Abstract

A mutation of the iron transporter Nramp2 (DMT1, Slc11a2) causes microcytic anemia in mk mice and in Belgrade rats by impairing iron absorption in the duodenum and in erythroid cells, causing severe iron deficiency. Both mk and Belgrade animals display a glycine-to-arginine substitution at position 185 (G185R) in the fourth predicted transmembrane domain of Nramp2. To study the molecular basis for the loss of function of Nramp2G185R, we established cell lines stably expressing extracellularly tagged versions of wild-type (WT) or mutated transporters. Like WT Nramp2, the G185R mutant was able to reach the plasmalemma and endosomal compartments, but with reduced efficiency. Instead, a large fraction of Nramp2G185R was detected in the endoplasmic reticulum, where it was unstable and was rapidly degraded by a proteasome-dependent mechanism. Moreover, the stability of the mutant protein that reached the plasma membrane was greatly reduced, further diminishing its surface density at steady state. Last, the specific metal transport activity of plasmalemmal Nramp2G185R was found to be significantly depressed, compared with its WT counterpart. Thus, a singlepoint mutation results in multiple biosynthetic and functional defects that combine to produce the impaired iron deficiency that results in microcytic anemia.

Introduction

The systemic and cellular concentrations of iron, an essential element, must be tightly regulated to prevent insufficiency or toxic overload.1 Iron homeostasis is almost exclusively regulated at the level of absorption and storage. Iron is delivered to the bloodstream after traversing the duodenum, a result of the sequential action of an apical membrane transporter Nramp2 (also known as DCT1, DMT1, and Slc11a2) and a basolateral transporter, ferroportin (Fp-1, Slc40a1). In the bloodstream, iron is bound to transferrin, which is responsible for its delivery to peripheral tissues, in particular the liver (for storage) and the hemopoietic system (for hemoglobin biosynthesis). A large body of genetic and biochemical data, including direct transport measurements, have shown that transfer of iron across the duodenal apical membrane and its uptake into reticulocytes and other cell types are mediated by the same system, the divalent metal-proton symporter Nramp2. The transporter is an N-glycosylated protein composed of 12 transmembrane domains, capable of translocating a variety of divalent cations with comparable efficiency2-5 by a pH-dependent mechanism. The Nramp2 gene generates by alternative splicing 4 different mRNAs and corresponding protein isoforms, which differ in their 5′ and 3′ termini.6 Alternative splicing dictates the presence (in isoform I) or absence (in isoform II) of an iron-responsive element in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Nramp2 protein is expressed abundantly at the brush border of the duodenum, in specific epithelial cells, and in erythroid precursors, but is also expressed ubiquitously and at low levels in many cell types.7-9

Alterations in Nramp2 cause a very severe form of hypochromic, microcytic anemia in the Belgrade (b) rat and the mk mouse, which is characterized by impaired intestinal iron absorption and defective iron uptake into peripheral tissues.10-15 Intriguingly, both mk mice and b rats harbor the same glycine-to-arginine substitution at position 185 in the predicted fourth transmembrane domain of Nramp2.16,17 The mechanism by which Nramp2G185R impairs iron transport remains unclear. The introduction of a bulky, charged amino acid within a hydrophobic domain of Nramp2 could cause either an alteration of its symporter function, and/or affect its targeting or stability. Using heterologous expression in HEK293 cells, Su and colleagues18 reported that the G185R mutation alters the ability of Nramp2 to transport iron. In contrast, protein expression studies in wild-type (WT) and mutant animals led Canonne-Hergaux et al19 to conclude that Nramp2G185R is inadequately targeted or retained by the plasma membrane of enterocytes and reticulocytes from mk mice. Clearly, the molecular basis of microcytic anemia may be complex and remains incompletely understood.

Two features of Nramp2 have contributed to limit our understanding of its biologic properties. The intracellular distribution and traffic of the protein is complex, as it exists both in the plasma membrane and in endomembranes, recycling between these compartments.20 Second, the expression level of Nramp2 in native systems is modest, precluding biochemical analyses of protein processing and stability. To circumvent these limitations, we have stably expressed epitope-tagged forms of both WT and mutant Nramp2 in epithelial as well as nonepithelial cells. The tags were placed on an extracellular loop of the protein, enabling us to monitor the surface exposure and recycling rate of Nramp2 in viable cells and to normalize the rates of ion transport by the density of plasmalemmal symporters. Here we describe a comparison of the subcellular distribution, processing, stability, and transport properties of WT Nramp2 and Nramp2G185R. Our findings indicate that microcytic anemia results from a complex combination of defective biosynthesis, reduced stability, and impaired ion translocation ability of Nramp2G185R.

Materials and methods

Materials

Monoclonal mouse antibody (Ab) HA-11 to the influenza hemagglutinin epitope (HA) was purchased from BabCo (Berkeley, CA). Polyclonal Ab directed against the N-terminus of calnexin was the kind gift of Dr D. Williams (Department of Biochemistry, University of Toronto). Cy3-labeled antimouse Abs were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Alexa 488–coupled Ab, rhodamine-labeled transferrin, and calcein acetoxymethyl ester were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Peroxidase-coupled goat antimouse Ab was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). 35S-labeled methionine/cysteine was from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). CoCl2 and tunicamycin were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). MG132 was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

Cell culture

LLC-PK1 cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–F12 (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells in α–minimum essential medium (MEM), both supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). For immunofluorescence and video microscopy, the cells were plated on glass coverslips 48 hours before the experiment. Radiolabeling and biochemical analysis were performed on cells plated on 35-mm or 60-mm dishes.

