Abstract

Mutations in the SH2D1A gene have been described in most patients with the clinical syndrome of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP). The diagnosis of XLP is still difficult given its clinical heterogeneity and the lack of a readily available rapid diagnostic laboratory test, particularly in patients without a family history of XLP. XLP should always be a consideration in males with Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH). Four-color flow cytometric analysis was used to establish normal patterns of SH2D1A protein expression in lymphocyte subsets for healthy subjects. Three of 4 patients with XLP, as confirmed by the detection of mutations in the SH2D1A gene, had minimal intracellular SH2D1A protein in all cytotoxic cell types. The remaining patient lacked intracellular SH2D1A protein in CD56+ natural killer (NK) and T lymphocytes and had an abnormal bimodal pattern in CD8+ T cells. Carriers of SH2D1A mutations had decreased SH2D1A protein staining patterns compared with healthy controls. Eleven males with clinical syndromes consistent with XLP, predominantly EBV-HLH, had patterns of SH2D1A protein expression similar to those of healthy controls. Four-color flow cytometry provides diagnostic information that may speed the identification of this fatal disease, differentiating it from other causes of EBV-HLH.

Introduction

X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP; Mendelian Inheritance in Man [MIM] 308240) is a congenital immunodeficiency estimated to affect approximately 1 in 1 × 106 males.1 XLP has been characterized by exquisite vulnerability to fatal complications of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. An estimated 90% of affected males present with fulminant infectious mononucleosis and hemophagocytosis, which is clinicopathologically identical to EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH).2 More than 80% of patients with EBV-HLH can be cured with chemotherapy.3 In contrast, at present XLP is only curable by transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells.4 Therefore, it is important to differentiate XLP from EBV-HLH.

In 1998, 3 groups of investigators reported the identification of a gene (SH2D1A, DSHP, or SAP) at Xq25 that is absent or mutated in patients with XLP.5-7 The gene spans 40 kb of genomic sequence and contains 4 exons. The human SH2D1A gene gives rise to a transcript of 2.5 kb expressed in T lymphocytes, thymus, fetal liver, colon, and spleen, which encodes a protein of 128 amino acids. The SH2D1A protein is composed almost entirely of an SH2 domain and interacts with members of the SLAM family of immune cell–specific receptors required for carefully controlled T cell and natural killer (NK) cell responses during EBV infection. Germline mutations in the SH2D1A gene have been identified in approximately 55% to 60% of patients manifesting one of the XLP phenotypes.8 Another study showed that SH2D1A protein expression is undetectable in patients with XLP confirmed using immunoblot.9 It has been suggested that patients with XLP without SH2D1A mutations in the coding region of the gene might harbor mutations in the intronic sequences or in the regulatory regions of the SH2D1A gene. Another study has shown partially defective transcription of SH2D1A in a patient with XLP who has a single nucleotide change in the exon 2 splice-acceptor site. Although this patient still produces 10% of the wild-type SH2D1A mRNA, he presented with typical XLP symptoms.7 It has also been reported that some of the missense mutations of the SH2D1A gene result in markedly decreased protein half-life in a transient expression system.10 Such observations suggest that analyzing SH2D1A protein expression in conjunction with genetic sequencing is important for a definitive diagnosis of XLP.

In this report, we describe an assay using 4-color flow cytometry to detect intracellular SH2D1A protein expression to facilitate the rapid diagnosis of patients with XLP and potentially related disorders. The objectives of our work were to validate the rapid technique for the measurement of SH2D1A protein levels in subsets of cytotoxic human lymphocytes, to establish normal patterns of SH2D1A protein expression in control subjects, and to study the pattern of SH2D1A protein expression in patients with XLP and in their family members.

Patients, materials, and methods

Control samples

To establish normal ranges of intracellular SH2D1A expression, heparinized peripheral blood was obtained from 20 healthy volunteers (10 men, 10 women). All samples were held at room temperature and were processed within 24 hours of collection. These conditions were studied during the process of assay development and were found to be optimal for obtaining reproducible results in healthy persons.

Patient and family member samples

Samples submitted to the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Hematology/Oncology Diagnostic Laboratory for testing to rule out XLP were screened for SH2D1A protein expression when requested by the referring physician. Written informed consent had been provided by the families, in compliance with an Institutional Review Board (IRB)–approved research protocol. A clinical diagnosis of XLP was either confirmed or dismissed in each case by the referring institution. All samples were held at room temperature and were processed within 24 hours of collection. All samples were tested for SH2D1A mutations.

