (3) membranes of the 5-nm gold exosome (arrows) and the MVB (arrowhead). (J) Later, 5-nm gold particles (arrows, inset) were found in lysosomes stained with 12-nm gold LAMP-1 (arrowheads). (A-D) Confocal and (E) fluorescence microscopy; nuclei were stained with DAPI. (F-J) Electron microscopy; ×100 000-150 000. Bars = 100 nm. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

DCs process alloAgs derived from internalized exosomes for presentation to CD4+ T cells

We investigated the ability of BMDCs to process and load exosomal allopeptides into MHC class II. After 24 hours of incubation of BMDCs (B10; IAb; IE–) with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c, IAd; IEα+), mature (CD86+) BMDCs expressed IAb-IEα52-68 on the surface as assessed by staining with Y-Ae mAb, specific for IAb-IEα52-6828 (Figure 4A). To explore whether loading of the exosomal IEα52-68 allopeptide into IAb required processing of internalized exosomes via low pH vesicles, the same experiment was performed with NH4Cl, a molecule that inhibits acidification and proteolysis within endocytic vacuoles. NH4Cl decreased reversibly the formation of the Y-Ae epitope on BMDCs (B10) after ingestion of exosomes (BALB/c) (Figure 4A). Next, we determined the capacity of BMDCs (B10) to present peptides derived from exosomal Ags to T cells. After culturing with exosomes (BALB/c), BMDCs (B10) presented IAb-IEα52-68 to the specific CD4+ T-cell hybrids BEα20.6 and 1.3H1 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4B). As control, BMDCs (B10) fed with C3H exosomes that also express IEα stimulated the T-cell hybrids (Figure 4B). BMDCs (B10) pulsed with syngeneic exosomes had no effect. Stimulation of the T-cell hybrids by DCs (B10) preincubated with exosomes (BALB/c) was blocked by the Y-Ae mAb (Figure 4C).

DC process and present allopeptides derived from internalized exosomes. (A) Processing of exosomal alloAgs by BMDCs occurred within vesicles at low pH. Following culture of BMDCs (B10) with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), mature (CD86+) DCs exhibited the highest levels of IAb-IEα52-68 on the cell surface recognized by the Y-Ae mAb. NH4Cl inhibited reversibly the formation of IAb-IEα52-68 on DCs. NH4Cl did not reduce binding of IEα52-68 to IAb (not shown). Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (B) BMDCs (B10) were pulsed with graded concentrations of BALB/c exosomes or with B10 or C3H exosomes. Then, decreasing numbers of DCs were added to 105 BEα20.6 T cells specific for IAb-IEα52-68. T-cell activation was evaluated by IL-2 secretion assessed by the HT-1 cell proliferation assay. (C) Recognition of IAb-IEα52-68 by T cells was inhibited with Y-Ae mAb. IEα52-68 was used as positive control and the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL as irrelevant control. (D) BMDCs increased their capacity to present exosomal allopeptides to 1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T cells after activation via CD40. 1H3.1 T-cell proliferation was evaluated after 72 hours by [3H] TdR incorporation. Each condition was tested in triplicate and displayed as their means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

DC process and present allopeptides derived from internalized exosomes. (A) Processing of exosomal alloAgs by BMDCs occurred within vesicles at low pH. Following culture of BMDCs (B10) with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), mature (CD86+) DCs exhibited the highest levels of IAb-IEα52-68 on the cell surface recognized by the Y-Ae mAb. NH4Cl inhibited reversibly the formation of IAb-IEα52-68 on DCs. NH4Cl did not reduce binding of IEα52-68 to IAb (not shown). Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (B) BMDCs (B10) were pulsed with graded concentrations of BALB/c exosomes or with B10 or C3H exosomes. Then, decreasing numbers of DCs were added to 105 BEα20.6 T cells specific for IAb-IEα52-68. T-cell activation was evaluated by IL-2 secretion assessed by the HT-1 cell proliferation assay. (C) Recognition of IAb-IEα52-68 by T cells was inhibited with Y-Ae mAb. IEα52-68 was used as positive control and the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL as irrelevant control. (D) BMDCs increased their capacity to present exosomal allopeptides to 1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T cells after activation via CD40. 1H3.1 T-cell proliferation was evaluated after 72 hours by [3H] TdR incorporation. Each condition was tested in triplicate and displayed as their means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Next, we investigated if DC maturation enhanced the ability of BMDCs to present exosomal allopeptides to CD4+ T cells. BMDCs (B10) were treated with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) followed by stimulation with agonistic anti–CD40 IgM mAb (10 μg/mL, 16 hours) and used as stimulators of 1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T cells. 1H3.1 CD4+ T cells are specific for the IAb-IEα52-68 complex and, unlike T-cell hybrids, they resemble normal T cells in their requirements for DC costimulation.27 Activation via CD40 increased the ability of BMDCs to present exosomal allopeptides to CD4+ T cells, compared to controls (Figure 4D). Thus, DCs internalize and process allogeneic exosomes while immature and increase their capability to present exosome-derived allopeptides to CD4+ T cells following their activation.