LLC-PK1 or CHO cells were transfected with exofacially HA-tagged isoform I WT or Nramp2G185R and stable clones were selected as previously described.20 The GFP-KDEL vector, described earlier,20 was transfected using Fugene-6 (Roche, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions. When indicated, the cells were treated with cycloheximide (20 μg/mL), tunicamycin (2.5 μg/mL), MG132 (10 μM), or NH4Cl (15 mM), all in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% FCS, for the specified period of time.

Surface biotinylation and immunoblotting

Cells were grown to confluence on 35-mm dishes, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and once with cold borate buffer (boric acid 10 mM, NaCl 154 mM, KCl 7.2 mM, CaCl2 1.8 mM, pH 9). Next, cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimidobiotin (EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin; Pierce) in borate buffer for 15 minutes at room temperature. After this period, the remaining unreacted biotinylation reagent was scavenged by addition of 0.2 M glycine, followed by 2 washes in PBS. Total cell extracts were prepared by incubation for 10 minutes in 1 mL ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1% Triton X-100, plus a protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma) followed by centrifugation at 10 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Biotinylated proteins were extracted by incubation of 900 μL of the supernatant with 100 μL of a slurry of immobilized monomeric avidin beads (UltraLink Immobilized Monomeric Avidin; Pierce) for 1 hour at 4°C. Beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and bound proteins were eluted with 50 μL Laemmli buffer at room temperature for 30 minutes. Protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay from BioRad (Hercules, CA) and samples were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in 10% polyacrylamide gels followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA Ab. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) and exposed to Kodak film (Rochester, NY). The intensity of the bands was measured from scanned films using Image-J software (available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and, where indicated, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBST). The preparation was blocked for 30 minutes in medium containing 5% nonfat dry milk, then incubated with the primary antibodies (mouse anti-HA, 1:1000; rabbit anticalnexin, 1:1000) followed by secondary antibodies (1:1500) for 1 hour each. For experiments where live cells were exposed to antibodies and transferrinrhodamine, a 1:200 dilution for the anti-HA Ab and 35 μg/mL transferrinrhodamine were used. Cells were visualized on a Leica IRE DR2 microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) using a 100 × oil immersion objective. Digital images were acquired with an Orca II ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) driven by the Openlab 3 software (Improvision, Lexington, MA) installed on a Macintosh G4 computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA). Images were cropped, assembled, and labeled using Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA).

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation

Prior to radiolabeling, the cells were incubated with Met- and Cys-free DMEM for 1.5 hours at 37°C. The labeling pulse consisted of incubation for one hour in DMEM containing 0.2 mCi/mL (7.4 MBq/mL) of [35S]-Met and [35S]-Cys. After washing, the cells were incubated with DMEM supplemented with serum for the specified chase periods, and then extracted with lysis buffer for 10 minutes at 4°C. Samples were subjected to centrifugation at 15000 g (13 000 rpm) for 20 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for immunoprecipitation. The supernatants were precleared by overnight incubation with agarose beads at 4°C. Nramp2 was next immunoprecipitated for one hour at 4°C with a rabbit polyclonal anti-Nramp2NT Ab preloaded onto protein G–coupled beads (Ultralink Immobilized Protein G; Pierce). Beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer before solubilization in 50 μL2 × Laemmli buffer (30 minutes, room temperature). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, the gels were fixed in 20% ethanol, 10% acetic acid for 20 minutes at room temperature, incubated with the Amplify fluorographic reagent from Amersham for 30 minutes at room temperature, and dried on Whatmann paper (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) under vacuum at 70°C for 1.5 hours. Dried gels were exposed to autoradiographic films (Kodak X-OMAT LS; Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 12 hours to 3 days.

Colorimetric Nramp2 quantitation assay

For quantification of Nramp2 at the cell surface, LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with HA-tagged WT or Nramp2G185R were grown to confluence in 24-well plates. Cells were fixed on ice with PBS containing 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Following blocking with 5% goat serum in PBS, mouse anti-HAAb (1:500) was added for one hour at 4°C, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated donkey anti-mouse Ab (1:4000; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Bound peroxidase activity was quantified colorimetrically using O-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD substrate; Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cobalt uptake determinations

Uptake of Co2+ or Fe2+ was measured by microphotometry, monitoring the metal-induced quenching of the fluorescence of calcein as previously described in Touret et al.20 Measurements were performed using a Nikon Diaphot TMD inverted microscope coupled to the M Series dual-wavelength illumination and recording system from Photon Technologies (South Brunswick, NJ). We used a 490-nm excitation wavelength, a 510-nm dichroic mirror, and a 520-nm emission wavelength. Cells grown on coverslips were incubated in a NaCl-based medium (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM glucose, and 15 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 7.3) with 2 μM of the cell permeant calcein-acetoxymethyl ester. After 30 minutes the cells were placed into coverslip holders and washed with the NaCl-based medium containing 250 μM sulfinpyrazone, a multidrug transporter inhibitor, to minimize leakage of the dye. The basal fluorescence level was recorded for at least one minute before addition of transport solution (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM glucose, and 15 mM MES, pH 5.5) with or without 100 μM CoCl2 or 100 μM freshly prepared ferrous sulfate. To determine the kinetic parameters of the transporters, the same measurements were performed in solution containing either 3 μM, 10 μM, or 30 μM CoCl2. The pH dependence of Co++ transport was analyzed by modification of the pH of the transport solution from pH 5.5 to pH 6.5, both with 100 μM CoCl2. To facilitate comparison, the fluorescence was normalized by determination of the F0/F ratio (F0 corresponding to the basal fluorescence). At least 4 measurements with similar levels of basal fluorescence intensity were performed and used for comparison. Data storage and statistical analysis, including Student t tests, were performed using Graphpad Prism software (San Diego, CA).

