Abstract

The endothelial cell is a key cellular component for blood vessel formation. Many signaling receptors expressed in endothelial cells play critical roles in vascular development during embryogenesis. However, downstream response genes required for vascular differentiation are still not clearly identified. Here we describe the development of a protocol for gene-trap expression screening in embryonic stem (ES) cells for endothelial-specific genes. ES cells were differentiated into endothelial cells on an OP9 feeder cell layer in 96-well plates. In a pilot screen, 5 gene-trapped ES cell lines showed an up-regulated expression of the gene trap lacZ reporter out of 864 ES clones screened. One of the trapped genes was endoglin, an endothelial-specific transforming growth factor-β type III receptor, and another was ASPP1, a p53-binding protein. In vivo expression analysis of the lacZ reporter confirmed that both genes are specifically expressed in endothelial cells during early mouse embryogenesis. Gene-trap expression screening can thus be used to identify early endothelial-specific genes and analyze their function in mice.

Introduction

The endothelial cell is a key cellular component for blood vessel formation. During early embryogenesis, blood vessels are formed de novo as a primary capillary plexus by endothelial cell precursors derived from nascent mesodermal cells. This process is known as vasculogenesis. The capillary plexus is eventually remodeled into organized vessels, composed of endothelial cells and perivascular cells such as smooth muscle cells and pericytes.1,2 Studies on molecular mechanisms underlying vascular development during embryogenesis have revealed crucial roles for signaling receptors expressed in endothelial cells.3,4 Vascular endothelial growth factor/Flk1 signaling plays a critical role in vasculogenesis. Other signaling pathways emanating from the angiopoietin/Tie, ephrin/Eph, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and Notch receptors are important for vascular remodeling. Many of these molecules are predominantly expressed in endothelial cells at mid-gestation. However, the downstream responsive genes that are involved in elaboration of the endothelial phenotype have not yet been well defined. Devising screens to identify genes specifically expressed in early endothelial development should contribute to our knowledge on vascular development.

Gene trapping in embryonic stem (ES) cells offers a powerful tool to generate numerous insertional mutations in the mouse genome.5-8 This forward genetic strategy is based on random integration of a gene-trap vector into the mouse genome.9 A promoterless reporter gene following a splice acceptor will produce a fusion transcript between the trapped gene and the reporter gene when the vector inserts within an intron. This allows one to identify the trapped genes easily by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and also to investigate both the in vitro and in vivo expression patterns of trapped genes. Because the reporter recapitulates the expression pattern of the trapped gene, in vitro expression screening in differentiating ES cells before in vivo expression analysis is useful to identify specific reporter expression in restricted cell types such as neuronal or hematopoietic lineage cells.10-12 If the insertion of a gene-trap vector disrupts the endogenous gene structure, phenotypic analysis can be carried out in mice generated from gene-trapped ES cell lines.

Several in vitro systems have been developed for studying the differentiation of ES cells into endothelial cells. Embryoid body formation in suspension culture is a system in which endothelial tubular development is observed.13,14 A screen of embryoid body differentiation using a retroviral entrapment vector identified the vascular endothelial zinc finger protein, Vezf1.15 When embryoid bodies generated in suspension culture are attached to a substratum, endothelial cells are observed migrating out from the center of attachment.16 A previous gene-trap screen in this attached embryoid body culture identified genes that were preferentially expressed in endothelial cells.17 However, many of the genes identified by these previous screens were not specific for endothelial cells. Moreover, ES cell expansion was required before inducing ES differentiation in embryoid bodies. This is a disadvantage particularly for a large-scale, high-throughput screening. An alternative differentiation system allows endothelial cell differentiation from a small number of ES cells in coculture with OP9 feeder cell layers.18 We show here that this system can be used in a 96-well format to monitor endothelial expression of gene-trap ES cell clones. In a pilot screen of 864 ES clones, we established 2 ES cell/transgenic mouse lines conferring endothelial-specific expression of a lacZ reporter.

Materials and methods

ES cell culture

R1 ES cells19 and Flk1+/lacZ ES cells20 were maintained on a mitomycintreated embryonic fibroblast layer in ES cell medium consisting of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 1000 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 10–4 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St Louis, MO). ES cells were transferred to gelatin-coated plates a day prior to inducing differentiation. For ES cell differentiation, ES cells were cultured on the OP9 feeder cell layer21 at low cell density in ES differentiation medium consisting of alpha minimal essential medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 × 10–5 M β-mercaptoethanol in the absence of LIF. For generating embryoid bodies, ES cells were cultured for 8 days at a starting concentration of 105 cells/mL in low-attachment plates (Corning, Corning, NY) containing ES differentiation medium.