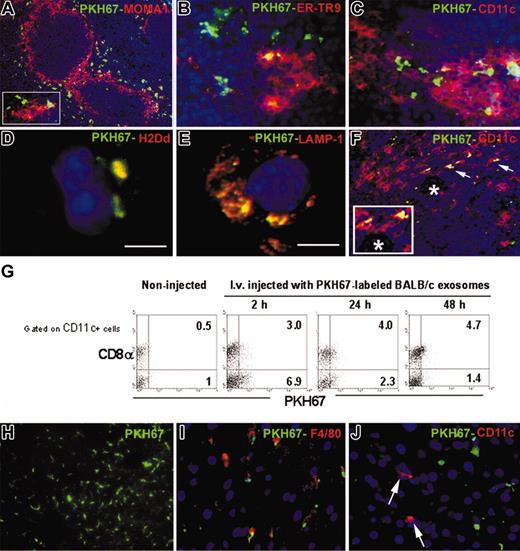

Traffic of exosomes in vivo

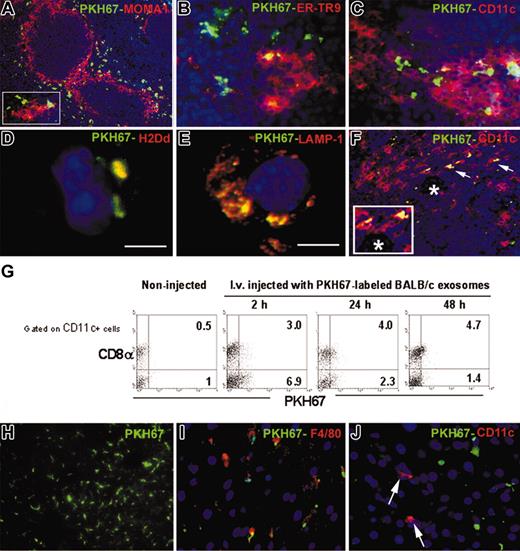

Two hours after intravenous injection of PKH67-labeled allogeneic exosomes in B10 mice, PKH67 was detected in MOMA-1+ metallophillic macrophages, ER-TR9+ macrophages, and CD11c+ DCs of the splenic marginal zone (MZ, Figure 5A-C). PKH67 colocalized with H2Dd (PKH67 and H2Dd from the BALB/c exosomes) and accumulated in LAMP-1+ vesicles of splenic B10 DCs (Figure 5D-E). After 24 to 48 hours, CD11c+ DCs with PKH67+ inclusions were found in the center of the splenic follicle (Figure 5F). The kinetics of internalization of circulating exosomes by subsets of splenic DCs was assessed by flow cytometry. Two hours after intravenous exosome administration, splenic CD11c+ DCs (most of them CD8α–) internalized circulating PKH67+ exosomes more efficiently than F4/80+ red pulp macrophages (10% ± 3% vs 3% ± 0.7%, respectively). The percentage of CD8α+ DCs with PKH67 increased at later time points (Figure 5G), an effect that may be due to CD8α up-regulation or to transfer of PKH67 to CD8α+ DCs.

