Abstract

Rho GTPases control many facets of cell polarity and migration; namely, the reorganization of the cellular cytoskeleton to extracellular stimuli. Rho GTPases are activated by GTP exchange factors (GEFs), which induce guanosine diphosphate (GDP) release and the stabilization of the nucleotide-free state. Thus, the role of GEFs in the regulation of the cellular response to extracellular cues during cell migration is a critical step of this process. In this report, we have analyzed the activation and subcellular localization of the hematopoietic GEF Vav in human peripheral blood lymphocytes stimulated with the chemokine stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1α). We show a robust activation of Vav and its redistribution to motility-associated subcellular structures, and we provide biochemical evidence of the recruitment of Vav to the membrane of SDF-1α–activated human lymphocytes, where it transiently interacts with the SDF-1α receptor CXCR4. Overexpression of a dominant negative form of Vav abolished lymphocyte polarization, actin polymerization, and migration. SDF-1α–mediated cell polarization and migration also were impaired by overexpression of an active, oncogenic Vav, although the mechanism appears to be different. Together, our data postulate a pivotal role for Vav in the transmission of the migratory signal through the chemokine receptor CXCR4.

Introduction

Leukocyte migration in and out of target tissues during homeostasis and inflammation is a finely regulated process mediated by many receptors, which regulate rolling, adhesion and/or detachment, and motility. Chemotactic receptors play an important role in the modulation of cell adhesion as well as in controlling the morphology of migrating leukocytes.1 In particular, chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that, acting through heterotrimeric G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), regulate cell adhesion through cross-talk with integrin receptors and also modulate the morphology of migrating leukocytes.1,2

The chemokine stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1α) is the most pleiotropic of chemokines, being involved in many processes, from migration of hematopoietic progenitors and most leukocytes to morphogenesis in mammals and lower organisms such as zebrafish.3,4 SDF-1α interacts exclusively with the chemokine receptor CXCR4, the specificity of this pair being underscored by the similar phenotype of mice deficient for SDF-1α or CXCR4.5-7 SDF-1α has been shown to modulate adhesion through the integrins very late activation antigen-4 (VLA-4, α4β1) and leukocyte function associated antigen-1 (LFA-1, αLβ2),8 although the intracellular mechanisms involved in such cross-talk are largely undefined. We and others have shown that SDF-1α induces profound morphological changes in adherent leukocytes and the acquisition of a bipolar shape with a front leading edge, in which chemokine receptors are clustered,9-12 and a trailing edge or uropod that accumulates adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, -3, or CD44 (Vicente-Manzanares and Sanchez-Madrid1 ). CXCR4 triggering by SDF-1α induces the activation of numerous signaling pathways, including Ras/ERK,13 the JAK/STAT pathway,14 and PI3K-IA and -IB.15,16 Moreover, SDF-1α induces actin polymerization in a Rac- and Cdc42-dependent fashion17 and activates the small GTPase RhoA.18

Small GTPases are devices controlling the actin cytoskeleton (Etienne-Manneville and Hall19 ). The function of the 3 “classic” GTPases—Cdc42, Rac, and Rho—was determined in the mid-1990s, showing that different aspects of cell migration, such as filopodia extension (Cdc42), lamellipodia formation (Rac), and cell retraction and adhesion (Rho), are operated by these molecules.20-22 Small GTPases are thus at the core of actin regulation in migrating cells. However, the mechanisms by which SDF-1α triggers GTPase activation are largely unclear. Some reports have demonstrated that SDF-1α induces ZAP-70 activation,23,24 which is an upstream activator of Vav. Vav belongs to the Dbl family of GTP exchange factors (GEF), which favor GTP exchange for GDP, thus rendering the GTPase active (Bustelo25 and Turner and Billadeau26 ).

The Vav subfamily is composed of 3 different genes: Vav1, which is restricted to hematopoietic cells; and Vav2 and Vav3, whose expression pattern is broader.27,28 The 3 of them are involved in lymphocyte ontogeny (Bustelo25 and Turner and Billadeau26 ), and there seems to be some degree of redundancy among them; for example, Vav2 can compensate Vav1 in some contexts, such as B-cell development and function.29 However, redundancy is not absolute; for instance, Vav1-deficient mice have lower numbers of T cells, due to defective pre–T-cell receptor (pre–TCR) signaling, that cannot be replaced by Vav2, which does not seem to participate in T-cell ontogeny.30 Regarding their ability to activate small GTPases, it seems that Vav1 is primarily a GEF for Rac,31 whereas Vav2 and Vav3 would act on Rho.28,32 Their ability to activate Cdc42 is controversial.33

To avoid aberrant signaling to the GTPases, these molecules are finely regulated. In the case of Vav, tyrosine phosphorylation of specific residues induces exposure of the GTPase binding site.34 Thus, Vav appears a likely candidate to mediate signal transduction from CXCR4 to the actin cytoskeleton and therefore control lymphocyte morphology.