For gene trapping in ES cells, 107 R1 ES cells were electroporated with 20 μg IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector22 (kindly provided by Dr P. Gruss, Max Planck Institute of Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, Germany) linearized by ScaI. After selection for 8 days with 150 μg/mL G418, individual ES cell colonies were picked and transferred into 96-well plates containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). These cells were treated with 0.1% Trypsin/0.5 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) at 37° C for 15 minutes and split into 3 distinct 96-well plates coated with mitomycintreated embryonic fibroblast cells, 0.1% gelatin, and OP9 feeder cells, respectively. ES cells on embryonic fibroblast cells were cultured in ES cell medium and were frozen as a master stock until the results of reporter expression were obtained. ES cells on gelatin were grown in ES cell medium for 2 days and those on OP9 feeder cells were grown in ES differentiation medium for 5 days, and then stained with X-gal.

Staining of ES cells

Differentiated ES cells were stained with antibodies for Flk1 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1; Pharmingen) as described previously.23 The expression of a lacZ reporter in Flk1+/lacZ ES cells or gene-trapped ES cells were detected by X-gal staining as described previously.17

RACE

A5′ RACE was performed essentially as described previously.24 RNA was prepared from differentiated ES cells on OP9 feeder cell layer for 5 days, by using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription (Superscript II; Gibco) of 3 μg total RNA with IRES-A primer, 5′-AGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAACG-3′ (complementary to the internal ribosomal entry site [IRES] sequence of the encephalomyocarditis virus). Excess primers and deoxynucleotides were removed by using a MicroSpin S-400 column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). A polyA tail was added to the 5′ region of the cDNA by 0.6 U terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) with 0.5 mM deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP). Two consecutive polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed with 2 nested sets of primers complementary to polyA and the coding sequence of the mouse Engrailed-2 gene, respectively. The first PCR was performed through 40 cycles (94° C, 30 seconds; 55° C, 30 seconds; 72° C, 40 seconds) with NotI-(dT)18 primer (Pharmacia), and En2-A1 primer, 5′-ACTCTGGCGCCGCTGCTCTGTCAG-3′. The second PCR was performed through 40 cycles (94° C, 30 seconds; 58° C, 30 seconds; 72° C, 40 seconds) with NotI primer, 5-AACTGGAAGAATTCGCGGCCGCAGGAA-3, and En2-A2 primer, 5′-CAGGAATTCGCGGCCGCACCTGTTGGTCTGAAACTCAGCCT-3′. RACE products were subcloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced. Sequences were analyzed by comparison to the nonredundant GenBank and expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the BLASTN program (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

A3′ RACE was performed in a similar way to the 5′ RACE. (dT)18 primer was used for reverse transcription. Without a reaction of polyadenylation, 2 consecutive PCRs were performed with NotI-(dT)18 primer and Neo-S1 primer, 5′-CGCAGCGCATCGCCTTCTATCGC-3′ for the first and with NotI primer and Vec-Pax2-S1 primer, 5′-CAGGAATTCGCGGCCGCTCTAGCTAGAGCGGCCCATGGC-3′ for the second PCR, respectively.

Mice

Endoglin and ASPP1 gene-trapped ES cell lines were used to generate chimeric mice, which transmitted the alleles through the germ line. Chimeric mice were crossed with either ICR (Harland Sprague Dawley) random outbred or 129/Sv-CP inbred mice to obtain F1 heterozygous mice in a 129/Sv-ICR hybrid or 129/Sv inbred background, respectively. In vivo expression analysis of the lacZ reporter was performed only in a 129/Sv-ICR hybrid background. Embryonic day (E) 0.5 was considered to be noon of the day on which the vaginal plug was detected. Embryos from homozygous intercrosses were dissected during gestation and stained with X-gal as described previously.25

Southern blotting and genotyping

Genomic DNA was prepared from gene-trapped ES cells, digested with either XbaIor HindIII, and used for Southern blotting with a probe for β-galactosidase (β-gal) or neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) gene, respectively.

PCR analysis was used to genotype 3-week-old mice by using a piece of the ear as a DNA source. There were 3 primers used for genotyping of endoglin gene-trapped mice in a PCR reaction at annealing temperature of 67° C (Eng-GT-S, 5′-CAGGGGCTCTGGGATATGGCTG-3′; Eng-GT-A, 5′-ATGCATTACTTGGCCCACAACC-3′; and Pax2-S, 5′-CCCACCCTAGTCAAGCATCCTC-3′, where Eng-GT-A was common to both the wild-type and gene-trapped alleles). There were 3 primers used for genotyping of ASPP1 gene-trapped mice in a PCR reaction at annealing temperature of 65° C (ASPP1-GT-S, 5′-CCTTGAACAAGAGCAAGGTG-3′; ASPP1-GT-A, 5′-CACGTCACACAGCATCGGTG-3′; and PUC-A, 5′-AATCTGCTCTGATGCCGCATAG-3′, where ASPP1-GT-S was common to both the wild-type and gene-trapped alleles).

Acquisition of microscope images

Histological samples. Sections were imaged with a Leica 10× PH1 objective (NPLan, NA 0.25), 20× objective (PL FLUOTAR, NA 0.50) and 40× objective (PL FLUOTAR, NA 0.70) and photographed with KODAK elite 100ASA slide film. Subsequently, they were scanned with a Nikon Cool Pix slide scanner.