Results

The G185R mutation impairs maturation of Nramp2

We generated cell lines stably expressing extracellularly HA-tagged isoform I of WT and Nramp2G185R. Earlier experiments had demonstrated that the introduction of this exofacial tag has no detectable effect on the subcellular distribution or transport function of the protein.20 Figure 1A illustrates representative immunoblots of LLC-PK1 cells probed with anti-HA Ab. Two bands of approximately 66 kDa and 93 kDa were discernible in WT cells, corresponding to the core- and complex-glycosylated forms of Nramp2.20 The same 2 species were observed in Nramp2G185R-transfected cells but, remarkably, the relative intensity of the bands was markedly different: the core-glycosylated form was much more abundant in the mutants, whereas the converse was true for the WT cells. This difference was not attributable to clonal differences, since a similar pattern was observed in several independent cell clones (Figure 1A-B). Moreover, the observation was not unique to LLC-PK1 cells, as similar differences in abundance of immunoreactive Nramp2 species were reproduced in CHO cells expressing Nramp2 WT or Nramp2G185R (Figure 1A). A summary of densitometric quantitation of several experiments is shown in Figure 1C. Treatment of the cells with the glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin revealed that the electrophoretic mobility of the nonglycosylated form of WT and Nramp2G185R was similar, corresponding to a molecular mass of 60 kDa (Figure 1B), and confirmed that the larger species described above are the result of glycosylation. These findings suggested that the G185R mutation alters the ability of Nramp2 to proceed from the core-glycosylated precursor to the fully glycosylated mature species.

Expression of WT and Nramp2G185R in stably transfected cells. (A) Lysates of LLC-PK1 cells (left) or CHO cells (right) stably transfected with either the WT or G185R forms of HA epitope–tagged Nramp2 were subjected to electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. Two separate clones of LLC-PK1 cells transfected with mutant Nramp2 are illustrated. The positions of the complex-glycosylated (▦) and core-glycosylated forms of Nramp2 (□) are indicated to the left and the locations of molecular weight markers are shown to the right. Immunoblot is representative of 4 experiments. (B) LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either the WT or G185R forms of Nramp2 were either left untreated (control) or were incubated with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin for 16 hours before solubilization, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting as for panel A. Representative of 4 experiments. (C) Quantification of the relative proportion of complex-glycosylated and core-glycosylated Nramp2 in LLC-PK1 cells transfected with WT or mutant Nramp2. Immunoblots from experiments like that in panel A were scanned and the optical density of the complex- and core-glycosylated forms were then expressed as a percentage of the total. Data are means plus or minus SE of 8 experiments.

Expression of WT and Nramp2G185R in stably transfected cells. (A) Lysates of LLC-PK1 cells (left) or CHO cells (right) stably transfected with either the WT or G185R forms of HA epitope–tagged Nramp2 were subjected to electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. Two separate clones of LLC-PK1 cells transfected with mutant Nramp2 are illustrated. The positions of the complex-glycosylated (▦) and core-glycosylated forms of Nramp2 (□) are indicated to the left and the locations of molecular weight markers are shown to the right. Immunoblot is representative of 4 experiments. (B) LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either the WT or G185R forms of Nramp2 were either left untreated (control) or were incubated with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin for 16 hours before solubilization, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting as for panel A. Representative of 4 experiments. (C) Quantification of the relative proportion of complex-glycosylated and core-glycosylated Nramp2 in LLC-PK1 cells transfected with WT or mutant Nramp2. Immunoblots from experiments like that in panel A were scanned and the optical density of the complex- and core-glycosylated forms were then expressed as a percentage of the total. Data are means plus or minus SE of 8 experiments.