In this report, we demonstrate Vav activation by SDF-1α in human primary lymphocytes (peripheral blood leukocytes [PBLs]), as well as inducible association of Vav to CXCR4. Furthermore, the expression of Vav mutants defective in Rac activation impaired cell polarization and migration, further reinforcing the involvement of Vav in CXCR4-mediated signal transduction. On the other hand, overexpression of an oncogenic, constitutively activated form of Vav in human PBLs prevented cell polarization in response to SDF-1α, demonstrating that fine tuning of Vav activation is a requirement for lymphocyte polarization in response to chemokines, thus highlighting the role of Vav in dynamic responses of migratory cells to extracellular chemotactic cues.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Rabbit polyclonal anti-Vav and anti–phospho-Tyr174 Vav (pY174) have been described elsewhere.34 Mouse monoclonal anti–intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM-3) antibody HP2/19 (IgG2a, κ) was previously described.35 Mouse monoclonal anti–human CXCR4 antibody 12G5 (IgG1, κ) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti–mouse CD3 and anti–mouse B220 were from Pharmingen BD (Mountain View, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti–human CXCR4 antibody for immunoprecipitation experiments, anti-FLAG, and human fibronectin were from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO). Polyclonal anti–human CD69 and 90/3, which recognize CD69 and ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins, respectively, have been described elsewhere.35,36 SDF-1α was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). GFP-Vav WT, GFP-Vav (Δ1-186) and untagged Vav (Δ1-186) have been previously described.37 GFP-Vav L213Q and GFP-Vav (Δ1-186) L213Q were obtained from their nonmutated counterparts by site-directed mutagenesis employing QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX), employing the following primers: 5′-GAGGAGAAGTATACAGACACACAGGGCTCCATCCAGCAGCACTTC-3′ and 3′-GAAGTGCTGCTGGATGGAGCCCTGTGTGTCTGTATACTTCTCCTC-5′ (Qiagen Operon GmbH, Cologne, Germany). Introduction of the expected mutation was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing (Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Madrid, Spain). GFP-Rac1 wild type and GFP-G12V Rac1 have been described elsewhere.38 Alexa 647-phalloidin was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

PBL purification

PBLs were purified as described elsewhere.15 Briefly, freshly prepared buffy coats from healthy donors were subjected to gradient centrifugation on Histopaque-1077 (Sigma), followed by 3 rounds of plastic adherence to remove monocytes. Populations were shown to contain less than 2% monocytes as shown by staining with anti-CD14. Approval was obtained from the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Indirect immunofluorescence assays were performed as described.15 Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2 M sucrose and 2 mM MgCl2 for 10 minutes at room temperature and stained for 30 minutes with anti–ICAM-3 or anti-CXCR4 at 37°C followed by incubation with a 1:200 dilution of anti–mouse IgGs coupled to rhodamine red-X (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Cells were then permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 + 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 minutes, followed by incubation with either rabbit anti-Vav or anti–phospho-Tyr174 Vav and staining with highly cross-absorbed anti–rabbit IgGs coupled to Alexa 488. Cells were observed using a Leica DMR photomicroscope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany) with a 100 ×/1.40-0.7 OIL CS objective, coupled to a COHU 4912-5010 CCD Camera (COHU, San Diego, CA). The acquisition software was Leica QFISH V2.1, and images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0. For quantification of cell polarization, at least 300 transfected cells were counted in 4 independent experiments as assessed by ICAM-3 redistribution and formation of 2 well-defined morphological poles.15 Quantitative analysis of cell spreading was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) in at least 50 transfected cells from 3 independent experiments, as described.39

Immunoprecipitation experiments and Western blot

For analysis of Vav phosphorylation, 107 PBLs were stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α for the times indicated, rinsed twice in ice-cold Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), and lysed in buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and COMPLETE cocktail inhibitor tablets (Roche Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany).

For immunoprecipitation, 50 × 106 PBLs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37°C. Cells were then stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α for the times indicated, rinsed twice in ice-cold HBSS, and lysed in buffer containing 1% Brij-96 and complemented as previous protocol. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and protein content in the cell lysates was measured before the pull-down using a protein detection kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). For analysis of Vav phosphorylation, lysates were mixed with 3 × Laemmli buffer and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). For immunoprecipitation, protein extracts were precleared by overnight incubation with 50 μL protein A-agarose (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), centrifuged (15 000g, 1 minute), and immunoprecipitated overnight with the CXCR4 pAb coupled to 50 μL protein A-agarose. The sepharose pellet was washed 5 times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 3 × Laemmli buffer. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% BSA for 30 minutes, and blotted against CXCR4 and Vav (or phosphoTyr174 Vav where indicated), followed by rabbit IgGs coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Chemiluminescence was developed with SuperSignal reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Mice

Vav1-deficient C57/BL10 mice40 were kindly provided by Dr V. Tybulewicz (National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom) and kept in the animal facility of the Centro de Investigación del Cáncer (Salamanca). Control littermates were from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Mice were processed according to institutional guidelines in compliance with international laws and policies. T-cell populations isolated from spleen and lymph nodes were decreased in both the spleens and lymph nodes of Vav1-deficient mice (50% ± 5% vs 22% ± 8%, n = 8 in each case), in agreement with previous reports.40

Migration assay

Migration assays were performed in Boyden-modified chambers (Transwell, Costar, Cambridge, MA) as described elsewhere.18 Quantification of cell migration was performed by counting transfected and nontransfected cells in a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) for 60 seconds. Fluorescence intensity was determined in a FACScalibur flow cytometer. Four cell subsets were defined according to green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression (NULL, LOW, MEDIUM, and HIGH), and the percentage of migrating cells was calculated for each expression interval as previously described.41

F-actin determination assay

Determination of the levels of polymerized actin was performed as described.17 Briefly, lymphocytes from wild-type or Vav1-deficient mice or PBLs from buffy coats were collected as described and resuspended in prewarmed RPMI 1640 medium at 2 × 106/mL, and 100 μL of cells were incubated or not with 10 nM SDF-1α at 37°C for 20 seconds. Then, cells were fixed and permeabilized with 200 μL of CELLwash buffer (Becton Dickinson) for 10 minutes at 4°C and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with 5 μg/mL of Alexa 647-conjugated phalloidin. For Vav+/+ and Vav–/– mice lymphocytes, FL4 (Alexa 647) fluorescence intensity was determined in either CD3+ or B220+ gated cells in a FACScalibur flow cytometer. The relative increase in the level of F-actin was calculated as described in.17

PBL nucleofection

Transfection of human PBLs was performed as follows: 12 × 106 cells were washed twice in ice-cold sterile PBS and resuspended in 100 μL nucleofection T-cell buffer (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). A total amount of 12 μg of the indicated cDNA was added and subjected to the U-14 nucleofection program in an Amaxa Nucleofector I. Cells were resuspended in 4 mL RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS without antibiotics. Expression efficiency was measured 24 hours after nucleofection, and cells were employed in the experiments indicated.