Traffic of exosomes in vivo. (A) Six hours after intravenous injection, PKH67-labeled allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) were captured by MOMA-1+ macrophages (panel A, detail in insert), ER-TR9+ macrophages (B) and CD11c+ DCs (C) of the splenic MZ. (D, E) PKH67 and donor MHC-I from internalized exosomes colocalized in the cytoplasm of splenic DCs (D) and were found within LAMP-1+ vesicles (E). Scale bar equals 5 μm. (F) CD11c+ DCs (red) with PKH67+ (green) inclusions (yellow due to overlap, arrows) close to the arteriole of the splenic follicle (asterisk, inset). (G) Internalization of PKH67-labeled exosomes by subsets of splenic DCs assessed by flow cytometry at different time points. Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (H) Capture of circulating PKH67+ exosomes by the liver. (I, J) PKH67-labeled exosomes were captured by hepatic F4/80+ Kupffer cells (I) and were not detected in CD11c+ DCs (arrows). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. × 200. Panels D, E, and inserts in A and F are magnified at × 1000. Data representative of 3 independent experiments.

Traffic of exosomes in vivo. (A) Six hours after intravenous injection, PKH67-labeled allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) were captured by MOMA-1+ macrophages (panel A, detail in insert), ER-TR9+ macrophages (B) and CD11c+ DCs (C) of the splenic MZ. (D, E) PKH67 and donor MHC-I from internalized exosomes colocalized in the cytoplasm of splenic DCs (D) and were found within LAMP-1+ vesicles (E). Scale bar equals 5 μm. (F) CD11c+ DCs (red) with PKH67+ (green) inclusions (yellow due to overlap, arrows) close to the arteriole of the splenic follicle (asterisk, inset). (G) Internalization of PKH67-labeled exosomes by subsets of splenic DCs assessed by flow cytometry at different time points. Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (H) Capture of circulating PKH67+ exosomes by the liver. (I, J) PKH67-labeled exosomes were captured by hepatic F4/80+ Kupffer cells (I) and were not detected in CD11c+ DCs (arrows). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. × 200. Panels D, E, and inserts in A and F are magnified at × 1000. Data representative of 3 independent experiments.

In vivo circulating PKH67+ exosomes also were captured by hepatic (F4/80+) Kupffer cells (Figure 5H-J).