Subcellular distribution of WT and mutant Nramp2

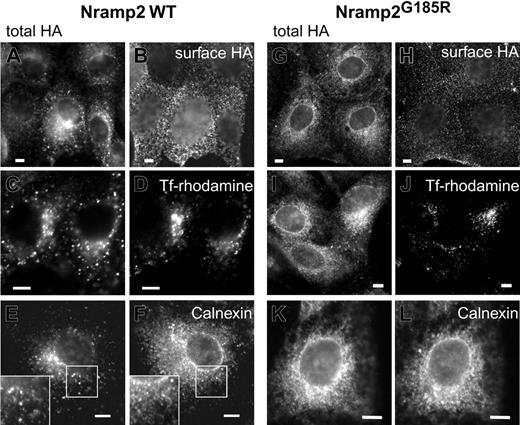

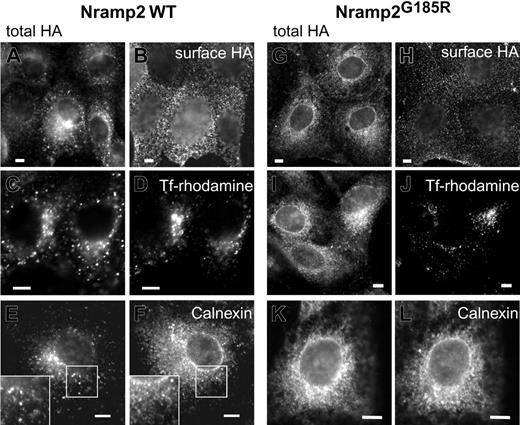

Proteins acquire complex glycosylation while traversing the Golgi complex en route to the plasma membrane. The observations described in Figure 1 suggested that the subcellular traffic and maturation of Nramp2G185R may be altered. We therefore analyzed the subcellular distribution of WT and Nramp2G185R in transfected cells by immunostaining (Figure 2). We took advantage of the exofacial HA epitope tag to unambiguously identify Nramp2 located at the plasmalemma, by incubating intact cells with anti-HAAb. The total cellular Nramp2 was revealed after permeabilization, re-adding primary Ab and using secondary Ab with a different fluorophore. As reported earlier,3,18,20 WT Nramp2 was found to be abundant on the plasmalemma (Figure 2B), but was also present in endomembranes (Figure 2A) where it colocalized extensively with transferrin receptors, indicative of early/recycling endosomes (Figure 2C-D). A modest fraction of WT Nramp2 was found to overlap with calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker (Figure 2E-F). Similar results were obtained using KDEL-GFP as the ER marker (not illustrated). The latter observation is consistent with the presence of a small fraction of core-glycosylated Nramp2 detected by immunoblotting (Figure 1).

Subcellular distribution of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT (A, C, E) or G185R (G, I, K) Nramp2-HA were immunostained with anti-HA antibodies following fixation and permeabilization, to reveal the total cellular Nramp2. The corresponding panels, B, D, F and H, J, L, were stained as follows: B and H, surface Nramp2 was stained selectively by treatment with anti-HA Ab prior to permeabilization, as described in “Materials and methods”; D and J, the cells were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated transferrin for 2 hours prior to fixation to label early endosomes; F and L, permeabilized cells were immunostained with anti-calnexin antibodies. Insets in E and F are magnifications of the indicated areas. Images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments of each type. Scale bars equal 5 μm.

Subcellular distribution of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT (A, C, E) or G185R (G, I, K) Nramp2-HA were immunostained with anti-HA antibodies following fixation and permeabilization, to reveal the total cellular Nramp2. The corresponding panels, B, D, F and H, J, L, were stained as follows: B and H, surface Nramp2 was stained selectively by treatment with anti-HA Ab prior to permeabilization, as described in “Materials and methods”; D and J, the cells were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated transferrin for 2 hours prior to fixation to label early endosomes; F and L, permeabilized cells were immunostained with anti-calnexin antibodies. Insets in E and F are magnifications of the indicated areas. Images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments of each type. Scale bars equal 5 μm.

Nramp2G185R was also detectable at the cell surface, but the fraction of plasmalemmal transporters was considerably smaller than in WT cells (Figure 2A-B,G-H). Similarly, only a small fraction of Nramp2G185R colocalized with transferrin receptors (Figure 2I-J). In contrast, most of the mutant Nramp2 was detected in the ER, overlapping extensively with calnexin (Figure 2K-L). Similar results were obtained using KDEL-containing proteins as markers of the ER (data not shown). These findings are in agreement with the observation that the core-glycosylated species is the predominant form of Nramp2G185R.

The ability of both the WT and, to a lesser extent, Nramp2G185R to reach the membrane was confirmed by an independent method. Intact cells were subjected to covalent biotinylation with an impermeant reagent. Biotinylated proteins were then isolated using immobilized avidin beads, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and finally analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. As illustrated in Figure 3, only the complex-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 can be biotinylated in intact cells, implying that it is exposed externally, while the core-glycosylated species resides intracellularly, likely in the ER, remaining inaccessible to the membrane-impermeant biotin reagent. A fraction of the G185R mutant also became biotinylated, confirming that it reaches the plasmalemma. Most of the labeled mutant was complex-glycosylated, yet a small fraction of the core-glycosylated form also became biotinylated. This may imply that complex glycosylation of the Nramp2G185R mutant is not essential to reach the surface membrane, but it is simpler to assume that the minute fraction of biotinylated 66 kDa species reflects the presence of a small number of nonviable cells in the culture.

Detection of exofacial Nramp2 by biotinylation. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were treated with EZ-NHS-sulfoBiotin, a membrane-impermeant biotinylating reagent, as described in “Materials and methods.” Cell lysates were prepared and biotinylated membrane proteins were precipitated using mono-avidin beads. The biotinylated proteins were eluted, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE together with samples of the initial whole-cell lysate, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and blotted with anti-HA antibodies to identify Nramp2. The volume of whole-cell lysate (labeled “Total extract” in the figure) was equivalent to one tenth of the amount used for avidin precipitation in the corresponding lanes labeled “Biotinylated.” The blot is representative of 3 experiments.

Detection of exofacial Nramp2 by biotinylation. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were treated with EZ-NHS-sulfoBiotin, a membrane-impermeant biotinylating reagent, as described in “Materials and methods.” Cell lysates were prepared and biotinylated membrane proteins were precipitated using mono-avidin beads. The biotinylated proteins were eluted, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE together with samples of the initial whole-cell lysate, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and blotted with anti-HA antibodies to identify Nramp2. The volume of whole-cell lysate (labeled “Total extract” in the figure) was equivalent to one tenth of the amount used for avidin precipitation in the corresponding lanes labeled “Biotinylated.” The blot is representative of 3 experiments.