Detection of intracellular SH2D1A protein by flow cytometry

One hundred microliters of whole blood per test tube was first surface stained with the antibodies CD3–antigen-presenting cell (CD3-APC), CD8–peridin chlorophyll protein (CD8-PerCP), and CD56-phycoerythrin (CD56-PE) for 15 minutes at room temperature. IntraPrep reagent (Immunotech, Marseille, France) was used for fixation and permeabilization according to the manufacturer's instruction. Then the cells were incubated with unconjugated rat anti-SH2D1A monoclonal antibody KST-3, which recognizes the C-terminal of the human SH2D1A protein,11 or with purified rat immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) for 20 minutes at room temperature and were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled mouse antirat IgG1 antibody for 20 minutes at room temperature. After washing, cells were resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C before analysis by flow cytometry. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The following gates were used to distinguish the 3 populations of interest: CD8+ T cells were defined as CD3+CD8+CD56–; NK cells were defined as CD3–CD56+; and CD56+ T cells were defined as CD3+CD56+. All populations were also restricted to a lymphocyte gate based on forward versus side scatter. The SH2D1A-positive region was set using an isotype-matched negative control, and the percentage positive for each region was reported. (All antibodies except KST-3 used in this experiment were purchased from BD Biosciences.)

Detection of SH2D1A mutations

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood or buccal swabs according to standard protocols. The coding region and the exon-intron boundaries of the SH2D1A gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primer pairs flanking each of the 4 SH2D1A exons.1 Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from herpesvirus saimiri (HSV)–transformed T cell lines established from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of the patients and healthy volunteers, as described previously.12 cDNA was generated using reverse transcriptase (RT) and was followed by PCR with primer pairs flanking the coding region of SH2D1A gene.13 Direct sequencing of the PCR products was performed using the ABI 3730XL sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the same primer pairs used for PCR amplification. Mutational data are reported based on the standard nomenclature recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics that nucleotide +1 is the A of the ATG translation initiation codon.

Immunoblot analysis

HVS-transformed T cell lines derived from 2 patients and 2 healthy volunteers were used for this experiment. The cells were washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pelleted, and lysed in M-PER protein extraction reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). For immunoprecipitations, the lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:300 dilution of the polyclonal rabbit antiserum to human SH2D1A.14 Immune complexes were collected by adding protein A–agarose (Invitrogen). Proteins from the equivalent of 5 × 106 cells were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked overnight with 5% nonfat milk powder in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and was incubated with the same polyclonal anti-SH2D1A antiserum. The membrane was washed with TBS-T and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit antibody before chemiluminescence detection using SuperSignal West Pico substrate (Pierce). To verify the integrity of the lysates, the membrane was then incubated with a goat antiactin antibody followed by a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated mouse antigoat antibody and was detected as described. (All antibodies except anti-SH2D1A antiserum used in this experiment were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)

Results

Intracellular SH2D1A protein expression in normal control samples

Normal proportions of SH2D1A-expressing cells were analyzed in total lymphocytes, T cells, CD8– T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ T cells, and NK cells in whole blood from 10 healthy men and 10 healthy women. Normal ranges were calculated as mean ± 2 SD. The highest proportions of SH2D1A-expressing cells, 73% ± 28%, were found in CD56+ T cells. The lowest were in CD8– T cells (5% ± 4%). The proportions of SH2D1A-positive CD8+ T cells and NK cells were 65% ± 22% and 48% ± 22%, respectively (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were observed between male and female controls in any of the lymphocyte subsets.

