Abstract

The use of leukemia cells as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in immunotherapy is critically dependent on their capacity to initiate and sustain an antitumor-specific immune response. Previous studies suggested that pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) cells could be manipulated in vitro through the CD40-CD40L pathway to increase their immunostimulatory capacity. We extended the APC characterization of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL for their potential use in immunotherapy in a series of 19 patients. Engaging CD40 induced the up-regulation of CCR7 in 7 of 11 patients and then the migration to CCL19 in 2 of 5 patients. As accessory cells, CD40L-activated BCP-ALL induced a strong proliferation response of naive T lymphocytes. Leukemia cells, however, were unable to sustain proliferation over time, and T cells eventually became anergic. After CD40-activation, BCP-ALL cells released substantial amounts of interleukin-10 (IL-10) but were unable to produce bioactive IL-12 or to polarize TH1 effectors. Interestingly, adding exogenous IL-12 induced the generation of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–secreting TH1 effectors and reverted the anergic profile in a secondary response. Therefore, engaging CD40 on BCP-ALL cells is insufficient for the acquisition of full functional properties of immunostimulatory APCs. These results suggest caution against the potential use of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells as agents for immunotherapy unless additional stimuli, such as IL-12, are provided.

Introduction

B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) is the most common form of cancer in children.1 Intensive multiagent chemotherapy and hemopoietic stem cell transplantation lead to cure in more than 80% of patients.1,2 Nonetheless, some patients are still resistant to standard therapies, which also have high and often unacceptable levels of acute and chronic organ toxicity and increased risk for secondary malignancies. Therefore, new strategies are needed to improve overall survival and to decrease treatment-associated morbidity. Immunotherapy could represent a complementary approach. Preclinical data show that whole tumor cells could potentially be used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to directly present known and unknown tumor-associated antigen (TAA) and to generate a specific immune response.3 The use of tumor cells as APCs in cancer immunotherapy is critically dependent on their capacity to initiate and amplify an antitumor-specific immune response. Successful T-cell–mediated immunity requires the expression of costimulatory molecules (B7 family and cytokines) by APCs and their migration to regional lymph nodes, where they come in close contact with T cells. Consequently, finding strategies to increase tumors cell immunogenicity is an intriguing challenge in cancer therapy.

BCP-ALL cells lack the expression of important costimulatory accessory molecules and are poor APCs4 for efficient T-cell activation. As previously demonstrated by our group5 and others,6-12 CD40 cross-linking on a variety of different leukemia types by CD40 ligand (CD40L) induces the up-regulation of the surface molecules CD40, CD80, CD86, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II, CD54, and CD58 and the secretion of chemoattractants CCL17 and CCL22.13,14 Published data show that engaging CD40 converts nonimmunogenic BCP-ALL cells into cells somehow able to induce the proliferation of alloantigen-specific T cells5,6 and the generation of autologous anti-ALL–specific cytotoxic T-cell lines from bone marrow (BM) specimens collected at diagnosis from patients with BCP-ALL.6,15 These observations suggest that BCP-ALL cells could be efficiently manipulated in vitro through the CD40-CD40L pathway to increase their immunostimulatory capacity. However, whether CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells acquire the full functional phenotype and capacities of APC is still unknown.

In this study we show that activating pediatric BCP-ALL cells with CD40L induced the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and of the chemotactic receptor CCR7, followed, in selected cases, by migration to the chemokine CCL19. CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells, however, were unable to produce bioactive interleukin-12 (IL-12) or to generate T-helper 1 (TH1) effectors. In contrast, they produced substantial amounts of IL-10 and promoted T-cell anergy. Interestingly, adding IL-12 after CD40L stimulation induced the generation of TH1 interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–secreting effectors and reversed the anergic state.

These observations suggest that, even though CD40 engagement on BCP-ALL cells promotes the acquisition of some phenotypic and functional properties of APCs, BCP-ALL cells do not acquire complete APC functionality and are, therefore, unlikely to induce a protective antileukemia-specific immune response when used as cancer vaccines, unless appropriate additional signals are provided.

Patients, materials, and methods

Cells

Bone marrow (BM) cells were collected at diagnosis from 19 children with BCP-ALL. In all patients, blast infiltration was greater than 80% and more than 90% of the blasts expressed CD19 antigen and lacked surface immunoglobulin (sIg). Human bone marrow stromal cells (HBMSs) were obtained from healthy donors at transplantation; normal peripheral blood (PB) samples were obtained from healthy volunteers. Mononuclear cells (MNCs), from BM or PB samples, were obtained after density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) and then 3 washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. T cells used for allogeneic proliferation were separated from MNCs by further centrifugation on Percoll gradient, as previously described.16 Dendritic cells (DCs) used as control were obtained from PB monocytes cultured for 7 days in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) in the presence of 50 ng/mL granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and 20 ng/mL IL-13, as previously described.17 All leukemia samples were cryopreserved in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 50% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Vials were first placed at –80° C for 24 hours and then were stored in liquid nitrogen. Thawed leukemia cells were used in all the experiments. The institutional review board approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from patients and their guardians.

HBMS cultures

HBMS layers were prepared as previously described.18 Briefly, BM MNCs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 10–6 M hydrocortisone (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO), 2 mM l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 33° C in 5% CO2 and 90% humidity and were fed every 7 days by replacing 50% of the supernatant with fresh complete medium. After confluent layers formed, cells were detached by treatment with trypsin (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD), washed once, and resuspended in fresh complete medium. Cells were then distributed into 24-well, flat-bottomed plates and were cultured until a confluent stromal layer grew.