Reduced stability and folding efficiency of Nramp2G185R

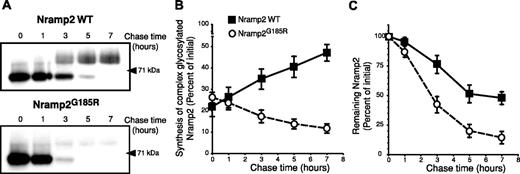

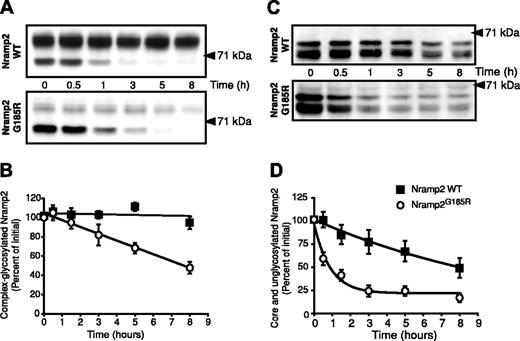

The preceding experiments suggested that the G185R mutation alters the ability of Nramp2 to mature along the biosynthetic pathway. However, neither the rate of maturation nor the maturation efficiency of Nramp2 has been determined. We used a metabolic pulse-chase protocol to analyze these parameters in WT and Nramp2G185R. As illustrated in the top panel of Figure 4A, the core-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 (∼ 66 kDa) is rapidly converted to the mature species (∼ 93 kDa), which becomes apparent after 3 hours. The maturation efficiency, calculated as the ratio of complex-glycosylated protein formed divided by the amount of core-glycosylated form synthesized during the pulse, is comparatively low (≤ 50%); this value is likely an overestimate, as it was difficult to resolve entirely the mature species from the trailing edge of the core-glycosylated form. This accounts for the artifactually elevated value of complex-glycosylated species at zero time in Figure 4B, where the maturation kinetics of 4 similar experiments is collated.

Estimation of the rates of formation and degradation of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were labeled metabolically by a 60-minute pulse of 35S-Met/Cys, followed by chase periods of the indicated length (in hours). The cells were next subjected to lysis, immunoprecipitation of Nramp2, gel electrophoresis, and autoradiography. (A) Typical radiograms of WT Nramp2 (top) and Nramp2G185R (bottom) transfected cells. (B) Estimation of the rate and efficiency of formation of the complex-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○). (C) Estimation of the rate of disappearance of the core-glycosylated species. Data in B and C were quantified as described in “Materials and methods” and are means plus or minus SE of 4 separate experiments.

Estimation of the rates of formation and degradation of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were labeled metabolically by a 60-minute pulse of 35S-Met/Cys, followed by chase periods of the indicated length (in hours). The cells were next subjected to lysis, immunoprecipitation of Nramp2, gel electrophoresis, and autoradiography. (A) Typical radiograms of WT Nramp2 (top) and Nramp2G185R (bottom) transfected cells. (B) Estimation of the rate and efficiency of formation of the complex-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○). (C) Estimation of the rate of disappearance of the core-glycosylated species. Data in B and C were quantified as described in “Materials and methods” and are means plus or minus SE of 4 separate experiments.

Similar pulse-chase studies of Nramp2G185R revealed a strikingly different behavior. Despite the fact that the amount of Nramp2G185R core-glycosylated precursor was greater than that of WT protein expressed in the same cells, only a minute fraction was processed to the mature, complex-glycosylated state (Figure 4A, bottom panel). The concomitant disappearance of the trailing edge of the precursor made it impossible to quantify the efficiency of maturation (Figure 4B, open circles). Despite this limitation, it is obvious that the maturation efficiency of the Nramp2G185R mutant is minute and much lower than that of WT Nramp2.

Pulse-chase experiments like those in Figure 4A also enabled us to estimate the stability of Nramp2. As shown in Figure 4A,C, the mutant core-glycosylated form is degraded rapidly, with a half-life of 2 to 3 hours. The disappearance of the WT core-glycosylated species is slower and is only partially due to degradation, since a significant fraction is converted to the mature form. Thus, the core-glycosylated form of Nramp2G185R exits the ER inefficiently and is rapidly degraded therein.

Although small, the fraction of Nramp2G185R reaching the plasma membrane is not negligible, as indicated by the steady-state presence of a small fraction of complex-glycosylated mutant (Figure 1) and by its accessibility to impermeant reagents (Figures 2 and 3). It was therefore of interest to determine if the half-life of the mature form is comparable to that of the corresponding WT species, or whether the mutation also affects its stability. WT- and Nramp2G185R-expressing cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide and the rate of disappearance of Nramp2 was estimated by immunoblotting. As illustrated in Figure 5, the mature form of WT Nramp2 (∼ 93 kDa) is extremely stable, decreasing only negligibly during the course of 8 hours. By contrast, the amount of mature Nramp2G185R decreases by over 50% during the same period, despite the presence of a larger pool of core-glycosylated protein (∼ 66 kDa). Calculation of the slopes of the 2 lines in Figure 5B confirms that the mature form of the Nramp2G185R is degraded 20 times faster than the WT.

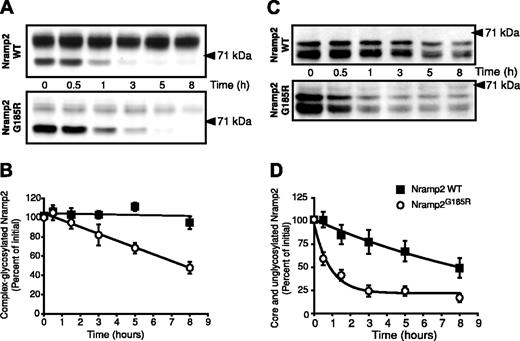

Determination of the half-life of the different glycosylation states of WT and Nramp2G185R. (A) LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT (top) or Nramp2G185R-HA (bottom) were treated with cycloheximide (20 μg/mL) for the indicated periods of time. Whole-cell lysates were then subjected to electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (B) Rate of disappearance of the complex-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○), from 4 experiments like that in panel A. (C) Cells were incubated overnight with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin before addition of cycloheximide. Analysis was done as for panel A. (D) Rate of disappearance of the core- and unglycosylated forms of WT Nramp2 and Nramp2G185R, from 4 experiments like that in panel C. Data in B and D are means plus or minus SE.