Wholemount embryos and cell culture. Whole embryos were imaged with a PLAN 1.0× objective lens with variable magnification steps on Leica Dissecting MZFLIII microscope.

Cell culture samples were imaged with Inverted Leica DMIRE microscope using 10× PH1 objective (NPLan, NA 0.25), 20× PH1 objective (NPLan, NA 0.40). Both whole-embryo and cell-culture images were obtained using an Orca Hamamatsu Digital Camera (model c4742-95) equipped with a microcolor liquid crystal filter (CRI, Boston, MA), acquired with Openlab Software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom).

All images were then constructed in Adobe Photoshop 6.0.

Results

Differentiation culture system of ES cells into endothelial cells

R1 ES cells were cultured at low cell density on the OP9 feeder cell layer in the absence of LIF after the method of Kataoka et al.18 After 3 days of culture, ES cells gave rise to colonies with Flk1+ cells at the periphery. PECAM-1/CD31,26 an endothelial cell marker, was not expressed in Flk1+ cells at day 3, but by day 5 the expression patterns of PECAM-1 and Flk1 were similar (Figure 1). PECAM-1/Flk1+ cells were easily recognized as spindle shape cells spreading out at the periphery of each colony. When we used an Flk1 heterozygous ES cell line that has a lacZ reporter inserted in the Flk1 locus,20 lacZ expression was virtually identical to Flk1 expression, as detected by immunostaining (Figure 1). A similar expression pattern of lacZ in a Tie1+/lacZ ES cell line27 was also detected at day 5 (data not shown). These results showed that 5 days of R1 ES cell culture was sufficient to promote robust endothelial differentiation on the OP9 feeder cell layer.

ES cell differentiation into endothelial cells. ES cells gave rise to colonies on the OP9 feeder cell layer in the absence of LIF. Expression of Flk1 and PECAM-1 was detected in R1 ES cells by immunostaining or in Flk1+/lacZ ES cells by X-gal staining. The expression pattern of PECAM-1 and Flk1 were similar at day 5. Scale bar, 100 μm.

ES cell differentiation into endothelial cells. ES cells gave rise to colonies on the OP9 feeder cell layer in the absence of LIF. Expression of Flk1 and PECAM-1 was detected in R1 ES cells by immunostaining or in Flk1+/lacZ ES cells by X-gal staining. The expression pattern of PECAM-1 and Flk1 were similar at day 5. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Gene trapping: in vitro endothelial expression screen

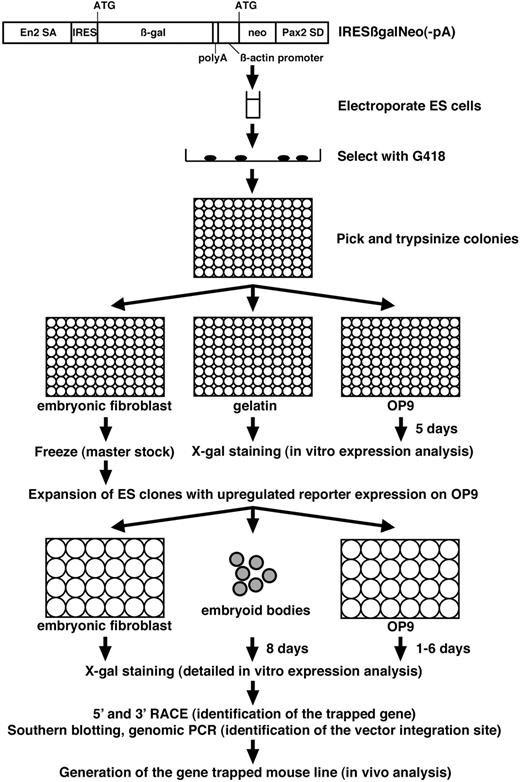

We used this culture system to screen for endothelial-specific genes by gene trapping in ES cells. The protocol of our gene-trap screen is summarized in Figure 2. We used the IRESβgalNeo(-pA) polyA trap vector.22 When this gene-trap vector integrates into genes, the ES cell lines are resistant to G418 since the neo gene is provided with a polyA signal by the 3′ downstream exons of the trapped genes. The IRESβ-gal reporter recapitulates the expression pattern of trapped genes by generating a fusion transcript with the 5′ upstream exons. A total of 864 G418-resistant ES clones were tested for lacZ expression before and after differentiation of ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 5 days in 96-well plates (Table 1). While 112 ES clones expressed lacZ both before and after differentiation, 7 ES clones showed up-regulation of lacZ expression as ES cells differentiated on the OP9 feeder cell layer (Figure 3A, data not shown). After the primary expression screening in 96-well format, the 7 ES clones that showed up-regulated lacZ expression on OP9 cells were analyzed further.