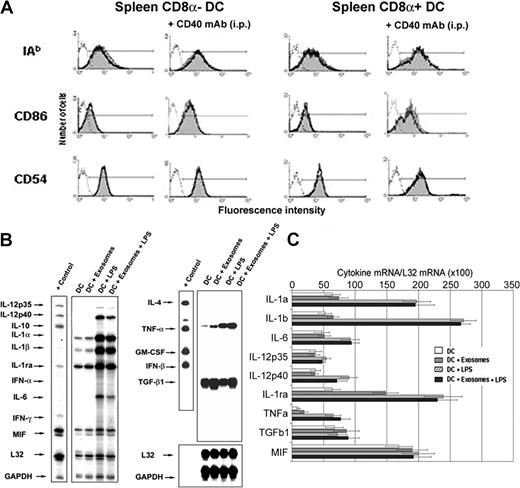

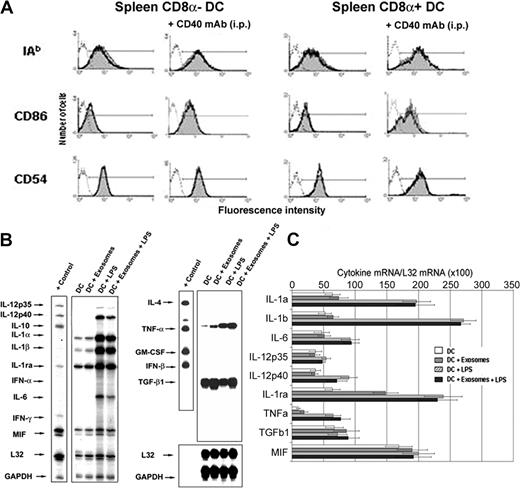

Intravenous administration of exosomes does not induce maturation of splenic DCs

We investigated if capture of blood-borne exosomes affected maturation of splenic DCs in vivo. Twenty-four hours after intravenous injection of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) into B10 mice (200 μg/mouse), splenic DCs had not up-regulated expression of the DC-maturation markers IAb, CD86, or CD54 (Figure 6A). Administration of exosomes did not interfere with splenic DC maturation induced by agonistic CD40 mAb (intraperitoneal) in vivo (FGK4.5, Figure 6A). The effect of exosomes on cytokine mRNA expression by DCs was analyzed by RPA. Due to the high number of DCs required, we used immature BMDCs (B10) selected by magnetic sorting (CD86–DCs ≥ 95%) that exhibit similar characteristics to MZ DCs5,25 and take up exosomes (Figure 2A). We did not detect significant changes in the cytokine mRNAs expressed by BMDCs (B10) 4 and 16 hours following interaction with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) (Figure 6B-C).

Uptake of exosomes does not interfere with splenic DC maturation in vivo. (A) Allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) were injected intravenously into B10 recipients, and expression of IAb, CD86, and CD54 was assessed in splenic CD8αneg and CD8α+ splenic DCs 24 hours later. Capture of circulating exosomes did not induce activation of splenic DCs and did not interfere with CD40-induced DC activation (thick line histograms) compared to splenic DCs from controls (gray histograms). White histograms represent isotype controls. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 3 animals per group. (B) Quantitative analysis of mRNA cytokine gene expression of BMDCs was performed 4 hours (not shown) and 16 hours (b) following interaction with exosomes. (C) Densitometric analysis of each lane was expressed relative to corresponding housekeeping gene transcripts (L32). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments and displayed as their means ± SD.

Uptake of exosomes does not interfere with splenic DC maturation in vivo. (A) Allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c) were injected intravenously into B10 recipients, and expression of IAb, CD86, and CD54 was assessed in splenic CD8αneg and CD8α+ splenic DCs 24 hours later. Capture of circulating exosomes did not induce activation of splenic DCs and did not interfere with CD40-induced DC activation (thick line histograms) compared to splenic DCs from controls (gray histograms). White histograms represent isotype controls. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 3 animals per group. (B) Quantitative analysis of mRNA cytokine gene expression of BMDCs was performed 4 hours (not shown) and 16 hours (b) following interaction with exosomes. (C) Densitometric analysis of each lane was expressed relative to corresponding housekeeping gene transcripts (L32). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments and displayed as their means ± SD.