Determination of the half-life of the different glycosylation states of WT and Nramp2G185R. (A) LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with either WT (top) or Nramp2G185R-HA (bottom) were treated with cycloheximide (20 μg/mL) for the indicated periods of time. Whole-cell lysates were then subjected to electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (B) Rate of disappearance of the complex-glycosylated form of WT Nramp2 (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○), from 4 experiments like that in panel A. (C) Cells were incubated overnight with 2.5 μg/mL tunicamycin before addition of cycloheximide. Analysis was done as for panel A. (D) Rate of disappearance of the core- and unglycosylated forms of WT Nramp2 and Nramp2G185R, from 4 experiments like that in panel C. Data in B and D are means plus or minus SE.

Disappearance of the core-glycosylated species in experiments like that in Figure 5A could be due to conversion to the mature species, but can also reflect degradation within the ER. To better estimate the stability of the protein independently of its glycosylation, WT- and Nramp2G185R-expressing cells were treated with the glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin prior to addition of cycloheximide. Typical results are shown in Figure 5C. In agreement with results in Figure 1B, treatment with tunicamycin results in accumulation of the nonglycosylated form of Nramp2 (∼ 60 kDa) for both the WT and mutant Nramp2, with a small amount of the core-glycosylated species (∼ 66 kDa) detected. The sum of these 2 species decreases from WT cells with a half-life of about 8 hours (Figure 5D), confirming the notion that even the native protein becomes degraded to a significant extent in the ER. However, the rate of disappearance of the Nramp2G185R was much greater, with a half-life of approximately one hour (Figure 5D), of the same order as found in the pulse-chase experiments (Figure 4). Jointly, these experiments indicate that both the mature and immature forms of Nramp2G185R are considerably less stable than their WT counter-parts. Moreover, the data obtained in the presence of tunicamycin imply that failure to become properly glycosylated is a consequence and not the cause of the retention and fast degradation of Nramp2G185R in the ER.

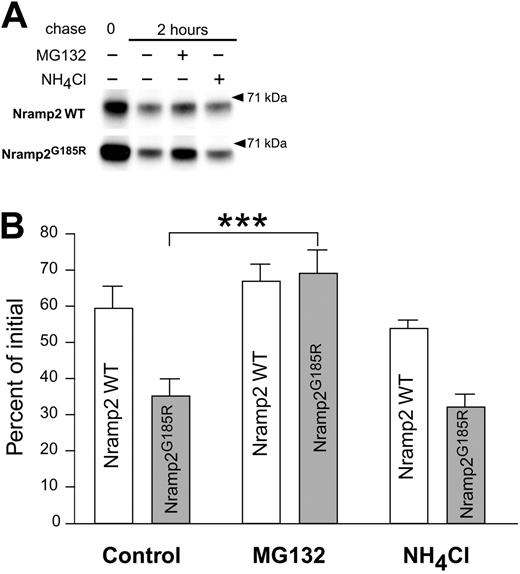

Role of lysosomes and proteasomes in Nramp2 degradation

The mechanism responsible for the rapid degradation of Nramp2G185R was investigated. The cells were pulsed for one hour with radiolabeled amino acids, followed by a 2-hour chase in the presence and absence of inhibitors of lysosome- or proteasome-mediated degradation (Figure 6). Treatment with

Analysis of the degradation mechanisms of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were labeled metabolically by a one-hour pulse of 35S-Met/Cys. Samples of the labeled cells were taken immediately after the pulse (0 chase) or after a 2-hour chase in the absence of presence of either 10 μM of MG132 or 15 mM of NH4Cl, as indicated. The cells were next subjected to lysis, immunoprecipitation of Nramp2, gel electrophoresis, and autoradiography, as in Figure 4. (A) Typical radiograms of WT (top) and Nramp2G185R (bottom) transfected cells. Only the band corresponding to the core-glycosylated species is shown. (B) Quantification of the fraction of core-glycosylated Nramp2 remaining after a 2-hour chase, normalized to the amount of the respective protein immediately after the radioactive pulse. Data are means plus or minus SE of 3 experiments like that shown in panel A. ***P < .001, calculated using Student t test.

Analysis of the degradation mechanisms of WT and Nramp2G185R. LLC-PK1 cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R-HA were labeled metabolically by a one-hour pulse of 35S-Met/Cys. Samples of the labeled cells were taken immediately after the pulse (0 chase) or after a 2-hour chase in the absence of presence of either 10 μM of MG132 or 15 mM of NH4Cl, as indicated. The cells were next subjected to lysis, immunoprecipitation of Nramp2, gel electrophoresis, and autoradiography, as in Figure 4. (A) Typical radiograms of WT (top) and Nramp2G185R (bottom) transfected cells. Only the band corresponding to the core-glycosylated species is shown. (B) Quantification of the fraction of core-glycosylated Nramp2 remaining after a 2-hour chase, normalized to the amount of the respective protein immediately after the radioactive pulse. Data are means plus or minus SE of 3 experiments like that shown in panel A. ***P < .001, calculated using Student t test.

Is Nramp2G185R functional at the plasma membrane?