BCP-ALL cell culture on HBMS layers

Thawed BCP-ALL blasts are fragile and are difficult to keep alive in culture conditions. Highly viable BCP-ALL blasts were maintained in vitro by coculture on HBMS, as previously described.18 Leukemia cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS at a final concentration of 2 × 106/mL. One milliliter of the suspension was seeded onto HBMS cells previously washed twice with PBS. For CD40 cross-linking, BCP-ALL cells were cocultured with CD40L-transfected J558 cell line at a 2:1 BCP-ALL/CD40L+J558 cell ratio. After 48 hours of culture, cells were detached by scraping, washed once in RPMI 1640 containing FBS, and passed through a 19-gauge needle to disrupt clumps.

In selected experiments (to use blast cells in mixed-leukocyte reaction [MLR] and T-cell anergy assay) to purify leukemia cells from contaminating stromal cells after coculture, 107 cells (BCP-ALL and stromal) were incubated with 20μL Fc receptor blocking reagent, 20 μL antifibroblast, 20 μL anti-CD4,and 20 μL anti-CD8–conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After 2 runs of immunoselection through a MS+ separation column, unlabeled cells were retained, and the purity of the leukemia population was checked with anti-CD19 antibody. Purity was always greater than 90%.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis

Phenotypic expression of surface molecules was determined by direct and indirect labeling using standard protocols. Cells were incubated with the following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD80, CD86 (Caltag, San Francisco, CA), and anti-CCR7 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). For indirect labeling, FITC-conjugated goat antimouse F(ab')2 immunoglobulin antibody was obtained from DAKO (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark). Irrelevant isotype-matched antibodies were used as negative controls. Ten thousand cells were acquired with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). We arbitrarily considered any increase in the percentage of positive cells that was greater than 10% as an efficient CD80 and CD86 up-regulation.6 Paired Student t test was used to determine significant effects of CD40L stimulation on molecular expression profiles of costimulatory molecules.

Chemotaxis assay

Cell migration was evaluated using a chemotaxis chamber (Neuroprobe, Pleasanton, CA) and polycarbonate filter (5 μm pore size; Neuroprobe) as previously described.19 CCL-19 (100 ng/mL) was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated at 37° C for 180 minutes. Results are expressed as the mean number of migrated cells in 5 high-power fields (1000 ×) following the formula: net migration = migration in the presence of chemoattractant – migration in medium. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

MLR

Immunomagnetic purified BCP-ALL cells and control DCs were added in graded numbers to 2 × 105 purified allogeneic T cells from cord blood in 96-well, round-bottomed microtest plates. T lymphocytes from normal PB were depleted of autologous monocytes by Percoll gradient. Each group of experiments was performed in triplicate. [3H]-Thymidine incorporation was measured on day 5 by 18-hour pulse (5 Ci/mmol [18.5 Bq/mmol]; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Cytokine production detected by ELISA

BCP-ALL cells and control DCs (1 × 106/mL) were incubated in the absence of stimuli or with the CD40L-transfected J558 cell line. After 48 hours supernatant was collected, and IL-12p70, IL-12p40, and IL-10 cytokines were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously described.20

RQ-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from BCP-ALL cells, CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells, and DCs by standard phenol-chloroform extraction. cDNA was synthesized from 1.0 μg total RNA as previously described.21 For IL-10, IL-12p35, and IL-12p40 amplification, predeveloped TaqMan reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used. IL-23p19–specific primers and fluorescence probe were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA): forward primer, 5′-TTCTCTGCTCCCTGATAGCCC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-AGTCTCCCAGTGGTGACCCTC-3′; fluorescence probe, 5′-6FAM CTTCATGCCTCCCTACTGGGCCTCA XTP-3′.

For real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) analysis, the TaqMan PCR core reagent kit was used (Applied Biosystems). Reaction mixtures of 25 μL contained 2.5 μL TaqMan buffer A, 300 nM primers, 200 nM probe, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold, and 0.1 cDNA preparation. The amplification protocol consisted of 10 minutes at 95° C, followed by 50 cycles of 15 seconds at 95° C and 1 minute at 60° C. RQ-PCR amplification was performed on the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). All samples were tested in triplicate. To correct for the quantity and quality (amplification ability) of cDNA, the ABL transcript was amplified. Standard curves for each target and ABL cDNAs were established by amplifying a 10-fold serial dilution of cDNA in water. Quantitative values obtained for the target cDNA were divided by the value for ABL. For each sample, the amount of each target cRNA synthesized from CD40L-stimulated cells was expressed as an n-fold difference relative to the amount of target cRNA synthesized from nonstimulated cells.

Polarization of naive T lymphocytes into TH1orTH2 effectors

Lymphocytes enriched in naive T cells were obtained from cord blood of healthy deliveries by panning on CD6-coated plastic plates. T cells (1 × 106/mL) were cocultured for 6 days with BCP-ALL cells and with CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells at a ratio of 4:1. At the end of the incubation period, cells were collected and stimulated with phorbol-12 myristate-13 acetate (PMA; 50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 μg/mL) for 6 hours. Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) was added during the last 2 hours of culture. Cells then were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with saponin. Fixed cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti–IFN-γ (Becton Dickinson) and phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–IL-4 mAb (Becton Dickinson) and were analyzed using FACS (Becton Dickinson).

T-cell anergy assay

Allogeneic T cells were first cocultured with irradiated immunomagnetic purified BCP-ALL cells or with control DCs (5:1 ratio). Five days later T cells were collected, purified by panning on CD6-coated plastic plates, extensively washed, and rested in medium without exogenous stimuli. After 2 days, T cells were cultured again with the same leukemia cells used in the first stimulation or with CD40L-activated DCs as immunostimulatory APCs. In 3 patients (unique patient numbers [UPN] UPN2, UPN17, UPN18), T cells were also cultured with leukemia cells of the respective patient in the first priming. To study the effect of exogenous IL-12 on T-cell anergy, 20 ng/mL IL-12 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells. [3H]–Thymidine incorporation was measured after 3 days of culture.