Intracellular SH2D1A expression and genomic mutational analysis of the patients with XLP

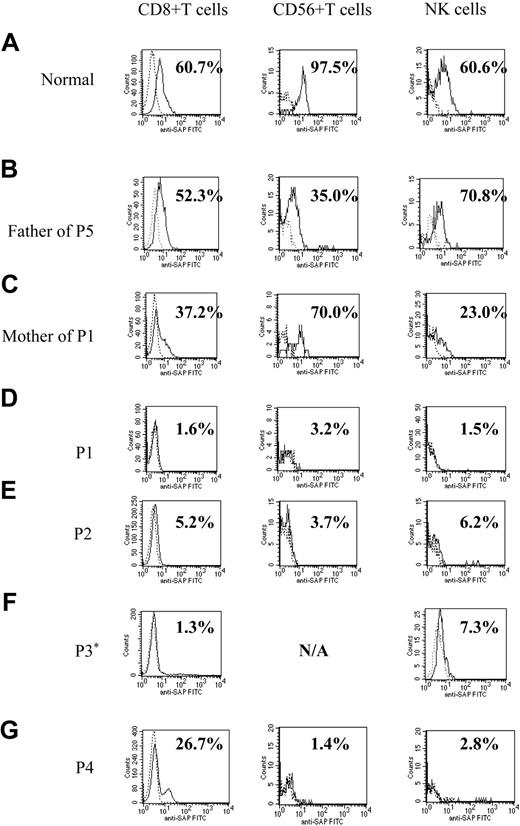

Figure 1 shows representative histograms from a healthy control, 4 patients with XLP, and family members of 2 patients (father of patient 5 and mother of patient 1). SH2D1A protein expression was within the normal ranges for all 3 lymphocyte subpopulations from the healthy control and the father of patient 5. The histogram of the mother of patient 1 (XLP carrier) shows decreased proportions of SH2D1A-positive CD8+ T and NK cells. Flow cytometry of the patients with XLP showed markedly decreased intracellular SH2D1A expression (less than 10%) in all lymphocyte subpopulations except for that seen in CD8+ T cells from patient 4 (Figure 1). Patient 4 was found to have a previously unidentified SH2D1A mutation. The histogram of CD8+ T cells showed a large negative peak and an unusually small positive peak, representing 26.7% positive cells.

Histograms demonstrating intracellular SH2D1A expression in patients with XLP. Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular SH2D1A expression. (A) Representative healthy control. (B) Normal expression, the father of patient 5 (P5). (C) XLP carrier, the mother of patient 1. P1 to P4 (D-G) are patients with confirmed mutations of the SH2D1A gene. Lymphocytes are gated and stained with anti-SH2D1A antibody (continuous lines) or irrelevant rat IgG (dashed lines) and additional FITC-labeled, antirat IgG antibody. *SH2D1A expression in CD56+ T cells of patient 3 was not measured (N/A) because the number of CD56+ T cells in his sample was too low.

Histograms demonstrating intracellular SH2D1A expression in patients with XLP. Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular SH2D1A expression. (A) Representative healthy control. (B) Normal expression, the father of patient 5 (P5). (C) XLP carrier, the mother of patient 1. P1 to P4 (D-G) are patients with confirmed mutations of the SH2D1A gene. Lymphocytes are gated and stained with anti-SH2D1A antibody (continuous lines) or irrelevant rat IgG (dashed lines) and additional FITC-labeled, antirat IgG antibody. *SH2D1A expression in CD56+ T cells of patient 3 was not measured (N/A) because the number of CD56+ T cells in his sample was too low.

Table 2 shows data for the 4 patients with XLP with mutations of SH2D1A. Patients ranged from 5 months to 23 years of age. Patient 2 had a missense mutation (102C>A) introducing a Ser34Arg amino acid transition. The other 3 patients had 3 different single nucleotide changes in the exon-intron boundaries, which were predicted to prevent normal splicing of the SH2D1A mRNA. Patient 1 had 138(–2) a>c, a single nucleotide change at the 5′-splice acceptor site of exon 2. Patient 3 had 138(–2) a>gatthe same position as patient 1. Patient 4 had 201(+3) a>g at the 3′-splice acceptor site of exon 2. An additional patient and his asymptomatic identical twin were also found to have markedly reduced SH2D1A protein expression by flow cytometry in the same range as the patients shown in Figure 1. He was found to have a novel mutation in an intron-exon boundary of the SH2D1A gene (N. Zavazava et al, manuscript in preparation).