Protocol of gene-trap screen for endothelial-specific genes. IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector consists of Engrailed-2 splice acceptor (SA), IRES, β-gal, polyA signal, human β-actin promoter, neo, and Pax2 splice donor (SD).22 After electroporation of ES cells with IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector, individual G418-resistant ES cell colonies were tested for lacZ expression before and after differentiation of ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 5 days in 96-well plates. ES clones with up-regulated lacZ reporter expression on the OP9 feeder cell layer were further tested for lacZ expression on embryonic fibroblasts, in embryoid bodies, and in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 1 to 6 days. Trapped genes were identified by RACE, followed by the identification of the vector integration site. Mouse lines were generated from gene-trapped ES cells, and in vivo expression and phenotypic analysis were carried out.

Protocol of gene-trap screen for endothelial-specific genes. IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector consists of Engrailed-2 splice acceptor (SA), IRES, β-gal, polyA signal, human β-actin promoter, neo, and Pax2 splice donor (SD).22 After electroporation of ES cells with IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector, individual G418-resistant ES cell colonies were tested for lacZ expression before and after differentiation of ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 5 days in 96-well plates. ES clones with up-regulated lacZ reporter expression on the OP9 feeder cell layer were further tested for lacZ expression on embryonic fibroblasts, in embryoid bodies, and in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 1 to 6 days. Trapped genes were identified by RACE, followed by the identification of the vector integration site. Mouse lines were generated from gene-trapped ES cells, and in vivo expression and phenotypic analysis were carried out.

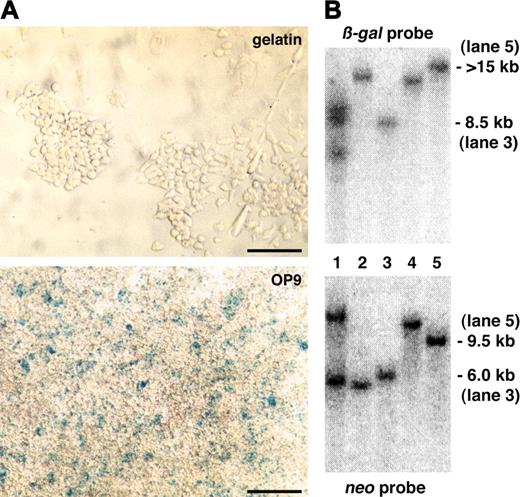

Primary expression screening and Southern blotting analysis. (A) A representative ES clone that did not show lacZ reporter expression in undifferentiated ES cells on gelatin but in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer after 5 days of culture. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Southern blotting of genomic DNA prepared from gene-trapped ES cells with a β-gal or neo probe. Approximate size of detected DNA is indicated. Trapped genes: lanes 1-2, not identified; lane 3, endoglin; lane 4, Hes1; and lane 5, ASPP1.

Primary expression screening and Southern blotting analysis. (A) A representative ES clone that did not show lacZ reporter expression in undifferentiated ES cells on gelatin but in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer after 5 days of culture. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Southern blotting of genomic DNA prepared from gene-trapped ES cells with a β-gal or neo probe. Approximate size of detected DNA is indicated. Trapped genes: lanes 1-2, not identified; lane 3, endoglin; lane 4, Hes1; and lane 5, ASPP1.

To investigate lacZ expression in more detail, we tested these 7 ES clones for lacZ expression on embryonic fibroblasts, in embryoid bodies, and in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer for 1 to 6 days. Two ES clones showed a ubiquitous expression pattern (data not shown), whereas the other 5 showed a restricted expression (Figures 4C, 5C, and data not shown). We next carried out Southern blotting of genomic DNA from these 5 gene-trapped ES cells to see if the reporter expression was based on a single integration of the gene-trap vector. One ES clone carried 2 copies of the gene-trap vector and was not analyzed further (Figure 3B).

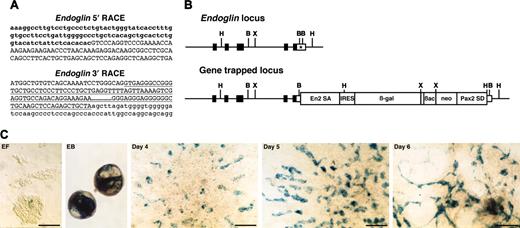

Endoglin gene-trapped clone. (A) Sequences of 5′ and 3′ RACE products. Lowercase letters represent endoglin cDNA sequence, including cording region (bold). Capital letters represent En2 splice acceptor (5′ RACE) or Pax2 splice donor sequence (3′ RACE) derived from the gene-trap vector. Underline indicates a Pax2 intronic sequence. (B) Schematic representation of genomic structure of endoglin wild-type and gene-trapped loci. Boxes represent exons, and the cording region is filled. The integration site of the gene-trap vector is indicated by an asterisk. B indicates BamHI; H, HindIII; X, XbaI. (C) In vitro expression of lacZ reporter for endoglin. EF indicates undifferentiated ES cells on embryonic fibroblast; EB, embryoid body; days 4, 5, and 6, differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Endoglin gene-trapped clone. (A) Sequences of 5′ and 3′ RACE products. Lowercase letters represent endoglin cDNA sequence, including cording region (bold). Capital letters represent En2 splice acceptor (5′ RACE) or Pax2 splice donor sequence (3′ RACE) derived from the gene-trap vector. Underline indicates a Pax2 intronic sequence. (B) Schematic representation of genomic structure of endoglin wild-type and gene-trapped loci. Boxes represent exons, and the cording region is filled. The integration site of the gene-trap vector is indicated by an asterisk. B indicates BamHI; H, HindIII; X, XbaI. (C) In vitro expression of lacZ reporter for endoglin. EF indicates undifferentiated ES cells on embryonic fibroblast; EB, embryoid body; days 4, 5, and 6, differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer. Scale bars, 50 μm.