Rac activation assay

GST-PAK-CRIB, which recognizes active Rac and Cdc42, was kindly donated by Dr John Collard (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam) and was prepared as described.42 Pull-down experiments were performed as follows: 5 × 106 of CXCR4-CFP stably expressing HEK-293 cells, kindly provided by Dr M. Mellado (Centro Nacional de Biotecnología, Madrid), were transfected with the calcium phosphate precipitation method with the different constructs of Vav and stimulated for 10 minutes with 10 nM SDF-1α. Following incubation, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS and lysed at 4°C in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane), pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet-P40, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM benzamidine, and COMPLETE cocktail inhibitor tablets (Roche Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The protein content in the cell lysates was measured before the pull-down using a protein detection kit (BioRad, Hercules CA). Equal amounts of protein were incubated with beads coupled GST-PAK-CRIB for 60 minutes at 4°C then washed 4 times in lysis buffer, resuspended in Laemmli buffer, separated in 15% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blot was performed using antibodies against Rac followed by a HRP-conjugated antimouse serum. Detection of chemiluminescence was performed using SuperSignal Pico detection kit from Pierce. Protein loading was controlled using the protein detection kit and by Western blot of one tenth of the sample loaded on a separate blot. For statistical purposes, gels of active and total Rac were subjected to densitometric analysis and normalized with respect to the loading control. Arbitrary units obtained for each condition were then referred to the value of the untreated, GFP-transfected cells to obtain fold induction.

Results

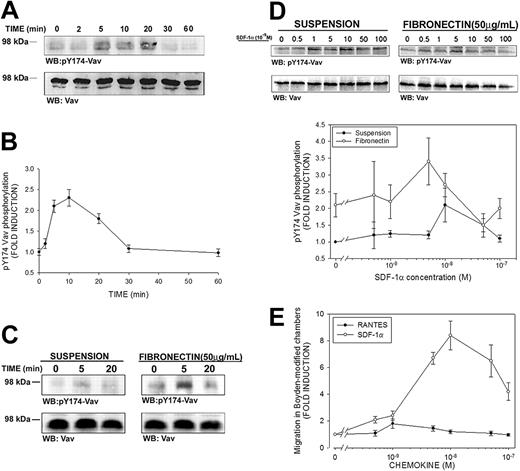

Activation of Vav by SDF-1α in human PBL

Activation of Vav by SDF-1α has been previously suggested in Vav immunoprecipitates of leukemic cell lines by means of the 4G10 antibody, which recognizes phosphorylated tyrosine residues.24 However, it has been shown that only phosphorylation of some tyrosine residues of Vav, such as Tyr174, are bona fide indicators of GEF activation.34 To unequivocally determine whether SDF-1α induced activation of Vav, freshly isolated PBLs from healthy donors were stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α (the dose that induces maximal chemotactic activity in T cells15 ), and immunoblotting analysis was carried out with a polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes Vav phosphorylated at residue Tyr174 (pY174). A time-dependent phosphorylation of Vav was observed in SDF-1α–treated PBLs, which was detectable after 5 minutes of stimulation, reaching a plateau until 20 minutes, and declining thereafter (Figure 1A-B).

SDF-1α induces phosphorylation of Tyr174 of Vav in human PBLs. (A) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for the indicated time points with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed and blotted with a polyclonal antibody against phospho-Tyr174 (pY174) Vav. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted against total Vav. A representative experiment of 4 performed is shown. (B) Kinetics of SDF-1α–induced Vav phosphorylation in human PBLs. Fold induction of pY174 Vav compared to untreated cells and corrected to total Vav is shown. Results represent the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (C) Human PBLs were allowed to spread on 50 μg/mL fibronectin or to remain in suspension and were stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α, lysed and treated as in panel A. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis of 4 performed is shown. (D) Dose-response of SDF-1α–induced Vav phosphorylation in human PBLs. Human PBLs were allowed to spread on 50 μg/mL fibronectin or to remain in suspension and were stimulated with the indicated dose of SDF-1α for 10 minutes, lysed, and treated as in panel A. Quantitative analysis of 4 independent experiments performed is shown. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation. (E) Dose-response of SDF-1α–induced human PBL migration. Human PBLs were allowed to migrate for 3 hours in Boyden-modified chemotaxis chambers in the presence of the indicated doses of SDF-1α (○) or RANTES (regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted; •), used as a control, and migration was quantified by flow cytometry as stated in “Materials and methods.” Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

SDF-1α induces phosphorylation of Tyr174 of Vav in human PBLs. (A) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for the indicated time points with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed and blotted with a polyclonal antibody against phospho-Tyr174 (pY174) Vav. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted against total Vav. A representative experiment of 4 performed is shown. (B) Kinetics of SDF-1α–induced Vav phosphorylation in human PBLs. Fold induction of pY174 Vav compared to untreated cells and corrected to total Vav is shown. Results represent the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (C) Human PBLs were allowed to spread on 50 μg/mL fibronectin or to remain in suspension and were stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α, lysed and treated as in panel A. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis of 4 performed is shown. (D) Dose-response of SDF-1α–induced Vav phosphorylation in human PBLs. Human PBLs were allowed to spread on 50 μg/mL fibronectin or to remain in suspension and were stimulated with the indicated dose of SDF-1α for 10 minutes, lysed, and treated as in panel A. Quantitative analysis of 4 independent experiments performed is shown. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation. (E) Dose-response of SDF-1α–induced human PBL migration. Human PBLs were allowed to migrate for 3 hours in Boyden-modified chemotaxis chambers in the presence of the indicated doses of SDF-1α (○) or RANTES (regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted; •), used as a control, and migration was quantified by flow cytometry as stated in “Materials and methods.” Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

It has been previously reported that adhesion of Jurkat T cells to fibronectin induces Vav phosphorylation, thus decreasing the pool of Vav that can be phosphorylated by other stimuli.43 To ascertain whether lymphocyte adhesion affected the extent to which SDF-1α can phosphorylate Vav, studies were performed similar to that shown in Figure 1A and comparing SDF-1α–stimulated cells either in suspension or adhered to human fibronectin. Interestingly, we found that adhesion by itself induced a 3-fold phosphorylation of Vav, which was further enhanced by addition of SDF-1α up to 6-fold (Figure 1C).