Results

Immunophenotype of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells

We5 and others 6,22-24 previously reported that CD40 cross-linking on BCP-ALL cells by CD40L could induce a significant upregulation of costimulatory molecules. The activation induced by CD40L transfectants was confirmed during this study by analyzing the expression of CD80 and CD86 on BCP-ALL cells. None of the thawed BCP-ALL cells (19 patients) expressed CD80, whereas in 4 patients (UPN4, UPN5, UPN7, UPN11) CD86 was already expressed (10%-40%). Table 1 shows that coculture on HBMS induced the up-regulation or de novo expression of costimulatory molecules on BCP-ALL cells. Engaging CD40 further increased CD80 and CD86 expression. The mean value of CD80-expressing BCP-ALL cells was 13.5% compared with 27.7% for CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells (P = .06). The mean value of CD86-expressing BCP-ALL cells was 33.5% compared with 51.7% for CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells (P = .04).

Migration of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in response to CCL19

We examined the functional activity of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells. A major function of an antigen-bearing APC is to migrate to lymphoid organs, where it comes in close contact with T cells. This travel is guided by chemokines expressed along the lymphatic vessels (CCL21)25 and within the lymph nodes (CCL19),26 interacting with CCR7 expressed on the APC itself.

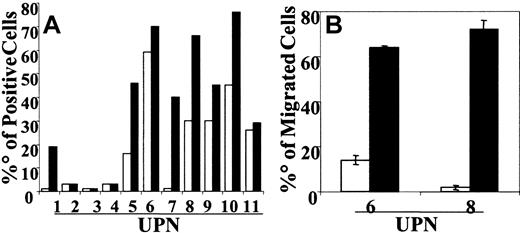

CCR7 expression was examined in 11 patients with BCP-ALL. Immediately after thawing, BCP-ALL cells did not usually express CCR7. In 3 patients (UPN8, UPN10, UPN11) cells already expressed low levels (less than 20% positive cells) of CCR7. After culture on HBMS, the up-regulation or de novo expression of CCR7 was observed in 6 patients (range, 20%-60%). The mean percentage of CCR7-positive cells before CD40L stimulation was 19.55% and increased to 36.18% after CD40 engagement (Figure 1A). In selected experiments we tested the capacity of CCR7+ BCP-ALL cells (UPN6, UPN7, UPN8, UPN10, UPN11) to migrate in response to CCL19. Cells from 2 patients (UPN6, UPN8) significantly migrated in response to CCL19 only after CD40 engagement (Figure 1B).

CCR7 expression and migration of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in response to CCL19. BCP-ALL cells were cocultured on HBMS stroma. For CD40 cross-linking, BCP-ALL cells were cocultured with the CD40 ligand–transfected J558 cell line. (A) After 48 hours of culture, BCP-ALL cells (□) and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL (▪) were detached by scraping and were washed and stained with anti-CCR7 mAb. Results are expressed as the percentage of positive cells in the gate of viable cells. (B) Results show net numbers of migrated cells in response to CCL19 (100 ng/mL) and are shown as mean ± SE of 5 microscope fields. Migration was evaluated in a modified Boyden chamber for 90 minutes.

CCR7 expression and migration of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in response to CCL19. BCP-ALL cells were cocultured on HBMS stroma. For CD40 cross-linking, BCP-ALL cells were cocultured with the CD40 ligand–transfected J558 cell line. (A) After 48 hours of culture, BCP-ALL cells (□) and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL (▪) were detached by scraping and were washed and stained with anti-CCR7 mAb. Results are expressed as the percentage of positive cells in the gate of viable cells. (B) Results show net numbers of migrated cells in response to CCL19 (100 ng/mL) and are shown as mean ± SE of 5 microscope fields. Migration was evaluated in a modified Boyden chamber for 90 minutes.

Cytokine production by CD40L BCP-ALL cells

Cytokine production by APCs is of major importance for the initiation, amplification, and orientation of the immune response. We tested the ability of BCP-ALL cells from 19 patients to produce IL-12p70, IL-12p40, and IL-10. Cytokine production was measured in supernatants of BCP-ALL cells treated with CD40L transfectants for 48 hours. Because BCP-ALL cells were cultured on HBMS, we also detected the production of these cytokines in supernatants of HBMS alone. Stromal cells never produced IL-12p70 or IL-12p40, but, in 2 of 5 patients, we observed the production of low levels of IL-10 (100 pg/mL or less) (data not shown). For this reason, in these 2 patients, the spontaneous production of IL-10 by stroma was subtracted from that obtained from BCP-ALL cells. None of the nonstimulated BCP-ALL cells in all 19 patients produced IL-12p70, IL-12p40, or IL-10 (not shown). After CD40L activation, BCP-ALL cells from all the patients still could not produce IL-12p70 (Table 2). In contrast, in 15 patients they produced substantial levels of IL-10 (mean, 288 pg/mL; range, 150-750 pg/mL). We also tested the production of the soluble p40 subunit. After CD40L activation, BCP-ALL cells produced p40 subunits, in sometimes at very high levels (mean, 2280 pg/mL; range, 100-12 900 pg/mL).

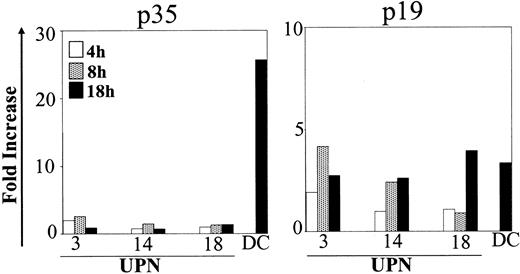

Cytokine expression was also detected by RQ-PCR. As shown in Figure 2, p35 transcripts did not increase in the different time points analyzed. In contrast p19, a subunit binding to p40 to form the newly described cytokine IL-23,27 was augmented after CD40L activation. Mean fold increases were 2.5 (range, 0.9-4.2) and 3.1 (range, 2.6-4.0) after 8 and 18 hours, respectively.