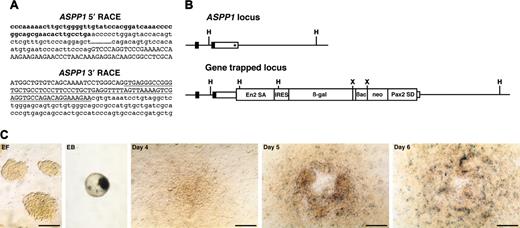

ASPP1 gene-trapped clone. (A) Sequences of 5′ and 3′ RACE products. Lowercase letters represent ASPP1 cDNA sequence including cording region (bold). Capital letters represent the En2 splice acceptor (5′ RACE) or Pax2 splice donor sequence (3′ RACE) derived from the gene-trap vector. Underline indicates a Pax2 intronic sequence. (B) Schematic representation of genomic structure of ASPP1 wild-type and gene-trapped loci. Boxes represent exons and the cording region is filled. The integration site of the gene-trap vector is indicated by an asterisk. H indicates HindIII; X, XbaI. (C) In vitro expression of lacZ reporter for ASPP1. EF indicates undifferentiated ES cells on embryonic fibroblast; EB, embryoid body; days 4, 5, and 6, differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer. Scale bars, 50 μm.

ASPP1 gene-trapped clone. (A) Sequences of 5′ and 3′ RACE products. Lowercase letters represent ASPP1 cDNA sequence including cording region (bold). Capital letters represent the En2 splice acceptor (5′ RACE) or Pax2 splice donor sequence (3′ RACE) derived from the gene-trap vector. Underline indicates a Pax2 intronic sequence. (B) Schematic representation of genomic structure of ASPP1 wild-type and gene-trapped loci. Boxes represent exons and the cording region is filled. The integration site of the gene-trap vector is indicated by an asterisk. H indicates HindIII; X, XbaI. (C) In vitro expression of lacZ reporter for ASPP1. EF indicates undifferentiated ES cells on embryonic fibroblast; EB, embryoid body; days 4, 5, and 6, differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Identification of trapped genes and integration sites of the gene-trap vector

tk;4To identify the trapped genes in the 4 gene-trap clones that showed a restricted expression, we performed 5′ and 3′ RACE. One insertion could not be identified since the RACE product produced only vector sequence (data not shown). Sequence analysis of the remaining 3 clones identified 3 genes: endoglin28 (Figure 4A), ASPP129 (Figure 5A), and Hes130 (data not shown).

The sequence of the 5′ RACE gene-trap product is generally a piece of key information to predict whether the gene-trap insertion produces a loss-of-function phenotype in mice. The 5′ RACE product for the trapped endoglin gene lacked the final exon encoding the short cytoplasmic tail (Figure 4A). However, this seemed to be a minor alternatively spliced transcript since we could not detect it by conventional reverse transcription (RT)–PCR analysis but only by nested RT-PCR (data not shown). A 5′ RACE analysis of the trapped ASPP1 gene revealed that the splicing event used a cryptic splice donor within the 3′ untranslated region (Figure 5A). These results suggested that the gene-trapped alleles for both the endoglin and the ASPP1 genes would still produce transcripts of the intact coding region. A 3′ RACE analysis showed that the RACE products contained the intronic sequence of the Pax2 splice donor of the gene-trap vector in all 3 integrations analyzed (endoglin [Figure 4A], ASPP1 [Figure 5A], and Hes1 [data not shown]). This indicates that the Pax2 splice donor did not work in these gene-trapped ES cell lines, and that G418 resistance resulted from direct readthrough to the host gene's polyA sequence. We confirmed the vector integration site in the gene-trapped loci by PCR of genomic DNA with primers specific for the vector and trapped genes. As predicted from the 3′ RACE products, we found the gene-trap vector integrated into the 3′ untranslated region of both the endoglin (Figure 4B) and ASPP1 genes (Figure 5B) with a small deletion of the flanking region. Thus, we concluded that the gene-trap insertions did not disrupt the endogenous coding region of either gene.

In vitro lacZ expression profile for endoglin and ASPP1

Detailed in vitro analysis of lacZ reporter expression revealed endoglin expression in a few ES cells on embryonic fibroblasts, with up-regulation in embryoid bodies and in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer after 4 days of culture (Figure 4C). Expression was detected in spindle shape cells spreading out at the periphery of colonies on the OP9 feeder cell layer, consistent with endothelial expression.