Intracellular SH2D1A expression and genomic mutation analysis in family members

Table 3 shows flow cytometric data for 4 family members of patients with XLP (patients 1 and 5). Patient 5 was a 4-year-old boy with a family history of XLP. Retrospective mutation analysis showed a nonsense mutation (191G>A), introducing Trp64Stop transition. The diagnosis was XLP, and he underwent bone marrow transplantation before symptoms appeared. No pretransplantation sample was available for intracellular SH2D1A staining. Family members shared the same SH2D1A gene mutations as the patients. All carriers showed decreased expression compared with the normal range, except for that seen in CD56+ T cells from the mother of patient 1, but higher levels than patients with mutations of SH2D1A. An unaffected adult male (father of patient 5), studied as part of XLP family analysis, was identified with the intron 3 variant 347(–30)del5 nucleotide change, previously reported in a patient with XLP,15 but showed normal SH2D1A expression (Figure 1).

Intracellular SH2D1A expression in patients with clinical XLP without mutations in the SH2D1A gene

Eleven male patients exhibiting symptoms consistent with XLP, in whom no mutations in SH2D1A were found, showed varied patterns of SH2D1A expression (Table 4). Seven of them had normal SH2D1A expression, including 1 patient with a convincing X-linked family history. The other 4 patients showed slightly decreased SH2D1A expression that was easily distinguishable from patterns of patients with SH2D1A mutations. Intracellular perforin expression and PRF1 mutation analysis were also investigated, as described previously.16

RT-PCR and mutation analysis in the SH2D1A mRNA from patients with genomic mutations

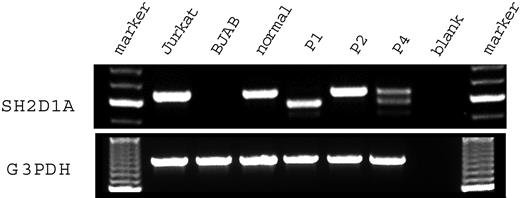

Figure 2 shows the results of a reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay of SH2D1A expression in the HSV-transformed T cell lines from 3 patients with genomic mutations of SH2D1A and control samples. Jurkat, a T-lymphoid cell line, and BJAB, a B-lymphoid cell line, were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Quality of the RT-PCR was confirmed by amplification of the glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) mRNA. Jurkat showed an amplified fragment of 632 base pair (bp) using primers for SH2D1A. No amplification was shown from the mRNA of BJAB. Patient 1 had a truncated amplified fragment (568 bp). Patient 2 had a fragment the same size as that of the healthy control. Patient 4 had 1 fragment of normal size and another shorter fragment (513 bp). Material for patient 3 was unavailable for RT-PCR.

SH2D1A mRNA expression in T cell lines derived from patients with XLP. RNA was extracted from the transformed T cell lines derived from the patients with XLP and a healthy control. Then RT-PCR was performed with primer pairs flanking the coding region of the SH2D1A gene. Marker indicates molecular marker; Jurkat, T-lymphoid cell line, positive control; BJAB, B-lymphoid cell line, negative control; normal, healthy control; P1, patient 1; P2, patient 2; P4, patient 4; blank, amplified without DNA.

SH2D1A mRNA expression in T cell lines derived from patients with XLP. RNA was extracted from the transformed T cell lines derived from the patients with XLP and a healthy control. Then RT-PCR was performed with primer pairs flanking the coding region of the SH2D1A gene. Marker indicates molecular marker; Jurkat, T-lymphoid cell line, positive control; BJAB, B-lymphoid cell line, negative control; normal, healthy control; P1, patient 1; P2, patient 2; P4, patient 4; blank, amplified without DNA.

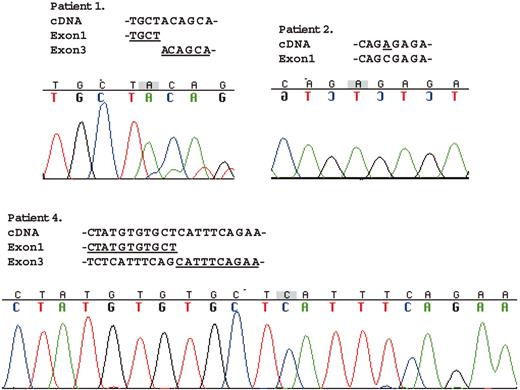

Figure 3 shows the mutation analysis data of the amplified fragments by RT-PCR for SH2D1A. The mRNA from patient 1 lacked exon 2 totally, which causes a different amino acid sequence after the end of exon 1 from amino acid position 47 to 58 (QHLGYIKDISGK) and an early termination at 59. The data for patient 2 showed the same 102C>A missense mutation as in the genomic mutational analysis, which causes 1 amino acid alteration from serine to arginine at position 34. Two fragments of different size were amplified in the cell line from patient 4. The longer fragment had no mutations (data not shown). The shorter fragment lacked exon 2 entirely as well as the first 55 nucleotides of exon 3, which caused a different amino acid sequence after the end of exon 1 from amino acid position 47 to 62 (ISEARSRHCNTSAVSS) and an early termination at amino acid position 63.