Kinetics of p35 and p19 expression in CD40L-activated BCP-ALL. BCP-ALL cells were cultured as indicated in Figure 1 and were stimulated with the CD40 ligand–transfected J558 cell line for different times (4, 8, and 18 hours). The RNA level was determined using RQ-PCR. The amount of each target cRNA synthesized from CD40L-stimulated cells was expressed as an n-fold difference relative to the amount of target cRNA synthesized from nonstimulated cells.

Kinetics of p35 and p19 expression in CD40L-activated BCP-ALL. BCP-ALL cells were cultured as indicated in Figure 1 and were stimulated with the CD40 ligand–transfected J558 cell line for different times (4, 8, and 18 hours). The RNA level was determined using RQ-PCR. The amount of each target cRNA synthesized from CD40L-stimulated cells was expressed as an n-fold difference relative to the amount of target cRNA synthesized from nonstimulated cells.

APC function and TH-polarizing activity of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells

We also extended the functional characterization of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells with respect to their ability to activate and polarize naive T lymphocytes into TH1 or TH2 effectors. To purify leukemia cells from contaminating stromal cells after coculture, in a selected series of 4 patients (UPN10, UPN6, UPN17, UPN18), leukemia cells were sorted by negative selection (see “Patients, materials, and methods”). The accessory cell function of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells was first tested in a classical MLR assay (Figure 3). Even at a low stimulator-responder (S/R) ratio (eg, 3:100), BCP-ALL cells were able to induce a significant proliferative response from allogeneic naive T cells. In some patients, immunostimulatory activity was comparable to that of myeloid dendritic cells (DCs), differentiated in vitro from normal monocytes, used as reference-optimal APCs. CD40 cross-linking on leukemia cells did not significantly modify their ability to activate T-cell proliferation.

Accessory cell function of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in MLR. Leukemia cells were sorted immunomagnetically and were cocultured with CD40L-transfected J558 cell line for 48 hours. (top) Untreated BCP-ALL cells and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at 3%. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13 and were activated for 48 hours with CD40 ligand–transfected J558. (bottom) Untreated (□) and CD40L-activated (▪) BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at the indicated concentrations. Results of 3 representative experiments are shown. Proliferation of naive T cells (2 × 105/well) was assessed using [3H]-thymidine uptake during the last 18 hours of a 5-day experiment. Results show the mean ± SD of the 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.

Accessory cell function of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in MLR. Leukemia cells were sorted immunomagnetically and were cocultured with CD40L-transfected J558 cell line for 48 hours. (top) Untreated BCP-ALL cells and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at 3%. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13 and were activated for 48 hours with CD40 ligand–transfected J558. (bottom) Untreated (□) and CD40L-activated (▪) BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at the indicated concentrations. Results of 3 representative experiments are shown. Proliferation of naive T cells (2 × 105/well) was assessed using [3H]-thymidine uptake during the last 18 hours of a 5-day experiment. Results show the mean ± SD of the 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.

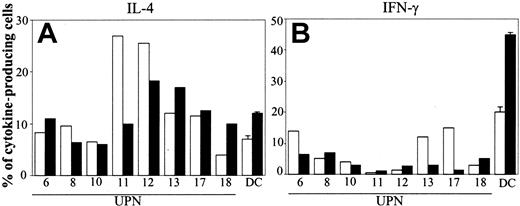

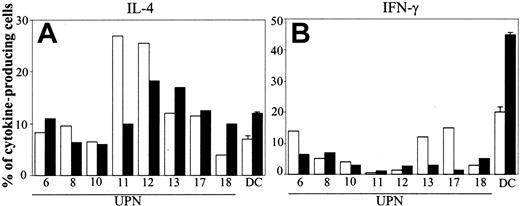

In 8 patients we tested cytokine production by T cells cocultured with BCP-ALL cells. Nonstimulated BCP-ALL cells had poor capacity to induce TH1 polarization (mean value of IFN-γ–producing cells was 7%; Figure 4, right panel). After CD40L activation, the TH1-polarizing activity of leukemia cells was not increased overall and was actually reduced in 3 of 8 patients (Figure 5, right panel). Induction of TH2 polarization by BCP-ALL cells was higher compared with the proportion of TH1 effectors. The mean value of IL-4–secreting cells was 13% (Figure 4, left panel), and, except in 1 patient who had fewer IL-4–producing cells, engaging CD40 did not substantially modify the polarization capacity of BCP-ALL cells (mean value, 12%).

Polarization of naive T cells into TH1 or TH2 effectors by CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells. After 1 day of culture, BCP-ALL cells were activated (or not) by CD40 ligation. Cytokine production by purified cord blood T lymphocytes after coculture with BCP-ALL cells (□) or CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells (▪) was assessed by intracellular staining of IL-4 (A) and IFN-γ (B) with specific mAb after cell permeabilization. Data are expressed as the percentage of cytokine-producing cells. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13. Data from normal DCs refer to mean ± SD of 3 different experiments.

Polarization of naive T cells into TH1 or TH2 effectors by CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells. After 1 day of culture, BCP-ALL cells were activated (or not) by CD40 ligation. Cytokine production by purified cord blood T lymphocytes after coculture with BCP-ALL cells (□) or CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells (▪) was assessed by intracellular staining of IL-4 (A) and IFN-γ (B) with specific mAb after cell permeabilization. Data are expressed as the percentage of cytokine-producing cells. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13. Data from normal DCs refer to mean ± SD of 3 different experiments.