ASPP1 expression was not detected in ES cells cultured on embryonic fibroblasts but in embryoid bodies and in differentiated ES cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer after 4 days of culture (Figure 5C), suggesting that ASPP1 expression was localized in restricted cell types. However, because expression of the lacZ reporter gene in this gene-trapped ES cell line was very low, we could not say definitely whether it was associated specifically with spindle-shaped endothelial cells.

In vivo expression and phenotypic analysis in mice generated from gene-trapped ES cells

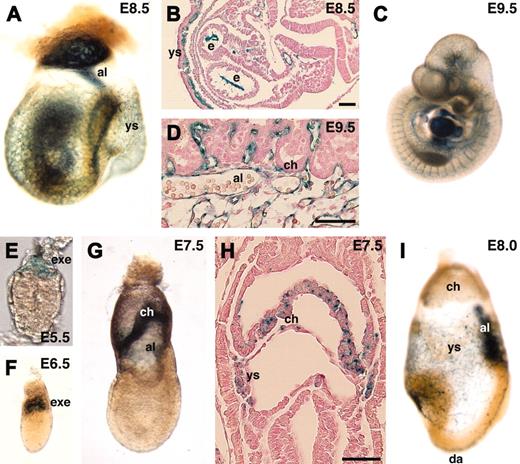

We next generated mouse lines from the gene-trapped ES cell lines and investigated in vivo expression of the lacZ reporters during early mouse embryogenesis. endoglin is a TGF-β type III receptor and is known to be strongly expressed in endothelial cells.28 As expected, endoglin was specifically detected in endothelial cells at E8.5 to E10.5 (Figure 6A-D). In addition to endothelial cells, the extraembryonic ectoderm expressed endoglin. Although a previous report showed endoglin expression at E6.5,31 we could detect it even earlier. endoglin was not detected in the blastocyst (data not shown) but in the extraembryonic ectoderm at E5.5 to E6.5 (Figure 6E-F). At E7.5, endoglin was detected in the chorionic ectoderm and mesoderm, and the yolk sac mesoderm (Figure 6G-H). The expression in the chorionic ectoderm was stronger in more proximal tissue to the embryo proper. At E8.0, expression in endothelial cells became stronger, but expression in the chorion was down-regulated (Figure 6I). Previous reports on targeted disruption of the endoglin gene in mice demonstrated that null mutant embryos die at mid-gestation.32,33 To see if the gene-trap insertion affected embryogenesis, we genotyped F2 progeny from F1 heterozygous intercrosses at 3 weeks of age. In contrast to null mutant mice, homozygous gene-trap mutant mice for the endoglin gene were viable at a normal Mendelian frequency (wild-type 21.3%, heterozygous 50.6%, and homozygous 28.1% in a 129/Sv-ICR hybrid background, n = 89; wild-type 28.0%, heterozygous 47.0%, and homozygous 25.0% in a 129/Sv inbred background, n = 132), confirming that the function of the endogenous endoglin gene was not markedly affected by the gene-trap insertion.

In vivo expression of lacZ reporter in endoglin gene-trapped embryos. (A-D,I) endoglin was specifically expressed in endothelial cells. Note that the expression was not detected in the chorion of the placenta (D) at E9.5. (E-H) endoglin expression was also detected in the extraembryonic ectoderm, chorion, and yolk sac mesoderm. al indicates allantois; ch, chorion; da, dorsal aorta; e, endocardium; exe, extraembryonic ectoderm; ys, yolk sac. Scale bars, 50 μm. Original magnifications: × 40 (A), × 25 (C), × 400 (E), and × 100 (F,G,I).

In vivo expression of lacZ reporter in endoglin gene-trapped embryos. (A-D,I) endoglin was specifically expressed in endothelial cells. Note that the expression was not detected in the chorion of the placenta (D) at E9.5. (E-H) endoglin expression was also detected in the extraembryonic ectoderm, chorion, and yolk sac mesoderm. al indicates allantois; ch, chorion; da, dorsal aorta; e, endocardium; exe, extraembryonic ectoderm; ys, yolk sac. Scale bars, 50 μm. Original magnifications: × 40 (A), × 25 (C), × 400 (E), and × 100 (F,G,I).