Mutational analysis ofSH2D1AmRNA from the patients with XLP. Direct sequencing of the RT-PCR products was performed with the same primer pairs used for PCR amplification. The amplified fragment from patient 1 totally lacked exon 2. Data for patient 2 showed the same 102C>A missense mutation as in the genomic mutational analysis. Of the 2 different size-amplified fragments from patient 4, the longer fragment had no mutations (data not shown). The shorter fragment lacked exon 2 entirely and the first 55 nucleotides of exon 3.

Mutational analysis ofSH2D1AmRNA from the patients with XLP. Direct sequencing of the RT-PCR products was performed with the same primer pairs used for PCR amplification. The amplified fragment from patient 1 totally lacked exon 2. Data for patient 2 showed the same 102C>A missense mutation as in the genomic mutational analysis. Of the 2 different size-amplified fragments from patient 4, the longer fragment had no mutations (data not shown). The shorter fragment lacked exon 2 entirely and the first 55 nucleotides of exon 3.

Immunoblot analysis of the SH2D1A protein from the patients with XLP

No SH2D1A protein was detected by immunoblot in T cell lines from patients 1 and 2 (data not shown). Materials for patients 3 and 4 were not available for immunoblot analysis.

Discussion

XLP is a rare inherited immunodeficiency in which severe immunodysregulatory phenomena occur typically after exposure to EBV. Most patients with XLP die by age 40, and more than 70% of patients die before age 10.17 The gene defective in XLP has been identified at Xq25 and has been designated SH2D1A. Mutation analysis of the gene is currently required for a definitive diagnosis of XLP. Germline mutations in the gene, however, have only been identified in approximately 55% to 60% of patients manifesting 1 of the XLP phenotypes.8 Previous studies have shown that SH2D1A protein expression is undetectable in patients with confirmed XLP.9,18 The diagnosis of XLP is difficult given its clinical heterogeneity and the lack of a rapid diagnostic laboratory test, particularly with males manifesting a phenotype consistent with XLP but without a family history. Recent improvement of the prognosis of XLP by transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells makes early diagnosis more important.

Our results suggest that analyzing SH2D1A protein expression is useful for a definitive diagnosis of XLP. Immunoblot analysis requires a larger volume of blood, lacks the sensitivity of lymphocyte subset analysis, and takes longer to perform. When a differential diagnosis of XLP is needed, especially in a young patient critically ill with active EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, a rapid diagnostic test is desirable. The technique we describe here has proven to be rapid, reproducible, and informative. We have shown that the lymphocytes of patients with XLP express significantly decreased SH2D1A protein compared with those of healthy subjects. Only a few hundred microliters of peripheral blood and a few hours are needed for the procedure.

More than 30 nucleotide mutations in the SH2D1A gene have been reported.8 Few studies have correlated nucleotide mutations and protein expression in the relevant lymphocyte subsets. In our studies, we found 3 different nucleotide changes in noncoding regions of SH2D1A (138(–2)a>c, 138(–2)a>g, and 201(+3)a>g). All these nucleotide changes were found in splice acceptor sites. Mutation analysis revealed that the 2 patients we tested had nucleotide deletions in the coding regions of the mRNA. The detection of SH2D1A protein from these patients by flow cytometry showed significantly decreased SH2D1A expression. These results confirmed the previous study for the shorter half-life of the mutated SH2D1A proteins using immunoblot.10

Studies of samples from patient 4 revealed that 1 nucleotide change in the splice acceptor site caused 2 differently spliced transcripts (normal and truncated) and 2 different peaks of protein expression by flow cytometry. He had significantly decreased SH2D1A expression in CD56+ T cells and NK cells but a small positive peak in CD8+ T cells. Similar patterns of bimodal intracellular protein expressions in T cells by flow cytometry have been reported in patients with revertant mosaicism in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.19 Spontaneous reversion of genetic defects in T cells are being described in an increasing number of primary immunodeficiencies.19-21 Although revertant mosaicism has not yet been reported in patients with XLP, it is possible that the normal genetic sequence was restored in some of the CD8+ T cells from patient 4. Alternatively, certain mutations may result in differential lineage-specific regulation of SH2D1A expression, about which little is known. Importantly, after flow cytometry, studies confirmed the diagnosis of XLP in patient 4. XLP had not been diagnosed before the flow cytometric analysis because the mutation was not thought to be a disease-causing mutation. He was referred for bone marrow transplantation.