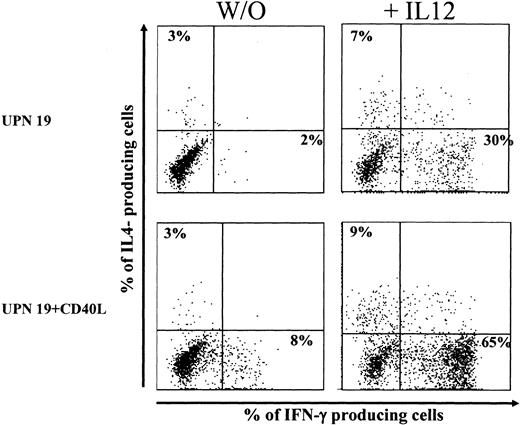

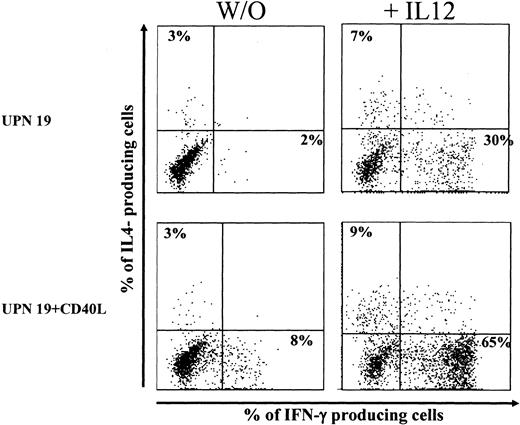

Effect of exogenous IL-12 on TH1-polarizing activity of BCP-ALL cells. BCP-ALL cells or CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were cocultured with purified cord blood T lymphocytes in the presence or absence of 20 ng/mL IL-12. After 6 days, IFN-γ and IL-4 production by T cells was assessed by intracellular staining. Data are expressed as the percentage of cytokine-producing cells.

Effect of exogenous IL-12 on TH1-polarizing activity of BCP-ALL cells. BCP-ALL cells or CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were cocultured with purified cord blood T lymphocytes in the presence or absence of 20 ng/mL IL-12. After 6 days, IFN-γ and IL-4 production by T cells was assessed by intracellular staining. Data are expressed as the percentage of cytokine-producing cells.

In a small series of experiments, IL-12 was added at the initiation of the coculture, and it stimulated a potent TH1 polarization. Results of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 5. In the presence of exogenous IL-12 (20 ng/mL), the proportions of IFN-γ–producing cells activated by unstimulated BCP-ALL cells and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were augmented from 2% to 30% and from 8% to 65%, respectively. Mean percentage values (± SD) of IFN-γ–producing cells (3 donors tested) were 3 ± 2 and 43 ± 20 (before and after the addition of IL-12) for unstimulated BCP-ALL and 8 ± 7 and 39 ± 18 (before and after the addition of IL-12) for CD40L-activated BCP-ALL.

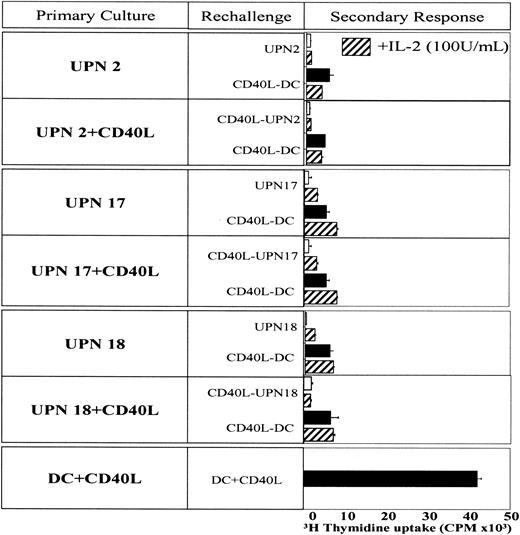

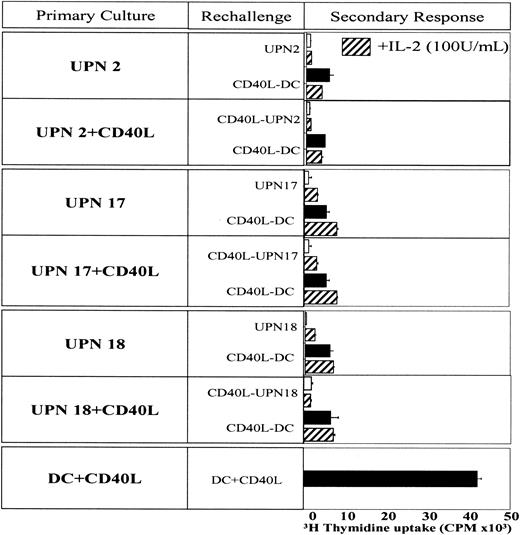

CD40L-BCP ALL cells induce hyporesponsive T cells

Given that long-lasting T-cell activation is a major requirement for specific immunity, we next tested the ability of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells to sustain T-cell proliferation over time. In these experiments, allogeneic T cells were first cocultured with immunomagnetically sorted leukemia cells for 5 days. Then the cells were extensively washed and restimulated in a second coculture with the leukemia cells used in the first stimulation or with CD40L-activated DCs, used as fully competent APCs (Figure 3). BCP-ALL cells or CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells initially triggered the proliferation of allogeneic T cells. Leukemia cells, however, were unable to sustain long-term proliferation. T cells that were primed with BCP-ALL cells or with CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were poor responders when rechallenged with the same leukemia cells (Figure 6). This state of anergy was not overcome by restimulating T cells with fully competent DC or by adding IL-2 (100 U/mL). In contrast, as expected, T cells first activated by CD40L-activated DCs had the potential to proliferate when rechallenged a week later with the same APCs (Figure 6). Thus, T cells primed by BCP-ALL cells, even after CD40L engagement, are hyporesponsive to a second challenge.

Induction of T-cell anergy induced by BCP-ALL cells. T cells were first primed with sorted BCP-ALL cells or control DCs for 5 days. T cells were extensively washed and restimulated in a second coculture with the same BCP-ALL cells (□) or control DCs (▪) used in the first stimulation in the absence or in presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 (▨) . Results show the mean ± SD of 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.

Induction of T-cell anergy induced by BCP-ALL cells. T cells were first primed with sorted BCP-ALL cells or control DCs for 5 days. T cells were extensively washed and restimulated in a second coculture with the same BCP-ALL cells (□) or control DCs (▪) used in the first stimulation in the absence or in presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 (▨) . Results show the mean ± SD of 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.