Dose-response experiments showed that the dose of chemoattractant required for maximal phosphorylation of Vav (Figure 1D) is within the range of 5 to 10 × 10–9 M (5-10 nM, 50-100 ng/mL) in adhered cells as well as in the case of suspended cells, which is in the same range of the maximal induction of chemotaxis and cell polarization by this chemokine (Figure 1E and Vicente-Manzanares et al15 ). Together, our data indicate that the Vav phosphorylation induced by integrin ligation is complementary to that induced by chemoattractants, pointing to a role for this molecule in both signaling pathways.

Polarized activation of Vav and interaction with the chemokine receptor CXCR4

The subcellular localization of Vav upon activation with SDF-1α in human PBLs was studied by indirect immunofluorescence experiments on fibronectin. We found that SDF-1α induced cell polarization as previously described,15 and a strong redistribution of the adhesion molecule ICAM-3 to the uropod of migrating cells compared to adhered cells untreated with SDF-1α (Vicente-Manzanares et al15 and Figure 2). Vav adopted a bipolar distribution at both the leading edge (LE) and the cell uropod (U), although no obvious colocalization with ICAM-3 was observed (Figure 2). In addition, Vav was shown to be active at both localizations as demonstrated by staining with the antibody recognizing Tyr174-phosphorylated Vav, which suggested that SDF-1α induced Vav activation and redistribution is important for its function in the control of the morphology of migrating cells.

SDF-1α induces a bipolar distribution of Vav and its activation at the leading edge of human PBLs. Human PBLs were allowed to adhere to 50 μg/mL fibronectin and treated or not with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for ICAM-3 (red) and either pY174 Vav or total Vav (green). Representative fields are shown. LE, leading edge; U, uropod.

SDF-1α induces a bipolar distribution of Vav and its activation at the leading edge of human PBLs. Human PBLs were allowed to adhere to 50 μg/mL fibronectin and treated or not with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for ICAM-3 (red) and either pY174 Vav or total Vav (green). Representative fields are shown. LE, leading edge; U, uropod.

We and others have previously shown that the chemokine CXCR4 is partially clustered at the leading edge of migrating cells during the chemotactic response.9-12 Since Vav was clustered at the leading edge of SDF-1α–responding cells, we studied its possible interaction with CXCR4. Indirect immunofluorescence experiments with either anti-Vav or anti–phospho-Tyr174 Vav suggested their partial colocalization in SDF-1α–stimulated cells (Figure 3A, arrowheads in insets). Remarkably, strong biochemical evidence was provided by CXCR4 immunoprecipitates of SDF-1α–stimulated PBLs, in which we found a clear-cut SDF-1α–dependent interaction of Vav with CXCR4 (Figure 3B). Such biochemical interaction was further confirmed by reciprocal immunoprecipitation, in which we were able to detect CXCR4 in Vav immunoprecipitates (Figure 3C). This fact suggests that CXCR4 probably recruits Vav to the membrane as part of a putative signalosome to transmit signals to the actin cytoskeleton and may regulate the morphology of the cell.

SDF-1α promotes association of Vav to the chemokine receptor CXCR4. (A) Human PBLs were allowed to adhere to 50 μg/mL fibronectin and treated or not with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for CXCR4 (red) and either pY174 Vav or total Vav (green). Yellow spots represent colocalization of CXCR4 and either pY174 Vav or total Vav. Representative fields are shown. LE, leading edge; U, uropod; arrowheads, colocalization. (B) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for the indicated time points with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed, and CXCR4 immunoprecipitated with a specific rabbit polyclonal antibody. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against human CD69 was employed as specificity control. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted against Vav and CXCR4. Fold induction represents the amount of Vav found in CXCR4 immunoprecipitates compared to that in nonstimulated cells. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis of 3 performed is shown. (C) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for 10 minutes with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed, and Vav immunoprecipitated with a specific rabbit polyclonal antibody against Vav. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against human ERM proteins (90/3) was employed as specificity control. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted against CXCR4 and Vav. Fold induction represents the amount of CXCR4 found in Vav immunoprecipitates compared to that in nonstimulated cells. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis are shown.

SDF-1α promotes association of Vav to the chemokine receptor CXCR4. (A) Human PBLs were allowed to adhere to 50 μg/mL fibronectin and treated or not with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for CXCR4 (red) and either pY174 Vav or total Vav (green). Yellow spots represent colocalization of CXCR4 and either pY174 Vav or total Vav. Representative fields are shown. LE, leading edge; U, uropod; arrowheads, colocalization. (B) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for the indicated time points with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed, and CXCR4 immunoprecipitated with a specific rabbit polyclonal antibody. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against human CD69 was employed as specificity control. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted against Vav and CXCR4. Fold induction represents the amount of Vav found in CXCR4 immunoprecipitates compared to that in nonstimulated cells. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis of 3 performed is shown. (C) Human PBLs in suspension were treated for 10 minutes with 10 nM (100 ng/mL) SDF-1α, lysed, and Vav immunoprecipitated with a specific rabbit polyclonal antibody against Vav. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against human ERM proteins (90/3) was employed as specificity control. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted against CXCR4 and Vav. Fold induction represents the amount of CXCR4 found in Vav immunoprecipitates compared to that in nonstimulated cells. A representative experiment and its quantitative analysis are shown.