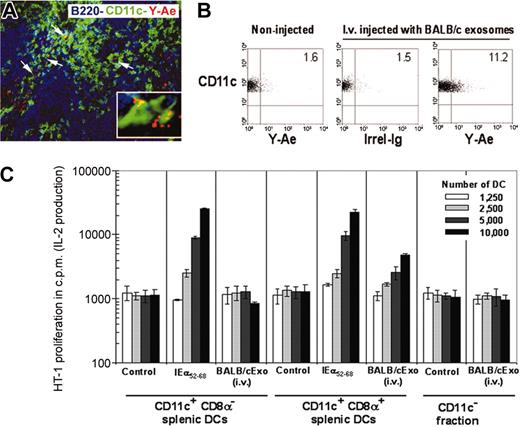

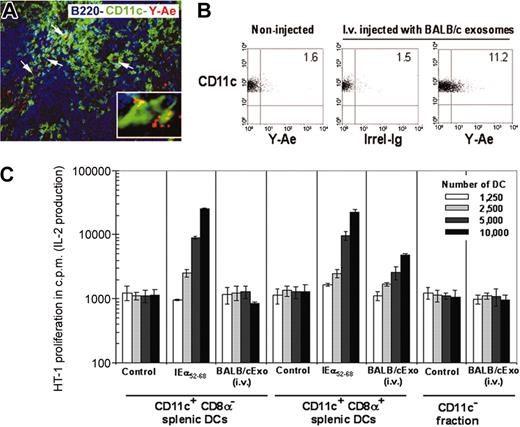

Presentation of exosomal Ags to CD4+ T cells by splenic DCs in vivo

The ability of splenic DCs to process alloAgs derived from internalized exosomes and to load exosomal allopeptides into MHC II in vivo for CD4+ T-cell presentation was analyzed. Twenty-four to 36 hours after intravenous injection of exosomes (BALB/c) into B10 mice, splenic DC expressing IAb-IEα52-68 were detected in T-cell areas of the spleen (Figure 7A). By flow cytometry, 10% to 15% of the splenic DCs loaded the exosomal allopeptide into MHC-II molecules (Figure 7B). Next, we investigated the ability of splenic DC subsets to present exosome-derived allopeptides captured from the circulation to T cells in vivo. Thirty-six hours after intravenous administration of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), splenic CD8αneg, and CD8α+ (B10) DCs were isolated by flow-sorting and used as stimulators of 1.3H1 CD4+ T cells. Only CD8α+ DCs presented IAb-IEα52-68 and induced T-cell activation (Figure 7C). CD8αneg DCs and splenic cells depleted of DCs (CD11cneg fraction) did not present the allopeptide to T cells (Figure 7C).

Presentation of exosomal allopeptides by splenic CD8α+ DCs. (A) Thirty-six hours after intravenous injection of unlabeled allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), splenic DCs (CD11c+, green) expressing IAb-IEα52-68 detected by Y-Ae mAb (red or yellow due to overlapping, arrows and inset) were detected in T-cell areas, defined by the lack of B220 staining (blue). (B) Percentage of splenic DCs (B10) with surface IAb-IEα52-68 36 hours after intravenous injection of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c). (C) Presentation of IAb-IEα52-68 to 1.3H1 T cells by different subsets of splenic DCs of B10 mice, 36 hours after intravenous administration of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments and displayed as their means ± SD.

Presentation of exosomal allopeptides by splenic CD8α+ DCs. (A) Thirty-six hours after intravenous injection of unlabeled allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), splenic DCs (CD11c+, green) expressing IAb-IEα52-68 detected by Y-Ae mAb (red or yellow due to overlapping, arrows and inset) were detected in T-cell areas, defined by the lack of B220 staining (blue). (B) Percentage of splenic DCs (B10) with surface IAb-IEα52-68 36 hours after intravenous injection of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c). (C) Presentation of IAb-IEα52-68 to 1.3H1 T cells by different subsets of splenic DCs of B10 mice, 36 hours after intravenous administration of allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments and displayed as their means ± SD.

Discussion

The immunologic role of exosomes is still unclear. T-cell exosomes expressing molecules of the TNF superfamily participate in cytotoxicity and activation-induced T-cell death.22,33 In other experimental models, exosomes have been used to promote T-cell immunity. Thus, in mice, subcutaneous administration of tumor peptide-pulsed DC exosomes induces cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) and tumor rejection,8 and subcutaneous injection of male DC exosomes into females activates CD4+ T cells specific for an H-Y peptide.11 The mechanism by which exosomes interact with DCs (or other APCs) is unknown. However, there is evidence that exosomes require the presence of DCs to activate naive T cells9,11 and that exosomes transfer functional MHC-I/peptide to acceptor DCs for presentation to CD8+ T cells.24 Thus, exosomes may potentially bind to the DC surface, fuse with the plasma membrane of DCs, or be internalized by DCs. The only known physiologic targets for exosomes are follicular DCs. B-cell–derived MHC II+ exosomes bind to the surface of follicular DCs with a possible role in development of high-affinity effector/memory B cells.32 Here, we demonstrate that exosomes are internalized by DCs through a mechanism that requires participation of the DC cytoskeleton and is calcium and temperature dependent. Our observation that the ability of BMDCs to capture exosomes decreases with cell maturation agrees with the fact that immature DCs exhibit higher endocytic capacity than mature DCs.1