We also studied a healthy male who was incidentally found to have 347(–30)del5, a 5-bp deletion in a noncoding region of SH2D1A that was previously reported to cause disease,15 because it was identified in a male with a clinical diagnosis of XLP. It is possible that this mutation is disease causing and that the individual in this study (father of patient 5) has remained presymptomatic for more than 30 years. However, this nucleotide change is located 30 bp upstream of the intron-exon boundary and may not cause any effects on mRNA splicing. The sister of patient 5 has 2 nucleotide changes in the SH2D1A gene, 191G>A from her mother and 347(–30)del5 from her father. She had decreased SH2D1A expression by flow cytometry compared with healthy controls. Her mother shared the 191G>A mutation and had similar decreased protein expression. These data suggest that the 347(–30)del5 nucleotide change does not have significant impact on SH2D1A protein expression. None of the family members had symptoms consistent with XLP. Thus, on the basis of lack of clinical phenotype and demonstrated normal SH2D1A expression, we suggest that 347(–30)del5 is a genetic variant, not a pathologic mutant. We propose that correlating SH2D1A expression with nucleotide changes in SH2D1A may help to exclude those that are not clinically significant.

According to a previous study, T and NK cells, but not B cells or monocytes, were responsible for the detection of SH2D1A in normal peripheral blood using immunoblots.22 No previous studies, however, have reported the extent of SH2D1A expression in T and NK cell subsets. Our analyses clearly show that the proportions of SH2D1A-positive cells in cytotoxic lymphocyte subsets, including CD8+ T cells, CD56+ T cells, and NK cells, are significant but not universal (65%, 73%, and 48%, respectively). It has previously been concluded that helper CD4+ T cells express SH2D1A.17 These conclusions were based on observations in leukemic cell lines or long-term culture of lymphocytes stimulated in vitro.14 In our experiments, using freshly obtained peripheral blood lymphocytes, helper T cells, defined as CD3+ and CD8– lymphocytes, express little SH2D1A protein. This observation suggests that the expression of SH2D1A is regulated differently in T cell subsets and NK cytotoxic lymphocytes in vivo.

Recently, Hugle et al23 reported that they detected SH2D1A protein in a patient with XLP by immunoblot using a different antibody. The patient had a missense mutation (79G>A), introducing G27S single amino acid alteration. Although we have not yet analyzed any samples with the same G27S mutation, it is possible that the mutated SH2D1A protein could be detected by our flow cytometric method. Further studies are needed to expose such potential intrinsic limitations of this flow cytometric method.

In conclusion, the patient study suggests that a flow cytometric assay examining different lymphocyte populations constitutes a rapid and sensitive approach for the diagnosis of XLP and for the screening of potential carriers of XLP. We recommend that in addition to genetic analysis, all patients with clinical criteria consistent with XLP be studied for intracellular SH2D1A staining. In families in whom SH2D1A deficiency has been documented and the SH2D1A-staining pattern in an affected member has been determined, this technique can be reliably applied to screen asymptomatic male newborns for XLP.

Furthermore, some patients with HLH without SH2D1A mutations showed slightly decreased intracellular SH2D1A staining patterns. It is possible that the expression of SH2D1A protein can be functionally suppressed in these patients, as has been reported in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.24 Additional studies are needed to determine the relationship between the function of SH2D1A and life-threatening hemophagocytic syndromes.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 4, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3651.

Supported by a Pediatric Oncology Research Fellowship from the Children's Cancer Association of Japan (Y.T.), grant 6-FY01-64 from the March of Dimes (J.S.), and grants from the Histiocytosis Associations of America and Canada.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank all the participating families and physicians for their generous cooperation in this study, and we thank Sue Vergamini and Daniel Marmer for excellent technical support.