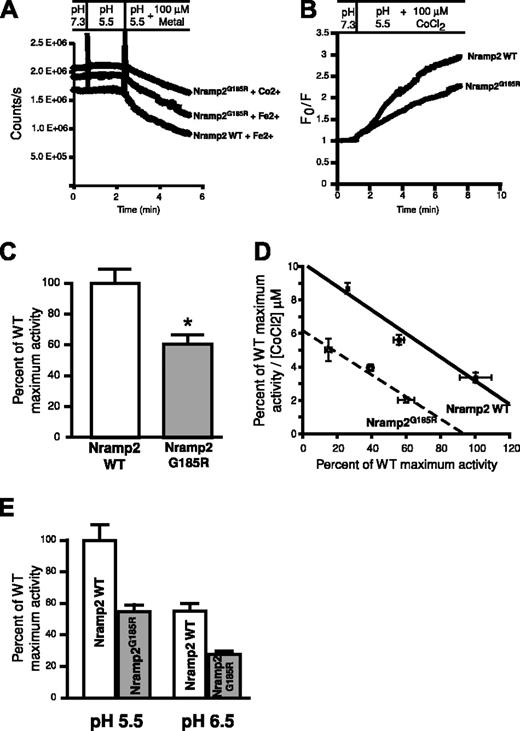

Although less abundant than the WT protein, Nramp2G185R is nevertheless present at the plasma membrane of transfected LLC-PK1 cells (Figures 2 and 3). Previous transport studies in transiently transfected HEK293 cells expressing Nramp2G185R suggested that the protein was functionally inactive.18 However, the fraction of the protein present at the plasma membrane was not established in these studies, raising the possibility that mistargeting, in addition to functional impairment, may have been responsible for reduced transport. To eliminate this ambiguity we quantified the number of plasmalemmal Nramp2 in the same cells used for transport studies, and normalized the rates of uptake per unit of Nramp2 present at the surface. The density of surface transporters was established using antibodies to the exofacial epitope tag, followed by peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies and colorimetric quantitation of bound peroxidase activity. Transport was assessed in intact cells loaded with the divalent cation-sensitive probe calcein, and measured as the rate of calcein quenching upon uptake of iron or cobalt. The extent of calcein loading was indistinguishable between cells expressing WT or mutant Nramp2. As illustrated in Figure 7A, both the WT and mutant forms of Nramp2 supported uptake of iron, as indicated by the gradual fluorescence decrease noted upon addition of the metal. Transport of cobalt was of similar magnitude (Figure 7A) and this cation was used hereafter for convenience, since it is less susceptible to redox changes than iron. Additional validation for the use of cobalt as an iron surrogate has been presented earlier for both Nramp2 WT2,4,5 and for Nramp2G185R.21 Representative experiments where the flux has been normalized to facilitate comparison are shown in Figure 7B and the summary of 6 determinations is presented in Figure 7C. As concluded by Su et al,18 metal transport by Nramp2G185R is significantly reduced compared with WT, though the specific transport activity of the mutant assessed using cobalt was nevertheless considerable (≈ 60% of the WT activity).

Comparative assessment of the transport properties of WT and Nramp2G185R. (A) Measurements of calcein fluorescence in cells expressing WT Nramp2 or Nramp2G185R. Cells were initially bathed at pH 7.3 and pH was lowered to 5.5 where indicated. Finally, 100 μMCo2+ or Fe2+ was added as noted. Representative raw data are illustrated. (B) Co2+ uptake determinations by cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R, calculated from experiments like that in panel A. Data are presented as the ratio of the initial fluorescence (F0) divided by the fluorescence (F) recorded at the indicated times. (C) The initial rates of Co2+ transport, measured as in panel B, were normalized by the number of surface-exposed Nramp2 molecules, determined in parallel with anti-HA antibodies, as described in “Materials and methods.” To facilitate comparison, the specific transport activity of the mutants is expressed as a fraction of the WT. Data are means plus or minus SE of 6 individual determinations. *P < .05, determined by Student t test. (D) Eadie-Hofstee plot of the transport activity of WT (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○) as a function of the concentration of Co2+. Data are means plus or minus SE of 6 determinations. (E) pH dependence of Co2+ transport in cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R. Measurements of the specific transport activity are presented as a fraction of the activity of WT Nramp2 at pH 5.5. Data are means plus or minus SE of 4 determinations.

Comparative assessment of the transport properties of WT and Nramp2G185R. (A) Measurements of calcein fluorescence in cells expressing WT Nramp2 or Nramp2G185R. Cells were initially bathed at pH 7.3 and pH was lowered to 5.5 where indicated. Finally, 100 μMCo2+ or Fe2+ was added as noted. Representative raw data are illustrated. (B) Co2+ uptake determinations by cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R, calculated from experiments like that in panel A. Data are presented as the ratio of the initial fluorescence (F0) divided by the fluorescence (F) recorded at the indicated times. (C) The initial rates of Co2+ transport, measured as in panel B, were normalized by the number of surface-exposed Nramp2 molecules, determined in parallel with anti-HA antibodies, as described in “Materials and methods.” To facilitate comparison, the specific transport activity of the mutants is expressed as a fraction of the WT. Data are means plus or minus SE of 6 individual determinations. *P < .05, determined by Student t test. (D) Eadie-Hofstee plot of the transport activity of WT (▪) and Nramp2G185R (○) as a function of the concentration of Co2+. Data are means plus or minus SE of 6 determinations. (E) pH dependence of Co2+ transport in cells transfected with WT or Nramp2G185R. Measurements of the specific transport activity are presented as a fraction of the activity of WT Nramp2 at pH 5.5. Data are means plus or minus SE of 4 determinations.