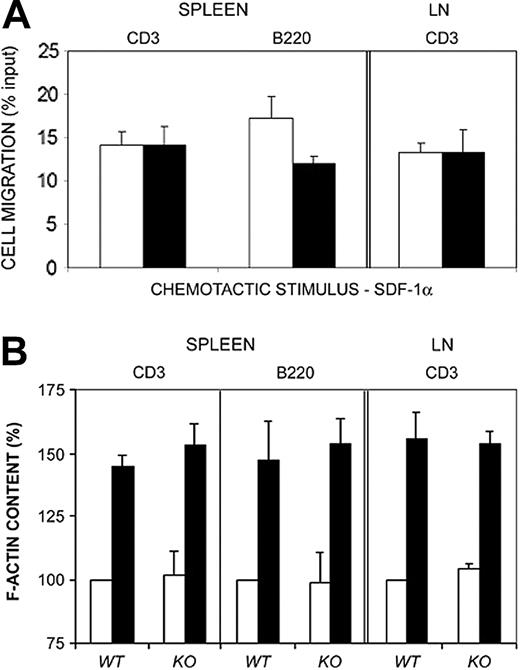

Lymphocytes from Vav1-deficient mice are not defective in responses to SDF-1α

Vav1-deficient mice have proved a useful tool to dissect the role of GEFs in the development of the immune system and its responses.40,44,45 To assess the ability of Vav1-deficient lymphocytes to respond to SDF-1α, we isolated T and B cells from spleens, as well as T cells from lymph nodes of wild-type and Vav1–/– mice and analyzed their response to SDF-1α. Apparently, no major defect was detected on the chemotactic response of Vav1-deficient lymphocytes compared to lymphocytes from control littermates (Figure 4A), in agreement with previous results.46 Furthermore, we found no significant difference on SDF-1α–induced F-actin increase induced by chemokines (Figure 4B), thus suggesting that lymphocytes from Vav1–/– overcome the lack of this molecule by alternative molecular pathways.

Lymphocytes from Vav1-deficient mice do not show defects on SDF-1α–induced cell migration and F-actin increase. (A) Mouse lymphocytes were isolated from spleen or lymph nodes (LN) of wild-type (WT; □) or Vav1–/–-deficient mice (KO; ▪) and allowed to migrate for 3 hours in 3-μm pore diameter Boyden-modified migration chambers in the presence of 10 nM SDF-1α. Transmigrated as well as control cells were stained for CD3 or B220 surface molecules respectively and quantified by flow cytometry. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM of the percentage of transmigrated cells per condition. Wild type, n = 8; Vav1–/–-deficient, n = 8. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (B) Mouse lymphocytes were isolated from spleen or lymph nodes (LN) of wild type or Vav1–/–-deficient mice, stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α for 20 seconds (▪) or not (□), stained for F-actin with Alexa488-conjugated phalloidin, and F-actin content evaluated by flow cytometry. Results correspond to the mean fold induction ± SEM. Wild type, n = 8; Vav1–/–-deficient, n = 8. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Lymphocytes from Vav1-deficient mice do not show defects on SDF-1α–induced cell migration and F-actin increase. (A) Mouse lymphocytes were isolated from spleen or lymph nodes (LN) of wild-type (WT; □) or Vav1–/–-deficient mice (KO; ▪) and allowed to migrate for 3 hours in 3-μm pore diameter Boyden-modified migration chambers in the presence of 10 nM SDF-1α. Transmigrated as well as control cells were stained for CD3 or B220 surface molecules respectively and quantified by flow cytometry. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM of the percentage of transmigrated cells per condition. Wild type, n = 8; Vav1–/–-deficient, n = 8. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (B) Mouse lymphocytes were isolated from spleen or lymph nodes (LN) of wild type or Vav1–/–-deficient mice, stimulated with 10 nM SDF-1α for 20 seconds (▪) or not (□), stained for F-actin with Alexa488-conjugated phalloidin, and F-actin content evaluated by flow cytometry. Results correspond to the mean fold induction ± SEM. Wild type, n = 8; Vav1–/–-deficient, n = 8. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

A dominant negative form of Vav impairs lymphocyte polarization

To investigate the role of Vav in the regulation of lymphoid chemotaxis and cell shape, we obtained different forms of Vav1 fused to GFP (Figure 5A). These constructs exert different effects on Rac activation when overexpressed in HEK-293 cells bearing the SDF-1α receptor CXCR4. We found that Vav wild type induced a 2-fold increase in the levels of GTP-bound Rac, which was more pronounced in the case of the oncogenic Vav (Δ1-186) form (Figure 5B). On the other hand, overexpression of a mutated form of Vav, Vav L213Q, which has been described to impair Rac signaling, virtually abrogated CXCR4-dependent Rac activation (Figure 5B), which postulates a central role for Vav in this signaling cascade, thus confirming the functional effects of Vav on Rac activation.

Oncogenic as well as dominant negative Vav impairs SDF-1α–induced human PBL polarization. (A) Schematics of the constructs employed in these assays. (B) CXCR4-expressing HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated Vav constructs, stimulated for 10 minutes with 10 nM SDF-1α, pull-down experiments were performed with GST-PAK-CRIB construct (which recognizes GTP-bound Rac), and SDS-PAGE–resolved samples were blotted with anti-Rac antibody. A representative experiment of 3 performed is shown. Fold induction has been corrected to the amount of Rac present in the total lysates. (C) Human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav L213Q and allowed to adhere for 30 minutes to 50 μg/mL fibronectin in the presence of 10 nM (100 ng/mL) of SDF-1α for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for ICAM-3 (red). Representative fields are shown. (D) Human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav(Δ1-186) or GFP-Vav human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav(Δ1-186) or GFP-Vav (Δ1-186) L213Q and treated as in panel C. Representative fields are shown. (E) Quantitative analysis of the experiments shown in panels A and B. More than 300 cells per condition have been analyzed in 4 independent experiments. (F) Human PBLs were nucleofected with the indicated Vav constructs, stimulated with 1 (10 ng/mL; ▦) or 10 nM (100 ng/mL; ▪) of SDF-1α for 30 seconds or not (□), fixed, and stained for polymerized F-actin, which was subsequently measured by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. CH, calponin homology; Ac, acidic domain; DH (GEF), Dbl homology guanosine exchange factor; PH, pleckstrin homology; SH, Src homology; ZF, zinc finger.