We hypothesized that the lack of IL-12 could be implicated in this anergic response. IL-12 was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP ALL cells. Adding IL-12 reverted T-cell anergy in the 3 patients tested (Figure 7). However, IL-12 had to be present during priming and during rechallenge. In 1 patient (UPN17), the presence of IL-12 only during the priming phase was sufficient to induce significant proliferation. Taken together, these findings indicate that T-cell anergy induced by CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells can be overcome by immune stimulatory cytokine IL-12. Similar results were obtained when BCP-ALL cells were used as APCs (data not shown).

Effect of exogenous IL-12 on secondary response. T-cell anergy assay was conducted as described in the legend to Figure 6. IL-12 (20 ng/mL) was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP ALL cells. Proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake after a 3-day culture.

Effect of exogenous IL-12 on secondary response. T-cell anergy assay was conducted as described in the legend to Figure 6. IL-12 (20 ng/mL) was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP ALL cells. Proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake after a 3-day culture.

Discussion

A compelling rationale for using whole tumor cells as vaccines in cancer immunotherapy is that they have the potential to display the widest range of tumor antigens to the host's T-cell repertoire and, as a consequence, theoretically generate a large number of tumorreactive T cells. A major obstacle to using BCP-ALL cells as vaccines is their poor immunogenicity4 because they lack the expression of important costimulatory accessory molecules necessary for efficient T-cell activation. In normal B cells, activating the CD40-CD40L pathway drives differentiation, proliferation, and immunoglobulin class-switching while it prevents B-cell apoptosis.28 Moreover, CD40L is required to activate all kinds of APCs, including B-cells and DCs, to produce IL-12.29,30 CD40 crosslinking on BCP-ALL cells by CD40L can induce a number of morphologic and functional changes of BCP-ALL blasts. We and others5,6,22-24 have shown that CD40-activation of BCP-ALL cells induces up-regulation of the surface markers CD40, CD80, CD86, MHC class I and II, CD54, and CD58 and have confirmed it in this paper regarding the B7 family.

When manipulated whole tumor cells are used as cancer vaccines, 2 different biologic mechanisms can be hypothesized at the time of vaccine injection: either they work as complete APCs—presenting the appropriate antigens, migrating to the regional lymph nodes, and activating circulating T cells—or they simply work as a source of potential TAA. In the latter, the simultaneous delivery of a proinflammatory signal, such as CD40L31 or GM-CSF,32 can efficiently attract and subsequently activate the endogenous professional APCs in the derma (such as Langerhans cells), which, in turn, migrate to T-cell areas of lymph nodes. It has been postulated that CD40-activated BCP-ALL cells may work as professional APCs. We further extended the characterization of these cells with the aim of demonstrating whether they may be used as professional APCs in vivo as cancer vaccines.

In the present study, we have analyzed the chemotactic response, cytokine profile, and ability to polarize naive T lymphocytes of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells derived from pediatric patients. Engaging CD40 on BCP-ALL cells induced the de novo expression or up-regulation of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Migration to regional lymph nodes, which is primarily guided by the axis CCR7/CCL19, is a major requirement for eliciting primary adaptive immunity.33 In 2 selected cases (of 5 tested), we observed a functional in vitro chemotactic response to CCL19 after CD40 activation. It should be noted that unstimulated BCP-ALL cells from these 2 patients already expressed considerable levels of CCR7, but these receptors were not functional. The expression of nonfunctional chemokine receptors or inactive downstream signaling has been described in B cells and in other cells.34,35 Therefore, it is interesting that CD40 ligation rescued the migratory response to CCL19, at least in these 2 subjects.

When tested as accessory cells in MLR assays, unstimulated BCP-ALL cells were able to elicit the proliferation of allogeneic naive T cells, even at a low stimulator-responder ratio (3:100). Cross-linking CD40 on BCP-ALL cells did not significantly increase T-cell proliferation. CD40 engagement, however, did modify the cytokine production profile of BCP-ALL cells and their T helper–polarizing ability. In fact, in most of the analyzed patients, CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells produced considerable levels of IL-10, which was never released by unstimulated leukemia cells. IL-10 is a potent immunosuppressive cytokine that inhibits IL-12 production and several functions of TH1 lymphocytes and professional APCs.36-39 Moreover, it has been shown that naive T cells activated in the presence of IL-10 or IL-10–producing APCs either acquire tolerance or differentiate into regulatory T cells.40,41 In this study, we also followed the proliferative capacity of allogeneic T cells primed by CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells over time. In 3 of 3 patients tested, T cells became anergic to a second challenge and lost the ability to respond to fully immunostimulatory APCs (ie, CD40L-activated myeloid DCs). IL-10 may not be the only factor involved in this phenomenon. One of these 3 patients was not an IL-10 producer (at least as indicated after 48-hour culture) but had very low up-regulation of costimulatory molecules. Moreover, unstimulated BCP-ALL cells not producing IL-10 also induced T-cell anergy. Thus, the low expression of B7 molecules and IL-10 production are among the possible factors cooperating in the induction of T-cell unresponsiveness.