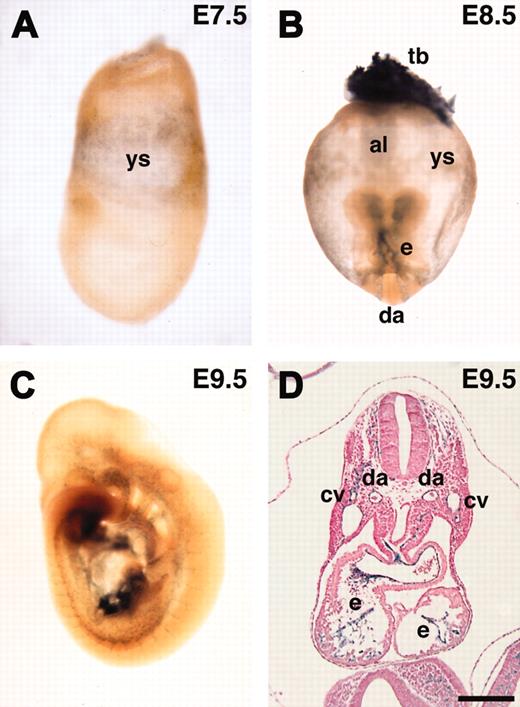

ASPP1 has been shown to be a p53-binding protein that stimulates the apoptotic function of p53 in vitro.29 However, its in vivo expression and role remain to be investigated. We investigated the expression of the lacZ reporter during early mouse embryogenesis. We could not detect ASPP1 expression at E6.5 (data not shown). ASPP1 was first detected in the yolk sac mesoderm at E7.5 and later specifically in endothelial cells at E8.5 and E9.5 (Figure 7A-D). These results confirmed that ASPP1 was an endothelial-specific gene during early mouse embryogenesis, although the lacZ expression was weak both in vivo and in vitro. X-gal staining at the later embryonic stage (E16.5) revealed that lacZ expression was also detected in neural tissues and the epithelium in the lung and intestine (not shown). Northern analysis with RNA from adult tissues showed that ASPP1 transcript was detected in the brain, lung, testis, heart, liver, and kidney (not shown). These results showed that ASPP1 is specifically expressed in endothelial cells during early embryogenesis but not at later stages and in the adult.

In vivo expression of lacZ reporter in ASPP1 gene-trapped embryos. (A-D) ASPP1 was expressed in the yolk sac mesoderm and endothelial cells. (B) ASPP1 expression was also detected in the trophoblast. al indicates allantois; cv, cardinal vein; da, dorsal aorta; e, endocardium; tb, trophoblast; ys, yolk sac. Scale bars, 200 μm. Original magnifications: × 100 (A), × 40 (B), and × 25 (C).

In vivo expression of lacZ reporter in ASPP1 gene-trapped embryos. (A-D) ASPP1 was expressed in the yolk sac mesoderm and endothelial cells. (B) ASPP1 expression was also detected in the trophoblast. al indicates allantois; cv, cardinal vein; da, dorsal aorta; e, endocardium; tb, trophoblast; ys, yolk sac. Scale bars, 200 μm. Original magnifications: × 100 (A), × 40 (B), and × 25 (C).

It is unknown whether ASPP1 is essential for embryogenesis. The 5′ RACE analysis described above suggested that the genetrap insertion would not produce a loss-of-function allele for the ASPP1 gene. When we genotyped F2 progeny from F1 heterozygous intercrosses at 3 weeks of age, we found that homozygous gene-trap mutant mice for the ASPP1 gene were viable at a normal Mendelian frequency without any obvious defect (wild-type 24.4%, heterozygous 57.7%, and homozygous 17.9% in a 129/Sv-ICR hybrid background, n = 78; wild-type 27.9%, heterozygous 47.1%, and homozygous 25.0% in a 129/Sv inbred background, n = 204).

Discussion

Here we provide proof-of-principle for a multiplexed expression screening strategy to identify gene-trap insertions in endothelial-specific genes. By using ES cell cultures on OP9 feeder cell layers in a 96-well plate format, we could screen for endothelial-specific expression at 5 days of culture. In a pilot screen of 864 clones, we identified 5 of 864 gene-trap insertions that showed up-regulated lacZ reporter expression in differentiated ES cells. There were 3 genes associated with the gene-trap insertions that were successfully cloned. One of the trapped genes was endoglin, a known endothelial-specific TGF-β type III receptor, and another was ASPP1, a p53-binding protein, whose expression has not previously been described. In vivo expression analysis confirmed that both genes are specifically expressed in endothelial cells during early mouse embryogenesis. The third gene encoded the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, Hes1, which was previously associated with neural development.

Several culture systems for ES cell differentiation into endothelial cells have previously been reported.34 However, the culture system described here is most suitable for a large-scale, high-throughput screening for endothelial-specific genes. First, only a small number of ES cells is required because even a single ES cell can survive to form a colony containing endothelial cells on the OP9 feeder cell layer. After picking G418-resistant ES clones, most cells can be retained for master stocks of ES clones while, at the same time, the expression screening is carried out in 96-well format. Second, the differentiation time is short (5 days) and passage of cells is not required during the differentiation of the ES cells. Third, this system yields easily observable endothelial cells. Although endothelial cells do not form tubular structures in this 2-dimensional culture, they are easily recognized by morphology and distribution in colonies. In addition, the ability to seed multiple plates from the same starting colonies allows comparison of gene-trap expression in undifferentiated cells and after endothelial differentiation. This comparison is essential to eliminate those integrations into genes that are highly expressed in both states. Some endothelial-specific genes such as Tie2 and PECAM-1 are weakly detected in undifferentiated ES cells.35 Expression of these genes is strongly up-regulated after differentiation of ES cells. Comparison of expression levels in undifferentiated ES cells and after endothelial differentiation allows these kinds of genes to be identified. In fact, the endoglin gene-trap line showed some expression in undifferentiated ES cells.