Oncogenic as well as dominant negative Vav impairs SDF-1α–induced human PBL polarization. (A) Schematics of the constructs employed in these assays. (B) CXCR4-expressing HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated Vav constructs, stimulated for 10 minutes with 10 nM SDF-1α, pull-down experiments were performed with GST-PAK-CRIB construct (which recognizes GTP-bound Rac), and SDS-PAGE–resolved samples were blotted with anti-Rac antibody. A representative experiment of 3 performed is shown. Fold induction has been corrected to the amount of Rac present in the total lysates. (C) Human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav L213Q and allowed to adhere for 30 minutes to 50 μg/mL fibronectin in the presence of 10 nM (100 ng/mL) of SDF-1α for 30 minutes, fixed, and stained for ICAM-3 (red). Representative fields are shown. (D) Human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav(Δ1-186) or GFP-Vav human PBLs were nucleofected with GFP-Vav(Δ1-186) or GFP-Vav (Δ1-186) L213Q and treated as in panel C. Representative fields are shown. (E) Quantitative analysis of the experiments shown in panels A and B. More than 300 cells per condition have been analyzed in 4 independent experiments. (F) Human PBLs were nucleofected with the indicated Vav constructs, stimulated with 1 (10 ng/mL; ▦) or 10 nM (100 ng/mL; ▪) of SDF-1α for 30 seconds or not (□), fixed, and stained for polymerized F-actin, which was subsequently measured by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. CH, calponin homology; Ac, acidic domain; DH (GEF), Dbl homology guanosine exchange factor; PH, pleckstrin homology; SH, Src homology; ZF, zinc finger.

Human PBLs were nucleofected with the constructions indicated (Figure 5A), allowed to adhere to fibronectin in the presence of 10 nM SDF-1α, and stained for the polarization marker ICAM-3. Remarkably, overexpression of GFP-Vav L213Q, which has been shown not to interact with Rac1, thus interrupting Rac1 signaling,37 resulted in abrogated cell polarization monitored by ICAM-3 redistribution to the uropod (Figure 5C,E). However, the distribution of the mutated molecule was very similar to that of wild-type Vav, suggesting its normal recruitment to the membrane (Figure 5C, green). As control, nucleofection of either GFP or GFP-Vav wild type exerted a negligible effect on SDF-1α–induced cell polarization (Figure 5E). These data indicate that Vav L213Q interrupts the signaling from CXCR4 to the actin cytoskeleton that is required to initiate cell polarization, likely by inhibiting further signal transduction to small monomeric GTPases, namely Rac.

Overexpression of oncogenic Vav impairs cell polarization by a mechanism different from Vav L213Q

A mutant of Vav lacking its N-terminus, Vav (Δ1-186), has been shown to possess oncogenic potential and to ectopically activate the small GTPase Rac1 (Figure 5B and Zugaza et al37 ). To assess its effect on PBL polarization induced by SDF-1α, the GFP-Vav (Δ1-186) fusion protein was overexpressed by nucleofection. Vav (Δ1-186) impaired cell polarization induced by SDF-1α (Figure 5D-E). To gain insight on the mechanism by which Vav (Δ1-186) inhibits cell polarization, we performed similar experiments with another mutant Vav (Δ1-186) L213Q, which is almost identical to Vav (Δ1-186) but does not interact with Rac1. This mutant showed no effect on cell polarization induced by SDF-1α (Figure 5D-E), which demonstrates that the inhibitory effect of Vav (Δ1-186) is dependent on downstream activation of Rac1 and concurs with previous results from our group and others showing that overexpression of active Rac1 impairs cell polarization.38 In addition, we found that Vav (Δ1-186) consistently increased the levels of polymerized (F-) actin in human PBLs, whereas SDF-1α–induced actin polymerization was not observed in PBLs expressing Vav L213Q (Figure 5F), which further support that Vav (Δ1-186) and Vav L213Q impair cell polarization by completely different mechanisms.

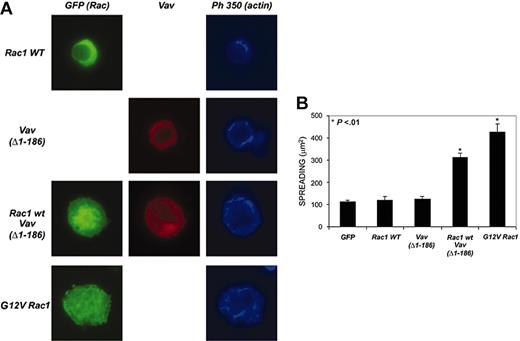

Regarding the effect of Vav on the morphology of the cell, although it has been repeatedly demonstrated that ectopic Rac1 activation by Rac-GEF or activated Rac overexpression induces cell spreading,38 no such spreading was observed in Vav (Δ1-186)–expressing PBLs (Figure 5D). Conversely, overexpression of constitutively activated Rac1 (G12V) in PBL induced cellular spreading and the formation of large actin-based ruffles (Figure 6A), which suggested that perhaps the amount of Rac1 in PBLs was lower than in other cell types, thus constituting the limiting step in cell spreading. To address this issue, we performed co-expression experiments in which PBLs were simultaneously nucleofected with Rac1 wild type and Vav (Δ1-186). We found that Rac1 by itself induced no spreading, which was greatly enhanced in cells co-expressing both molecules (Figure 6A-B), thus suggesting that Rac was actually the limiting molecule for spreading and that overcoming this limitation resulted in enhanced spreading.