Another major finding of this study is the inability of CD40L-stimulated BCP-ALL cells to express IL-12p70. IL-12p70 was not produced even after combined stimulation with CD40L and IFN-γ (data not shown). Although the presence of IL-10 is likely to suppress IL-12p70, it should be noted that the defective release of IL-12p70 was also found in those patients with low or undetectable IL-10 production. Therefore, other IL-10–independent mechanisms could be involved. Consistent with the absence of IL-12p70 production, TH1 polarization of naive T cells activated by BCP-ALL cells was inefficient, even after CD40 activation. Studies in IL-12–deficient mice have demonstrated the essential role of IL-12 in inducing TH1 responses.42,43 IL-12 is composed of a p35 and a p40 subunit, and the secretion of free monomeric and homodimeric p40 is 10- to 1000-fold greater than that of heterodimeric bioactive IL-12.44 BCP-ALL cells produced the soluble p40 subunits after CD40L activation, sometimes at very high levels. Studies in mice have demonstrated an antagonistic effect of the p40 homodimer on IL-12 bioactivity by competition on the β1 subunit of the IL-12 receptor (IL-12R).45 However, in humans, the IL-12p40 homodimer has lower affinity for IL-12R, and an antagonistic effect was not described. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the p40 subunit binds to another novel protein, p19, and generates a heterodimeric molecule designated IL-23.27,46 Human IL-23 has some biologic activities similar to those of IL-12 (proliferation of memory T cells), but it has lower activity on IFN-γ production by naive and memory T cells.27,46 Using RQ-PCR, we demonstrated a 4-fold increase of p19 expression after CD40 stimulation. Whether IL-12p40 produced by CD40-activated BCP-ALL cells associates with p19 is still unknown because ELISA specific for IL-23 is not yet available. Nevertheless, the TH1-polarizing activity of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells remains low, even in the presence of a putative IL-23. Using RQ-PCR, we found that IL-12p35 was not up-regulated after CD40 engagement, confirming ELISA results for IL-12p70.

The inability of BCP-ALL cells to produce a bioactive form of IL-12 even after CD40 stimulation is a major obstacle for vaccination therapy. Adding exogenous IL-12 to the coculture of naive T cells with BCP-ALL cells promoted impressive TH1 polarization in 3 of 3 patients tested and reversed the anergic T-cell profile in a secondary response. Therefore, adding IL-12 is sufficient to generate a TH1 response in this system and to overcome possible suppression factors. These results indicate that the predominant TH2 response induced by CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells may be attributed to the lack of IL-12.

Other groups have reported that BCP-ALL cells activated by CD40L secrete soluble factors that may negatively interfere with an immune response. After CD40 activation, BCP-ALL cells produced copious amounts of the T-cell chemoattractants CCL17 and CCL22.14 These chemokines are ligands for CCR4, a receptor preferentially expressed on TH2 lymphocytes, regulatory T cells, and naive T cells.47-50 In contrast, leukemia cells did not produce TH1/NK cell–attracting chemokines such as CXCL10.51 The secretion of factors recruiting TH2 lymphocytes, T regulatory T cells and naive T cells is advantageous for tumor survival and immune escape.

Previous studies have looked at the immunogenicity of BCP-ALL cells activated by CD40L.6-8 In apparent contrast with the results of our study, Cardoso et al6 reported the in vitro generation of leukemia-specific cytotoxic T-cell lines. Their culture system involved bulk bone marrow as a source of leukemia cells and repeated stimulations and clonal amplification to select for cytotoxic progenitors. The possibility that other cells (such as mesenchymal stromal cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, or monocytes) present in the marrow could have provided costimulatory signals or might have exerted some APC activity cannot be excluded. As a matter of fact, cytotoxic T-cell lines could not be generated from the peripheral blood of the same patients.6 These considerations also apply to our previous finding in pediatric patients with BCP-ALL in an autologous setting.5 In fact, when leukemia cells, previously stimulated with soluble trimeric CD40L, were cocultured with autologous T cells isolated from BM specimens, IFN-γ secretion was detected to various extents. These responder leukemia-reactive autologous T cells probably represented low-frequency precursors already present in the BM that had been somehow “educated” to recognize leukemia-associated antigens (presented by BM cells with APC capacities). Conversely, in our current set of experiments, we used naive T cells isolated from cord blood specimens or allogeneic T cells that had never been exposed to any leukemia-associated antigens. Under these culture conditions, the results of our study clearly show that CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells are unable to polarize IFN-γ–producing effectors and to sustain prolonged T-cell expansion. Thus, when solely activating the CD40 pathway on BCP-ALL cells, without the addition of TH1-polarizing cytokines, leukemia cells are likely to evade and divert a potentially protective immune response. In addition, even if cytotoxic effectors are the ultimate effectors in cell-mediated antitumor immunity, it is now well established that tumor-specific TH1 lymphocytes with memory properties are absolutely required to sustain a long-lasting cytotoxic response.45

In vivo results observed when injecting leukemia or other tumor cells in combination with CD40L in mice and in humans11,52,53 further demonstrate that the most relevant in vivo factor for an efficient cancer vaccine strategy is likely to be the recruitment and activation of resident APC professional DCs (of which CD40L is one of the most potent stimulation factors) rather than the acquisition of APC functions by the tumor cells themselves. This has been elegantly demonstrated in mice when using cancer vaccines composed of CD40– leukemia cells (not presenting up-regulation of any costimulatory molecule), together with fibroblasts transduced to express the CD40L molecule.11 In this case, the protective effect observed when subsequently challenging the mice with unmanipulated tumor cells at a distal site was solely explained by the recruitment and activation of professional resident cutaneous APCs able to take up and present antigens by tumor apoptotic bodies.

In conclusion, we have shown that the one and only activation of CD40 on BCP-ALL cells by CD40L generates tolerogenic APCs. These APCs were unable to produce IL-12p70, secreted considerable amounts of IL-10, did not polarize TH1 effectors, and induced T-cell anergy. Our observations suggest caution against using CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells as possible in vitro stimulators for generating leukemia-reactive cytotoxic T cells to be adoptively transferred into patients. Our results also suggest that activating the singular CD40 pathway in BCP-ALL cells is not enough to generate complete and efficient APCs to be used for cancer vaccines, and they indicate that appropriate additional stimuli are needed to induce a protective leukemia-specific immune response. Interestingly, after its addition, IL-12 showed a potent ability to induce TH1 effectors and to overcome T-cell anergy, possibly indicating a good molecule to be used in vitro to produce a specific antileukemia immune response.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 4, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3762.