The 3 genes identified in the screen demonstrate that the screen is able to detect highly expressed and highly specific endothelial genes (endoglin), genes whose expression is endothelial-specificin the early embryo only (ASSP1), and genes whose endothelial expression is not apparent by normal in situ techniques (Hes1). endoglin expression is highly specific to the endothelial lineages at all stages of development, as shown by the gene-trap insertion and other expression studies. An essential role for endoglin in vascular development has been well-studied by gene-targeting studies. endoglin–/– embryos die at mid-gestation due to a cardiovascular defect.32,33 Haploinsufficiency of endoglin results in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) type 1 in humans.36 endoglin+/– mice also show signs of HHT in a 129/Ola but not C57Bl/6 background, suggesting the presence of modifier genes.33,37 A recent report demonstrated that homozygous mutant embryos for the endoglin gene exhibit arterio-venous malformations similar to those mutant for Alk1, a gene responsible for HHT type 2,38-40 implicating endoglin as an accessory coreceptor that modulates Alk1 signaling. Sorensen et al40 proposed that endoglin and Alk1 are necessary for the maintenance of arterial-venous vascular beds and that attenuation of the Alk1 signaling pathway is the precipitating event in the etiology of HHT.

Our report is the first demonstration that ASPP1 is specifically expressed in endothelial cells during early mouse embryogenesis. Expression is later more widespread, with strong expression in the nervous system. ASPP1 is a p53-binding protein that stimulates the apoptotic function of p53 in vitro. The down-regulation of ASPP1 and a family member ASPP2 is frequently detected in human breast carcinomas, suggesting a possible role of ASPP proteins as tumor suppressors.29 However, it remains to be investigated whether ASPP1 plays an essential role in endothelial cells. Further analysis will be required to address this issue.

Recent insights into the intimate developmental correlation between vascular and nervous systems have not only revealed their cross-talk but also suggested that the same molecular machinery may be involved in their developmental organization.41,42 In this study, we detected Hes1 expression in differentiated ES cells on an OP9 feeder cell layer by gene-trap insertion. Hes1 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor implicated as an inhibitor of neuronal differentiation.43 Hes1 is known to be a direct downstream target of Notch signaling.44 Recent reports showed that an active form of Notch1 or Notch4/int3 signaling induces the expression of HES1 in cultured human endothelial cells,45,46 implying the involvement of Hes1 in vascular development. In fact, ectopic expression of HES1 enhances network and cord formation of arterial endothelial cells.45 No vascular defect has been reported in Hes1 null mice47 and we have not analyzed the Hes1 gene-trap clone further. However, the newly described functions for Hes1 in endothelial cells in culture validate the gene-trap expression screen and suggest that further analysis of possible vascular defects in Hes1 mutant mice is warranted.

We used a “polyA trap” vector, IRESβgalNeo(-pA), for our gene-trap screening.22 Because this vector has a human β-actin promoter driving a neo gene, the drug selection is independent of the β-gal reporter. Compared with gene-trap vectors carrying a β-geo reporter that is a fusion transcript of β-gal and neo genes, IRESβgalNeo(-pA) can detect insertions in sites that are not expressed in undifferentiated ES cells. In addition, this vector has another characteristic feature, the “polyA trap.” This vector does not have a polyA signal following the neo gene, but has a splice donor sequence from the Pax2 gene. Thus, in order for a trapped cell to become G418 resistant, the endogenous polyA signal in the genome needs to be used, either by direct readthrough or by splicing into a downstream exon. This strategy ensures that G418-resistant clones are actually integrations in genes, whether or not the gene is expressed in ES cells. Although we found endogenous polyA signals of trapped genes in 3′ RACE products, we could not find any evidence that the Pax2 splice donor in this vector was used correctly, explaining the 3′ bias of the gene-trap events in our screen. Improvements of polyA trap vector design will be required to overcome this problem. Recently, we have developed our own vectors, which do not show this bias in integration sites, and have implemented this expression screening strategy on a large scale to identify endothelial-specific gene-trap clones. This resource, which includes gene-trap clones specific for endothelial cells as well as other cell types, can be searched by both sequence and expression patterns at http://www.cmhd.ca/sub/genetrap.asp.48 By using this new generation of gene-trap vectors, the gene-trap screening strategy described here can be useful to identify endothelial-specific genes and to analyze their function in mice.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 15, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0254.

Supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Terry Fox Funds of the National Cancer Institute of Canada. M.H. was a recipient of a Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute Ontario/Research and Development Challenge Fund Fellowship.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr Peter Gruss for the IRESβgalNeo(-pA) gene-trap vector; Drs Michelle Letarte, Yuki Kimura, Seiji Hitoshi, and Yojiro Yamanaka for helpful discussion; Lois Byers, Sue MacMaster, Ken Harpal, and Heather Hill for technical assistance. M.H. is grateful to Dr Shin-Ichi Nishikawa and Satomi Nishikawa for their initial supervision of ES cell differentiation culture.