Regulation of spreading of PBLs on fibronectin by Vav and Rac. (A) Human PBLs were transfected with the indicated constructions and stained for either Vav (red) or actin (blue). Representative cells are shown. (B) Quantitative analysis of the experiments shown in panel A. More than 50 cells per condition were analyzed with ImageJ for area quantification. Data represent the mean ± SD.

Regulation of spreading of PBLs on fibronectin by Vav and Rac. (A) Human PBLs were transfected with the indicated constructions and stained for either Vav (red) or actin (blue). Representative cells are shown. (B) Quantitative analysis of the experiments shown in panel A. More than 50 cells per condition were analyzed with ImageJ for area quantification. Data represent the mean ± SD.

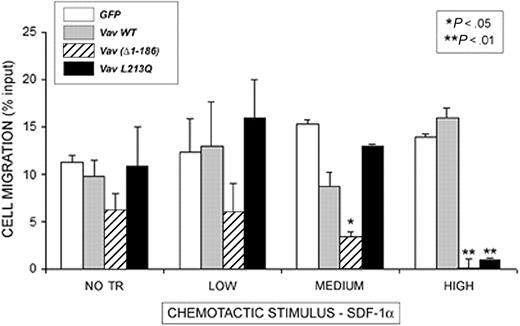

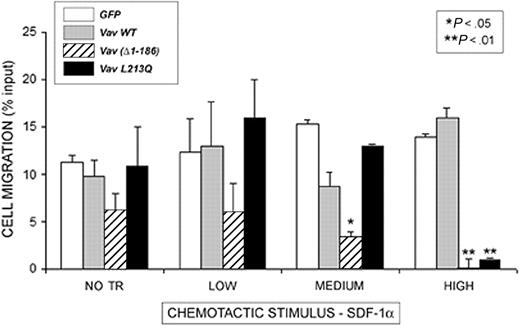

Overexpression of dominant negative or oncogenic Vav impairs chemotaxis

To investigate whether lymphocyte shape changes resulted in impaired cell migration, chemotaxis experiments were performed in Boyden-modified chemotaxis chambers (Figure 7), defining expression gates as previously described.41 We found that none of the constructs exerted any effect on cell migration at low expression. However, Vav (Δ1-186) inhibits chemotaxis to SDF-1α at medium expression levels, which was more evident when high levels of the molecule were expressed (Figure 7). In addition, overexpression of Vav L213Q at high levels resulted in abrogated chemotaxis, which demonstrates a dose-dependent inhibition of chemotaxis by these Vav constructs and further underscores the role of Vav in the chemotactic response.

Oncogenic as well as dominant negative Vav impairs SDF-1α–induced human PBL migration. Human PBLs were nucleofected with the indicated GFP-fusion proteins (□, GFP; ▦, Vav WT; ▦, Vav Δ1-186; and ▪, Vav L213Q) and after 24 hours were allowed to migrate for 3 hours in 3-μm pore diameter Boyden-modified migration chambers in the presence of 10 nM SDF-1α. Cells were gated and analyzed according to their expression of the GFP-fusion protein. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM of the percentage of transmigrated cells per condition in 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate; NO TR, nontransfected.

Oncogenic as well as dominant negative Vav impairs SDF-1α–induced human PBL migration. Human PBLs were nucleofected with the indicated GFP-fusion proteins (□, GFP; ▦, Vav WT; ▦, Vav Δ1-186; and ▪, Vav L213Q) and after 24 hours were allowed to migrate for 3 hours in 3-μm pore diameter Boyden-modified migration chambers in the presence of 10 nM SDF-1α. Cells were gated and analyzed according to their expression of the GFP-fusion protein. Results correspond to the mean ± SEM of the percentage of transmigrated cells per condition in 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate; NO TR, nontransfected.

Discussion

Small GTPases are crucial mediators of cytoskeletal-based shape changes in eukaryotic cells, and their regulation appears as a fundamental step to control complex processes such as cell migration. Directional migration, on the other hand, requires sustained extracellular cues, normally adopting the form of a gradient, soluble or immobilized, which implies 2 fundamental issues: (1) amplification of the signal provided by the gradient; and (2) continuous intracellular cycling of the signaling intermediates to ensure a maintained response.47 It is well known that small GTPases cycle between active and inactive state; such cycling depends on both translocation of the small GTPase to the subcellular location where it exerts its biologic effect and also on interactions with catalytic activators or inhibitors.19 Regulation of the first step is now being unveiled by advances in our understanding of the mechanisms that retain the molecule on the cytoplasm48 or its interaction with second messengers that provide positional information, such as phospholipids or site-restricted phosphorylation.49 Such processes are usually coordinated, that is, GEFs can be phosphorylated at specific cellular locations, thus rendering the GTPase active within that location. In agreement with this notion, this work shows that the chemokine SDF-1α induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the GEF Vav at Tyr174, a residue that has been consistently shown to regulate Vav activity; as such phosphorylation destroys the intramolecular interaction of the N-terminus of Vav with its C-terminus, which allows the Rac binding site to remain hidden and inactive. This is a more consistent indicator of Vav activation than those experiments in which Vav is immunoprecipitated and total phosphotyrosine revealed, as Vav can be phosphorylated in other tyrosine residues, whose implication in Vav activation is not so clear, even leading to its down-modulation.34 Phosphorylation of Vav at this residue is likely to be dependent of ZAP-70, since this kinase has been described to activate Vav in leukemic cells.24 Vav phosphorylation occurs in response to different extracellular stimuli, that is, growth factors, adhesion, etc. For cell migration to occur, 2 signals are required, which are cell adhesion and a promigratory stimulus. It has been previously shown that adhesion of Jurkat T cells to fibronectin induces Vav phosphorylation.43 Consistent with this, we found fibronectin-induced Tyr174 Vav phosphorylation in human PBLs. In addition, SDF-1α induced further phosphorylation of Vav at Tyr174, which suggests that adhesion per se is not able to induce maximal activation of Vav during cell migration, which is achieved by the combination of adhesive and chemoattractant stimuli.

