Abstract

Bleeding into the joints is common in patients with hemophilia. After total knee or elbow replacement, profuse intraarticular bleeding unresponsive to high-dose clotting factor replacement sometimes occurs. In some patients who have severely damaged elbow or knee joints the same profuse bleeding pattern can be seen. To control bleeding in these patients, selective catheterization with a microcatheter and therapeutic embolization with microcoils was performed whenever a severe blush or microaneurysm was observed on angiography. Over 12 years, in 23 cases of massive joint bleeding in 18 patients with hemophilia selective catheterization was performed. In 15 cases the bleeding was postoperative and in 8 spontaneous. Results of angiographic imaging revealed vascular blush, false aneurysm, true aneurysm, and arteriovenous shunt in combination with an aneurysm as cause of bleeding. In 2 patients, the cause of bleeding was not found. In 21 cases an embolization procedure was performed, in which the bleeding was completely controlled by a single procedure in 14 cases. Recurrence of the bleeding occurred in 7 cases and required a second embolization procedure; in one patient even a third embolization was required to stop the bleeding completely. No difference in the outcome, that is, clinical end of bleeding and joint range of motion, was observed, when comparing postoperative and spontaneous bleeding.

Introduction

Bleeding into the joints, particularly the elbow, knee, and ankle, is common in individuals with hemophilia.1 Repeated episodes may result in cartilage damage and synovial changes leading to severe arthropathy.2-4 Some patients have specific target joints, in which they have a higher bleeding frequency. These bleeding episodes are usually successfully treated with replacement of factor VIII or IX by injection of clotting factor concentrates. Long-term prophylaxis can prevent these episodes of joint bleeding and consequent arthropathy.5,6 Older patients with severe hemophilia, as well as hemophilia patients with antibodies developed against factor VIII or IX (inhibitors) often do not receive adequate prophylaxis. In these patients, recurrent hemarthroses have resulted in severe joint damage, for which joint replacement is often necessary. After total knee or elbow replacement, profuse bleeding sometimes occurs into the joint. These episodes of bleeding show a characteristic rapid onset of the bleeding, resulting in a complete loss of function, intense pain, and considerable swelling of the joint, all developing within 1 hour. Such episodes of bleeding can hardly be prevented by prophylaxis and often are unresponsive to intensive high-dose clotting factor replacement therapy. In some patients with end-stage hemophilic arthropathy7 of elbow and knee joints, the same bleeding pattern can occur without previous joint replacement and even despite adequate (secondary) prophylaxis.

Because this kind of bleeding does not respond to the standard therapeutic measures such as clotting factor replacement therapy, immobilization, and cold packs, we explored an alternative therapy. Because in this type of hemorrhage an acute massive amount of bleeding occurs, we thought it might specifically be caused by arterial abnormalities rather than the usual synovial bleeding, and that local interventional therapy might be an option. Therefore, we performed angiography in all patients with this pattern of bleeding into their knee or elbow, when intensive replacement therapy was ineffective. Since 1992, angiography with embolization has been performed in patients with postoperative massive bleeding in the knee and elbow.8 In 2000, we started performing angiographic embolization in patients with profuse spontaneous elbow and knee bleeding, whether or not they had just undergone a surgical procedure. We now describe the results of our experience with angiographic embolization in these patients.

Patients, materials, and methods

Population

Patients with severe hemophilia A or B with or without inhibitors who suffered from profuse persistent bleeding unresponsive to high-dose clotting factor substitution were eligible for embolization. Two groups of patients could be distinguished. Group 1 included patients in whom bleeding occurred within the 6-month period after joint replacement. Group 2 patients were those with end-stage hemophilic arthropathy, without previous arthroplasty, with an acute profuse bleeding that caused severe pain and total loss of function. The authors received permission from all patients to collect data anonymously. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Angiographic procedure and embolization

After correction of clotting factor levels, a digital substraction angiogram was performed. When bleeding occurred in the knee, an ipsilateral antegrade puncture was done and a 5-French (FR) sheath was introduced. With a cobra-shaped catheter, the popliteal artery and supragenual and infragenual arteries were selectively catheterized and an angiograph obtained. Whenever an excessive blush (hyperemic tissue) or a ruptured microaneurysm was found, a microcatheter was advanced and embolization was performed with microcoils. Afterward a repeat angiographic picture of the popliteal artery was obtained to assess the outcome.