Supported in part by grants from the Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (A.B.), Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Universitá e della Ricerca (MUIR)/Cofinanziamento (COFIN) 2003, prot. 2003069141-005, the Fondazione M. Tettamanti, Monza, and Progetti di Ricerca Finalizzata Ministero della Salute RF202/02 (A.B). G.D. was supported by the Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC) fellowship. V.M. is a graduate student of the international PhD program in molecular medicine of Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

![Figure 3. Accessory cell function of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in MLR. Leukemia cells were sorted immunomagnetically and were cocultured with CD40L-transfected J558 cell line for 48 hours. (top) Untreated BCP-ALL cells and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at 3%. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13 and were activated for 48 hours with CD40 ligand–transfected J558. (bottom) Untreated (□) and CD40L-activated (▪) BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at the indicated concentrations. Results of 3 representative experiments are shown. Proliferation of naive T cells (2 × 105/well) was assessed using [3H]-thymidine uptake during the last 18 hours of a 5-day experiment. Results show the mean ± SD of the 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/3/10.1182_blood-2003-11-3762/6/m_zh80150464540003.jpeg?Expires=1769119315&Signature=x7Lfpgtd0ejULS~eiCTpRoZmMD4IHpPmBiE4d1ukxgDOLm2jAn7jmfFwErwxjbifSDpMDXhIW95sjUyh-aZT26UrMvChfZKopUMuxZmxyYlkdjYyG0EouhzvFPg-~c6hmN5WgtlxdJqgpKCmQmSecQrToyWgUaEP~EetGIdxUoIVLEcWPnoRe8yJ2B8VDIILvk9k2UBfb9SxRrINw0nUTFI5uBlZcm4SWYsKTdn0bPyrS2iw~4karqhOSdQqP5GcO9zrj8vmDFRXJqRL~P~gwLPbX66BKWP3vAIHCXv32t8AJoiiW6Jt7OgDMeksP707xwBR-GLAYU-uwGjLwIt~Xg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Effect of exogenous IL-12 on secondary response. T-cell anergy assay was conducted as described in the legend to Figure 6. IL-12 (20 ng/mL) was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP ALL cells. Proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake after a 3-day culture.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/3/10.1182_blood-2003-11-3762/6/m_zh80150464540007.jpeg?Expires=1769119315&Signature=Xfohy8rm-Yv-HfJcXE6Ch6ukh6Rr39dIGtOnp8BBuVvfYS0spfhUPU0unBUU9165d04b4q~mQ875J1Z~gq2ywkhaf3RMc50MIuPoPjGpfEATAfILqKKxDvgY9vPOtF70vZy1OJdiDZwugXQ2uIPIQRkAOkHQ9xC4uUzW1HmGZEUu5gCBsN3IR23sMduFgiPGzEXLHmDMdN3wTv-BwQBZISoQmk1XhgaZAnEuYm6v3a0323wPGUJCa-81IXjAMxXG~bH0xTdwCewio8nLjMn7nZf9a9mHxPhB90WR7v06bjnisAiQmJvhcSCC2n0NjcQzckYs0XUCJSAf5h5jRHCHCA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Accessory cell function of CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells in MLR. Leukemia cells were sorted immunomagnetically and were cocultured with CD40L-transfected J558 cell line for 48 hours. (top) Untreated BCP-ALL cells and CD40L-activated BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at 3%. Normal DCs were differentiated from monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF + IL-13 and were activated for 48 hours with CD40 ligand–transfected J558. (bottom) Untreated (□) and CD40L-activated (▪) BCP-ALL cells were used as stimulators at the indicated concentrations. Results of 3 representative experiments are shown. Proliferation of naive T cells (2 × 105/well) was assessed using [3H]-thymidine uptake during the last 18 hours of a 5-day experiment. Results show the mean ± SD of the 3H thymidine uptake of 3 replicates.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/3/10.1182_blood-2003-11-3762/6/m_zh80150464540003.jpeg?Expires=1769479188&Signature=i2UmPaxsswXMT4F~zQtspRb9aDa0vshJfP5wiIoy7kv-WBTO-TTpmXrdrZsoa311A48uzJho2-ytAl9P2C05t9HDaETLmNCoJZmlZbklW7HXAR6kh~ILFRwgdBeev5pMLGCWXNtIF5Y-MwZGaAkYoliQo9rJlUKNStdKFU69GhonlZJePBF50hgOK8mJ5ytxrpYksaC8ZDZOTI-X2X34~HVqV9w3q0Mv2oLPKMx278fEjFI6KXWNcJpGGaq~zhQXhIYHf~UWiDrnpq5HF5qrIf3Koo-rKb~4ZJg-gttsS~bY64n~w13ftOiekR5~MEaTePCasRwUlwirK6haTKCQaQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Effect of exogenous IL-12 on secondary response. T-cell anergy assay was conducted as described in the legend to Figure 6. IL-12 (20 ng/mL) was added during the first priming or rechallenge of T cells cultured with CD40L-activated BCP ALL cells. Proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake after a 3-day culture.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/3/10.1182_blood-2003-11-3762/6/m_zh80150464540007.jpeg?Expires=1769479188&Signature=cHOUiv8SSEyj7xQRjHtisd99ac5y5qDeNqyf2PWtIgj-f5RyGE~06naid4~xy1YWzg8zAkL614HXtGD-SsQa8DjLUAlR25Z9LBEDTtwQdJZP4BAKgmvbILPm8rCa07H-Wwo4g4COYKTXG9GGY25pxv2B2wHnAwMVKFV~qU5Bpn-47LdZC3yB9IYYAC9ej4v-X2uWRPQUXt8dORcfFaW8R0E0SHpHEd2iwslz~v7TXBYiQLSVm8hA-l0N2vILnWFJJps7K4ifKM55y3PBZhF5tdSghSvvyWEl-3qIvROec28pXvhlfPOgH2onbrXu5slIpa7gToUP9dZuJo~PoCpiGQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)