Comment on Salmi et al, page 3849

Salmi and colleagues report that CLEVER-1 is surface expressed by lymphatic and blood endothelium, and facilitates lymphocyte transmigration. Their findings will have an impact on developing new therapies for inflammation and cancer.

Lymphocytes have the unique capacity to recirculate between blood and tissues via lymphatics and secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs; lymph nodes, spleen, Peyer patches).1 This allows continuous immune surveillance and ensures rapid immune response to antigen exposure. Mechanisms that regulate lymphocyte trafficking are incompletely understood, thereby hindering development of new treatments for immune-related diseases. New insights, however, are being provided by novel studies as reported in this issue of Blood by Salmi and colleagues.

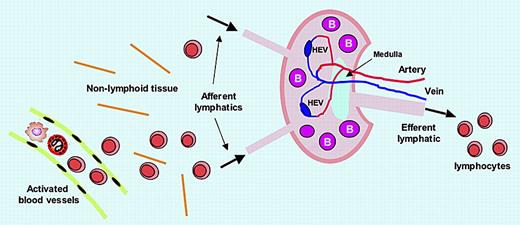

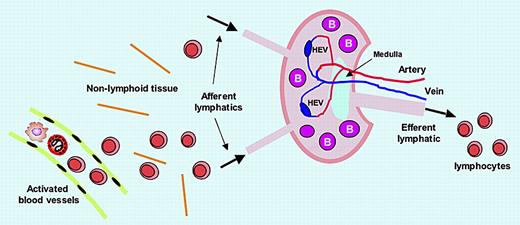

Lymphocytes encounter antigens within SLOs, which they enter via 2 routes. The majority enter SLOs by migrating out of blood vessels that traverse the SLOs, extravasating across postcapillary high endothelial venules (HEVs). The second route of entry occurs with lymphocytes that have migrated from blood microvessels into nonlymphoid tissues (eg, skin), and then enter afferent lymphatics to be carried in lymph to SLOs (see figure). In both cases, complex events result in the lymphocytes being variably retained in B- and T-cell zones in the SLO for optimizing their immune response capacity. Lymphocytes can exit the SLO only by crossing into lymphatic sinusoids and efferent lymphatics, for transport in lymph to the blood circulation via the thoracic duct.

CLEVER-1 and lymphocyte trafficking. CLEVER-1 is expressed by activated blood endothelial cells, afferent lymphatic endothelium, high endothelial venules (HEVs), sinusoid endothelium, and efferent lymphatic endothelium, supporting lymphocyte adhesion and transmigration. Thus, CLEVER-1 may have an impact on all lymphocyte trafficking steps.

CLEVER-1 and lymphocyte trafficking. CLEVER-1 is expressed by activated blood endothelial cells, afferent lymphatic endothelium, high endothelial venules (HEVs), sinusoid endothelium, and efferent lymphatic endothelium, supporting lymphocyte adhesion and transmigration. Thus, CLEVER-1 may have an impact on all lymphocyte trafficking steps.

Characterizing signals that govern lymphocyte trafficking will facilitate development of strategies to modulate the immune response to inflammation, infections, and cancer. Salmi et al have evaluated the function of the multidomain glycoprotein, common lymphatic endothelial and vascular endothelial receptor-1 (CLEVER-1). By examining tissues from patients with inflammatory skin diseases, supported by in vitro studies, they show that CLEVER-1 is surface-expressed constitutively by lymphatic endothelial cells, and, during inflammation, by blood vascular endothelial cells. CLEVER-1 supports rolling and transmigration of lymphocytes on blood vascular endothelium and mediates transmigration of leukocytes through cultured lymphatic endothelium. While other molecules contribute to lymphocyte migration across blood vessels, CLEVER-1 uniquely mediates lymphocyte adhesion and migration through lymphatics, as well as through blood vessels, but only when the latter are inflamed. Notably, CLEVER-1 is expressed on luminal and abluminal aspects of afferent lymphatic endothelium, implying that it facilitates trafficking bidirectionally. Furthermore, CLEVER-1 is located at intercellular junctions in sinusoidal cells, and thus may interact with other junctional proteins to support lymphocyte migration.2

The authors propose that CLEVER-1 is a component of a highly orchestrated mechanism, which during inflammation, is up-regulated in blood vessels to promote diapedesis of lymphocytes into nonlymphoid tissue, after which they traffick to afferent lymphatics where CLEVER-1 facilitates their abluminal-to-luminal migration for transit into SLOs (see figure). CLEVER-1 also mediates lymphocyte adhesion to efferent lymphatic endothelium,3 implying a further role in regulating egress of lymphocytes from SLOs.

These findings are of clinical interest, as CLEVER-1 blockade may selectively interfere with leukocyte extravasation into tissue from inflamed blood vascular endothelium, although simultaneously, it may also impede lymphocyte egress from SLOs. Equally intriguing is that CLEVER-1 mediates adhesion of tumor cells to vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells,4 and thus may be a target for interfering with metastasis formation.

The work of Salmi et al raises several questions: How does CLEVER-1 “know” when to help lymphocytes move from abluminal to luminal and vice-versa? What factors contribute to CLEVER-1's functional expression? Does CLEVER-1 distinguish trafficking of lymphocyte subsets? CLEVER-1 reportedly is a scavenger receptor for bacteria and advanced glycation end products. How does this function integrate into its role in lymphocyte trafficking?

While questions remain, means to regulate lymphocyte trafficking will lead to new therapies for many disabling diseases, and the findings of Salmi et al provide a solid foundation toward that end.