When the elbow was the bleeding site, a retrograde puncture was done in the common femoral artery. Next a headhunter-shaped catheter was used to catheterize the left or right subclavian artery and to obtain an overview of the arterial pattern in the region of the elbow. Selective catheterization with a microcatheter and therapeutic embolization with microcoils was performed whenever a severe blush or microaneurysm was observed. Afterward, a repeat angiographic visualization was performed.

Definition of clinical success

Clinical success was defined as complete cessation of bleeding following embolization. This was accompanied by a decrease in pain and swelling and an improvement in range of motion within 24 hours after catheterization, which was sustained in subsequent days after the patient's circulating level of clotting factor decreased to the low steady-state level.

Follow-up

Clinical effects were evaluated after 24 hours and within 1 week following the procedure. Thereafter, patients were seen at least every 3 months during the first year and every 6 months during the following years. If recurrent bleeding episodes occurred, patients were seen more often.

Results

Clinical outcomes

Since 1992, catheterization was performed in 23 patients with acute profuse bleeding in the knee or elbow. Twenty patients had hemophilia A and 3 had hemophilia B (2 inhibitors). The median age at time of angiography was 47 years (range, 14-67 years); the median follow-up after angiography was 48 months (range, 9-134 months). In 15 patients postoperative bleeding initially occurred within 6 months after knee (n = 14) or elbow (n = 1) replacement. In 8 additional patients, spontaneous bleeding into the elbow (n=7) or knee (n = 1) was the indication for angiography. In 8 cases a second or third catheterization was performed.

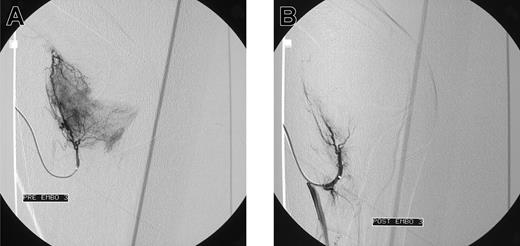

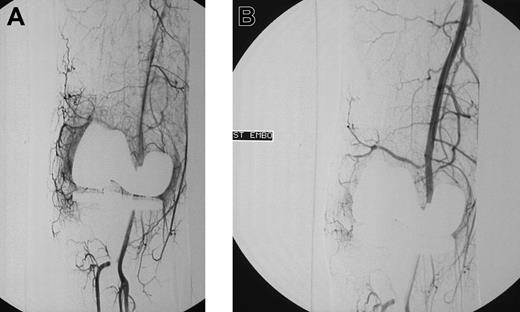

Initial angiograms demonstrated a blush, indicative for hyperemic tissue as cause of bleeding in 15 patients (Figure 1A-B); in 2 patients a false aneurysm was observed (Figure 2A-B); in one patient a true aneurysm was observed; and in 3 patients an arteriovenous shunt in combination with an aneurysm was observed. In all these cases embolization of the feeding arteries was performed. However, in some cases, it was not possible to embolize all the bleeding arteries. In 2 patients, the cause of bleeding could not be localized (one patients with postoperative knee bleeding and one with spontaneous elbow bleeding) and embolization was not performed.

Blush in a patient with elbow bleeding. Angiogram shows massive blush in a patient with recurrent spontaneous elbow bleeding before (A) and after (B) embolization.

Blush in a patient with elbow bleeding. Angiogram shows massive blush in a patient with recurrent spontaneous elbow bleeding before (A) and after (B) embolization.

Blush in a patient with knee bleeding. Angiogram shows blush in a patient with recurrent massive knee bleeding following joint replacement before (A) and after (B) embolization.

Blush in a patient with knee bleeding. Angiogram shows blush in a patient with recurrent massive knee bleeding following joint replacement before (A) and after (B) embolization.

Embolization was initially effective in 20 patients. In these patients the bleeding stopped and no profuse bleeding was observed at repeat angiography. In one patient repeat angiography demonstrated only a partial occlusion of the bleeding artery following the embolization procedure. However, the clinical result was satisfactory.

Rebleeding occurred in 7 patients, 6 postoperative and 1 spontaneous bleeding (Table 1). In all 7, a second angiography was done and demonstrated the affected artery. In all cases embolization was performed. Repeat embolization resulted in a complete control of bleeding in 5 patients. In 2 patients, a decrease of bleeding was seen, which could subsequently be controlled effectively with standard conservative therapy with clotting factor concentrates. In one of these patients even a second recurrence of bleeding occurred; this was once again successfully treated with embolization during a third angiography.