There is indirect evidence that ligands present on the exosome surface are required to dock exosomes to the surface of target cells or to extracellular matrix proteins.15,34 Blocking of CD91 impairs presentation of exosomes, probably by interfering with uptake of exosomal Ags by APCs,12 and reticulocyte exosomes bind fibronectin via the α4β1 integrin.35 The soluble molecule MFG-E8/lactadherin has been postulated to be an opsonin that may dock exosomes to target cells.21,34 MFG-E8/lactadherin consists of 2 factor V/VIII domains that may attach externalized PS on the exosome surface and 2 EGF-like domains with an RGD-containing domain that bind the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins on the DC side.21,26,34 In the present study exosome uptake by DCs decreased following inhibition of the αv/β3 integrin by blockade with mAbs or by competition with RGD-containing peptides. Interestingly, we found that the agonistic anti–mouse MFG-E8 mAb 2422, reported to increase the uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages,26 also enhanced internalization of exosomes by DCs. We have shown that other surface molecules such as externalized PS, CD11a, CD54, and the tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 participate in attachment/uptake of exosomes by DCs. Although the role of tetraspanins is still unknown,36 they form complexes with integrins37 and play roles in cell adhesion.38,39 Interestingly, the blocking CD9 and CD81 mAbs used in this study impair the adherence of sperm disintegrins to the egg via dissociation of CD9 from integrins.38,39 By contrast, our results indicate that complement and iC3b receptors (CD11b/c-CD18) do not participate during capture of exosomes by DCs, as occurs during phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by DCs.5,40 This result may be explained by the fact that DC exosomes express CD55, a molecule that dissociates the catalytic subunits of C3 convertase and inhibits C3b deposition on the exosome.41

Once internalized, exosomes were sorted into the endosomal pathway by DCs. Late endosomes/MVB store MHC II and are known as MHC II–enriched compartments (MIICs),42,43 sites where Ag processing occurs. In this endosomal compartment, exosome-derived allopeptides were loaded into MHC II and transported to the DC surface for presentation to CD4+ T cells. The presence of internalized exosomes within MIICs is not surprising since the MIICs are positioned strategically in the endocytic route of DCs.43,44 MIICs are proteolytically active organelles, exhibit low pH and are the site where endocytosed proteins are processed into peptides for MHC II loading for Ag presentation.45 The fact that in this study, a pH increase reversibly impaired the capacity of DCs to present an allopeptide-derived form internalized exosomes, implies that the endocytosed vesicles must be at least partially processed within MVB. Proteins like epidermal growth factor receptor are first sorted into exosomes within late endosomes/lysosomes for proteolytic degradation.46 In a similar way, we found that internalized exosomes were processed proteolytically for Ag presentation by DCs. There is evidence that exosomes transfer peptide-MHC complexes to the surface of APCs.10,11 However, our observations and a previous report indicate that extracellular exosomes do not cluster or fuse with the plasma membrane of myeloid DCs, as occurs with follicular DCs.32 Therefore, if extracellular exosomes are targeted to late endosomes/MVB by DCs, how can peptide-MHC complexes embedded in the membrane of internalized exosomes reach the DC surface? Different groups have demonstrated recently that during the translocation of newly synthesized MHC II from late endosomes/MVB to the cell surface, endogenous exosomes bearing MHC II back fuse with the limiting membrane of MVB to mediate rapid transfer of MHC II to the cell surface via tubular vesicles.47,48 A similar mechanism may apply to internalized exosomes once they reach MVB.

Importantly, we also provide in vivo evidence that circulating exosomes are captured efficiently by DCs and specialized macrophages of the spleen and by hepatic Kupffer cells. Exosomes were internalized initially by splenic CD8αneg DCs into LAMP-1+ vesicles. Later, the lipophilic marker used to tag the exosomes was detected in DCs in the T-cell areas. These CD8α+ DCs presented self-MHC II molecules loaded with the exosomal allopeptide IEα52-68 to specific T-cell hybrids. Our results support the view that circulating exosomes are captured initially by CD8αneg DCs of the MZ that later up-regulate CD8α and mobilize to the T-cell area for Ag presentation. An alternative may be that CD8αneg DCs transfer exosomal alloAg to CD8α+ DCs resident in the T-cell area. Although the relationship between CD8αneg and CD8α+ DCs is still a matter of controversy,49-51 at least 2 independent groups have shown that CD8αneg DC differentiate into CD8α+ DCs under steadystate conditions.49,50 Since according to our results, internalization of (BMDC-derived) exosomes by splenic DCs does not affect the constitutive maturation of splenic DCs in vivo, capture of circulating exosomes should not interfere with CD8α up-regulation by DCs. Finally, a third possibility may be that CD8αneg and CD8α+ DCs exhibit different kinetics of internalization of exosomes. However, we have shown that both DC subsets capture exosomes efficiently in vitro (Figure 2D). Thus, it is probable that, unlike CD8α+ DCs of the T-cell areas, CD8αneg DCs of the MZ capture blood-borne exosomes rapidly after intravenous administration due to their proximity to the marginal sinus where exosomes circulate once they enter the spleen.

Exosomes (likely from different cellular sources) have been found in human, rodent, and fetal calf sera.34,52 The physiologic relevance of targeting circulating exosomes to splenic DCs and hepatic Kupffer cells is unknown, as is the role played by presentation of exosomal Ags by splenic CD8α+ DCs to T cells. Several observations indicate that blood-borne exosomes (derived from intestinal epithelial cells or DCs) may induce natural or acquired peripheral tolerance. Thus, in rats, intravenous injection of exosomes released by intestinal epithelium of Ag-fed animals induces Ag-specific tolerance in naive recipients,52 and intravenous administration of donor DC exosomes prolongs heart allograft survival.53 Based on our results, it is tempting to postulate that in these experimental models, immature DCs that have captured self- or allogeneic exosomes in lymphoid organs present exosome-derived Ags in a tolerogenic fashion to induce peripheral T-cell tolerance in the steady state. Importantly, we found that internalization of circulating exosomes did not induce maturation of splenic DCs. By contrast, it has been shown that subcutaneous administration of DC exosomes induces a potent immunogenic T-cell response against tumors.8 The route of exosome administration (subcutaneous vs intravenous) and the presence/absence of danger signals in the DC environment may account for the type of T-cell response induced by DCs that have internalized exosomes. In agreement with this hypothesis, we have demonstrated that the interaction of DCs with exosomes does not prevent DC maturation induced by CD40 ligation. Internalization of exosomes exerts different effects on DCs compared to phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Unlike the uptake of exosomes, ingestion of apoptotic cells prevents DC maturation and synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to CD40 ligation or lipopolysaccharide stimulation.5,40,54 This phenomenon may be ascribed to the presence of DC-deactivating molecules (such as the complement product iC3b) on the surface of apoptotic cells that are not present on the exosome surface.5,40,41 By contrast, Skokos et al12 have shown recently that mast cell exosomes activate DCs. However, unlike what seems to be constitutive secretion of exosomes by immature DCs,21 release of exosomes by mast cells is triggered by mast cell degranulation induced by danger signals.12 Different composition of exosomes released by distinct cell types or under dissimilar conditions may account for the influence of exosomes on DCs.

We have found that circulating exosome-derived alloAgs are presented to T cells by CD8α+ DCs. It is known that, in the steady state, this subset of DCs is responsible for induction of peripheral tolerance to self- and to non–self-Ags.55 Therefore, presentation of Ags derived from internalized exosomes by CD8α+ DCs in lymphoid tissues may participate in induction of peripheral T-cell tolerance in the absence of danger signals. In the transplantation setting, the uptake and processing of allogeneic exosomes by host DCs may constitute an alternative rich source of donor MHC allopeptides for the indirect pathway of allorecognition during graft rejection or induction of transplantation tolerance.56

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 29, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0824.

Supported by grants R01 075512, R21 HL69725, and R21 AI55027 (A.E.M); R01 CA100893 and R21 AI57958 (A.T.L.); R01 AI43916 and P01 CA73743 (L.D.F.); and R01 DK49745 and R01 AI41011 (A.W.T.) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The 1H3.1 TCRtg mice, the 1.3H1 T-T cell hybrid, and the mAb Y-Ae were kindly provided by the late Dr C. Janeway and Dr C. Viret (Yale University, New Haven, CT). We thank Dr Philippa Marrack (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, CO) for the BEα20.6 T-T cell hybrid. The anti–mouse MFG-E8 mAb 2422 was kindly provided by Dr S. Nagata (Osaka University, Medical School, Osaka, Japan).