The reduced transport activity of the mutant was not attributable to a change in the affinity for its substrate. Analysis of the concentration dependence of the rate of cobalt transport revealed that the apparent Km was similar in WT and Nramp2G185R (14.3 μM and 15.3 μM, respectively). Instead, the maximal velocity of transport was found to be reduced by 35% in the mutant (Figure 7D). The reduction in maximal activity is not likely due to altered sensitivity to extracellular H+, since the relative inhibition of transport was similar when the experiments were performed in media of pH 5.5 and pH 6.5 (Figure 7E). It is therefore most likely that the conformational changes associated with the mutation reduce the ability of the transporters to traverse the membrane, rather than the affinity for their ligands.

Discussion

Uptake of iron by intestinal epithelial cells via Nramp2 appears to be crucial for the systemic homeostasis of the metal. Similarly, Nramp2 plays a critical role in cellular iron regulation by mediating the delivery to the cytosol of iron carried into the endosomes by transferrin. The functional importance of Nramp2 is underscored by the severity of the phenotype reported in animals where the metal transporter is impaired. Both Belgrade rats and mk mice have much-reduced rates of systemic and cellular iron absorption and are afflicted by hypochromic microcytic anemia10-12,14 that cannot be rescued by supplemental iron, whether introduced by the oral or intravenous route.

In this report we found that not one, but multiple aspects of the function of Nramp2 are altered by the G185R mutation. First, the folding efficiency of the mutant protein is greatly reduced. The inability of the protein to acquire the optimal configuration markedly decreases the rate at which it can exit the endoplasmic reticulum to undergo carbohydrate remodeling in the Golgi complex and ultimately insertion into the surface and endosomal membranes. Second, retention of Nramp2G185R in the reticulum, coupled with its improperly folded configuration, accelerates the degradation of the mutant, compared with its WT counterpart. As found for other membrane proteins,22,23 degradation of misfolded forms occurs primarily via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, presumably following retrotranslocation of the proteins targeted for destruction. Although poorly folded, Nramp2G185R is nevertheless capable of reaching the cell surface, an occurrence that is detectable both biochemically and by ion transport determinations. Yet, the plasmalemmal mutant is subjected to additional challenges. Pulse-chase experiments demonstrated that the residence time of Nramp2G185R in the combined compartment composed of the surface and recycling endosomal membranes is considerably shorter than that of WT Nramp2. Last, although present at the surface and endosomal membrane, Nramp2G185R is not as efficient in the transport of metals as is the WT protein. Defective transport was confirmed even when the density of carriers at the membrane was normalized to account for the improper delivery and reduced stability of the mutants. Thus, the biosynthetic and stability defects of Nramp2G185R are compounded by its impaired ability to translocate metals, resulting in a drastic depression in iron uptake.

The finding that Nramp2G185R is present in the apical membrane of stably transfected LLC-PK1 cells appears to be at odds with our earlier report that the protein was not detectable by immunocyto-chemical means in the brush borders of epithelia in mice bearing the mutation.19 However, it must be borne in mind that a strong, exogenous promoter was used for the generation of the transfected cell lines, leading to levels of constitutive transcription that are in all likelihood higher than those of the primary tissues. Moreover, of the multiple clones generated, those with higher expression levels were chosen for these studies, to facilitate detection. These factors, together with the differential ability of the antibodies used in the 2 studies, can readily account for the apparent discrepancy. In view of these considerations, we feel that in animals bearing the G185R mutation the level of endogenous Nramp2 expression at the cell surface is very low and that the paucity of transporters is the predominant cause of impaired iron uptake. The reduced catalytic activity of the protein is likely to be a minor contributor to the transport defect. Indeed, the 35% decrease in intrinsic activity of Nramp2G185R appears too modest to explain the severe iron deficiency reported in mk and b animals. It is noteworthy that our measurements used cobalt as an iron surrogate, but all previous studies indicate that the differences in the behavior of the WT and mutant Nramp2 are manifested comparably when using either cation.2,4,5,21

It is noteworthy that the mk and b mutation in Nramp2 and the Bcg/Ity/Lsh mutation in Nramp1 are found at adjacent, conserved residues within the equivalent (fourth) predicted transmembrane domain of the respective proteins. When the 2 proteins are aligned based on their primary sequence homology, the Bcg/Ity/Lsh mutation of Nramp1 (G169D) corresponds to position 184 in Nramp2, immediately upstream of the site where the mk and b mutation is found (G185R). It is therefore very likely that both mutations will cause similar structural alterations of the fourth transmembrane domain and consequent destabilization of the protein. We would therefore anticipate that, like Nramp2G185R, Nramp1G169D will experience difficulty exiting the biosynthetic compartment and will have reduced stability and lower activity in late endosomes and lysosomes, its target destinations, if it reaches these compartments at all. These notions remain to be validated experimentally, but are consistent with (1) the observed loss of transport in Nramp2 protein bearing the Bcg/Ity/Lsh mutation (Nramp2G184D),21 and (2) the absence of mature Nramp1G169D protein reported in peritoneal macrophages from infection-susceptible inbred strains.24

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 20, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0731.

Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Arthritis Society, and the National Sanatorium Association. N.M.-O. is the recipient of a RESTRACOMP Fellowship from the Hospital for Sick Children. S.G. is the current holder of the Pitblado Chair in Cell Biology and is cross-appointed to the Department of Biochemistry, University of Toronto.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.