Complications

In 6 of 31 angiographic procedures one or more complications were observed. Three patients complained of pain in the affected joint during or shortly after the procedure. One patient had a temporary spasm of the artery, and one patient had a small thrombus of the anterior tibial artery, for which heparin was locally injected during angiography. This resulted in good resolution of the thrombus and return of arterial pulsation. In a patient with hemophilia B and an inhibitor treated for repeated excessive right elbow bleeds, a severe psoas bleeding occurred 3 days after the procedure. The femoral puncture site was the origin of this bleeding complication; the bleeding was probably caused by early mobilization. The patient recovered completely, and for the subsequent 8 months he had no bleeding episodes into his right elbow. Later in the same patient, a second catheterization for a repeat episode of bleeding into his left elbow resulted in prolonged bleeding at the puncture site, which could easily be controlled.

Discussion

Replacement therapy with clotting factor concentrate is the therapy of choice in the treatment of bleeding episodes in hemophilia. In most cases this therapy is effective. However, bleeding episodes in severely damaged joints, or after implantation of prostheses, are occasionally unresponsive to clotting factor replacement therapy.

Until now, embolization used as principal therapy for joint bleedings in patients with hemophilia has rarely been performed. We could only find one report on therapeutic embolization in patients with hemophilia.9 Even more, there are only a few reports on therapeutic embolization for postoperative bleeding after total arthroplasty of knee or hip joints in patients without hemophilia.10,11 However embolization for other medical indications is not uncommon. For many years this procedure has been used successfully in treating patients without hemophilia, for ruptured intracranial aneurysms, obstetric hemorrhages, massive hemoptysis, or other types of massive bleeding and preoperatively in patients with well-vascularized tumors.12-15

We found that selective catheterization with placement of embolization coils is also an effective method to stop excessive bleeding in severely damaged hemophilic joints unresponsive to intensive clotting factor therapy. These bleeding episodes spontaneously occurred in patients who underwent arthroplastic surgery and who did not have arterial abnormalities on preoperative angiograms, as well as in patients who had not undergone surgery. No difference in bleeding pattern or effect of embolization was observed between those treated postoperatively and those treated for spontaneous bleeding episodes. Embolization often prevented recurrent bleeding in the same joint postoperatively. However, if massive rebleeding did occur, a second embolization procedure was always initially effective in stopping it, although in one patient a second rebleeding occurred. Successful embolization in hemophilia saves costs. Our patients had often been treated with high doses of clotting factor concentrates, more than 700 U/kg body weight for 1 week or for several months, with little or no success. Once successful control of joint bleeding was obtained with replacement therapy, recurrent bleeding was not uncommon. In our study, bleeding stopped immediately after embolization and further use of high doses of replacement clotting factor concentrates was unnecessary. This procedure improved the quality of life of the patients because they no longer suffered from painful disabling bleedings into their target joints, responding poorly to clotting factor therapy. Embolization was successful not only in patients in whom a false aneurysm occurred, but also in those in whom a blush of small arteries, probably indicating some minor extravascular leakage was causing the bleeding phenomenon.

In addition to our own experience only Mann et al9 reported successful embolization of a pseudoaneurysm in a hemophilia patient with a massive bleeding following total knee replacement. They suggest that selective digital subtraction angiography of the popliteal artery should be considered preoperatively in patients with hemophilia. However, when we did perform preoperative angiograms on our patients, who had had massive bleeding following knee replacement, we could find no abnormalities. A false aneurysm of an intra-articular artery might form subsequent to trauma-related surgery, as a result of disruption of the vessel wall. In our series a vascular blush without an aneurysm was the major cause of bleeding. In addition, false aneurysms occurred in patients with spontaneous bleeding episodes without previous surgery, and in one patient with a recurrent bleeding following embolization. In this patient, the angiogram performed for the initial bleeding demonstrated a blush only. Obviously, the false aneurysm had developed spontaneously afterward. Furthermore, only 4 cases of aneurysm have been reported in patients without hemophilia following surgical procedures of the knee, so this complication must be very exceptional.16-19

A limitation of the broader use of embolization procedures is that this method is technically demanding and can only be done by highly skilled radiologists. By bringing this effective treatment modality to the attention of the many specialist groups who care for such patients, its broader application may be possible.

In conclusion, angiographic embolization is an effective, successful, safe, and potentially cost-saving therapeutic intervention in hemophilia patients with massive knee and elbow bleedings unresponsive to appropriate and adequate clotting factor replacement.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 21, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2063.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The authors would like to thank Doctor Arja de Goede-Bolder from the Sophia Children's Hospital, Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam, The Netherlands, for providing us the additional data of 2 bleeding episodes in a patient with hemophilia B and an inhibitor.