![Figure 4. DC process and present allopeptides derived from internalized exosomes. (A) Processing of exosomal alloAgs by BMDCs occurred within vesicles at low pH. Following culture of BMDCs (B10) with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), mature (CD86+) DCs exhibited the highest levels of IAb-IEα52-68 on the cell surface recognized by the Y-Ae mAb. NH4Cl inhibited reversibly the formation of IAb-IEα52-68 on DCs. NH4Cl did not reduce binding of IEα52-68 to IAb (not shown). Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (B) BMDCs (B10) were pulsed with graded concentrations of BALB/c exosomes or with B10 or C3H exosomes. Then, decreasing numbers of DCs were added to 105 BEα20.6 T cells specific for IAb-IEα52-68. T-cell activation was evaluated by IL-2 secretion assessed by the HT-1 cell proliferation assay. (C) Recognition of IAb-IEα52-68 by T cells was inhibited with Y-Ae mAb. IEα52-68 was used as positive control and the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL as irrelevant control. (D) BMDCs increased their capacity to present exosomal allopeptides to 1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T cells after activation via CD40. 1H3.1 T-cell proliferation was evaluated after 72 hours by [3H] TdR incorporation. Each condition was tested in triplicate and displayed as their means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/10/10.1182_blood-2004-03-0824/6/m_zh80220469510004.jpeg?Expires=1765949344&Signature=0P3U2P39EB9Pqu89c9YTRVcV7AwgreniGQhQNvgT5qMMc432voqkinmQmm8l9qMcvfPmlrer~MEMnwyOvR3gYhKDAjWB4oIORa9eSUq5CUAjGZjNOS5YUl7O3byWCs4~jd9nBihvbYICHCVm1BoQU0icZFpnOsdl0KzRp9Vrl6PI-nfYDeDsZPvlYbQ1WHpVsvYm099Wv~dypRyQ0aAcyXPZ3lWm-s~atAppLDRpy4xe14SsqJI0b8e1X9SEEtiWFXvczk3lsoDtSVC0maAjQkZRUCAsgBmkqvXHg2-IYAyh715l8ehKrZUtij8NEGw~y7EXysDcrXRxaN6lTMVChg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. DC process and present allopeptides derived from internalized exosomes. (A) Processing of exosomal alloAgs by BMDCs occurred within vesicles at low pH. Following culture of BMDCs (B10) with allogeneic exosomes (BALB/c), mature (CD86+) DCs exhibited the highest levels of IAb-IEα52-68 on the cell surface recognized by the Y-Ae mAb. NH4Cl inhibited reversibly the formation of IAb-IEα52-68 on DCs. NH4Cl did not reduce binding of IEα52-68 to IAb (not shown). Numbers indicate percentage of cells. (B) BMDCs (B10) were pulsed with graded concentrations of BALB/c exosomes or with B10 or C3H exosomes. Then, decreasing numbers of DCs were added to 105 BEα20.6 T cells specific for IAb-IEα52-68. T-cell activation was evaluated by IL-2 secretion assessed by the HT-1 cell proliferation assay. (C) Recognition of IAb-IEα52-68 by T cells was inhibited with Y-Ae mAb. IEα52-68 was used as positive control and the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL as irrelevant control. (D) BMDCs increased their capacity to present exosomal allopeptides to 1H3.1 TCRtg CD4+ T cells after activation via CD40. 1H3.1 T-cell proliferation was evaluated after 72 hours by [3H] TdR incorporation. Each condition was tested in triplicate and displayed as their means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/10/10.1182_blood-2004-03-0824/6/m_zh80220469510004.jpeg?Expires=1765994446&Signature=G5MDRiuMcgYZBXAelMCCE1Byg7HNB5vihVgKEHCbT-W3ZJtixhSCJFrN6dfMxhiEahg-fOE9kf3fdYOrfYSkpKuWdd0dwrt44siV051TQDiDiVfkjHc-KF~YWkWdU-BV4GBYMbZmEu1OUg4EyK5QhI5dVNdd3PNqOkk9YH-fUiBPimij0kc2QRrbOhF2Zlzz94JBza4YUvpSPmHQ6FeaDYeMLecHuMvkY0rC1lb1WRuHlLv9QZBozl-juaR3-G3jIU-KfvFWB~AbmrNLTS3Phm5Dgd8cEHmnxD~91YcAREQ-jiRyXVjggeiiPjSNM-ZcF1b0Rdm-oCy1Dey6OID~aw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)