Furthermore, we found that phosphorylated Vav is restricted to the leading edge of migrating cells and to the trailing edge or uropod. Activated Vav at the leading edge probably regulates its formation and perpetuation inducing the local activation of Rac and thus actin polymerization through a WAVE/Scar-Arp2/3–dependent mechanism50,51 and/or relaxation of myosin-dependent tension by Pak-dependent phosphorylation of myosin-II heavy chain,52 but the role of Vav activation at the uropod is currently unknown. However, Vav activation at the uropod may be a consequence of its interaction with the Syk kinase, which is an upstream regulator of Vav.53 In this regard, Syk kinase is recruited to the uropod, where it associates to an ITAM-like motif within ERM adaptor proteins.54 Thus, it is likely that Vav activation at the uropod may occur at adhesion molecule–dependent signalosomes including both ERMs and Syk. However, we have been unable to detect Vav in immunoprecipitates of adhesion molecules clustered at the uropod of the cell (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that Vav presence in the uropod of the cell is associated with the formation of actin cables at the trailing edge of the cell, which are involved in adhesion turnover and retraction. On the other pole of the cell, SDF-1α induces colocalization and biochemical association of Vav with the chemotactic receptor CXCR4. We have previously shown that this also occurs for type IA PI 3-kinase,15 thus we can speculate that, following SDF-1α stimulation, a signalosome is formed under CXCR4, which recruits signaling intermediates that transmit the chemotactic signal to the actin cytoskeleton. Vav would be included in such a signalosome, but it is unlikely that it directly interacts with CXCR4, since no Pro-rich domain (that might interact with the SH3 domain of Vav) or consensus phosphorylated Tyr (for interaction with the SH2 domain) have been described in the cytoplasmic tail of CXCR4.

Contrary to what occurs in the GRK-dependent complex, actin polymerization–inducing complexes are mainly dependent on heterotrimeric inhibitory G (Gi) proteins, since pertussis toxin–treated cells are still able to undergo CXCR4 internalization but not actin polymerization.55,56 It is interesting to note that Vav still remains biochemically bound to CXCR4 when Vav phosphorylation is declining (20 minutes), which suggests the existence of in situ signal limitation processes that switch off Vav prior to its dissociation from the receptor. In this regard, both CXCR4 and Vav have been shown to interact with different membrane and cytoplasmic phosphatases, which may play a role in signal turn-off.57,58

The role of Vav in the propagation of CXCR4 signaling to the cytoskeleton is highlighted by overexpression of a GEF-deficient form of Vav, in which the critical residue for interaction with Rac has been point-mutated. This form is still recruited to the membrane but blocks the polarizing response to SDF-1α as well as PBL migration to the chemokine.

In recent years, cells from Vav-deficient mice have proved useful tools to explore the immunobiology of these molecules. Having access to Vav1-deficient mice, we performed ex vivo migration and actin polymerization experiments with T and B cells from such mice. These mice showed reduced numbers of T cells, as previously described,40 but were devoid of other obvious defects. Cell polarization experiments proved extremely difficult to perform, probably due to the lack of an appropriate integrin-dependent substrate, although monocyte spreading, which occurs spontaneously and in the absence of integrin-dependent interactions, was unaffected in Vav1-deficient cells (data not shown). A range from 0.1 nM to 1 μM SDF-1α was assayed with no significant differences in lymphocyte migration or F-actin increase responses to SDF-1α. It is likely that these lymphocytes have overcome the Vav1 defect, probably employing Vav2 or Vav3 instead for CXCR4-dependent responses. Our data with dominant negative forms of Vav suggest that this mutant binds to the interaction site of Vav in the putative CXCR4 signalosome, thus blocking further interaction of other Vav members, which are given free access in the case of the Vav1-deficient lymphocytes.

A previous report clearly showed that overexpression of an activated mutant of Rac1 blocked leukemic cell polarization due to increased and omnidirectional cell spreading.38 Consistent with this, overexpression of Vav (Δ1-186) resulted in abrogated cell polarization, but rather unexpectedly, it did not induce cell spreading, whereas the activated mutant of Rac1, V12Rac, induced a modest, round-shaped cell spreading. However, the fact that V12 Rac was actually able to induce spreading together with the fact that PBLs contained comparable amounts of actin to leukemic cells (data not shown) made unlikely that the amount of actin within PBLs was responsible for the spreading defect. To determine whether other components could be limiting this response, we overexpressed wild-type Rac together with Vav (Δ1-186), finding that this combination enhanced PBL spreading, allowing us to postulate that the spreading defect was caused by a limiting amount of Rac in PBLs.

Together, our data demonstrate the key role of Vav proteins in the chemotactic response and provide a functional link between chemokine triggering and lymphocyte polarization and migration in response to extracellular cues.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 23, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2925.

Supported by grant BMC02-00563 from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología; grant 2002 for Basic Research from the Juan March Foundation; grant 36289/02 from FIPSE (Fundación para la Investigación y Prevención del SIDA en España) (F.S.-M.); grant LSHG-CT-2003-502935-MAIN Network of Excellence from European Union; and grant SAF2003-00028 from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología.

A.C.-A. and N.B.M.-C. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We acknowledge Drs Isabel Olazabal and Manuel Gómez for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr Mario Mellado (Centro Nacional de Biotecnología, Madrid) for his kind donation of CXCR-4-293-HEK cells and technical advice. I.O. and M.G. are scientists of the Ramón y Cajal Program (Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain).